Outside observers may have the impression that women are adequately represented in the United States. From the extreme left to the extreme right, female political leaders appear to be front and centre in US politics. Hillary Clinton and Sarah Palin are household names all over the world. More sophisticated political observers will also know prominent congressional leaders such as Nancy Pelosi or Michele Bachmann. In reality, however, the United States has a large issue when it comes to female representation. In fact, it consistently ranks lower than almost every other Western democracy in this category (Rosen Reference Rosen2011). Our own data show that, between 1972 and 2012, women won less than 10 per cent of all elections contested within the US House of Representatives. If race and gender are taken into account together, then the representation issues of the United States are fully exposed, with black women winning only around 1.5 per cent of all races contested in the same period of time.

This article sheds some light upon the underrepresentation of women in the US Congress. We argue that this underrepresentation is a consequence of a rigid and static political system that grants considerable advantages to incumbent candidates. This incumbency advantage constitutes a real political glass ceiling (cf. Palmer and Simon Reference Palmer and Simon2001) that systematically prevents women from being adequately represented. At the same time, however, we also note that once women enter the US Congress, they do enjoy the same benefits as their male colleagues. In brief, our final assessment is that there is no overt or covert discrimination against women within the US Congress when it comes to their career length and service. Instead, the system provides a clear advantage to whomever is in power, and they currently happen to be male. We reach this conclusion by analysing whether the careers of female Members of Congress (MCs) are any different from those of male MCs in the US House of Representatives. We carefully assess both length of service and importance of the careers of males and females, utilizing data on congressional tenure and committee assignments for all MCs elected between 1972 and 2012. With the help of descriptive and inferential statistics, we find that the length of male and female House tenures and the importance of careers are alike for the two genders, with the latter possibly even slightly favouring women.

UNDERSTANDING FEMALE REPRESENTATION IN THE US CONGRESS

In comparison to other Western democracies – and arguably to most countries in the world – the United States features a mix of most of the factors that the comparative literature identifies as disadvantageous in terms of female representation (Tremblay Reference Tremblay2012). From a cultural point of view, the level of religious activity, coupled with the non-existence of real leftist political movements and parties, is detrimental to the representation of women (cf. Inglehart and Norris 2003; Mateo Diaz Reference Mateo Diaz2005; Paxton and Kunovich Reference Paxton and Kunovich2003). Socioeconomically, the gender gap in high-ranking jobs, the almost total lack of welfare provisions designed to keep women in the workforce and the high levels of income inequality generally registered throughout the country are all factors known to contribute to low levels of female representation (cf. Darcy et al. Reference Darcy, Welch and Clark1994; Reynolds Reference Reynolds1999; Rosenbluth et al. Reference Rosenbluth, Salmond and Thies2006). Even most of the institutional makeup of the United States, from its single-member electoral districts to the complete lack of gender quotas at all levels of political representation, contribute to make the US a country that lags behind most other Western countries in terms of the representation of women (cf. Henig and Henig 2001; Hughes and Paxton Reference Hughes and Paxton2008; Kenny and Verge Reference Kenny and Verge2016; Krook Reference Krook2009, 2010; Matland Reference Matland1998; Paxton Reference Paxton1997; Paxton and Kunovich Reference Paxton and Kunovich2003; Stockemer 2011). In fact, despite the fact that the percentage of women elected to state legislatures and the US Congress has ‘more than quadrupled’ over the past four decades (Cammisa and Reingold Reference Cammisa and Reingold2004: 181), women are currently still underrepresented in US legislatures at both federal and state levels (King Reference King2002). This lack of representation is especially visible at the federal level, where currently women only make up about 18 per cent of individuals serving in Congress, even though they account for 51 per cent of the US population.

Even though the US Congress is one of the least female-friendly legislative bodies in the world, a number of women have served in it. According to Gertzog (Reference Gertzog2002), there are three distinct ‘pathways’ that women have pursued to enter the US Congress and, more in general, develop political careers. In earlier years, the majority of women elected to Congress were either widows of deceased MCs or women who came from families of great wealth or with well-known regional or national political connections (Foerstel and Foerstel Reference Foerstel and Foerstel1996; Kincaid Reference Kincaid1978; Solowiej and Brunell Reference Solowiej and Brunell2003). Between 1966 and 1982 this picture began to change, and 58 per cent of all women elected to the US House of Representatives could be defined as ‘strategic politicians’ (Gertzog Reference Gertzog2002). Stating that female MCs are ‘strategic politicians’ has a number of implications in terms of candidate quality and decision to run (cf. Carson et al. Reference Carson, Engstrom and Roberts2007; Jacobson and Kernell Reference Jacobson and Kernell1983; Maestas and Rugeley Reference Maestas and Rugeley2008; Stone et al. Reference Stone, Maisel and Maestas2004). It also requires further thought in terms of determining their objectives, given the assumption of rationality (cf. Black Reference Black1972).

On the first issue, it has been determined that in the United States fewer women than men decide to run for public office, both in general (e.g. Rule Reference Rule1981) and in primary elections (Ondercin and Welch Reference Ondercin and Welch2009). In part, this decision may be a consequence of the fact that women perceive themselves as less qualified to run for office than men do (cf. Burns et al. 2001; Deckman 2004). More interestingly, however, it seems that, acting strategically, women tend to run for office only when open seats are available (Palmer and Simon Reference Palmer and Simon2001) and their chances of winning are higher, as no candidate enjoys the incumbency advantage (cf. Abramowitz Reference Abramowitz1991; Cox and Katz Reference Cox and Katz1996; Gelman and King Reference Gelman and King1990; Praino and Stockemer Reference Praino and Stockemer2012a, Reference Praino and Stockemer2012b; Stockemer and Praino Reference Stockemer and Praino2012). In fact, scholars have shown that even though women in politics seem to have to work harder than men in order to achieve similar outcomes (Fulton 2012), when women run for Congress they are as likely to win as their male counterparts (Burrell Reference Burrell1994; Palmer and Simon 2005). In this context, the incumbency advantage represents a real political glass ceiling that prevents women from entering Congress. It works like a gendered barrier in the political opportunity structure (cf. Bjarnegård and Kenny Reference Bjarnegård and Kenny2016), and is exacerbated by the highly strategic behaviour shown by female MCs (Carroll Reference Carroll1995; Palmer and Simon Reference Palmer and Simon2001).

Determining the objectives of these strategic female MCs is a slightly more nuanced task. Joseph Schlesinger’s (1966) seminal work on congressional ambition, as well as other interesting research on the topic (e.g. Brace 1985; Herrick and Moore 1993; Rohde 1979), posit that MCs display four types of ambition: (1) discrete ambition; (2) static ambition; (3) intra-institutional ambition; and (4) progressive ambition. MCs with discrete ambition only seek to serve their term and retire from public life. They have no interest in running for office again, including higher office. MCs with static ambition want to create for themselves a long political career within their current office (Schlesinger 1966). They tend to be inactive as legislators and focus most of their attention on their constituents, in a clear effort to secure re-election. MCs with intra-institutional ambition aspire to leadership positions within their current institution. Usually, they are keen to get their own legislation through and on toeing the party line, in an effort to ultimately obtain the leadership positions they aspire to (Herrick and Moore 1993). MCs with progressive ambition want to move on and try to be elected to higher office (Schlesinger 1996). They are usually very active but quite ineffective and keep a very large staff in order to prepare their careers for the move towards a higher office (Herrick and Moore 1993). While many existing works on ambition in the US Congress take into account the cost and/or risk of attempting election to higher office, the assumption that, if offered a higher office without any cost or risk, every MC would take it (Rohde 1979) is virtually ubiquitous in the literature. In other words, most existing works assume that MCs have progressive ambition (Fulton et al. 2006). Recently, Palmer and Simon (Reference Palmer and Simon2003) have shown, however, that female MCs display all the types of ambition described above. They go as far as measuring distinct characteristics of women with each category of ambition. In particular, they argue that progressive ambition is a common trait of female MCs from small states because their potential higher office constituencies coincide more with their current constituencies. They also argue that female MCs are more likely to run for higher office when there are open seats available and when they are in their mid-careers, so they do not have to sacrifice seniority. Ultimately, Palmer and Simon (Reference Palmer and Simon2003) and also Fulton et al. (2006) are suggesting that women are more strategic than men in their political ambition. Because female MCs are more strategic than their male counterparts, the incumbency advantage ultimately works against women as a group much more than against men (Carroll Reference Carroll1995), and the political ambition of most female MCs tends to be mostly static or intra-institutional, as it becomes progressive only under certain circumstances (Fulton et al. 2006; Palmer and Simon Reference Palmer and Simon2003). In this context, it becomes extremely important to understand what happens when women manage to break this incumbency glass ceiling and get elected to Congress. In particular, whether the careers of female MCs are any different from the careers of male MCs is a question that remains largely unanswered.

Lawless and Theriault’s (Reference Lawless and Theriault2005) study on career ceilings and female retirement in the US Congress makes a large step in this direction. It remains one of the only works explicitly focused on the issue of female service while in Congress. The authors find that female MCs are more likely to retire than their male counterparts when they cannot reach a position of influence (i.e. they reach a ‘career ceiling’). As a consequence, Lawless and Theriault (Reference Lawless and Theriault2005) conclude that female MCs enjoy shorter careers than males. Their work is based on Theriault’s (Reference Theriault1998) idea that MCs who reach a ‘career ceiling’ are more likely to retire than newly elected MCs or powerful long-serving MCs. In more detail, they find that, once seniority is accounted for, male and female MCs are equally likely to face career ceilings, but female MCs are more likely to retire and leave politics altogether, once they hit such career ceilings (Lawless and Theriault Reference Lawless and Theriault2005). To a certain degree, their entire argument hinges on the idea that ‘reaching a career ceiling is more dramatic for women than men because of gender differences motivating the decision to run for Congress’ (Lawless and Theriault Reference Lawless and Theriault2005: 585). Their interpretation of such differences in motivation is loosely based on Bledsoe and Herring’s (1990) well-known argument that ambition is a masculine characteristic (see Ruble Reference Ruble1983) that directly and significantly determines the behaviour of men, but not that of women. As in most existing works (e.g. Fulton et al. 2006), political ambition here is implicitly defined in terms of progressive ambition. Lawless and Theriault (Reference Lawless and Theriault2005) demonstrate that both men and women often reach career ceilings, but while males either tend to stick around because they get satisfaction from merely serving in Congress, or decide to run for higher office because of their (progressive) ambition (cf. Fox Reference Fox1997), women usually prefer to retire. Lawless and Theriault (Reference Lawless and Theriault2005) conclude then that female MCs will have shorter careers than male MCs. Instead, what they actually find is that female MCs have lower progressive ambition than male MCs. The ‘shorter career’ conclusion remains an untested and unexplored hypothesis.

VARIABLES AND DATA

We gauge congressional careers by how long men and women stay in Congress and whether or not they get nominated to important committees, utilizing two indicators as dependent variables. The first indicator is the number of years somebody stays in office. Lawless and Theriault (Reference Lawless and Theriault2005) have demonstrated that office tenure is not only an indication of a successful career, but also provides MCs with distinct powers, such as more influence in drafting legislation and influencing policy. The second indicator is the congressional committee that individual MCs join, as important committees help MCs achieve their career goals (Grimmer and Powell 2013).

Committee assignments are the result of a long and complicated interaction between individual preferences of MCs and preferences of the parties and party leaders who control the assignments (Leighton and Lopez 2002). Ultimately, however, recent scholarship shows that not only does the will of the party prevail, but also most member preferences are actually not accommodated by the parties (Frisch and Kelly Reference Frisch and Kelly2004). When it comes to female MCs, this relationship becomes reversed over successive terms, at least for Democratic women (Frisch and Kelly Reference Frisch and Kelly2003). Once an MC is part of a committee, she starts to accumulate seniority, and the more seniority an incumbent MC accumulates, the more likely it is that she will retain a committee assignment, even in the presence of substantial electoral loss by her political party (Grimmer and Powell 2013). In other words, MCs who are able to exploit the incumbency advantage and win multiple elections are often likely to reach and maintain a committee assignment that suits their ambition.

Abramowitz (Reference Abramowitz1991) refers to a number of committeesFootnote 1 as ‘re-election committees’. These committees provide their members with electoral and non-electoral advantages, including a higher likelihood of obtaining federal projects within their districts and the possibility of linking the economic interest of the committee to the deliberation of the committee itself (Bullock Reference Bullock1976). In other words, they provide their members with name recognition as well as pork and patronage to distribute, among other things. Re-election committees can be valuable to MCs with different types of ambition as they are perceived as assisting with re-election.

According to Smith and Deering’s (1997) classification of congressional committees, the most influential committees in the US House of Representatives are Appropriations, Budget, Rules, and Ways and Means. These four committees are known as ‘prestige committees’. They affect every member of the House and provide their members influence and prestige that go beyond serving constituents or pursuing personal policy interests (Smith and Deering 1997). MCs with intra-institutional ambition and MCs with progressive ambition will be particularly interested in serving in these committees, the former in order to solidify their power within their political party, the latter in order to utilize their prominence in their pursuit of higher office.

We include in our analysis both membership in re-election committees and membership in prestige committees.Footnote 2 We compiled data for these indicators for all US House of Representatives elections held between 1972 and 2012, utilizing data from the clerk of the US House of Representatives and some data shared with us by other scholars.Footnote 3

Our independent variable of interest is the dichotomous variable Female MCs, coded 1 for all female MCs who were successfully elected, 0 otherwise. As gender is not the only variable that influences political careers, we also include in our analysis additional relevant covariates.

Personal Characteristics

Age at First Election is the age of successful candidates at the time of election. In line with previous research (e.g. Brace Reference Brace1985; Frantzich 1978; Moore and Hibbing Reference Moore and Hibbing1992), we believe that politicians who are elected at a relatively young age (between 30 and 40) have sufficient time to advance in their congressional careers. Moreover, older freshmen MCs also seem unlikely candidates to be nominated to important committees. Education is an ordinal variable coded 1 for MCs with high school education or lower, 2 for MCs with a bachelor’s degree, 3 for MCs holding master’s degrees, and 4 for all MCs in possession of a doctorate. We assume that MCs with higher levels of education (cf. Docherty Reference Docherty2005; Studlar et al. Reference Studlar, Alexander, Cohen, Ashley, Ferrence and Pollard2000) have the necessary qualifications for a long and successful congressional career. Finally, Republican MCs is a dichotomous variable coded 1 for all Republican MCs, and 0 otherwise. It controls for differences in party affiliation, as they exist in terms of both committee assignment (Frisch and Kelly Reference Frisch and Kelly2003) and career length (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones Reference Box-Steffensmeier and Jones1997).

Electoral Controls

Personal Advantage is the margin of vote obtained by each candidate at the previous election. It accounts for the personal electoral strength of individual MCs (Abramowitz Reference Abramowitz1991). The covariates Incumbent Expenditures, Challenger Expenditures and their respective squares are the total dollar amount of the electoral expenses of elected MCs and their opponents and the same value squared, to control for the non-linear relationship between campaign expenditure and electoral success (cf. Abramowitz Reference Abramowitz1991; Jacobson Reference Jacobson1978, Reference Jacobson1990). The variable Opponent Score is an ordinal variable coded 1 for opponents who never held elective office, 2 for opponents who held elective offices, 3 for opponents who were state legislators in the past, and 4 for opponents who were former members of the US House of Representatives. It is directly based on Jacobson’s (Reference Jacobson1989) challenger scores that rank the ‘quality’ of individuals running against incumbents based on their political experience and the understanding that more formidable opponents may attract more votes, therefore diminishing the magnitude of the electoral success of incumbents, which, in turn, is likely to influence MCs’ careers in Congress. The variable Scandal Allegation is a dichotomous variable coded 1 for MCs subject to an investigation by the US House Ethics Committee, 0 otherwise. It accounts for the fact that several recent studies (e.g. Basinger Reference Basinger2013; Praino et al. Reference Praino, Stockemer and Moscardelli2013) have found that scandals have a high likelihood of ending an MC’s congressional career. District Partisanship is the district-level margin of victory/defeat of the most recent presidential candidate belonging to the same party of the successful candidate at each district. It has been utilized by a plethora of studies based on the US Congress (e.g. Ansolabehere et al. Reference Ansolabehere, Snyder and Stewart2001) as a good proxy of the underlying ideological/partisan tendencies of each congressional district. Our variable Adjusted ADA Distance gauges the distance between the score associated with the most ideologically extreme member of the political party of successful candidates and their own ADA score,Footnote 4 as adjusted by Anderson and Habel (Reference Anderson and Habel2009). Being a measure of conformity to the overall voting of each individual MC to the votes of other members of their own party, this variable controls for party loyalty, which has been identified by scholars as an important determinant of both committee assignment (Lee Reference Lee2008; Leighton and Lopez 2002) and length of political career (Theriault Reference Theriault1998). Finally, we create a dummy variable called Region South coded 1 for all states in the Southern RegionFootnote 5 of the United States and 0 otherwise, in order to account for the particularities of the American South.

Institutional Ambition Controls

Leadership positions within the legislative political parties and/or within the US Congress in general (e.g. committee chairmanships or minority party ranking within such committees) are sought by MCs as they progress in their political careers, according to the specific type of ambition they display (cf. Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005). Political parties have the most power in determining individual MCs’ assignments to committees, and such power increases when their party is in the majority (Heberlig and Larson Reference Heberlig and Larson2012). In essence, it is reasonable to expect that if an MC holds a leadership position or a prestigious appointment, she will have a large incentive to continue her career (Hall and Houweling 1995). Therefore, we computed a number of dichotomous covariates that take these factors into account. Leadership Position is coded 1 for all MCs who hold a leadership position either within the party or within the House Committee structure.Footnote 6 Majority Party Leaders and Minority Party Leaders are coded 1 for all MCs who serve in the Congressional party leadership (i.e. the speaker of the House and the majority/minority leaders and whips). Finally, Majority Party MCs is coded 1 for all MCs who belong to the majority party in the House at each relevant point in time.

Interaction Terms

In order to assess whether gender plays a direct role in determining the length and importance of the political careers of MCs or moderates the effect of other variables, we also compute a number of variables by interacting our gender variable with other dichotomous variables. These interactions are fundamental in order to rule out the possibility of gendered effects within the relationships we describe.

METHOD

We test the hypothesis that female MCs enjoy shorter careers than male MCs by employing a three-step process. First, we descriptively analyse the average number of years each of the two genders has spent in Congress. Second, we run a Kaplan–Meier test to see if the probability of survival is different for the two genders. Third, we estimate an event history model to measure the duration in years until the end of an MC’s tenure.Footnote 7 Event history analysis has proved to be an appropriate technique for studying leadership duration (cf. Ferris and Voia Reference Ferris and Voia2009; Kerby Reference Kerby2011). In particular, this technique allows us to measure the influence of an MC’s gender and her personal and circumstantial characteristics on the time it takes her to leave her elected office. Because we are measuring the duration that each MC stays in Congress, we average all independent variables over this time period.Footnote 8

We also engage in a three-step process, repeating each step for both assignment to re-election committees and assignment to prestige committees, in order to test the hypothesis that male and female MCs have different careers within the US House. First, we measure the total number of individuals who have served in these types of committees from 1972 to 2012. Second, we calculate and analyse the percentage of men and women who served in one of these committees. Third, we estimate two separate time-series logistic regressions to determine whether there is a difference in the two genders’ likelihood of being nominated to either a re-election committee or a prestige committee.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In our data set, 1,818 individuals have served in the US Congress, with 1,623 being men and 195 women. Men, on average, seem to stay longer in the House than women, with an average tenure of slightly more than 10 years (five terms), against an average of 7.8 years (less than four terms) for women. An independent samples t-test confirms that this difference in tenure is statistically significant (t=4.07, p=0.000). Hence, at first glance, our results indicate that there is, in fact, a bias toward longer careers in favour of men in the US Congress (see Table 1).

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics Measuring Average Tenure of Male and Female House Members

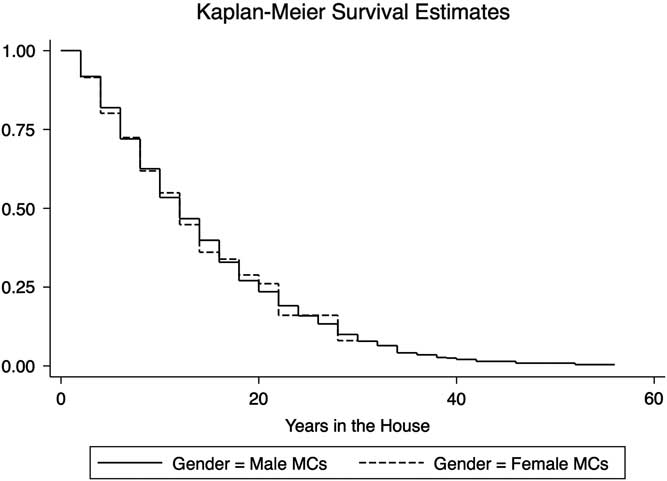

Our Kaplan–Meier estimation, however, does not confirm this finding. Comparing the line displaying the survival rate of women with the line showing the survival rate of men, we see that up to about 30 years there are no differences between the two genders pertaining to their likelihood of staying in office. Rather, the differences between the two genders only become pronounced after 30 years. While up to 2012 the longest any woman had served in the US House was 30 years, there were almost 100 men who had served 30 or more years. By right censoring our data, the Kaplan–Meier estimation accounts for the fact that women have only recently joined Congress in larger numbers and hence cannot have the same long careers men have enjoyed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 The Survival of Males and Females in the US House of Representatives

In fact, men with long congressional careers drive the descriptive statistics and the means test by giving men an edge. The corresponding log rank test also confirms that the two curves are not statistically different from one another (χ2=1.12, p=0.28). Hence the seemingly positive relationship between male gender and longer careers is an artefact of the data and of the fact that women have only entered the House in larger numbers relatively recently. For example, around 40 per cent of the women who served in the House between 1972 and 2012 had not finished their tenure and were still serving there in 2012. If we compare this high percentage to the meagre 20 per cent of men whose congressional careers had not come to an end in 2012, it is likely that in 10 or 20 years, there will be women with a House tenure of 35 or 40 years, as well.

Table 2 confirms the Kaplan–Meier estimation. Our dummy variable for female MC is not statistically significant. The positive sign of the coefficient implies that being female increases an MC’s chances of exitFootnote 9 compared with her male colleagues. However, the coefficient is not statistically significant and too small to make any meaningful difference.

Table 2 The Event History Model Measuring the Influence of Gender on House Members’ Tenure

Note: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

All the statistically significant control variables have the expected sign: MCs who tend to receive large electoral margins and spend large amounts of money during campaigns are less likely to leave the US House; MCs who tend to face more formidable opponents who spend large amounts of money, as well as MCs first elected at an older age, have a higher probability of leaving the US House. Our institutional controls show that MCs in leadership positions, as well as those who serve in prestige committees, are less likely to see their House careers ended. They also show that MCs serving in re-election committees are more likely to exit the House.Footnote 10 None of the interaction terms we included in the model is statistically significant, suggesting that there are no gendered differences in the relationships discussed above between career length and party leadership status, service in important committees, or party affiliation.

Table 3 illustrates that 61 per cent of all men in our sample at one point or another of their career managed to get assigned to a re-election committee, while 31 per cent served in a prestige committee. It also shows, however, that 57 per cent of all women managed to be part of a re-election committee, and 31 per cent served in a prestige committee. In brief, the descriptive data show that there is no difference in assignment to prestige committees between male and female MCs, while men appear to have a small edge over women within re-election committees. Yet, two independent samples t-tests (t=0.05, p=0.96; and t=0.91, p=0.36, respectively) show that there is no statistically relevant difference in either case.

Table 3 Descriptive Statistics Measuring Re-Election Committee Assignments of Male and Female House Members

Table 4 provides some additional information on these data. In fact, Table 4 gathers the percentage of all male and female MCs who became part of a re-election committee or of a prestige committee after each election included in our analysis. The percentage of female MCs serving in one of these highly desirable committees generally increases throughout the years. More interestingly, the table shows that in most election years the percentage of female MCs serving in one of these types of committees is at least comparable to the percentage of male MCs obtaining the same desirable assignment.

Table 4 Percentage of All Males and Females Serving in Congressional Committees, 1972–2012

Clearly, our descriptive data do not present any evidence in support of any kind of female disadvantage in terms of assignment to important congressional committees. On the contrary, it may be pointing in the opposite direction, especially for more recent years, with women having an advantage in relation to their male colleagues. Our multivariate analysis somewhat confirms this picture (see Table 5). In the two models, our independent variable of interest Female MC indicates that, overall, women are just as likely as menFootnote 11 to serve in a re-election or a prestige committee.

Table 5 Time-Series Logistic Regression of Assignment to Congressional Committees

Notes: #p<0.1; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Both models include Congress-specific dummy variables that are omitted from the results for presentation purposes. The 113th Congress is utilized as baseline.

A probability transformation of the results of our logistic regression helps to put our findings in perspective. In fact, keeping all other variables at their mean – and setting all dichotomous controls to 0 – our model predicts that the probability that a female serves in a re-election committee stands at around 17 per cent, while the probability that a male serves in the same type of committee is only 8 per cent. On the contrary, the probability of a female serving in a prestige committee is 13 per cent, while that of a male serving in the same type of committee stands at 15 per cent. In other words, our model is predicting that women have a slight advantage when it comes to serving in re-election committees and essentially exactly the same likelihood as their male colleagues of serving in prestige committees.

Our logistic regressions also indicate that MCs with a history of larger electoral margins are less likely to be assigned to re-election committees but more likely to end up in prestige committees, which appears to be an indication that those with high electoral margins do not need an assignment to a re-election committee and can dedicate time to consolidate their power and influence within the House (cf. Abramowitz Reference Abramowitz1991; Smith and Deering 1997). This finding, in particular, provides some context to the finding presented above that MCs serving in re-election committees tend to have shorter careers than other MCs. Our results also show that the larger the ideological distance between MCs and the most ideologically extreme member of their party, the more likely they are to serve in a re-election committee, but the less likely they will be to serve in a prestige committee. Finally, MCs with higher levels of education seem to be less likely to serve in re-election committees.

Our institutional ambition controls show that MCs affiliated with the majority party are less likely to serve in re-election committees, while both majority and minority party leaders are less likely to serve in prestige committees. In conclusion, our interactions show that there are no gendered differences between party lines in terms of assignment to important committees.

Overall, it seems that women not only have equal chances of winning electoral races (cf. Dolan Reference Dolan2008), but also have very similar political careers in the US House to those of their male colleagues. In fact, between 1972 and 2012, our data show that 28 per cent of all men who served in the House and 34 per cent of all women never served in either an electoral or a prestige committee. In other words, around 30 per cent of male and female MCs reached some sort of ‘career ceiling’ within the House. Statistically, this difference is negligible, as confirmed by an independent samples t-test (t=1.7, p=0.09). In addition, the opposite is also true. Around 20 per cent of all males who serve in the House during the same time period and 22 per cent of females served throughout their careers in both a re-election and a prestige committee. Once again, such a difference is not statistically relevant (t=0.8, p=0.4). In other words, almost identical percentages of males and females essentially seem to achieve very little while in the House, while identical numbers of both genders manage to rise to the most prestigious, advantageous and influential positions. Overall, female MCs and male MCs appear to have extremely similar careers within the US House of Representatives.

CONCLUSION

The issue of female representation in national legislative bodies is not only symbolic, it is also substantive (see Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967). Existing scholarship (e.g. Arceneaux Reference Arceneaux2001; Celis Reference Celis2009) has clearly shown that the presence of women in prestigious political positions increases the chance that policy debates and bills discussed focus on issues of importance to women. Consequently, meaningful gender equality can only be achieved if women occupy relevant policy positions within a given political system (cf. Swers Reference Swers2001). Mutatis mutandis, an underrepresentation of women is likely to create a lack of focus on women’s issues, policy preferences and concerns within the legislative process, thus creating a ‘gender gap’ in policymaking. In the previous pages, we show that men and women have similar political careers in the US House of Representatives in terms of both length of service and importance of their careers. In this light, female underrepresentation appears to be the consequence of a rigid and static political system that has created an incumbency glass ceiling (cf. Palmer and Simon Reference Palmer and Simon2001) that, together with other social forces, constitutes a gendered institutional barrier (cf. Bjarnegård and Kenny Reference Bjarnegård and Kenny2016) that prevents women from being elected to the US Congress. While our research ultimately posits that once women do get elected to Congress they then start to enjoy the protection of the same glass ceiling that was preventing them entering Congress, this does not mean that women are inevitably going to become adequately represented in the US Congress. In fact, the other social forces we mention (e.g. the fact that women are more strategic than men and feature different types of ambition) may continue to ensure that American women remain disadvantaged in politics in comparison to women in other countries. In fact, while our research rules out the existence of overt or covert gender discrimination within the US Congress when it comes to the career length and service of the two genders, it does not offer any insight on why, how and how many women consider running for Congress or public office in general. Knowing that when women get elected their careers are as lengthy and as successful as the careers of men is a good beginning. Nevertheless, much more work is needed in order to understand how to bring female representation in the United States to the same level as other developed countries.