In February 2000, an uproar arose when the conservative right Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) formed a coalition with Jörg Haider's Freedom Party (FPÖ).Footnote 1 Austria was ostracized. European Parliament members expressed their concern and the United States and Israel recalled their ambassadors from Vienna. However, in contrast to what many had perhaps hoped for, the populist right presence in Austria's government prepared the stage for similar coalitions in other countries. When the FPÖ – headed by the new leader Heinz-Christian Strache – was again invited into a government coalition in 2017, there was hardly any international condemnation.

This story illustrates an important political development that took place across Europe: populist radical right parties have become ‘normalized’ (Mudde Reference Mudde2019; Wodak Reference Wodak2020). Once censured as pariahs by most political elites, they are increasingly considered as suitable candidates to join governing positions (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, De Lange, Rooduijn, Akkerman, De Lange and Rooduijn2016; Fallend and Heinisch Reference Fallend and Heinisch2016). Several of them have entered governments, either as cabinet members, such as the Conservative People's Party of Estonia (EKRE), or as support parties of minority governments, like the People's Party (DPP) in Denmark. Alongside this ‘mainstreaming’ of the far right, another parallel development took place, too: former mainstream right-wing parties have radicalized. Two European Union member states – Hungary and Poland – are currently led by right-wing populist governments, raising concerns that both countries are turning into non-liberal democracies.

This article investigates the inclusion–moderation hypothesis: it asks to what extent the characterization of far-right populist voters as being disillusioned with the political establishment depends on whether their parties are in power or not. As far-right parties often campaign on dissatisfaction with the political establishment, one would expect a tension between their anti-elitist profile and government inclusion. After all, when they share government responsibility, the parties in question become part of the political establishment themselves (Cohen Reference Cohen2019).

Many studies have already investigated the electorate of what Jens Rydgren (Reference Rydgren2005: 414), among others, identified as the ‘new family’ of right-wing populist parties (Arzheimer Reference Arzheimer and Rydgren2018; Golder Reference Golder2016; Muis and Immerzeel Reference Muis and Immerzeel2017). Despite varying labels, it constitutes a group of similar parties – which this article will hereafter refer to as far-right parties. Scholars commonly distinguish three approaches to explain why people support far-right parties, namely economic grievances, opposition to progressive cultural values such as cosmopolitanism and multiculturalism (‘cultural backlash’) and protest against allegedly corrupt and unresponsive political elites (Golder Reference Golder2016; Ivarsflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). This article revisits the third explanation for far-right voting: ‘protest voting’, which we define as ‘voting for a party not because of the actual content of its electoral message but in order to “punish” other parties’ (Pop-Eleches Reference Pop-Eleches2010: 223).

Surprisingly, while public debates accentuate democratic decay in Central and Eastern European countries (CEECs), current empirical research on far-right parties is excessively centred on Western Europe and the United States. Addressing this remarkable gap, our main contribution is to investigate whether previous findings supporting the inclusion–moderation thesis that are based on Western Europe are equally valid in Central and Eastern Europe. We do so because current theories of far-right voting are Western-biased and do not necessarily match well with affairs in the post-communist region. For instance, Andrés Santana et al. (Reference Santana, Zagórski and Rama2020) conclude that anti-elitism is important to understand radical right populism in the West, but does not travel well to Central and Eastern Europe.

Our article mostly builds upon three recent studies. Focusing on Western Europe, Denis Cohen (Reference Cohen2019) and Hanspeter Kriesi and Julia Schulte-Cloos (Reference Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos2020) concluded that far-right parties in government attract fewer politically dissatisfied voters, compared to when those parties are in opposition. Similarly, Werner Krause and Aiko Wagner (Reference Krause and Wagner2019: 11) show that perceived political unresponsiveness increases support for populist parties, but this effect becomes less important as soon as a party is more established. Their study ‘goes beyond the universe of West European party systems’, yet only investigates voting choices in the 2014 European Parliamentary elections, which are typically described as second-order elections.

Our undertaking extends the scope of above-mentioned studies and investigates whether these conclusions are valid for national parliamentary elections between 2002 and 2016 in both Western and Central-Eastern Europe. In doing so, the broader aim of our study is what the replication typology of Jeremy Freese and David Peterson (Reference Freese and Peterson2017) denotes as ‘generalization’ (doing different analyses on new data).

We demonstrate and confirm that there is a cross-level interaction effect of far-right parties being in government or not on far-right voting: using European Social Survey (ESS) data (2002–16) and studying 22 European countries – including nine post-communist democracies – our findings show that political distrust indeed enhances far-right voting when these parties are in opposition. It is, however, a less important determinant of electoral support when far-right parties are in power. In a separate section, we zoom in on the interesting cases of Hungary and Poland. In both countries we observe that the far right's presence in power boosted the political trust of its voters, and moreover turned that political trust into a positive predictor of far-right voting. These two cases clearly contradict the common perception that political trust is negatively related to electoral support for the far right. Our findings underline that anti-elite populism is epiphenomenal to radical right politics, while its ideological core is formed by nationalism and/or nativism.

The populist far right: pro-people, anti-elite, exclusionary

Although discussing definitional matters in detail is beyond the scope of this article, the delineation of the kind of parties we study requires clarification: our study elaborates on three recent comparative studies, but each includes a differently labelled set of parties, namely far right (Cohen Reference Cohen2019), populist right (Krause and Wagner Reference Krause and Wagner2019) and radical right (Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos Reference Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos2020). Despite these differences, they largely investigated the same set of parties. Focusing on these same parties, we will briefly tidy up some conceptual unclarities.

Unfortunately, the European radical right populist party family is often described with the shorthand catchword ‘populism’ (Bonokowski Reference Bonikowski2017). This is confusing. As Margaret Canovan (Reference Canovan1984: 313) aptly points out, the only feature that all populists share is ‘a rhetorical style which relies heavily upon appeals to the people’. As such, it has no political colour. Rather, it is ‘a normal political style adopted by all kinds of politicians from all times’ (Jagers and Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007: 323). Similarly, Jan-Werner Müller (Reference Müller2016: 29) explains that ‘every politician – especially in poll-driven democracies – wants to appeal to “the people”; all want to tell a story that can be understood by as many citizens as possible, all want to be sensitive to how “ordinary folks” think and, in particular feel’.

Two additional features transform this ‘thin populism’ into a more fully fledged political narrative: anti-elitism and exclusionism (Jagers and Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007; Woods Reference Woods, Woods and Wejnert2014). First, thin populism can be extended with an anti-establishment discourse: populists often highlight that ordinary people are not represented by allegedly unresponsive, incompetent and self-enriching elites (Mudde Reference Mudde2007). Second, populist leaders frequently vilify minority groups and adopt an exclusionary form of ethno-nationalism (Bonikowski Reference Bonikowski2017; Müller Reference Müller2016). As Cas Mudde and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013: 166) explain, ‘even though the European populists claim to be the ‘voice of the people’, it is always an ethnicized people, excluding ‘alien’ people and values. The labels ‘radical right’ and ‘far right’ are used for such exclusionary populism, referring to the extreme position on issues related to immigration and ethnic diversity (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, De Lange, Rooduijn, Akkerman, De Lange and Rooduijn2016).

Anti-establishment rhetoric does not necessarily go hand in hand with exclusionism: scholars distinguish between exclusionary and inclusionary populist parties, such as Die Linke and Podemos (Krause and Wagner Reference Krause and Wagner2019; Rooduijn Reference Allen2017). The reverse is also true: radical right parties do not necessarily adopt anti-elitist populism. The Belgian Vlaams Blok and the French Front National are good examples. Both originated as ‘non-populist radical right’ parties in the 1970s and only later adopted anti-establishment rhetoric (Jagers and Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007). As Mudde (Reference Mudde2007: 49) explains, ‘the experience of semi-permanent opposition [has] brought most radical right parties to adopt populism’.

Besides its content, another issue is whether populism constitutes an ideology or a style (Rydgren Reference Rydgren2017; Woods Reference Woods, Woods and Wejnert2014). We argue that the two approaches – ideology vs. style – can be fruitfully combined. We concur with the ideational approach that certain ideological features seem indispensable, namely nativism (Rydgren Reference Rydgren2017). At the same time, we agree that anti-elitism is not a function of party ideology, but stems from the specific context in which parties operate. It is ‘a way of formulating political claims that is more likely to be employed by the same actors in some circumstances and not others’ (Bonikowski Reference Bonikowski2017: 186). Populists are not inherently anti-elitist, because they ‘have no problem with representation as long as they are the representatives; similarly, they are fine with elites as long as they are the elites leading the people’ (Müller Reference Müller2016: 29).

To conclude, this necessary conceptual detour argues that exclusionism constitutes a core component of far-right parties' ideology, whereas anti-establishment rhetoric is not, but nevertheless frequently appears because of the political context in which far-right parties operate. Our approach is selective regarding the exclusionary/inclusionary dimension and focuses solely on exclusionary parties. But it is inclusive regarding the anti-establishment dimension: we study all exclusionary parties, regardless of whether they also adopted anti-establishment rhetoric or not.

Why people support far-right parties: the role of protest votes

Following Wouter van der Brug et al. (Reference Van der Brug, Fennema and Tillie2000), we distinguish ideological and protest voting. Ideological voting focuses on the policy-related preferences that explain why people vote for the far right. These policy issues are commonly distinguished into economic and cultural approaches (Ivarsflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). Most importantly, they refer to people's concerns that immigration and ethnic diversity undermine their national culture and identity: many studies showed that anti-immigration attitudes most importantly predict electoral support for far-right parties (Brils et al. Reference Brils, Muis and Gaidytė2020; Ivarsflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Zhirkov Reference Zhirkov2014).

Ideological motivations may differ between post-communist and Western European democracies. More so than in Western Europe, Eastern European far-right parties are generally left-leaning on the economy and often mobilize on economic grievances surrounding welfare retrenchment (Bustikova Reference Bustikova and Rydgren2018). Moreover, the link between anti-immigration attitudes and far-right voting is much stronger in Western European countries (Allen Reference Allen2017; Brils et al. Reference Brils, Muis and Gaidytė2020; Santana et al. Reference Santana, Zagórski and Rama2020). This may be attributed to the fact that post-communist Europe lacks large-scale immigration, but the perceived fear of an influx of foreigners can be as ‘real’ as the actual experience of ethnic diversity in the West (Krastev and Holmes Reference Krastev and S2019). More so, the difference seems due to the widespread nationalist culture in Central and Eastern Europe in general, where it is ‘simply common sense’ that multiculturalism should be avoided – thus, far-right parties and their supporters hardly deviate in this regard from other parties and voters (Enyedi Reference Enyedi2020: 369).

A second approach to account for far-right support is ‘protest voting’ (Dalton and Weldon Reference Dalton and Weldon2005; Van der Brug et al. Reference Van der Brug, Fennema and Tillie2000). In contrast to ideological motivations, voters may be attracted to far-right parties because they want to express their dissatisfaction with the political establishment (Alvarez et al. Reference Alvarez, Kiewiet and Núñez2018; Pop-Eleches Reference Pop-Eleches2010). Similarly, Van der Brug et al. (Reference Van der Brug, Fennema and Tillie2000: 83) explain that ‘protest voters cast their vote not to affect public policies, but rather to express disenchantment with the political system or with the political elite’. Many scholars indeed find that far-right voting occurs more frequently among people who score higher on indicators of political disillusionment (Norris Reference Norris2005; Rooduijn, Reference Allen2017; Zhirkov Reference Zhirkov2014). Far-right voters also have a stronger feeling that their voice is not heard and political elites ignore ‘ordinary citizens’, compared with other voters (Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, Van der Brug and De Lange2016).

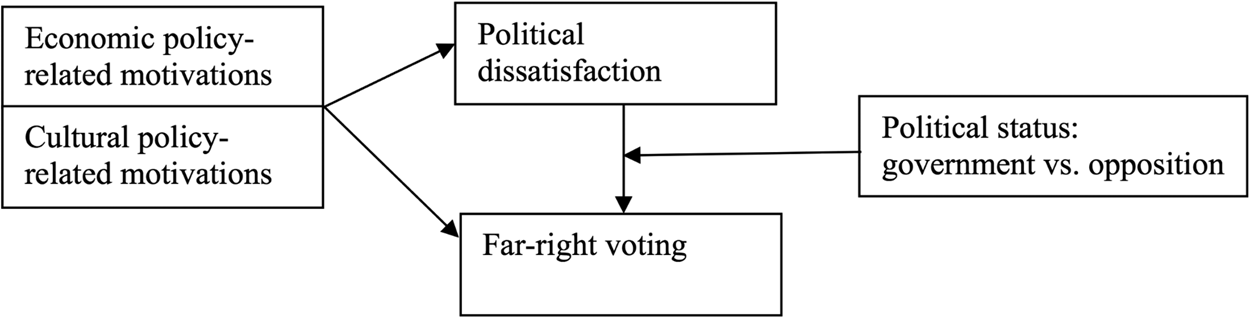

The more complicated element to proving protest voting is to demonstrate that a causal effect of political discontent on far-right support exists (Bergh Reference Bergh2004). As Kai Arzheimer (Reference Arzheimer and Rydgren2018: 146) explains, ‘the pure-protest thesis claims that radical right support is driven by feelings of alienation from the political elites and the political system that are completely unrelated to policies or values and hence have nothing to do with the radical right's political agenda’. Hence, we should assess whether there is any non-spurious effect of political discontent on voting behaviour once we control for policy-related motivations (Hernández Reference Hernández2018). Economic and cultural grievances could indeed act as confounding factors, as shown in the left-hand side of Figure 1.

Figure 1. Causal Model of Protest Voting

The inclusion–moderation hypothesis: parties' political status influences protest voting

The question remains why some citizens perceive a vote for far-right parties as a vote against the political establishment. The first obvious answer is that far-right parties tend to campaign on dissatisfaction with the political elite (Bélanger and Aarts Reference Bélanger and Aarts2006; Cohen Reference Cohen2019). Second, far-right parties have often been treated as ‘outcasts’ by political elites (Van der Brug and Fennema Reference Van der Brug and Fennema2007). Hence, both their anti-establishment rhetoric and mainstream parties' strategy of a cordon sanitaire make far-right parties a suitable option for voters who want to ‘scare the elite’ (Van der Brug et al. Reference Van der Brug, Fennema and Tillie2000: 83).

But what if far-right parties become more accepted by political elites and part of the political establishment? It then seems difficult to uphold the argument that far-right voters express their discontent with the political elite. The protest-voting argument is indeed conditional: political dissatisfaction has a weaker effect – or perhaps even no effect at all – on the likelihood to vote for far-right parties when these parties are included in the government. This interaction effect is shown on the right-hand side of Figure 1.

This idea that we will empirically test is not new. Three decades ago, Arthur Miller and Ola Listhaug (Reference Miller and Listhaug1990: 366) already suggested that giving protest parties a say in government could restore political trust among their supporters. They concluded that the rise of political confidence they observed among the Norwegian Progress Party (FrP) ‘seems to have occurred in response to the increased influence of the FrP in the political decision-making arena’. Similarly, Johannes Bergh (Reference Bergh2004) showed that political distrust no longer correlated with voting for the FPÖ when this Austrian far-right party was in government in 2000.

Recent case studies have likewise confirmed the inclusion–moderation hypothesis – FrP supporters' satisfaction with democracy significantly increased once their party assumed office (Haugsgjerd Reference Haugsgjerd2019), and the same happened for Alternative for Germany (AfD) supporters when their party entered the Bundestag after great electoral success (Reinl and Schäfer Reference Reinl and Schäfer2020).

Recent comparative studies also came to similar conclusions (Cohen Reference Cohen2019; Krause and Wagner Reference Krause and Wagner2019; Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos Reference Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos2020). Cohen (Reference Cohen2019) finds that, in contrast to far-right parties in the opposition, those that are in government fail to appeal to politically dissatisfied voters. His main analysis using data on European Parliament elections from the ESS (1989–2014) includes 10 Western European countries – in four of them the far right was included in the government coalition or supported a minority coalition (Austria, Denmark, Italy and the Netherlands).

Krause and Wagner (Reference Krause and Wagner2019) likewise examine voting behaviour in European Parliament elections. Studying various populist parties in 23 EU countries in 2014, they show that perceptions of political unresponsiveness (i.e. lack of external efficacy) enhance voting for populist parties, but the strength of this effect decreases the more the party in question is a well-established actor in the political system.

Similarly, Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos (Reference Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos2020) find that political dissatisfaction contributes significantly less to radical-right voting if the corresponding party is in government. Their analysis of ESS data (2002–16) includes 13 Western European countries, of which six experienced far-right party inclusion (Austria, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland).

To what extent are the above-mentioned findings equally valid if we investigate voting behaviour in national parliamentary elections in Central and Eastern Europe? Three decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, there are persisting political and socioeconomic differences between Western democracies and the post-communist region, primarily inflicted by the legacy of the communist rule and often traumatic transition to capitalist democracy (Pop-Eleches and Tucker Reference Pop-Eleches and Tucker2017).

In carrying out this investigation, our study's broader aim is to replicate previous results. Freese and Peterson (Reference Freese and Peterson2017) denote our specific aim as ‘generalization’ (doing different analyses on new data): we seek to strengthen a broader cross-regional interpretation of important prior conclusions. Remarkably, replicating earlier findings is generally applauded, but not frequently pursued. As Daniel Hamermesh (Reference Hamermesh2007: 715) notes, scholars generally ‘treat replication the way teenagers treat chastity – as an ideal to be professed but not to be practised’. We plea for chastity: we should focus more on the robustness, repeatability and generalizability of existing insights, instead of continually generating new hypotheses inspired by overrated notions of ‘innovativeness’ and ‘novelty’.

Two underlying causal logics: attitudinal change and sorting

Not surprisingly, the causal model (Figure 1) that we showed is similar to the causal models of the three studies that we replicate. Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos (Reference Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos2020) are most explicit about this underlying causal logic and present a very similar figure. But Cohen (Reference Cohen2019) and Krause and Wagner (Reference Krause and Wagner2019) likewise presume that political trust is a determinant of vote choice, not the other way around – which becomes evident from the fact that they investigate the ‘propensity of far-right voting’, rather than actual voting behaviour.

This causal logic can be called a ‘sorting effect’. According to this logic, the inclusion–moderation argument implies that voters with lower levels of political trust may start to vote differently once far-right parties are in power. Put differently, disgruntled citizens start to switch from far-right parties to other parties (or abstention) once the far right gets in power. Thus, weaker effects of political trust on far-right voting under far-right governments could be driven by the fact that far-right parties lose their ‘protest appeal’ among dissatisfied citizens. As Cohen (Reference Cohen2019: 5) puts it, ‘stronger and more successful far-right parties are less likely to appeal to dissatisfied voters’. At the same time, the political trust gap between far-right supporters and other voters can become narrower because voters with higher levels of political trust start to vote differently once far-right parties are in power and lose their ‘protest appeal’: they could switch from mainstream parties to far-right parties. To rephrase Cohen, stronger and more successful far-right parties are more likely to appeal to satisfied voters.

There is a second causal process that could explain why the association between political distrust and far-right voting changes when far-right parties find themselves in government, rather than in opposition: attitudinal change (Mauk Reference Mauk2020). This implies that far-right voters could become more trustful of political institutions once their parties get into government. The reverse might hold for people who do not support the far right: it is possible that other voters become less trustful of political institutions once the far right assumes power. Atle Haugsgjerd (Reference Haugsgjerd2019) points out that far-right government participation could decrease political distrust and alienation among dissatisfied sections of the population, but could at the same time have negative substantive policy effects in the eyes of many other, liberal-minded, citizens. Based on a recent study of 12 Western European countries, Eelco Harteveld et al. (Reference Harteveld, Kokkonen, Linde and Dahlberg2021: 131) conclude that the opponents of far-right parties ‘have built up a buffer of political support’ that prevents a decline in trust when the far-right parties enter governments. This may be true for Western Europe, but most post-communist countries clearly lack such a ‘buffer’. Political trust in Central and Eastern Europe is low, mainly because of the (poor) quality of institutions, pervasive corruption and general suspicion (Gaidytė Reference Gaidytė2015).

Thus, paradoxically, we would expect an asymmetrical attitudinal change – an increase of trust among far-right voters does not go hand-in-hand with a decrease of trust among other voters – for the opposite reason: the glaring lack of trust in political institutions makes it unlikely if not impossible to observe an even further decline in trust.

To conclude, both underlying causal dynamics, or some combination of the two, are compatible with the results reported in previous studies (Cohen Reference Cohen2019; Krause and Wagner Reference Krause and Wagner2019; Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos Reference Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos2020) since the analyses are based on cross-sectional data.

Methods

Data and case selection

This study uses ESS data of eight waves between 2002 and 2016 (rounds 1–8).Footnote 2 We included only country-rounds that contained voters for a far-right party. The resulting sample comprises 131,934 respondents (of whom about 10% voted for a far-right party). Our sample contains 22 countries.Footnote 3 For information about which party was in opposition/government and party size we relied on the Parliaments and Governments (ParlGov) database (Döring and Manow Reference Döring and Manow2019).

Dependent variable

Based on respondents' vote choice – which party they voted for during the last national general elections – we grouped voters into two categories: far-right voters and voters for all other parties (including blank votes). Respondents who abstained or were not eligible to vote are excluded from the analysis.

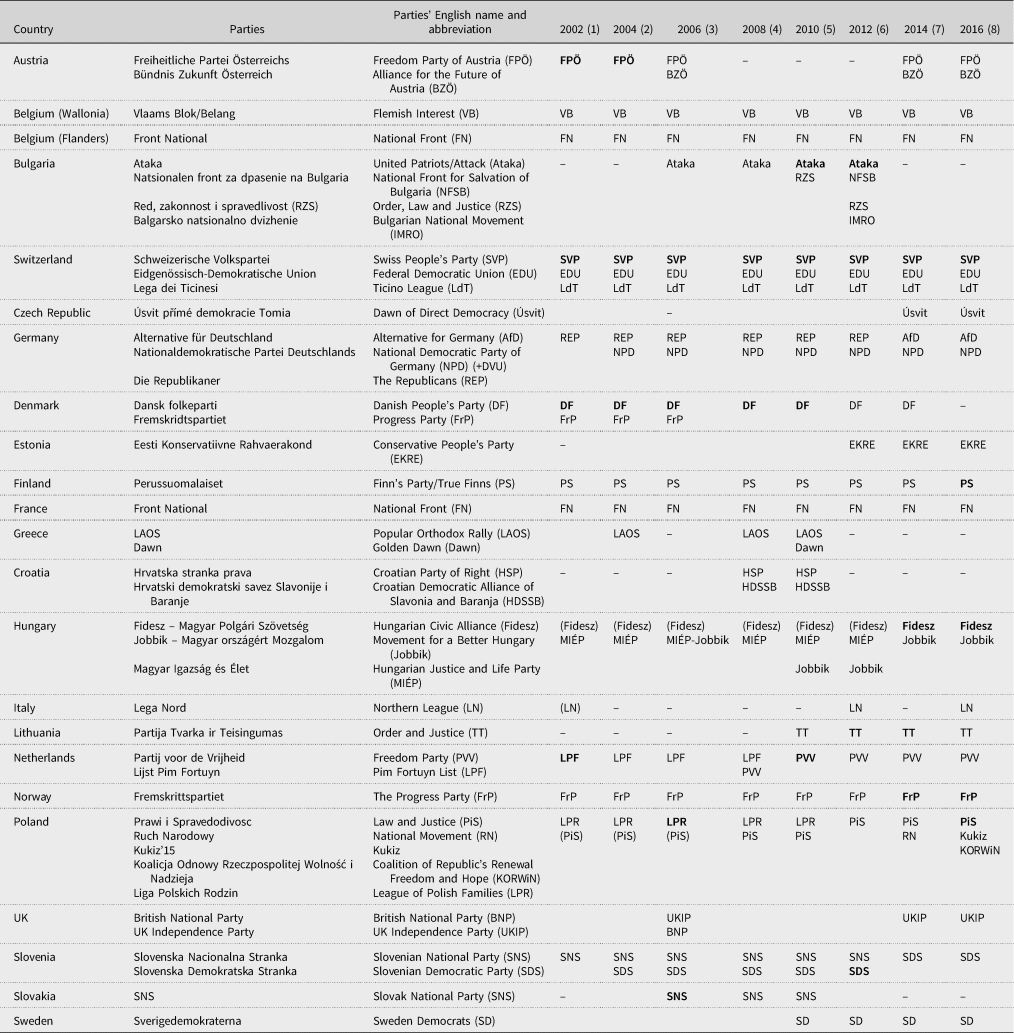

Table 1 shows all country-rounds and far-right parties. As we replicate Cohen (Reference Cohen2019), Krause and Wagner (Reference Krause and Wagner2019) and Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos (Reference Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos2020), we assessed whether our selection matches their categorizations of ‘far-right’, ‘right-wing populist’ and ‘radical right’ parties, respectively. This assessment is reported in the Online Appendix and concludes that there is a strong agreement about which parties belong to the far-right family.

Table 1. Far-Right Parties of 22 European Countries

Source: ESS (2002–16).

Notes: – means the country is not available in ESS. Party abbreviation in bold: government participation of far-right party during (a part of) ESS fieldwork period. Party abbreviation in parentheses in columns 4–11: mainstream party, not yet far right.

Due to their electoral strength and political power, two important cases are Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland and Fidesz in Hungary. They originated as conservative right-wing parties, but scholars have increasingly defined them as ‘radicalized parties’ (Bustikova Reference Bustikova and Rydgren2018; Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2017). According to experts of the PopuList 2.0 (Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, Van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019), PiS and Fidesz turned into far-right parties in 2005 and 2010, respectively – interestingly, they are not marked as borderline cases, which implies that these experts agree about these particular changes. We consider respondents who reported to have voted for PiS or Fidesz during the 2005 and 2010 elections, respectively, not (yet) as far-right voters, but only so from the general elections in 2007 (Poland) and 2014 (Hungary) onwards.

Individual-level explanatory variables

Protest voting

The measurement of the main predictor in this study – political dissatisfaction – consists of three questions that ask respondents to which extent they have trust in politicians, political parties and the country's parliament.Footnote 4 They constitute a reliable scale: Cronbach's α ranges between 0.86 (Switzerland) and 0.93 (Czech Republic). A higher score indicates more confidence in political institutions.

Ideological voting

Concerning policy-related motivations, we distinguished cultural and economic issues. Voters' views on immigration are tapped with three questions that ask if immigrants are ‘good or bad for the economy’, ‘undermining or enriching cultural life’ and ‘make the country a better or worse place to live in’. The answer categories run from 0 to 10, whereby a higher score stands for stronger anti-immigration attitudes. The scale is reliable: Cronbach's α ranges from 0.77 (the Netherlands) to 0.89 (United Kingdom).

Citizens' adherence to authoritarian values is operationalized by five items about topics concerning security and conformity. Respondents needed to indicate to what extent the description of a certain person applied to them, for instance: ‘It is important to her/him to that the government ensures her/his safety against all threats.’ The answer categories ranged from ‘not like me at all’ (0) to ‘very much like me’ (5). Reliability analyses show that the Cronbach's α of the scale ranges between 0.62 (Hungary) and 0.76 (Lithuania).Footnote 5

Next, respondents' support for income redistribution is measured with the item ‘government should reduce differences in income’. The answers range from ‘disagree strongly’ (0) to ‘strongly agree’ (4). Dissatisfaction with the performance of the national economy is also measured, whereby a higher score means that people are more negative in their assessment (0 = ‘extremely satisfied’; 10 = ‘extremely dissatisfied’).

Not all above-mentioned items directly gauge citizens' attitudes towards concrete policy issues; for instance, anti-immigration attitudes do not directly tap agreement with certain measures to limit immigration. Yet, we assume these variables are suitable proxies of policy-related motivations for far-right voting.

Socio-demographic background

Our study controls for several socio-demographic factors. First, we include respondents' subjective income, namely, how respondents judge their capability to live with their current income (ranging from ‘very difficult’ (0) to ‘living very comfortably on present income’ (3)). Furthermore, we constructed a dummy variable indicating unemployment, based on respondents' reported main activity. Respondents' educational level is measured with five categories: (0) less than lower secondary education; (1) lower secondary education completed; (2) upper secondary education completed; (3) post-secondary non-tertiary education completed; (4) tertiary education completed.Footnote 6 We also control for religiosity – ranging from ‘not at all religious’ (0) to ‘very religious’ (10) – and political interest – ranging from ‘not at all interested’ (0) to ‘very interested’ (3). Furthermore, a dummy variable ‘residential urbanization’ scores 1 when people indicate that they live in a big city, suburbs of a big city or town/small city. We treat the other answers ‘farm or home in countryside’ and ‘country village’ as rural residential area (0). Lastly, we control for age and sex.

Macro-level variables

Far-right government participation

Our main contextual variable is far-right government participation, which we operationalize as a far-right party being in the government coalition or when it is formally supporting a minority cabinet (Cohen Reference Cohen2019). This macro-level variable is obtained from the ParlGov data.

Generally, respondents who are interviewed during a certain country-round answer questions about politics while the same government is in power – most of the time, the government did not change during the fieldwork. Unfortunately, matters are not always so straightforward. Sometimes a new government is installed during the ESS fieldwork period, and a particular ESS round can thus cover two different political contexts. For instance, in the Netherlands a minority cabinet with support agreement of Wilders' Party for Freedom (PVV) was installed on 14 October 2010 (Rutte I), so that Dutch respondents' of the fifth ESS wave can be split into two distinct groups. The first group of respondents answered the survey questions about trust in politics during the Balkenende VI cabinet, whereas the second group was interviewed after the instalment of the Rutte I cabinet.

The opposite also occurs sometimes: consecutive ESS rounds cover the same government. In Bulgaria, for example, the data collection of rounds 5 and 6 (2010–12) took place when the same Borisov I minority government was in power, supported by Ataka.

To split the ESS rounds based on governmental terms, we used the interview date of each respondent to determine which cabinet was in power.Footnote 7 Consequently, multiple cabinets can occur per country within the same ESS round. Taking both ESS rounds and governmental terms into account, we constructed units of analysis that we call ‘country-periods’. Table A1 in the Online Appendix depicts the 32 country-periods when the far right was in power, based on 21 cabinets with far-right inclusion.Footnote 8

The far-right parties in our study have formed coalitions or supported governments in six Western European (cf. Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos Reference Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos2020) and six Central-Eastern European countries (Bulgaria, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia), mainly with centre-right parties. The political colour of these governments is more mixed in CEECs: in Lithuania and Slovakia, far-right parties have formed coalitions with social democratic parties.

We need to add two clarifications about government participation. First, our categorization of ‘far-right governments’ omits so-called caretaker governments that are temporarily put in place when a government steps down. They are usually limited in their function, serving only to maintain the status quo (rather than propose new legislation) until the formation of a new government. Far-right parties sometimes formally act as ‘caretaker’ parties, but we will not treat these instances as far-right cabinets. We make one exception for one case in Austria, because a caretaker cabinet (Schuessel II) was an interim period between two far-right governments (Schuessel I and Schuessel III).

Second, we do not consider the Hungarian Orban II government, formed after the 2010 elections, as a far-right government, nor the Kaczynski government in Poland following the 2005 elections. We assume that Fidesz and PiS gradually radicalized and both governments were not far right in character immediately from the start. For the same reason, as we explained above, we do not consider people who voted for Fidesz and PiS in the elections of 2010 and 2005, respectively, as far-right voters.

Electoral strength of the far right

Far-right parties that have been included in governing coalitions received comparatively large seat shares (Best Reference Best2019). And in its turn, how many parliamentary seats far-right parties have is possibly correlated with how much confidence far-right supporters have in politics. We therefore control for the electoral strength of the far right. Relying on ParlGov data, we calculated the relative amount of parliamentary seats of all far-right parties during each specific period.

We looked at the outcomes of the national elections that are connected with the current government – that is, the ruling government at the moment when respondents were interviewed. Therefore, the far right's electoral strength does not always overlap with the results of the most recent elections at the time of the interview. Our decision to adopt governmental terms as units, as we explained above, implies that the electoral strength changes when a new government is installed, but not immediately after the elections.Footnote 9

Results

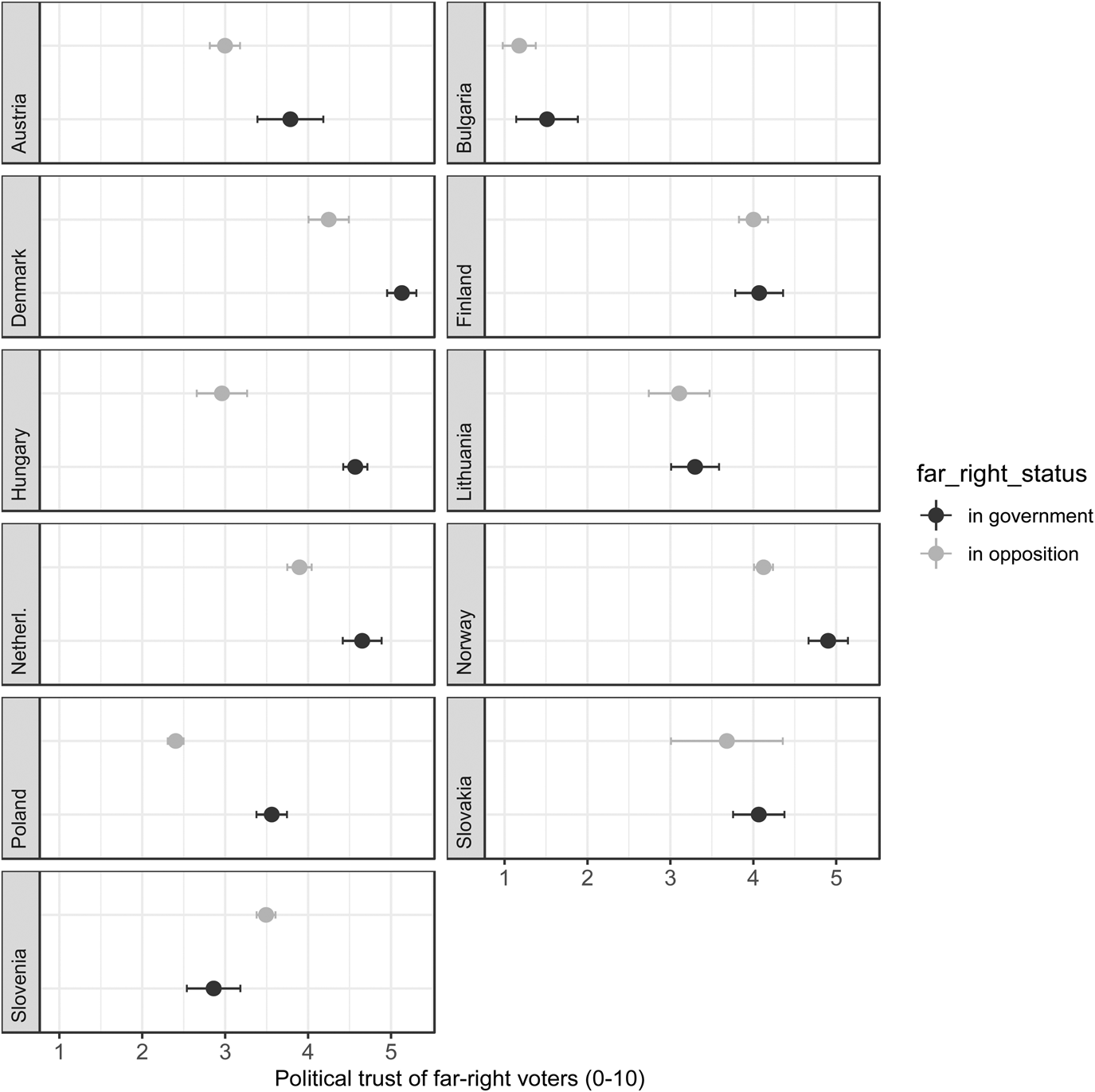

Let us first have a look at the descriptive statistics.Footnote 10 Since we predict that far-right voters are less politically disgruntled when their parties are in power, we focus on levels of political trust, broken down into the political status of the far right (in opposition vs. in government) and respondents' voting behaviour (far-right party vs. other parties or blank). In line with the inclusion–moderation hypothesis, European far-right voters (N = 13,330) have considerably more trust in politics when the far right is in power (M = 4.45; SD = 2.22), as opposed to being in opposition (M = 3.23; SD = 2.06).

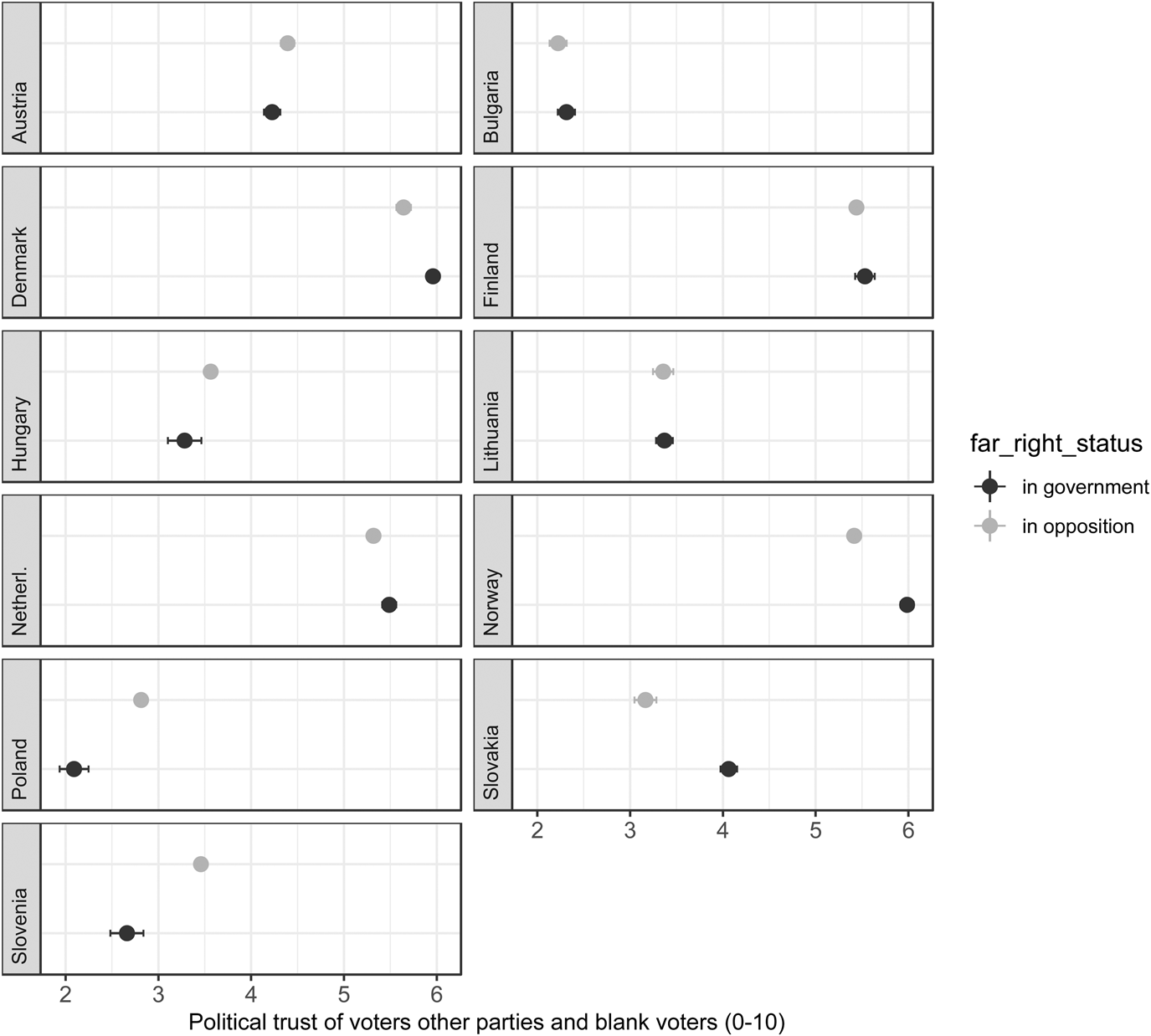

As we explained in the theoretical background, the political trust gap between far-right supporters and other voters might also become narrower because of declining trust among those who do not support the far right. Remarkably, however, all other voters (N = 118,604) have overall likewise more trust in politics when the far right governs (M = 4.84; SD = 2.19) than when it is in opposition (M = 4.27; SD = 2.14), although this difference is less pronounced. This indeed suggests that the inclusion of far-right parties is not necessarily negatively associated with political satisfaction among the electorate (Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld, Kokkonen, Linde and Dahlberg2021).

For a more controlled comparison, we turn to political trust per country for those countries that experienced both governmental inclusion and exclusion of the far right (see Figure 2). It confirms that far-right voters are generally less politically disgruntled when their party is in power – we particularly observe large differences in Hungary, Slovakia, Denmark and Norway.Footnote 11 If we switch our attention to all other voters (see Figure 3), the picture is more mixed.Footnote 12 Interestingly, in four countries (Slovakia, Denmark, Netherlands, Norway) other voters had, just as far-right supporters, significantly more trust in politics when the far right was in the government.

Figure 2. Political Trust of Far-Right Voters (Means), Broken Down by Far-Right Party's Status (in Government vs. in Opposition), per Country

Figure 3. Political Trust of Voters of Other Parties and Blank Voters (Means), Broken Down by Far-Right Party's Status (in Government vs. in Opposition), per Country

In contrast, in Austria, Hungary and Poland far-right voters are significantly less dissatisfied when their party is in power, whereas the remainder of the electorates are significantly more dissatisfied, compared with other types of governments. Slovenia is an exceptional case: in this country both far-right voters and other voters had less political trust when the far-right Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS) was included in the government in 2012. Finally, we do not observe any mean differences in Bulgaria, Finland and Lithuania between the two conditions (far right in government vs. in opposition).

Both underlying causal dynamics (attitudinal change and sorting), or some combination of the two, are compatible with the results reported. Attitudinal change implies that political trust is endogenous, in the sense that government participations lead to attitudinal changes (among far-right voters and/or other voters). Sorting treats political trust as exogenous: political trust levels among the electorate remained stable, but only the voters' distribution changes. The observation that in several countries the overall level of political trust is substantially higher when the far right is included in the government suggests that attitudinal changes are at work, although we need to be very careful with causal interpretations of this difference. We return to this issue later.

We continue with multilevel binary logistic regressions to explain far-right voting. The results are presented in Table 2, which shows the odds-ratios (OR). All other voters (including ‘blank votes’) are the reference category. The independent variables are standardized (mean is 0 and standard deviation is 1).

Table 2. Multilevel Binary Logistic Regressions of Far-Right Voting (Other Party or Blank Voters Are the Reference Category)

Notes: OR: odds-ratios. Coefficients in bold are statistically significant (p < 0.05, two-tailed). Models 1–4: N 1 = 131,934; N 2 = 139 country-periods; Model 5A: N 1 = 95,626; N 2 = 95 country-periods; Model 5B: N 1 = 36,308; N 2 = 48 country-periods. Model 6A: N 1 = 44,251; N 2 = 43 country-periods; Model 6B: N 1 = 29,658; N 2 = 40 country-periods.

Model 1 shows how political trust is associated with far-right voting for a model with only socio-demographic control variables. It tentatively supports the protest-vote explanation and shows that politically more trustful citizens vote less often for a far-right party than people who are less trustful.

Model 2 adds policy-related motivations. Except for people's evaluation of the national economy, they all significantly predict far-right voting. In line with previous studies (e.g. Brils et al. Reference Brils, Muis and Gaidytė2020), people's views on immigration are most important: voters who strongly advocate open borders are less inclined to cast their vote for the far right, whereas the odds are much higher for those who strongly prefer border closure. Moreover, the results reconfirm the protest-voting explanation: besides policy-related factors, political distrust still provides an additional motivation that explains why some Europeans are more inclined to vote for far-right parties than others.

Subsequently, Model 3 assesses to what extent the influence of political discontent is context-dependent. We added the dummy variable ‘far right in government’ and the multiplicative interaction term of the far right's political status (government vs. opposition) and political trust. The outcomes show that the association between political distrust and far-right voting is significantly weaker when these parties share government responsibility, instead of being in opposition.

As expected, the probability that people have voted for the far right is higher when far-right parties are currently in power. This matches Robin Best's (Reference Best2019) observation that far-right parties that have been included in governing coalitions received comparatively larger seat shares. Hence, a stronger parliamentary voice, rather than government inclusion itself, could be responsible for the significant inclusion–moderation effect we found in Model 3. Therefore, we have included an interaction term of electoral strength with political trust as a control variable. Model 4 shows that the electoral strength of the far right (the share of parliamentary seats) indeed has a considerable positive effect on the likelihood of voting for the far right. More importantly, our findings demonstrate that both government inclusion and a stronger parliamentary representation make far-right voters less disgruntled about politics, compared with all other voters.

Next, Models 5a and 5b are separate models for two sets of countries: they demonstrate the similarities and differences between Western European countries (WECs) and CEECs. These findings reveal some interesting differences between the two regions regarding the characteristics and motivations of far-right voters – for instance, Eastern European far-right voters are more religious and more in favour of income redistribution compared to all other voters, whereas Western European far-right voters are less religious and less economically left wing. We do not delve into these differences, as they have been discussed in depth elsewhere (Allen Reference Allen2017; Brils et al. Reference Brils, Muis and Gaidytė2020; Santana et al. Reference Santana, Zagórski and Rama2020).

Focusing primarily on the impact of far-right government participation, we find that the inclusion–moderation hypothesis is empirically supported in both regions: political distrust is a less important determinant of electoral support when far-right parties are in power – the positive OR of the interaction-term means that the negative association between trust and far-right voting is attenuated when far-right parties are in government.

Finally, Models 6a and 6b show the results for two subsamples of countries (WECs and CEECs) in which far-right parties have been both in opposition and in government. This is thus a more ‘controlled’ comparison, but it renders our two samples smaller: the analyses include five WECs and six CEECs. The outcomes do not change our conclusion.

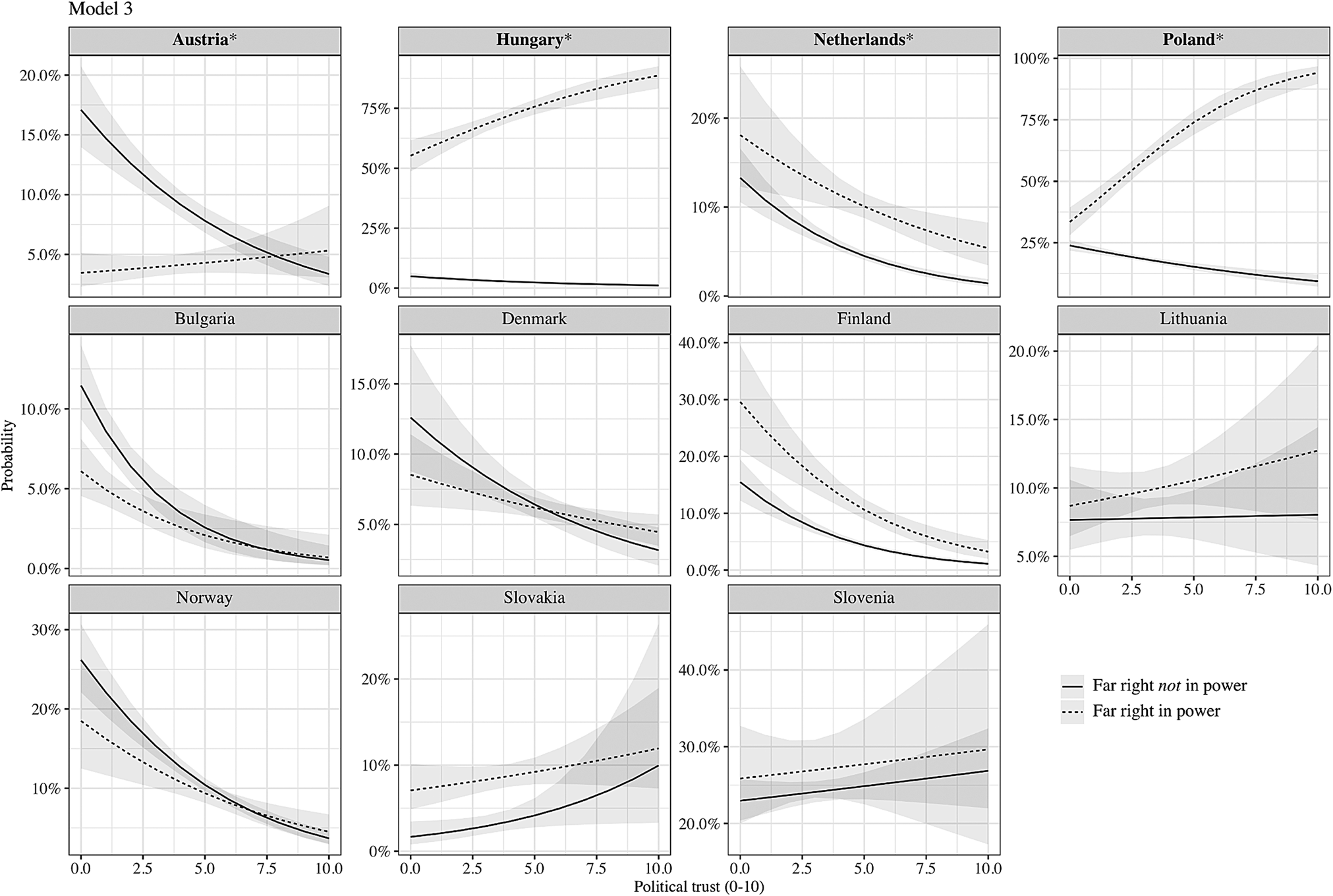

We need to acknowledge a lot of nuances to the overall comparison. There is arguably more heterogeneity within both regions (WEC and CEEC) than across the two regions. Figure 4 depicts the effects of political trust for the set of countries in which far-right parties have been both in opposition and in government. This comparison based on fewer countries is in line with Models 6a and 6b from Table 2; the macro-level variables were omitted from this country-by-country analysis. Additionally, Figure 5 depicts the conditional predicted probabilities of far-right voting for each level of political trust for both conditions in each country – the far right being in power or not (the other independent variables are set to their mean value).

Figure 4. Country-by-Country Analysis: The Effect of Political Trust on the Probability of Far-Right Voting (OR), Broken Down by Far-Right Party Status (in Government vs. in Opposition)

Note: For the control variables, see Model 2 in Table 2.

Figure 5. Effects of Political Trust per Country: Conditional Predicted Probabilities of Far-Right Voting for Far-Right Parties in Power or Not (in Government vs. in Opposition)

Note: Calculations are based on country-by-country regressions of Model 3 (see Table 2). *Country names in bold are statistically significant (p < 0.05, two-tailed).

Overall, these results reveal that far-right parties generally still benefit from political distrust among their voters, even when they are in the government. Yet, there is substantial between-country variation: particularly some countries contribute to the fact that we find a significantly weaker association between far-right voting and political discontent when the far right is in government.

In Western Europe, political trust has a significant negative effect when far-right parties are in opposition, and these effects are smaller when they are in power, although this decrease is in some cases quite small. These results are similar to those of Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos (Reference Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos2020). Interestingly, we see the largest difference in Austria. In this country, far-right voters do not differ from the rest of the electorate (in terms of their average political trust) when the FPÖ or Alliance for the Future of Austria (BZÖ) were members of the government coalition, whereas a large difference is observed when these far-right parties are in opposition (see Figure 4). Figure 5 shows that the share of Austrian far-right voters among ‘low trusters’ (more than 15%) is much higher when the far right is in opposition than when it is in government: when it is in power, less than 5% of the politically least trustful people in Austria vote for the far right. We do not estimate such a large difference for the share of far-right voters among ‘high trusters’: their predicted probability of voting for far-right parties is about 5% and hardly increases when far-right parties share government responsibility.

Focusing on the article's principal contribution, moving beyond Western Europe, we conclude that the picture is more mixed in post-communist Europe. Interestingly, far-right voters in Poland and Hungary are significantly less politically dissatisfied than all other voters when the far right is in power. This resonates with Krause and Wagner (Reference Krause and Wagner2019), who find that PiS and Fidesz voters in 2014 perceived more political efficacy than the rest of the electorate. In contrast, we find that far-right voters in Lithuania, Slovakia and Slovenia are not more politically dissatisfied compared to all other voters (irrespective of the type of government), which might be due to the presence of centrist or left-wing anti-establishment parties in these countries with a similar appeal to politically alienated voters (Engler Reference Engler2020). For instance, the Lithuanian Anti-Corruption Coalition has been summarized as an ‘expression of the protest vote against systemic parties’ (Jastramskis Reference Jastramskis2016).

Finally, it is interesting to note that the influence of ideological voting does not depend on the political status of far-right parties. We conducted additional analyses with interactions of the four variables that represent economic and cultural policy-related preferences, which show that economic grievances and nativism are not weaker predictors of electoral support for far-right parties when these parties are in government. We refer to the Online Appendix for more details on these outcomes.

Hungary and Poland as ‘natural experiments’

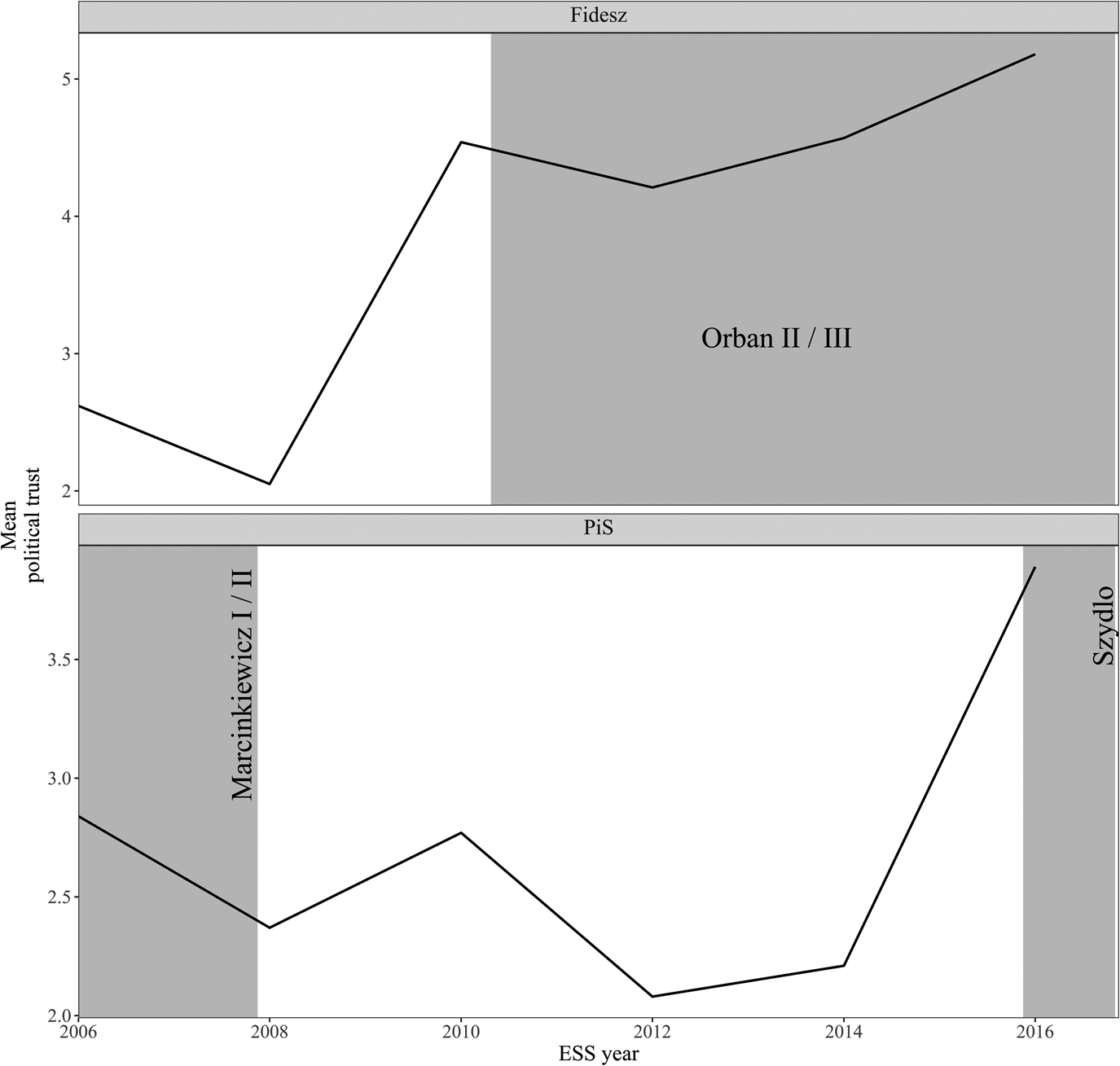

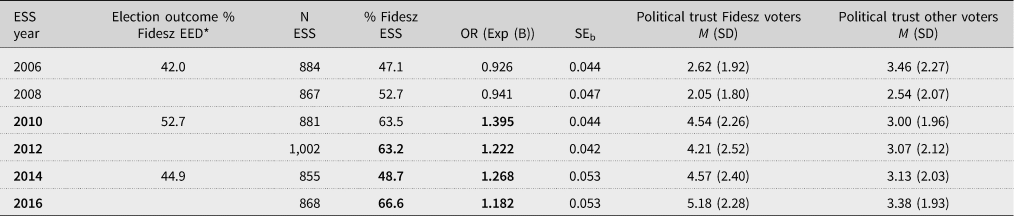

Our analysis fleshed out two interesting cases, namely Hungary and Poland, which can be used as additional but critical stand-alone tests for our inclusion–moderation hypothesis. Over the researched period, Fidesz in Hungary and PiS in Poland transformed from mainstream into far-right parties, and both have also moved from opposition to government. The cases could therefore be considered as ‘natural experiments’: how was political trust of far-right voters affected? Did the negative association between political trust and far-right voting change over time? The results are displayed in Tables 3 and 4 and Figure 6.

Figure 6. Political Trust (Mean) of Fidesz Voters (Hungary) and PiS Voters (Poland), Delineated in the Governmental Periods of the Respective Parties (marked in grey)

Table 3. Means of Political Trust and Effects of Political Trust on Voting for Fidesz (vs. Voting for Other Party or Blank Vote) in Hungary

Notes: *EED: European Election Database, https://o.nsd.no/european_election_database. ESS year in bold: the party is in government. Coefficients in bold: statistically significant (p < 0.05, two-tailed). Control variables included: see Model 2 in Table 2.

Table 4. Means of Political Trust and Effects of Political Trust on Voting for PiS (vs. Voting for Other Party or Blank Vote) in Poland

Notes: *EED: European Election Database, https://o.nsd.no/european_election_database. ESS year in bold: the party is in government. Coefficients in bold: statistically significant (p < 0.05, two-tailed). Control variables included: see Model 2 in Table 2.

Let us consider Hungary first. We see that the ESS data align with the true electoral outcomes if we compare electoral support for Fidesz according to ESS data with actual voting for Fidesz (Table 3). Interestingly, the average political trust level of Fidesz voters increased considerably between 2008 (M = 2.05) and 2010 (M = 4.54), when the party overwhelmingly won the elections (see also Figure 6). Moreover, the association between political trust and far-right voting became positive in 2010 and remains positive thereafter, when Fidesz is radicalized and still in power.

The data suggest that there was a genuine attitudinal change among Fidesz voters – they became more trustful – rather than that this can be attributed to a ‘sorting effect’. The former is more plausible: it seems unlikely that ‘switchers’ have boosted the trust among Fidesz voters, since the average political trust level among the group of other voters has only ranged between about 2.5 and 3.5. This conclusion corresponds with Marton Medgyesi and Zsolt Boda (Reference Medgyesi, Boda and Tóth2019: 352), who observe that the increase in political trust was greater among Hungarians with lower socioeconomic status.

Similarly to Hungary, we see a steep increase in political trust among PiS voters in Poland in 2016, which coincides with the 2015 elections when this party won an absolute majority in parliament. Table 4 and Figure 6 show that since 2006, the political trust of PiS voters first decreased when PiS was in opposition, reaching its lowest score in 2012 (M = 2.08), and then spiked up in 2016 (M = 3.89). Meanwhile, the average political trust of all other voters has remained relatively low over time: this indicates again that attitudes (of PiS supporters) have changed, rather than that a ‘sorting’ process took place. Furthermore, our results show that in the years when PiS formed the government, the association between political trust and far-right voting is significantly positive, while in the years that PiS was in opposition this association is negative.

We can thus conclude that the far right's presence in power in Hungary and Poland considerably boosted the political trust of its voters, and second, it turned political trust into a significant positive predictor of far-right voting. These cases clearly contradict the common generalization that political trust is inversely related to electoral support for the far right.

Finally, an additional benefit of this analysis is the possibility of discriminating between two reasons for the negative association between political trust and the far-right vote: is it their radicalized rhetoric (‘populism’) or their status as political outsiders (‘exclusion’)? Our analysis of Hungary and Poland suggests rather strongly that it is the second explanation: as the far right enters the government, the negative effect of political trust disappears (it even turns positive), while the ‘far-right’ designation change by experts is irrelevant.

Discussion and conclusion

Revisiting the protest-vote explanation for far-right populist voting, this study assessed whether a far-right party's inclusion in government moderates the effect of political trust on far-right voting in Western and Central-Eastern Europe, with a focus on the latter region. Political distrust and dissatisfaction are recurrent notions in research on support for far-right parties (Alvarez et al. Reference Alvarez, Kiewiet and Núñez2018; Hooghe and Dassonneville Reference Hooghe and Dassonneville2018; Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, Van der Brug and De Lange2016). As these parties often portray established elites as unresponsive and corrupt, disaffected voters view far-right parties as potential agents for improving, or at least changing, the functioning of the political system (Bélanger and Aarts Reference Bélanger and Aarts2006). Since the scholarship on far-right voting is heavily Western-oriented, we asked whether the ‘anti-elite hypothesis’ to explain far-right voting travels well to post-communist democracies in Europe (Santana et al. Reference Santana, Zagórski and Rama2020).

Our findings, based on ESS rounds 1–8 (2002–16) and ParlGov data, can be summarized in two conclusions. First, as expected, our results confirm the protest-voting explanation: besides policy-related motivations, political discontent provides an additional explanation for why some Europeans are more inclined to support far-right parties than others.

Second, and more importantly, we conclude that the influence of political distrust is context-dependent: it is strongly related to far-right voting when those parties are in opposition, but this association is significantly weaker when they share government responsibility. Thus, in line with the inclusion–moderation thesis, far-right voters are less disgruntled about politics when their party is in government. Moreover, we likewise found that political distrust is a weaker determinant of far-right voting in CEECs when these parties have more seats in parliament. This confirms the broader literature on electoral behaviour, showing that the provision of a voice in parliamentary representation increases people's trust in politics (Dunn Reference Dunn2012).

Overall, we find that far-right parties generally still benefit from political distrust of their voters, even when they are in the government (cf. Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos Reference Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos2020). There are two notable exceptions to this rule: Hungary and Poland. In both countries, the far right's presence in power considerably boosted its voters' political trust, and it moreover turned political trust into a positive predictor of far-right voting. These two cases clearly contradict the common perception that political trust is negatively associated with electoral support for far-right parties.

Because this is obviously not a ‘classical’ experiment and we do not rely on panel data, we need to be cautious with drawing conclusions about the two underlying causal mechanisms: attitude change and sorting. Empirically, our analysis cannot disentangle them. Relying on cross-sectional data, we cannot observe changes in voting behaviour and/or political trust, but only interpret theoretically meaningful differences as changes.

Nevertheless, our findings suggest that the attitudes of Fidesz and PiS supporters have actually changed, rather than that the parties attracted more trusting voters (i.e. a ‘sorting’ process). Whereas the Hungarian and Polish far-right governments boosted political trust of Fidesz and PiS voters, the average level of political trust among all other voters hardly changed. In contrast to the claim of Harteveld et al. (Reference Harteveld, Kokkonen, Linde and Dahlberg2021) about Western Europe, this has nothing to do with a so-called ‘reservoir of goodwill’ among the mainstream electorate: since trust levels are already very low – particularly in Poland – it seems unlikely, if not impossible, that they could decrease even further. Paradoxically, while Freedom House notes that political leaders in Hungary and Poland ‘have dropped even the pretence of playing by the rules of democracy’ (Csaky Reference Csaky2020: 1), overall political satisfaction has increased in both countries, although, compared to Western Europe, its level still remains rather low.

This article's first contribution to the literature is that our conclusion stresses the importance of the political context. The effect of far-right government inclusion explains why the scholarship sometimes showed mixed and inconclusive results regarding the protest-vote explanation (Alvarez et al. Reference Alvarez, Kiewiet and Núñez2018; Brils et al. Reference Brils, Muis and Gaidytė2020). For instance, based on a panel study in Belgium, Marc Hooghe and Ruth Dassonneville (Reference Hooghe and Dassonneville2018) conclude that there is a ‘spiral of distrust’: those who voted for a protest party (in their case, VB or N-VA) subsequently became more distrusting. Our findings suggest that this conclusion could have limited generalizability as this case lacks the counterfactual alternative of government inclusion – parties were not part of the federal government, but remained in opposition. Likewise, Matthijs Rooduijn et al. (Reference Rooduijn, Van der Brug and De Lange2016) found evidence for the ‘fuelling discontent’ effect of right-wing populist voting. However, PVV voters who were surveyed repeatedly in 2011 and 2012 had not become more distrusting (in fact, although statistically insignificant, the effect is in the opposite direction). Our article clarifies why: in these years the PVV propped up a minority government.

Connecting system-level changes with individual-level political dissatisfaction matches Matt Golder's (Reference Golder2016) recommendation that scholars should pay more attention to the interaction between supply-side and demand-side factors. We concur with Mattia Zulianello (Reference Zulianello2020: 327) that the literature seems not to have sufficiently acknowledged the fact that ‘an increasing number of populist parties are no longer at the margins of party systems; they are instead – as never before –integrated into their national political systems’.

And insofar as scholarship has taken this into account (Cohen Reference Cohen2019; Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld, Kokkonen, Linde and Dahlberg2021; Krause and Wagner Reference Krause and Wagner2019; Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos Reference Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos2020), it has remained strongly Western-oriented. Thus, the article's second, principal contribution is the generalization of this important finding (of both societal and scientific relevance) beyond the Western European party system.

The societal implications are particularly important: if far-right populist actors continue to establish firm footholds in the political landscape, we would expect that the generally higher levels of political dissatisfaction among far-right voters will be reduced in the future (Mauk Reference Mauk2020). Right-wing populist parties may well be conceived as a corrective force, giving voice to and addressing citizen concerns about established politics.

Returning to conceptualization issues, if political distrust indeed taps ‘populist orientations’ (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019), we remarkably conclude that Hungarian and Polish far-right voters are less populist than the rest of the electorate. We can solve this paradox by our earlier argument: we should not primarily label these parties as ‘populist’, as anti-elitism is epiphenomenal to radical right politics; instead, ‘ethno-nationalist’ or ‘nativist’ constitutes the ideological core (Rydgren Reference Rydgren2017). Under the current far-right governments in Hungary and Poland, ‘the idea of a people-oppressing elite is retained but it is re-conceptualized in a way that the executive and parliamentary majority are excluded from the definition’ (Enyedi Reference Enyedi2020: 373). Instead, anti-elite discontent is channelled towards minorities, Europhiles, progressive intellectual elites and the LGBT community. It clearly has a political colour: it does not revolve about ‘who should rule’ but ‘what should be done, what policies should be followed, what decisions should be made’ (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019: 5; emphasis in original).

At least two important questions remain open for further investigation. First, one could further investigate whether and why ideological voting explanations for radical right-wing populist support do not seem to depend on the political status of far-right parties. When far-right parties become more established and powerful actors, the ideological differences between far-right voters and other voters do not seem to decrease.

Another important limitation of our study that can be addressed by follow-up studies is that we did not systematically explore underlying mechanisms at the individual level. Krause and Wagner (Reference Krause and Wagner2019: 11) note that a promising avenue for future research is to disentangle attitude change and compositional effects (i.e. sorting). The notion that voters' political trust may change over time can be extended with questions about how non-voters – who especially form a large group in Central and Eastern Europe – react to changes in the political context. Another important question that is worth exploring further is how opponents of far-right parties (i.e. a subsection of our catch-all category ‘other voters’) react to the political integration of populist far-right parties. We leave these questions open for future studies and debates.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.46.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this study were presented at the 26th IPSA World Congress of Political Science and at a research meeting of the SILC research group of Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. We would like to thank all participants for their helpful much-valued comments and suggestions. We particularly would like to thank Harry Ganzeboom and Aat Liefbroer for their feedback. We also would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers of Government and Opposition, whose feedback has improved this article considerably.