1. Positionality

We are a diverse group of early-career researchers from the Americas and Europe, currently at Global North academic institutions, studying social–ecological and environmental justice. Acknowledging our class privilege as cis-gendered, non-Indigenous researchers, we have accessed education in English, Hungarian, Spanish, German, and Swedish. Our academic formation has connected us with marginalized groups, such as migrants, Indigenous communities, rural workers, and women, in both the Global North and South, enabling us to analyze environmental degradation's root causes while recognizing the social–ecological challenges in the Anthropocene. We believe that to combat climate change and biodiversity loss, the political economy driving environmental degradation must change and that scholars must actively engage in this transformation. We recognize research and academia as politicized arenas that have shaped today's inequalities, necessitating efforts to counter these disparities. Our work aims to redistribute power and address social–ecological inequities, contributing to a just and sustainable path. This paper seeks to further this goal.

2. Introduction

Social–ecological transformation is needed to stay within a safe and just operating space of the biosphere (Folke et al., Reference Folke, Jansson, Rockström, Olsson, Carpenter, Chapin, Crépin, Daily, Danell and Ebbesson2011; Rockström et al., Reference Rockström, Gupta, Qin, Lade, Abrams, Andersen, Armstrong McKay, Bai, Bala, Bunn, Ciobanu, DeClerck, Ebi, Gifford, Gordon, Hasan, Kanie, Lenton, Loriani and Zhang2023; Westley et al., Reference Westley, Olsson, Folke, Homer-Dixon, Vredenburg, Loorbach, Thompson, Nilsson, Lambin and Sendzimir2011). Attaining transformation at the global scale requires a radical systemic change in values, beliefs, social behavior, and governance (Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Galaz and Boonstra2014). Social–ecological transformation research is a growing body of literature studying social transformations to sustain the biosphere's capacity to provide life-support systems for humanity (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Riddell and Vocisano2015, Reference Moore, Hermanus, Drimie, Rose, Mbaligontsi, Musarurwa, Ogutu, Oyowe and Olsson2023). These transformations toward sustainability are understood as a multi-level and multi-phase process (Geels & Schot, Reference Geels and Schot2007), aiming to provide an alternative to currently dominant socially and ecologically unsustainable and destructive pathways (Herrfahrdt-Pähle et al., Reference Herrfahrdt-Pähle, Schlüter, Olsson, Folke, Gelcich and Pahl-Wostl2020; Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Karpouzoglou, Doshi and Frantzeskaki2015). In other words, through social–ecological transformations, complex social–ecological systems can transform from an earlier unsustainable dominant state to a more desirable regime (Folke et al., Reference Folke, Jansson, Rockström, Olsson, Carpenter, Chapin, Crépin, Daily, Danell and Ebbesson2011). Consequently, the study of social–ecological transformations provides a broad understanding of how economic, social, cultural, political, spatial, environmental, knowledge, and(or) other assets of transformative change might unfold toward more sustainable pathways of social–ecological systems (Herrfahrdt-Pähle et al., Reference Herrfahrdt-Pähle, Schlüter, Olsson, Folke, Gelcich and Pahl-Wostl2020; Reyers et al., Reference Reyers, Folke, Moore, Biggs and Galaz2018).

However, social–ecological transformation can have undesirable and unintended consequences, producing winners and losers and thus posing challenges to achieving equity (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Blythe, Cisneros-Montemayor, Singh and Sumaila2019; Herrfahrdt-Pähle et al., Reference Herrfahrdt-Pähle, Schlüter, Olsson, Folke, Gelcich and Pahl-Wostl2020; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Hermanus, Drimie, Rose, Mbaligontsi, Musarurwa, Ogutu, Oyowe and Olsson2023). For example, intentions to shift from fossil fuels to alternative energy sources such as biofuels have led to destructive land-use change and biodiversity loss. Shifting to biofuel alternatives has also been linked to land grabs by transnational corporations, creating new interactions between the state, private companies, and finance that mainly benefit distant, powerful actors in the North and negatively affect local actors in the South (Borras et al., Reference Borras, McMichael and Scoones2010). In addition to the Global North and South locations, unforeseen transformation effects can deepen inequalities across other dimensions such as gender, age, ethnicity, and class. For instance, unintended consequences of economic growth have disproportionately affected Indigenous people and peasants (Martinez-Alier, Reference Martinez-Alier2003; Svarstad et al., Reference Svarstad, Benjaminsen and Overå2019). These actors have simultaneously counteracted environmental interventions by powerful actors such as companies and government agencies in different places (Svarstad et al., Reference Svarstad, Benjaminsen and Overå2019).

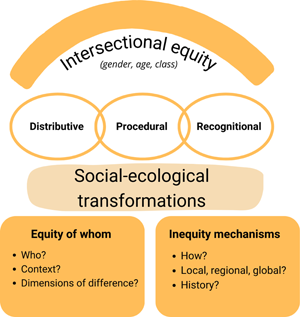

Ensuring equity requires the recognition of transformations toward more sustainable pathways as plural and politicized processes, deeply concerned with questions of transformations of what and for whom (Leach et al., Reference Leach, Reyers, Bai, Brondizio, Cook, Díaz, Espindola, Scobie, Stafford-Smith and Subramanian2018). Environmental justice scholars have proposed conceptualizations of equity to bring attention to possible unintended consequences of sustainable and social–ecological transformations along these pathways. For instance, tri-dimensional equity is comprised of distributive, procedural, and recognition components, and helps to understand better how resources, costs, and benefits are allocated or shared among different groups of people (distributive equity). Also, it allows to make acknowledgments of and respect for identity, values, and associated rights (recognition) and identify which actors can participate and influence decision-making processes in transformation (procedural equity) (Leach et al., Reference Leach, Reyers, Bai, Brondizio, Cook, Díaz, Espindola, Scobie, Stafford-Smith and Subramanian2018; Lenzi et al., Reference Lenzi, Balvanera, Arias-Arévalo, Eser, Guibrunet, Martin, Muraca and Pascual2023; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Coolsaet, Corbera, Dawson, Fraser, Lehman and Rodriguez2016; Schlosberg, Reference Schlosberg2013).

Many scholars have gone a step further, posing questions of equity between whom, recognizing that equity dimensions in pathways toward sustainability are mediated by various aspects of people's identity, such as gender, age, class, and ethnicity (Leach et al., Reference Leach, Reyers, Bai, Brondizio, Cook, Díaz, Espindola, Scobie, Stafford-Smith and Subramanian2018; Lenzi et al., Reference Lenzi, Balvanera, Arias-Arévalo, Eser, Guibrunet, Martin, Muraca and Pascual2023; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Coolsaet, Corbera, Dawson, Fraser, Lehman and Rodriguez2016; Schlosberg, Reference Schlosberg2013). In particular, environmental justice scholars have been questioning why minority communities and other marginalized groups are devalued in the first place (Martinez-Alier, Reference Martinez-Alier2003; Schlosberg, Reference Schlosberg2013). Yet, these approximations of different forms of oppression, such as racism or patriarchy, have generally focused only on one of these various aspects of identity to analyze inequity (Ruiz et al., Reference Ruiz, Luebke, Klein, Moore, Gonzalez, Dressel and Mkandawire-Valhmu2021). Although analyses of tri-dimensional equity have the potential to uncover the political responsibilities of existing inequity (Sikor & Newell, Reference Sikor and Newell2014), studies of multi-dimensional equity that ignore the role of identity are unlikely to explain the mechanisms of inequity effectively. This is because the unequal experiences of environmental and climate disruption are influenced by complex and multi-layered forms of oppression (Di Chiro, Reference Di Chiro and Coolsaet2020).

Intersectionality shifts away from previous theoretical paradigms that analyze a single axis of oppression to develop an awareness of people's unequal experience of the world (Di Chiro, Reference Di Chiro and Coolsaet2020; Ruiz et al., Reference Ruiz, Luebke, Klein, Moore, Gonzalez, Dressel and Mkandawire-Valhmu2021). When used as critical theory, intersectionality provides a comprehensive analysis of why social inequity exists by recognizing that inequity is shaped not only by one but intertwined axes of oppression, for instance, colonialism, racism, and patriarchy (Di Chiro, Reference Di Chiro and Coolsaet2020; Maina-Okori et al., Reference Maina-Okori, Koushik and Wilson2018). Under this vision, uni-dimensional ideas of representation, which only recognize single dimensions of difference such as gender or race, are insufficient to remedy the unequal experience of oppression and discrimination that marginalized groups, such as Black women and Indigenous communities, have of the environment (Di Chiro, Reference Di Chiro and Coolsaet2020).

Our research aims to incorporate intersectionality into tri-dimensional equity analysis to develop a more comprehensive study of people's various experiences of oppression and discrimination in social–ecological transformation. Based on a critical literature review, we propose a way to move beyond previous research using equity analysis in sustainable and just transformations (e.g. Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Blythe, Cisneros-Montemayor, Singh and Sumaila2019; Leach et al., Reference Leach, Reyers, Bai, Brondizio, Cook, Díaz, Espindola, Scobie, Stafford-Smith and Subramanian2018; Schlosberg, Reference Schlosberg2013). We use this literature review because it allows us to critically evaluate how equity has been conceptualized in social–ecological transformation literature. To do so, we first evaluate: (1) How does equity-related social–ecological transformation literature address tri-dimensional equity? Moreover, (2) How does this body of research study equity between whom, meaning how equity is determined and co-produced by different axes of difference such as ethnicity, age, race, gender, nationality, or class? Based on this analysis, we propose an intersectional equity approach to study equity in social–ecological transformation research.

The paper is structured as follows: we first present a brief theoretical background on intersectional equity. Next, we elaborate on our methods for reviewing equity-related social–ecological transformation literature. The results summarize (1) an overview of equity-related studies, (2) our critical reflections on how social–ecological transformation addresses tri-dimensional equity and the differences among various groups, and (3) an intersectional equity approach to research, discussing its potential contributions. Finally, we summarize our core findings in the conclusion.

3. Intersectional equity: applying an intersectionality lens in equity analysis

This section introduces tri-dimensional equity and intersectionality, exploring their significance in the framework of intersectional equity and how they enhance our understanding in a complex social landscape.

3.1 Tri-dimensional equity

Inequity has become one of the twenty-first century's most pressing challenges (Hamann et al., Reference Hamann, Berry, Chaigneau, Curry, Heilmayr, Henriksson, Hentati-Sundberg, Jina, Lindkvist, Lopez-Maldonado, Nieminen, Piaggio, Qiu, Rocha, Schill, Shepon, Tilman, Van Den Bijgaart and Wu2018). Recent work has also focused on pathways to equitable solutions to sustainability challenges, recognizing that the dual goals of equity and sustainability are intertwined (Leach et al., Reference Leach, Reyers, Bai, Brondizio, Cook, Díaz, Espindola, Scobie, Stafford-Smith and Subramanian2018; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Dowing, Sllomane and Sitas2019). Equitable and inequitable outcomes are shaped by the dynamics of social–ecological systems (Hamann et al., Reference Hamann, Berry, Chaigneau, Curry, Heilmayr, Henriksson, Hentati-Sundberg, Jina, Lindkvist, Lopez-Maldonado, Nieminen, Piaggio, Qiu, Rocha, Schill, Shepon, Tilman, Van Den Bijgaart and Wu2018; Leach et al., Reference Leach, Reyers, Bai, Brondizio, Cook, Díaz, Espindola, Scobie, Stafford-Smith and Subramanian2018), and equity includes multiple dimensions (Hamann et al., Reference Hamann, Berry, Chaigneau, Curry, Heilmayr, Henriksson, Hentati-Sundberg, Jina, Lindkvist, Lopez-Maldonado, Nieminen, Piaggio, Qiu, Rocha, Schill, Shepon, Tilman, Van Den Bijgaart and Wu2018). The increasing interest in and influence of the concept of equity has led to significant theoretical developments, including the conceptualization of equity as composed of three mutually interacting and reinforcing dimensions: distributive equity, procedural equity, and recognition (Lenzi et al., Reference Lenzi, Balvanera, Arias-Arévalo, Eser, Guibrunet, Martin, Muraca and Pascual2023; Schlosberg, Reference Schlosberg2013; Sikor & Newell, Reference Sikor and Newell2014). Distributive equity refers to how burdens and benefits are allocated and shared among people (Leach et al., Reference Leach, Reyers, Bai, Brondizio, Cook, Díaz, Espindola, Scobie, Stafford-Smith and Subramanian2018; Schlosberg, Reference Schlosberg2013; Sikor & Newell, Reference Sikor and Newell2014). Benefits and burdens can, for example, be shared equally among actors in a way that contributes to the well-being of the most vulnerable or shared according to the cost incurred (i.e. opportunity cost) (Zafra-Calvo et al., Reference Zafra-Calvo, Pascual, Brockington, Coolsaet, Cortes-Vazquez, Gross-Camp, Palomo and Burgess2017). Procedural equity refers to decisions concerning issues such as who should or should not receive benefits and burdens and the management of conflicts. It includes the right to and the terms of inclusive participation of stakeholders (Leach et al., Reference Leach, Reyers, Bai, Brondizio, Cook, Díaz, Espindola, Scobie, Stafford-Smith and Subramanian2018; Lenzi et al., Reference Lenzi, Balvanera, Arias-Arévalo, Eser, Guibrunet, Martin, Muraca and Pascual2023; Luttrell et al., Reference Luttrell, Loft, Gebara, Kweka, Brockhaus, Angelsen and Sunderlin2013), such as access to justice to solve conflicts and the participation of all relevant stakeholders in decision-making processes (Sikor & Newell, Reference Sikor and Newell2014; Zafra-Calvo et al., Reference Zafra-Calvo, Pascual, Brockington, Coolsaet, Cortes-Vazquez, Gross-Camp, Palomo and Burgess2017). Recognition refers to who can make decisions and the valuation attributed or denied to social and cultural diversity, including respect for people's values, rights, and beliefs (Leach et al., Reference Leach, Reyers, Bai, Brondizio, Cook, Díaz, Espindola, Scobie, Stafford-Smith and Subramanian2018). Thus, recognition refers to acknowledging and respecting different conceptions of values, different identities, and diverse knowledge systems and practices (Lenzi et al., Reference Lenzi, Balvanera, Arias-Arévalo, Eser, Guibrunet, Martin, Muraca and Pascual2023; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Coolsaet, Corbera, Dawson, Fraser, Lehman and Rodriguez2016). It addresses issues linked to domination produced by structural inequity expressed through institutions, language, practices, and symbols at multiple scales, strongly influencing distributive and procedural equity (Boillat et al., Reference Boillat, Martin, Adams, Daniel, Llopis, Zepharovich, Oberlack, Sonderegger, Bottazzi, Corbera, Ifejika Speranza and Pascual2020). Analyzing individuals and social groups can enhance the study of equity dimensions (Leach et al., Reference Leach, Reyers, Bai, Brondizio, Cook, Díaz, Espindola, Scobie, Stafford-Smith and Subramanian2018; Sikor & Newell, Reference Sikor and Newell2014). This approach enables scholars to address equity between different actors. In this study, we propose using intersectionality as a critical theory to examine inequities between individuals and groups across various dimensions of difference.

3.2 Intersectionality

The concept of intersectionality in scholarship originated from the response of Black feminist and women of color feminist movements to the limitations of previous feminist and civil rights movements in addressing interconnected forms of oppression (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Crenshaw and McCall2013; Haschemi Yekani et al., Reference Haschemi Yekani, Nowicka and Roxanne2022; Ruiz et al., Reference Ruiz, Luebke, Klein, Moore, Gonzalez, Dressel and Mkandawire-Valhmu2021; Walby et al., Reference Walby, Armstrong and Strid2012). Kimberlé Crenshaw introduced the concept in 1989 to describe judicial prejudice against Black women in the USA (Crenshaw, Reference Crenshaw1989). Intersectionality has been used to challenge structures that perpetuate inequity (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Crenshaw and McCall2013; Collins, Reference Collins2000; Haschemi Yekani et al., Reference Haschemi Yekani, Nowicka and Roxanne2022; Maina-Okori et al., Reference Maina-Okori, Koushik and Wilson2018). However, it has been criticized for naturalizing and homogenizing people's categorization and its focus on marginalized groups such as Black women, leaving aside the central issue of structural inequity (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Crenshaw and McCall2013; Haschemi Yekani et al., Reference Haschemi Yekani, Nowicka and Roxanne2022; Walby et al., Reference Walby, Armstrong and Strid2012). Politically, intersectionality involves political action and academic practices aimed at achieving social equity (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Crenshaw and McCall2013; Collins, Reference Collins2000). When used as a critical theory, intersectionality refers to the theoretical reflections within the broader praxis of intersectionality to reveal, critique, and challenge power structures (Collins, Reference Collins2019). Consequently, this paper engages with intersectionality as a critical theory to inquire about how power works to produce structural inequity (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Crenshaw and McCall2013; Collins, Reference Collins2019; Haschemi Yekani et al., Reference Haschemi Yekani, Nowicka and Roxanne2022).

3.3 Intersectional equity

We incorporate intersectionality into tri-dimensional equity analysis to examine how power produces distributive, procedural, and recognition-related inequities. As a result, intersectional equity invites scholars to recognize that because all parts of our identity are inseparable and interconnected, peoples’ unequal experience of the world is mediated by axes of difference, such as aspects of sexual orientation, cultural alignment, heritage, gender, socioeconomic status, spirituality, and our connection to nature (Di Chiro, Reference Di Chiro and Coolsaet2020; Maina-Okori et al., Reference Maina-Okori, Koushik and Wilson2018). Thus, under intersectional equity, social inequality is produced by a dominant ideology that imposes norms, roles, expectations, and standards onto different social groups, dividing people into two groups: the privileged, those who have an unearned advantage from the socially constructed ideas of normalcy, and ‘others’, those who are not considered part of the normative ideals and are in a position of less power (Marfelt, Reference Marfelt2016). These dominant ideologies interact to produce multiple axes of oppression that are mutually interconnected and uphold each other to maintain an unequal social order. Thus, oppression occurs when the privileged has social, economic, political, and cultural dominance over one or more ‘others’ (Ruiz et al., Reference Ruiz, Luebke, Klein, Moore, Gonzalez, Dressel and Mkandawire-Valhmu2021). This critical approach drives attention toward the processes of societal interaction that connect multiple axes of oppression, such as racism, patriarchy, and colonialism (Collins, Reference Collins2000; Ruiz et al., Reference Ruiz, Luebke, Klein, Moore, Gonzalez, Dressel and Mkandawire-Valhmu2021).

Consequently, understanding social inequity requires assessing the differences between people from a non-positivist and non-essentialist perspective, recognizing that unequal experiences of the world are produced as an ongoing, context-specific process (Zanoni et al., Reference Zanoni, Janssens, Benschop and Nkomo2010). The existence of both privilege and oppression are situated – that is, what might seem like oppression in one setting can be experienced as a privilege in another (Marfelt, Reference Marfelt2016). Thus, an intersectional equity approach critically reflects about the unequal experience between actors across different axes of difference (e.g. class, occupation, gender, ethnicity, space) and other contextual aspects of status and identity (e.g. disability, language, sexual identity) to unpack the mechanisms which are hindering tri-dimensional equity. Thereby, an intersectional equity approach provides insight into how multiple intertwined axes of oppression intersect and hinder equity in the way (1) benefits and costs; (2) inclusiveness, transparency, access to justice, and accountability in the decision-making process; and (3) the acknowledgment of cultural and knowledge diversity and customary rights are allocated among different actors.

4. Methods

4.1 Data collection

We conducted a critical literature review of social–ecological transformation research. A critical literature review is a method for reviewing a sample literature with guiding questions (Grant & Booth, Reference Grant and Booth2009). In this research, we developed these guiding questions based on our conceptualization of intersectional equity. This allowed us to go beyond a literature summary and critically reflect on the (in)equity of social–ecological transformations. We first identified relevant articles related to the topics of social–ecological transformation (Chaffin et al., Reference Chaffin, Garmestani, Gunderson, Benson, Angeler, Arnold, Cosens, Craig, Ruhl and Allen2016; Moore & Milkoreit, Reference Moore and Milkoreit2020; Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Galaz and Boonstra2014, Reference Olsson, Moore, Westley and McCarthy2017) and tri-dimensional equity (Hamann et al., Reference Hamann, Berry, Chaigneau, Curry, Heilmayr, Henriksson, Hentati-Sundberg, Jina, Lindkvist, Lopez-Maldonado, Nieminen, Piaggio, Qiu, Rocha, Schill, Shepon, Tilman, Van Den Bijgaart and Wu2018; Leach et al., Reference Leach, Reyers, Bai, Brondizio, Cook, Díaz, Espindola, Scobie, Stafford-Smith and Subramanian2018; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Dowing, Sllomane and Sitas2019) through recommendations of scholars who are knowledgeable in the respective fields. These articles were used to establish keywords and terms commonly employed in the literature, such as transformation, transition, justice, equity, equality, social–ecological, socio-ecological, and socio-environmental. On March 14, 2022, we conducted a literature search. As this paper aims to combine intersectionality and tri-dimensional equity analysis, we only focused on scientific peer-reviewed literature while omitting gray literature. Scholarly databases are usually preferable to access peer-reviewed literature (Luederitz et al., Reference Luederitz, Meyer, Abson, Gralla, Lang, Rau and von Wehrden2016). We used Scopus, a multidisciplinary database covering index academic journals from all disciplines, to identify the equity-related social–ecological transformation articles because it provides a more comprehensive overall coverage of peer-reviewed articles compared to other databases (Pranckutė, Reference Pranckutė2021). We used the following search string based on our previous identification of keywords: (TITLE-ABS-KEY (‘transform*’ OR ‘just transition*’) (Topic) AND (‘social-ecologic*’ OR ‘socioecologic*’ OR ‘socio-environment*’ OR ‘socioenvironment*’ OR ‘socio environment*’ OR ‘coupled human and natural system*’ OR ‘coupled human-natural system*’ OR ‘CHANS’) (Abstract) AND (‘Equit*’ OR ‘Equal*’ OR ‘just*’)).

The search revealed 91 publications published between 2012 and 2022, including conceptual, synthesis, and empirical papers. We narrowed our analysis to only empirical papers describing transformation processes for specific case studies, resulting in 37 publications (2013–2022) forming our analysis material. We narrowed our analysis to empirical papers because dimensions of equity and power relations are situated (Collins, Reference Collins2000, Reference Collins2019; Sikor & Newell, Reference Sikor and Newell2014). As a result, it was challenging to address equity issues of what and whom when coding more theoretical papers as the relationships between actors become increasingly conceptual. To critically evaluate each paper, we developed an individual reading protocol and held group discussions, in which the first five co-authors participated regularly. Developing the protocol was an iterative process that occurred over multiple bi-weekly sessions between March and June 2022. We used intersectional equity to guide the reading and the literature coding to evaluate the publications with a comprehensive understanding of equity. We considered the multidimensional and interconnected complexity of multiple drivers causing a lack of equity or impacting equity and oppressions, accumulating in emergent matrices of oppression. The first group discussions informed the outline of the individual reading protocol, where we developed a set of guiding questions to address across the breadth of articles in our review. These guiding questions were formulated to support a critical approach to reading, discussing, and coding the articles in the sample. The critical guiding questions were co-created deductively and inductively. We first created broad categories, dimensions, and assets of analysis based on our previous knowledge of intersectionality, equity, and transformations. We developed and refined the assets and questions of analysis based on the insights from our reading group discussions. Once we established a final version of the protocol, one reader assessed one of the selected articles. Updating the codes for articles that had already been evaluated was necessary if they were assessed using an earlier version of the protocol (Figure 1). The reading group discussions also served to calibrate codes between readers to ensure that everyone in the group was applying similar criteria when describing and scoring assets of analysis.

Figure 1. Visualization of the method as a process of critical literature review.

4.2 Data analysis

The individual reading protocol was employed to critically evaluate the 37 selected articles based on four categories of analysis: (1) overview of the study, (2) transformation, (3) tri-dimensional equity, and (4) intersectionality. Each category was assessed using 26 analytical assets, with four to nine assets assigned to each category. In this context, the categories of analysis address three key aspects: what is being transformed (transformation), the level of equity involved (equity), and the relationships among different groups (intersectionality) within social–ecological systems. The analytical assets represent the components across these three categories that may change in social–ecological transformations. Examples of these components include the economy or political systems (transformation), the inclusiveness or transparency of decision-making processes (equity), and the power dynamics or intersubjective relationships among actors (intersectionality). The dimensions refer to a broader tri-dimensional understanding of the material and moral aspects of equity (Leach et al., Reference Leach, Reyers, Bai, Brondizio, Cook, Díaz, Espindola, Scobie, Stafford-Smith and Subramanian2018) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Hierarchy of categories, dimensions, and assets of analysis used for critically reviewing the 37 equity-related social–ecological transformation studies.

One reader evaluated a selected article using the guiding questions in Table 1 to assess each asset of analysis. To address the overview assets of analysis (type of publication, theoretical background, location, SES, method), each reader provided a brief description answering each question. On the contrary, to assess the transformation, tri-dimensional equity, and intersectionality categories, readers gave a score of ‘2’ in a given asset if the authors substantially addressed a topic, ‘1’ if the topic was implicitly or tangentially addressed, and ‘0’ if the publications did not mention or consider the topic. In other words, articles scored the highest in an asset of analysis (2) when the reader considered the authors of a publication substantially addressed the topic. In contrast, publications received half the score (1) if an asset of transformation was implicitly or tangentially addressed and no points (0) if the asset was not addressed. For the tri-dimensional equity category, we grouped assets of analysis using the three equity dimensions. The reading protocol also emphasized the importance of a critical reflection on the assessment, providing guiding questions. These reflections often informed the reading group discussions.

Table 1. Categories, dimensions, and assets of analysis used for critically reviewing equity-related social–ecological transformation research

After the authors established the final individual reading protocol, group discussions identified broader patterns across the studies. Group discussions were held (bi-)weekly for 8 months, between August and November 2022 and May and September 2023. In these meetings, the readers discussed what was surprising, puzzling, or missing from the publications. We recorded group discussions and took notes to document emerging patterns, insights, and trends, which led to developing an intersectional equity approach to study social–ecological transformations. Once we completed the study assessments and discussions, we evaluated the distribution of scores for each asset and dimension of analysis to determine to what extent the topics were addressed. We also summarized the theoretical background, location, SES, and method to discuss the context in which each study took place by aggregating readers' descriptions for each of these assets of analysis. We aggregated this information for descriptive purposes to better understand the characteristics of the studies as a whole. For a complete description of the reading protocol, codes, and coding exercise, see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24100413.v2.

5. Results

We present results addressing two research questions from the introduction: how equity-related social–ecological transformation literature handles tri-dimensional equity and how equity arises from various axes of difference. We also propose an intersectional equity approach for studying equity in social–ecological transformation research. First, we provide an overview of 37 reviewed articles.

5.1 Overview of reviewed articles

In our sample of 37 articles, we found several theoretical backgrounds applied by transformation scholars: environmental justice (n = 8), governance (n = 7), energy (n = 7), political ecology (n = 5), resilience (n = 5), and agroecology (n = 4). For the highest-scoring articles (i.e. scored 2 across all analysis categories), environmental justice was the primary common topic. Most studies used qualitative methods (n = 35), primarily interviews and workshops, whereas only two employed quantitative methods. Four studies included participatory methods, such as photovoice and participatory mapping. Most articles featured one or more case studies at the country or local level (n = 29), with few (n = 3) analyzing global or supranational levels, and the rest unspecified (n = 5). Case studies spanned five continents, covering diverse SES, including rangelands, mountains, urban areas, coastal communities, and Indigenous lands (Figure 3). No articles described cases from Australia, most of Africa, or the three most populated countries: India, China (one case in Hong Kong), and Indonesia. Among the 30 articles with locations, 12 are from the Global South, 17 from the Global North, and one contains cases from both.

Figure 3. Location of case studies (n = 30). Global, supranational, and studies where location is unspecified are not shown in the map.

In the transformation analysis category, various assets were identified through group discussions: economic, social, cultural, political, spatial, environmental, and knowledge. Economic assets include living standards, employment, income, wealth, and capital. Social assets cover status, rights, justice, and protection systems, whereas cultural assets reflect the ability to practice identities. Political assets relate to influencing decision-making, and spatial assets emphasize values linked to geographies. Environmental assets include access to natural resources and resilience to risks. Knowledge pertains to access and contributions to diverse knowledge systems.

Our analysis indicated that the social (n = 34), spatial (n = 30), and environmental (n = 30) assets are most frequently mentioned, with economic (n = 27) and social (n = 23) assets getting somewhat less attention, whereas environmental (n = 27) and social (n = 23) assets are most substantially and meaningfully addressed (Figure 4). All reviewed articles defined transformation using more than one of the aforementioned assets of transformation. In eight cases, the studies involved assets of transformation that were not described in the coding scheme, defining transformation as being technical, inherently multi-layered, or as a disruptive social practice (e.g. Allen & Apsan Frediani, Reference Allen and Apsan Frediani2013; Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Chase, Frankel-Goldwater, Osborne-Gowey, Risien and Schweizer2017; Olarte-Olarte & Olarte-Olarte, Reference Olarte-Olarte and Olarte-Olarte2019). In using the concept of transformation, some reviewed articles raised a call for a deeper engagement with the meaning of transformation (e.g. Allen & Apsan Frediani, Reference Allen and Apsan Frediani2013; Harper et al., Reference Harper, Salomon, Newell, Waterfall, Brown, Harris and Sumaila2018). As an example of the multiple levels at which transformation may have effects, Harper et al. (Reference Harper, Salomon, Newell, Waterfall, Brown, Harris and Sumaila2018) discuss a fisheries conflict on Canada's Pacific coast. The Indigenous women, as agents of change, led a transformation process that, in the end, was not only about a change in governance but also affected the colonial-enduring patterns in society through the recognition of power, knowledge, and authority.

Figure 4. Scoring of assets of analysis for the categories of transformation, tri-dimensional equity, and intersectionality, where a score of ‘2’ was given if authors substantially addressed a topic; a score of ‘1’ if the topic was implicitly or tangentially addressed; and a score of ‘0’ if the publications did not mention or consider the topic.

5.2 How do studies on social–ecological transformations address tri-dimensional equity?

For the distributive equity dimension, we found the two assets among the most frequently mentioned (allocation of benefits, n = 27; allocation of costs, n = 24) (Figure 4). We found that most (n = 24) of the articles discuss how the benefits and burdens of transformations are distributed among different actors or institutions in terms of distributive equity. For example, Partridge et al. (Reference Partridge, Thomas, Pidgeon and Harthorn2018) discussed burdens in terms of how changes in the UK and US energy systems may have varying effects across and within different groups of society. The allocation of benefits may vary spatially across regions, as shown in a study of Germany's process of divesting from coal and moving toward a greener economy (Weber & Cabras, Reference Weber and Cabras2017). However, articles did not always include the benefits and burdens, and if being discussed, these were not always simultaneously addressed. Out of the reviewed articles, 7 out of 37 did not mention any assets of distributive equity. These seven publications also only tangentially addressed (i.e. scored ‘1’) other aspects of procedural (in)equity and recognition.

Regarding procedural equity, inclusiveness in the decision-making process is the most studied form of procedural (in)equity (Figure 4). Transformation scholars knew that fostering inclusiveness and transparency in decision-making goes beyond creating multi-stakeholder or polycentric, that is, multiple centers of decision-making participatory processes. Besides, authors who substantially address inclusiveness generally recognized the need to make power inequity in decision-making visible by recognizing the domination of influential actors and institutions (e.g. Allen & Apsan Frediani, Reference Allen and Apsan Frediani2013; Barragan-Contreras, Reference Barragan-Contreras2022; Ulloa, Reference Ulloa2021). In these cases, domination was often described as formal, traditional, science-based, top-down, colonial, or Western. For instance, Allen and Apsan Frediani (Reference Allen and Apsan Frediani2013) described the need for a broader discussion about how rights and citizenship are articulated in urban agriculture in Accra, Ghana. According to the authors, missing out on the latter makes practices to correct unequal outcomes reproduce economic cycles of dependency, which in turn hinder economic empowerment. Similarly, Duarte-Abadía and Boelens (Reference Duarte-Abadía and Boelens2019) suggested that the root cause of the displacement of rural communities in the Guadalhorce Valley, Spain, is the implementation of a uniform, top-down irrigation system that guarantees water supply for powerful actors, leading to the abolition of self-organized water governance. This transformation was underpinned by ‘expert and positivistic knowledge implemented through objectifying science’ (Duarte-Abadía & Boelens, Reference Duarte-Abadía and Boelens2019, p. 165).

About two assets of procedural equity, accountability and access to justice, few publications addressed whom to raise concerns and conflict resolution in decision-making toward transformations (Figure 4). Both assets of procedural equity were the least mentioned, with only 9 (accountability) and 11 (access to justice) of the articles considering these forms of (in)equity as relevant in the transformation process. Reflections around procedural (in)equity also led to questioning the universalization of concepts such as justice, development, sustainable consumption, transformation, and transition, drawing attention to the power of language and knowledge (e.g. Ayers et al., Reference Ayers, Kittinger and Vaughan2018; Barragan-Contreras, Reference Barragan-Contreras2022; Lee, Reference Lee2017; Reid et al., Reference Reid, Fernández-Giménez, Wilmer, Pickering, Kassam, Yasin, Porensky, Derner, Nkedianye and Jamsranjav2021). Barragan-Contreras (Reference Barragan-Contreras2022) and Reid et al. (Reference Reid, Fernández-Giménez, Wilmer, Pickering, Kassam, Yasin, Porensky, Derner, Nkedianye and Jamsranjav2021) acknowledged the importance of having a plurality of perspectives to discuss not only what is being transformed and how costs and benefits are distributed but also how different actors understand and envision concepts such as equity and transformation in a particular context. The latter also shows how transformation scholars recognize transformation and equity as situated concepts.

About the dimension of recognition, we found that more than half of the papers recognized cultural diversity and different ways of knowing between actors in the transformation process (cultural diversity, n = 22; knowledge systems, n = 27). Articles that recognized cultural and knowledge diversity intimately linked recognition to discussions about inclusiveness. We identified that papers scoring higher in the assets of cultural and knowledge diversity used different dimensions of difference, such as indigeneity, gender, class, or nationality, among others, to describe diversity, thus linking different imaginaries of the transformation to different ways of knowing and being in the world (e.g. Apgar et al., Reference Apgar, Cohen, Ratner, de Silva, Buisson, Longley, Bastakoti and Mapedza2017; Forget & Bos, Reference Forget and Bos2022; Muñoz-Erickson et al., Reference Muñoz-Erickson, Meerow, Hobbins, Cook, Iwaniec, Berbés-Blázquez, Grimm, Barnett, Cordero and Gim2021). For example, Ulloa (Reference Ulloa2021) argued that the decarbonization of the economy in La Guajira, Colombia, requires a just relational transition that changes current human and human–non-human relationships based on the worldview, livelihoods, and knowledge of the local Wayuu Indigenous people. Recognizing Western and Indigenous worldviews as different, Ulloa (Reference Ulloa2021) challenged the Western idea of justice as universal, showing that a relational ontology underpins justice under an Indigenous perspective.

On the contrary, we noticed that a tangential or poor recognition of diversity makes it difficult for scholars to identify the causes of conflicts and reasoning for mobilizing different practices and resources in their case studies. For instance, a study aiming to describe the transformative potential of the car industry in Austria concluded that the potential for actively politicizing the transformation of the car industry in Austria is limited because ‘mobility practices and decisions are taken for granted’ (Pichler et al., Reference Pichler, Krenmayr, Maneka, Brand, Högelsberger and Wissen2021, p. 7). Although authors recognized class-related power asymmetries as a barrier for more radical transformations, they did not mention potential factors underpinning the class formation process among work councils and trade unions, meaning authors did little to understand who these workers are and how imaginaries of transformation might be determined by factors beyond class such as migration, gender, or language. By presenting workers as homogenous, the authors made it hard to unveil who is behind these imaginaries and why it might be difficult or inconvenient for some workers to engage with radical transformation ideas. Thus, when considering different subjectivities, transformation scholars can address questions such as: What are the individual or collective burdens and benefits of being transformative? What mobilizes different actors to change or transform? Why is it difficult for actors to challenge dominant imaginaries of equity, justice, transformation, or transition?

Finally, when analyzing recognition, we identified that only 12 papers address statutory and customary rights, of which nine substantially address this asset. Of these, five studies focused on coastal areas and four articles on Indigenous lands. Barragan-Contreras (Reference Barragan-Contreras2022), Harper et al. (Reference Harper, Salomon, Newell, Waterfall, Brown, Harris and Sumaila2018), and Ulloa (Reference Ulloa2021) documented the displacement, dispossession, and resistance of Indigenous people to cultural assimilation and market integration. Coastal-related publications (Ayers et al., Reference Ayers, Kittinger and Vaughan2018; Duarte-Abadía & Boelens, Reference Duarte-Abadía and Boelens2019; Harper et al., Reference Harper, Salomon, Newell, Waterfall, Brown, Harris and Sumaila2018) evaluated rights issues linked to the local communities' self-governance of fisheries and irrigation systems.

5.3 How does social–ecological transformation address equity between actors in the transformation process?

Evaluated articles mentioned intersectionality assets in most studies, with power imbalances occurring the most often (n = 33). Our findings also suggest that most transformation scholars know the link between power asymmetries and inequity (power imbalance, n = 28). However, less than half of the publications could substantially describe how power imbalances result in inequity (power and inequity, n = 18) (Figure 4). The latter suggests that despite being aware of inequity, articles generally address the linkage between power asymmetries and inequity superficially without unpacking these mechanisms.

Transformation scholars who unpacked the linkages in more detail could clearly situate their case studies, which helps them better explain how inequity hinders transformation. For instance, Juri et al. (Reference Juri, Zurbriggen, Bosch Gómez and Ortega Pallanez2021) draw the connections between coloniality, modern thinking, and the difficulties of imagining a sustainable future in Latin America. Through their reflections, the authors argued that structural difficulties for many people to meet their basic needs lead to material and epistemological inequities in the region, making it hard for people to re-imagine the future. The authors explained how structural material and epistemological inequity are rooted in colonial ideologies. However, despite the need to change the coloniality of knowledge to attain sustainability, inequity reinforces the material and cultural reproduction of privilege in the region, further reproducing colonial ideologies. This article explains how inequity hinders transformation toward sustainability in Latin America by reflecting on the broader socio-political context of the region.

In addition, we found that 25 of the publications addressed at least one axis of difference, yet only nine scored 2 in the intersubjectivity asset of analysis (Figure 4). The most used factors of difference to describe actors in the transformation process were indigeneity, gender, age, place/space (e.g. Latin American people, people in the Global South), and class. We noticed publications that substantially address intersubjectivity, that is, evaluate multiple axes of difference among actors, explain in more detail the tensions and conflicts between actors. For example, Weber and Cabras (Reference Weber and Cabras2017) used factors such as space, place of residency, and social awareness to understand the socio-environmental conflicts related to an energy transition in Germany. By using several factors of difference to conceptualize conflicts, the article identified the complexity of conflicts around the country's energy transition, providing a detailed overview of the multiplicity of political agendas among actors and institutions. Six of the nine papers scoring high in this intersubjective asset used environmental justice to frame their research.

When reflecting on intersubjectivity at the individual and micro-group levels, we collectively observed that historically marginalized actors generally conduct mobilization of resources and practices such as Indigenous people, local resource users, peasants, workers, women, and youth (e.g. Barragan-Contreras, Reference Barragan-Contreras2022; Boillat & Bottazzi, Reference Boillat and Bottazzi2020; Harper et al., Reference Harper, Salomon, Newell, Waterfall, Brown, Harris and Sumaila2018; Ulloa, Reference Ulloa2021); this is true in cases in the Global South and North. For example, on the Central Coast of British Columbia, Canada, Heiltsuk women led a change in fishery governance through civil disobedience, intergenerational education, mobilization of people and resources, and negotiation with formal authorities, resulting in a co-management process for the herring fishery (Harper et al., Reference Harper, Salomon, Newell, Waterfall, Brown, Harris and Sumaila2018). Although these women have traditional roles as caretakers and leaders in their community, and thus significant influence over the outcome, they also bore great responsibility as ‘mothers, teachers, community and domestic managers, and political leaders in defense of their children, culture, and future generations’ (Harper et al., Reference Harper, Salomon, Newell, Waterfall, Brown, Harris and Sumaila2018, p. 193). Similarly, Trevilla Espinal et al. (Reference Trevilla Espinal, Soto Pinto, Morales and Estrada-Lugo2021), in their interviews with a group of women farmers from across Latin America and the Caribbean, found that recognition of women's work in food systems, including unpaid household work, and the critical role women play in strengthening and maintaining ‘the social fabric’ are crucial components of transforming the agri-food system (Trevilla Espinal et al., Reference Trevilla Espinal, Soto Pinto, Morales and Estrada-Lugo2021). In this context, food system transformation hinges on agroecology as a social movement to redistribute power and resolve inequities and must include feminism.

More than half of the articles addressed the root causes of inequality (inequity mechanisms, n = 23). However, only 13 articles substantially described the reasons and origins of the winners and losers. For instance, when evaluating the article (Weber & Cabras, Reference Weber and Cabras2017), we found that, despite the authors having a good characterization of the socio-environmental conflicts around Germany's energy transition, the article was primarily descriptive and had no clear explanation of the root causes of conflicts. This superficial analysis is surprising since other scholars have well documented the disparities between the West and East of Germany. For example, Wegener and Liebig (Reference Wegener, Liebig, Wegener and Liebig2018) recognized the East and West of Germany as having different ideas of justice and how to improve people's well-being. Another example is the research by Ayers et al. (Reference Ayers, Kittinger and Vaughan2018), who explored the institutional changes in natural resources management in Hawaii over the last 200 years and concluded that, despite the existence of a contemporary co-management regime, rights such as access and withdrawal, exclusion, and alienation are still not fully conferred at the local level. However, the article failed to capture the causes and mechanisms of inequity. It described the historical changes of fisheries governance in Hawaii, yet was missing an exploration of the role of critical historical events such as colonization in establishing co-management areas.

Authors who emphasized the role of history in understanding present inequity unpack the mechanisms of inequity in more depth in their case studies. The latter speaks about the authors' ability to critically reflect on social–ecological transformation and historical constraints on the transformative potential of the process. Our analysis suggests that identifying vital past events that result in social domination and marginalization is essential to critical reflection on social–ecological transformation. A clear example is the research (Allen & Apsan Frediani, Reference Allen and Apsan Frediani2013; Ghosh, Reference Ghosh and Ghosh2018; Trevilla Espinal et al., Reference Trevilla Espinal, Soto Pinto, Morales and Estrada-Lugo2021). These articles critically reflected on the effects of colonization on the cultural domination and dispossession of Indigenous people and other social groups. Thus, we argue that a detailed description of the diversity of actors – that is, substantially addressing intersubjectivity, as done by Ayers et al. (Reference Ayers, Kittinger and Vaughan2018) and Weber and Cabras (Reference Weber and Cabras2017), is not enough to unpack the mechanism of inequity when evaluating social–ecological transformation. On the contrary, inequity is better conceptualized when transformation scholars recognize that domination and oppression are human-made, evaluating when inequity was likely produced.

5.4 An intersectional equity approach to social–ecological transformation research

Using our group discussions, we realized that thinking about the assets of equity and intersectionality allowed us to have an iterative dialogue with the case studies, taking a step back on what was written and asking ourselves what was missing about a case study. Thus, we argue that by using a similar heuristic approach to equity, social–ecological transformation scholars will be better equipped to conceptualize the matrix of oppression where transformation takes place, meaning how inequity hinders actors' agency. The latter speaks to the ability of a transformative process to empower actors and institutions to challenge oppressive social structures. Consequently, we argue that an intersectional equity approach will allow scholars to draw the connections between agents and social structures that (re)produce inequity. We propose intersectional equity as a heuristic approach to understanding the different forms of oppression and privileges actors experience in social–ecological transformations. This section summarizes our interpretative analysis of what an intersectional equity approach to social–ecological transformation implies and how it can contribute to social–ecological transformation.

Our findings suggest that when considering different axes of difference (i.e. equity between whom), transformation scholars can address questions such as: What are the individual or collective burdens and benefits of being transformative? What mobilizes different actors to change or transform? Why is it difficult for actors to challenge dominant imaginaries of equity and transformation? Who defines what the transformation is? How do these definitions influence policy or activism processes? To help scholars unpack such dimensions, we build on previous work that provides probing questions for sustainability decision-making (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Blythe, Cisneros-Montemayor, Singh and Sumaila2019) by considering its application to social–ecological research and by adding a focus on intertwined axes of oppression and inequity, highlighting that further interactions between the various characteristics can unfold, giving rise to emergent and complex, contest-dependent intersectional outcomes. Table 2 presents the critical questions we developed based on our literature review to evaluate social–ecological transformations when using an intersectional equity approach.

Table 2. Critical questions to reflect about empirical studies on social–ecological transformation research

We developed these questions based on the reading codes of our critical literature review and reading discussions.

Transformation scholars should evaluate case studies with diverse interdisciplinary scholars and participants, as we did in our discussions. Engaging with varied perspectives is vital for understanding intersectionality, as researchers experience different inequities influenced by positionality, which affects their privilege and oppression (Ruiz et al., Reference Ruiz, Luebke, Klein, Moore, Gonzalez, Dressel and Mkandawire-Valhmu2021). Thus, based on our history and subjectivity, we are more prone to identify different forms of oppression in different socio-political contexts. During the analysis of the selected publications, we experienced that reflecting on a case study in a non-judgmental space with a diverse group of people helped us go beyond what is self-evident about a case study. In our experience, the group discussions allowed us to improve our individual and collective ability to critically reflect on empirical social–ecological transformation research by challenging the neutrality and passivity of the social context in the transformation processes. As a result, an intersectional equity approach to social–ecological transformation should allow scholars to reflect about their empirical research iteratively.

We also recognize the active role that social structures play when evaluating unequal outcomes. Thus, we suggest that social–ecological transformation scholars think about society as embedded in an intertwined web of axes or a matrix of oppression, as proposed by intersectionality scholars (Collins, Reference Collins2000; Marfelt, Reference Marfelt2016; Ruiz et al., Reference Ruiz, Luebke, Klein, Moore, Gonzalez, Dressel and Mkandawire-Valhmu2021). We believe this perspective could extend and enrich previous views on transformations discussing the role of ‘landscape’ and ‘regimes’, as described by Geels and Schot (Reference Geels and Schot2007) and Herrfahrdt-Pähle et al. (Reference Herrfahrdt-Pähle, Schlüter, Olsson, Folke, Gelcich and Pahl-Wostl2020). Although some scholars have further explored the socio-technical landscape by making the distinctions between socio-technical regimes and landscapes to distinguish the role of the process of social formation from social structures in transformation (Geels & Schot, Reference Geels and Schot2007; Herrfahrdt-Pähle et al., Reference Herrfahrdt-Pähle, Schlüter, Olsson, Folke, Gelcich and Pahl-Wostl2020), such a word choice contributes to naturalizing inequity, making it more challenging to account for its complexity and draw the interactions between agents and social structure and how the latter is (re)produced by the former. Thus, using concepts that more explicitly call for the role of pre-existing inequity in social–ecological transformation, such as ‘social landscape’ or ‘regime of inequity’, will better allow people to reflect on the connections between agency and structure.

Our findings further suggest that intertwined axes of oppression are most likely to be questioned, criticized, and challenged by those actors who experience different axes of oppression in different contexts (e.g. racism, capitalism, patriarchy, coloniality). Such processes of social–ecological transformations are generally mediated and catalyzed by oppressed or marginalized groups to empower themselves or other less powerful actors. However, we also recognize the potential for transformation initiated and enabled by privileged actors. Hence, there is a need to conceptualize further whether and when transformations to foster multidimensional equity can result from privilege and (or) oppression in a given context. Besides, it is expected that by leading the transformation process as marginalized or oppressed (depending on the context), oppressed actors are more likely to encounter violence and coercion (Haugaard, Reference Haugaard2020), which in turn could deepen and widen inequity. However, how oppression increases the costs of transformation is beyond the scope of our review. Thus, we recognize there is a need to understand better how burdens of transformation vary across actors and contexts, depending on whether they experience different forms of oppression or privilege.

Moreover, when using an intersectional equity approach, social–ecological transformations are understood as deliberate changes to counteract structural inequity in social–ecological systems. For this reason, social–ecological transformations generally go beyond discussions of distributive equity to foster procedural equity and recognition. Consequently, under an intersectional equity approach, transformation is rarely the result of social changes to environmental shocks (in the form of adaptation or mitigation efforts) or changes alone, as often explained by climate mitigation and adaptation literature (Lemos & Agrawal, Reference Lemos and Agrawal2006). Although we acknowledge that social–ecological events undoubtedly can lead to changes in social structures (e.g. polycentric governance, co-management of natural resources, and adaptive co-management), we argue that, from an intersectional equity perspective, social–ecological transformation can only result from collective struggle and collective action to challenge the matrix of oppression that reproduces and reinforces social inequity and environmental degradation.

Under this view, environmental change can lead to a social–ecological transformation when actors and institutions are inspired to change perceived inequity as normatively undesirable. However, as imaginaries of what is normative can vary across time and space, intersectional equity recognizes that meanings of equity and other related concepts such as justice are situated. Other environmental justice scholars have also acknowledged the tension between universal claims of justice versus value pluralism (Di Chiro, Reference Di Chiro and Coolsaet2020; Lenzi et al., Reference Lenzi, Balvanera, Arias-Arévalo, Eser, Guibrunet, Martin, Muraca and Pascual2023; Schlosberg, Reference Schlosberg2013; Sikor & Newell, Reference Sikor and Newell2014). Acknowledging the plurality of ideas around equity is also important to interrogate whose imaginaries of equity and justice are implemented given the historical circumstances they inherit and the broader socio-political context (Sikor & Newell, Reference Sikor and Newell2014) where socio-ecological transformation takes place.

As imaginaries of fairness are situated, we argue that social–ecological transformations are evaluated more comprehensively in light of local dynamics and historical changes. However, more than a solely descriptive approach to history is likely required to evaluate the transformative potential of social–ecological transformation. On the contrary, we urge social–ecological scholars to evaluate social–ecological transformations using an intersectional equity approach to critically reflect on the root causes of inequity in their case studies. Among the reviewed studies engaging with root causes and mechanisms of inequity in transformation processes, a common theme was the perception that a transformation to foster equity is generally in tension with pre-existing power structures created during past events such as colonization and civil conflict (Allen & Apsan Frediani, Reference Allen and Apsan Frediani2013; Barragan-Contreras, Reference Barragan-Contreras2022; Harper et al., Reference Harper, Salomon, Newell, Waterfall, Brown, Harris and Sumaila2018; Lee, Reference Lee2017; Ulloa, Reference Ulloa2021). Thus, using an intersectional equity approach, transformation does not happen in a vacuum but rather through institutional, environmental, and economic interactions (Loorbach et al., Reference Loorbach, Frantzeskaki and Avelino2017). A key takeaway from the interdisciplinary conversations is that context and historical perspectives play a significant role in understanding the many different levels at which a transformation process has effects and that these processes are situational, relational, and contingent (Sovacool et al., Reference Sovacool, Kester, Noel and de Rubens2019).

Similarly, we noted the multiple levels and scales of transformation discussed in the articles, including the individual, institutional, and societal levels of analysis at the local, national, and global arenas (Herrfahrdt-Pähle et al., Reference Herrfahrdt-Pähle, Schlüter, Olsson, Folke, Gelcich and Pahl-Wostl2020), and how each one is relevant for transformation toward more sustainable pathways yet has its context which is crucial to considerations of intersectional equity (Wilbanks, Reference Wilbanks and Wilbanks2015). When thinking about transferring ‘what works’ to other contexts, this tension can make it challenging to identify the relevant aspects of individual cases that can be adapted, transferred, or otherwise amplified (Lam et al., Reference Lam, Martín-López, Wiek, Bennett, Frantzeskaki, Horcea-Milcu and Lang2020). Therefore, we also see a need to explicitly incorporate this consideration of scaling (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Riddell and Vocisano2015) in future social–ecological research that addresses (in)equity. We acknowledge that the scope of this review is limited. Thus, we also call for further incorporating intersectional equity to think about social–ecological transformation.

6. Conclusions

We conducted a literature review and discussed the articles in an interdisciplinary group. These discussions helped us understand how social–ecological transformation literature can integrate an intersectional equity approach. Our analysis of the studies reveals the topics explored and their depth, from cobalt supply chain assessment to factors of resilience building. Although the transformations literature is broad, our findings indicate that scholars do not evaluate all transformation assets equally. Social, spatial, and environmental assets are frequently mentioned, with environmental and social assets receiving the most attention. For equity dimensions, benefits, costs, inclusiveness, and knowledge systems are most studied, while accountability is the least mentioned – substantially in three studies and tangentially in six. Intersectionality assets appear in most studies, primarily focusing on power imbalances, whereas intersubjectivity is mentioned in two-thirds of the studies, often only tangentially.

Our findings indicate that to understand the true transformative potential of social–ecological transformations, there is a need to conceptualize the mechanisms of inequity and axes of difference better in social–ecological transformation research. Based on our results, we propose using intersectional equity as a heuristic approach to social–ecological transformations to allow social–ecological transformation scholars to understand better how actors involved in the transformation process experience oppression and privilege. To foster this critical way of thinking, we develop several critical questions and encourage social–ecological scholars to evaluate this set of questions iteratively together with an interdisciplinary group of scholars.

Recognizing that transformation is embedded in axes of oppression, an intersectional equity approach better connects agency and structure. We urge social–ecological scholars to use concepts such as ‘social landscape’ or ‘regime of inequity’ when examining where social–ecological transformation occurs. An intersectional equity approach considers transformations as deliberate changes to counter structural inequity in social–ecological systems. Our findings indicate that marginalized groups generally mediate this transformation, but further conceptualization is needed on how privilege or oppression affects these changes, particularly since oppression increases the costs of transformation. We encourage scholars to further study these aspects using an intersectional equity approach.

Using an intersectional equity approach to social–ecological transformations also requires scholars to evaluate transformation in light of local dynamics and historical changes. Consequently, an intersectional equity approach recognizes that transformation to foster equity is generally in tension with preexisting axes of oppression such as colonization and patriarchy. As social–ecological transformations are situated, it is difficult to identify the relevant aspects of individual cases that can be adapted, transferred, or otherwise amplified. Thus, we also need to incorporate this consideration of scaling when studying social–ecological transformations explicitly.

Data availability

Supplementary data, reading protocol, codes, and coding exercise can be accessed from: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24100413.v2.

Acknowledgments

We thank all researchers involved in our reading group's discussions and exercises over the years. Special gratitude goes to Diana Luna and Rodrigo Martínez Peña for their contributions to the study design. Thanks also to Uno Svedin for his insights that helped shape this paper. The lead author dedicates this work to PJ, deeply grateful for his support and guidance throughout the process, JG.

Author contributions

P. A. S. G.: supervision and coordination of the research. P. A. S. G., K. J., and K. E. P.: lead the conceptualization and methodology. P. A. S. G., K. J., K. E. P., H. E., and M. S.: formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing of the original draft, and review and editing. L. L. final review and editing.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council Formas through the project ‘Networks of Financial Rupture – how cascading changes in the climate and ecosystems could impact on the financial sector’ (2020-00198, 2020); Biodiversa Project ‘Environmental Policy Instruments across Commodity Chains’ (EPICC, Project Number BiodivClim-641); the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation (MMW 2017.0137); the Swedish Research Council Formas (project 2022-00674); the NordForsk Project ‘Green forests policies: a comparative assessment of outcomes and trade-offs across Fenno-Scandinavia’ (project 103443) and the Kamprad Family Foundation (project 31002095); the FUTURES4Fish project which is funded by the Research Council of Norway (grant 325814).

Competing interests

None.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools

During the final review of this work, the authors used AI Grammarly, Inc. to check grammar and spelling and improve portions of the text. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the publication's content.