Introduction

Armed conflict in Syria began in 2011, resulting in massive forced displacement of the Syrian population. As of May 2021, there were 666 692 registered Syrian refugees residing in Jordan (UNHCR, 2021), a number that has been relatively stable since 2014 as the need far exceeds the rate of resettlement (UNHCR, 2021).

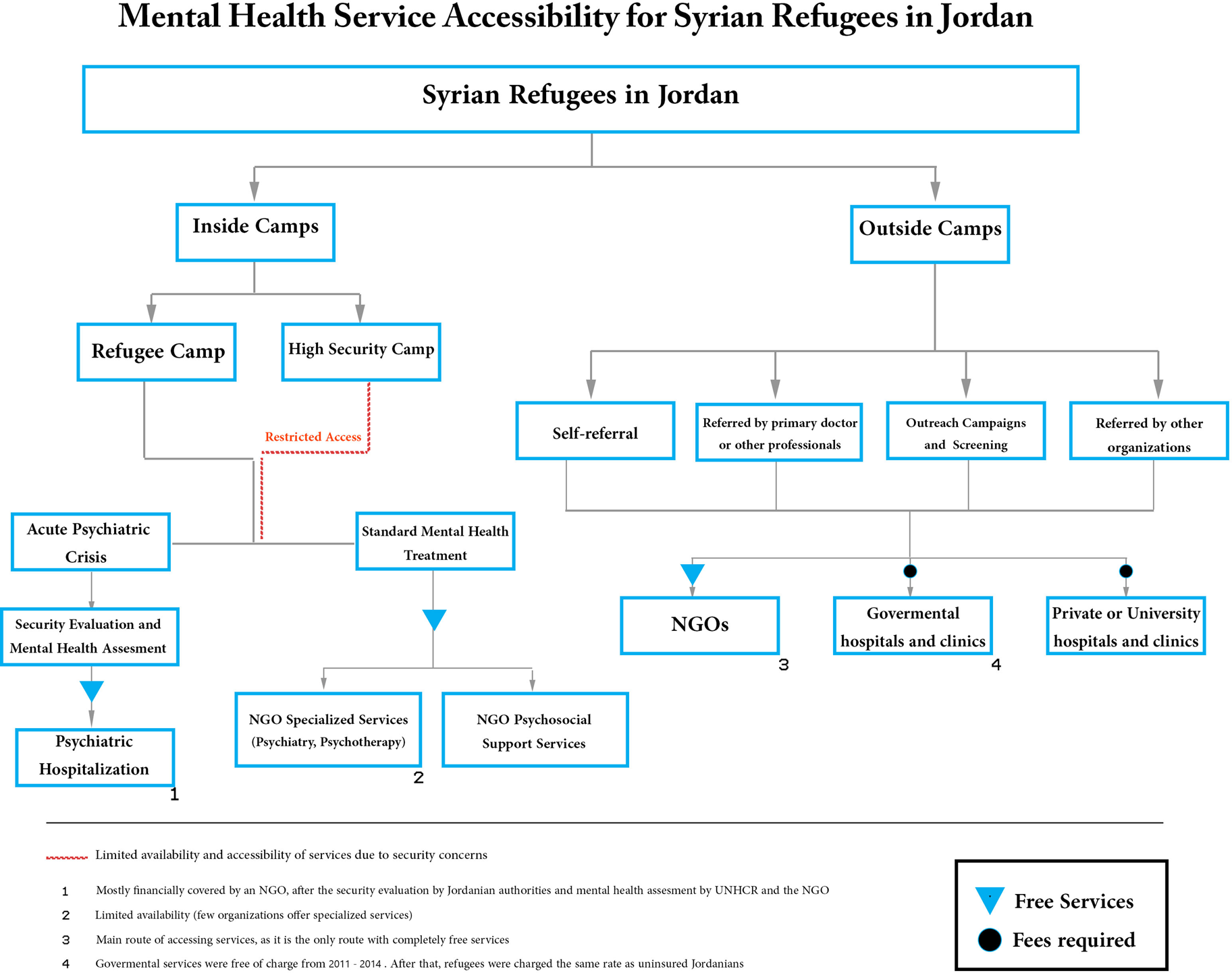

The mental health burden of refugees worldwide has been well documented (Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Njoku and Priebe2015), with Syrian refugees commonly experiencing trauma from violence, the destruction of their homes and livelihood, loss of loved ones to death or separation, and extended periods in refugee camps. Syrian refugees in Jordan access mental health services via three distinct pathways: direct care at a mental health clinic, referral to specialty care by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) or primary health professionals, or field-based outreach teams (Fig. 1. Within camps, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in partnership with foreign and domestic governments and NGOs provide shelter, food, education, and some healthcare services (Bloch and McKay, Reference Bloch and McKay2017).

Fig. 1. Utilizing clinician input to improve refugee mental health.

There are distinctions between services available inside and outside camps, notable as approximately 80% of Syrian refugees in Jordan reside in urban areas, while the remaining live in refugee camps (UNHCR, 2021). Those outside of camps face many difficulties accessing healthcare services, with some studies finding 58–79% of urban refugees unable to access physical or mental health care (UNHCR, 2015; Ay et al., Reference Ay, González and Delgado2016), despite UNHCR registration allowing Syrian refugees to access some services for free or at a subsidized cost (Akik et al., Reference Akik, Ghattas, Mesmar, Rabkin, El-Sadr and Fouad2019).

Numerous prior studies have described barriers to mental health treatment for Syrian refugees in receiving countries, including financial limitations, stigmatization, distrust in healthcare systems, poor accessibility of services, misdiagnosis or lack of screening for mental health symptoms in primary settings, shortage of mental health professionals, communication and language barriers, and legal and immigration issues (Table 1). Although these general barriers to refugee mental health services have been well-documented, there has been minimal investigation of their occurrences in Jordan, despite Jordan's key role in regional stability, brokering foreign humanitarian aid, and hosting refugees. Through numerous local and foreign stakeholders, a new mental health system for Syrian refugees has developed in Jordan, with most clinical services administered through NGOs (IMC, 2017). In this study, we seek to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of this system and investigate how the current Jordanian model addresses these barriers (Table 1).

Table 1. Barriers to mental health service for Syrian refugees in host countries

Methods

Design

An ethnographic approach was chosen to best capture the complex dynamics in which refugee health professionals practice. This method emphasizes how people understand their environment, and is ideal for acquiring a narrative account of a specific setting against a theoretical backdrop, such as the wide-scale changes of globalization and migration (Allard and Anderson, Reference Allard, Anderson and Kempf-Leonard2005).

Interview structure and the interviewing process

A semi-structured format was used, with initial structured questions covering multiple thematic sections: demographic information, clinical experience with refugee mental health, the environment of their system of care, organizational dynamics, and barriers to treatment. The unstructured portion of the interview allowed participants to expand on the initial topics or identify further areas of importance. Questions were formulated from literature review of barriers to care (summarized in Table 1) and pilot interviews were conducted to determine relevance and refine question structure. All participants were interviewed individually between November 2019 and March 2020. Interviews were conducted in Arabic, and interview length ranged between 60 and 123 min (mean = 78 min). All interviews, transcription, and translation for analysis were completed by two of the study authors in tandem (M.A. and M.A.A), both fluent in English and Arabic and having multiple years of Arabic-English translation experience for scientific and popular media publications.

Survey demographics

The interview sample included 20 participants who reside in Jordan and provide psychiatric or psychosocial services to Syrian refugees. The sample included representation from different cities throughout Jordan, as well as professionals in various settings, including inside and outside refugee camps. Professional credentials of participants included psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors, social workers, mental health case managers, and psychosocial program officers and managers. All worked for local or international NGOs. (Appendix Table 1)

Data analysis

Analysis of interview transcriptions proceeded through thematic clustering and coding. Themes included those previously mentioned in the literature, as well as novel themes not previously identified, and were sorted into system barriers and strengths. All coding was done by the authors in tandem to ensure reliability.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this work was granted by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan. Study participation was voluntary with no compensation provided, and all participants provided informed consent prior to study enrollment.

Results

Barriers

Financial barriers in the Jordanian context

Consistent with prior studies, financial challenges were identified as the most significant barrier to refugee services in Jordan. Clinicians reported service restrictions due to funding and lack of personnel and supplies. Medication shortages were a particular bottleneck, leading to prescriptions for less-preferred medication options or unavailability of psychotropics altogether.

In addition to organizational financial limitations, the financial hardship of refugee patients was also a significant limiting factor to accessing care. Clinicians reported that participation in treatment was often interrupted due to refugee patients having difficulty accessing, and thus prioritizing, basic needs. An additional distinct financial challenge for refugees residing outside of camps was cost and availability of transportation to treatment centers.

Burnout and shortages of qualified mental health professionals

Delays in treatment, including evidence-based psychotherapeutic interventions and psychotropic medication also arose from a shortage of mental health clinicians, including psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and counselors. Recommendations for improvement included increasing access to training for highly utilized trauma therapy modalities. Increasing rates of burnout among colleagues was also identified as an important factor to address the shortage of clinicians. Some clinicians became emotional when discussing these topics, highlighting the need for further organizational support.

Systemic and organizational barriers

Numerous organizational issues were identified that impacted treatment, leading to adverse outcomes, clinician burnout, and poor project sustainability. Lack of organizational foresight and sustainability of projects and services was felt to pose challenges to long-term change. Disruptions in continuity or ability to access care were some of the reported consequences.

Interviewees reported that organizational focus on pre-conceived target metrics limited clinician effectiveness. These metrics often prioritized high patient volume over quality of services, and were inflexible regarding number of sessions or the patient's condition or severity. Some respondents noted programs' problematic reliance on these metrics to ensure continued financial support.

All surveyed professionals commented on the inefficiency of communication and coordination between organizations, exemplified by no system for sharing records between organizations, or for screening, reporting, and documenting services. This led to suboptimal outcomes, service delays, duplication of services, unreliable referral processes, and lack of accountability. Some commented that UNHCR had begun to create a system for documentation and coordination, but it was not yet operational. Surveyed professionals uniformly advocated for better reporting, oversight, and follow up mechanisms.

The above organizational processes promoted burnout among clinicians, compounded by reducing time or availability of resilience-building practices. Surveyed professionals uniformly recommended increased attention and organizational commitment to policies and practices responsive to the needs and input of both patients and clinicians.

Stigma

Respondents reported that stigma remains a major barrier to mental health treatment for refugees in Jordan, presenting as the stigmatization of individuals by society, and at times, the patient's own stigma toward mental health treatment. Self-stigma was described as most problematic at the beginning of the therapeutic process and lessening with sessions and time. Comparatively, social stigma was considered to be a continuing problem, and respondents described various strategies designed to help overcome it, including educational campaigns, normalization and increased visibility of services, physically co-locating mental health services with other medical services, and avoiding stigmatizing language in naming.

Hiring refugees as peer support professionals, community liaisons, or as mental health clinicians, was described as a particularly effective approach to reducing stigma and improving access. This strategy aligns with prior research findings and recommendations for using local strengths and resources to develop grassroots approaches for population health (Saraceno et al., Reference Saraceno, van Ommeren, Batniji, Cohen, Gureje, Mahoney, Sridhar and Underhill2007).

Awareness, education, and screening

Poor awareness of available mental health services was common and particularly notable for refugees residing outside camps and in rural areas. Absence of screening and misdiagnosis of psychiatric symptoms in primary settings was also identified as problematic, with reported repeating patterns of worsened case severity after delayed mental health care. Respondents uniformly commented on the importance of implementing screening protocols and improving education for non-mental-health professionals to better recognize mental health symptoms and refer patients when necessary. Notably, some participants were not familiar with the concept of screening, but were in favor of it once an explanation was provided.

Limited accessibility in high-security camps

A small number of high-security camps have been implemented by the Jordanian government due to fears of security threats. Currently, approximately 20 000 Syrian refugees are housed in high-security camp settings (New York Post, 2018; PBS News, 2020). Mobility both for NGOs and refugees is highly restricted in these settings, greatly limiting access to all mental health services.

Strengths

Supportive political and societal response

Clinicians repeatedly commended the effectiveness of the Jordanian government, backed by popular support, in responding to the refugee crisis, specifically for its facilitation and cooperation with NGOs to administer refugee services. Interviewees also described Jordanian societal perceptions of refugees as neighbors, rather than intruders, highlighting the shared historic, cultural, and religious values of the region. Nearly all clinicians reported that historic ties between Jordan and Syria, particularly in culture and language, promoted integration of refugees in mental health programs, and Jordanian society as a whole.

Organizational open-door policies

Offering services to all refugees was highlighted as an effective strategy in Jordan. Many interviewees reported that organizational policies offering services to refugees regardless of circumstances, legal status, or socioeconomic level, allowed them to practice in accordance with their personal and professional ethics. Furthermore, responses indicated lack of documentation was uncommon, and when it did occur, did not pose a barrier to provision of services.

Effects on the Jordanian healthcare infrastructure

This newly developing system of mental health services for refugees was reported to have regionally advanced the field of mental health and brought new economic and educational opportunities for Jordanian students and professionals. Many described personally learning new skills and finding more career advancement opportunities. This new system has also increased the breadth and availability of services offered to Jordanian citizens, as many NGOs have an external or internal mandate to concurrently provide services to Jordanians.

Discussion

The Jordanian response to the Syrian crisis has allowed for development of a new system of mental healthcare for refugees. In collaboration with the UNHCR and numerous NGOs, a wide spectrum of mental services are offered and continue to grow.

Significant barriers remain to improving accessibility of mental health services for Syrian refugees in Jordan, including financial limitations, transportation difficulties, clinician shortages and burnout, inflexible organizational policies, treatment stigma, limited or absent screening protocols, and security restrictions in high-security settings.

A positive sociopolitical response by Jordanian leadership, organizational open-door policies, and contributions to Jordan's healthcare infrastructure were described as major advantages of the Jordanian model.

Clinician input provides an effective mechanism to understand and improve this system (Table 2). Addressing these barriers and capitalizing on system strengths may improve access and outcomes for refugee patients in Jordan and other middle or low income settings worldwide.

Table 2. Clinician recommendations in Jordan

Study limitations and future directions

Some clinicians reported siloing or partitioning of services and had difficulty commenting on larger systemic factors, thus our results may be limited by the clinical focus of study participants. These findings would be strengthened by input from patients and non-clinician stakeholders, including government officials and NGO administrators. Further quantitative investigation may also strengthen these findings and allow for additional analysis across multiple settings. The humanitarian crisis in Syria began in 2011 and continues to evolve—and with it changes the needs of displaced individuals. Continuous appraisal of this developing healthcare system should be undertaken.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2021.36.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dina Aqrabawi, Alaa Shehadeh, Rand Al-Soleiti and Dr. Ala'a Al-Froukh for their continued help and support through the time of this project. We are also indebted to all the interview participants who graciously shared their time and expertise.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

Drs. Rafla-Yuan, Al-Soleiti, and Nashwan have no conflicts of interest to disclose, financial or otherwise. Mr. Abu Adi is employed by CIVIC<www.civic.co>, an international aid NGO with operations in Jordan. Mr. Abu Adi and CIVIC are not involved in healthcare services and Mr. Abu Adi did not receive any incentives to participate in this research work, financial or otherwise.