Introduction

According to the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019, among adolescents and young adults (aged 10–24 years), alcohol-attributable burden is second highest among all risk factors contributing to disability-adjusted life years in this age group (GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators, 2020). The exposure of the adolescent brain to alcohol is shown to result in various cognitive and functional deficits related to verbal learning, attention, and visuospatial and memory tasks, and behavioural inefficiencies such as disinhibition and elevated risk-taking (Spear, Reference Spear2018). Alcohol consumption in adolescents results in a range of adverse outcomes across several domains and includes road traffic accidents and other non-intentional injuries, violence, mental health problems, intentional self-harm and suicide, HIV and other infectious diseases, poor school performance and drop-out, and poor employment opportunities (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Patton, Stockings, Weier, Lynskey, Morley and Degenhardt2016).

Adolescence is a critical period in which exposure to adversities such as poverty, family conflict and negative life experiences (e.g. violence) can have long-term emotional and socio-economic consequences for adolescents, their families and communities (Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, Scott and Davies1999; Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, McCRONE, Fombonne, Beecham and Wostear2002). Substance use, including alcohol, is typically established during adolescence and this period is peak risk for onset and intensification of substance use behaviours that pose risks for short- and long-term health (Anthony and Petronis, Reference Anthony and Petronis1995; DeWit et al., Reference DeWit, Adlaf, Offord and Ogborne2000; Hallfors et al., Reference Hallfors, Waller, Bauer, Ford and Halpern2005; Schmid et al., Reference Schmid, Hohm, Blomeyer, Zimmermann, Schmidt, Esser and Laucht2007; Hadland and Harris, Reference Hadland and Harris2014). As such, early initiation of alcohol use among adolescents can provide a useful indication of the potential future burden among adults including increased risk for academic failure, mental health problems, antisocial behaviour, physical illness, risky sexual behaviours, sexually transmitted diseases, early-onset dementia and the development of alcohol use disorders (AUDs) (Hingson et al., Reference Hingson, Heeren and Winter2006; King and Chassin, Reference King and Chassin2007; Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Goldstein, Patricia Chou, June Ruan and Grant2008; Nordström et al., Reference Nordström, Nordström, Eriksson, Wahlund and Gustafson2013).

India continues to develop rapidly, and accounts for most of the increase in alcohol consumption per capita for WHO's South-East Asia region (World Health Organization, 2018). Although India has a relatively high abstinence rate, many people who do drink are either risky drinkers or have AUDs (Benegal, Reference Benegal2005; Rehm et al., Reference Rehm, Mathers, Popova, Thavorncharoensap, Teerawattananon and Patra2009). Finally, the existing policies in India have failed to reduce the harm from alcohol because the implementation of alcohol control efforts is fragmented, lacks consensus, is influenced by political considerations, and is driven by narrow economic and not health concerns (Gururaj et al., Reference Gururaj, Gautham and Arvind2021).

India has the largest population of adolescents globally (253 million people aged 10–19 years), constituting 21% of the population (Government of India, 2011; Boumphrey, Reference Boumphrey2012). Additionally, adolescents as young as 13–15 years of age have started consuming alcohol in India (Gururaj et al., Reference Gururaj, Varghese, Benegal, Rao, Pathak, Singh and Singh2016). Despite this growing public health problem, the official policy response in India remains primarily focused on AUDs, particularly alcohol dependence in adults, with an absolute disregard for the potential of prevention programmes. One potential reason for this is the limited understanding of the onset and progression of alcohol use and AUDs amongst adolescents in India. The aim of this paper is to bridge that knowledge gap by synthesising the evidence about the prevalence and correlates of alcohol use and AUDs in adolescents from India.

The specific objectives are to examine the following in adolescents from India: (a) prevalence of current and lifetime use of alcohol, (b) prevalence of current AUDs, (c) patterns (e.g. frequency, quantity) of alcohol use, (d) sociodemographic, social and clinical correlates of alcohol use and AUDs, and (e) explanatory models of and attitudes towards alcohol use and AUDs, e.g. perceptions of the problem and its causes. This paper synthesises the evidence about alcohol and AUDs using data from a comprehensive review that we conducted of any substance use and substance use disorders amongst adolescents in India.

Methods

Design

Systematic review. The review protocol was registered prospectively on Prospero (registration ID CRD 42017080344).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

There were no limits placed on the year of publication of the paper, gender of the participants and study settings in India. We only included English language publications as academic literature from India is predominantly published in such publications. Adolescents were defined as anyone between 10 and 24 years of age (Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Azzopardi, Wickremarathne and Patton2018). Studies reporting alcohol use and/or AUDs in a wider age range (including 10–24 years) were included only if data were separately presented for the 10–24-year age group. We included observational studies (surveys, case-control studies, cohort studies), qualitative studies and intervention studies (only if baseline prevalence data were presented). We included studies which examined alcohol use and AUDs defined as per the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)/Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)/clinical criteria or using a standardised screening or diagnostic tool.

Data

We searched the following databases: PsycARTICLES, PsycInfo, Embase, Global Health, CINAHL, Medline and Indmed. The search strategy was organised under the following concepts: substance (e.g. alcohol, drug), misuse/use disorder (e.g. addiction, intoxication), young people (e.g. adolescent, child) and India (e.g. India, names of individual Indian states). The detailed search strategy is listed in Appendix A.

Two reviewers (DG and KW) independently inspected the titles and abstracts of studies identified through the database search. Any conflicts about eligibility between the two reviewers were resolved by AN. If the title and abstract did not offer enough information, the full paper was retrieved to ascertain whether it was eligible for inclusion. Screening of full texts was done by AN, AG and DG; and any conflicts about eligibility were resolved by UB. Screening of the results of the search was done using Covidence (https://www.covidence.org/), an online screening and data extraction tool.

AN searched the following resources to identify relevant grey literature: Open Grey, OAlster, Google, ProQuest, official English language websites of the World Health Organization and World Bank, English language websites of ministries of each state and union territory within India responsible for substance misuse as well as the official websites of the Indian Narcotics Control Bureau and Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment.

Any grey literature with relevant data published by a recognised non-governmental organisation, state, national or international organisation was included. Studies were included based on the robustness of study design and quality of data. If there were multiple editions of any published piece of grey literature, only the latest published edition of that report was included. Once retrieved, their titles, content pages and summaries were read by AN and if deemed eligible they were added to a list of potentially eligible reports. If the grey literature's summary, content and title did not include enough information, then the full text was examined by AN to determine eligibility for inclusion.

Finally, experts in the field of substance use disorders in India were contacted to explore if they could identify any further useful sources of information and were invited to submit unpublished data and unreported outcomes for possible inclusion into the review. Reference lists of selected studies, grey literature and relevant reviews were inspected for additional potential studies.

A formal data extraction worksheet was designed to extract data relevant to the study aims. The following data were extracted: centre (e.g. name of city), sampling technique, sample (e.g. general population), sample size, age(s), tool used to measure alcohol use and/or AUD, definitions of alcohol use and AUD, prevalence of alcohol use and/or AUD, age of initiation, type of alcohol, quantity and frequency of alcohol use, attitudes towards alcohol use, effect of alcohol on health, social, educational and other domains, and risk factors/correlates of alcohol use and or AUD. Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Shamseer, Clarke, Ghersi, Liberati and Petticrew2015), a record was made of the number of papers retrieved, the number of papers excluded and the reasons for their exclusion. AT independently performed data extraction, AG checked the data extraction, and AN arbitrated any unresolved issues. The quality of reporting of included studies was examined using the STROBE Statement – checklist of items that should be included in reports of observational studies (Von Elm et al., Reference Von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke2007).

A descriptive analysis of the data was conducted, and the results are mainly reported in a narrative format focusing on each of the objectives described above (Popay et al., Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai, Rodgers and Duffy2006).

Results

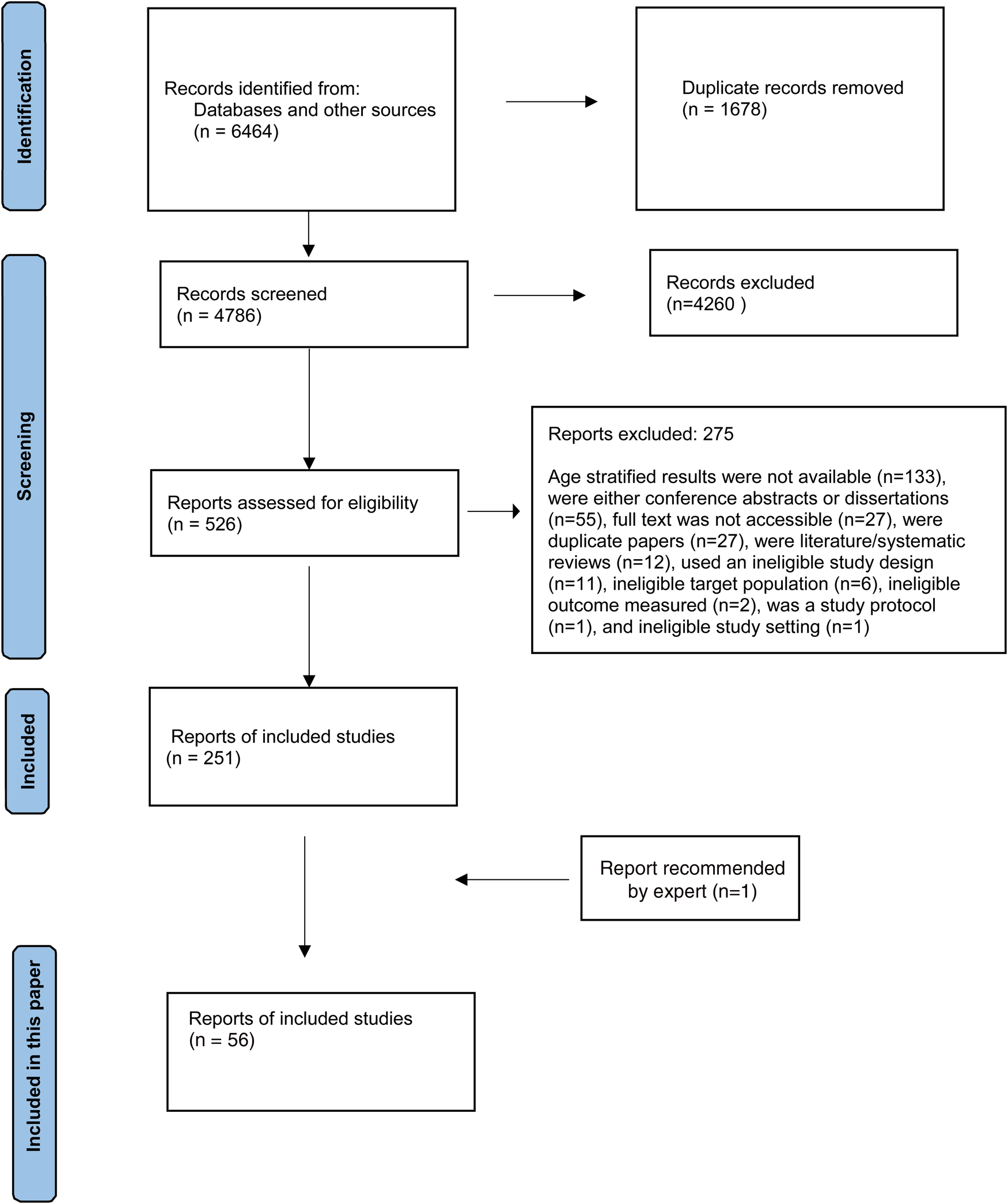

In total, 6464 references were identified through the search strategies described above. Overall, 251 records were eligible for the wider review, of which 55 were about alcohol use and have been reported in this paper (Fig. 1). Additionally, one report of magnitude of substance use in India which was recommended by an expert was also included (Ambekar et al., Reference Ambekar, Agrawal, Rao, Mishra, Khandelwal and Chadda2019).

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

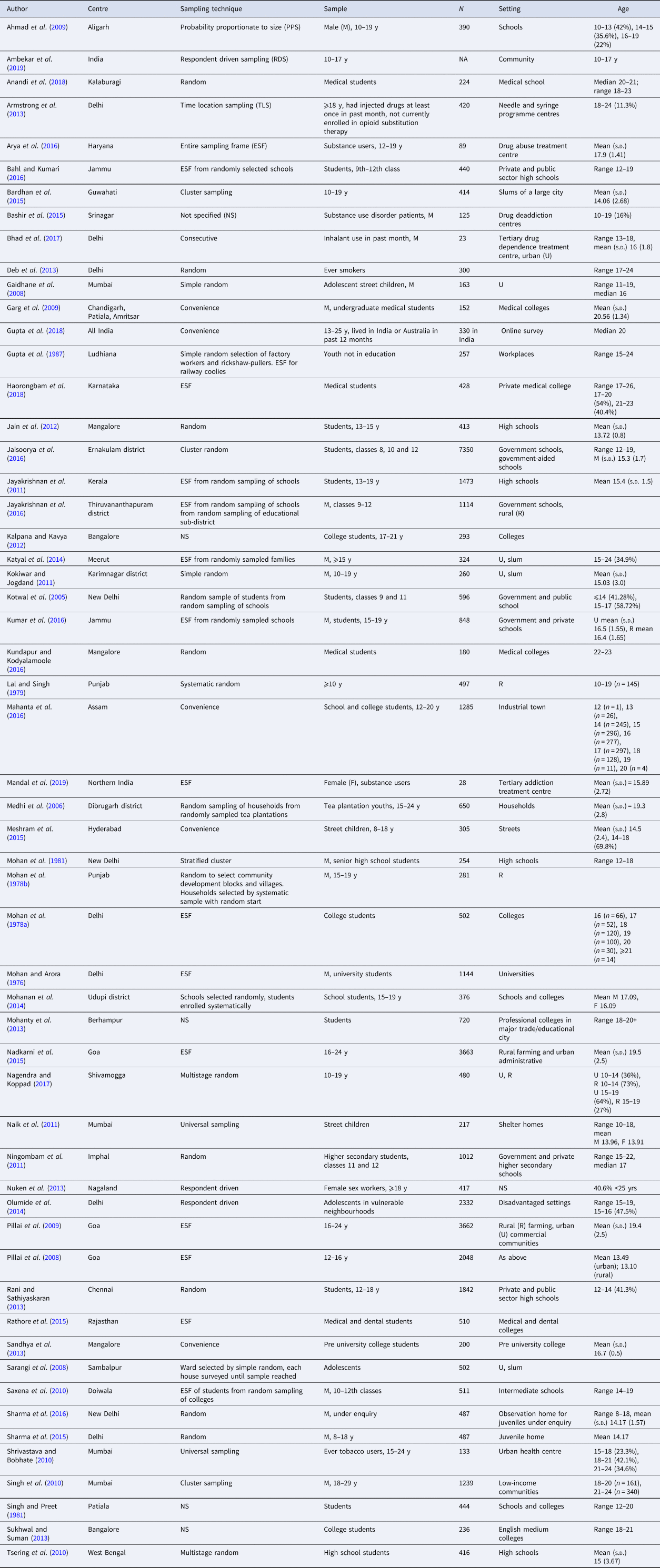

Study descriptions

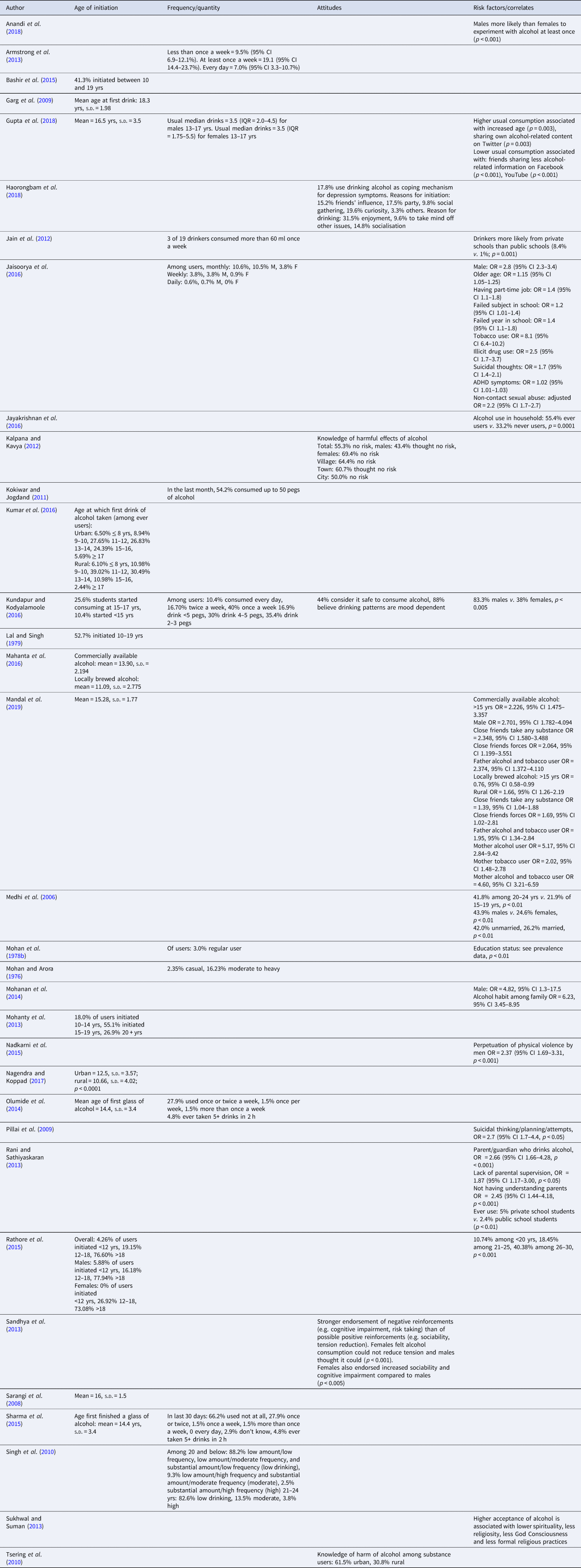

One study was conducted online (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Lam, Pettigrew and Tait2018) and one in a national treatment centre in North India (Mandal et al., Reference Mandal, Parmar, Ambekar and Dhawan2019), both of which potentially had access to participants from across the country (Table 1). All the rest were conducted at a single or multiple settings in a city, town, district, village or state. The sample size of the studies ranged from 23 (Bhad et al., Reference Bhad, Jain, Dhawan and Mehta2017) to 7350 (Jaisoorya et al., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal2016). In studies that reported mean age of the samples, it ranged from 13.10 years (Pillai et al., Reference Pillai, Patel, Cardozo, Goodman, Weiss and Andrew2008) to 20.56 years (Garg et al., Reference Garg, Chavan, Singh and Bansal2009).

Table 1 Description of studies included in the review

Prevalence of alcohol use and AUD

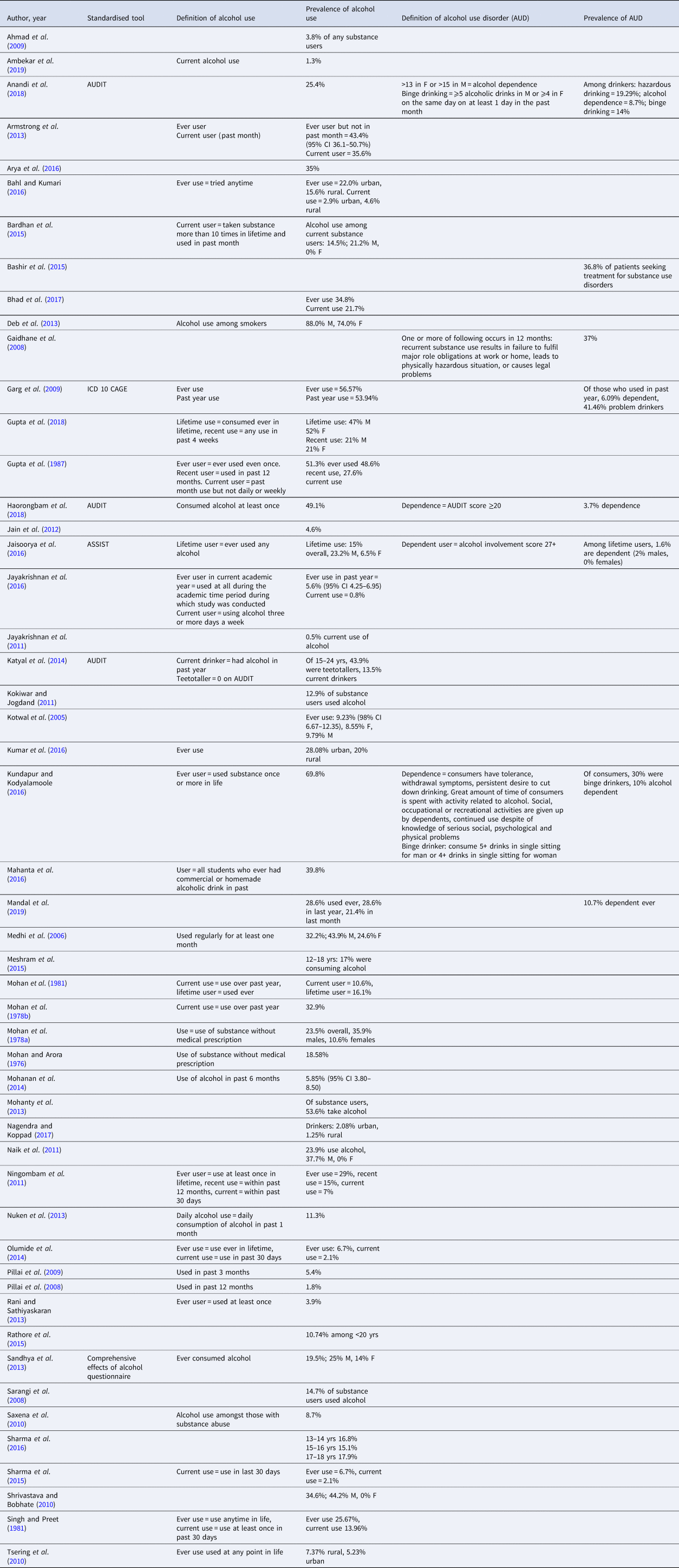

Ever use

The prevalence of ever use or lifetime use, broadly defined as consumption of alcohol at least once in their lifetime, ranged from 3.9% in school students aged 12–18 years (Rani and Sathiyaskaran, Reference Rani and Sathiyaskaran2013) to 69.8% in 22–23-year-old medical students (Kundapur and Kodyalamoole, Reference Kundapur and Kodyalamoole2016) (Table 2). Ever use in females ranged from 6.5% in students from class 8 to class 12 (age 12–19 years) (Jaisoorya et al., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal2016) to 52% in an online survey of adolescents aged 13–17 years (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Lam, Pettigrew and Tait2018), and in males it ranged from 9.79% in students from classes 9 and 11 (age up to 17 years) (Kotwal et al., Reference Kotwal, Thakur and Seth2005) to 47% in an online survey of adolescents aged 13–17 years (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Lam, Pettigrew and Tait2018). The prevalence of ever use in rural areas ranged from 7.37% in high school students (Tsering et al., Reference Tsering, Pal and Dasgupta2010) to 20% in students aged 15–19 years (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Kumar, Shora, Dewan, Mengi and Razaq2016), and in urban areas it ranged from 5.23% in high school students (Tsering et al., Reference Tsering, Pal and Dasgupta2010) to 23.08% in students aged 15–19 years (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Kumar, Shora, Dewan, Mengi and Razaq2016).

Table 2 Prevalence of alcohol use and alcohol use disorders

Current use

The definition of current use of alcohol varied across studies. The more commonly used definitions were alcohol consumption at least once in the past year for which the prevalence ranged from 10.6% in senior high school students aged 12–18 years (Mohan et al., Reference Mohan, Rustagi, Sundaram and Prabhu1981) to 32.9% in 15–19-year-old individuals from rural settings (Mohan et al., Reference Mohan, Sharma, Darshan, Sundaram and Neki1978b); and at least once in the past 30 days (month) for which the prevalence ranged from 2.1% (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Singh, Lal and Goel2015) in 15–19-year olds from disadvantaged urban settings and 35.6% in injectable drug users attending needle and syringe programme centres (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Nuken, Samson, Singh, Jorm and Kermode2013). Some studies did not define current use and others used non-standard definition of current use such as ‘who had not used drugs either daily or weekly in the past month’ (27.6%) (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Narang, Verma, Panda, Garg, Munjal and Singh1987), and ‘habit of using alcohol, 3 days or more a week’ (0.8%) (Jayakrishnan et al., Reference Jayakrishnan, Geetha, Mohanan Nair, Thomas and Sebastian2016). The biggest countrywide survey of substance use in India reported a prevalence of current alcohol use to be 1.3% amongst those aged 10–17 years (Ambekar et al., Reference Ambekar, Agrawal, Rao, Mishra, Khandelwal and Chadda2019).

AUD

Some studies reported the prevalence of AUDs and defined them using standardised tools (Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test [AUDIT], CAGE questionnaire, Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test [ASSIST]), ICD 10 criteria or bespoke definitions. Among medical students (18–23 years) who were drinkers, the prevalence of hazardous drinking was 19.29% (Anandi et al., Reference Anandi, Halgar, Reddy and Indupalli2018), alcohol dependence was 3.7–10% (Kundapur and Kodyalamoole, Reference Kundapur and Kodyalamoole2016; Haorongbam et al., Reference Haorongbam, Sathyanarayana and Dhanashree2018), binge drinking 14–30% (Kundapur and Kodyalamoole, Reference Kundapur and Kodyalamoole2016; Anandi et al., Reference Anandi, Halgar, Reddy and Indupalli2018) and ‘problem drinking’ (not defined) was 41.46% (Garg et al., Reference Garg, Chavan, Singh and Bansal2009). Among students of classes 8, 10 and 12 (12–19 years), 1.6% (2% males, 0% females) of lifetime users had alcohol dependence (Jaisoorya et al., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal2016). In adolescent street children (11–19 years), 37% had AUD defined as recurrent substance use resulting in one or more of the following occurring in 12 months: failure to fulfil major role obligations at work or home leads to a physically hazardous situation, or causes legal problems (Gaidhane et al., Reference Gaidhane, Syed Zahiruddin, Waghmare, Shanbhag, Zodpey and Joharapurkar2008).

Patterns of drinking

Among drinkers, 0.6–10.4% consumed every day (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Nuken, Samson, Singh, Jorm and Kermode2013; Jaisoorya et al., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal2016; Kundapur and Kodyalamoole, Reference Kundapur and Kodyalamoole2016), 19.1–40% consumed at least once a week (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Nuken, Samson, Singh, Jorm and Kermode2013; Kundapur and Kodyalamoole, Reference Kundapur and Kodyalamoole2016), 3.8% consumed weekly (Jaisoorya et al., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal2016), 9.5% consumed less than once a week (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Nuken, Samson, Singh, Jorm and Kermode2013) and 10.6% consumed monthly (Jaisoorya et al., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal2016) (Table 3). Usual median number of drinks consumed among those between 13 and 17 years was 3.5 for both males and females (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Lam, Pettigrew and Tait2018). Among 10–19-year-old males from an urban slum over the past month, 54.2% consumed up to 50 ‘pegs’ of alcohol (Kokiwar and Jogdand, Reference Kokiwar and Jogdand2011). Among males from a low-income community, in those between 18 and 20 years, 88.2% were ‘low drinking’ (low amount/low frequency, low amount/moderate frequency or substantial amount/low frequency), 9.3% were moderate drinking (low amount/high frequency or substantial amount/moderate frequency) and 2.5% were high drinking (substantial amount/high frequency); and in those between 20 and 24 years, 82.6% were low drinking, 13.5% were moderate drinking and 3.8% were high drinking (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Schensul, Gupta, Maharana, Kremelberg and Berg2010).

Table 3 Initiation of, attitudes towards, patterns of and correlates of drinking

Initiation age

The mean age for initiation of drinking ranged from 14.4 to 18.3 years (Table 3). The mean age of initiation was significantly lower in rural areas compared to urban areas [10.66 (s.d. 4.02) v. 12.5 (s.d. 3.57); p < 0.0001] (Nagendra and Koppad, Reference Nagendra and Koppad2017); and locally brewed alcohol [mean (s.d.) 11.09 (2.775)] was initiated at a younger age compared to commercially available alcohol in an industrial town [mean (s.d.) 13.90 (2.194)] (Mahanta et al., Reference Mahanta, Mohapatra, Phukan and Mahanta2016).

Among male substance use disorder patients at drug deaddiction centres, 41.3% had initiated alcohol use between 10 and 19 years (Bashir et al., Reference Bashir, Sheikh, Bilques and Firdosi2015). Among 22–23-year-old medical students, 25.6% had started consuming alcohol between 15 and 17 years, and 10.4% had started consuming alcohol before they were 15 years (Kundapur and Kodyalamoole, Reference Kundapur and Kodyalamoole2016).

In students between 18 and 22 years, 18.0% had initiated drinking between 10 and 14 years, 55.1% had initiated between 15 and 19 years, and 26.9% after 19 years (Mohanty et al., Reference Mohanty, Tripathy, Palo and Jena2013). Among medical and dental students, 4.26% initiated before 12 years, 19.15% initiated between 12 and 18 years, and 76.60% initiated after 18 years (Rathore et al., Reference Rathore, Pankaj, Mangal and Saini2015). Comparing males and females, 5.88% males (v. 0% females) initiated before 12 years, 16.18% (v. 26.92%) initiated between 12 and 18 years, and 77.94% (v. 73.08%) initiated after 18 years (Rathore et al., Reference Rathore, Pankaj, Mangal and Saini2015). Finally, comparing urban and rural drinkers, 6.50% urban drinkers (v. 6.10% rural) initiated before 8 years, 8.94% (v. 10.98%) initiated between 9 and 10 years, 27.65% (v. 39.02%) initiated between 11 and 12 years, 26.83% (v. 30.49%) initiated between 12 and 14 years, 24.39% (v. 10.98%) initiated between 15 and 16 years, and 5.69% (v. 2.44%) initiated after 17 years (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Kumar, Shora, Dewan, Mengi and Razaq2016).

Knowledge and attitudes

Overall, 55.3% of college-going students (17–21 years) believed that there was no risk of harmful effects of alcohol; with more females than males who believed that there was no risk (69.4% v. 43.4%); and a higher proportion from villages (64.4%) thought there was no risk as compared to those from towns (60.7%) or cities (50.0%) (Kalpana and Kavya, Reference Kalpana and Kavya2012) (Table 3). Among medical students (22–23 years), 44% considered it safe to consume alcohol, and 88% believe drinking patterns are mood-dependent (Kundapur and Kodyalamoole, Reference Kundapur and Kodyalamoole2016).

In medical students (17–23 years), reasons for initiation of drinking included curiosity (19.6%), attending a party (17.5%), friends' influence (15.2%) and social gatherings (9.8%); and reasons for continued use included enjoyment (31.5%), as a coping mechanism for depressive symptoms (17.8%), socialisation (14.8%) and to take mind off other issues (9.6%) (Haorongbam et al., Reference Haorongbam, Sathyanarayana and Dhanashree2018). Among college-going students (mean age 16.7 years; s.d. 0.5) there was a stronger endorsement of negative reinforcements (e.g. cognitive impairment, risk taking) than of possible positive reinforcements (e.g. sociability, tension reduction); and compared to males, significantly more females felt alcohol consumption could not reduce tension and endorsed increased sociability and cognitive impairment (Sandhya et al., Reference Sandhya, Carol, Kotian and Ganaraja2013). Knowledge of harm of alcohol among substance users was greater in adolescents from urban than rural areas (61.5% v. 30.8%) (Tsering et al., Reference Tsering, Pal and Dasgupta2010).

Risk factors/correlates

The cross-sectional nature of the studies only allowed the examination of correlates of alcohol use (Table 3). Alcohol consumption was associated with being male (Medhi et al., Reference Medhi, Hazarika and Mahanta2006; Mohanan et al., Reference Mohanan, Swain, Sanah, Sharma and Ghosh2014; Jaisoorya et al., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal2016; Kundapur and Kodyalamoole, Reference Kundapur and Kodyalamoole2016; Anandi et al., Reference Anandi, Halgar, Reddy and Indupalli2018; Mandal et al., Reference Mandal, Parmar, Ambekar and Dhawan2019), older age (Medhi et al., Reference Medhi, Hazarika and Mahanta2006; Rathore et al., Reference Rathore, Pankaj, Mangal and Saini2015; Jaisoorya et al., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal2016; Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Lam, Pettigrew and Tait2018; Mandal et al., Reference Mandal, Parmar, Ambekar and Dhawan2019) and going to private rather than public schools (Jain et al., Reference Jain, Dhanawat, Kotian and Angeline2012; Rani and Sathiyaskaran, Reference Rani and Sathiyaskaran2013). Specifically for locally brewed alcohol, it was associated with younger age and rural residence (Mandal et al., Reference Mandal, Parmar, Ambekar and Dhawan2019). Alcohol consumption was associated with having a part-time job, and failing a subject or a year in school (Jaisoorya et al., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal2016).

Alcohol use in adolescents was associated with parental/guardian's use of alcohol or tobacco, lack of parental supervision, and not having ‘understanding’ parents (Rani and Sathiyaskaran, Reference Rani and Sathiyaskaran2013; Mohanan et al., Reference Mohanan, Swain, Sanah, Sharma and Ghosh2014; Jayakrishnan et al., Reference Jayakrishnan, Geetha, Mohanan Nair, Thomas and Sebastian2016; Mandal et al., Reference Mandal, Parmar, Ambekar and Dhawan2019). Alcohol use decreased with a decrease in the frequency of friends sharing alcohol-related information on Facebook and YouTube; and increased frequency of sharing personal alcohol-related content on Twitter was associated with an increase in alcohol use (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Lam, Pettigrew and Tait2018). Alcohol consumption was also associated with close friends using substances (any type) or peer pressure to drink alcohol (Mandal et al., Reference Mandal, Parmar, Ambekar and Dhawan2019).

Alcohol consumption was associated with tobacco use, illicit drug use, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms, suicidal thinking, planning and attempts, and non-contact sexual abuse and perpetuation of violence (Nadkarni et al., Reference Nadkarni, Dean, Weiss and Patel2015; Jaisoorya et al., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal2016). Finally, higher acceptance of alcohol is associated with lower spirituality, less religiosity, less ‘God Consciousness’ and less formal religious practices (Sukhwal and Suman, Reference Sukhwal and Suman2013).

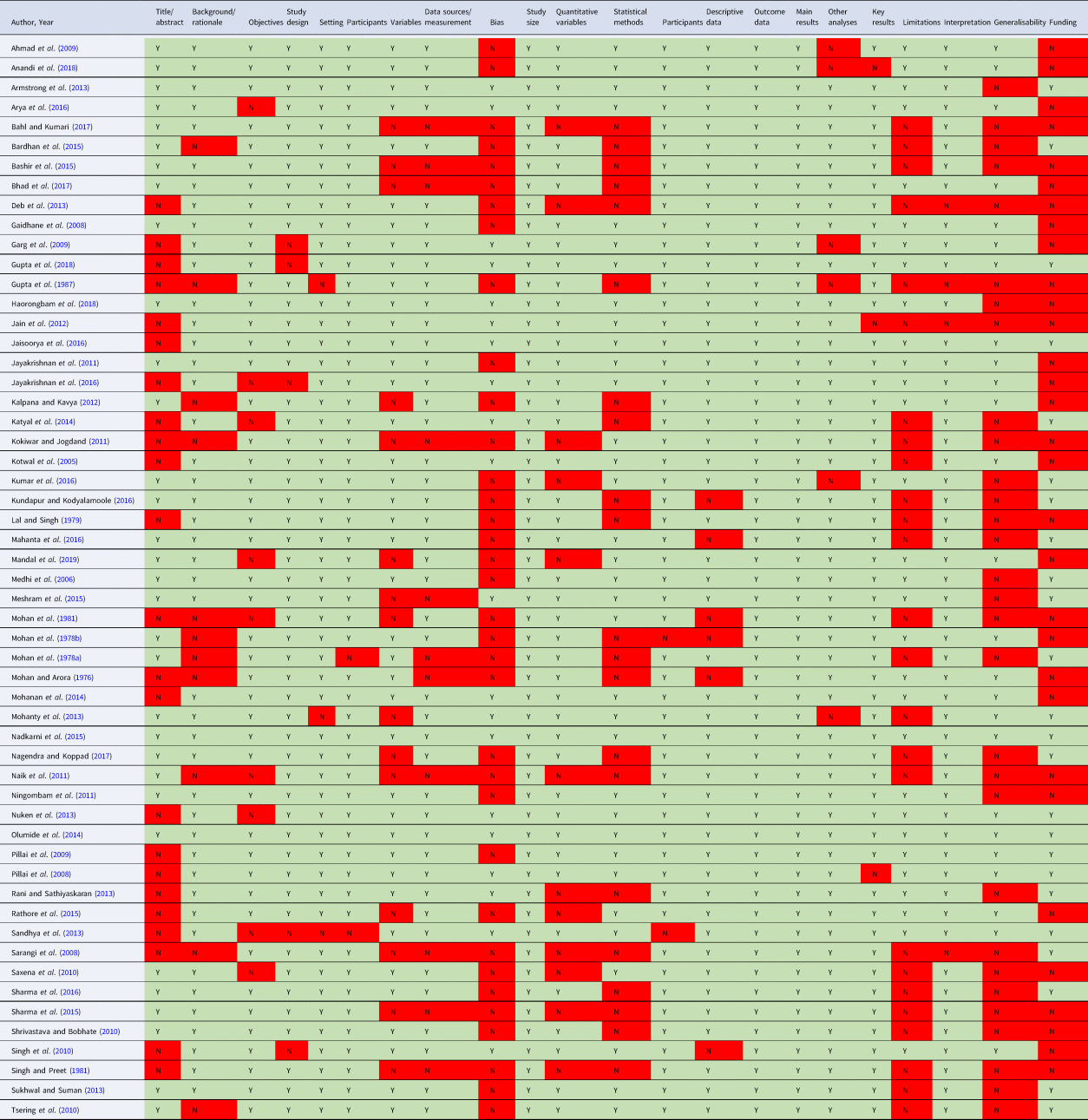

Quality of reporting studies

In 42 of the 57 studies, there was appropriate reporting of more than 70% of the 22 STROBE criteria (Appendix B). Only one study reported on all the 22 criteria (Nadkarni et al., Reference Nadkarni, Dean, Weiss and Patel2015). For 15 of the 22 criteria, there was appropriate reporting in more than 70% of the studies. The poorest reporting was about study biases, generalisability of the findings, and role of the funder.

Discussion

The existing evidence base has several limitations which preclude a robust synthesis and any conclusions we draw are, at best, exploratory in nature. Although the information about AUDs is relatively limited, the prevalence among drinkers appears to be high, and the patterns of drinking in a reasonably high proportion were suggestive of risky drinking (heavy drinking that puts the drinker at risk of developing problems), especially considering that this is a young population with a relatively short drinking history.

This is consistent with the steady rise in recorded alcohol consumption in most developing countries, albeit from relatively low base prevalence rates. It also parallels the increases in adult per capita consumption of alcohol and heavy episodic drinking that have been observed in India and other developing economies in east Asia, south Asia and southeast Asia (Shield et al., Reference Shield, Manthey, Rylett, Probst, Wettlaufer, Parry and Rehm2020). Amongst adolescents, the prevalence of current alcohol use in Sri Lanka was 3.4% (95% CI 2.6–4.3) (Senanayake et al., Reference Senanayake, Gunawardena, Kumbukage, Wickramasnghe, Gunawardena, Lokubalasooriya and Peiris2018), lifetime alcohol use in males was 45% (26% risky drinking) in Pakistan (Shahzad et al., Reference Shahzad, Kliewer, Ali and Begum2020), alcohol use was reported by 19% from traditional non-alcohol using ethnic groups and 40% from traditional alcohol using ethnic groups in Nepal (Parajuli et al., Reference Parajuli, Macdonald and Jimba2015), and 13% in Bhutan (Norbu and Perngparn, Reference Norbu and Perngparn2014).

The data about patterns of drinking observed among adolescents in India are inconclusive but there appears to be some tendency towards heavy drinking. Among adolescents across several countries, there are consistent reports of binge drinking as a social norm among peer groups (Russell-Bennett et al., Reference Russell-Bennett, Hogan and Perks2010). The prevalence of binge drinking increases from age 15–19 years to the age of 20–24 years, and among drinkers, binge drinking is higher among the 15–19 years age group compared with the total population of drinkers (World Health Organization, 2018). This means that 15–24-year-old current drinkers often drink in heavy drinking sessions, and hence, except for the Eastern Mediterranean Region, the prevalence of such drinking among drinkers is high in adolescents (around 45–55%) (World Health Organization, 2018).

In India, the age of initiation commonly was mid- to late-teens; and male gender, rural residence and locally brewed alcohol were associated with earlier initiation of drinking. Across most of the world, initiation of alcohol use among adolescents takes place at an early age, usually before the age of 15 years. Among 15-year-olds, there is a high prevalence of alcohol use (50–70%) during the past 30 days in many countries of the Americas, Europe and Western Pacific; and the prevalence is relatively lower in African countries (10–30%) (World Health Organization, 2018). However, across the world, there is a huge variation in alcohol use among boys and girls of 15 years of age and vary from 1.2% to 74.0% in boys and 0% to 73.0% in girls (World Health Organization, 2018). Finally, with the strategic targeting of adolescents as alcohol consumers by the industry, increasing overall population prevalence and normalisation of drinking alcohol, and the increasing normalisation by virtue of learning more about how adolescents in other countries drink, one could speculate that the age of initiation would reduce and prevalence of alcohol consumption in adolescents in India would rise, in the coming years.

In India, knowledge about alcohol and its potential harms was limited in rural areas. The reasons for starting and continuing drinking were a mix of expected enhancement of positive experiences and dampening of negative affect. This is consistent with findings in Indian adults where alcohol consumption was seen to be mainly associated with expectations about reduction in psychosocial stress and providing pleasure (Nadkarni et al., Reference Nadkarni, Dabholkar, McCambridge, Bhat, Kumar, Mohanraj and Patel2013). Across the world, adolescents primarily report drinking for social motives or enjoyment – enjoyment (Argentina) (Jerez and Coviello, Reference Jerez and Coviello1998), to make nights out more pleasurable (UK) (Plant et al., Reference Plant, Bagnall and Foster1990) and being social (Canada) (Kairouz et al., Reference Kairouz, Gliksman, Demers and Adlaf2002). Coping motives, on the other hand, are less common, but are associated with AUDs later in adulthood (Carpenter and Hasin, Reference Carpenter and Hasin1999). The difference in drinking motives between adolescents from India (a mix of pleasure and coping) and other countries (primarily pleasure), and the similarity between reasons given by Indian adolescents and Indian adults, possibly reflect contextual/cultural differences and will have implications on transferability of interventions from other contexts and wider age-applicability of interventions developed for adults in India.

We can broadly organise our findings about correlates for drinking into socio-demographic characteristics (e.g. age, gender), immediate environment (e.g. parents, friends, digital space) and clinical correlates (e.g. other substance use, suicidal thoughts). Risk and protective factors influencing the use of alcohol in adolescents are both proximal and distal factors and include individual cognitions and peer-influence risk factors (e.g. attitudes favourable to alcohol use and peer drinking), family environment (e.g. parental discipline and family bonding) and school context (e.g. academic commitment and achievement) (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Schulenberg, O'Malley, Bachman and Johnston2003; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Miles, Austin, Camargo and Colditz2007; Patock-Peckham and Morgan-Lopez, Reference Patock-Peckham and Morgan-Lopez2010). Most commonly adolescent males drink more often than adolescent females, but there has been some blurring of the distinction between the genders in developed countries (Currie et al., Reference Currie, Roberts, Settertobulte, Morgan, Smith and Samdal2004; Hibell et al., Reference Hibell, Guttormsson, Ahlström, Balakireva, Bjarnason, Kokkevi and Kraus2009). This convergence of drinking patterns is particularly seen in the Nordic countries, Ireland, the UK and the USA, and manifests as almost equal prevalence rates for consumption of spirits and similar frequency of intoxication for both genders (Hibell et al., Reference Hibell, Guttormsson, Ahlström, Balakireva, Bjarnason, Kokkevi and Kraus2009). Evidence from South Asian countries indicates that male gender, age greater than 14 years, depression, religious beliefs, parental/family members' drinking, reduced parental supervision, peer-drinking/pressure/approval and urban neighbourhood are associated with adolescent drinking (Athauda et al., Reference Athauda, Peiris-John, Ameratunga, McCool and Wickremasinghe2020).

The most important study finding is that despite several studies over the years, the evidence base has several gaps, notably the limited geographical span, small sample sizes and heterogeneous definitions of alcohol use and AUDs. Of particular importance are the various sample selection strategies, especially for the smaller studies, which limit the generalisability of findings. Another gap is the lack of consistency in the measurement of alcohol use, which is especially critical in a context where ‘standard drink’ does not translate semantically or literally into the vernacular, and there is an immense variability in the types of alcoholic beverages (commercial, licit non-commercial, illicit home-brewed, adulterated alcoholic beverages) and in the type and size of vessels from which alcohol is poured or consumed in. Additionally, there were several gaps in the reporting of many studies which raise questions about their internal validity. In the absence of critical information such as data sources, measurement and statistical methods, it is difficult to draw an inference about the robustness of the studies which had inadequate reporting (Appendix B). Finally, although the cross-sectional design of the studies allows us to examine the prevalence of alcohol use and AUDs, it limits the conclusions that we can draw about causal relationships between the various potential risk factors and alcohol use/AUDs.

Although the included studies are not without limitations that are important to consider before drawing conclusions, this synthesis allows us to get a reasonable understanding of alcohol use among adolescents in India and derive preliminary conclusions that the prevalence is high and rising, which brings with it the attendant burden of the associated adverse impacts. Furthermore, despite the gaps in the available data, it carries several implications for policy makers. Because alcohol is an important cause of motor vehicle accidents and suicide, which are the leading causes of death among adolescents in India (Joshi et al., Reference Joshi, Alim, Maulik and Norton2017), interventions that seek to help adolescents avoid or better manage alcohol consumption are a priority. Examples of such evidence-based interventions include public health engagement campaigns to increase awareness of alcohol-related harms, advocacy through community engagement/mobilisation to promote better enforcement of laws related to drinking, engagement with alcohol outlets to promote responsible beverage service, and engaging adolescents and families including through peer-led classroom curriculum to enhance the resilience of adolescents, improve family socialisation and increase awareness of alcohol-related harms (McLeroy et al., Reference McLeroy, Norton, Kegler, Burdine and Sumaya2003; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Brown, Oesterle, Arthur, Abbott and Catalano2008; Wakefield, Loken, and Hornik, Reference Wakefield, Loken and Hornik2010; Hallgren and Andréasson, Reference Hallgren and Andréasson2013). The most important implication of our review, however, is the need to develop the very nascent literature base through robust studies, especially longitudinal research that can support evidence-based prevention interventions and policy change. Future studies should focus on increasing their geographical span and sample sizes, ensure the use of standard definitions of alcohol use and AUDs which are consistent with global literature, and acknowledge and examine contextual variations in types of alcoholic beverages and type and size of vessels from which alcohol is poured or consumed in. Introducing such measures will enhance the robustness, validity and generalisability of the findings; and allow for better comparisons over time and geography. This would require greater support from the Government through ensuring availability of in-country research funding, prioritisation of the issue and utilisation of the evidence generated to inform its policy on alcohol.

Our review is limited by our inclusion criterion related to language. However, this might not be a major limitation considering that peer-reviewed journals in India are only in English as far as we are aware, and researchers generally disseminate their outputs in English language journals. Our review's major strength lies in its originality (the first such review to comprehensively map the landscape of substance use among adolescents in India), use of robust processes (e.g. double screening) and examination of grey literature to identify any relevant evidence.

To conclude, the evidence base for alcohol use amongst adolescents in India needs further and deeper exploration, but in the meanwhile, the available evidence allows us to get a preliminary understanding of the issue and to make a case for policy action to tackle alcohol consumption in this age group.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2021.48

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Professor Pratima Murthy, Professor Vivek Benegal and Professor Atul Ambekar for helping us identify relevant grey literature.

Financial support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

There are no real or perceived conflicts of interest in undertaking or publishing this research.

Ethical standards

As this is a systematic review, it did not involve any direct data collection from human subjects.

Appendix A: Search strategy

1. abuse.tw

2. abuse/

3. misuse.tw

4. misuse/

5. use.tw

6. use/

7. disorders.tw

8. disorders/

9. withdraw*.tw

10. withdraw*/

11. withdrawal syndrome.tw

12. withdrawal syndrome/

13. screening.tw

14. screening/

15. overdose.tw

16. overdose/

17. megadose.tw

18. megadose/

19. dependen*.tw

20. dependen*/

21. intoxication.tw

22. intoxication/

23. harm*.tw

24. harm*/

25. hazard*.tw

26. hazard*/

27. behavior.tw

28. behavior/

29. Addict*.tw

30. Addict*/

31. alcoholi*.tw

32. alcoholi*/

33. delirium.tw

34. delirium/

35. binge drink*.tw

36. binge drink*/

37. consumption.tw

38. consumption/

39. drink*.tw

40. drink*/

41. sniff*.tw

42. sniff*/

43. snort*.tw

44. snort*/

45. cessation.tw

46. cessation/

47. smok*.tw

48. smok*/

49. inject*.tw

50. inject*/

51. OR (1–50)

52. Drug.tw

53. Drug/

54. Substance.tw

55. Substance/

56. Alcohol.tw

57. Alcohol/

58. ‘purple drank’.tw

59. ‘purple drank’/

60. 1plsd.tw

61. lplsd/

62. unclassified drug.tw

63. unclassified drug/

64. 2cb.tw

65. 2cb/

66. chlorobenzoic acid derivative.tw

67. chlorobenzoic acid derivative/

68. 4fa.tw

69. 4fa/

70. Ecstasy.tw

71. Ecstasy/

72. methadone.tw

73. methadone/

74. morphine.tw

75. morphine/

76. buprenorphine.tw

77. buprenorphine/

78. diamorphine.tw

79. diamorphine/

80. amphetamine.tw

81. amphetamine/

82. amphetamine derivative.tw

83. amphetamine derivative/

84. AUD.tw

85. AUD/

86. bidi.tw

87. bidi/

88. tobacco.tw

89. tobacco/

90. cigarette.tw

91. cigarette/

92. electronic cigarette.tw

93. electronic cigarette/

94. e-cig.tw

95. e-cig/

96. beedi.tw

97. beedi/

98. benzodiazepine derivative.tw

99. benzodiazepine derivative/

100. benzodiazepine.tw

101. benzodiazepine/

102. bhang.tw

103. bhang/

104. Hashish.tw

105. Hashish/

106. cannabi*.tw

107. cannabi*/

108. ‘brown sugar’.tw

109. ‘brown sugar’/

110. medical cannabi*.tw

111. medical cannabi*/

112. tetrahydrocannabinol.tw

113. tetrahydrocannabinol/

114. hash.tw

115. hash/

116. charas.tw

117. charas/

118. cocaine.tw

119. cocaine/

120. cocaine derivative.tw

121. cocaine derivative/

122. smack.tw

123. smack/

124. crack.tw

125. crack/

126. syrup.tw

127. syrup/

128. chlorpheniramine.tw

129. chlorpheniramine/

130. ‘cough syrup’.tw

131. ‘cough syrup’/

132. codeine.tw

133. codeine/

134. dexamphetamine.tw

135. dexamphetamine/

136. dextromethorphan.tw

137. dextromethorphan/

138. 3,4 methylenedioxyamphetamine.tw

139. 3,4 methylenedioxyamphetamine/

140. psychedelic agent.tw

141. psychedelic agent/

142. ganja.tw

143. ganja/

144. 4 aminobutyric acid.tw

145. 4 aminobutyric acid/

146. 4 hydroxybutyric acid.tw

147. 4 hydroxybutyric acid/

148. GHB.tw

149. GHB/

150. Ketamine.tw

151. Ketamine/

152. glue.tw

153. glue/

154. heroin.tw

155. heroin/

156. nicotine.tw

157. nicotine/

158. diamorphine.tw

159. diamorphine/

160. inhalant.tw

161. inhalant/

162. kava extract.tw

163. kava extract/

164. kava.tw

165. kava/

166. smokeless tobacco.tw

167. smokeless tobacco/

168. khaini.tw

169. khaini/

170. laughing gas.tw

171. laughing gas/

172. nitrous oxide.tw

173. nitrous oxide/

174. LSD.tw

175. LSD/

176. Lysergic acid diethylamide.tw

177. Lysergic acid diethylamide/

178. Acid.tw

179. Acid/

180. Lucy.tw

181. Lucy/

182. magic mushroom.tw

183. magic mushroom/

184. hallucinogenic fungus.tw

185. hallucinogenic fungus/

186. mari#uana.tw

187. marj#uana/

188. MDMA.tw

189. MDMA/

190. Midomafetamine.tw

191. Midomafetamine/

192. amphetamine.tw

193. amphetamine/

194. methamphetamine.tw

195. Methamphetamine/

196. Crystal meth.tw

197. Crystal meth/

198. Amobarbital.tw

199. Amobarbital/

200. Methylphenidate.tw

201. Methylphenidate/

202. Modafinil.tw

203. Modafinil/

204. Morphine.tw

205. Morphine/

206. Opiod*.tw

207. Opiod*/

208. Opiate*.tw

209. Opiate*/

210. Opium.tw

211. Opium/

212. ‘paint thinner’.tw

213. ‘paint thinner’/

214. promethazine.tw

215. promethazine/

216. psilocybin#.tw

217. psilocybin#/

218. Quaalude.tw

219. Quaalude/

220. Methaqualone.tw

221. Methaqualone/

222. Salvia divinorum.tw

223. Salvia divinorum/

224. Psychotropic agent.tw

225. Psychotropic agent/

226. Snuff.tw

227. Snuff/

228. Chewing tobacco.tw

229. Chewing tobacco/

230. Tramadol.tw

231. Tramadol/

232. Viagra.tw

233. Viagra/

234. Sildenafil.tw

235. Sildenafil/

236. Z-class.tw

237. Z-class/

238. Zdrug.tw

239. Zdrug/

240. Eszopiclone.tw

241. Eszopiclone/

242. Zaleplon.tw

243. Zaleplon/

244. Zoipidem.tw

245. Zoipidem/

246. Zopiclone.tw

247. Zopiclone/

248. Hypnotic agent.tw

249. Hypnotic agent/

250. Prescription durg.tw

251. Prescription drug/

252. Prescription medicine.tw

253. Prescription medicine/

254. Prescription medication.tw

255. Prescription medication/

256. OR (52-255)

257. adolescen*.tw

258. adolescen*/

259. child*.tw

260. child*/

261. youth*.tw

262. youth*/

263. student*.tw

264. student*/

265. girl*.tw

266. girl*/

267. teen*.tw

268. teen*/

269. boy*.tw

270. boy*/

271. young adult*.tw

272. young adult*/

273. young*.tw

274. young*/

275. OR (257-274)

276. india.tw

277. India/

278. ‘Indian union’.tw

279. ‘Indian union’/

280. Andaman and Nicobar Island*.tw

281. Andaman and Nicobar Island/

282. Andhra Pradesh.tw

283. Andhra Pradesh/

284. Arunachal Pradesh.tw

285. Arunachal Pradesh/

286. Assam.tw

287. Assam/

288. Bihar.tw

289. Bihar/

290. Dadra and Nagar Haveli.tw

291. Dadra and Nagar Haveli/

292. Chhattisgarh.tw

293. Chhattisgarh/

294. Daman and Diu.tw

295. Daman and Diu/

296. National Capital Territory of New Delhi.tw

297. National Capital Territory of New Delhi/

298. Delhi.tw

299. Delhi/

300. Goa.tw

301. Goa/

302. Gujarat.tw

303. Gujarat/

304. Haryana.tw

305. Haryana/

306. Himachal Pradesh.tw

307. Himachal Pradesh/

308. Jammu and Kashmir.tw

309. Janmu and Kashmir/

310. Janmu.tw

311. Janmu/

312. Kashmir.tw

313. Kashmir/

314. Jharkhand.tw

315. Jharkhand/

316. Karnataka.tw

317. Karnataka/

318. Mysore.tw

319. Mysore/

320. Kerala.tw

321. Kerala/

322. Travancore-Cochin.tw

323. Travancore-Cochin/

324. Madhya Pradesh.tw

325. Madhya Pradesh/

326. Madhya Bharat.tw

327. Madhya Bharat/

328. Maharashtra.tw

329. Maharashtra/

330. Manipur.tw

331. Manipur/

332. Meghalaya.tw

333. Meghalaya/

334. Mizoram.tw

335. Mizoram/

336. Nagaland.tw

337. Nagaland/

338. Odisha.tw

339. Odisha/

340. Orissa.tw

341. Orissa/

342. Punjab.tw

343. Punjab/

344. Chandigarh.tw

345. Chandigarh/

346. Rajasthan.tw

347. Rajasthan/

348. Sikkim.tw

349. Sikkim/

350. Tamil Nadu.tw

351. Tamil Nadu/

352. Madras State.tw

353. Madras State/

354. Telangana.tw

355. Telangana/

356. Tripura.tw

357. Tripura/

358. Uttarakhand.tw

359. Uttarakhand/

360. Uttaranchal.tw

361. Uttaranchal/

362. Uttar Pradesh.tw

363. Uttar Pradesh/

364. United Provinces.tw

365. United Provinces/

366. West Bengal.tw

367. West Bengal/

368. Mizoram.tw

369. Mizoram/

370. Nagaland.tw

371. Nagaland/

372. Lakshadweep.tw

373. Lakshadweep/

374. P#d#cherry.tw

375. P#d#cherry/

376. OR (276–375)

377. 51 AND 256 AND

Appendix B: Quality of reporting of peer-reviewed studies included in the review (excluding the report)