Women's under-representation in global health leadership

Women are under-represented in leadership in global health (GH) across academic, governmental, and non-governmental institutions [Reference Barry1–Reference Downs4]. Across 191 countries, only 51 have a woman minister of health [Reference Magar5]. At Emory University, 91% of undergraduate minors and 84% of masters students in GH are women; yet, 75% of full professors (31 of 41) and 75% (six of eight) of named professors in GH are men. Women, including women of color, sexual minority women, indigenous women, other minority women groups, and women from lower income countries, remain disproportionately under-represented in leadership positions [6]. Women from different backgrounds face disparate barriers to leadership, which must be overcome to support the leadership potential of all women in GH [Reference Bowleg7].

Rationale for women's leadership in GH

Women's representation in GH leadership matters on the simple grounds of justice. Empirically, women make up 50% of the world's population, bear the unique burden of certain causes of death [Reference Alkema8], experience more years than men of life lost due to disability [Reference Vos9], comprise at least two-thirds of the GH workforce [Reference Magar5], and provide disproportionate unpaid care for the sick [Reference Magar5, Reference Berg and Woods10]. Women contribute around US$3 trillion to GH care, but nearly half of this (2.4% of global gross domestic product) is unpaid [Reference Dhatt2]. Given women's unique needs and contributions, women should have equal formal, descriptive, and substantive representation in the ranks of GH leadership. Equality in formal representation means having the same opportunities as men to participate in leadership, without discrimination based on gender or other intersecting identities. Equality in descriptive representation means that women are represented in equal numbers in positions of leadership. Equality in substantive representation means that women's interests are advocated in decision-making circles. Emerging evidence suggests that women need to be in leadership to have their interests represented [Reference Swers and Rouse11, Reference Wängnerud12].

Call to action and role of women's mentorship networks

The recent inaugural Women Leaders in Global Health (WLGH) conference established principles to advance women's leadership in GH. Recommended strategies included increasing the visibility of women by ensuring gender balance in all spheres of academia, nominating and promoting women for important committees and awards, advocacy for a culture that values work-life integration, eliminating gender gaps in pay, cultivating thought leadership among women professionals, addressing data gaps that mask persistent gender disparities in leadership, and promoting accountability. One strategic priority of the WLGH Initiative includes mentorship for women's leadership in GH.

GROW empowerment model for mentoring women leaders in global health

Given this ambitious agenda, models for mentorship are needed to position women for leadership in GH [Reference Talib and Barry3, Reference Downs4]. Mentorship can be a powerful tool to enhance the capabilities of individual women and to strengthen their collective capabilities to advance in the ranks. Our focus on mentoring to enhance capabilities differs from the typical psychosocial and professional outcomes that feature in the mentoring literature [Reference Hopwood13, Reference Dominguez14]. Enhancing individual and collective capabilities are essential to empower women for leadership in GH.

Here, we describe the theory of change and present pilot data for the mentorship model, Global Research for Women (GROW). GROW is an interdisciplinary, global initiative to catalyze empowerment, health, and freedom from violence for women and girls globally. Our guiding principle is that women's and girls’ empowerment is a pillar of sustainable development and is inextricably linked with their health and freedom from violence. Our strategic priorities are to advance scholarship, to cultivate leadership, and to generate dialogue that catalyzes social change through evidence-based policies, programs, and collective action for women's and girls’ empowerment.

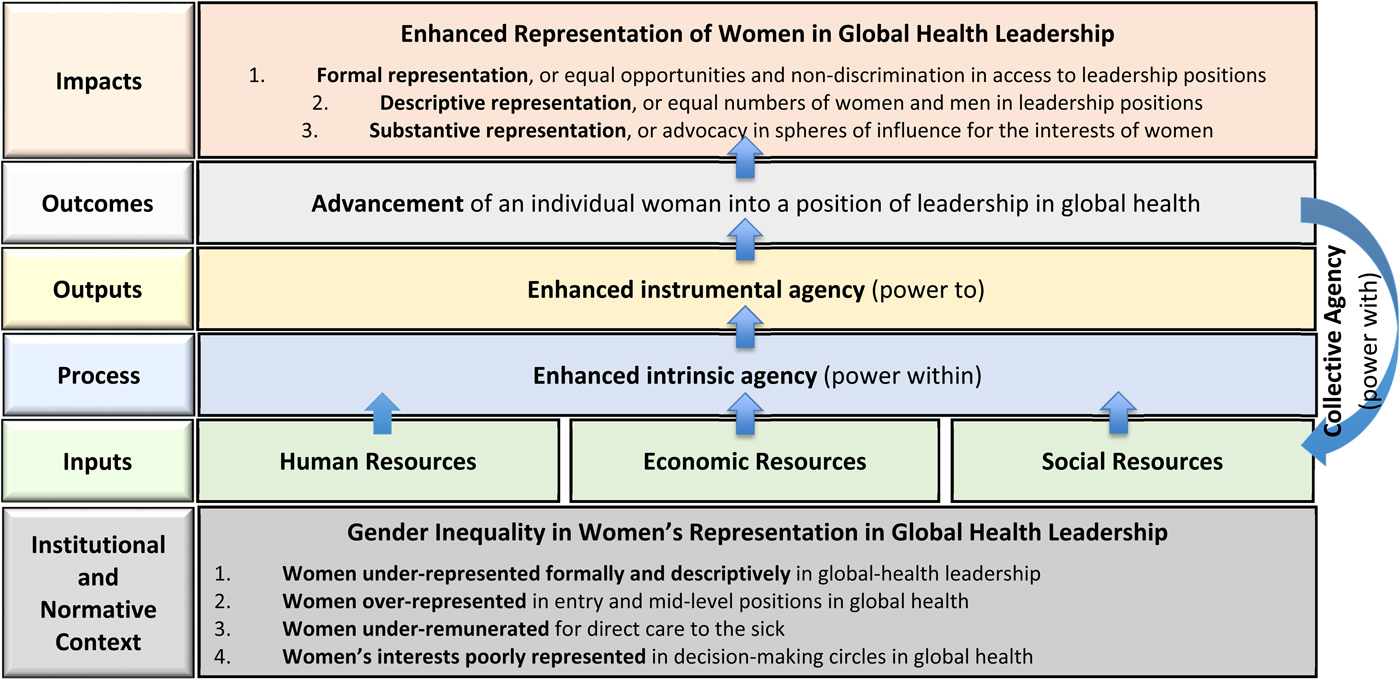

Inclusive with all women and with men, the GROW mentorship model is adapted from a theory for women's empowerment developed by feminist economist, Naila Kabeer [Reference Kabeer15]. We define women's empowerment in GH as the process by which women acquire new human, economic, and social resources, which enable them to exercise agency, or the capacity to make strategic life choices to enhance their professional development in a context in which these capabilities were once denied. Below, we describe the components of this empowerment-based mentorship model to advance women's careers in GH (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. GROW empowerment model for mentorship and the advancement of women's leadership in global health.

Expanding human resources involves advanced theoretical and methodological training enabling scholars to acquire new knowledge and skills in subfields of GH; opportunities to lead and to co-author publications with our global network of affiliates; in-country practicums to build field experience; guidance on how to build effective teams for research, practice, or advocacy; discussions on emotional intelligence, including skills to negotiate on one's own behalf and to manage professional conflicts; and training on ethical principles for robust work in GH.

Investing economic resources includes advocacy for undergraduate, graduate, and post-graduate scholarships; recommendations for prominent internal and external fellowships, awards, and positions; mentorship on grant writing; opportunities to participate on externally funded team projects at all stages of career; and financial support to attend and to present at professional conferences.

Expanding social resources includes integration into interdisciplinary, project-based teams and peer groups to build collaborations; exposure to formal and informal professional networks; opportunities to attend professional conferences; introductions to professionals with similar career interests; and in-country internships to deepen global networks. Social resources also include the amplification of accomplishments via the media, including press releases, webinars, newsletters (http://www.growemory.org/archives), blogs (http://www.growemory.org/growblog), and social-media posts.

Agency is an intermediate outcome that may arise from the above enabling resources. Agency encompasses an intrinsic belief in one's capabilities, the strategic enactment of one's aspirations or preferences, and the collective action of women to advance women's leadership in GH. Intrinsic agency, or power within, entails the development of self-confidence, self-efficacy, and a critical awareness of one's professional worth and potential contributions. Instrumental agency, or power to, entails the enactment of strategic, or meaningful, decisions that advance one's career. Collective agency, or power with, entails a group's shared belief in its joint capabilities to organize and to execute mutually agreed actions for shared achievements. More than the sum of individual agencies, collective agency emerges from the interactive, coordinated, and synergistic dynamics of the group [Reference Bandura16]. Intrinsic and instrumental agency, as individual-level outcomes of mentoring, are rarely examined in mentoring models [Reference Hopwood13, Reference O'Meara17]. Collective agency has never been conceptualized or measured as an outcome of network-based models for mentoring. Through these pathways, GROW leverages the achievements of women leaders in GH to benefit women at all career stages.

An overarching theme of GROW is feminist praxis. Research documenting the inequalities, injustices, and violence faced by women and girls, and advocacy for women's equality, has been met with scrutiny, and even backlash [Reference Dragiewicz and Mann18]. GROW trains scholars to develop new theory and to apply rigorous methods, producing exceptional evidence to meet this resistance and to inform debates that advance women's interests. GROW's mission to empower early career professionals to produce scholarship of exceptional quality necessitates robust, feminist approaches to the design, implementation, analysis, and dissemination of research [19]. Mentorship from senior GROW affiliates on feminist ethical guidelines enables scholars to balance participant autonomy and safety in each study of empowerment and violence. GROW's networks provide opportunities for training on disciplinary standards within this specialized field.

Testimonials from GROW mentees

In Table 1, we present qualitative testimonials from graduates who received a pilot implementation of GROW since 2015. Qualitative evidence suggests that the focus on empowerment is attractive and capability enhancing. Trainees highlight the relevance of an interdisciplinary network supporting mutual growth, and rigorous research undergirded by a shared commitment to improve collectively the lives of women and girls. Excerpts from testimonials contextualize the capability-enhancing benefits realized by graduates mentored using the GROW framework. These testimonials reveal how GROW mentees have benefitted from the resources provided and the enhanced agency cultivated to advance their careers in GH. More information about the GROW network, access to scientific resources, and testimonials of the capability-enhancing benefits of GROW can be found at http://growemory.org/.

Table 1. Testimonials of the impact of GROW mentorship on the capabilities for leadership in global health

Next steps

Our pilot data suggest that the GROW model to build women's leadership in GH is promising. GROW strategies continue to evolve as we recognize, build up, and realize the potential for women's leadership in GH, inclusive of all women in this field. Our team is surveying masters-of-public-health and mid-career fellows alumni to assess, using the GROW model, (1) the human, economic, and social resources that men and women received during their usual training and (2) the associations of these resources with the measures of career-related intrinsic and instrumental agency and with acquiring a leadership position in GH. This survey will enable us to select additional content to further the leadership capabilities of women in GH. We expect that post-graduate leadership training and on-going career mentoring will be a promising supplemental strategy. If the survey findings corroborate our expectations, we will design a supplemental program and conduct a randomized-controlled trial to compare the empowerment processes and career trajectories of women graduates randomly selected for the program, v. women graduates randomly selected for usual training only and all male graduates in the same cohorts who receive usual training. A favorable causal impact of the program would guide best practices for all Departments of Global Health to modify and to supplement their graduate curricula in ways shown causally to enhance women's leadership in GH.

Women's under-representation in global health leadership

Women are under-represented in leadership in global health (GH) across academic, governmental, and non-governmental institutions [Reference Barry1–Reference Downs4]. Across 191 countries, only 51 have a woman minister of health [Reference Magar5]. At Emory University, 91% of undergraduate minors and 84% of masters students in GH are women; yet, 75% of full professors (31 of 41) and 75% (six of eight) of named professors in GH are men. Women, including women of color, sexual minority women, indigenous women, other minority women groups, and women from lower income countries, remain disproportionately under-represented in leadership positions [6]. Women from different backgrounds face disparate barriers to leadership, which must be overcome to support the leadership potential of all women in GH [Reference Bowleg7].

Rationale for women's leadership in GH

Women's representation in GH leadership matters on the simple grounds of justice. Empirically, women make up 50% of the world's population, bear the unique burden of certain causes of death [Reference Alkema8], experience more years than men of life lost due to disability [Reference Vos9], comprise at least two-thirds of the GH workforce [Reference Magar5], and provide disproportionate unpaid care for the sick [Reference Magar5, Reference Berg and Woods10]. Women contribute around US$3 trillion to GH care, but nearly half of this (2.4% of global gross domestic product) is unpaid [Reference Dhatt2]. Given women's unique needs and contributions, women should have equal formal, descriptive, and substantive representation in the ranks of GH leadership. Equality in formal representation means having the same opportunities as men to participate in leadership, without discrimination based on gender or other intersecting identities. Equality in descriptive representation means that women are represented in equal numbers in positions of leadership. Equality in substantive representation means that women's interests are advocated in decision-making circles. Emerging evidence suggests that women need to be in leadership to have their interests represented [Reference Swers and Rouse11, Reference Wängnerud12].

Call to action and role of women's mentorship networks

The recent inaugural Women Leaders in Global Health (WLGH) conference established principles to advance women's leadership in GH. Recommended strategies included increasing the visibility of women by ensuring gender balance in all spheres of academia, nominating and promoting women for important committees and awards, advocacy for a culture that values work-life integration, eliminating gender gaps in pay, cultivating thought leadership among women professionals, addressing data gaps that mask persistent gender disparities in leadership, and promoting accountability. One strategic priority of the WLGH Initiative includes mentorship for women's leadership in GH.

GROW empowerment model for mentoring women leaders in global health

Given this ambitious agenda, models for mentorship are needed to position women for leadership in GH [Reference Talib and Barry3, Reference Downs4]. Mentorship can be a powerful tool to enhance the capabilities of individual women and to strengthen their collective capabilities to advance in the ranks. Our focus on mentoring to enhance capabilities differs from the typical psychosocial and professional outcomes that feature in the mentoring literature [Reference Hopwood13, Reference Dominguez14]. Enhancing individual and collective capabilities are essential to empower women for leadership in GH.

Here, we describe the theory of change and present pilot data for the mentorship model, Global Research for Women (GROW). GROW is an interdisciplinary, global initiative to catalyze empowerment, health, and freedom from violence for women and girls globally. Our guiding principle is that women's and girls’ empowerment is a pillar of sustainable development and is inextricably linked with their health and freedom from violence. Our strategic priorities are to advance scholarship, to cultivate leadership, and to generate dialogue that catalyzes social change through evidence-based policies, programs, and collective action for women's and girls’ empowerment.

Inclusive with all women and with men, the GROW mentorship model is adapted from a theory for women's empowerment developed by feminist economist, Naila Kabeer [Reference Kabeer15]. We define women's empowerment in GH as the process by which women acquire new human, economic, and social resources, which enable them to exercise agency, or the capacity to make strategic life choices to enhance their professional development in a context in which these capabilities were once denied. Below, we describe the components of this empowerment-based mentorship model to advance women's careers in GH (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. GROW empowerment model for mentorship and the advancement of women's leadership in global health.

Expanding human resources involves advanced theoretical and methodological training enabling scholars to acquire new knowledge and skills in subfields of GH; opportunities to lead and to co-author publications with our global network of affiliates; in-country practicums to build field experience; guidance on how to build effective teams for research, practice, or advocacy; discussions on emotional intelligence, including skills to negotiate on one's own behalf and to manage professional conflicts; and training on ethical principles for robust work in GH.

Investing economic resources includes advocacy for undergraduate, graduate, and post-graduate scholarships; recommendations for prominent internal and external fellowships, awards, and positions; mentorship on grant writing; opportunities to participate on externally funded team projects at all stages of career; and financial support to attend and to present at professional conferences.

Expanding social resources includes integration into interdisciplinary, project-based teams and peer groups to build collaborations; exposure to formal and informal professional networks; opportunities to attend professional conferences; introductions to professionals with similar career interests; and in-country internships to deepen global networks. Social resources also include the amplification of accomplishments via the media, including press releases, webinars, newsletters (http://www.growemory.org/archives), blogs (http://www.growemory.org/growblog), and social-media posts.

Agency is an intermediate outcome that may arise from the above enabling resources. Agency encompasses an intrinsic belief in one's capabilities, the strategic enactment of one's aspirations or preferences, and the collective action of women to advance women's leadership in GH. Intrinsic agency, or power within, entails the development of self-confidence, self-efficacy, and a critical awareness of one's professional worth and potential contributions. Instrumental agency, or power to, entails the enactment of strategic, or meaningful, decisions that advance one's career. Collective agency, or power with, entails a group's shared belief in its joint capabilities to organize and to execute mutually agreed actions for shared achievements. More than the sum of individual agencies, collective agency emerges from the interactive, coordinated, and synergistic dynamics of the group [Reference Bandura16]. Intrinsic and instrumental agency, as individual-level outcomes of mentoring, are rarely examined in mentoring models [Reference Hopwood13, Reference O'Meara17]. Collective agency has never been conceptualized or measured as an outcome of network-based models for mentoring. Through these pathways, GROW leverages the achievements of women leaders in GH to benefit women at all career stages.

An overarching theme of GROW is feminist praxis. Research documenting the inequalities, injustices, and violence faced by women and girls, and advocacy for women's equality, has been met with scrutiny, and even backlash [Reference Dragiewicz and Mann18]. GROW trains scholars to develop new theory and to apply rigorous methods, producing exceptional evidence to meet this resistance and to inform debates that advance women's interests. GROW's mission to empower early career professionals to produce scholarship of exceptional quality necessitates robust, feminist approaches to the design, implementation, analysis, and dissemination of research [19]. Mentorship from senior GROW affiliates on feminist ethical guidelines enables scholars to balance participant autonomy and safety in each study of empowerment and violence. GROW's networks provide opportunities for training on disciplinary standards within this specialized field.

Testimonials from GROW mentees

In Table 1, we present qualitative testimonials from graduates who received a pilot implementation of GROW since 2015. Qualitative evidence suggests that the focus on empowerment is attractive and capability enhancing. Trainees highlight the relevance of an interdisciplinary network supporting mutual growth, and rigorous research undergirded by a shared commitment to improve collectively the lives of women and girls. Excerpts from testimonials contextualize the capability-enhancing benefits realized by graduates mentored using the GROW framework. These testimonials reveal how GROW mentees have benefitted from the resources provided and the enhanced agency cultivated to advance their careers in GH. More information about the GROW network, access to scientific resources, and testimonials of the capability-enhancing benefits of GROW can be found at http://growemory.org/.

Table 1. Testimonials of the impact of GROW mentorship on the capabilities for leadership in global health

Excerpts include testimonies from women and one man mentee of GROW.

Next steps

Our pilot data suggest that the GROW model to build women's leadership in GH is promising. GROW strategies continue to evolve as we recognize, build up, and realize the potential for women's leadership in GH, inclusive of all women in this field. Our team is surveying masters-of-public-health and mid-career fellows alumni to assess, using the GROW model, (1) the human, economic, and social resources that men and women received during their usual training and (2) the associations of these resources with the measures of career-related intrinsic and instrumental agency and with acquiring a leadership position in GH. This survey will enable us to select additional content to further the leadership capabilities of women in GH. We expect that post-graduate leadership training and on-going career mentoring will be a promising supplemental strategy. If the survey findings corroborate our expectations, we will design a supplemental program and conduct a randomized-controlled trial to compare the empowerment processes and career trajectories of women graduates randomly selected for the program, v. women graduates randomly selected for usual training only and all male graduates in the same cohorts who receive usual training. A favorable causal impact of the program would guide best practices for all Departments of Global Health to modify and to supplement their graduate curricula in ways shown causally to enhance women's leadership in GH.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Michelle Lampl, Director of the Center for the Study of Human Health, and Ms. Agnes Mackintosh, Associate Director of Program Innovations and Development at the Center for the Study of Human Health, for providing data on the gender distribution of undergraduate minors in Global Health at Emory University.