I. Introduction

In a recent decision, the Human Rights Committee (HRC), the United Nations (UN) treaty body that monitors the implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), established that Australia had violated the rights of Torres Strait Islanders to enjoy their culture and family life (HRC 2022). This landmark decision followed a complaint filed by eight Australian nationals and six of their children, Indigenous inhabitants of four small islands in Australia’s Torres Strait region. They claimed their rights had been violated by Australia’s failure to adapt to climate change by upgrading the island’s sea walls and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The HRC set a precedent for those most vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change to hold their governments accountable for climate impacts under international human rights law.

Both the complaint and the decision would not have been possible without a normative framework under international human rights law on the relationship between climate change and fundamental human rights. This framework, frequently referred to in the decision, is General Comment no. 36, an interpretation adopted by the HRC in 2018 on the obligations of states parties under Art. 6, the right to life (HRC 2019: para 62). The committee established that the right to life also includes the right of individuals to enjoy a life free from acts or omissions that would cause their unnatural or premature death (HRC 2019: para 3). Legally non-binding and established as a tool to clarify obligations without the need for consent from states parties, it is striking that the treaty body has turned to General Comments to make such a significant contribution to the development of human rights. However, this example from the HRC is not the only case of treaty bodies shaping human rights law – going well beyond their core monitoring mandate.

We address this phenomenon by making a twofold argument in this article: first, we argue that treaty bodies use General Comments to informally shape international law. In drafting and adopting General Comments, they deliberately act as human rights law-makers, knowing that international and domestic institutions, other organizations and experts in their network will subsequently cite, reference, implement and further develop such instruments. Second, we argue that treaty bodies do not just rely on their network once they have adopted their outcome, but that the experts’ personal network also shapes the drafting process of such General Comments.

This argument for UN human rights treaty bodies as law-makers, rather than mere monitoring bodies, follows from a broader trend in scholarship and practice to recognize their agency (Hofferberth et al. Reference Hofferberth, Lambach, Koch, Holzscheiter, Deloffre, Reiners and Ronit2022; Reiners Reference Reiners2022; Sandholtz Reference Sandholtz2021; Ulfstein Reference Ulfstein, Liivoja and Petman2014). While often criticized as paper-tigers (Cassidy Reference Cassidy2008), recent research has highlighted their expert authority (Carraro Reference Carraro2019a, Reference Carraro2019b) and shown how they improve the implementation of and compliance with human rights norms (de Búrca Reference de Búrca2021; Comstock Reference Comstock2021; Creamer and Simmons Reference Creamer and Simmons2019, Reference Creamer and Simmons2020; see also Zvobgo and Graham Reference Zvobgo and Graham2020). The activism of treaty body members to address legal challenges in human rights is also observed in other international legal institutions (Çalı and Demir-Gürsel Reference Çalı and Demir-Gürsel2021; Malarino Reference Malarino2012; Stiansen and Voeten Reference Stiansen and Voeten2020). However, treaty bodies are not judicial institutions, and their members are not formally authorized to issue treaty interpretations. Despite their difference from other instruments of international law in terms of their drafting process and legal nature, Ando (Reference Ando and Wolfrum2012: para 41) argues that General Comments ‘tend to have quasi-legislative character’. Formal approaches to law-making and delegated authority cannot explain their adoption and influence in the absence of a legally binding nature and regularized decision-making procedures, effectively omitting the role of states as the primary law-making actors in world politics. This delegation gap is not mitigated by the drafting process, in which the expert body alone – devoid of intergovernmental influences beyond mere consultation – decides on the adoption of General Comments. Although it is precisely for this reason that states often contest them, General Comments can become influential instruments for norm development, and informal and formal decisions in human rights, as shown by the recent Australian case. We argue that we can only understand the drafting, content and influence of General Comments as law-making instruments if we conceptualize human rights treaty bodies as expert committees with open boundaries, embedded in broader professional networks.

In this article, we build on recent scholarship on informal law-making, expert authority and the influence of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) on decision-making in international organizations to better understand the horizontal and participatory processes of law-making by human rights treaty bodies. We identify three conditions that help explain the adoption of General Comments. First, treaty body members facing new challenges or normative ambiguities in human rights law seek outside counsel to overcome their scarce resources and – compared with judges in formal courts – limited (judicial) authority. Second, outside collaborators have the expertise and provide the treaty body with information that helps to better assess legal needs in local and global contexts. Third, treaty body members and outside collaborators join forces in a common project that can then help to fill the identified gaps in human rights law.

This framework advances scholarship on the complex processes of informal law-making by making three major contributions: First, by introducing a novel framework for analysing the adoption of General Comments, we advance the understanding of law-making by quasi-judicial and non-judicial actors that have been sidelined in both IR and IL scholarship (Pollack Reference Pollack, Romano, Alter and Avgerou2014: 384). We show how these actors continue to develop human rights when states shy away from law-making even under social pressure (Mantilla Reference Mantilla2020) and the salience of new issues (Rosert Reference Rosert2019a, Reference Rosert2019b). Second, by zooming in on law-making below the surface of formal treaty making (Krisch and Yildiz Reference Krisch and Yildiz2021), we contribute to a better understanding of the role of non-state actors in influencing law-making and standard-setting through transnational networks (Kortendiek Reference Kortendiek2021; Turkelli, Vandenhole, and Vandenbogaerde Reference Turkelli, Vandenhole and Vandenbogaerde2013), even when treatymaking stagnates, as it has for decades in the case of international criminal law (Berlin Reference Berlin2020). Third, this is important for answering the question of ‘who governs’ in world politics more broadly (Hofferberth et al. Reference Hofferberth, Lambach, Koch, Holzscheiter, Deloffre, Reiners and Ronit2022), and it shows how law-making can also be based on expert authority – even in the absence of formal delegation (Liese et al. Reference Liese, Herold, Feil and Busch2021).

To illustrate our argument and its contributions to scholarship in international relations (IR) and international law (IL), we apply the framework to two cases that differ in rights groups, the nature of the underlying treaty and the reasons for treaty body action: the right to water, adopted by the Committee for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) in General Comment no. 15 in 2002 (Reiners Reference Reiners2022); and the defence of the torture prohibition adopted by the Committee against Torture (CmAT) in General Comment no. 2 in 2008 (Lesch Reference Lesch2023). The right to water amends a general treaty in the area of economic, social and cultural rights, responding to decades of debates but a stalemate in formal progress (Bulto Reference Bulto2011). General Comment no. 2 specifies and clarifies a specialized and precise treaty in civil and political rights, the Convention against Torture (CAT), responding to severe challenges in light of counterterrorism campaigns in the 1990s and early 2000s (Liese Reference Liese2009; Zimmermann et al. Reference Zimmermann, Deitelhoff, Lesch, Arcudi and Peez2023: Ch 2). Within the scope of human rights research methods (Andreassen, Sano and McInerney-Lankford Reference Andreassen, Sano and McInerney-Lankford2018), we use a process-tracing approach (Checkel Reference Checkel, Bennett and Checkel2015; Guzzini Reference Guzzini2017; Salehi Reference Salehi2022; van Meegdenburg Reference van Meegdenburg, Mello and Ostermann2023) to understand the process that led from a specific human rights challenge to the adoption of a General Comment addressing this issue. Based on meeting minutes, archival materials and expert interviews, we unpack the drafting history of both General Comments and provide empirical evidence for the mechanisms in our framework.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. We begin by demonstrating that all human rights treaty bodies are increasingly using General Comments – often with an explicit law-making purpose – and summarize the central, mostly legal, scholarly debate about them. We then review the law-making literature as well as network approaches to international organizations and expert bodies. Against this background, we present our three-step theoretical framework for tracing how human rights treaty bodies engage in law-making and adopt General Comments. We illustrate this framework with two case studies on how the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Committee Against Torture each draft General Comments. We conclude by discussing our comparative findings and outlining avenues for further research.

II. Beyond human rights monitoring: Law-making through General Comments

All international human rights treaties have established expert committees to monitor the implementation of and compliance with the norms they codify. Today, nine such bodies exist.Footnote 1 They vary in size from ten to 23 members, who are elected by the states parties to the treaties. Once elected, they are expected to act independently of national and institutional interests in their individual capacities (Carraro Reference Carraro2019a: 826; Reiners Reference Reiners2022: 29–30). These bodies differ from many other international institutions in that they are purely expert committees that are not subject to an immediate intergovernmental oversight body that could be used to control agency slack (Nielson and Tierney Reference Nielson and Tierney2003). There is growing scholarly evidence for a more activist role of treaty bodies within their monitoring mandate (Davidson Reference Davidson2022; Reiners Reference Reiners2022). Moreover, their unique institutional design has allowed them to go even beyond their monitoring mandate.

Human rights treaty bodies monitor compliance with treaty norms through the self-reporting procedure, the individual and interstate complaint mechanism as well as (in some committees) through on-site inquiries (Connors Reference Connors, Moeckli, Shah, Sivakumaran and Harris2018). Under the self-reporting procedure, which is mandatory for all states parties, committees evaluate state reports and shadow reports submitted by NGOs in order to issue ‘concluding observations and recommendations’ (Creamer and Simmons Reference Creamer and Simmons2020: 16–17). Although it is not legally binding, there is growing evidence that self-reporting to treaty bodies improves compliance (Creamer and Simmons Reference Creamer and Simmons2019, Reference Creamer and Simmons2020; Comstock Reference Comstock2021). Individual and interstate complaint mechanisms are subject to opt-in or opt-out by states parties at the time of treaty ratification. While interstate complaints have only been lodged with one treaty body, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (Tamada Reference Tamada2021), the individual complaints are a frequent and important mechanism for individuals seeking redress, with the treaty bodies issuing quasi-judicial (formally non-binding) decisions (Ulfstein Reference Ulfstein, Keller and Ulfstein2012: 92–93; see also Shikhelman Reference Shikhelman2019; Ullmann and von Staden Reference Ullmann and von Staden2020).Footnote 2

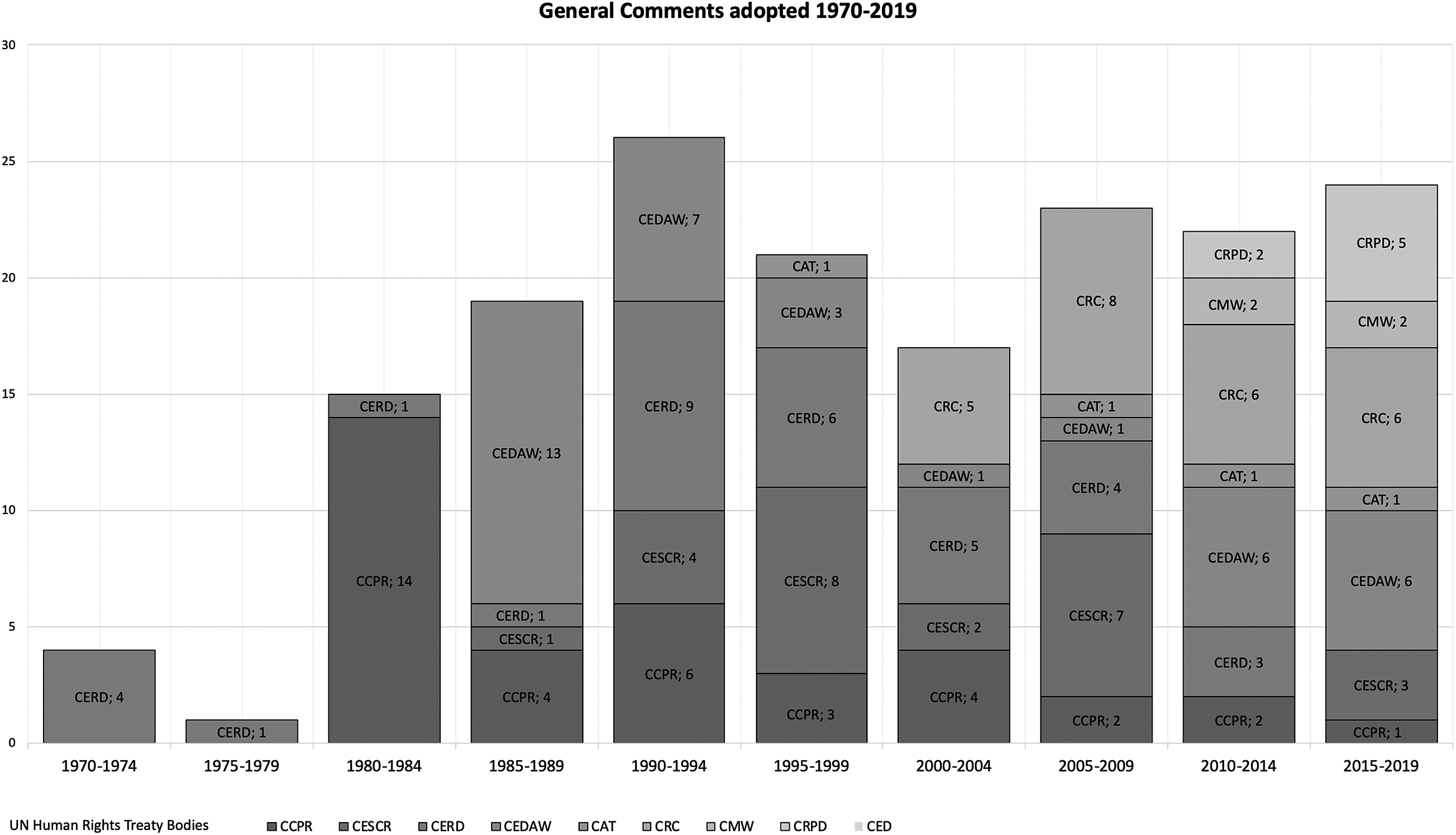

Despite the lack of formal authority, treaty bodies have also begun to act more explicitly as law-makers, sometimes going beyond the original treaties. All treaty bodies have increasingly instrumentalized their mandate to issue General Comments or General Recommendations – originally intended as part of the self-reporting process. Since the establishment of the first human rights treaty bodies, the number of General Comments has increased steadily (Figure 1). By 2020, they had passed 172 General Comments. Once adopted, many become anchors in human rights discourse, the practice of other international organizations as well as regional and national judiciaries (Barkholdt and Reiners Reference Barkholdt and Reiners2019; Creamer and Simmons Reference Creamer and Simmons2020: 33; McCall-Smith Reference McCall-Smith, Lagoutte, Gammeltoft-Hansen and Cerone2016). In practice, they have become ‘a means by which a UN human rights expert committee distills its considered views on an issue which arises out of the provisions of the treaty whose implementation it supervises’ (Alston Reference Alston, De Chazournes and Gowlland-Debbas2001: 764). In other words, they are generally addressed to all states parties to the respective treaties and comment on questions of interpretation, compliance and implementation. As ‘authoritative interpretations’ of a treaty (Reiners Reference Reiners2022: 24–25), they either reflect and summarize the views already established by the treaty body (Rodley Reference Rodley and Shelton2013: 631) or they translate their existing jurisprudence into new or modified interpretations of the treaties they oversee (Lesch Reference Lesch2023).

Figure 1 Number of General Comments adopted between 1970 and 2019 by the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), Committee on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR), Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), Committee Against Torture (CAT), Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC), Committee on Migrant Workers (CMW) and Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRDP). Own compilation.

General Comments are law-making instruments because, despite their non-binding nature, they shape the interpretation, application and development of international human rights law. They are not only important points of reference for the treaty bodies themselves (Rodley Reference Rodley and Shelton2013: 632), but they are also cited by other international legal institutions and in domestic legal proceedings (Kanetake Reference Kanetake2018). This is surprising because they are not explicitly codified in the human rights treaties, and the decision about when they are needed is left to the committee. From a principal–agent perspective, they challenge the chain of delegated authority provided by the states parties as they are adopted by the committee – without the direct consent of states. Therefore, their legal nature is disputed from an international law perspective (Alston Reference Alston, De Chazournes and Gowlland-Debbas2001: 764; Keller and Grover Reference Keller, Grover, Keller and Ulfstein2012: 128). Moreover, human rights treaty bodies are under severe budgetary pressure and time constraints to devote their energies to the drafting of General Comments. This is also reflected in the fact that the drafting of General Comments usually follows an ad hoc approach without formalized procedures (Keller and Grover Reference Keller, Grover, Keller and Ulfstein2012: 168). Typically, treaty bodies assign a rapporteur to draft a General Comment and allow them a certain degree of discretion. The draft is usually shared with states parties and civil society actors, who are also invited to participate in the consultation. After a final reading, the committee adopts the General Comment (Rodley Reference Rodley and Shelton2013: 632).

The legal ambiguities and informality, the ad hoc approach and non-regularized procedures, combined with the close ties between treaty body members and civil society actors, are key variables in explaining the assertive role of human rights treaty bodies as law-makers. In the next section, we review the relevant literature on law-making and transnational networks as a basis for our theoretical framework.

III. Expanding the playing field: Law-making by judicial actors and informal networks

Law-making is the traditional domain of sovereign states, which formally legalize norms in international treaties (Abbott et al. Reference Abbott, Keohane, Moravcsik, Slaughter and Snidal2000). The major humanitarian law and human rights treaties are the result of formal codification processes. In recent decades, however, formal law-making efforts have rarely been successful (Pauwelyn, Wessel and Wouters Reference Pauwelyn, Wessel and Wouters2014). Overall, international law in various issue areas is often depicted as being in a state of crisis (Lesch and Marxsen Reference Lesch and Marxsen2023; Krieger and Liese Reference Krieger and Liese2023). At the same time, law-making has increasingly moved away from such a traditional, consensual approach (Krisch Reference Krisch2014). The literature on judicial law-making shows that – at least formally authorized – judicial institutions act as law-makers in the judgments, decisions, and advisory opinions they issue (von Bogdandy and Venzke Reference von Bogdandy, Venzke, von Bogdandy and Venzke2012), especially when they set precedents for the application and development of international law (von Bogdandy and Venzke Reference von Bogdandy and Venzke2014). In this literature, however, law-making is still conceived as based on a formal mandate and following established chains of delegation. Going a step further, legal scholars have also demonstrated the growing influence of informal law-making approaches without a direct mandate (Block-Lieb and Halliday Reference Block-Lieb and Halliday2017; Brölmann and Radi Reference Brölmann and Radi2016; Pauwelyn, Wessel and Wouters Reference Pauwelyn, Wessel and Wouters2013; Venzke Reference Venzke2012). So far, this literature is interested mainly in the substance of law-making and less in the process. Both literatures have yet to fully appreciate the role of expert committees and quasi-judicial bodies in general, and of human rights treaty bodies in particular, as relevant actors in the interpretation and making of international law (Lesch Reference Lesch2023; Reiners Reference Reiners2022).

In IR, the processes that lead to norm emergence and law-making are well studied. In particular, scholars have demonstrated the transnational dimension of law-making, which is critically shaped by norm entrepreneurs (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998), social pressure (Mantilla Reference Mantilla2020), and salience (Rosert Reference Rosert2019b). Others analyse decision-making in intergovernmental entities that shape global standards (Gehring and Dörfler Reference Gehring and Dörfler2013; Gifkins Reference Gifkins2021), the influence of IO bureaucracies (Weinlich Reference Weinlich2014), practice-based standard-setting between the field and headquarters (Kortendiek Reference Kortendiek2021) and the role of expertise as a tool for IO’s mission creep in standard-setting (Littoz-Monnet Reference Littoz-Monnet2017). Only few studies have looked at how individuals influence law-making in international organizations (Bode Reference Bode2015), and how judges of international courts change the law in practice (Stappert Reference Stappert2020). This literature has begun to unpack the processes within expert bodies and the role of their networks in shaping decision-making and law-making processes (Davidson Reference Davidson2022; Lesch Reference Lesch2023; Reiners Reference Reiners2022). While research on international organizations (Barnett and Finnemore Reference Barnett and Finnemore2004) and expert committees (Carraro Reference Carraro2019a) has demonstrated that international civil servants and independent experts enjoy autonomy, there has been less interest in how they make use of this autonomy – particularly across organizational boundaries and within professional networks (see Block-Lieb and Halliday Reference Block-Lieb and Halliday2017: 33; Kortendiek Reference Kortendiek2021: 325–26). In human rights, such a perspective is more than pertinent because formal law-making is stagnating; at the same time, multiple stakeholders – including civil society, expert committees and domestic courts – can, and increasingly do, push back against contestation and norm violations (Wiener Reference Wiener2018: 10).

Building on and developing this scholarship further, the next section outlines a framework that advances our understanding of informal law-making and norm development by human rights treaty bodies, focusing on the non-governmental nature of treaty bodies and the interactions of their members with professional networks.

IV. Law-making by human rights treaty bodies: A framework for analysis

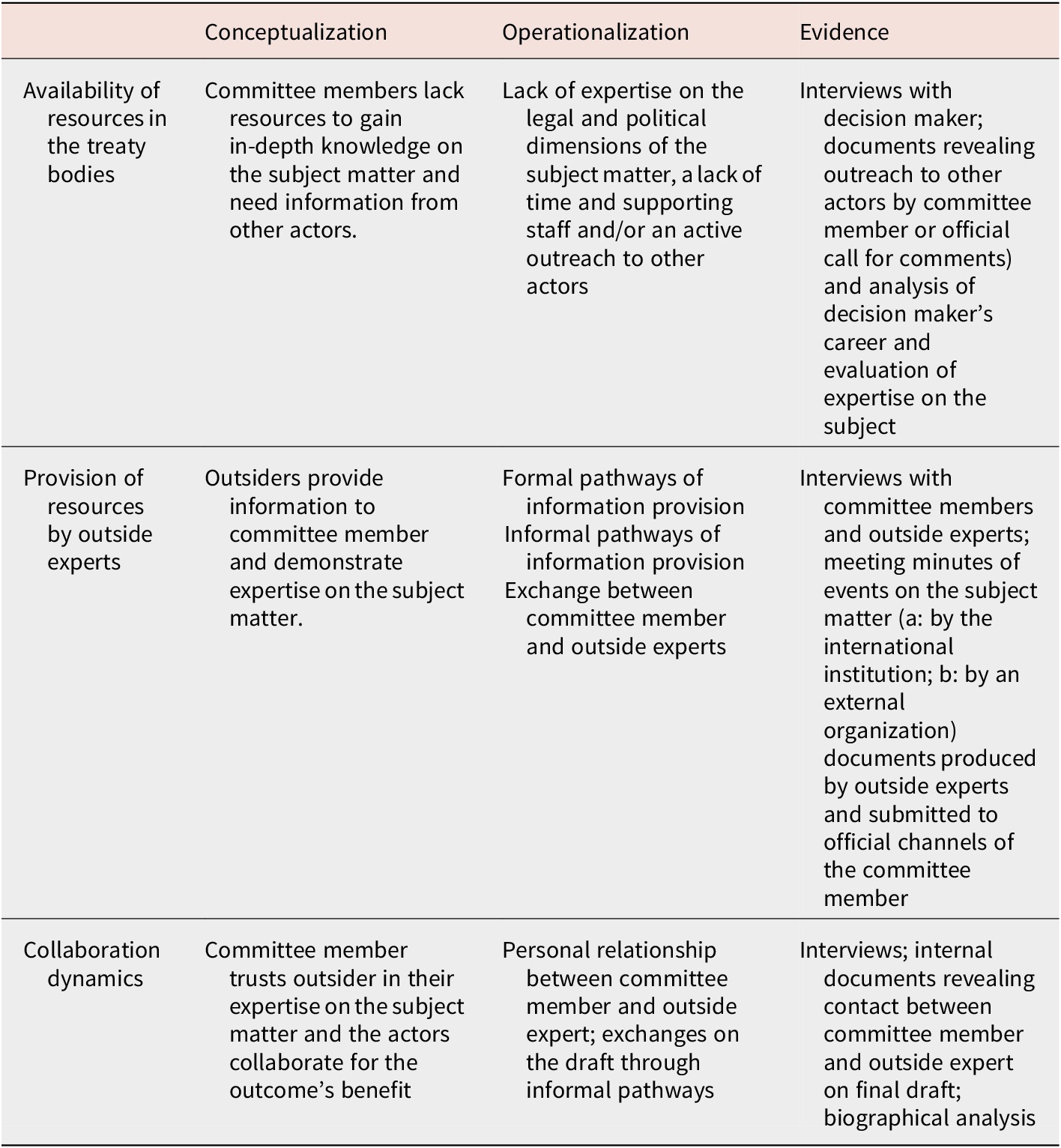

Informal law-making processes rely on micro processes within the networks of the relevant actors (Block-Lieb and Halliday Reference Block-Lieb and Halliday2017: 10). Thus, human rights treaty bodies are not unitary actors, but rather diverse bodies composed of their individual expert members embedded in professional networks that transcend institutional boundaries. As these experts operate under various constraints, they rely heavily on interaction with civil society actors as we will show, not only with regard to their monitoring task, but also when they engage in law-making. As summarized in Table 1, we propose to analyse the process of treaty body law-making in three steps. In the first step, we focus on the availability of resources for the treaty body. The lack of resources then turns our attention in the second step to the external collaborators, and their strategies and motives for providing resources to the independent experts. The third step focuses on observing the dynamics between treaty body members and outside collaborators. Analysing these three steps will provide a more complete picture of how treaty bodies expand their mandates and adopt General Comments that develop human rights and make international law. In all three steps (see Table 1), we assume that the drafting of law-making General Comments is more likely when treaty body members invite external expertise into the process. This approach is also central to the legitimization of General Comments as acts of law-making in the broader human rights community.

Table 1. Framework for analysing law-making by human rights treaty bodies

Step 1: Resources in the UN treaty bodies and the demand for outside expertise

In expert committees, individual members sometimes face conflicting political demands from principals and their social environment (Block-Lieb and Halliday Reference Block-Lieb and Halliday2017). Particularly in contested environments, this can influence issue selection when committees and other stakeholder demand a response to challenges or unaddressed issues. Ideally, their decision-making process takes these demands into account when developing international law. This increases the likelihood that the results will be implemented and complied with. However, they often lack the resources to effectively adjudicate a matter, and therefore recruit or empower other actors to assist in the process (Lake and McCubbins Reference Lake, McCubbins, Hawkins, Lake, Nielson and Tierney2006). There are many reasons why the decision-makers themselves may lack the resources – such as additional time, money, expertise and/or connections – to undertake the research and work required to produce substantive interpretations. Treaty bodies are composed of independent experts who are not formally employed by the organization, and whose compensation – calculated on a per diem basis – is directly related to their time in attendance at official committee meetings.

This arrangement typically leads to a lack of resources in two ways: in the form of time constraints, as committee members often continue with their main jobs or other commitments and therefore do not have the time to prepare rigorously, and in the form of a lack of information on domestic implementation, which includes costs for travel and participation in workshops and conferences. At the same time, the resources of the institution’s bureaucracy play a key role in effectively supporting to such bodies (Patz and Goetz Reference Patz and Goetz2019). Not all secretariats of monitoring bodies are adequately staffed for the workload associated with law-making and lack the necessary personnel to take on tasks beyond, for example, organizing meetings, assisting states parties in their reporting and supporting the committee members. Faced with this lack of resources, committee members turn to external actors for two related reasons: they have a functional demand for expert knowledge to make their decisions and/or they rely on their expertise to legitimize their decisions (see Boswell Reference Boswell and Littoz-Monnet2017: 19). However, in their status as arbiters of the external sources that are ultimately consulted, committee members can act as gatekeepers for external influence on law-making. With the decision to rely on external expertise, or even involve external actors in the process, their knowledge is likely to influence the substance of the law-making process, potentially even pushing law-making initiatives beyond their original goals.

Step 2: Provision of resources through outside collaborators

Through their networks, treaty body members can draw on different types of resources: material, in the form of money and data; or ideal, in the form of expertise and knowledge (Betsill and Corell Reference Betsill and Corell2010; Block-Lieb and Halliday Reference Block-Lieb and Halliday2017; Squatrito Reference Squatrito2016). In practice, support is typically encouraged and enabled by the international institution itself, whether through an open call for comments on a first draft of an interpretation, or through multi-stakeholder events, such as days of general discussion on the topic. However, not all input received at such events or through public calls can be considered by decision-makers facing resource constraints.

The salient determinant in the selection of input for law-making lies in expert knowledge, not necessarily in what scholars call the ‘attractiveness of their ideas and values’ (Charnovitz Reference Charnovitz2006: 348). Experts are endowed with a more neutral competence ‘to make (and communicate) assessments, judgements, and recommendations based on their knowledge’ (Liese et al. Reference Liese, Herold, Feil and Busch2021: 356), as opposed to communicating advocacy claims. Ideas need to be translated into specific legal obligations, and expertise needs to be highly specialized (see also Littoz-Monnet Reference Littoz-Monnet2020). Tangible support can also play a role at this stage. Deciding on legal standards sometimes requires spending money that the international institution cannot provide. For example, in the area of human rights and labour standards, field trips are often needed to observe local implementation challenges, and research may require additional resources to reflect universal standards. During this phase, meetings outside of the institution are often organized by transnational actors, such as NGOs, political foundations or other networks. In these meetings, actors can test the acceptability of the scope of a later decision and calculate the input of their resources accordingly. In addition, these meetings provide an important opportunity to develop or intensify relationships with the decision-making body. The nature of the interaction can range from low-key, brown-envelope diplomacy to meetings outside of the official sessions to explicit requests for information. However, while we believe the provision of resources is important for the participation of outside experts in the law-making process, a resource exchange logic does not fully explain transnational influence in treaty body decision-making.

Step 3: Dynamics in collaboration

Finally, relationships between committee members and external collaborators help to bring norms into an institution (Anderson Reference Anderson2000). Public administration scholars have pointed to the strategic use of institutional connections in order to advance goals (Fleischer and Reiners Reference Fleischer and Reiners2021; Oliver Reference Oliver1991; Wiewel and Hunter Reference Wiewel and Hunter1985). Similar behaviour can be observed at the individual level, and personal networks become a key resource for influencing law-making. A trusting relationship increases the chances that external actors will not only provide input, but that it will eventually be taken into account. Analyses of influence in international law-making need to make these dynamics visible, which is methodologically and empirically challenging. A good starting point is to focus on the central decision-maker. We know from previous studies that the chair of a committee is particularly important as a gatekeeper (Elsig Reference Elsig2011). The operational logic here is simple: given the basic assumption – that outcomes will only be accepted by member states if they privilege international consensus – expert committees need to trust that an outside expert’s contribution in the process is reliable (see also Walker and Biedenkopf Reference Walker and Biedenkopf2020). A personal relationship can prove to be of paramount importance here, which in turn enables the process and the outcome to be influenced successfully.

Empirically, this relationship is formed during the drafting process, either externally, through a previous professional relationship outside the international institution (former colleagues, supervisors, students, etc.), or internally, through previous quality work experience directly within the international institution (e.g. former expert body or bureaucracy member). Personal relationships may further explain the motivation for individuals to invest time and other resources in the drafting process without officially receiving credit (e.g. not being named as a drafter and thus not being able to claim this role in their NGO’s annual reports or personal résumés). Outside collaborators are professionals who have a strong interest in the development of international law – also driven by contestation and backlash that they want to fend off. They accept that they are largely invisible in international law-making. Unlike the agenda-setting and assistance in compliance-monitoring roles, their activities are carried out largely unrecognized by the public. This may privilege actors who are less dependent on funding from sources that want to see their donations as having an impact and those who do not need to provide detailed accounts of their activities to their donors. The possession of resources, both material and ideal, is crucial to their participation in the drafting process – and ultimately to their influence.

Two illustrative case studies

The impact of General Comments varies, and their status in international law is contested because their adoption does not require the formal consent of states. Nevertheless, some of the treaty bodies’ interpretations have had a significant impact on the development of human rights and international law significantly despite a pushback from states. In this article, we focus on two such cases to illustrate our framework: General Comment no. 15 adopted by the CESCR in 2002, on the right to water; and General Comment no. 2 adopted by CmAT in 2008, on the applicatory scope of the torture prohibition. Both are cases of law-making by expert committees, but with different purposes: One General Comment has established a new right, the right to water under the ICESCR, and one has specified an existing treaty obligation, the non-derogability of the prohibition of torture under the CAT. The former thus effectively amends the body of rights covered by the original, rather broad, treaty and adds a new positive obligation. The latter advances the meaning of the original, more specific, treaty and its negative obligations. It constitutes a statement about what constitutes a violation of a treaty norm. While CECSR added an additional right to the field of economic and social rights, CAT clarified its interpretation of the Convention against Torture in a long-standing dispute. Despite these differences, both are important examples of treaty bodies law-making that advances the development of human rights. Following a process-tracing approach (Checkel Reference Checkel, Bennett and Checkel2015; Guzzini Reference Guzzini2017; van Meegdenburg Reference van Meegdenburg, Mello and Ostermann2023), both case studies are based primarily on official documents, interviews and secondary literature.

V. Making water a human right: General Comment no. 15 on ICESCR

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) was adopted in 1966 and entered into force ten years later. Unlike the right to food or the right to health, a human right to water for all was not included in the core human rights treaties (Riedel Reference Riedel, Riedel and Rothen2006). The absence of a right to water in international human rights law was puzzling to human rights scholars and practitioners (Cahill Reference Cahill2005; Thielbörger Reference Thielbörger2014). Despite long-standing debates, stagnation in its normative and legal development characterized international human rights law in the following decades (Reiners Reference Reiners2021). Only the treaties on women’s and children’s rights, adopted in 1979 and 1989, contain the term ‘water’ at all, but as a qualifier for the realization of other rights and in relation to vulnerable groups. Social pressure on states to recognize water as a human right was strong and advocacy efforts included NGOs, social movements and activists in the areas of human rights, development and environment (Simonson Reference Simonson2003). However, this pressure has not been sufficient to persuade states to act on this pressing gap in human rights law. The reasons identified for the stagnation of water as a human right are mainly related to unresolved issues of water and privatization (Baer Reference Baer2017; Langford Reference Langford2005; Moyo and Liebenberg Reference Moyo and Liebenberg2015). The provision of infrastructure for access to drinking water and the quality of its provision have turned water into a global commodity. Many states have outsourced the provision of water for drinking and sanitation purposes to corporations, subject to private payment for their services. Some governments fear that recognizing a universal human right to water would ultimately hold states accountable when services are not provided or not paid for.

To provide a brief timeline, the adoption of the General Comment in November 2022 followed a drafting process that took just a year (Reiners Reference Reiners2022: 66–93). However, this drafting process was preceded by decades of advocacy for the recognition of a right to water for all at the international level. As argued earlier, while social pressure was strong, states did not act to recognize water as a human right. Advocacy efforts were directed to the Geneva-based human rights treaty bodies (Reiners Reference Reiners2021). CESCR members were open to the idea because the ICESCR already recognized a right to an adequate standard of living (Art. 11), which included food, and a right to the highest attainable standard of health (Art. 12). Yet it was not until 2002 that the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CECSR) adopted General Comment No. 15 on the right to water, filling this gap in international human rights law. How did the CESCR make water a human right?

Lack of time and technical expertise

The resources available to the CESCR to draft this General Comment were limited for two reasons: a lack of time and technical expertise on water on the part of the committee; and sanitation-related aspects of health and living conditions. Time was scarce because the committee members are only paid a per diem for the meeting time in Geneva. This means that committee members return to their regular jobs after the meetings and these meetings do not include the drafting of General Comments. During the drafting process, the CESCR met three times a year, usually for two to three weeks.Footnote 3 These sessions were full of meetings on state reporting procedures. During this time, the committee also prepared or adopted General Comments on the topic of food (ECOSOC 1999a), education (ECOSOC 1999b), and health (ECOSOC 2000). An additional and time-sensitive drafting process on the right to water, to be completed before the International Year of Freshwater in 2003, was thus hardly manageable (Riedel Reference Riedel, Riedel and Rothen2006).

As far as technical expertise was concerned, no member of the committee at that time had technical expertise in the field of water, although the later rapporteur for the General Comment, a professor of international law, had knowledge of water law (Riedel Reference Riedel, Riedel and Rothen2006). The committee therefore needed external support for the technical aspects of the obligations of such a right in the drafting process.

Water and sanitation in development, health and privatization

In the case of General Comment No. 15, the resources required were expertise on the specificities of the ICESCR – for example, Article 11 on an adequate standard of living – and in-depth knowledge of the issues arising from ensuring access to water and sanitation in relation to economic, social and cultural human rights. Health-related dimensions, corresponding to Article 12 of the ICESCR, were of additional importance in drafting a strong General Comment on a human right to water. In the context of decades of advocacy confronting the limits of a rights-based approach to water in neoliberal economies, it was also necessary to consider how such economic arguments against a right to water could be countered in legal terms (Winkler Reference Winkler2014).

In this case, the external collaborator who formed the main drafting coalition was a legal officer from an NGO specializing in legal solutions to socio-economic challenges. On an informal level, the founder and director of the NGO approached the future rapporteur directly with the idea of preparing a General Comment on the right to water ready within the next year. Both had previous experience as colleagues, and the director himself knew that the later rapporteur and the committee were generally receptive to the idea. With the UN environment ripe for such a right to water, the committee member recognized a certain confluence of perfect timing to move forward and initiate the drafting process by volunteering as a rapporteur (Reiners Reference Reiners2022: 66–93).

On a formal level, the NGO director wrote an official letter to the chairperson of the CESCR, explicitly recognizing a window of opportunity for a human right to water, and thus an official appeal from civil society that the committee indeed considered.Footnote 4 The NGO had previously been involved in other drafting processes and was therefore aware of the formal legal aspects to be considered. This NGO formally approached the CESCR in writing with a proposal to draft and adopt such a General Comment before the 2003 International Year of Freshwater. Informally, the committee member, who later became the rapporteur, exchanged views with the officer on the basic outline. They agreed that they needed more health and development expertise. One outside collaborator who had been working with the main drafter – an expert on water and land issues, recently employed by a development aid organization, and notably with no experience in human rights work – joined the drafting group.Footnote 5 She was approached by the above-mentioned officer while discussing another project at a conference, and invited to contribute to the drafting of General Comment No. 15. They were joined by a WHO officer responsible for water-related projects at WHO. He met informally with the core drafting group, but also spoke about the need for the General Comment at the public discussion day in November 2002 (Reiners Reference Reiners2022: 66–93).

A small and efficient drafting group

Previous reflections on the drafting process point to the key role of external collaborators in enabling the treaty body to act as law-maker (e.g. Langford Reference Langford2006; Tully Reference Tully2005), yet the avenues for collaboration appear to be rather exclusive and taking place outside of formal meetings and venues. The actors involved in the drafting of this General Comment were remarkably few in number, and these individuals came together on the basis of their acquaintance through previous professional relationships. The legal officer’s NGO had already worked together with the CESCR, and in particular with the rapporteur, on the General Comment 12 on the right to food and was therefore known to the committee and he was present in Geneva. The rapporteur and the officer jointly discussed several drafts that they had prepared based on current discussions on the scope of the right to water. The rapporteur, as the group’s operating member of the treaty body, took into account the committee’s experience with states and their views as expressed in reports and during the dialogues. The NGO representative, as a legal expert on socioeconomic rights, was familiar with national court decisions on water issues. His autonomy in the drafting process was also reflected in the informal meetings held in the NGO’s offices to work on the draft. Since the final draft was only discussed once in public, and not published in advance, the expert committee also kept the circle of external contributors small (Reiners Reference Reiners2022: 66–93).

General Comment no. 15 provided the first normative framework in international human rights law for a right to water. However, not all the demands of the right’s advocates were successfully incorporated into General Comment No. 15. The committee did not include a right to sanitation, largely because members ‘did not believe there was sufficient international support in international law’ (Langford, Bartram and Roaf Reference Langford, Bartram, Roaf, Langford and Russell2017: 356). The CESCR took a bold decision to add a right to the covenant that was not included in the original treaty. This is the main reason why opposition to the General Comment immediately followed (Tully Reference Tully2005; US 2007). Indeed, the General Comment on the right to water was met with criticism from states parties and governments that had not even ratified the ICESCR. Governments and legal scholars accused the CESCR of overstepping its mandate and jeopardizing the credibility of the entire treaty body system. However, General Comment no. 15 by the CESCR provided a framework and served as a reference for advocacy work, policy and domestic court decisions (Langford and Russell Reference Langford and Russell2017). Only eight years later, the rights to water and sanitation were recognized by resolutions of the UN General Assembly and the Human Rights Council (UN General Assembly 2010).

VI. Defending the torture prohibition against contestation: General Comment no. 2 on CAT

The UN General Assembly adopted the Convention Against Torture (CAT) in 1984. While the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights had already codified the prohibition of torture as a non-derogable human right, CAT was intended to better implement the prohibition (Burgers and Danelius Reference Burgers and Danelius1988: 1). As a result, CAT is a precise human rights treaty that specifies state obligations to prohibit and prevent torture under a pre-existing human rights norm. This includes a definition of torture in Article 1, specifications of the scope of the prohibition – its non-derogability as well as the principle of non-refoulment – and several preventive measures regarding national legislation (Nowak, Birk and Monina Reference Nowak, Birk and Monina2019: 6–9). As such, CAT has a rather narrow mandate with prima facie precise obligations. This may be one of the reasons why CmAT has been ‘fairly reluctant’ to adopt General Comments (Nowak, Birk and Monina Reference Nowak, Birk and Monina2019: 528). To date, it has adopted four General Comments, still considerably fewer than the other treaty bodies (see Figure 1, above).

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the international torture prohibition was contested by Israel and the United States, which sought to justify their interrogation techniques in the fight against terrorism under CAT (Liese Reference Liese2009; Zimmermann et al. Reference Zimmermann, Deitelhoff, Lesch, Arcudi and Peez2023: Ch 2). This contestation did not go unchallenged by states (Schmidt and Sikkink Reference Schmidt and Sikkink2019: 109) and transnational litigation networks sought redress for torture victims in international, regional and national courts (Wiener Reference Wiener2018: 144–148). This contestation was also the central impetus for the committee to move forward with a second General Comment, beginning with a letter send out to all states parties clarifying that the prohibition of torture and ill-treatment ‘must be observed in all circumstances’ (CmAT 2002a: para 17). Before and after this letter, however, efforts to draft a second General Comment suffered several setbacks. This included failed attempts to establish productive collaboration between committee members and outside experts. Once these challenges were overcome, the drafting process was completed in November 2007. After three meetings of detailed discussion of the drafts, the Committee concluded the process in two sessions and formally adopted General Comment no. 2 (CmAT 2007b: para 57). General Comment no. 2 states that the ‘obligation to prevent ill-treatment in practice overlaps and is largely congruent with the obligation to prevent torture,’ including its non-derogability (CmAT 2008: para 3). It clarifies that this non-derogability also applies in the fight against terrorism and to states acting within and outside of their territory (CmAT 2008: paras 5, 7). Nigel Rodley (Reference Rodley2008: 356), then a member of the HRC, underlined that General Comment no. 2 was crucial because it clarified that torture was not ‘at the top end of a pyramid of pain and suffering’ and that the international prohibition applied to ill-treatment similarly, to everyone, at all times and everywhere. It was thus a crucial law-making effort by CmAT in response to growing contestation (Lesch Reference Lesch2023). It also clarified that domestic violence could constitute torture (Davidson Reference Davidson2022: 217–18). How was this law-making by CmAT possible?

Interpretative uncertainty and limited resources

At CmAT, resources are even more scarce than at other human rights treaty bodies, given that it is one of the smallest treaty bodies with only ten experts mandated to monitor compliance in today’s 173 states parties. Committees with more members can more easily delegate drafting tasks to subcommittees or rapporteurs. Moreover, CmAT experts were unable to reach a consensus on how and on what issue to use General Comments (Kelly Reference Kelly2009: 791). During the debates on a second General Comment, socialization in different legal systems came to the fore, with members coming from a common law tradition being more sceptical (e.g. CmAT 2002b: para 73; CmAT 2006a: paras 10, 24). Moreover, CmAT differs from other committees in that its experts have different professional backgrounds, not only legal, which may increase the demand for legal expertise. In sum, the lack of resources, only limited agreement on the core issues and interpretive uncertainty have long characterized CmAT’s reluctance to draft additional General Comments. As a result, despite the need to clarify treaty obligations, CmAT has only made limited use of this instrument, not least in the face of challenges and non-compliance. However, states parties (e.g. in CmAT 2005) as well as civil society have called on the committee ‘to take advantage of this opportunity’ (Evans Reference Evans2002: 367).

In 2000, outside experts actively sought to work with the committee members to assist them in drafting a General Comment on Article 1, CAT and the definition of torture. The Association for the Prevention of Torture (APT) had made such a proposal in November 2000 at an event organized by APT and attended by many members of CmAT. However, there was no follow-up by the Committee at that time, and the proposal remained at ‘an embryonic stage’ (Evans Reference Evans2002: 368, n 18). Although the Committee discussed several proposals, none of them really took off (CmAT 2000a: paras 11-13; CmAT 2000b: para 12). After the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, CmAT chairman Peter Burns considered the idea of a General Comment on Article 2 in the context of counter-terrorism (CmAT 2001: paras 49, 50). This initiative did not bear any fruit until 2006. For the time being, it only resulted in a letter to all states parties clarifying for the first time that the prohibition of torture and ill-treatment was non-derogable (CmAT 2002a: para 17). CmAT’s lack of response to early proposals for a second General Comment and the lack of follow-up to the 2001 letter further indicate the limited resources available to the committee to engage in a drafting process. Even when the drafting process was underway in 2004, time constraints were still a major challenge to its completion.

Torture, ill-treatment and unproductive collaboration between CmAT and NGOs

As noted above, the need for a second General Comment on CAT arose from interpretive uncertainty regarding the distinction between Art 1, CAT on torture and Art 16, CAT on ill-treatment. The question of whether torture has actually occurred and whether states sufficiently implement the definition of torture are among the most contentious issues before the committee (Lesch Reference Lesch2023). Following the proposals for a General Comment on Article 1, a CmAT member tabled another proposal in 2002 (CmAT 2002b: para 69). However, it was strongly rejected by committee member Felice Gaer because an earlier ‘proposal had caused consternation among the NGOs who feared that a revised definition would either water down the definition of torture or narrow its focus’ (CmAT 2002b: para 71). This put an end to CmAT’s efforts to comment on Article 1 based on the reactions of outside experts. The next step in the drafting history of a second General Comment was the individual foray of committee member Marino Menéndez, who submitted a first draft on Article 2 during the 31st session in 2003 (CmAT 2003: para 25). Again, this proposal met with strong procedural and substantive criticism from his fellow committee members. On the procedural side, he was criticized for sending out the draft to NGOs before consulting with CmAT (CmAT 2004b: paras 30, 32). While the NGOs had appreciated the sharing of the draft with them, they were not satisfied with the content. At this stage, there are no signs of building a collaborative relationship between CmAT and its environment. This failed attempt to draft a General Comment is counterfactual evidence of the crucial link between the committee members and outside experts in providing the resources that make law-making in General Comments possible and successful. It also suggests that General Comments are more needed where human rights treaties are imprecise than on already specified aspects such as the torture prohibition.

From internal disputes and civil society pushback to cooperation and adoption

CmAT’s attempts to draft a second General Comment were marked by internal disputes over substance and procedure and by pressure from civil society (CmAT 2004a: para 30). To overcome these problems, the committee finally decided in 2004 to set up working groups – also in an attempt to overcome the frictions within the committee after the previous ad hoc attempts. Between 2004 and 2006, the official records of CmAT show no further involvement of the committee in the issue. Meanwhile, CmAT member Felice Gaer had been working on an additional draft General Comment, which was tabled in 2006. Subsequently, Menéndez and Gaer became the co-rapporteurs for this General Comment. This second draft had been developed in close collaboration between Gaer, a political scientist by training, and outside experts on legal and gender issues (see also Davidson Reference Davidson2022: 217).Footnote 6 It was accompanied by an ongoing and lively exchange with other human rights NGOs, such as APT. During the same session, the committee made considerable progress and was able to send the draft out to NGOs, other UN bodies and states for final consultations (CmAT 2007a: para 67). While engagement with non-state actors at this consultation stage can be described as quiet, it should be noted that the Committee appears to be less responsive to input from states.Footnote 7 This illustrates the role of individual initiatives as well as external knowledge in the drafting of General Comments in the case of CmAT.

General Comment no. 2 was a direct response to the contestation by states parties in the fight against terrorism (Gaer Reference Gaer2008: 192; Rodley Reference Rodley2008: 358), which is also reflected in the drafting process (e.g. CmAT 2006a: para 8; CmAT 2006b: para 26). It is important for the development of the torture prohibition because it has defended the norm against powerful challenges in the fight against terrorism, thus contributing to its continuing robustness (Lesch and Zimmermann Reference Lesch, Zimmermann, Krieger and Liese2023). CmAT added an important clarification to the torture prohibition in human rights (Lesch Reference Lesch2023; see also Davidson Reference Davidson2022: 217–18). General Comment no. 2 has become an important reference point for the practice of CmAT, other treaty bodies and UN institutions,Footnote 8 and civil society actors; it is even cited by human rights courts.Footnote 9

The UN General Assembly acknowledged General Comment no. 2 in its biennial resolution on torture (UN General Assembly 2008: para. 26). Moreover, the (bi-)annual resolutions of the UN General Assembly on torture reflect the reaffirmation and interpretation of General Comment no. 2, especially with regard to its absoluteness and non-derogability. CmAT did not fundamentally alter the original treaty, but clarified its scope, which underlies its broad interpretation of the prohibition of torture and ill-treatment. As this was a response to US contestation, it was not surprising that the United States submitted a detailed response to General Comment no. 2 criticizing the committee for overstepping its mandate by adopting a document similar in tone and style to an ‘advisory opinion by the International Court of Justice’ (US State Department 2008). This reflects general US concerns about treaty change. It also underscores that General Comment no. 2 has placed additional normative pressure on its counter-terrorism activities.

VII. Conclusions

Human rights treaty bodies act as human rights law-makers – even in the absence of a formal mandate, intergovernmental decision-making and states’ consent. We have demonstrated this argument with two cases studies: General Comment no. 15 on the right to water adopted by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 2002 and General Comment no. 2 on the implementation and scope of the Convention Against Torture adopted by the Committee Against Torture in the wake of the ‘war on terror’ in 2008.

In this article, we have conceptualized General Comments as informal law-making instruments and as tools for human rights treaty bodies to actively protect and promote human rights. We have shown that, due to the particularities of the independent human rights expert system, treaty bodies have gone beyond their monitoring mandates and acted as law-makers. Building on our illustrative case studies, future research should take a comparative approach to analysing the drafting processes of General Comments across treaty bodies over time (Reiners Reference Reiners2022: 94–115). To explain the adoption and drafting process of these hitherto overlooked instruments, we have proposed a framework that can help to analyse law-making in international organizations by emphasizing the specific dynamics in expert bodies in contrast to intergovernmental forums; by capturing these dynamics in mostly informal processes in contrast to formal intergovernmental negotiations; and by demonstrating that (successful) law-making depends on individual efforts and close ties to actors outside the institution itself.

In our case studies, we illustrated the added value of this framework and its three major contributions to the debate on human rights law-making. First, we showed that quasi-judicial actors like the human rights treaty bodies make human rights law below the surface of formal law-making. CECSR and CmAT drafted and adopted two General Comments. These informal instruments substantially developed international human rights law. In doing so, the committees acted against stagnation in economic, cultural, and social rights and against contestation in civil and political rights. Second, transnational networks were key to both informal law-making processes as the committee members of CECSR and CmAT used their own position as independent experts and mobilized external expertise in the drafting process. In both cases, the framework revealed the need for external collaborators with expertise in the technical and legal aspects of the norms in question. These networks are also key for the dissemination of General Comments after their adoption. Third, our framework and case studies add further nuance to the ongoing debate about ‘who governs’ in world politics by demonstrating the power of expert authority. While being characterized by exclusive access through previously established relationships, law-making by expert committees proves effective because the outcome is driven by the needs of human rights, rather than by achieving diplomatic consensus as in intergovernmental negotiations. As such, expert committees can develop the law even in times of stagnation – maintaining a solid structure rather than ‘shackles’ (Pauwelyn, Wessel and Wouters Reference Pauwelyn, Wessel and Wouters2014) – and resist contestation even from powerful states. Depending on the issue at hand, however, General Comments will not suffice to develop human rights law where broad agreement is required for implementation.

While the framework proved useful for analysing the process once the decision to draft a General Comment by the treaty bodies has been made, the factors that explain when treaty bodies take the initiative are more difficult to assess. In both cases, the pressure on the norms and states parties was high but states were unable or unwilling to act. Where the cases differ is in the preceding nature of contestation: the issue of water was absent from the formal framework of the ICESR; the torture prohibition was at risk of being misinterpreted, potentially leading to a weakening of the norm. While the right to water was drafted in the light of future events, the timing of General Comment no. 2 was driven by recent events and long-standing interpretive disputes about the applicability of CAT. The General Comments also differ in terms of the nature of the treaty – a general human rights covenant versus a precise issue-specific treaty – and the size and composition of the treaty bodies. Future research will help us to understand more about these factors result in making challenges to human rights an issue to be addressed in a General Comment and the conditions under which they become effective.

This should include studying the normative implications for the international rule of law when treaty bodies act outside their mandates and interpret human rights beyond the original treaties. Within the human rights community, both General Comments are well disseminated and widely recognized, yet they have not gone unchallenged. The resistance to the General Comments on water and torture is evidence that states perceive these instruments as at least potentially authoritative, as they go to great lengths to criticize them. At the same time, more research is needed on the dynamics of contestation and (non-)recognition that follow the adoption of General Comments by the treaty bodies in order to better understand the opportunities and limits of their law-making efforts. The interactions between the treaty bodies and the UN General Assembly provide an excellent starting point. Moreover, the partial resistance to these and other informal law-making efforts raises important questions about the potential overreach of the authority of human rights treaty bodies – an issue that has been debated for some time with respect to international courts (see e.g. von Bogdandy and Venzke Reference von Bogdandy and Venzke2016; Waldron Reference Waldron2021). Treaty bodies can act as law-makers because their members are elected on the basis of their human rights expertise, which is well recognized in the human rights community. This allows them to act independently of national interests but also implies the potential threat of a backlash against treaty bodies in light of their (perhaps) growing authority.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive feedback. Previous versions of this article were presented in an online workshop on UN Human Rights Treaty Bodies and at the Global Networks Conference at Zeppelin University Friedrichshafen. We are especially grateful to Valentina Carraro, Audrey Comstock, Heidi Haddad, Nele Kortendiek, Andreas Ullmann, Andreas von Staden and Lisbeth Zimmermann for their comments. Open access publication enabled by a publisher agreement between Freie Universität Berlin and CUP.