A. Introduction—Contemporary Hungary (2010–2020) and the Socialist State (1949–1989)

The constitutional system and democracy of Hungary is frequently characterized as a “populist,”Footnote 1 “illiberal,”Footnote 2 “hybrid,”Footnote 3 or “semi-authoritarian”Footnote 4 regime.Footnote 5 The Fundamental Law of Hungary entered into force on January 1, 2012 and was adopted by the two-thirds constitution-making political majority of the Fidesz-Christian Democrat party coalition. Article U) of the Fundamental Law states that:

(1) The state structure based on the rule of law, established by the will of the nation through the first free elections held in 1990, and the previous communist dictatorshipFootnote 6 are incompatible. The Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party and its legal predecessors and the other political organizations established to serve them in the spirit of communist ideology were criminal organizations, and their leaders shall have responsibility without a statute of limitations for a) maintaining and directing an oppressive regime, violating the law and betraying the nation . . . .Footnote 7

I will argue here that although the new Hungarian constitution rejects the Socialist period, certain attitudes in legal policy live on,Footnote 8 and similarities appear, if not primarily in the legal texts, at least in the conceptual framework. In this Article, I will focus on the influence of significant political—in practice supra-legal—concepts on the interpretation of law introduced by one political power unilaterally. I argue that in regimes with centralized state power, over time these concepts begin to influence not only the specific legal design, but the judicial interpretive practice as well. I will explain how the transformative nature and value of these concepts are, for many of us, still familiar from socialism.

The concept of “socialist legality” gave normative but flexible content to a particular understanding of the law and laid out the optimal space for the independence in legal interpretation for the judiciary by formulating an uncertain conceptual framework. Being a familiar concept in Hungary, it is easier to understand “constitutional identity” as introduced into Hungarian law in 2016 and assess what it contributes to the legal system through the slow transformation of the law’s interpretation, application, and judge’s attitudes themselves.

I will examine this hypothesis after the introduction of the concept of socialist legality by Prime Minister Imre Nagy following Stalin’s death, with particular regard to the judiciary and judicial decision-making environment created by the Act of 1954 on the court system, which was in force until 1972. In 1972, a new era started with the constitutional revision and the new act on the judiciary. To match socialist legality with constitutional identity, I will continue the story from 2011 when the two-thirds Fidesz-Christian Democrat parliamentary majority introduced judicial reform and adopted the new constitution, the Fundamental Law and the concept of constitutional identity appeared in 2016.

This Article proceeds as follows. Section A explains socialist legality and the transformation of the rule of law after 1954 by using the example of the regulation of the judiciary. In Section B, I will describe the recent changes in these issues in Hungary since 2011. Section C, the comparative conclusion, explains the similarities between the two periods. My inquiry addresses the similarly specific supra and quasi legal character of the two concepts and their possible affect on independence-related judicial attitudes in the interpretation and application of the law.

B. Socialism and Forms of IndependenceFootnote 9

I. The Concept of Socialist Legality

The concept of socialist legality first appeared in Hungary in the 1950s, during Imre Nagy’s premiership. Nagy was appointed prime minister of Hungary in 1953, in a period of uncertainty after Stalin’s death. He was a devout communist who was not ready to give up absolute power, but at the same time, he opposed the Stalinist politics of his predecessor, Mátyás Rákosi, and he did not want his people to live in constant fear and terror.

To make people understand that times were changing, Nagy promised the country in 1953 that he was going to restore socialist legality.Footnote 10 In Nagy’s interpretation, socialist legality meant that power is exercised in harmony with socialist laws. This was a specific understanding of the rule of law. Consequently, he did not object to the Constitution and the laws introduced by the communist regime, he simply thought that Rákosi had not abided by them. Furthermore, he urged his government to start codification in areas classically viewed as having constitutional relevance.Footnote 11 It is no coincidence that the regulations analyzed later in this Article—the act on the organization of the courts and the decree on public prosecution—both entered into force in this period. This was not unique as a tendency in the Socialist part of Europe.Footnote 12

After his involvement in the Revolution of 1956, Imre Nagy was killed by his former comrades. However, the concept of socialist legality did not die with him. Instead, it remained in use both by those who had participated actively in Nagy’s liquidation and the revolutionaries.Footnote 13

In the 1960s, the term gained a new meaning thanks to the chief legal theorist of the Kádár regime, Imre Szabó. He examined the Western idea of the rule of law and condemned those who thought that socialism could be built in such a system.Footnote 14 He emphasized that the rule of law seemingly served everyone’s interests, but in fact, it only suited the enemies of the working class. This is why a socialist state had to create a legal order which worked by the same logic, but which protected the needs of the proletariat.Footnote 15 Szabó called this system socialist legality and argued that it could not be interpreted in a purely formal way. In his eyes, socialist legality was superior to the rule of law simply because its purpose was better. Nonetheless, as this Article will illustrate through the example of the independence of the judges, the criteria of socialist legality were frequently infringed upon right up until the end of the Kádár era.

The first judicial act based on socialist legality that entered into force in 1954 rejected the Rákosi dictatorship, the previous uncertainty in political actions not governed by law, and the arbitrariness of the judiciary.Footnote 16 This Act emphasizedFootnote 17 that Article 41 (2) of Act XX of 1949 on the Constitution of the People’s Republic’s declares: “In the Hungarian People’s Republic the judges are independent and subject only to the law.” In this period, the administration of the judiciary was sufficiently well-established to serve the independence of the judiciary and the judges, although as an element in the Constitution, based on the unity of power.

According to Imre Szabó, the action of the State must embrace the will of the ruling class, as represented by the ruling class’s authentic representative, the Party.Footnote 18 The Party formulates the intention, but its manifestation becomes evident in state action. Socialist legality is about this interaction involving the constructed will of the people, the Party, and the State and its legal action. The general will, the source of the state action, is abstract; it is impossible to ask concrete questions about it because to do so would give a reason to contest this will as the source of the party’s position and the power of the state. While the reason for the codification of the rules is purely societal and economic in a bourgeois state, in a socialist state it is necessary in order to satisfy the ruling class’s need to provide legal certainty and effective central administration of the state.Footnote 19 Szabó also talks about the importance of an integrated legal policy. This integrated legal policy is determined by the Party—as are general policies—in order to provide legal security. This concept requires that the law be interpreted and applied according to the general and judicial policies of the Party. The concept of socialist legality as a normative but quasi and supra legal concept makes the law instrumentalFootnote 20 because this particular understanding of the rule of law means that the law’s aim is not to establish the rule of law, but the rule of the Party.Footnote 21

II. The Socialist Judiciary and its Administration

The judiciary has traditionally been regarded as an independent branch of state power in Hungary since courts were first separated from the executive in the second half of the 19th century.Footnote 22 The history of the administration of justice between 1949 and 1990 was not straightforward and uninterrupted but, according to Szente’s study in this Special Issue, it can nonetheless be divided into several stages. Between 1948 and 1950, the legal and human resources of the proletarian dictatorship were established. This period was followed by a period of totalitarian dictatorship until 1953, under which the courts were instruments of political repression. The “new phase” between June 1953 and April 1955 sought to limit the dictatorship’s infringements within the framework of socialist legality, while after the suppression of the 1956 revolution until 1962, the courts again became the instruments of repressive action against the revolutionaries. After the consolidation of the Kádár regime, especially after the constitutional amendment of 1972, the judiciary was consolidated and judicial independence, within the limits of the socialist authoritarianism, was strengthened. In the late 1980s, the courts became more and more independent of the control of the Communist Party.Footnote 23

The literature explains that before the Act II of 1954 on the court system of the Hungarian People’s Republic, the applicable law on the courts was mainly the law that had been in force in Hungary before the Second World War.Footnote 24 However, from the point of view of our research, it is not worth analyzing this in detail because in the Rákosi period of communist dictatorship, the courts did not operate lawfully, but rather arbitrarily. People’s courts and revolutionary justice were established with a single-instance jurisdiction, and these courts worked entirely according to the rules of a dictatorship.Footnote 25 The period when socialist legality prevailed was a break with the previous dictatorship.

It is interesting to note that the 1956 Revolution and the related judicial proceedings were only partial exemptions from the general rule of consolidated socialist legality because the courts continued their operation almost without interruption in civil and economic matters.Footnote 26 In sum, the period before 1954 and the jurisprudence related to the 1956 Revolution must be distinguished from the socialist legality achievements in jurisprudence as codified primarily in Act XX of 1949 on the Constitution and Act II of 1954 on the court system.Footnote 27 Nevertheless, 1972 was another turning point, when Act IV on the courts was passed according to the general revision of the Constitution. This act brought essential changes in the independence of the courts in a positive direction.Footnote 28 In this period, the judiciary’s independence was soon interpreted at that time very similarly to the “Western bourgeois concept.”Footnote 29

III. Socialist Legality and Judicial Independence in Books

Judicial administration as a broad concept is everything that happens outside the courtroom but is connected to judicial activity. According to Act XX of 1949 on the Constitution and Act II of 1954 on the court system, the Minister of Justice, the courts themselves, the representative bodies of the people at different levels—local and territorial councils and the Parliament—and the Public Prosecutor took part in the administration of the judiciary. The proper administration of the judiciary according to the very contemporary language of the act guarantees an independent and competent judicial service.

In this section, dealing with the formal administration of the judiciary, we must, however, say a few words about the role of the Public Prosecutor. Although this is not strictly related to the administration, it is vital for a general assessment of the legal environment of the daily operation of the judiciary. The Public Prosecutor’s task in the Hungarian People’s Republic was the control of the legality of criminal justice and its implementation. The Public Prosecutor was responsible for controlling the legality of the ministries and local authorities concerning regulations, ordinances, and other dispositions. The Prosecutor had the right to initiate any civil procedures apart from the criminal procedures and the right to intervene in any part of the process on behalf of any of the parties.Footnote 30

According to the act, the heads of the first instance courts, the heads of the second instance courts, and the Supreme Court—as judicial bodies—had a say in court administration matters.Footnote 31 Furthermore, according to the act on the court system, the Supreme Court was responsible for the administration, control over the operation, and jurisprudence of all courts. The head of the Supreme Court directed the Supreme Court and dealt with the distribution and treatment of the petitions in due time. The head of the Supreme Court decided on the appointment of judges in the different divisions of criminal law and civil law. The head of the Supreme Court had the right to take any of the court cases from the lower courts and proceed with the trial before the Supreme Court. According to Act II of 1954, the heads of the regional and local courts had similar tools. In these times, there was no self-government of the court system. The appointment, the removal, and the discipline of judges was much more straightforward and hierarchical, with far fewer guarantees than nowadays.

Article 39 of the 1949 Constitution stated that in the Hungarian People’s Republic all positions in the courts are filled by election. Judges can be recalled from their positions. The election of judges is not specified in the Constitution, except for the election of the Supreme Court judges by the Parliament, but it is clear that elected judges are responsible to the people and can be recalled under certain circumstances.

Judges and lay judges—it was a joint adjudication system with social, lay participationFootnote 32—could be any Hungarian citizen with a clean record who had the right to vote and was over twenty-three years old.Footnote 33 Judges and lay judges were mentioned together in the text of the law; according to the legal analysis of this period, the lay element did not play a significant role, which means that the judicial decisions were taken under the guidance of the professionals. Becoming a judge in this period was not a very popular vocational choice,Footnote 34 and the prestige and remuneration of the individual judge was not very high in the Budapest law schools, such that only a few students were keen on becoming a judge.Footnote 35 In the countryside, the situation was slightly different because being a judge was a prestigious job. Therefore, it mattered a good deal for the judge which city, bigger or smaller, accepted his or her services. There was competition to be appointed to a bigger, more cosmopolitan town, rather than a remote location, where the quality of life was completely different. According to the rules, nobody could be removed from their place of service without their consent. Professional judges could not conduct any other non-academic or artistic professionsFootnote 36 in order to preserve their independence, and incompatibility rules were formulated in a markedly standard way. The general regulations on appointments in Act II of 1954 on the court system went as follows:Footnote 37 The heads of the local first instance courts and the local councils elected professional and lay judges for three years upon the nomination of the Minister of Justice. The county councils elected the head of the county courts and their judges and lay judges for three years upon the proposal of the Minister of Justice. According to Article 39 of the Constitution, the head of the Supreme Court, deputies, judges, and lay judges were elected by the Parliament for five years.

Although the relevant paragraph of this law does not mention the nomination procedure, this nomination was also made by the Minister of Justice. According to the 25/1963 NET (Presidential Council of the People’s Republic / the body functioning as head of State) resolution point 2, the Council of Ministers was responsible for the appointment of the heads of the local and regional courts and all other judges were appointed by the Minister of Justice.

As to the general rules on removal and the disciplinary measures in Act II of 1954, the following rules applied. Professional and lay judges could be recalled before the termination of their office if they had committed a crime, carried out their tasks in a negligent manner, or if their conduct otherwise violated the authority of the people’s justice system.Footnote 38 The electoral body could recall judges and lay judges upon the initiative of the Minister of Justice. The prosecution and removal of a judge was only possible upon the initiative of the Public Prosecutor with the consent of the President’s Council of the Hungarian People’s Republic. The Minister of Justice was responsible for the administration of the judiciary. In this period, there were no detailed rules on the qualification or measurement of judicial work. The number of appeals was, however, a good indicator in this period, as it appears in literature,Footnote 39 but no other specific, generally indicated control mechanism existed.

The Act on the court systemFootnote 40 included the requirement that judges must be exempt from criticism. They must complete their tasks with sincerity and due attention. If a judge was negligent or irresponsible, he or she would be unworthy of the authority of the Hungarian People’s Republic or its justice system, and this would constitute an offense against the discipline. In cases involving heads of courts and professional judges, the disciplinary procedures were conducted by the disciplinary committees operating at the county courts, the Budapest Court included, and the Supreme Court. There was the right to appeal against such a ruling, and the Public Prosecutor and the Minister of Justice could also raise a request for appeal. Even after the decision had come into force, it was still possible for these bodies to initiate a review of the legality of the decision. The consequence of the disciplinary procedure could be a charge, censure, severe reprimand, and finally, the initiation of the judge’s recall. The Committee of Ministers formulated the detailed rules of the disciplinary procedure according to the law.

I will argue in the following section that within the above legal framework the influence of the concept of socialist legality led to a particular understanding of the rule of law and judicial independence. Also, I will argue that instead of legality in the strict sense, room was allowed for the ruling political ideology in the application of rules.

IV. The Practice of Judicial Administration

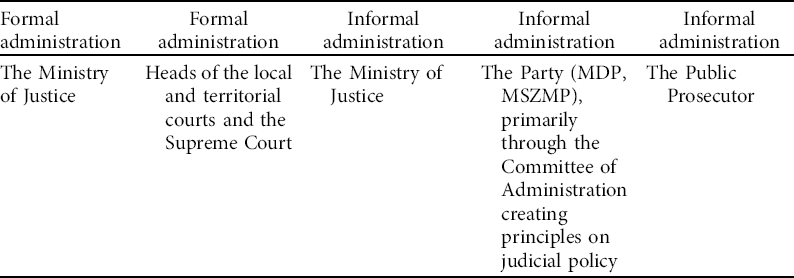

In real life, I suggest that the system of judicial administration consisted of different types of administration in both formal, statutory and regulatory, and informal senses. The informal impacts were to correct and guide judicial work to ensure a better enforcement of socialist legality. Any correction in the application of positive law was entrusted to the political power and other state institutions that were openly more connected to the party.Footnote 41 Judicial policy in the name of socialist legality was created by and large by the State, which was ruled by the Party, but civil matters, for instance, were not coordinated directly, and therefore the judges were not under direct pressure. The situation was somewhat different in criminal matters because there could be sensitive cases where the previous central opinion on the case was submitted to the judge.Footnote 42 Economic cases were not judged by the ordinary courts in this period, and most civil law matters, such as marriage disputes, were adjudicated without the need for political influence. It was only in some criminal cases that political influence appeared. Everyone who became a criminal judge in Hungary was clearly aware that this influence had to be accepted as the state power was unique and its goals were formulated primarily by the political branches of state power. The influence and the pressure, for example, that the interpretation of one or the other legal rule should be transformed according to the broader state goals of socialist legality articulated by the centralized party state, could be made explicit by the judicial administration. I have collected in the table below the formal and the informal sources of authority used to create an atmosphere restricting a judicial decision.

1. Public Prosecutor

According to the literature,Footnote 43 the Public Prosecutor, as the voice of the supreme decision-makers, had a significant influence on the judiciary’s operation not only in criminal cases but also in some civil law disputes where he had the right to almost unlimited intervention. It was also possible for the Public Prosecutor to take the case or start a disciplinary procedure against a judge. Therefore, while the administration’s technical aspects were governed mostly by the Ministry of Justice, the Public Prosecutor and his office safeguarded legality in substantive and procedural matters. As I have noted above, the Public Prosecutor’s Office—the structured operation of the Public Prosecutor—was reorganized and re-established in 1954, but it became important as the supervisor of the courts’ legality. Interestingly, the Prosecutor’s status was the same as that of the judge, and their judicial disciplinary committees were identical.Footnote 44

The head of the public prosecution was also elected by the Parliament and could participate in Government sessions, but was not instructed directly by the Minister of Justice or by the Party.Footnote 45 He was a member of the so-called Coordination Committee of the Administration of Justice, a very important political institution that consisted of the Head of the Supreme Court, the Public Prosecutor, the Minister of Justice, and the head of the Department of Administration of the Central Committee, and the Minister of Internal Affairs. This committee was secret and informal and was the supreme body of the judicial administration and coordinated judicial policy.Footnote 46

2. Heads of the Courts

In regard to the pressure put on the judges, the “Hausrecht” always played a role. The rooms, equipment, and the physical location of the service were always important tools used to influence the judges, especially when the system was not wealthy. As the heads of the courts had the right to administer the court, it was necessary to have political consent from the head of the courts on the local level as well, although at very small courts it was a challenge to find professional judges that would be acceptable to the Nomenklatura.Footnote 47

Before 1972 it was possible to become a professional judge without a legal qualification, but in practice, between 1954 and 1972, most professional judges had a law degree. It was only the 1972 reform which introduced this as a requirement.

One major tool of influence exercised by the heads of the courts was the distribution of cases. As there was no rule for the distribution, the most important or sensitive cases could go to those judges who had the right place in the Nomenklatura, or were otherwise reliable. Later, in the 1980s, there was a protocol for the distribution of cases, but this could also be overruled in important and sensitive cases.Footnote 48

3. The Ministry of Justice

According to the democratic principle, even if the judges were elected by one of the State’s representative bodies, they were appointed by the Minister of Justice to their place of service, and the Minister also decided on which division, civil or criminal, they would operate in, even if the law stated otherwise. It was also possible for someone to be appointed to one particular court, for instance, the transport court, when it existed.Footnote 49

4. The Party and the Coordinating Committee

Of the criminal judges, the majority became Communist Party members, while for the civil law judges Party membership was probably not so important. In the most important cases, discipline and pressure could also come from the Party in the form of party discipline. Although the collected data does not show a significant number of these procedures, as judges were members of the Party, it was also a pressure that might have affected their behavior and attitudes in the interpretation of the law. The Nomenklatura oversaw the human resources politics of the Party, and it was evident that everyone had a ranking in this system.Footnote 50

According to the documents discovered by Béla Révész in 2010, the Coordinating Committee was the center of the informal administration. They decided mostly in questions of judicial policy and individual cases when it was in the party’s interest. The Committee probably worked from 1957 to 1988, but the related documents were discovered only for the period from 1965 onwards. This secret committee was mentioned several times by the leaders of the Party and the State as a reference point in the judicial administration.Footnote 51

C. The Era of Illiberal Democracy: 2010–2020

Hungary is categorized as a Member State of the European Union (EU) ruled by a populist Government.Footnote 52 The Hungarian government is qualified as populist because, according to the scholarship of political science, many elements of the definition of populism fit with the Hungarian political system. Furthermore, the Government has a two-thirds constitution-making majority in the Parliament; therefore, Hungary’s constitutionalism since 2010 has been formed and transformed by the ruling political majority alone. As political goals can easily be transformed into constitutional changes and the constitutional environment adapts to the political agenda immediately, the scholarly criteria of so-called populist, or as it is otherwise known illiberal constitutionalism, can be observed in Hungary.Footnote 53

I. The 1989 Democratic Transition and the Contemporary Notion of Judicial Independence

Judging cases is a monopoly of the ordinary judiciary in contemporary Hungary.Footnote 54 During the democratic transition of 1989, building the organizational system of the judiciary and guaranteeing judicial independence were essential issues as the operation of the socialist court system was reorganized. Judicial independence became the crucial principle of court activity. The rule of law was promoted by the 1989 complete revision of Act XX of 1949 on the Constitution. Judicial independence was interpreted as an institutional and a personal goal within this new rule of law framework.

According to the “1989 Democratic Constitution of the Hungarian Republic,” the judiciary is a separate branch of power, independent of the other two traditional branches, the legislative and the executive. The courts act independently; no other body can supervise their jurisprudence. Judges must be independent and only subordinated to laws, and they cannot be instructed concerning their judicial activities. Besides, judges may only be removed from office for certain reasons and in a procedure specified by law. Judges may not be members of political parties or engage in political activities. In addition, the appointment procedure is also a constitutional guarantee of judicial independence, as only the President of the State may appoint the judges.

After the democratic transition, the Hungarian Constitutional Court declared that the judiciary, contrary to the other two “political” powers, is stable and neutral.Footnote 55 It is also an absolute requirement that judicial adjudication is independent of any external influence, and is under an absolute constitutional protection.Footnote 56 However, judicial independence does not mean unlimited judicial power, as the courts are also subject to the law.Footnote 57 The courts’ exclusive power to decide on litigation includes their duty to provide legal protection to the parties in cases that fall to their jurisdiction. Creation of the National Council of Justice can be mentioned here as an important milestone in court administration.

II. The 2011 Judicial Reform and Failed Attempts at Legislative Influence

In 2010, when the Fidesz-KDNP party coalition won a two-thirds majority in Parliament, the Hungarian judiciary reform started again. Before 2012, the National Council of Justice, as a self-governing body, was charged with the administration of the courts. Claiming that the old institution was slow and nepotistic, the new regulation, founded in the Fundamental Law, introduced new institutions.

Between 2010 and 2012, the government gradually altered the whole judicial system. The most important sources of the legal status of the courts include the chapter on Courts, Articles 25–28 of the Fundamental Law of Hungary—the constitution—of 2011, the Act CLXI of 2011 on the Organization and Administration of Courts, and the Act CLXII of 2011 on the Legal Status and Remuneration of Judges. Courts administer justice, decide on criminal matters, civil and administrative disputes, and other matters specified by law. These reforms focused on creating a more centralized and accountable administration of justice by establishing a more efficient and faster judicial activity.Footnote 58 Central to the judicial reform was the thorough modification of the processes of selection, discipline, and unsuitability for office proceedings. Even though the reforms of 2010–2012 changed the situation of judges in many respects, as was the case with the selection and removal of judges, the protection of independence and professionalism seemed to be a primary goal of the changes.Footnote 59

The result of the new codification, however, was contestable in many regards. Three leading NGOs (non-governmental organizations) summarized that:

[W]hile the deficiency of the former model of administration was that judicial independence was placed before any other interest, the new administrative model, and the one-person decision-making mechanism, directly threatens the formerly protected judicial independence.Footnote 60

The Venice Commission also argued that the President of the National Office of the Judiciary has uncontrolled competencies pursuant to the law.Footnote 61 Following the national and international criticism of many provisions of the acts of Parliament on courts, judges, and the prosecution office in Hungary, implemented in 2011 and entered into force at the beginning of 2012, specific provisions of the Act were amended and the appointment of judges was no longer solely in the hands of the President of the National Office of the Judiciary.

The President of the National Office of the Judiciary further performs tasks of the central administration of courts. To ensure operational efficiency, the President was vested with extensive duties and responsibilities for the central administration.Footnote 62 Among others, under Article 76 of the Act on the administration of courts, in his/her role regarding matters of human resources, the President publishes vacancies for judges, puts forward proposals to the President of the Republic concerning the appointment and removal of judges, and nominates judges. The President may adopt a decision on the transfer of the judge. The judge’s posting to another place of service, decides, furthermore, whether or not the court’s territorial jurisdiction has diminished to the degree that makes the judge’s further employment there impossible, and many other important matters, almost all of which are related to significant administrative issues, are decided too. The system became centralized. The heads of the upper appellate courts, appointed by the President of the National Office have further tools in organizational matters but these are much less significant than they were.

The National Judicial Council also plays a vital role in the procedure for the appointment of judges, although a much less important role than the President of the National Office of the Judiciary. The Council comprises fifteen members elected by a council of the representatives of the Hungarian courts. This body should advise and approve the decisions of the President of the National Judicial Office, but its consent is not necessary for the decision.

Lastly, due to their role in the selection procedure, the so-called judicial boards must be mentioned. These boards are responsible for the preparation of the decision. Each regional court must elect a self-governing body. These boards are elected by the regional council of judges, which have five to fifteen members.Footnote 63 One of their primary duties is to participate in the appointment process by interviewing applicants and make rankings, but compared to the former legislation, they lost most of their competence apart from this task.

Despite the detailed regulation of the court system’s administration and the selection of judges, several controversial issues have emerged in recent years in Hungary.Footnote 64 Apart from the concerns related to the extraordinary competence of the President of the National Office of the Judiciary in the administration, which necessarily influences indirectly the independence of the adjudication activity, constitutional concerns were raised in a case related to the socialist past as well.

The new Government, with the two-thirds majority constitution-making power, wanted to break with the past, which in practical terms meant dismissing the judges who were socialized in the socialist period before the democratic transition of 1989. The new parliamentary majority soon decided on the forced retirement of judges at the age of sixty-two.Footnote 65 Consequently, this meant that suddenly more than 200 judges lost their positions, most of whom were in leading roles. On July 16, 2012, the Hungarian Constitutional CourtFootnote 66 declared that implementing provisions relating to judges’ retirement age was unconstitutional. However, that ruling did not reinstate the retired judges to their former positions as most of these positions had already been taken by the decision date. The Constitutional Court stated that Section 230 of Act CLXII of 2011 on the legal status and remuneration of judges was unconstitutional. Therefore, the Constitutional Court struck down this section retroactively, as of January 1, 2012. The Constitutional Court emphasized the necessity and importance of the independence of judges in this decision. Under the Fundamental Law of Hungary, the judge’s independence is the most important guarantee of the autonomous application of law. One element of the independence of judges is personal independence. This means that the judge may not be ordered to step down and may not be removed against her/his will. In other words, the appointment of a judge is for life. The independence of the judge requires several guarantees from other branches of the government.

The Constitutional Court determined in this case that the Fundamental Law of Hungary did not include the age of retirement. Act CLXII of 2011, on the legal status and the remuneration of judges, did not regulate retirement age either. The phrase in the legal text indicating the “average age of retirement”Footnote 67 did not entail a precise legal definition due to the continuous transformation of the retirement system. However, for judges, the upper age limit of retirement had been seventy years old for more than a century,Footnote 68 and it was seventy when the Fundamental Law of Hungary came into force in 2012. Judges older than sixty were responsible for deciding many cases. To take these cases from them—as the Constitutional Court argued—contradicted the general principle that judges cannot be disengaged from cases unless there was an exceptional circumstance. The argument from constitutional tradition was decisive in this case. This entailed a reference to the historical constitution in one of the concurring opinions and an interpretation of the doctrine of “legitimate expectation” that otherwise did not exist in this form in the Hungarian jurisprudence.

Furthermore, the European Commission of Democracy through Law stated that although the legislator claimed that these provisions are “just transitional with a view to the reduction of the upper age limit to sixty years and shall allow for a smooth and gradual retirement,” the provisions’ transitional character is not stipulated in the Law, and it is difficult to find any justification for why judges especially need a “smooth and gradual retirement” by exempting them from office.”Footnote 69 After the Hungarian Constitutional Court’s decision, the Opinion of the Venice Commission of the Council of Europe of October 15, 2012 called upon the Hungarian legislator to adopt provisions reinstating the dismissed judges to their previous positions without requiring them to go through a reappointment procedure.Footnote 70

The European Court of Justice found in the same case a violation of EU law. At the European Commission’s request, the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled that the radical lowering of the retirement age for judges, prosecutors, and notaries in Hungary violated EU equal treatment rules.Footnote 71 According to the Court’s judgment, the forced early retirement of hundreds of judges in 2012 constitutes unjustified age discrimination.Footnote 72

The EU Court of Justice did not find any objective justification for the drastic lowering of the age limit of judges. Besides, in view of the brief transitional period for such an extensive reform and the contradiction of first drastically lowering the age limit before raising it again in 2014, the European Court of Justice found the measure disproportionate, and therefore not in compliance with Directive 2000/78/EC.Footnote 73

The above case involving the forced retirement of judges is a good example to illustrate the relationship between the present and the past. From the institutional perspective, the State wished to have a purged judiciary, although the democratic transition was based on legal continuity and the lack of lustration laws. This decision on continuity meant that the independent judiciary personnel remained in position due to the recognition of their former independence. Yet, the method of introducing a change to the composition of the personnel of an independent constitutional institution, the judiciary, failed in legal terms, although in practice most of the judges could not or did not want to claim their actual position back after the long judicial procedure.

The attempts at influence were harmful in the long run, not only because of their immediate and actual results, but also because of the uncertainty they caused. Judges currently in office must bear in mind that even if their status is secured, the constitution and the cardinal laws may be easily amended by the votes of a two-thirds majority. Change comes from one day to the next and can unforeseeably threaten the status of individual judges and the organization as well.Footnote 74

As many of the legislative and constitutional attempts to put institutional pressure on the judiciary and its daily operation have failed in recent years, partly due to international and EU concerns, the ruling majority have introduced other ideas to emphasize the necessity of change in the new political regime. I consider the role of the concept of the constitutional identity in the last section.

III. An Influential Concept: Constitutional Identity and its Role in Ordinary Jurisprudence

In Decision 22/2016 (XII. 5.),Footnote 75 the interpretation of the Fundamental Law had been requested from the Constitutional Court by the ombudsman. As explained in the motion, the concrete constitutional issue was related to European Union Council Decision (EU) 2015/1601 of September 22, 2015 on migration, but the ombudsman initiated the authoritative interpretation of Article E) of the Fundamental Law related to the accession to and cooperation with the EU. In this decision, the Constitutional Court developed the notion of constitutional identity to identify the particular approach of the Hungarian State to constitutional rights and values and to the rule of law. The concept of constitutional identity had not thus far been present in any domestic legal text. Significantly, the case was decided at a moment when the Government had already failed to get through a constitutional amendment with similar content, because in those months it did not have the two-thirds majority in Parliament, and an attempt to incorporate such a rule by a referendum had also failed.Footnote 76

The Constitutional Court stated that the EU provides adequate protection for fundamental rights. The Constitutional Court, however, cannot set aside the protection of domestic fundamental rights, and it must grant that the joint exercise of competences with the EU would not result in a violation of human dignity as protected by the Hungarian Fundamental Law or the essential content of other fundamental rights. The Court set two main limitations in the context of the question regarding the legal acts of the Union that extend beyond the jointly exercised competencies. First, the joint exercise of competence cannot violate Hungary’s sovereignty. Second, it cannot lead to the violation of its constitutional identity. The Constitutional Court emphasized that the protection of constitutional identity should take the form of a constitutional dialogue based on the principles of equality and collegiality, implemented with mutual respect.

The Constitutional Court of Hungary interpreted the concept of constitutional identity as Hungary’s self-identity, and according to the decision, it will unfold the content of this concept from case to case, based on the whole Fundamental Law and specific provisions thereof, following the National Avowal and the achievements of our historical constitution —as required by Article R) (3) of the Fundamental Law.

This decision was overwhelmingly criticized in constitutional scholarship because of its arbitrariness.Footnote 77 I argue here shortly, without discussing the decision on the merits, that this new substantive concept of constitutional identity—even if it exists in many other jurisdictionsFootnote 78—was developed in Hungary in line with populist political goalsFootnote 79 because it serves as a basis for protective national constitutionalism against EU or international legislation, which is considered to be elitist, internationalist, pluralist, liberal, and pro-migration, according to existing political communications.Footnote 80 Proof of this argument is that as soon as the Government majority in Parliament regained its two-thirds constitution-amending majority, Parliament added the notion of constitutional identity to the Fundamental Law’s textFootnote 81 in Article R), with the Seventh Amendment to the Fundamental Law in 2018. According to Article R) 4 (4): “The protection of the constitutional identity and Christian culture of Hungary shall be an obligation of every organ of the State.”

With this step, the constitutional identity concept gained relevance not only in terms of international cooperation but also of the domestic understanding of the law. Article R) contains provisions on the required methods of interpretation of the Fundamental Law. This approach opens an uncertain, case-by-case interpretation of a central substantive concept related to the interpretation of all the other Fundamental Law provisions.

Furthermore, with the Seventh Amendment to the Fundamental Law, the notion of constitutional identity gained further relevance in the daily interpretation of the ordinary law. In the preamble of the Fundamental Law, the National Avowal, we can read: “We hold that the protection of our identity rooted in our historic constitution is a fundamental obligation of the State.” According to Article 28 of the Fundamental Law:

In the course of applying the law, ordinary courts shall interpret the text of laws primarily per their purpose and with the Fundamental Law. In the course of ascertaining the purpose of a law, consideration shall be given primarily to the preamble of that law and the justification of the proposal for the law or amendment. When interpreting the Fundamental Law or laws, it shall be presumed that they serve moral and economic purposes which are [in accordance with] common sense and the public good.

The Constitutional Court can review the judicial decision in the German-type constitutional complaint of the Article 24 (2) d), procedures provided by the Fundamental Law. Therefore, the application of Article 28, the assessment of the Fundamental Law, and the decisions of the Constitutional Court became an obligation for the courts.

This means that during this period in Hungary, the ruling political power created a legal framework where the influence on the daily work of the judiciary is influenced through new concepts implemented by the Fundamental Law and other laws that can be unilaterally changed by the same two-thirds majority sitting in Parliament since 2010, and controlled by the Constitutional Court whose fifteen members were elected by this parliamentary majority.Footnote 82 Just like the content of constitutional identity, the requirement it poses is formed openly on a case by case basis, and it is the fifteen member Constitutional Court that can decide, even in a five member panel, on decisions in constitutional complaint cases about the obligatory interpretation of one or the other legal provision.Footnote 83

Constitutional identity is therefore a new concept that suggests a divergence from the Western type, common EU, and international rule of law standards. Constitutional identity emphasizes national particularities and specificities, while creating pressure on the ordinary judiciary when taking seriously the requirement to conform with a constitutional concept that is uncertain and determined unilaterally by the Government majority and by the members of the Constitutional Court elected by this majority. If the judiciary does not conform to this, the decision can be annulled.

D. Comparative Conclusion

In this Article, I have compared two periods of the legal system, the Socialist Hungary and the illiberal constitutional regime after 2012, that seem to be very different. In these two periods, rule of law concerns were raised, and particular understandings of the law and justice were formulated. The judiciary is the primary state institution or branch of power responsible for enforcing the law in disputes. Therefore, I have focused on the legal environment of the judiciary in both periods in order to understand the constraints on the interpretation and the application of the law in a state in which one political party rules with a constitution-making majority. To understand the particular approach to the rules of the law and the role of the judiciary, I examined the concepts that underlie this special approach to the rules of law, and I examined how the new concepts were realized in the legal environment. The legislation on the court system, the status of the judges, other formalized and non-formalized ways of negotiations, and review allowed us to understand the nature, or perhaps the limits, of the independence of the judiciary in the two periods.

I have argued that although the new Hungarian Fundamental Law in Article U) rejects any relationship with the Socialist past, there are fundamental attitudes towards law and justice that appear to be similar in the two eras. I have argued that general concepts such as socialist legality and constitutional identity influence the entire legal order, and that constitutional interpretation and legislative and judicial work equally. Furthermore, this political approach leads to similar uncertainties in interpretation on a daily basis, and thus room for sliding influence. This legal atmosphere results in an unceasing judicial search for the proper interpretation of the law, which is not defined a priori and concretely by law, and cannot be revealed by any common methods of legal interpretation.

The similarity between the two periods examined lies much more in the uncertainty of the due application of the law by the introduction of the new concepts than in the institutional design itself. What is also similar, however, is that formal influence on daily judicial work is rare; even the institutional impacts are designed to be somewhat hidden and not straightforward. I have explained that compared to 1953, the end of Stalinism brought significant attempts to guarantee some independence to the judiciary. However, it was different from the “bourgeois rule of law” standards; the limits of independence were framed abstractly, partly by the concept of socialist legality.

Moreover, we have seen that since 2011, Hungary has claimed to create guarantees of independence. Although there have been several attempts at direct intrusion in the operation of administrative matters, several of these attempts have failed because of constitutional, interpretational, and EU law constraints.

Let us suppose that the concept of legality is determined in law by externally introduced factors such as compulsory quasi-judicial concepts that alter legality to conform with the new standards. In this case, the atmosphere of uncertainty becomes a stress in a judge’s daily work, and a transformative atmosphere rules when applying the law.

In Marxism, this serves as a basis for socialist legalism because the final goal is to criticize liberal political philosophy.Footnote 84 The judiciary’s independence is a central element of the bourgeois or western type rule of law concept as the judiciary is responsible for imposing restraint on power and limiting the Government. If the Government does not intend to be limited, as is the case in the two periods of Hungarian history I have examined, the judiciary needs to be captured. It can be captured by administrative rules of discipline, appointment, removal, instruction, and new quasi and supra legal concepts that are compulsory for interpreting the law. I have explained that socialist legality and constitutional identity, as employed by the new constitutional regime in Hungary, are similar in nature and similar in their functions in their particular legal environments. Both are instrumental in creating a particular understating of the rule of law to enforce socialism and illiberalism. Socialist legality as regards legality, and illiberal constitutionalism as regards constitutionalism, are similar political ideas, and both instrumentalize law and deprive it of the autonomous nature that makes it capable of limiting the governing power. Path dependency might indicate that the general acceptance and obedience to this new constitutional idea in 2021 in Hungary is sociologically reasoned by the fact that the idea is, as I have shown, familiar to many of us who remember the times before the democratic change of 1989.