A. Introduction

The European Union (EU) has been confronted with an increasing number of crises in recent years. The ongoing pandemic dominates news headlines but it has merely displaced other prominent issues. The ongoing undermining of its founding values remains the biggest internal challenge to the EU. Hungary’sFootnote 1 and Poland’sFootnote 2 efforts to subvert the rule of law and democracy have grown into a well-known saga. In response to these developments, legal action to address rule of law backsliding in the EU has become more effective and legal scholarship more extensive.Footnote 3 Regulation 2020/2092 now authorizes the European Commission to suspend payments to Member States that “breach the principles of the rule of law”Footnote 4 and the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has permitted non-compliance with the European Arrest Warrant (EAW) Framework in individual cases if there are sufficient rule of law concerns.Footnote 5 However, the established narrative of the Commission enforcing the founding values against recalcitrant Member States is increasingly being challenged. The CJEU recently examined and ultimately rejected Hungary’s challenge of the Parliament’s resolution triggering Article 7 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) on the ground that it violated inter alia the founding value of democracy.Footnote 6 The Parliament itself has initiated legal action against the Commission for failure to take action under Regulation 2020/2092.Footnote 7 The Regulation has, in turn, been challenged by Poland for violating the rule of law.Footnote 8 Despite these events, scholarship remains largely focused on the established narrative. The legal framework supporting and surrounding the founding values remains underdeveloped as a result.

This article undertakes a general review of the role of the founding values in the constitutional framework of the EU and how they should be classified, defined, and enforced. The article’s structure reflects this. It first approaches the founding values from the theoretical angle before addressing the issues surrounding enforcement. The founding values are autonomous concepts of EU law that enable and legitimize the EU legal order. They enable pluralism in the EU by connecting diverging actions to the same roots. Against this backdrop, this article addresses the ambiguity as to whether the founding values are in fact principles and directly enforceable. It will be argued that the founding values have a value and a principle-dimension that are equally important. Direct enforcement is rejected for being doctrinally and normatively unsupported. Instead, the founding values can be sufficiently enforced through binding Treaty provisions and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFREU). Subsequently, this article considers the enforcement mechanisms against the EU and Member States, as well as the risk of subversive legal action by recalcitrant Member States.

B. The Founding Values in (Constitutional) Context

The origins of the founding values have been discussed elsewhere.Footnote 9 Here, a brief sketch will suffice. Klamert and Kochenov suggest that the founding values have been at the center of the EU legal order since its inception.Footnote 10 Walter Hallstein offered an initial list of Grundwerte (core values) in 1969. With peace as its Leitmotiv, it included unity, equality, freedom, solidarity, welfare, progress, and security.Footnote 11 The rule of law was explicitly recognized as a founding value by the CJEU in 1986.Footnote 12 The current list of values was first compiled as the Copenhagen Criteria in 1993.Footnote 13 Today, the founding values are enshrined in Article 2 of the TEU.Footnote 14 The founding values are not merely aspirational statements—leftover trimmings from the failed Constitutional Treaty. Neither are they mere gatekeepers of membership. Instead, the founding values establish the foundation of the European Union. They are “legally binding norms of reference for the joined self-affirmation of the EU” and fulfill three functions. The founding values legitimize the EU, simplify coordination between its members, and safeguard the Union’s effective functioning.Footnote 15

Any interpretation of the founding values must contend with three main issues. First, the extent to which the founding values have attained autonomy under EU law and whether their link with their domestic origins endures. This determines how the constitutional traditions, identities, and values of the Member States impact the interpretation of the EU founding values. Second, whether the founding values produce normative effects by themselves, or whether they can only apply in conjunction with more concrete Treaty provisions that implement them. Third, the effects of the direct or indirect enforcement of the founding values on the EU legal order. Here, we will focus on the first two issues. The third will be discussed later in this article.

I. Autonomous Values

We will begin by addressing the first issue. On the one hand, the CJEU has emphasized that the EU’s unique constitutional framework “encompasses the values set out in Article 2 TEU.”Footnote 16 On the other hand, however, there is no doubt that the founding values are common to the Member States and the product of an overlap between their legal orders.Footnote 17 The question is how firmly the values remain rooted in the constitutional orders of the Member States. This is a question of degree between two extremes: the founding values as the smallest common denominator that all Member States converge on (intergovernmental) or as detached and autonomous concepts of EU law (supranational).

The former end of the spectrum emphasizes the domestic roots of the founding values and focuses on Articles 2(2) and 49 TEU. The differing understandings between the Member States of the founding values overlap and the intersecting set defines their content at the European level and in EU law. This understanding focuses on diversity and reflects the original intention behind Article I-2 of the Constitutional Treaty: that it should “only contain a hard core of values.”Footnote 18 In practice, the content of each founding value could then be determined through a comparative analysis.Footnote 19

At the other end of the spectrum, the emphasis is on the “Europeanness” of the founding values and the autonomy of the EU legal order. Since Article 2 TEU makes no express reference to the legal orders of the Member States for guidance, the values must be given “an autonomous and uniform interpretation throughout the [EU].”Footnote 20 The analogy with fundamental rights is obvious and flows naturally from the CJEU’s understanding that EU law “stems from an independent source of law.”Footnote 21 The content of the founding values may be equally “inspired by [common] constitutional traditions” of the Member StatesFootnote 22 and by the nature and identity of the EU, its aims, and its competences. The autonomy of the EU legal order acts as a valve that permits the influx of foreign legal concepts into the EU legal order but prevents external review.Footnote 23 The autonomy of the values is unaffected by their commonality to the Member States.Footnote 24 Even if the Court references domestic constitutional law, it asserts an autonomous concept of EU law.

The CJEU’s overall understanding of the EU legal order strongly suggests that the “Europeanness” and autonomy of the founding values have priority; they may form part of a nascent European identity.Footnote 25 The roots of the values in the common constitutional traditions of the Member States are merely one source that shapes their content.Footnote 26 This is systemically and teleologically justifiedFootnote 27 and normatively desirable. The founding values can only constitute an effective common standard if they are defined independently. The ongoing rule of law backsliding would be exacerbated if the content of the founding values were overly dependent on their understanding by the Member States. Recalcitrant Member States have already “found the interrelated concepts of constitutional pluralism and constitutional identity particularly helpful as they give a veneer of conceptual respectability to their autocratic ‘reforms’.”Footnote 28 They could frame their subversive measures as different, but equally legitimate, interpretations of the same values. Whenever domestic constitutional traditions are taken into account to interpret the founding values, the emphasis should thus be placed on the common understanding of these values and the non-regression obligation.

II. Values, Cooperation, and Legitimacy

The importance of autonomous values becomes further apparent when we consider their role in the EU legal order. Calliess argues that the founding values have gradually crystalized through the process of integration, because they are “necessarily common to the Member States.”Footnote 29 They are indispensable for the existence of the EU legal order.Footnote 30 This is reflected in the case law on mutual recognition. The principle originates in internal market lawFootnote 31 and now applies across the EU legal order—most prominently in the field of law enforcement cooperation.Footnote 32 Mutual recognition requires “Member States’ actors … to accept and enforce standards and/or judicial decisions made in other Member States.”Footnote 33 This is possible only because these standards and decisions are ultimately based on the same values.Footnote 34 Any divergence and disagreement between the Member States takes place within the same boundaries set by common values; based on their common commitment, the Member States can agree to disagree.Footnote 35 The founding values enable and shape the EU’s pluralist identity as a result; they create unity where necessary and operationalize diversity where possible. This identity is fostered through external differentiation from states and organizations that do not share or respect these values.Footnote 36 Yet, this is only sustainable if the founding values are asserted and upheld against challenges from within.Footnote 37 This leads us to the questions of formal and substantive enforceability, which we will discuss further below.

First, however, we must consider the legitimizing function of the founding values. The values strengthen output and throughput legitimacy by providing a normative baseline, shaping aims and outcomes of EU lawmaking as well as the means by which they are realized.Footnote 38 Whilst plausible and important, this narrative is also dominated by functionalist connotations. The founding values are reduced to mere means, not pursued as ends in themselves. One might cynically claim that they follow EU fundamental rights, becoming means that compensate for the democratic deficit but are unable to remedy it. Without an intrinsic commitment to the values themselves, nothing prevents them from being hollowed out so long as the superordinate end does not collapse.Footnote 39 This risk is amplified if the end itself becomes increasingly vague and uncertain.Footnote 40 The problem can be overcome by committing to the intrinsic importance of the founding values and connecting them to the EU’s “raison d’être.”Footnote 41 Since these values stem from common traditions of the Member States, their inherent desirability should be uncontroversial.Footnote 42 The founding values should join peace, security, and prosperity as the ideals for which the EU stands. Pursuing them in internal and external action would greatly strengthen the EU’s legitimacy in the absence of proper democratic input legitimacy.

C. Classifying the Founding Values

The debate around the classification of the founding values concerns whether they are in fact principles and thus enforceable. We will engage with this question below by offering terminological and substantive clarifications. First, however, let us make some general observations. The founding values are part of the EU Treaties and bind the Member States and the Institutions.Footnote 43 The binding effect on the Member States becomes apparent when the provision is read in conjunction with other provisions of the TEU. Article 49 requires any acceding state to respect the EU’s founding values.Footnote 44 The CJEU recently confirmed that this commitment is subject to non-regression,Footnote 45 which aligns with the principle of sincere cooperation. The values also bind the EU and its Institutions. The very idea of founding values means that the Institutions that form part of it cannot act contrary to them. This is affirmed by Articles 3(1) and 13(1) TEU.

I. Values or Principles?

The question of what kind of norms the founding values are, and whether they are enforceable, remains open, however. Terhechte argues that values are not justiciable by their very nature.Footnote 46 Itzcovich expresses similar concern, arguing that “courts enforce laws, not values …. [and] [i]n order for values to be properly ‘enforced’ … they should first be transformed into valid laws.”Footnote 47 Their justiciability would be tied to their implementations. Kochenov bypasses Terchechte’s and Itzcovich’s concerns by arguing that the founding values are in fact legal principles.Footnote 48 This is the original designation that was used in the Treaty of Amsterdam.Footnote 49 Calliess agrees, noting that “qua content, the [founding] values represent (constitutional) principles, that, dogmatically, create structural requirements and optimization requirements.”Footnote 50 This classification is echoed by other scholars either explicitly or implicitly.Footnote 51 It would justify the immediate enforceability of the founding values by giving them a widely recognized legal characterFootnote 52 and pave the way for their standalone application, which can be justified by reference to the doctrine of effet utile.

The case law does not definitively settle whether Article 2 TEU contains values or principles. Advocate General (AG) Pikamäe has argued against the standalone applicability of Article 2 TEU, but acknowledged that it is widely regarded as possible.Footnote 53 By reference to the old Article 6(1) TEU, the Court rejected the possibility that certain Treaty provisions could “authorise any derogation from the principles of liberty, democracy and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.”Footnote 54 In LM Footnote 55 , however, the Court refers to both “the values common to the Member States set out in Article 2 TEU”Footnote 56 and “the principles set out in Article 2 TEU.”Footnote 57 Similarly, in the recent Hungary v. Parliament Footnote 58 judgment, the CJEU noted that “the principle[s] of democracy and … equal treatment … are values on which the European Union is founded.”Footnote 59 This suggests that the Court does not consider the terminological distinction legally significant.

There are, however, several cases that support the position that the founding values must be implemented in primary or secondary law before they unfold their legal effect.Footnote 60 This likens Article 2 to Article 3(1), which cannot be applied independently of the Treaty provisions that give more specific effect to it.Footnote 61 The provision through which Article 2 can be invoked must therefore be sufficiently specific. Article 19(1) TEU is the most prominent example of such an implementing provision.Footnote 62 This argument runs parallel to two related aspects of EU law: direct effect and, confusingly, the distinction between rights and principles in Article 52(5) CFREU.Footnote 63 The founding values themselves are not sufficiently clear, precise, and unconditional to be invoked directly, but can only be enforced indirectly through Treaty provisions that are. They take effect by excluding certain interpretations and requiring others.

II. On Values as Principles

Proponents of direct enforcement imply that the founding values are Alexian principles.Footnote 64 These guide the interpretation of legal norms and the exercise of executive and legislative powers.Footnote 65 As “optimisation requirements,” they require that an end is realized to the greatest possible extent given the available legal and factual means. Principles act as “positive shapers and negative constraints” in the lawmaking context.Footnote 66 They are not binary standards but can be fulfilled to various degrees.Footnote 67 Principles can be weighed against each other when they conflict, and one can take precedence without the other becoming invalid.Footnote 68 This description fits the EU’s founding values well. It is evident that “democracy,” “equality,” or “freedom” can be realized differently without being challenged.Footnote 69 Democracy in the EU is a prime example. The discussion of the democratic deficit has featured prominently throughout the EU’s history. We can certainly argue that reforms could make the EU more democratic. Yet, it is hardly tenable to argue that the EU is fundamentally undemocratic. We can also argue about whether the EU guarantees equality sufficiently and whether freedom should be curtailed to increase it. We cannot convincingly claim that the EU is truly unequal or unfree. Principles must be realized to the greatest possible extent, but they do not create absolute or unconditional requirements. The founding values shape the creation of new EU laws and the interpretation of existing ones; both functions are governed by a balancing of competing interests. This can take place intra-value, when implementations of the rule of law balance procedural fairness against efficiency, for example, or inter-value, when democracy and freedom (of speech) collide with each other.Footnote 70 The benefits of balancing are apparent. It is an intuitive and transparent approachFootnote 71 that enables a high degree of flexibility and fairness whilst taking into account factual and legal constraints.Footnote 72

Yet, balancing also has its drawbacks. It makes promises of precision and objectivity that cannot be kept.Footnote 73 There is also uncertainty about which competing interests can impose limitations on the founding values.Footnote 74 This is an important consideration because competing interests equip recalcitrant Member States with grounds for justifying subversive measures. It could, of course, be argued that the founding values can only be restricted by reference to each other. This would undoubtedly safeguard the values but it would also be impractical. For example, none of the founding values justify the limitations imposed on the free movement of economically inactive EU Citizens, which are arguably restrictions of freedom and equality.Footnote 75 Allowing a wider range of countervailing interests appears necessary, but where should the limits be drawn?Footnote 76

III. Over-Constitutionalization

This leads us to the underlying problem of over-constitutionalization. There are two dimensions to this problem. First, making the founding values directly enforceable would increase the scope of application of EU law. The founding values underpin the functioning of the EU legal order and must continuously be upheld by the Member States. Thus, any measure that relates to the content of a founding value and is liable to affect the functioning of the EU legal order would fall within the scope of application of EU law. Second, the norms that are tied to the founding values are infused with their constitutional status. Any legal problem that is linked to the founding values can eventually be reduced to an issue of balancing these values against each other or competing interests.Footnote 77 This would inevitably degrade the special status of the founding values and undermine the idea that they represent a “hard core of values.”Footnote 78 Overall, directly enforceable values would increase the depth and width of constitutionalization in the EU. They would further rigidify EU law because, as Grimm notes, “the more ordinary law is regarded as constitutionally mandated, the less politics can change it if this is required by the circumstances or by a shift of political preferences.”Footnote 79 Evermore emphasis would be placed on the Commission and Court as the non-negotiable extent of EU law is increased.Footnote 80 Ironically, these are the exact issues that gave rise to the proposals for the direct enforceability of the founding values in the first place. The failing of Article 7 TEU and the lack of a flexible yet effective political remedy—as well as the legitimacy threat posed by rule of law backsliding—have already put the ball squarely in the Commission and CJEU’s court.

We can only resolve this conundrum by accepting that, sometimes, less is more. Rather than expanding the scope of the founding values, we should explore their links with the remainder of the acquis. After all, it is well-established that “in all situations governed by European Union law,” the Member States must have due regard to its rules.Footnote 81 The acquis should be interpreted in accordance with the founding values whenever they are relevant, enforcing them indirectly. In turn, interpretations of Article 2 TEU should be minimalistic and limited to the very foundation upon which the EU operates.Footnote 82 Doing so minimizes the risk of overloading the founding values with content and subsequent over-constitutionalization. It becomes possible to allow only those limitations that the founding values impose on each other without undermining their operability. Indirect enforcement also ensures that their intrinsic worth is not overshadowed. The fact that the Member States have committed themselves to these values voluntarily and out of their own volition should be emphasized. This can only be meaningful, however, if the Member States and Institutions can jointly shape the founding values and thereby affirm their commitment to them—not out of necessity, but out of conviction. The Court’s definitions of the founding values must be clear and precise to enable such a discourse, but not tie them directly to the functioning of the EU legal order, and thereby set them in stone.

This approach resolves the false dichotomy between principles and values that results from their blurred boundaries in the constitutional context of Article 2 TEU. Let us briefly step back into the realm of legal theory to clarify this: Alexy distinguishes values and principles as axiological and deontological, respectively.Footnote 83 Values express what is best (preference), while principles express what ought to be (obligations).Footnote 84 This distinction is clear at the abstract level, but easily muddled when applied to constitutional provisions. When the Treaties subscribe to human dignity, freedom, democracy and so forth as preferences, they become fixed and binding, imposing obligations.Footnote 85 Thus, through constitutionalization, the founding values also express principles. Recent case law emphasizes the principle-dimension of Article 2 TEU by focusing on its role in operationalizing the EU legal order. This is the functional, top-down interpretation of the principle-dimension.Footnote 86 But a normative, bottom-up perspective is equally valid. All Member States share the common values and therefore have sufficient mutual trust to create a common legal order. This emphasizes the value-dimension of Article 2, the prior and voluntary commitment to the founding values for their intrinsic worth.Footnote 87 These two dimensions are complementary, not in competition. Indirect enforcement safeguards the functional importance of the founding values without overshadowing their inherent desirability.Footnote 88 We do not endanger the enforcement of the founding values by limiting ourselves to indirect enforcement. As we will see, the Treaties and Charter offer a broad range of provisions through which the founding values can be enforced under the existing enforcement mechanism.

D. Enforcing the Founding Values: Content

Defining the content of the founding values is paramount, regardless of whether they are directly enforceable or not, to clarify the requirements they impose on the Institutions and Member States.Footnote 89 It follows from the foregoing Section that any definition of the founding values for the purposes of enforcement should follow the guiding principle of essentialism.Footnote 90 Their autonomous content must be limited to what is essential for the foundation of the EU legal order. Their content can then be derived from three main sources. First, the content of the founding values is shaped by their role in operationalizing the EU legal order. The CJEU has already used this approach in the context of the rule of law to identify that it entails effective judicial protection.Footnote 91 This derivation should be shaped by the Treaty provisions that operationalize the EU and its Institutions. Second, EU fundamental rights also shape the founding values.Footnote 92 It is evident that there is considerable overlap between Article 2 TEU, the Charter and its Explanations,Footnote 93 and the general principles of EU law. The Court has already recognized the link between the right to effective judicial review and the rule of law, specifically the requirement of judicial independence.Footnote 94 However, the CJEU has limited this link to the essence of fundamental rights, which is the minimal subset of the right required for its meaningful enjoyment.Footnote 95 This limitation is justified in light of the principle of essentialism, and avoids overloading the content of the founding values. Finally, the requirements imposed on candidate states by reference to Article 2 TEU also offer insights into the content of the founding values, as does the Commission’s review of compliance therewith. Since the Member States cannot regress from the founding values after accession,Footnote 96 these requirements must necessarily reflect their common standards. Beyond these three main sources that are internal to the EU legal order, there are also external ones: the constitutional traditions of the Member States, the work of the Venice Commission, and the case law of the ECtHR.

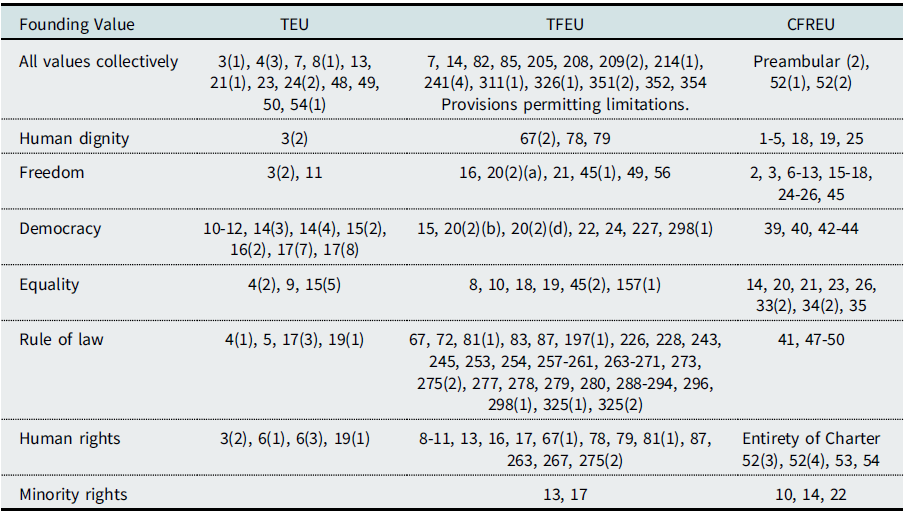

Based on these sources, we can compile a tentative sketch of the content of the founding values and their links with other provisions of EU law through which they can be enforced.Footnote 97 It is obvious that human dignity corresponds to Article 1 CFREU but it is also linked to the prohibition on torture in Article 4 of the Charter.Footnote 98 Even though both rights are absolute,Footnote 99 a violation of either right would only translate into a violation of Article 2 if it resulted from systemic disregard for human dignity.Footnote 100 Examples could be the failure to address the widespread use of torture by law enforcement, or authorizing the use of lethal force against hijacked vehicles with innocent passengers onboard.Footnote 101

The founding value of freedom embodies the rejection of tyranny and embrace of individual autonomy. This value has rarely been referenced in CJEU case law, even though it can be associated with several groups of fundamental rights. First, this includes the freedoms of thought, conscience and religion, expression,Footnote 102 and assembly—found in Articles 10–12 CFREU—which are closely related to each other.Footnote 103 According to the Venice Commission, the core obligations of states include the “presumption in favor of (peaceful) assemblies” as well as “positive obligation[s] to facilitate and protect” the exercise of the right to assembly.Footnote 104 Non-interference with the “freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas” is equally critical.Footnote 105 Second, freedom also relates to the right to private life and the protection of personal data. The Court has ruled that the general surveillance of the content of personal communications would violate the essence of these rights.Footnote 106 Such a measure affects society at large and would impinge on Article 2 TEU. Third, freedom also relates to the free movement of persons. The case law has clarified that broad expulsion policies against EU Citizens violate the essence of their rights.Footnote 107 Such measures would interfere with Article 2 TEU if they are the result of general legislation. Finally, freedom can also be linked to economic rights, including the freedom to choose a profession, conduct a business, and the right to property (Articles 15-17 CFREU). The CJEU has, however, interpreted their essence very narrowly,Footnote 108 which suggests that only the most severe systemic interferences could violate Article 2 TEU.

The case law relating to democracy offers comparatively more guidance. It has explicitly been linked to Articles 10(1) and 14(3) TEU and European representative democracy.Footnote 109 The Court’s emphasis on universal suffrage and free, secret, and regular elections resembles Article P1-3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the recommendations of the Venice Commission.Footnote 110 Democracy also requires that elections are effective and capable of causing a change in government.Footnote 111 This value is further linked to the civil rights associated with EU Citizenship. The Court has also linked democracy to the rights that enable it, particularly the freedom of expression.Footnote 112 This indicates that the scopes of the founding values are not separate but that they can overlap.

Equality is similarly reflected in a broad range of Treaty and Charter provisions. This includes Articles 9(1) TEU and 18 TFEU, as well as Article 20, and the remainder of Chapter III CFREU.Footnote 113 Guidance from the case law is, however, scarce. The key challenge in defining the content of the founding value of equality is accommodating a wide array of countervailing interests. Currently, the value seems to be restricted to precluding direct and systemic discrimination. Equality also applies among the Member States (Article 4(2) TEU) and the EU’s institutional setup.Footnote 114

Guidance on the rule of law abounds by comparison, given that it is the founding value that has featured most prominently in the Court’s case law so far. The CJEU has explicitly linked the rule of law to Article 19(1) TEU and concretized the requirements of judicial independence and impartiality.Footnote 115 The Venice Commission has also engaged with the value in depth, adding four more requirements that are reflected in EU law:Footnote 116 Legality;Footnote 117 legal certainty;Footnote 118 non-arbitrariness;Footnote 119 and fair trials.Footnote 120

The last founding value is significantly broader in scope than the others. Respect for human rights and the rights of minorities does not refer to specific individual rights but to the entire fundamental rights canon. This includes the Charter as a wholeFootnote 121 and Article 6 TEU. This broad scope—read in light of the CJEU’s systemic approach—suggests that it would only be violated by shortcomings, such as the ones envisioned by the German Constitutional Court in Solange II Footnote 122 or the ECtHR in Bosphorus.Footnote 123

We have now established an initial list of what the founding values mandate and how they are connected to the remainder of the acquis. A complete overview is included at the end of this article. This leaves us with the question of the threshold for a violation. The case law suggests that the Court roughly follows Scheppele’s proposal for “systemic infringement actions.”Footnote 124 Compliance with an extradition request under the EAW Framework can only be refused where there are systemic or generalized deficiencies in the independence of the judiciary in the requesting state.Footnote 125 The severity threshold resembles that of Article 7 TEU, which requires “a serious and persistent breach.”Footnote 126 The Commission’s annual rule of law report will likely play a key role in establishing the factual basis for procedures alleging such deficiencies, regardless of whether they are brought by the Institution itself or third parties.Footnote 127 This may pave the way for the use of other soft law mechanisms as precursors to hard law enforcement for the other founding values, and increase the weight of those soft law mechanisms in return.

Guidance on the “systemic or generalized” threshold remains limited. With regard to the irremovability of judges, the Court has required any limitations to judicial independence to be based on legitimate and compelling grounds and to respect the proportionality principle.Footnote 128 The rules on the appointment and removal of judges must “dispel any reasonable doubt in the minds of individuals as to the imperviousness of that body to external factors and its neutrality with respect to the interests before it.”Footnote 129 It is true that the CJEU does not mention the “systemic or generalized” standard in several cases on the rule of law and judicial independence. However, it is crucial to take the nature of the measures at stake in these cases into account. Given that the deficiencies were the result of sweeping judicial reforms, they are necessarily either systemic or general.Footnote 130 Thus, individual shortcomings cannot amount to violations of the founding values unless they are part of wider systemic or generalized patterns. An individual interference with the essence of a fundamental right is not automatically a violation of the corresponding founding value. While systemic or generalized deficiencies in the respect for a founding value imply a violation of the essence of a connected right, this does not apply viceversa.Footnote 131 However, this also raises a delimitation problem: where should the boundary be drawn between multiple individual violations and a systemic one? The CJEU has so far left it to the domestic courts to determine whether there are systemic or generalized deficiencies in a given case. This approach avoids categorical findings, respecting the role of Article 7 TEU, and the final step in creating a judicial alternative to the political sanctioning procedure provided for in the Treaties.Footnote 132

E. Enforcing the Founding Values: Procedures

The final part of this article will discuss the different routes for enforcement against the Member States and the EU Institutions. It also considers the defense of constitutional identity and the question of domestic review. The findings made below apply regardless of whether the founding values are directly or indirectly enforceable.

I. Enforcement against the Member States

1. Direct Enforcement at EU level

There are two ways of looking at the enforcement of the founding values through infringement actions. We can either object to it as an improper means that circumvents the purposefully high threshold of Article 7 TEU, or we can accept it as a means to preserve the effectiveness and unity of Article 2 TEU.Footnote 133 The latter perspective is warranted in light of the function of the founding values that we explored above. They underlie, uphold, and enable the EU legal order and, as such, permeate it entirely. Limiting their relevance to Article 7 TEU would disconnect the values from most of the Treaties and undermine their legitimizing effects.

The Commission’s infringement proceedings against Member States under Article 258 TFEU for failure to uphold the founding values should thus be welcomed.Footnote 134 Article 2 TEU has so far featured in an ancillary function in these proceedings, guiding the interpretation of the Treaty and Charter provisions whose infringement the Commission alleged. The founding values have also been raised in a case between Slovenia and Croatia that was brought under Article 259 TFEU. It concerned arbitration proceedings regarding a border dispute between the two countries.Footnote 135 Slovenia claimed that Croatia’s rejection of the arbitration award was in violation of the rule of law and had breached Article 2 TEU by itself.Footnote 136 The issue was never addressed substantively, however, because the case failed on jurisdictional grounds.Footnote 137

These cases reiterate the importance of clarity regarding the scope of the founding values. While it is easily argued that deficiencies in the judicial system fall within the scope of EU law through Article 19(1) TEU,Footnote 138 the boundaries are less clear in other contexts. Could executive regulation and decision-making be reviewed under EU law if it sidelines national parliaments too much? Similarly, it is clear that democratic shortcomings in the elections to the European Parliament would be reviewable under Article 14(3) TEU, but does EU law also extend to domestic elections if they risk undermining the indirect democratic legitimacy of the Council?Footnote 139 The challenge is again one of balance. Enforcement must be broad enough to safeguard the effectiveness of the founding values and the legal order they enable, but also specific enough to be foreseeable, and leave room for diversity among the Member States.

AG Bobek’s recent opinion on Article 19(1) addresses this tension through a reverse solange approach. Through that provision, the CJEU should address “only [shortcomings] of a certain gravity and/or of a systemic nature, to which the internal legal system is unlikely to offer an adequate remedy.”Footnote 140 The onus is foremost on the Member States, which must have systems in place to correct even the most severe and systemic deficiencies with regard to the founding values.Footnote 141 There is a presumption of compliance and the CJEU intervenes only when this is refuted by the fact that the domestic system is incapable of upholding its commitment to the founding values. This is a largely pluralistic approach that favors decentralized review and emphasizes the commonality of the founding values. It also leaves room for enforcement of the founding values for their own sake by prioritizing domestic review, whilst recognizing the importance of CJEU review as the ultima ratio.

2. Indirect Enforcement through Domestic Actions

Individuals have already brought cases alleging breaches of the founding values in domestic courts. In fact, the CJEU first considered the link between Articles 2 and 19(1) TEU in a preliminary ruling.Footnote 142 Issues regarding judicial independence have featured prominently in preliminary references since, usually in the context of the EAW Framework. Above, we noted that courts can decline extradition where there are systemic deficiencies regarding judicial independence in the requesting state on a case-by-case basis.Footnote 143 The CJEU also confirmed that Article 19(1) TEU has direct effect.Footnote 144 It can be invoked directly before domestic courts in order to review the independence and impartiality of the domestic judiciary,Footnote 145 enabling indirect review of Article 2 TEU. This reasoning could easily be extended to the aforementioned Article 14(3), for example. There is, however, no ruling on the direct effect of Article 2 TEU itself. The Court’s case law on Article 3(1) TEU suggests that such a finding is unlikely.Footnote 146 If the generality of the EU’s objectives precludes it from having direct effect, the same arguably applies to the founding values.

The case law on the rule of law and judicial independence suggests that the standard for review does not differ between infringement actions and preliminary references. Instead, the Court’s focus shifts depending on the facts of the case before it. A distinction should be made based on whether the case concerns a general measure or individual decision. In the former type of cases, the question of whether a founding value has been violated is central. Insofar as these cases focus on general reforms, the severity and justifiability of the limitation is central. By contrast, measures concerning individual decisions only seek the annulment thereof. The question of whether a founding value has been violated is merely a means to that end, which can also be achieved by establishing another sufficiently serious violation or risk thereof.Footnote 147 These cases are not about correcting systemic issues, but about protecting the rights of a specific individual.Footnote 148

3. Constitutional Identity

The final issue in enforcing the founding values against the Member States is the role of Article 4(2) TEU.Footnote 149 Although constitutional identity and the founding values have not yet clashed before the CJEU,Footnote 150 this is only a question of time. Poland has already invoked its constitutional identity in a white paper justifying its judicial reforms.Footnote 151 A joined reading of Articles 2 and 4(2) TEU, however, reveals that the former cannot override the latter.Footnote 152 The founding values are the basis for the EU legal order and enable its continued functioning. Constitutional pluralism in the EU is conditional on common respect for these values. They define the limits within which Member States can agree to disagree.Footnote 153 Respect for constitutional identity is therefore a requirement under, not an exception to, the EU’s founding values.Footnote 154 This is supported by the autonomy of the EU legal order and its founding values. Their meaning and what they require are determined solely by the CJEU, independently from the Member States.

There remains an underlying issue, however. The problem inherent in MacCormick’s “radical pluralism” also hangs above conditional pluralism like the sword of Damocles. MacCormick found that pluralism would inevitably end up at an impasse where the highest domestic courts refused to submit to the CJEU when interpreting their respective constitutions and the CJEU would do the same with regard to the interpretation of the Treaties.Footnote 155 Legally, this could only be resolved through recourse to an external mechanism.Footnote 156 In the context of conditional pluralism based on the founding values, we would arrive at an impasse when the CJEU and a domestic court disagreed over whether a given founding value had been infringed, due to different understandings of the content of that value. Neither Court could accept the other’s interpretation.

As a result, even conditional pluralism remains vulnerable to abuse by recalcitrant Member States. Hungary v. Parliament heralds this risk.Footnote 157 As we shall see at the end of the next Section, the ultimate legal solution to this problem can only be the rejection of pluralism in favor of a clear hierarchy. However, this is not a foregone conclusion. Through the controlled operationalization of review of EU law against the founding values, the conflict that would eventually result in the assertion of primacy can be avoided.

II. Enforcement against the EU Institutions

The Institutions’ competences flow from the Treaties and must be interpreted and applied in accordance with the founding values, even when acting outside the scope of EU law.Footnote 158 Article 10(1) specifies that the “institutional framework … shall aim to promote [these] values”Footnote 159 and Article 13(2) obliges each Institution “to act within the limits of the powers conferred on it in the Treaties, and in conformity with the … objectives set out in them,” which include the founding values.Footnote 160

1. Annulment of EU acts

EU legal acts can be challenged for violations of the founding values under the established procedure of Article 263 TFEU as “infringements of the Treaties.”Footnote 161 The founding values have recently been the object of Hungary’s challenge to the Parliament’s resolution that initiated proceedings against the former under Article 7 TEU. Hungary alleged that the vote on the resolution infringed the founding values of democracy and equality because abstentions were not counted. The Grand Chamber only applied these values indirectly through the interpretation of Article 354 TFEU, which sets out the voting requirements for the Parliament. It did not examine whether the Parliament violated the founding values themselves.Footnote 162 This is in line with the ancillary role that the values have played in other cases. The General Court has referenced democracy when annulling a Commission decision refusing to register a European Citizens’ Initiative.Footnote 163 It has similarly drawn on the rule of law to restrict anti-corruption measures under the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) to acts that “undermine the legal and institutional foundations of the country concerned.”Footnote 164 The latter two cases raise questions about the standard that applies to interferences with the founding values. The former suggests that a violation can be found quite readily, whereas the latter implies that the obligations imposed by the founding values themselves are narrower. Review against the founding values is also possible through preliminary references in domestic proceedings. However, the questions referred to the CJEU rarely raise direct violations of Article 2 in cases against EU law.Footnote 165 In Pringle, Footnote 166 the European Stability Mechanism was challenged inter alia by reference to Articles 2 and 3 TEU, but these grounds were declared inadmissible by the Court.Footnote 167

Lastly, we must take note of the risk of abuse. As noted above, Hungary has sought to turn the value of democracy against the European Parliament’s Article 7 Resolution.Footnote 168 Regulation 2092/2020 has similarly been challenged by reference to Article 2 TEU and the rule of law in particular.Footnote 169 A recent case brought by Romania alleges that the registration of a European Citizens’ Initiative on minority rights violates the founding value of equality. It also entails a potential conflict between said value and that of the protection of minority rights.Footnote 170 These cases highlight the need for a restrained approach to the founding values to avoid a litigation drive that could increase over-constitutionalization.

2. Failure to act

The EU Institutions could also be indirectly responsible for breaches of the founding values by the Member States. This primarily affects the Commission, which is under the duty to ensure the application of the Treaties (Article 17(1) TEU), including the founding values and the provisions that implement them. Failure to do so may expose the Commission to action under Article 265 TFEU. In light of the European Parliament’s (EP) Resolution of March 25, 2020, this is no longer legal fiction. The Resolution calls on the Commission to act upon its 2020 Rule of Law Reports by initiating sanctions under Regulation 2020/2092 by June 1, 2021.Footnote 171 Following the Commission’s failure to do so, the Parliament initiated legal proceedings through an action brought on October 29, 2021.Footnote 172 The Parliament claims that the Commission has violated its duty to ensure the application of the Treaties (Article 17(1) TEU) in conjunction with Article 6 of Regulation 2020/2092, its duty to act independently (Article 17(3)), as well as the principles of institutional balance and mutual sincere cooperation (Article 13(2) TEU).

Following the initiation of proceedings pursuant to Article 265 TFEU, Parliament will have to show that the Commission’s inaction amounts to a “failure to act”—in other words, “failure to take a decision or to define a position.”Footnote 173 This decision must be specific enough so that it could be the subject of an instruction to act under Article 266.Footnote 174 There must also be an obligation to carry out that act. These requirements are arguably met with regard to Regulation 2020/2092. It specifies that measures shall be taken to counteract breaches of the principles of the rule of law, provides an overview of such measures, and specifies the procedure for their adoption.Footnote 175 The EP could argue that, in light of its 2020 Rule of Law Report, the Commission should have moved to take measures under Article 5 of the Regulation against the Member States that undermine the “effective judicial review by independent courts of actions or omissions by the authorities”Footnote 176 in implementing the Union budget. By delaying the potential initiation of proceedings under Article 6 of the Regulation until the CJEU’s ruling on the legality of the Regulation, the Commission has failed to fulfil its obligations under the Regulation and the Treaties.Footnote 177

The CJEU upheld the validity of Regulation 2020/2092 in two judgments on February 16, 2022.Footnote 178 It remains to be seen whether the Commission will now initiate proceedings against Poland and Hungary under the Regulation, and whether this may lead the Parliament to withdraw its application.

3. Values, Primacy, and Domestic Review

We will conclude our analysis by discussing the relationship between the founding values and the primacy principle, with particular focus on the competence of domestic courts to review EU law. The possibility of domestic “value-review” is rooted in Achmea Footnote 179 , where the CJEU recalled the commonality of the founding values and held that this “premise implies and justifies the existence of mutual trust between the Member States that those values will be recognized, and therefore that the law of the EU that implements them will be respected.”Footnote 180 The Court explicitly links the primacy of EU law to the common founding values. First, primacy is justified by the fact that EU law implements and thus respects the common founding values. Second, Member States would contravene the principle of mutual trust and the founding values if they failed to respect primacy by deviating from EU law. This argument is essentially abstracted from Solange II and Bosphorus. EU law enjoys primacy and must not be reviewed or resisted domestically because it is ultimately an implementation of the common values.

This argument can easily be turned into an authorization of “value-review.” However, if the primacy of EU law is based on its compliance with the founding values, should domestic courts not be allowed to review this? The question of primacy is transferred to the most fundamental level of the EU legal order. Arguments in support of “value-review” are easily constructed. An EU legal act that contravenes the founding values lacks legal, political, and social legitimacy.Footnote 181 It must be invalid and inapplicable, and domestic courts must be able to ensure this. Domestic courts that consider that a founding value may have been violated, should, of course, refer the issue to the CJEU for review.Footnote 182 However, issues arise when the EU and domestic courts disagree about the violation of a founding value, particularly because they disagree on the content of that value. We sought to pre-empt this issue above when we argued that Article 2 TEU should be given sui generis meaning by the CJEU. But this may not always be feasible. For example, it is questionable how much room for compromise the German Constitutional Court could accept regarding human dignity. Next to “honest” disputes over the content of the founding values, there is also the risk of abuse. Captured courts could purposefully create conflicting definitions of the founding values to reject the application of EU law or even challenge its validity. We already discussed this problem in the context of constitutional identity, but it is exacerbated here. The rejection of EU law in one Member States would threaten the unity of the entire legal order. The constitutional crisis would be complete.

Whether this issue materializes depends on the balance struck in defining the scope of the founding values. While they enable pluralism by allowing Member States to “agree to disagree,” the founding values also demarcate the boundaries of that disagreement. If these boundaries are challenged, alignment through interpretation is not possible—the functioning of the EU legal order can only be upheld by asserting the primacy of EU law as the ultima ratio.Footnote 183 Calliess argues that primacy should be invoked when the “core” of the founding values is violated.Footnote 184 This is not a desirable solution, because it adds an unnecessary level of complexity and uncertainty to the problem without getting to the heart of the issue outlined above.Footnote 185 It either refers to a subset of the founding values, raising the difficult question of how it should be distinguished, or the minimum of each founding value on which there must be consent for the EU legal order to function, which is difficult to distinguish from the autonomous meaning of the founding values under EU law. It would be better to decouple primacy from the founding values altogether, thereby removing the basis for “value-review.” Primacy should be likened to what Calliess refers to as intrinsic values, values that are of existential importance to the EU legal order and its functioning.Footnote 186 Primacy and the founding values must be co-original and exist at the same level, jointly operationalizing the EU legal order and with neither presupposing the other.

F. Conclusions

The founding values are playing an increasingly prominent role in the EU’s and scholarly responses to rule of law backsliding. They are also increasingly invoked by the recalcitrant states to legitimize their actions or to challenge EU measures targeting them. Yet, the structural role of these values and their legal classification remain debated. The CJEU’s engagement with the founding values has been limited to individual cases and the Court has so far refrained from constructing a systematic framework for their application and enforcement. Against this background, this article has drawn on the existing case law and literature to argue how the founding values should be understood and enforced.

At the outset, we clarified that the founding values do not only legitimize the EU legal order, but also operationalize it by enabling pluralism. Diversity in the EU does not obstruct cooperation because the Member States are united in their common commitment to the founding values.Footnote 187 Disagreement on specific outcomes is possible because these are ultimately different implementations of the same shared values. To preserve this and avoid over-constitutionalization, the direct enforceability of the founding values must be rejected. Such an approach lacks support in the case law as it stands and is normatively undesirable. It would undermine the special status and function of the founding values, ultimately weakening them and the EU legal order and obstructing the realization of the values as such. Subsequently, we rejected the concern that limiting the founding values to indirect enforcement would degrade their effectiveness. The approach currently taken to enforce the rule of law can be transposed to the other founding values as well. The founding values can be enforced indirectly through domestic courts and also against the EU Institutions. In light of the EP’s Resolution of March 25, 2021, we focused on actions for failure to act against the Commission in response to insufficient efforts to safeguard Article 2 TEU. Finally, we addressed the concern that the founding values could be abused by recalcitrant states and justified why these values take precedence over constitutional identity.

As critically important questions about the founding values remain, the need for comprehensive guidance by the CJEU becomes more pressing. If domestic constitutional reforms become subject to scrutiny at the European level, it is paramount that Member States know which standards that have to comply with. Such a shift in approach would also take the wind out of the recalcitrant Member States’ sails by restricting the scope of constitutional identity and ostensible references to the principle of legal certainty.Footnote 188 It would also ensure that the Member States and Institutions can jointly develop the founding values as such, rather than as principles that only serve the functioning of the EU legal order.

G. Addendum: The Links Between the Founding Values, Treaties, and Charter