A. Introduction

It is commonly thought that the Italian system of judicial governance (or at least some of its elements) served as an export modelFootnote 1 to implement the principle of the rule of law in countries transitioning from authoritarian rule. Whatever the reason for this influence might be, one cannot but observe with disappointment the results of this legal transfer in securing a good balance between judicial independence and accountability. To be fair, the cause does not lie in the model itself, but rather probably has something to do with the timing of its incorporation and with its prioritization against other crucial dimensions outside the competence of the judicial council, such as training and recruitment.

Yet, such model has its own weaknesses, and even in Italy, while ensuring an overall higher degree of independence, it has been questioned for propping up an accountability imbalance and a certain degree of inefficiency. Also, the “Palamara affair,” which sparked off in spring 2019, took the lid off a web of across-the-board groups of magistrates, politicians, businessmen, and members of the judicial self-governance body.Footnote 2 At its core, this affair concerned informal talks between two members of Parliament, a former president of the National Association of Magistrates, and three judicial members of the Italian judicial council (Consiglio superiore della magistratura, hereinafter C.S.M.) relating to the appointment of the heads of the Perouse and Rome prosecution offices. This in turn greatly reduced trust in the judiciary and exposed a transparency deficit.

In order to highlight the risks inherent in a system where a body composed of a majority of judges (or magistrates where this applies) holds strong governance powers, this article delves into the informal dimension unveiling the actual dynamics with regard to the Italian case study.Footnote 3 Only an understanding of the informal dimension is indeed able to account for those hidden details that are very much specific to a given legal system, beyond the abstract and fictitious standardization of formal rules. In the Italian case, informal institutions have amplified the corporatist effects stemming from the numerical prevalence of magistrates within the C.S.M.: At least, this is a common view that the present analysis confirms. Yet, this conclusion is only partial, and it would be wrong to portray informal institutions in negative terms only. This article actually argues that the operation of the C.S.M. and the overall legitimacy of the judicial system also benefit from other informal institutions at play.

In order to account for the negative effects of some informal institutions in terms of increased corporatism in the operation of the C.S.M., but also of the positive role other informal institutions play in partly countering such effects, the article unfolds as follow. Section B delves into the operation and the organization of the C.S.M., looking at informal institutions involving the main actors on the stage: Its president and vice-president, its steering committee, its judicial and non-judicial members, and its administrative technostructure. This allows for a proper understanding of the nature of the main judicial self-governance body and of the role the relevant actors play. Section C discusses the informal rules and practices in relation to a judicial career, and, in particular, appointments of court presidents and professional assessment. Here, the contrast between a highly formalized setting and its distortion through informal practices is underlined, as well as the attempt to correct this distortion through further formalization. Section D makes some observations on the relevance of informality and the factors shaping it, articulating the answer to the question about the effect of informal institutions on the judiciary, judicial values, and the quality of Italian democracy.

When referring to informal institutions, the article relies on the existing literature according to which these are “socially shared rules, usually unwritten, that are created, communicated, and enforced outside of officially sanctioned channels.”Footnote 4 For the purpose of this article, these are understood more precisely as non-codified practices among judicial or non-judicial actors, or rules affecting judicial governance or judicial decision-making.Footnote 5 I do not elaborate here on the distinction between rules and practices. A few notes are, however, necessary to delimit the notion of “non-codified” in relation to the case under consideration.

Clearly, codified (or formalized) rules are those set in constitutional documents, acts of Parliament, Government decrees, and regulations. They are also those set in the instruments that express the normative power of the C.S.M.: Its Internal Rules, but also so-called circolari, direttive, and risoluzioni through which the C.S.M. regulates the exercise of its own powers, or regulates the duties of other judicial actors (candidates for appointments, local judicial councils, court presidents).Footnote 6 As a matter of fact, the C.S.M. resorted to these legal instruments to broaden the scope of its competence, encroaching on the powers of Parliament and its reserved legislative domain. This resulted in an established practice that was not contradicted by Parliament and was even conceptualized by some as a constitutional convention but has been criticized by others as contra legem.Footnote 7 It is therefore debated—and the discussion is not settled within Italian legal scholarship—whether the legal rules encroaching on the power of Parliament are a formal source of law or just reflect a practice filling a legal vacuum. While there seems to be a tendency to consider the relevant rules a de facto or administrative practice from a domestic perspective, within the framework of the comparative research endeavor, it is fair to approach it as formal, codified rules.Footnote 8

B. The System of Judicial Governance and the Operation of the C.S.M.

According to formal rules,Footnote 9 the system of judicial governance in Italy is based on a major competence-sharing between the C.S.M. and the Ministry of Justice. The former—a collegial, executive-independent, mixed-composition body—is in charge of carrying out the functions relating to recruitment, appointments, and transfers, promotions, and disciplinary measures.Footnote 10 The latter, the Minister of Justice, bears responsibility for the organization and functioning of those services involved with the administration of justice.

One of the distinctive features of the C.S.M., justifying its creation back in 1946-1947,Footnote 11 is its balanced composition. The C.S.M. is presided over by the President of the Republic—a neutral authority in the Italian system of government—and consists of the First President and the General Prosecutor of the Court of Cassation and of (currently 30) elected members. Of these, two thirds are elected from among ordinary judges by their peers (judicial members: togati) and one third by Parliament from among university professors of law and lawyers with 15 years of practice (non-judicial, lay members: laici).Footnote 12 The Council elects a Vice-president from the pool of members designated by Parliament.

The rationale of this composition is to achieve a reasonable balanceFootnote 13 to avoid both politicization and corporatism, with the Head of State playing a moderating role. The justification of such arrangement is the existence, as for any accountability arrangement aiming at greater independence, of a “system of checks and balances [. . .] which prevents any principal from taking control of the majority of the accountability mechanisms.”Footnote 14 In order to ensure such a balance, the organization of the C.S.M. is highly regulated by lawFootnote 15 and by the C.S.M.’s Internal Rules. The need for regulation—which is a characteristic of the Italian legal culture—is grounded on the premise of the impossibility of relying solely on the goodwill of the relevant actors. Nevertheless, legal rules have gaps and ambiguities that allow for some variance in the actual power relations among the different actors within the C.S.M., while the inherent flexibility of the institutional arrangement opens the way to informal dynamics.Footnote 16

In the next sections, the question I address is: How do informal institutions affect such rationale of a “rule-of-law authority” grounded on a delicate “accountability balance”?Footnote 17 To address this question, to which I will return in the concluding paragraph, I consider three dimensions. The first one relates to the steering of the C.S.M., and therefore to the informal rules and practices relating to its President and Vice-president and to the Steering Committee. The second one relates to the fundamental dynamics in the decision-making process, mostly focusing on the role and status of elected judicial and lay members of the C.S.M. Then, the third dimension concerns the informal rules and practices regarding the C.S.M.’s administrative technostructure—a dimension almost completely neglected in the literature on judicial councils.Footnote 18 As it hopefully appears from the analysis, the common thread of these three dimensions is the interplay between the major influence of judicial actors and the “resistance” by other actors against such influence.

I. Steering the C.S.M.

Literature on judicial councils and supranational policy documentsFootnote 19 often emphasize councils’ overall composition, ignoring their institutional steering arrangements.Footnote 20 This is, however, a relevant dimension for the Italian C.S.M., governed by the interplay of (1.) its President, (2.) its Vice-president, and (3.) its Steering Committee. The actual role of these three actors becomes apparent only when one looks at the relevant practices and relativizes the straightforward view of a purely corporatist system.

1. Who Chairs the C.S.M.? The Invisible Presence of the Head of State

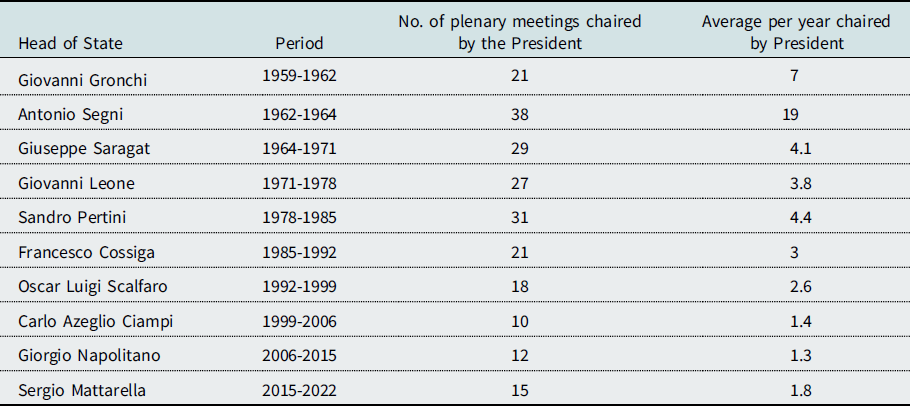

The Constitution assigns to the Head of State the role of President, and the role of Vice-president to a lay member chosen by the C.S.M. Since the very beginning, it has become a practice for the Vice-president to replace the President at most of the meetings, due to the actual impossibility for the Head of State to engage in the C.S.M.’s daily activities. This practice was not against the rules; still such replacement was in principle meant to be an exception, but soon became an established practice. With the notable exception of Antonio Segni (1962–1964), Heads of State have never participated in the daily functioning of the C.S.M., with a sharp decrease in chaired meetings in the last 30 years especially. They do so on extremely relevant or symbolic occasions only.Footnote 21

Features in Table 1 do not reflect the actual influence of the Head of State on the functioning of the C.S.M. though. The Head of State, who is constantly informed about the C.S.M.’s activities and agenda (on which he has a power of assent),Footnote 23 intervenes through other means, such as press releases,Footnote 24 letters addressed to the Vice-president of the C.S.M.,Footnote 25 or more hidden practices such as informal contacts.Footnote 26 He influences the C.S.M. mostly at an informal level through a thick web of agreements aimed at harmonizing conflicting views achieved in the context of confidentiality. In doing so, the Head of State safeguards the proper functioning of the C.S.M. and its relations with other constitutional bodies. He can take an active stance in patrolling the respective institutional boundaries, warning about trespassing.Footnote 27 This is crucial, especially in a context of polarization (with strong conflicts setting the judiciary and sectors of the political elite against each other) that characterized the Italian political landscape from the mid-1980s onward.

Table 1. Number of C.S.M. meetings chaired by the Head of State (1959-2022)Footnote 22

Tellingly, the relevance of the informal dimension on the smooth functioning of the system was explicitly acknowledged by the Constitutional Court in 2013.Footnote 28 The Court had to rule on a competence dispute (“conflitto di attribuzione”) between the Head of State and the Prosecutor’s office of the Palermo court in relation to investigation activities where the Head of State ended up being indirectly and occasionally wiretapped. For the Court, to carry out his tasks the Head of State must be granted “the broadest freedom of action and confidentiality” because some of his activities “do not have a formalized character.”Footnote 29

It is therefore necessary that the Head of State

besides his formal powers, expressed through specific acts explicitly envisaged by the Constitution, carefully relies on what has been defined “persuasive power,” essentially consisting in informal activities that can precede or follow the adoption of specific measures by him or by other constitutional bodies – both for assessing preventively their institutional appropriateness and for testing subsequently their impact on the system of relations between the State powers. Informal activities are therefore inextricably linked to formal ones.Footnote 30

Interestingly, in an obiter dictum the Court extends the relevance of informality to all constitutional bodies, which the C.S.M. is, in performing their functions.

The exceptional involvement of the Head of State in C.S.M. activities and this second layer of informality through which the Head of State exercises his influence avoid the risks of direct involvement in the daily functioning of the C.S.M., which might obscure his role as a safeguard of the proper functioning of the institution, and shields the judiciary from contingent struggles.Footnote 31 Nevertheless, between 1985 and 1992 the Head of State directly and harshly confronted the C.S.M. and its Vice-president.Footnote 32 One could see the many episodes during that seven-year period as a violation of the informal rule requiring the Head of State to be active but rather “invisible,” in order to avoid strains on the judiciary. In turn, the further “moving away” of the Head of State from the C.S.M. in the following years (which again, does not reflect his actual involvement which is still significant) can be seen as a reaction to the violation referred to.Footnote 33

2. The Impartial Chairmanship of the Vice-President

As a substitute for the Head of State, the Vice-president of the C.S.M.—who is elected by the C.S.M. from among its lay members selected by Parliament—convenes and chairs the plenary meetings of the C.S.M., has the power to enact decisions delegated by the President, and is endowed with soft powers of coordination, stimulus, check, and persuasion regarding the collegiate body. According to formal rules, his role is strictly connected to the safeguard of the institutional balance within the C.S.M.Footnote 34 At the time it was envisaged, this was considered an optimal solution, given the conditions. Indeed, it was not regarded as a good idea to endow either the Ministry of Justice or the head of the Supreme Court with the role of Vice-president. Yet, it placed the elected Vice-president in a delicate position.

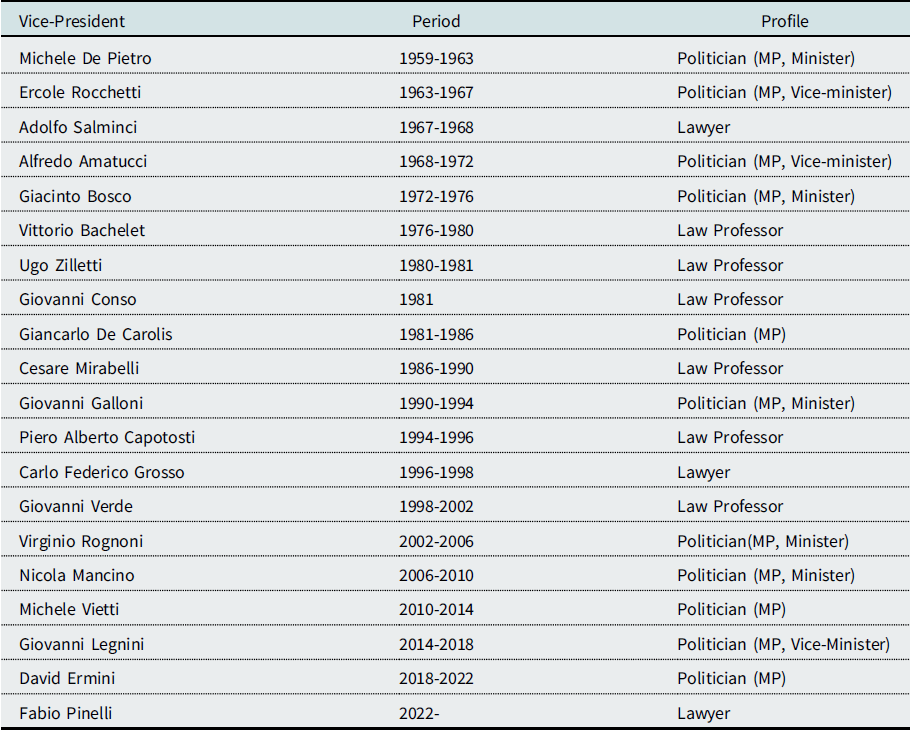

The Vice-president’s impartial role is reflected in the formal rule providing that election is by secret ballot.Footnote 35 Otherwise, it stems largely from informal institutions. For instance, it is a practice that the Head of State does not cast his vote in the election of the Vice-president, even though this happened in 1986, determining the outcome of the election. This generated huge controversy and remained an exception to the established practice. It is also an informal practice not to have official nominees, because any laico can in principle be elected to this position. But, to have a structured election process, there are informal talks on unofficial “candidates” and normally—as is explained infra—unofficial candidates (or the official candidate) happen to be identified at an earlier stage, when the Parliament elects the laici.

Furthermore, the practice is well established of not holding any debates among C.S.M.’s members about the Vice-president election. The idea is that they should not bring with them or implement a “political” agenda: The Vice-president is rather a safeguard of the internal equilibria within the C.S.M. Nevertheless, the Internal Rules of the C.S.M. are silent in this regard and do not explicitly forbid a debate. The resilience of this informal institution is testified to by the attempts made every now and then, yet without success, to introduce such a debate, based on the idea that the Vice-president has an active role to play.Footnote 36

Interestingly, the recently appointed Vice-president of the C.S.M., even though it was expected that he would be elected, stated that he did not prepare any after-election speech because this would not be respectful towards the members of the C.S.M. Also, if a politician, the Vice-president surrenders their party membership when elected.Footnote 37

The Vice-president is elected by a majority of C.S.M. members, yet there is a recognizable trend to identify potential Vice-presidents well before elections take place; at the moment of the selection of the laici by the Parliament. At that point, political parties represented in Parliament by way of informal talks, “identify” the potential Vice-president among the laici they elect. Talks take place not just among the parties but also involve togati, because togati are the majority and thus essential in electing the future Vice-president.Footnote 38 The aim of this practice is to allow the C.S.M. to achieve a consensual election after just one ballot.Footnote 39 This supposedly increases the Vice-president’s impartiality and legitimacy.Footnote 40

In the last 20 years in particular, the position of Vice-president has been fulfilled by fully-fledged politicians, while earlier the profile was that of a legal professional with some political experience. If one looks at Table 2 below, one can detect three periods: An initial one (1959–1976) where there was a practice of electing politically marked Vice-presidents, a second period (1976–2002) where the Vice-president had a more professional profile, and a third period (2002–now) where political profiles come to the fore again (Table 2). In any case, whether a politician or a personality with a more professional profile is elected, whether a consensual or a non-consensual election takes place, the “candidate” has to appear both sufficiently impartial and experienced in political subtleties in order to entertain informal contacts within and outside the judiciary.

Table 2. Profile of C.S.M. Vice-presidents (1959-2022)Footnote 41

3. The Expanding Role of the Steering Committee

In order to fulfil his daily tasks, the Vice-president is assisted by a Steering Committee (Comitato di presidenza). This committee (mentioned only in the law but not in the Constitution) is composed of the Vice-president himself, the President of the Supreme Court, and the Prosecutor general, and enjoys some relevant powers. Some of those powers also broadened through practice. Thus, the Steering Committee decides on the rotating composition of the permanent committees, acts as catalyst for the C.S.M.’s activity, implements C.S.M. decisions, and also manages the budget and appoints members of the C.S.M.’s administrative structure.

The Steering Committee does not exercise these powers alone. Informal communication with all members of the C.S.M. (and the togati especially) takes place in the form of co-decision-making. Nevertheless, in the last 15 years, the Committee has acquired a more assertive role. This new role, allowing it in some instances to counter the dominance of council groups in the decision-making process,Footnote 42 is still controversial and is criticized at times.

One example of such controversies relates to the practice of “agreeing” on the composition of permanent committees or the appointment of the head of the C.S.M.’s Research Department, where togati recently reproached the Vice-president for not holding informal talks in advance in order to achieve a consensual approach. To which the Vice-president bluntly replied: “I do not intend to agree on committees and on the direction of the Research Department with the council group leaders, who no longer exist. This was a practice that I started, but I stopped it. This must be clear to everyone.”Footnote 43

Furthermore, the role of the Steering Committee extends to areas where the relevant responsibility is debatable, such as the external representation of the C.S.M. In 2011, the members of the Steering Committee were summoned to a parliamentary committee hearing during the discussion on the reform of the judicial system. On that occasion the C.S.M. approved a document—drafted by the Vice-president—containing the main lines the Vice-President would follow during his hearing before the parliamentary committee, acting as a representative of the C.S.M.Footnote 44 Still, it cannot be said at present whether or not we are witnessing the development of an established practice.Footnote 45

Another example relates to so-called “interventi a tutela” (themselves an informal practice developed by the C.S.M. since the 1960s and formalized in the Internal Rules in 2009).Footnote 46 These are resolutions to protect individual judges or prosecutors or the judiciary as a whole, if the behavior (declarations, acts, etc.) of judicial or non-judicial actors is detrimental to the prestige and independent exercise of the judicial function. While, according to the Rules, it is the plenary that approves such a resolution, in 2011, during a plenary meeting, the Vice-president delivered a statement labeling a rally organized by a political party outside of a courthouse where an important trial was being held as a threat to judges’ and prosecutors’ independence. While not being technically a resolution of the C.S.M., this statement was meant to replace it due to the lengthiness of the relevant procedure. Seemingly, this practice is becoming increasingly frequent with the tacit and almost unanimous consent of the members of the C.S.M.Footnote 47

To sum up, it appears that established practices involving the Vice-president shape an impartial role that is able to boost the overall legitimacy of the system. This goes together with the Steering Committee’s inclusive approach to decision-making. Nevertheless, recent trends witness the partial erosion of these practices (based mostly on willingness to counter the grip of council groups), even though it is still not possible to talk about their replacement with new practices.

II. Togati and Laici in the Daily Operation of the C.S.M.

After having explored informal practices involving the President, the Vice-president of the C.S.M., and the Steering Committee, I now switch to those involving its elected members who are more directly involved in the C.S.M.’s daily functioning. As mentioned, one-third of them are university professors of law and lawyers with 15 years of practical experience elected by Parliament by a three-fifths majority (laici), and two-thirds are ordinary judges and prosecutors elected from among and by their peers (togati). I will show in particular how informal rules and practices: i) create an “undue” connection between the togati and the judicial associations they are affiliated to, and ii) increase their influence on the C.S.M.’s functioning, furthering the imbalance between the togati and the laici.

1. The Grip of Judicial Associations on the C.S.M.

According to the law,Footnote 48 elected members fulfil their functions independently and impartially. This is an important specification because the election mechanism naturally brings with it the risk of dependence and partiality. Notwithstanding, the set of rules regulating the duties and behavior of the C.S.M.’s elected members is still mostly informal. This issue was indeed targeted only in 2019 by an amendment to the ethical code, while in 2010 the C.S.M. clarified that its elected members should directly and independently deal with any pending issue, and not act as bearers of “the positions of political groups or individual politicians, judicial associations or individual magistrates, due to loyalties or electoral support.”Footnote 49

As regards the togati, this is one of the core issues today,Footnote 50 especially concerning their relation with judicial associations. Such associations, which are also called “correnti,” are groups of magistrates sharing common institutional and broadly speaking ideological views, originally gathered together on the basis, among other things, of their specific understanding of the role of the judiciary in society and of the reform agenda concerning the judiciary. The huge majority of Italian judges are members of a judicial association, and for any judge to be elected as a C.S.M. member, the backing of the relevant judicial association is essential.Footnote 51 This creates a direct link between togati and judicial associations.

In this regard, the practice of establishing “council groups” (gruppi consiliari) within the C.S.M. is notable. These are groupings of togati sharing membership of the same judicial association, similarly to parliamentary parties gathering together senators or deputies belonging to the same party. In that sense, they might be seen as the projection of judicial associations within the C.S.M. Council groups are created informally for coordination purposes at the first meeting of a newly elected C.S.M. For instance, in the current C.S.M. the judicial members belong to four judicial associationsFootnote 52 and thus four council groups were established. These council groups do not enjoy any formal recognition either in the law or in the C.S.M.’s Internal Rules. More importantly, they play a prominent function in structuring the decision-making process. This is done through weekly meetings at which each group establishes (by majority) common stances on given issues to be discussed in the C.S.M.’s committees and the plenary.

The togati are expected to follow their group positions, and the practice of group decision-making is enforced through informal sanctions. In 2012, one togato was expelled from his group after he violated the loyalty duty by voting differently in the C.S.M.’s plenary meeting from the way the group had agreed upon.Footnote 53 On that occasion, the group even officially announced his expulsion during a plenary meeting, notwithstanding the lack of any legal recognition of these entities.Footnote 54 Furthermore, this practice is normally coupled with a practice of inter-group negotiation, where each group’s decision is itself the outcome of vote trading and not just of intra-group discussion.Footnote 55 This can, at times, even result in inconsistent voting in the plenary by members belonging to the same group, as a strategy to limit electoral drawbacks.Footnote 56

All in all, this informal build-up of decision-making through council groups makes it possible for judicial associations to have major influence.Footnote 57 It is indeed normal that a council group and the leadership of the respective judicial association agree on a common stance; thus, the official position of council groups mirrors that of judicial associations.

2. Power Asymmetry Between the Togati and the Laici

The situation is different for lay members. First, with the abovementioned exception of the Vice-president, their professional requirements are interpreted loosely. The practice is therefore to select these members based on party lines where political characterization and proximity prevail over the substance of professional requirements.Footnote 58 Given the three-fifths threshold for election, the majority and opposition parties informally agree on selection of lay members based on the size of parliamentary groups. For some, this results in detrimental outcomes similar to those observed for the judicial members.Footnote 59

To make the election process more open and increase the professional authority of candidates, a recent reform made self-nomination possible. It is thus possible to formally apply as a candidate to be elected as a lay member of the C.S.M., without the need for support by parties or deputies and senators.Footnote 60 Yet, one can easily imagine the weakness of this mechanism, because parties still dominate the process. In any case, the lack of (professional) authority potentially increases lay members’ weakness at different levels. It does not entail dependence on party loyalties alone, but also on knowledge and the expertise gap.

Some have documented a certain degree of acquiescence by the laici to the straightforward stances of the togati.Footnote 61 Their lack of coordination also contributes to this. As one former member put it, lay members are more disorganized

also because – mostly coming from academic ranks – when the possibility for coordination or the need to define at an early stage a line of conduct among the four or five mostly akin members (or less distant ones [. . .]) emerged, precisely four or five different lines of conduct emerged, and coordination ended to be arduous or just impossible.Footnote 62

This generates an important asymmetry allowing the togati to master preliminary activities before decisions are formally taken by the C.S.M. This includes the content of decisions but also the very possibility of a decision being taken on a specific matter, by determining priorities in the working calendar. Priorities in the treatment of dossiers are not always transparent; due to the lack of objective criteria, they respond to elusive rationales and sometimes appear arbitrary.

The weight of council groups has thus been strongly criticized, because they are seen (and probably function) mostly as channels of influence by judicial associations, partly bringing decision-making outside the institution. As a reaction, this sparked attempts at achieving a greater formalization of the decision-making procedure. Among the most debated issues during the reform of the C.S.M.’s Internal Rules in 2016 was the demand for greater transparency of working committees, whose activity happens behind closed doors.Footnote 63

Nevertheless, one cannot deny the positive side of this practice, in that it structures the decision-making process. The C.S.M. is a body endowed with a wide spectrum of competences. Besides the more general ones concerning the judiciary as a whole (opinions on government bills, public statements, etc.), there are more specific ones concerning, for instance, the treatment every year of thousands of individual dossiers concerning just professional assessments, promotions, and appointments. Each of the C.S.M.’s members is supposed to know and decide on each individual dossier. It is easy to understand that C.S.M. members cannot be directly aware of every single dossier and need to rely for the majority of them on other sources of information. This is where the structuring function of council groups comes into play, through an internal division of labor able to detect those most problematic dossiers.Footnote 64 Obviously, this in turn reinforces the asymmetry between laici and togati, because the former are not organized in groups and tend to act through a rather individualistic approach, besides suffering a knowledge gap, as elucidated in the next section.

III. Knowledge Gap and the Informal Influence of the Administrative Technostructure

The C.S.M. operates with the assistance of a wide administrative technostructure supervised by the Steering Committee under the direction of a Secretary-general. The administrative technostructure is composed of the Secretariat and the research department.Footnote 65 This apparatus is relevant both for its characters and for its functions.

On the one hand, until 2022 the Secretariat was formally composed partly of magistrates (magistrati segretari) appointed by the C.S.M., and partly of officials selected by public competition. On the other hand, the practice developed of appointing magistrates for almost all the positions, the relevant legal norms being considered by the C.S.M. to have been tacitly repealed (!).Footnote 66 In 2022, this prompted the legislator to enact new provisions requiring that at least one third of the officials of the Secretariat be recruited from among high-ranking officials from the constitutional bodies or the public administration, and one third of the officials of the Research Department from among university researchers or professors in the legal field or lawyers with ten years of experience.

Furthermore, appointments of magistrati segretari are based on their affiliation to judicial associations and the relative weight of council groups. The magistrates appointed to such administrative positions even participate in the weekly meetings of the relevant council groups, and their appointment is often one of the first steps in a judicial career, as well as in the parallel career within the association they belong to.Footnote 67 Between 2010 and 2014, there was an attempt by the Vice-president to claim a role for the Steering Committee in the selection of this staff, but without success.Footnote 68 Again, following the resilience of these informal institutions, the 2022 reform endowed a committee composed of two top magistrates and three full professors with the task of selecting the staff.

Clearly, the positions of the Secretary-General and, to a lesser extent, of the Head of the Research Department are particularly sensitive. The Secretary-General first used to be appointed through a system that allowed for some influence of council groups, and the legislator recently increased the powers of the Steering Committee. There was no amendment of the rules regarding the Head of the Research Department, who is appointed by the C.S.M. following the proposal of the Vice-President and the opinion of the competent committee,Footnote 69 even though her appointment sparked controversy, with the C.S.M. recently refusing by a large majority to endorse a proposal of the Steering Committee, due to its decision not to negotiate the appointment informally. All in all, (re)formalization of recruitment of the administrative staff is noteworthy, but it is too soon to draw any conclusions.

On the functional side, the administrative technostructure carries out important preliminary activities before any decision-making process can unfold. Just think of the preparation of reports and dossiers by the Research Department, or the role of the Secretariat in drafting the reasoning for decisions relating to appointments of court presidents, transfers, secondments, etc.Footnote 70 According to some accounts, magistrates seconded to the Secretariat and the Research Department play a role that sometimes replaces that of the C.S.M. members (due to a lack of time for proper examination of the dossiers) in articulating the reasoning for resolutions and other decisions. All in all, this creates a situation in which the laici depend on the preliminary activities of non-elected expert magistrates, who in turn are conditioned by togati, and ultimately judicial associations by means of loyalty ties.Footnote 71 One may add that members of the technostructure are employed for a much longer time than C.S.M. members, thus representing the institutional memory of the C.S.M.. This in turn emphasizes the imbalance with the members of the C.S.M. who change every four years.

To conclude, this is a second line of dependence—in terms of “information asymmetry”Footnote 72 —of lay members, favored by the influence of the togati and their council groups. As a former member of the C.S.M. put it bluntly,

All considered, a lay member is, at its beginnings, essentially ‘in the hands’ of the relevant magistrato segretario (each committee has two of them), whom of course he did not select but just found already assigned and who [. . .] usually (yet with some commendable exceptions) actually ‘responds’ to the judicial association who ‘brought’ him in the C.S.M.Footnote 73

C. Governing Judicial Careers: Confronting Informal Practices and the Push Towards Formalization

Having explored how informal institutions shape the C.S.M.’s internal balance and decision-making dynamics in general, I now look more specifically at informal institutions affecting the C.S.M.’s set of powers relating to the careers of judges, namely the appointment of court presidents and professional assessment.

I. Negotiating the Appointment of Court Presidents

The appointment of court presidents in Italy is highly formalized.Footnote 74 The law identifies three criteria: Seniority, merit, and aptitude, which the C.S.M. has detailed in a very baroque manner through quite a number of “general and specific indicators” and so-called “comparative criteria.”Footnote 75 It is commonly acknowledged that this hyper-regulation did not, in practice, curb the C.S.M.’s discretion; quite the contrary. This opened up room for informal institutions whose rationale is not necessarily the one inspiring formal rules.

The so-called “nomine a pacchetto” (“appointment packages”) are a very common example of this. This is a widely documented practiceFootnote 76 that favors agreements among “council groups” to divide among themselves the top positions in courts (or other important positions).Footnote 77 When a vacancy at a court is announced, it is not filled immediately and is postponed until a sufficient number of vacancies can be accumulated in sealed agreements on “appointment package(s).” The plenary of the C.S.M. then votes on the packages altogether, and not for each individual candidate separately. By allowing a single vote to fill a number of positions, this practice favors a system where judicial positions are divided up among the different judicial associations who agreed upon the package (a phenomenon labeled as “lottizzazione”).

This practice clearly depends on the cohesiveness of “council groups” (ensured by their decisions being taken by majority, as referred to in the previous paragraph), because such cohesiveness allows for only occasional inter-group agreements. Yet, even after lengthy negotiations,Footnote 78 decisions are not always unanimous, for instance when two distinct packages are presented by opposing “council group” coalitions.Footnote 79 Agreements may even failFootnote 80 and in some cases prospective agreements can fix this failure at the next “round.”Footnote 81 However the dynamics unfold, it is still up to the judicial members to lead the game. This also entails establishing informal channels of communication with other judges or prosecutors, but also with actors outside the C.S.M., such as politicians, as the “Palamara affair” witnessed to the highest degree.Footnote 82 As a member of the judiciary put it, “lay members [. . .] elected by Parliament act as bit players.”Footnote 83

There are three main negative consequences of this practice. The first relates to the transparency of the relevant decisions. The second, possibly more serious, is the inefficiency deriving from belated appointment to such positions, in some cases for as long as a year or more. Thirdly, because the process is not transparent and the decision-making rationale does not straightforwardly rest on the principles defined by the law (merit and especially aptitude to hold a given position), this generates a pathological malfunction of the legal system. The Supreme Administrative Court (Consiglio di Stato), which has the competence to review C.S.M. decisions (except for disciplinary decisions), indeed often annuls decisions on appointments of court presidents, considering their motivation inadequate.Footnote 84 This in turn increases delays even more and determines institutional strains among two constitutional bodies.

This explains why there have been attempts to counter this practice (and its consequences in particular) by formalizing the process, attempts which followed the Head of State’s official stances against the practice. In 2014, time limits were introduced for appointment to top positions, and the replacement of the rapporteur in charge of the dossier was envisaged in the event of non-compliance. In 2016, the Internal Rules of the C.S.M. established that appointment packages relating to the same court could not be voted all together, imposing a separate voting process for each candidate, and allowed for alternative candidates being proposed during plenary debate.Footnote 85 The same regulation also allowed for greater transparency of the meetings of the competent committee.Footnote 86 Finally, the reform of judicial organization approved in 2022 introduced quite a few innovations, forbidding “appointment packages” in principle, imposing duties of greater openness and transparency, setting stricter provisions as to the criteria to be followed and the sources of information.Footnote 87 This indicates a strong trend towards formalization that can be detected also in relation to other areas of judicial governance following the Head of State’s official stances.

II. Upwardly Leveled Professional Assessment

A similar push towards formalization can also be observed in relation to professional assessment. Indeed, the Italian judicial assessment system is highly formalized and, on paper, very effective—possibly one of the strictest among EU countries.Footnote 88 In fact, after a reform in 2006, every judge (and prosecutor) undergoes professional assessment every four years, while before 2006 there were four assessment rounds in the whole of a magistrate’s career.Footnote 89 The C.S.M. is the authority formally assessing the judge, but it does so relying on an individual report by the head of that judge’s court complemented by an opinion of the local judicial council (consiglio giudiziario). The proposal is drafted taking into account the parameters and the relevant indicators established by the C.S.M.Footnote 90 and relying on different sources of information.Footnote 91

The system is not considered to be effective in its functioning for multiple reasons. First, assessment is positive in the great majority of cases. This did not change after the 2006 reform. It is reported that between 1979 and 2007, negative assessment varied between 0.4 percent and 0.9 percent concerning usually magistrates who were awarded disciplinary sanctions or were awaiting criminal proceedings. Similar features appear with reference to the following period, with “positive” assessment in 98.22 percent (also faced by magistrates under disciplinary sanctions or serious work delays),Footnote 92 “non-positive” assessment in 1.14 percent of the cases, and “negative” assessment in 0.65 percent of cases.Footnote 93

These features are the result of informal practices involving court presidents and local judicial councils, both tending to be highly encomiastic in assessing judges within their respective competences. This can probably be explained by personal relationships, making it difficult to officially provide negative opinions about colleagues, and/or again as a consequence of judicial associations’ corporatist attitudes in local judicial councils. For instance, it is not common practice for local judicial councils to rely on a diversified set of sources of information to draft their opinions, taking into account lawyers’ complaints. Exceptions could be noted though, with some local judicial councils being more willing to involve lawyers.Footnote 94

An additional problem is that assessment strongly emphasizes merits, but the aptitude to hold a specific position less so, as it does not allow to differentiate among magistrates who received positive assessment.Footnote 95 The lack of articulation in assessment allows for the C.S.M. to have greater discretion when deciding on appointments to specific positions.Footnote 96 A high degree of discretion, which naturally entails conflicting views, might not be a problem; quite the contrary, because discretion is inherent in a constitutional body of a collegiate nature.Footnote 97 The problem rather lies in the parameters funneling discretion: While clear and understandable on paper, they change nature in practice, leaving a wide margin (actually and even more so in the public’s perception) for personal loyalties and group allegiances.

A third problem is the overlap with disciplinary accountability.Footnote 98 Due to the upwardly leveled professional assessment, the disciplinary system tends from a functional perspective to replace professional assessment, which entails both its distortion (because the disciplinary body deals with inefficiencies that should not incur disciplinary sanctions in principle) and an increased number of procedures.Footnote 99 All in all, this set of negative effects of informal institutions in the area of professional assessment pushed the legislator into introducing stricter regulation.Footnote 100

III. Resisting the Weight of Informal Loyalties and the Push Towards Formalization

What comes to surface is the considerable influence of council groups (as a projection of judicial associations within the C.S.M.) in deciding on appointments of court presidents through intense, and at times lengthy, negotiation. Furthermore, I stressed the trivialization of one fundamental tool for judicial accountability, such as professional assessment, as a consequence of informal relations taking place at different levels: Courts, with the deference of court presidents towards judges they are supposed to assess, local judicial councils, and the C.S.M.

To complete this picture, one should stress that, strong influences in these two crucial areas of magistrates’ careers notwithstanding, an opposite trend exists, countering the weight of corporatism and informal distortions. The adoption of new formal rules in 2022 in the areas of the judicial appointment of court presidents and of professional assessment are actually a direct consequence of this.

As to appointments, one should mention the increasingly recurring and inflexible statements of the Head of State in relation to the grip of judicial associations on the C.S.M.’s decisions, especially those relating to court presidents.Footnote 101 Tangible attempts to oppose such informal practices in both areas have been made by the Vice-President and the Steering Committee. Their opposition to positive assessment succeeded when they approached the issue proactively,Footnote 102 otherwise, corporatist attitudes prevailed, also entailing uneven and inconsistent assessments over time. All in all, this contributed to the sparking of public debate, making these practices increasingly costly and preparing the ground for and legitimizing legislators’ interventions.

To conclude, informal institutions in these two areas of judicial governance paint a grim picture of what happens behind the scenes of formal rules, yet this picture is more nuanced and dynamic than one might expect. In this sense, we have witnessed new practices coming into existence in recent years, which pushed for formalization aimed at neutralizing those informal practices that are widely considered strongly negative.

D. Conclusion: The Pervasiveness of Informal Institutions in the System of Judicial Governance

This article has dealt with a set of informal institutions in judicial governance. It has provided details of how these institutions work and shed light on the actors shaping or opposing them, exploring what the consequences thereof are. The analysis displays a landscape of interactions concretizing such practices. Some of these are hidden, some are not. Some take place among judicial actors, some originate among judicial and non-judicial actors, and some among non-judicial actors only. Some are based on patronage, some on personal loyalties, some are more ideological in character. Yet, they all in one way or another affect judicial governance.Footnote 103

The Italian case-study proves how pervasive informal institutions are in judicial governance and gives evidence of the scope of their operation. These concern the Head of State acting as C.S.M. President, the C.S.M. Vice-president and the Steering Committee, judicial and lay members, the administrative apparatus, actors formally outside the system of judicial governance (political parties, individual politicians, or judicial associations), court presidents in their relationship with “their” judges, and local judicial councils. No one escapes informality. This confirms what has been suggested so far about the importance of informal institutions in established democracies, and not just “where formal institutions are new, underdeveloped, or dysfunctional.”Footnote 104

It is useful to briefly restate the informal rules and practices detected, emphasizing the factors behind the relevant patterns, their origin, the functions played by informal judicial institutions, and the positive or negative assessment of informality.

As regards the Head of State, informal institutions relate to his quantitatively limited participation in meetings coupled with the use of alternative channels of influence based on confidentiality and self-restraint. These informal institutions—whose origin Footnote 105 cannot be precisely stated but is rather a process—are essential for the President of the C.S.M. to fully play his role of safeguarding a delicate system of checks and balances within (balances between its multiple components) and outside the C.S.M. (respect for institutional boundaries between the C.S.M., State powers, and other constitutional authorities). Also, it serves—as far as possible—to shield the judiciary from controversies. There have been specific interruptions to some of these informal institutions, but they have proved resilient. The subsequent reaction has made them even more robust.

As for the Vice-president and his appearance of impartiality, I have referred to practices related to the election process, complementing the few formal provisions on a secret ballot set in the C.S.M.’s Internal Rules. Interestingly, informal institutions extend beyond the very moment of the Vice-President’s election, to involve also actors formally outside the system. This is the case for political parties informally choosing, while electing lay members, and through talks with judicial members of the C.S.M., the would-be Vice-president. In general, his impartial appearance does not seem to be challenged by the prevailing political profile of the Vice-presidents elected over the years—a profile that responds to a need for “political wisdom.” Then, impartiality and consensus spill over in the exercise of the functions that the Vice-president is assigned to by formal rules through resorting to shared decision-making. However, I reported a breach of this practice—the Vice-President refusing to involve the C.S.M.’s members in some important decisions—to be understood within the context of an expanding role for the Vice-President and the Steering Committee to counter the grip of council groups. Whether we are witnessing a shift from one informal practice to another it is still too soon to say.

In general, institutional choices relating to the chairmanship appear wise, with the relevant informal practices largely contributing to the functionality of the system. This might have partly neutralized those conflicts and excessive imbalances experienced in systems where different arrangements have been devised, bestowing the steering function on personalities directly involved in confrontational dynamics.Footnote 106

As regards the togati and laici informal institutions are more straightforward and directly compete with formal rules. For the togati, the practice of establishing council groups challenges the provisions on independence and impartiality. Yet this practice—that is rather weakly countered and appears to be very resilient—not only has a loyalty rationale but can also be explained by typically organizational needs (structuring decision-making). The same goes for the laici, whose relevant informal institutions challenge their legal framing as independent and impartial. I mentioned the loose interpretation of their professional requirements which entails both politicization and a lack of authority, letting them at the margins of the C.S.M.’s decision-making. This brings us to clear asymmetries. Exceptions usually concern the Vice-president and those elected members coming from academia.

Informal institutions relating to the administrative technostructure are multiple, all of them in the direction of strengthening the corporatist tendencies of the C.S.M.’s decision-making. Again, counter-trends emerge, both informal (related to the attempt by the Steering Committee to assert its own role) and formal (by incremental attempts to eliminate these practices through legislation). Despite the scarce attention paid to it, the salience of this dimension is due to the practice of the C.S.M.’s (lay) members of just relying on the dossiers prepared by these magistrates, without “fighting back” (while the opposite has actually happened).

The hold of council groups on decision-making reflects to the highest degree in the appointment of court presidents through “appointment packages” resulting from lengthy negotiations taking place within and outside the institutional walls of the C.S.M. This has fundamentally negative consequences in terms of efficiency, the functionality of the legal system, and transparency. This possibly affects citizens’ trust overall but may affect even magistrates’ trust of their court presidents. Judicial corporatism is a problem that starts to hurt the judiciary too. The outcome of a referendum organized by the Associazione Nazionale Magistrati among its members on the introduction of the selection by drawing lots of their “representatives” within the C.S.M.Footnote 107 and a survey of the European Network of Councils for the Judiciary on magistrates’ perceptions of the correctness of appointments of court presidents are telling. Here, too, trends towards formalization are strong, notwithstanding the resistance of judicial associations’ leaderships. Similar considerations hold for professional assessment, even though in this area it might prove more difficult to escape the weight of informal practices.

Taking the described phenomena together, two types of factors behind the relevant patterns stand out. First, informal institutions come to the surface due to legal factors, i.e., the flexibility of the legal framework, which may or may not be desired. Flexibility can be desired, for example when the legal framework is intentionally open to multiple developments, as in the case of practices relating to the position and powers of the Head of State and its relation to the Vice-president and the C.S.M. at large, or the powers of the Steering Committee defined in the C.S.M.’s Internal Rules. Flexibility is undesirable when the legal framework is too complex or has loopholes, allowing for informal practices that do not necessarily fit with the legal rationale. This is the case with the hyper-regulation of the criteria for appointing court presidents (complexity), or the lack of regulation of council groups, e.g., their prohibition or the ban on members of the technostructure participating in council groups’ activities (loopholes). The second type of factor pertains to the weight of extra-legal (f)actors distorting the legal setting through informal practices. This is the case with judicial associations, which affect the operation and organization of the C.S.M. to a higher degree (as in the case of the council groups, or in appointments to the administrative technostructure) or its judicial governance functions (agreements for appointments of court presidents, professional assessment). Also, the weight of political parties is quite obvious in the informal institutions relating to the election of non-judicial members of the C.S.M.

To conclude on the positive or negative assessment of informal institutions as to their effect on core judicial values and the quality of democracy, the impact seems clear-cut on accountability, transparency, efficiency and trust, yet there is no straightforward general answer on the direction of such impact, which is both positive and negative on a case-by-case basis. For sure, informal institutions should not be seen only as negatives. This is not just because some informal institutions are positive, while others are negative. There are also cases where the same informal institution has negative and positive effects at the same time. One example from the pool of those mentioned is the sharing by the Steering Committee of its decision-making powers with the members of the C.S.M.: This is a positive practice, because it avoids tensions that can affect the Vice-president, but at the same time it further increases the grip of the togati on the actual functioning of the C.S.M.

Overall, the formal template of judicial governance based on a delicate balance of accountability looks in practice to be stretched very far, in general and especially when it comes to the appointment of court presidents (but for other dimensions of judicial governance this might not be necessarily true).Footnote 108 This is still the case notwithstanding the counterweight of other actors within and outside the C.S.M. As observed elsewhere, over time this model has contributed to securing the independence of the judiciary in a post-authoritarian setting, but the picture is less satisfactory in terms of judicial accountability’s efficiency, transparency, and trust. It is possibly still tenable in terms of legitimacy, thanks to the moderating role of the Head of State and the pressures inducing changes in judicial culture and ethics. As someone put it, prefiguring future developments,

Something has changed. There is a different dynamic, in the functioning of the C.S.M., compared to what was imagined by the drafters of the Constitution. And at this point the composition of the C.S.M. should be reconsidered. Also because the decision to have a majority of togati was the result of a resolution of the Constituent Assembly passed by a whisker.Footnote 109

Whether such a far-reaching change will happen or not may depend on how informal institutions will develop in the future.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges David Kosař, Katarína Šipulová, and other members of the Judicial Studies Institute at Masaryk University for the invaluable comments and feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

Competing Interests

The author declares none.

Funding Statement

The research leading to this article has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (INFINITY, grant number 101002660).