A. Introduction

Regulation 1367/2006, mostly known as “the Aarhus Regulation” (hereinafter “AR”), is the legislative measure adopted in 2006 by which the EU has bounded its institutions and bodies to the obligations stemming from the Aarhus Convention.Footnote 1 The Aarhus Convention is a UN international agreement enshrining three key procedural rights with a strong environmental component, namely the right to environmental information, the right to participate in the environmental decision-making, and the right to access to justice in environmental matters.Footnote 2 The AR was amended in October 2021,Footnote 3 after a long legal mobilization process, which has also seen the Aarhus Convention Compliance Committee (hereinafter “the ACCC”) playing a crucial role in advancing the pleas of the European environmental movement.Footnote 4

One of the key features of the AR, is that this provides—under Article 10—for an internal review mechanism allowing “members of the public” broadly defined—today not only environmental organizations but also individuals—to submit a written request aiming to obtain the internal review of an EU administrative act contravening EU environmental law. This request must be addressed directly to the institution or administrative body of the Union which adopted the contested act. In case the complainant is not satisfied with the answer obtained by the EU institution or administrative body, it can challenge the answer received directly before the EU judiciary, as laid down under Article 12 of the AR. As will be illustrated in the present contribution, the Aarhus mechanism of internal review has been deeply affected by the reform which occurred in the 2021 reform that changed the legal opportunity structures (LOS) available to civil society organizations in the environmental context.

The “new” AR–that is the post-reform version of the AR–can be considered as the preeminent advancement obtained by environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs) as a result of their legal mobilization activities aiming at contesting the legality of EU law.Footnote 5 The present contribution will show that ENGOs, far from basking in the glory of their achievement, have already set to work “testing” the new AR, in order to explore its potential for present and future legal mobilization. In the frame of this Article, I intend to focus on the use of the AR in the energy and climate context, representing the second most mobilized EU policy domain under the new AR, the first one being “pesticides,” and the one where the European Commission has provided most responses so far. In this regard, I decided to concentrate my analysis only on the requests presented to the European Commission, because this is by far the institution receiving most requests for internal review.Footnote 6 In terms of methodology, I carried out traditional doctrinal as well as qualitative analysis of the requests submitted since October 2021 to the European Commission, and of the answers provided by the latter to the complainants. This pretty vast material is publicly available online on the European Commission repository of the internal review requests submitted under Article 10 of the AR.Footnote 7

In terms of structure, in the first section I will set out the main novelties introduced in October 2021 in the AR and emphasize what these changes entail for legal mobilization in the EU. Then, I will provide an empirical overview and critical analysis of how the new AR has been mobilized so far by environmental organizations in the energy and climate context. In particular, I will focus on two case studies: One brought against the EU regulatory framework governing the National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs), and another one concerning a delegated act adopted pursuant to the Taxonomy Regulation.Footnote 8 Because the requests indirectly targeting the NECPs and the Taxonomy Regulation constitute the vast majority of the requests submitted under the internal review mechanism in the areas of energy and climate. Furthermore, the files respectively, and indirectly, concerning the NECPs and the Taxonomy Regulation present deep similarities with the requests submitted in the same sub-category, in other words those brought against the same EU administrative act. Such similarities reveal themselves in terms of arguments presented by both sides, namely the ENGOs in their requests and the European Commission in its responses. This justifies an analysis based only on two case studies, out of nineteen requests presented in the energy and climate context.

Then, the empirical overview of each request will be followed by preliminary conclusions embedding the critical appraisal. The final section will set out the overall conclusions of the Article.

The Article holds that the internal review mechanism is being used strategically by ENGOs, with the aim to trigger “systemic” legal mobilization against EU environmental and climate change law. This by indirectly challenging wider EU policy measures constituting the foundations of EU climate policy, such as the Governance Regulation and the Taxonomy Regulation, vis-à-vis the general principles of EU environmental law and the EUCFR.

In addition, the present contribution holds that the reform of the AR has turned the internal review mechanism from an “administrative” into a “scientific” dispute settlement system, through which ENGOs and EU institutions can compare scientific evidence and disagree about the way this has been taken into account in the EU policymaking. In other words, I argue that the AR reform has provided more transparency on the science underlying EU environmental law and policy, by forcing the EU institutions, and mostly the European Commission, to explain more accurately how science was used as a basis in the EU policymaking concerning the environment and climate change.

Moreover, this Article maintains that increased transparency over the use of scientific evidence in the EU policymaking is not an ENGOs’ goal per se, as these ultimately aim to achieve a much more substantive result, that is the contestation of the legality of EU law. Environmental organizations thus consider the submission of requests for internal review a necessary preliminary step in order to be granted standing at a later stage, before the General Court of the EU (GC) and then—eventually—before the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU), under Article 263(4) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). This is confirmed by the number of cases, eighteen, currently pending before the EU judiciary.Footnote 9 Such pending cases entail that the submission of a request for internal review under the AR is a preparatory − administrative − step that environmental organizations usually take in view of triggering litigation, depending on the answer received by the EU institution concerned. Put in these terms, “strategic” is not only the subsequent litigation before the EU Courts, but also the preliminary submission for internal review. For this reason, such administrative submissions represent a form of legal mobilization capable of explaining in more accurate terms how strategic litigation is deployed by environmental organizations in the EU in both, procedural and substantive terms. Finally, this Article argues that legal mobilization under the “new” AR shows, even more clearly than before the reform, how specific EU procedures “shape” the actors being empowered by strategic litigation. In this case, the ENGOs empowered by the AR are the ones possessing a high level of technical sophistication, which allows them to effectively act as scientific interlocutors of the EU institutions on behalf of the wider public.

B. The New Aarhus Regulation

In the present section, I will examine the main amendments introduced in the AR, which – as mentioned above - have entered into force since October 2021.Footnote 10 These amendments are crucial to provide a preliminary assessment of the new legal opportunities available under EU law, as will be further discussed in the present contribution. The amendments reported here mainly refer to (i) the new definition of “administrative act” laid down under Article 2(1)(g) AR; (ii) the possibility for “other” members of the public to submit a request for internal review; and (iii) the broader timeframe acknowledged to complainants and EU administrative bodies dealing with requests for internal review.

I. The New Definition of “Administrative Act”

This paragraph compares the old and new definitions of “Administrative Act” laid out under Article 2(1)(g) of the AR. The old version defines “Administrative Act” as “any measure of individual scope under environmental law, taken by a Community institution or body, and having legally binding and external effects.”Footnote 11 The new version defines “Administrative Act” as any non-legislative act adopted by a Union institution or body, which has legal and external effects and contains provisions that may contravene environmental law within the meaning of point (f) of Article 2(1).”Footnote 12

In light of the new definition, the “administrative acts” which can now be contested through the internal review procedure established under the AR, are “regulatory acts,” namely non-legislative acts of general application. Non-legislative acts are all those acts which are adopted without following the legislative procedures described in the EU Treaties.Footnote 13 This amendment is significantly influencing ENGOs’ strategic litigation options, as will be discussed later in this Article.

Furthermore, under the “old” version of the AR, “administrative acts” were non-legislative acts adopted “under” environmental law, which seemed to imply, as stressed by the ACCC in its findings,Footnote 14 as “having Article 191 TFEU as a legal basis.”Footnote 15 On the contrary, the new definition specifies that the administrative acts and omissions covered by the internal review mechanism are those that contravene provisions of environmental law, regardless of their legal basis. Another important novelty for the environmental movement, which is expected to broaden legal mobilization against EU regulatory acts having an effect on the environment.

Even the word “binding” has been removed from the definition of administrative act, which now are required “only” to produce “legal and external effects.” As a result, even acts that formally would not have any “binding character” could still de facto be able to produce legal effects and “bind” third parties.Footnote 16 The removal of the word “binding” should thus encourage the adoption of a more substantive hermeneutic approach, in other words, based on the content rather than the pure form of the act, by the EU judiciary.Footnote 17

Another key aspect which is worth stressing is the lack of any reference to the presence of implementing measures. Indeed, even the current text of Article 2(1)(g) AR does not make any reference to implementing measures, suggesting that even regulatory acts entailing implementing measures, at national or EU level, can be subject to an internal review by the competent EU administrative body or institution. In this regard, it is worth reminding that the original proposal presented by the European Commission explicitly excluded from the scope of the internal review those provisions of an administrative act “for which Union law explicitly requires implementing measures at Union or national level.”Footnote 18 This point was heavily contested by ENGOs,Footnote 19 which knew that this amendment would have further constrained their legal opportunities under EU law, so they strongly advocated during the decision-making process and succeeded in having that specific part of the proposal removed from the text of the Regulation.Footnote 20 This point is significant from a legal mobilization perspective, as it shows how leading European environmental organizations, like ClientEarth, EEB and CAN Europe, keep “shaping” the legal opportunities available under EU law by not settling for litigation, but by rather combining the latter with other advocacy tools, in order to make their overall mobilization tactic more effective.Footnote 21

The final outcome is that the internal review mechanism under the AR can now be sought for regulatory acts entailing, or not entailing, implementing measures and contravening provisions of environmental law. On the contrary, regulatory acts contravening provisions other than environmental law can be challenged only under Article 263(4) TFEU and only if such acts do not entail implementing measures.Footnote 22 In the next section, I will now outline the other main procedural novelties introduced in the AR.

II. Procedural Amendments In The New Aarhus Regulation

Crucial novelties have also been introduced in relation to the subjects who can present a request for internal review to the relevant EU administrative bodies. Indeed, under the new Article 11(a) a request for internal review can now be presented not only by ENGOs, but also by “other” members of the public, subject to certain conditions.Footnote 23 Individuals can now submit a request by showing the impairment of a right caused by the alleged contravention of EU environmental law by the relevant EU administrative body and that they are directly affected by such contravention in comparison to the public at large.Footnote 24 Moreover, even a group of individuals demonstrating “sufficient public interest” can now submit a request for internal review, which must be supported by at least 4,000 members of the public residing or established in at least five Member States (MSs), with at least 250 members of the public coming from each of those MSs.Footnote 25 However, in both scenarios, the members of the public shall be represented by an NGO or by a lawyer authorized to practice before a court of a MS.Footnote 26 The new AR further requires that that NGO or lawyer “shall cooperate with the Union institution or body concerned” in order to establish that the quantitative conditions mentioned above are met, where applicable, and shall provide further evidence thereof upon request.Footnote 27

Finally, the new text of the AR also presents a different timeframe for submitting requests for internal review under Article 10, which has now been extended from six to eight weeks, same in case of an alleged omission.Footnote 28 More time is also for EU administrative bodies to give their answer, namely from the “old” twelve to the new “sixteen” weeks after the expiry of the aforementioned eight weeks deadline, and in no case beyond twenty-two weeks from that same deadline.Footnote 31 In this regard, the new timeframe(s) should favor both, ENGOs seeking the internal review of EU administrative acts, as well as EU administrative authorities called upon to respond.

Having outlined the main novelties introduced in the AR, I will now provide the reader with an empirical overview of how the new AR has been mobilized in the energy and climate context by environmental organizations since its reform.

C. Legal Mobilization Under the New Aarhus Regulation

Just a few months after the 2021 revision, ENGOs immediately started to submit requests for internal review to the relevant EU institutions, agencies and bodies. In fifteen years under the old AR, the Commission received forty-eight requests for internal review. In less than three years under the new Regulation, the Commission has already received forty-three requests.Footnote 32 Below, Table 1 provides a general overview of the environmental policy areas mobilized by ENGOs under the new AR from the reform to the 7th of March 2024. As mentioned in the introduction, this data stems from a qualitative analysis of the requests submitted since the 2021 reform and published on the European Commission Aarhus repository available online.Footnote 33 As the reader can easily notice, thirty-nine out of the forty-three requests—90.7%—submitted to the European Commission, either concern pesticides or energy and climate.

Table 1. Environmental policy areas mobilised by ENGOs under the new ARFootnote 29

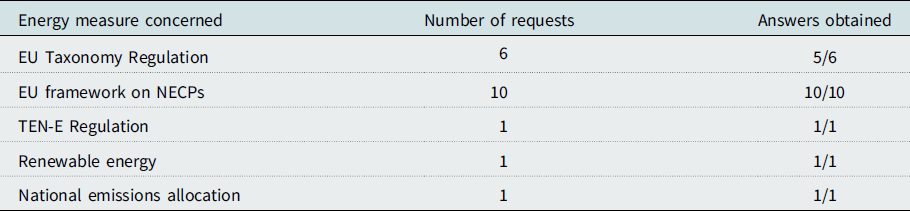

Conversely, Table 2 unpacks the main topic of the Article, namely the requests submitted in the areas of energy and climate. This is shown by providing a deeper overview of the specific type of internal review requests.

Table 2. Requests for internal review under the new AR in the area of energy and climateFootnote 30

Having provided an overview of the requests submitted under the new AR, in the next section I will first analyze the requests indirectly concerning the NECPs; then those indirectly concerning the EU Taxonomy Regulation. The analysis included in each section will be followed by preliminary conclusions.

D. National Energy and Climate Plans

With regard to the NECPs, these were introduced by Regulation 2018/1999, Governance Regulation, on the governance of the energy union and climate action,Footnote 34 and require each EU MS to establish a ten-year integrated energy and climate plan to contribute to the achievement of the EU’s energy and climate targets for 2030.Footnote 35

Interestingly, all the requests concerning NECPs were based on the same grounds of review. In essence, all ENGOs referred to the ACCC findings in Communication ACCC/C/2010/54 on compliance of the EU regulatory framework on National Renewable Energy Action Plans (NREAPs) with Article 7 of the Convention, providing rules on public participation concerning plans, programs and policies relating to the environment.Footnote 36 Indeed, in 2012 the Aarhus Committee found that the EU did not guarantee sufficient, fair and transparent public participation in relation to the adoption of the NREAPs, setting out national targets for the share of energy from renewable sources consumed in transport, electricity and heating and cooling by 2020.Footnote 37 Following these findings, in 2014, the Meeting of the Parties (MOP) adopted Decision V/9g, requiring the EU to: (i) “[A]dopt a proper EU regulatory framework and/or clear instructions” that would ensure that member States put in place arrangements with respect to the adoption of NREAPs, or the plans that take their place, that would meet each of the elements of article 7;Footnote 38 (ii) “ensure that the arrangements for public participation in its member States are transparent and fair and that within those arrangements the necessary information is provided to the public”; and (iii):Footnote 39

[E]nsure that the requirements of article 6, paragraphs 3, 4 and 8, of the Convention are met, including reasonable time frames, allowing sufficient time for informing the public and for the public to prepare and participate effectively, allowing for early public participation when all options are open, and ensuring that due account is taken of the outcome of the public participation [and] [. . .] adapt the manner in which it evaluates NREAPs accordingly.Footnote 40

However, further investigations undertaken by the ACCC between 2017 and 2021 on the EU’s failure to comply with Decision V/9g revealed that even the EU regulatory framework on NECPs presented the same shortcomings ascertained in relation to the EU framework on NREAPs. The new violation of Article 7 of the Convention, was formalized in 2021 by the MOP in Decision VII/8f.Footnote 41

This led ENGOs to argue −under the new AR− that the EU’s failure to comply with Decisions V/9g and VII/8f constituted an “administrative omission,” for the purposes of Article 2(1)(h) AR as amendedFootnote 42 breaching the obligation to review the relevant EU regulatory framework that the MOP decisions had imposed. Article 2(1)(h) AR defines “administrative omission” as “any failure of a Union institution or body to adopt a non-legislative act which has legal and external effects, where such failure may contravene environmental law within the meaning of point (f) of Article 2(1).”Footnote 43

In this regard, the Commission rejected all ten requests for internal review concerning NECPs. The Commission mainly held that NECPs are plans adopted at national level by domestic authorities, not by the EU institutions or bodies.Footnote 44 The Commission also maintained that the EU has actually adopted a general legislative framework for public participation at national level in the process leading to the adoption of NECPs.Footnote 45 Moreover, the EU executive contested its alleged failure to comply with Decisions V/9g and VII/8f and stressed that under Recital 11 of the AR, an “administrative omission” should be “covered where there is an obligation to adopt an administrative act under environmental law.”Footnote 46 On this point, the Commission noted that:

[I]n the case at hand, the elements that would show the existence of an administrative omission within the meaning of the provision recalled above are not set out in your requests. In particular, your requests for review identify the alleged ‘administrative omission’ only in a general manner as ‘not implementing the recommendations set out in Decision VII/8f.’ By so doing, you fail to identify what, if any, administrative act the Commission should have adopted.Footnote 47

In light of this, all requests were deemed inadmissible but none of these decisions of rejection was actually challenged before the EU judiciary under Article 263(4) TFEU. Despite the lack of litigation before the CJEU, these requests for internal review are still pertinent in the present discussion to show how ENGOs are using the new AR to mobilize not only the way the individual NECPs have been adopted at domestic level, but also the EU Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action. In this regard, in the next section I will now set out my preliminary conclusions on ENGOs requests targeting NECPs under the new AR.

E. Preliminary Conclusions

Through the requests concerning the EU regime on NECPs, ENGOs tested the potential of the new AR for climate mobilization based on breaches of participatory rights. Indeed, all the ten requests received by the EU executive on NECPs were based on an alleged incompatibility between the relevant EU regulatory framework, embedded in the Governance Regulation, and Article 7 of the Aarhus Convention which lays down rules on public participation concerning plans, programs and policies relating to the environment. In other words, ENGOs—by using the ACCC findings in support of their arguments—claimed that they had not been given adequate room to participate in the adoption of NECPs at the national level due to flaws embedded in the EU regulatory framework. As mentioned above, all ENGOs’ requests were deemed inadmissible by the European Commission, but no organization decided to contest such denials before the EU judiciary.

The answers of the European Commission and the lack of litigation contesting such answers show how inadequate the internal review mechanism is for challenging the NECPs. Indeed, these are domestic plans adopted at national level, whose procedural flaws can hardly be challenged directly before the European Commission. However, as mentioned here above, ENGOs stressed that they were not contesting legal flaws embedded in the procedure leading to the adoption of NECPs per se, but they were actually contesting the whole EU regulatory framework governing the adoption of NECPs, namely the Governance Regulation. Nevertheless, being this regulatory framework established under a legislative measure—which is therefore excluded from the scope of the AR—this could not be directly contested through the Aarhus internal review mechanism. What kind of remedies can thus be deployed to contest NECPs?Footnote 48 I would argue that ENGOs should primarily trigger litigation against such plans directly at national level, before the competent domestic jurisdictions. In this regard, I maintain that—in most EU countries—the most adequate judicial forum for contesting this type of plan is constituted by administrative courts. First, the nature of such contested measures is the one of a national plan, adopted by public authorities in the exercise of public powers, whose scrutiny is usually reserved to the jurisdiction of administrative courts. Second, administrative judges are the best equipped to (i) check whether administrative procedures have been followed in accordance with the law; and (ii) assess the margin of maneuver deployed by public authorities in the exercise of public powers.

Furthermore, triggering litigation at national level would not exclude the possibility of indirectly contesting the validity of the Governance Regulation as well. Indeed, the parties involved in judicial proceedings triggered against a NECP would be in the position to ask the judge to refer questions concerning the validity of the Governance Regulation directly to the CJEU. The real issue I see in this scenario would actually be to convince the CJEU to rely on the Aarhus Convention provisions on public participation to assess the validity of the Governance Regulation. This has since been excluded as a possibility by the Court in previous cases concerning direct effect of the Aarhus Convention provisions on access to justice.Footnote 49 In the next section, I will now turn to analyze the case study indirectly concerning the EU Taxonomy Regulation.

F. Targeting the EU Taxonomy Regulation

Besides the NECPs, the new AR has also been mobilized by other organizations to indirectly challenge the EU Taxonomy Regulation, which establishes an investment framework for those economic activities deemed environmentally sustainable and necessary to fasten the ecological transition.Footnote 50 In total, ENGOs submitted six requests concerning delegated acts adopted pursuant to the Taxonomy Regulation and their pleas present many similarities across all the requests.Footnote 51 Three of these concern Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/2139, establishing the technical screening criteria for determining the conditions under which an economic activity qualifies as contributing substantially to climate change mitigation or climate change adaptation.Footnote 52 In this regard, for the sake of simplicity, I will focus on one specific request, namely request number 64—submitted by the ENGO ClientEarth—and use it as a case study in the frame of this section.Footnote 53 This is because the Commission answered to all the requests concerning Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/2139 in the same way.Footnote 54 Therefore, I will summarize below the main substantive arguments deployed by the complainants and outline how the Commission engaged with their arguments. More specifically, I will focus on the grounds for review specific to bioenergy related activities raised by the complainants which mostly deal with scientific evidence in the climate change context.

I. A Scientific Q&A

Three challenges against Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/2139 were submitted by environmental organizations.Footnote 55 First, I want to draw the attention of the reader to the fact that this act could now be easily qualified as an administrative act within the scope of Article 2 of the AR, thanks to the reform that occurred in 2021. Indeed, prior to the reform, Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/2139 would have clearly been another measure of general application, thus unchallengeable under the Aarhus internal review mechanism. This being said, most of the arguments set forward against this EU administrative act concerned the qualification of biomass fuel as a renewable energy source. Such a challenge follows other mobilization attempts in the EU against biomass energy fuel, which have also seen other civil society organizations and individuals triggering judicial proceedings directly before the CJEU.Footnote 56 More specifically, in the request here at stake, ENGOs contested the EU qualification of bioenergy, bio-based plastics and chemicals used to make plastics, as “sustainable.”Footnote 57 This by arguing in essence that:

[B]urning forest biomass emits around as much or more CO2 per unit of energy than fossil fuels. In the EU, the GHG emissions linked to bioenergy activities are dealt with under different accounting systems, namely within the energy or land sectors. This leads to the assumption that, from the energy perspective, forest-based biomass energy is carbon-neutral. However, not all those GHG emissions are accounted for, thereby giving rise to accounting distortions and GHG emission leakage.Footnote 58

In other words, the complainants claimed that burning biomass derived from cutting trees emits as much or more CO2 than fossil fuels and the way these emissions are accounted in the EU creates distortions and GHG emission leakage. In support of this claim, the complainants set out a number of arguments. The complainants held that the Commission’s assessment that the biomass and biogas activities concerned “substantially contribute to climate mitigation” and the fact that such activities do not cause any “significant harm” to the climate objective—as required under the Taxonomy Regulation—is implausible.Footnote 59 According to the ENGOs, the Technical Expert Group (TEG)’s assessment showed that the criteria laid down in the Renewable Energy Directive II (RED II)Footnote 60 were not sufficient to ensure that the activity contributes substantially to climate change mitigation.Footnote 61 “Any technical screening criteria set under the Taxonomy Regulation should, at least, set a higher threshold for GHG emissions savings than the RED II does and restrict the eligibility to advanced bioenergy feed stocks.”Footnote 62 The complainants held that “scientific evidence provided below (grouped by themes) shows the existence of significant uncertainties and risks regarding the effect of the use of forest biomass with respect to climate change mitigation,” namely: “[F]alse assumption of ‘Carbon Neutrality’ in the use of forest biomass for the bioenergy-related activities”; “Further increases in the use of forest feedstock can result in net GHG emissions”; “Adverse effects on both the climate and biodiversity crises”; “Uncertainties about emission calculation and accounting methods”; “Uncertainties and risks arising from imported forest biomass”; “Uncertainties and risks regarding the availability and reliability of data on forest biomass”.Footnote 63

The ENGOs therefore argued that available scientific evidence provided demonstrates that the technical screening criteria built on the RED II may not be considered as based on conclusive scientific evidence and the precautionary principle insofar as they concern the use of forest biomass for the bioenergy-related activities. The European Commission answered this question in the Annex.Footnote 64 For space constraints reasons, I will focus only on the answers to the first two points listed here above.

1. On “Carbon Neutrality” In the Use of Forest Biomass

On the first point, concerning the alleged false assumption of “carbon neutrality” in the use of forest biomass for the bioenergy-related activities, the EU executive held that it is incorrect to state that “bioenergy is assumed ‘carbon neutral’ within the broader EU climate and energy framework.”Footnote 65 The Commission provided a more holistic reading of the EU regulatory framework, taking into account not only the EU Taxonomy Regulation, but also the RED II and the Land Use, Land-use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) Regulation.Footnote 66

Indeed, the Commission highlighted that biogenic emissions from the use of EU-produced forest-based feedstocks for energy are accounted by Member States in their national LULUCF inventories and towards their 2030 commitments, following the LULUCF Regulation, while supply chain emissions occurring in the EU, cultivation, transport, et cetera, are accounted under the EU Emission Trading System Directive and the sectors covered by the Effort Sharing Regulation.Footnote 67 The Commission recognized that there is a lively debate on forest bioenergy around the argument that emissions from biomass burning are not counted — zero-rating— at the point of combustion by the users of this biomass.

However, the EU executive rejected the ENGOs’ criticism toward the treatment of biomass as a renewable energy source because—as stated by the Commission—this overlooks the fact that “the EU ETS and the RED II assume zero rating of emissions at the point of biomass combustion because these emissions are already counted in the LULUCF sector, as a change in carbon stocks.”Footnote 68 The EU executive also explained the science-based origin of this approach, where it emphasized that:

[T]his approach follows the 2006 IPCC guidelines for national GHG inventories, as required by the Governance Regulation, and Commission Implementing Regulation 2020/1208, which lays down the EU’s monitoring mechanism for greenhouse gas emissions and other climate information so that the EU is able to comply with its reporting obligations under the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement. The rationale for this approach is mainly the need to avoid double counting and other practical issues.Footnote 69

As highlighted by the Joint Research Centre (JRC):

[I]n line with internationally agreed rules [under IPCC], the harvesting of biomass leads to direct emissions of carbon to the atmosphere—in other words instantaneous oxidation—unless it can be shown that the biomass enters another carbon pool, such as dead wood, litter or soil, or is used to produce HWPs (harvested wood products). In this way, biomass harvested for its use as energy is fully accounted for and reported as instantaneous GHG emissions under LULUCF. To avoid double counting, these emissions are zero-rated in the energy sector.Footnote 70

As indicated in the JRC 2021 study on the use of woody biomass for energy production in the EU:

[T]here are concrete reasons why emissions from biomass burning are not counted in the energy sector. [. . .] Counting emissions in the energy sector when the biomass is actually burnt while avoiding double counting with LULUCF would be extremely difficult. The difficulty is because, the biomass burnt for energy purposes comes from very different and complex pathways: Some is a primary wood from biomass harvested few months before (e.g. branches), some is secondary wood arising from the processing of wood harvested possibly few years before, some is waste wood from biomass harvested possibly decades before. Because the emissions and removals reported and accounted in LULUCF are based on the annual change in carbon stock (or the annual biomass gains minus losses), accounting forest bioenergy under the energy sector would imply a retrospective (and unrealistic) attribution of what is burnt to the biomass harvested in specific past years, and an ex-post subtraction of this harvested amount from the LULUCF accounting, to avoid double counting.Footnote 71

The Commission thus explained why biogenic emissions deriving from the combustion of EU-produced forest-based feedstocks are zero-rated in the energy sector. This is because such emissions are already accounted for by the MSs in their national LULUCF inventories and towards their 2030 commitments, following the LULUCF Regulation. According to the EU executive, including such emissions also in the energy sector would therefore lead to double counting. In the following section, I will outline how the Commission engaged with the argument according to which further increases in the use of forest feedstock can result in net GHG emissions.

2. Further Increases in the Use of Forest Feedstock Which Can Result in Net GHG Emissions

On the second point, concerning whether further increases in the use of forest feedstock can result in net GHG emissions, the Commission made clear that it did not dispute that in certain circumstances the use of forest feedstocks for producing energy can result in net GHG emissions.Footnote 72 Nevertheless, the Commission recalled once again that the EU legislative framework “comprised of the RED II, LULUCF Regulation and other EU legislation pertaining to carbon accounting and mandatory emissions reductions aim to account for these emissions at national level.”Footnote 73 The EU executive further acknowledged that “the impacts on climate change of solid and gaseous biomass used for heat and electricity are complex and can vary significantly—from very positive to very negative impacts, in other words reducing or increasing emissions compared to fossil fuels.”Footnote 74

However, in its response the Commission emphasized that “a growing body of scientific evidence is available to understand these impacts.”Footnote 75 A recent study carried out for the Commission, for instance, showed that as a whole, “bioenergy can make a significant contribution to greenhouse gas emission reductions, but the level of this contribution depend on the scale and type of bioenergy considered.”Footnote 76 The same study noted that, at the time of drafting:

[T]he majority of the solid biomass used for energy purposes in the EU could be considered to deliver substantial greenhouse gas benefits even when taking into account biogenic emissions, because the forest biomass that is used consists mostly of industrial residues as well as harvest residues—branches, tree tops—and traditional fuel wood. It further noted that studies show that these feedstocks generally deliver a beneficial greenhouse gas performance when compared to fossil fuels.Footnote 77

However, the Commission recalled that the RED II Impact Assessment recognized the risks associated with an increased use of bioenergy, which led the Commission itself to propose sustainability criteria for forest biomass.Footnote 78 In the light of this, the Commission rejected the ENGO’s request on the merits and its denial was then challenged by ClientEarth before the EU GC. The case is currently pending.Footnote 79

This being said, I will now set out my preliminary conclusions on legal mobilization targeting the EU Taxonomy Regulation under the AR.

II. Preliminary Conclusions

Even the ENGOs’ requests relating to the EU Taxonomy showed that, through the internal review mechanism, environmental organizations are actually trying to contest much broader policy arrangements, constituting the foundations of EU climate policy, and usually having the form of legislative acts. Formally speaking, this would not be possible under the AR, because legislative acts are excluded from the scope of the internal review mechanism. In this regard, delegated acts adopted pursuant to the Taxonomy Regulation do not qualify as legislative acts and can thus be contested through the internal review procedure. Moreover, as emphasized above, the submission of this type of requests would not have been possible under the original AR. Indeed, the Delegated Regulation adopted pursuant to the EU Taxonomy Regulation would have not qualified as an “administrative act” of “individual scope,” and the request for internal review would have thus been dismissed by the EU executive, as it was usually the case under the “old” AR. After the reform, the analysis of the requests submitted so far emphasizes that the Aarhus mechanism is being used by environmental organizations to trigger “systemic” legal mobilization, in other words a more ambitious type of legal mobilization, targeting not only individual technical decisions, but also broader policy arrangements, representing—in such a context—the legal infrastructure of the EU ecological transition, such as the Governance Regulation and the Taxonomy Regulation.Footnote 80

The easier admissibility of this type of requests—concerning measures of general application—has therefore created a crucial shift in legal mobilization in EU environmental matters. Indeed, now the emphasis is not put on the nature of the contested act, in other words on whether this constitutes an act of individual or general scope, but rather on the content of the contested administrative measure. This was very clear in all the requests submitted after the reform of the AR, including those concerning the EU Taxonomy Regulation. As showed in the description of the scientific “Q&A” between the ENGOs and the European Commission, the internal review mechanism under Aarhus can now be considered as a real scientific dispute settlement forum, where ENGOs and EU policymakers can have technical confrontations about how scientific evidence was taken into account in the adoption of a given EU administrative act. However, this case study also showed that submitting requests for internal review is often just a—necessary—preliminary step that ENGOs must take in order to then trigger litigation under Article 263(4) TFEU. In this way, ENGOs can claim to be “individually concerned” under Article 263(4) TFEU and be granted standing before the CJEU to challenge the response received by the EU institution. Indeed, obtaining more transparency on the EU environmental and climate policymaking is only a collateral effect, attained by those organizations who actually aim at achieving a much more ambitious goal, that is contesting the legality of broad EU policy arrangements, usually having the form of legislative acts, directly before the EU judiciary.

This case study also showed the high level of scientific and legal sophistication demonstrated by the ENGOs mobilizing under the new AR when contesting, on extremely technical grounds, the Delegated act implementing the EU Taxonomy Regulation. This element confirms, once again, the value of “expertise” as a key resource for triggering legal mobilization, especially in scientifically charged domains like environmental protection and climate change.Footnote 81 Below, I will now set out my final conclusions.

G. Conclusions

In this Article I wanted to provide a more empirical overview of how the “new” AR is being used by environmental organizations to trigger legal mobilization in the areas of energy and climate. The “Aarhus” reform has certainly broadened access to the internal review mechanism for environmental organizations, which can now obtain answers on the substance of a given environmental policy choice undertaken by an EU institution or administrative body. This is particularly evident from the analysis of the requests used as case studies in the frame of the present contribution.

This research has shown how ENGOs were “eager” to rely on the new internal review procedure established under the AR and amended in October 2021. Indeed, already in December 2021, a Dutch ENGO submitted a request under Article 10.Footnote 82 In fifteen years under the old AR, the Commission received forty-eight requests for internal review. In less than three years under the new Regulation, the Commission has already received forty-three requests. Furthermore, the requests that so far have already received a response from the Commission, have all been rejected. Since the reform, the Commission’s denial has been challenged thirteen times under Article 263(4) TFEU and eighteen cases—also including challenges against acts adopted by EU institutions other than the Commission—are currently pending before the GC.

A significant fraction of the requests submitted to the Commission, almost a quarter of them, concerned the EU regulatory framework governing NECPs. Ten requests coming from ten different ENGOs were submitted to the EU executive, all claiming that the EU regulatory framework requiring the MSs to adopt their ten-year NECPs did not comply with the public participation provisions enshrined under the Aarhus Convention. In support of their arguments, the claimants also relied on the findings of the ACCC in Communication ACCC/C/2010/54 and on two Decisions on EU compliance with the Convention adopted by the MOP. In particular, ENGOs argued that the EU’s failure to comply with the MOP’s decisions constituted an “administrative omission” under Article 2(1)(h) AR. The Commission deemed all the ten requests “inadmissible.” This by mainly arguing that NECPs are “national” plans, to be adopted by MSs’ authorities and that no precise administrative act to be adopted by the EU executive had been identified by the ENGOs.

On the other side, this Article also focused on the requests indirectly concerning the EU Taxonomy Regulation and the way this unlawfully labels bioenergy, bio-based plastics and chemicals used to make plastics as “sustainable.” ENGOs claimed that this inclusion breached a number of procedural and substantive principles of EU environmental and energy law. To the ENGOs’ arguments, the Commission responded with an Annex of 104 pages, engaging with the points raised by the claimants and motivating the reasons behind the contested policy choices regarding biomass fuel.

In this regard, this research highlighted how the Aarhus mechanism is now being used by environmental organizations to trigger “systemic” legal mobilization, targeting not only specific administrative decisions, but to indirectly challenge also legislative acts and broader policy measures representing the legal infrastructure of the EU ecological transition, such as the EU Taxonomy Regulation. This proves the ambition of an environmental movement which does not want to settle for solely challenging delegated acts and implementing decisions, but that rather “dreams big” and intends to re-orientate the way the ecological transition is being operationalized in Europe.

Second, this Article has shown how the Aarhus internal review mechanism has turned from being a purely “administrative” dispute settlement forum into a true “scientific” dispute settlement forum, where ENGOs and EU institutions can have deeper confrontations on the science underlying EU environmental and climate law. This was particularly evident in the analysis of the requests targeting biomass fuel under the EU Taxonomy Regulation. This type of confrontation is providing more transparency on the way science is assessed and included by the European Commission in the EU policymaking. This is because it is forcing the EU executive to adequately explain and motivate the reasons behind specific policy choices. However, no major difference has been made in terms of the outcome of the requests and effect on the initial administrative act, which was contested, because - so far - all the ENGOs’ requests have been rejected.

This has pushed the ENGOs to challenge the denials obtained by the EU institutions under the new AR and trigger litigation before the GC, as mentioned above. Considering the well-known barriers to access to justice encountered by private applicants when trying to be granted standing in actions for annulment, especially in the climate change context,Footnote 83 we can infer that the AR reform has already changed the LOS available under EU law. On the one hand, the AR forces ENGOs to take a preliminary procedural step before triggering strategic litigation, that is precisely the submission of the internal review request to the concerned EU institution or administrative body. In this way, an ENGO can easily claim to be “individually concerned” under Article 263(4) TFEU and be granted standing before the CJEU to challenge the response obtained by the EU institution. On the other hand, the new AR seems to be giving ENGOs the opportunity to contest the legality of EU climate policy measures directly before the EU judiciary. Nevertheless, it is probably too early to draw conclusions on the effectiveness of the AR reform as a mobilization pathway capable of truly empowering European ENGOs. In this regard, it will be interesting to observe how the CJEU will deal with these cases brought under the new AR and how intense its judicial scrutiny on EU climate policy measures will be.

This being said, regardless of the judicial outcome of these pending cases, this research has already shown the high level of scientific and legal sophistication possessed by the environmental organizations mobilizing under the AR. Indeed, the extremely technical mechanism of internal review laid down under the AR de facto “shapes” a specific type of actors involved in legal mobilization in EU environmental matters. Indeed, such a mechanism truly empowers only those ENGOs having adequate internal resources and technical expertise on both, scientific and legal grounds. This is because only organizations with these specific resources will be able to act as effective scientific interlocutors of the EU institutions in the environmental and climate context. This confirms the relevance of “expertise” as a key resource for triggering effective legal mobilization in environmental matters.

Finally, further research is certainly needed to shed light on the regulatory implications of the internal review requests as well as on the way the ENGOs lacking adequate resources and internal expertise, cooperate and build coalitions with experts and other organizations to compensate for their structural defections.

Acknowledgement

The views and opinions expressed in this Article belong solely to me, and do not reflect the view of the European Commission. I want to thank Marta Morvillo, Stefan Salomon and Pola Cebulak for the two wonderful workshops organized in Amsterdam on “Strategic Litigation in European Law” and for coordinating the submission of this Special Issue. I also want to seize this opportunity to thank the reviewers for their useful comments on this Article.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.

Funding Statements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for profit sector.