I

The separation of ownership and control ensures that companies are governed by professionals with the necessary skills and experience to maximise a firm's success. If this is done well, the owners or shareholders of a firm benefit because they get a return on their investment. Yet typical principal–agent conflicts arise if the managers and owners have different targets. In extreme cases, managers might only maximise their bonus, while investors are interested in short-run benefits, speculative gains, or dividends.Footnote 1 When ownership is concentrated in the hands of a few shareholders, the incentives and possibilities for those shareholders to control and monitor the management are larger. Past research suggests, however, that although the principal–agent problem is minimised by the presence of controlling owners, the controlling owners themselves may become another source of corporate governance issues (Burkart et al. Reference Burkart, Gromb and Panunzi1997). Studying who owns a firm, who controls it and the legal framework for its governance is crucial since these aspects will determine the nature of those conflicts.

Except for Britain and to some extent the United States, there is little transparency about the corporate ownership structures of joint-stock companies, because comprehensive, historical corporate ownership data is rare for most countries in this period (Burhop 2019, pp. 9–11). The available evidence, however, clearly shows that in most countries except Germany we observe a rapid decline in the concentration of ownership for the period 1875 to 1945 (Franks et al. Reference Franks, Mayer and Wagner2006; Foreman-Peck and Hannah Reference Foreman-Peck and Hannah2012; Acheson et al. Reference Acheson, Campbell, Turner and Vanteeva2015).

The information on ownership structure is the most comprehensive for Britain since firms established under the 1856/1862 UK corporate law were required to submit shareholder registers to the Registrar of Companies. Using this source, Acheson et al. (Reference Acheson, Campbell, Turner and Vanteeva2015) collected ownership data for five cross-sections for the period 1865 to 1900. They show that, in general, ownership concentration was lower in Victorian Britain in 1900 than in modern Britain (Acheson et al. Reference Acheson, Campbell, Turner and Vanteeva2015, pp. 919–21).Footnote 2 Franks et al. (Reference Franks, Mayer and Rossi2009) track the development of ownership structure of British companies over the twentieth century by drawing several random samples. They find that while from 1900 to 1960 it is possible to observe a rising dispersal of ownership, one can observe a concentration of ownership after 1960 (Franks et al. Reference Franks, Mayer and Rossi2009, p. 4035). To what extent ownership and control of US corporations have been separated is still debated (see Cheffins and Bank Reference Cheffins and Bank2009, for a review). However, ‘One of the best-established stylized facts about corporate ownership is that ownership of large listed companies is dispersed in the United Kingdom and the United States and concentrated in most other countries’ (Franks et al. Reference Franks, Mayer and Rossi2009, p. 4009).

For Germany, Franks et al. (Reference Franks, Mayer and Wagner2006) have shown that concentration of ownership remained high from the nineteenth century until the 1950s. Yet estimating the true ownership concentration in German joint-stock firms is a difficult task. This is because, in contrast to the UK and US, it is not possible to observe the universe of shareholders for certain firms because most shares in German companies have been held in bearer form. Only shareholders who attended general meetings had to register their shares. Searching shareholder lists in the archives of individual companies is quite time-consuming and it is thus difficult to sample them. Some systematic evidence is available in public archives since firms had to submit attendance lists of general meetings to stock exchange officials in case of seasoned equity offerings or similar events. Franks et al. (Reference Franks, Mayer and Wagner2006) have based their analysis of ownership structures on 156 shareholder lists from 55 companies.

Moreover, shareholders of German firms could transfer their voting rights to banks or any third party to cast votes in their name.Footnote 3 This so-called proxy-voting biases measures of ownership concentration. If we observe a banker or a bank with a large share of votes it is possible that although the shares may be counted as in the hands of one investor, they might be dispersed because the banker acts as a representative for a large number of smaller investors. More importantly, in this way banks had the power to control firms without actually owning their shares. Thus, we have a third player in the room, which is potentially problematic, because banks also hold firms’ debt, and thus proxy voting and direct equity ownership may not provide equivalent incentives for banks (Fohlin Reference Fohlin2007, pp. 58–9). The dominance of large banks has been discussed extensively in Germany's financial history. There is a classic view, associated with Gerschenkron (Reference GERSCHENKRON1962), that the peculiar character of Germany's financial institutions played a critical role in its industrialisation. According to this view, one reason was the emergence of formal relationships between universal banks and non-financial firms, a typical feature of which was the appearance of bankers on the supervisory boards of non-financial firms. This way, banks arguably acquired a high degree of control over industrial enterprises (see Burhop Reference Burhop2011, pp. 170f.; Lehmann Reference Lehmann2014, pp. 93f.). While their presence on the supervisory boards, often in financially dependent firms, has been shown, a causal impact of banks’ presence on firms’ performance or credit access could not be identified and recent research has questioned their actual impact (see, for instance, Edwards and Ogilvie Reference Edwards and Ogilvie1996; Fohlin Reference Fohlin2007; Burhop Reference Burhop2011, 170f.). Lehmann (Reference Lehmann2014) studies banks’ dominance in the underwriting process of joint-stock firms in the nineteenth century. Her article provides quantitative and qualitative evidence that although the market for underwriters was also dominated by a small oligopoly of six large banks, there was still perceptible competition among them, which kept fees and short-run profits low. This further underlines the previous findings that although German banks held large market shares and were present on many supervisory boards and other committees, the effect of their dominance seems to have been less than Gerschenkron (Reference GERSCHENKRON1962) has famously suggested. Because of the above-discussed lack of data on shareholders, the impact of banks’ presence and their impact in general meetings has not been addressed from a quantitative perspective so far.

We revisit the questions of ownership and control for the period 1869–1945 to improve our understanding of the individuals present at the general meetings of German corporations, their voting influence and therefore their potential interests. We study the socio-economic characteristics of those individuals in terms of gender and social class. Moreover, we aim to identify whether they were owners themselves or whether they acted on behalf of a bank. By estimating how many of the shares were represented by bankers, we can estimate how much control the banks could have over industrial companies through the general assembly. Overall, we collected a random sample of 782 attendance lists for 272 joint-stock firms.Footnote 4Footnote 5 This sample is large enough to provide interesting new insights into corporate control, without claiming to be representative for all German joint-stock firms.

Based on this sample, we can confirm previous research findings by showing that ownership of the firms was also highly concentrated over the whole period and firmly in the hands of a small group of influential men. Moreover, we approximate the presence and impact of banks at the meetings. In about 30 per cent of the meetings, a banker or a bank was the most influential shareholder and in more than 50 per cent of the meetings a banker or a bank was among the three largest shareholders. This share is potentially even larger since it was quite a challenging task to identify banks' representatives. Bank officials did not always openly attend with a bank affiliation. Thus, we compared the names on the lists with the names of the most important private bankers and the directors of those banks as well as with bank officials who were members of industrial supervisory boards in this period.

Moreover, we provide insights into the socio-economic characteristics of the attending shareholders and thus insights into the social structure of the corporate governance of large German firms for the period 1869–1945. Bit by bit and especially after 1923, we observe more often shareholders from the middle class at the general meetings in absolute numbers, although only with small vote shares.

We also find more female representation after 1919, at the same time as women's rights improved.Footnote 6 However, after 1933, the National Socialists again restricted these rights. Women were confined to the roles of mother and spouse and were excluded from all positions of responsibility, notably in political and academic spheres. During the Weimar Republic, women appeared more often at general meetings than before, but their ownership of shares remained very low. Although in the nineteenth century only a few women were present at the meetings, they held comparatively large shares. In our sample, the actual voting power of women was with about 4 per cent higher in the sample that covers the nineteenth century than in any other subsequent period. Moreover, 98 per cent of female investors in our sample were only engaged in a single firm. Overall, despite our observation of greater participation among women in the Weimar Republic, their increased political power was clearly not accompanied by a rise in economic power – at least not in our sample.

As well as being interesting in terms of German corporate history, inequality and social history, learning about the socio-economic characteristics is also interesting from a finance perspective, since they matter a great deal for investment decisions.Footnote 7 Studies testing reactions to historical events on stock markets can therefore only infer whose reactions they are actually testing.Footnote 8

We also show that some of these observed findings seem to follow some general patterns. Ownership dispersion, for instance, seems to have been generally significantly lower for the largest companies as well as for those that were located further away from a stock exchange. On the other hand, broader access to capital, i.e. listing on multiple stock exchanges, seems to have reduced the concentration.

The main part of the article is organised as follows. Section II provides a short overview of the legal framework of corporate control in Germany and how legal and political factors influenced the composition of shareholders and their control. Section III introduces our dataset and gives a basic descriptive analysis of our sample of investors over time. In Section IV we calculate the concentration measures of owners who were present for each period. In this section, we also provide the shares that were represented by banks and bank officials. Section V focuses on the socio-economic characteristics of the investors, i.e. gender and social class. In Section VI we investigate general patterns of ownership and control. Section VII concludes.

II

In the period under consideration from 1869 to 1945, we observe five major legal changes that influenced investor protection, the ownership structure of joint-stock firms and the role of management and supervisory board.

The first was the introduction of the German stock corporation law amendment (‘Aktienrechtsnovelle’) in 1870. It contained regulations that allowed the shareholders to independently control the founding process of joint-stock firms and the management board. It made clear that the decision-making authority was held by the general assembly, i.e. the shareholders. They had to decide on changes to the articles of association, including increases and reductions of equity. The general assembly was also able to limit the power of the management board to certain areas. Furthermore, the general assembly decided on the audit and approval of the balance sheet and income statement. It was also allowed to elect the supervisory board (Selgert Reference Selgert2021, pp. 35ff.). However, the regulations were not binding for the articles of association, so the contractual freedom was barely restricted. Many companies established supervisory boards as their centre of power. The rights of the shareholders were limited because the law made it possible to transfer the decision-making authority (on capital increases and articles of association) to the supervisory board. The general assembly did not play the intended role of controlling the supervisory and management board, because the supervisory board could also elect the management board (Burhop Reference Burhop2006, p. 3 and Reference Burhop2009, pp. 578f.; Selgert Reference Selgert2021, pp. 37f.). Voting rights at the general meetings were exercised according to one share, one vote. The power to exercise the voting right, however, could be limited by a minimum number of shares. Shareholders who wanted to participate at a general meeting had to deposit their shares beforehand. Sometimes the meetings were called so late that shareholders would not have enough time to deposit their shares.Footnote 9 Furthermore, the law made no regulation about dividend payments to the shareholders. All in all, investors’ protection was very low and the law was mostly in favour of the founding families (Selgert Reference Selgert2021, pp. 38ff.).

In 1884, the shareholder rights were strengthened and the power of management and supervisory board was reduced. The decision on changes to the articles of association and the decision on an increase or decrease in the share capital was now the task of the general assembly. Non-shareholders could also be elected to the supervisory board, which means that it was possible to establish independent control of the management. Moreover, shareholders were granted individual and minority rights. For instance, an individual shareholder could now sue against a resolution of the general assembly if it violated the law or the articles of association. Furthermore, a minority of shareholders could request a special audit of the activities of the managing directors. Nevertheless, the supervisory board remained the central organ of power. It was still possible for the supervisory board to control the management, because the articles of association could transfer certain decision-making powers to the supervisory board (Selgert Reference Selgert2021, pp. 41ff.). However, participation at the general assembly was simplified. Every general meeting had to be announced at least two weeks in advance. If shares needed to be deposited, this also had to be announced in time (Selgert Reference Selgert2021, pp. 41ff.).

In the reform of the Commercial Code 1897, only minor changes were made in terms of investor protection. The supervisory board remained the central organ of power and, essentially, shareholder rights remained at the level of 1884 (Selgert Reference Selgert2021, pp. 46f.). Companies had to inform the shareholders of the date of the general assembly as well as about resolutions and motions, for example. Important changes had to be announced two weeks in advance. Minority shareholders could still demand a general meeting, but were then obliged to bear the costs of convening it. In addition, the principle that each share had to grant at least one vote was maintained. Theoretically, however, it was now possible to control the general meeting with the help of multi-voting shares, which only made up a small part of the share capital. With the same par value as the ordinary share, these shares have multiple voting rights. There was also a new regulation about the hierarchy of dividend payments. Dividend payments had to be at least 4 per cent of the company's revenue, and only afterwards could the supervisory board receive a share in profits.

The stock corporation law was further developed in the Weimar Republic when the rights of the management board were strengthened again. This was a reaction to the period of hyperinflation that saw an increase in the number of shareholders who held shares only for speculative reasons. Thus, there was an incentive for the management to create voting rights that guaranteed the control of the firm. This was achieved with the creation of protective shares (often in the form of multiple voting shares), which allowed major shareholders or the management board to control the general assembly with little capital investment. Owners of these protective shares were mostly members of the founding family, banks or members of supervisory and management boards (Beer Reference Beer1999, pp. 156ff.; Selgert Reference Selgert2021, pp. 51ff.). According to figures from the Statistical Office of the Reich, in 1925 almost 54 per cent of the stock corporations that were traded on a German stock exchange had multiple voting shares.

Some further resolutions were introduced at the beginning of the 1930s. Most important was the creation of an auditor, who was elected by the general meeting. This auditor examined the accuracy of the balance sheet and the annual financial statements. Shareholders thus had more detailed information at their disposal on the basis of which they could decide whether it was worthwhile for them to continue their commitment to the company. However, the law of 1931 did not improve the shareholders' active influence on strategic decisions within the company. It focused more on increasing transparency (Selgert Reference Selgert2021, pp. 43ff.).

Legislation during the Nazi period reduced the power of the general meeting by taking away the right to appoint and dismiss the management board, to take decisions on management and to approve the annual financial statements. These competencies were transmitted to the supervisory board, which was still elected by the general assembly (Selgert Reference Selgert2021, pp. 61ff.). Multiple voting shares were prohibited. However, according to Selgert (Reference Selgert2021, pp. 64f.), the status quo of investors’ protection of 1884 was no longer achieved.

III

As mentioned in the introduction, ownership data for Germany is in short supply since until recently most shares in German companies were in bearer form and traded anonymously. Only those shareholders who attended the general meeting of the firm were required to register their names and shares. With the Stock Exchange Act of 1896, companies were legally bound to submit information about shareholders attending general meetings to the respective stock exchange on which their shares were listed (Franks et al. Reference Franks, Mayer and Wagner2006, pp. 542 and 554).Footnote 10 Thus, it is possible to obtain these lists and therefore information on the structure of the participating shareholders after 1896. For the period before 1896, we have to rely on the voluntary provision of information. These meetings, however, were not the ordinary annual meetings but special meetings called for a particular reason, such as to focus on the rise or reduction of the share capital. Still, even after 1896 when the meetings were reported every year, the archives only kept a sample of lists. However, we can expect that for reasons of representativeness the archives kept a random sample.

The data on the meetings were collected from the Hessian Economic Archive (Hessisches Wirtschaftsarchiv), the Bavarian Economic Archive (Bayerisches Wirtschaftsarchiv), the Baden-Württemberg Economic Archive (Baden-Württembergisches Wirtschaftsarchiv), the Historical Archive of Deutsche Bank AG and the Historical Archive of Commerzbank AG.Footnote 11

Overall, we collected 782 shareholder lists from 272 companies, covering basic information on 9,970 individual and institutional investors. The data include filings of the Berlin, Hamburg, Cologne, Düsseldorf, Essen, Augsburg, Mannheim, Frankfurt, Munich, Stuttgart and Breslau stock exchanges. We extract the name of the company, the industrial sector, the location of the headquarters and the place where the general assembly took place. Data on the share capital of a company and the stock exchanges on which the company's shares were listed are taken from the Handbuch der deutschen Aktiengesellschaften. The Handbuch has only been in existence since 1896, but based on the information it contains, we are able to calculate the share capital for general meetings that took place before 1896. The shareholder information includes the name of each shareholder or institution, and his/her/its city of residence. In most cases, the gender can be inferred from the name. Not all lists reveal the same degree of information. In many cases, only the name and residence of the shareholders are reported, and information on occupation or sectors is missing. In some cases, the address was also left blank. For about 55 per cent of the lists of general meetings, we have information on the number of shares owned and the number of votes that investors were able to cast. For about 25 per cent of the lists, we only have information on the vote shares and for about 12 per cent of the lists, we only have information on the owned capital. For 8 per cent of the lists, information on votes and owned capital is missing completely.Footnote 12, Footnote 13

As mentioned in Section I, some investors did not use their right to influence firm decisions directly by attending the general meetings but instead transferred their voting rights to their bank. In the pre-war era, proxy voting was established in two ways. The first does not bias measure of ownership concentration: shareholders could transfer their voting rights (Stimmrechtsermächtigung), allowing the bank or any third party (often also the voting rights were transferred to lawyers) to cast votes in their name.Footnote 14 In these cases, the shareholders had to reveal their identity, and these details are available in the lists of the general meetings. We will show in the section on concentration (see Table 5) that the group of shareholders that transferred their right to vote did not differ from the typical shareholders that attended the meeting. The second way, which was more important in practice, was the so-called Bankenstimmrecht or Depotstimmrecht. According to Fohlin (Reference Fohlin2007, p. 122), many banks required their customers to transfer their votes automatically upon opening securities accounts, giving the banks widespread control over rights of equity stakes they did not own. As discussed in Section I, banks could do more or less whatever they wished with these voting rights, without being actual owners of the shares (see Fohlin Reference Fohlin2007, pp. 122–4 and also Selgert Reference Selgert2021, p. 55). We will address the questions of the power of banks by providing information on the share of votes that were represented by banks or bankers.

For a subsample of 4,269 shareholders, we also have quite detailed information on title and occupation, which makes it possible to classify the investors into social classes.

Table 1, panel A reports the number of companies, the number of general assemblies and the number of shareholders divided into six time periods with significantly different economic conditions and/or political systems. The period 1869 to 1913 covers the meetings that took place during the Empire, 1914 to 1918 covers the meetings during World War I, and 1919 to 1923 covers the meetings in the first years of the Weimar Republic, with high levels of inflation resulting in the hyperinflation of 1923. The period 1924 to 1928 covers the meetings that took place during the Weimar Republic, which was characterised by relative economic and political stability but ended with the Great Depression in the subsequent years 1929 to 1933. Our last period covers the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler and World War II. We did not treat World War II separately because trading became very restricted during the Nazi regime until 1945.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

Sources: Various; see Appendix.

a Some investors did not use their right to influence firm decisions directly, but often transferred their voting right to a representative. In this table, we count all shareholders. This number is often larger than the number of persons that actually attended the meeting. In many cases, a banker represented more than one shareholder and the information on the actual shareholders is provided in the lists.

Overall, our sample contains 272 joint-stock companies with 9,970 investors attending 782 general assemblies. The number of meetings and firms in our data set varies with periods. In the first period, we observe 112 general assemblies of 44 firms with 1,855 investors. The number of general meetings drops during World War I and then rises to 101 firms, with information on 3,349 investors attending 150 general assemblies, in the period of the ‘Golden Twenties’. This number drops again after 1933 to 39 firms, with information on 795 investors and 73 general assemblies. It is clearly not possible to draw reliable conclusions about changes in the ownership structure of firms over time, because each period is based on a different sample. We aim at learning more about changes over time in the last section of this article, applying regressions with firm fixed effects to study the within-firm variation over time.

Overall, quite a large share of the share capital was present at the meetings with on average about 57 per cent.Footnote 15 In the Empire years, however, the average attendance seems to have been much lower than in the period of the Weimar Republic. This fits the observations made by Fohlin (Reference Fohlin2007, pp. 122–4) and Franks et al. (Reference Franks, Mayer and Wagner2006). It also fits the legal framework during that period. As discussed in Section II, it was difficult for smaller shareholders to participate at a general meeting before 1884. Even though it was easier after 1884, attendance of smaller shareholders remained rather was low (see also Burhop Reference Burhop2004, p. 36). Fohlin (Reference Fohlin2007, p. 124) also cites Richard Passow (Reference Passow1922), a contemporary observer who lists some explanations for the low attendance rates at shareholder meetings. Fohlin summarises Passow's ideas as ‘rational apathy’ among small shareholders: the cost of travelling to locations where the meetings took place, insufficient time to attend, the sense that news coverage provided sufficient information for small shareholders, and the presumption among small shareholders that their influence was limited. Thus, cheaper transport costs, a greater desire for first-hand information and an increasing acceptance of female shareholders were all potential drivers of the higher attendance that we observe in our sample at meetings during the Weimar Republic.

Table 1, panel B reports some further characteristics of our sample selection. On average we collected lists of three meetings per company over a period of about four years. Overall, about a quarter of our sample was not (yet) listed on a stock exchange (see Table 2). This number is fairly stable over time. Only in the Nazi period was this number relatively high. In this period many firms were forced to delist. Roughly, about half of the sample was listed on a regional stock exchange and about a third was listed on a regional stock exchange and in Berlin. Only a small part of our sample (about 1 per cent) was listed in Berlin only. This is certainly driven by the fact that we observe many firms from the south of Germany, which often listed in Berlin and on a stock exchange in the south such as Munich or Stuttgart. Table 2 also provides information about the sectors. Our sample consists mainly of banks, firms from the heavy and light industries, and breweries. The highest number of firms comes from the light-industrial sector. This category includes textiles, paper, glass and rubber.

Table 2. Description of the sample

Sources: Various; see Appendix.

Figure 1 shows the headquarters of the firms in our sample. We do have a slight bias towards the south, but also cover firms from other important areas of Germany such as the industrial Ruhr area, Berlin and Frankfurt. Most importantly, Figure 1 shows that the geographical bias of the sample is relatively stable over the different periods.

Figure 1. Regional distribution of sample by period

Sources: Various; see Appendix.

Note: The maps depict Germany with different state borders according to our six observation periods. These examples are for illustration purposes. We are aware that the border demarcations changed during our observation period.

Altogether, although the sample is still rather small compared to the universe of German firms in the period under observation and varies over time, we cover the general meetings of a large variety of middle-sized and larger firms from different sectors that were listed in Berlin and regional stock exchanges. Thus, this unique sample is well suited to provide new and yet undiscovered insights into the ownership and governance structure of German joint-stock companies in this period.Footnote 16

IV

In this section, we calculate the concentration of owners, who were present, for each period. Although more than 50 per cent and sometimes up to 70 per cent of the capital was present, this was represented by a very small number of attending shareholders (Table 3). In the sample before 1913, the mean number of shareholders was 24. This number was slightly smaller with about 15 for the meetings during World War I. In the period between the hyperinflation and the Great Depression it was slightly higher and lowest in our sample covering the Nazi regime. The median was lower and more stable over the different samples, at about 11. Similar to Franks et al. (Reference Franks, Mayer and Wagner2006), we find that the maximum number of investors is mostly above 100, showing that the source is perfectly capable of identifying firms with large numbers of shareholders and more widespread shareholdings. The largest number of shareholders appeared at the 1927 general meeting of Allianz Versicherungs-AG, a large insurance company headquartered in Berlin and with a share capital of 30 million Reichsmark. At this meeting, 582 investors were present, representing about 27 per cent of the companies’ total shares. Another example is the general meeting of Mannesmannröhren-Werke, a large steel producer headquartered in Berlin and with a share capital of 6 million Reichsmark. At this meeting in 1932, 282 investors were present, representing 46 per cent of the company's share capital. A few meetings were held between only two investors. Usually, these were smaller companies that were not (yet) listed. One typical example is the general meeting of the pencil producer Faber in September 1898, three years after it had been transformed into a joint-stock company and about two months before the firm started trading on the Berlin stock exchange. At this meeting only two of the founder's family members were present, representing 83 per cent of the share capital. Overall, we collected five more lists of general meetings for this company. By 1911 the numbers of shareholders present had increased to 11 and by 1928 there were 68 shareholders in attendance.

Table 3. Ownership concentration over time

Source: See Appendix, authors’ own calculations,

Note: Some investors did not use their right to influence firm decisions directly, but often transferred their voting right to a representative. In this table, all calculations are based on the number of persons who actually attended the meeting. For example, if we have the information that one attending person was the representative for one or more shareholders, we count all shares for one person.

In Table 3, we also report different measures of ownership concentration. For each period, we use the same measures as Franks et al. (Reference Franks, Mayer and Wagner2006) in their seminal article. These are C1, C3 and C5 – the combined votes of the largest, the three largest and the five largest shareholders, respectively. Cthreshold is defined as the minimum number of shareholders necessary to cast 25 per cent of the present votes, and Herfindahl is the overall distribution of represented capital/votes cast per general meeting.Footnote 17 Similar to Franks et al. (Reference Franks, Mayer and Wagner2006), the concentration was fairly stable across our sample period. Indeed, if anything, concentration seems higher in the samples that cover later periods. On average, the largest shareholder held about 47 per cent of shares, which means that, in most cases, this investor alone could provide more than the threshold of 25 per cent of the votes – i.e. most firms had one shareholder who controlled the firm. C3 and C5 also indicate a strong concentration of power in only a few hands. Over the whole observation period, we rarely find firms with widespread share ownership. This is also reflected in the Herfindahl Index.Footnote 18 Given that the median number of investors is fairly stable, the fact that more capital was represented at the shareholder meetings in the later years may indicate a rising concentration in the form of a growing number of shares owned by the attending investors, not a rise in the number of smaller shareholders attending the meetings.

These first findings show that German joint-stock firms were mainly controlled by small groups of shareholders or their representatives and that this was fairly stable over the different samples. Very few firms have had a more widespread share ownership at a general meeting. In the next step, we learn more about the most influential investors. Figure 2 shows the percentage of shareholdings of inside shareholders and whether they were among the largest, and therefore most influential, shareholders. Inside shareholders are classified as members of the management board (Vorstand) or the supervisory board (Aufsichtsrat), as well as the founders of a company and members of the founding families. We identified members of the founding families based on the names. Thus, these estimates constitute the lower bound of the share of family members, since we cannot identify members that changed their name due to marriage in the generations to come.

Figure 2. Power structure among inside shareholders

Sources: Various; see Appendix.

Overall, all three groups of inside shareholders were highly represented at the meetings. On average, about 21 per cent of the share capital was held by inside shareholders. It is also interesting to note that the probability of investors attending such meetings was higher for those who lived in the same region in which the general assembly took place (see also Neumayer Reference Neumayer2018). However, larger shareholders who had a strong voting impact also travelled longer distances – thus, it is unlikely that travel costs significantly influenced control of the firms.

However, the numbers of inside shareholders in our sample vary between the periods. The share capital of management shareholders was the highest during the period of the Golden Twenties (about 8 per cent). This fits the observation of Selgert (Reference Selgert2021, p. 57) that the management board became more important during this period. The supervisory members also held, on average, about 9 per cent of the present capital, and the founders and their family members, on average, about 9.5 per cent. In our sample, however, members of a founding family seem to have had the highest influence in the period during World War I. This value is again smaller in the sample directly after the War, but again higher in the following periods. In the years 1929–33, founding family members held, on average, 10.6 per cent of the present capital. Only during the Nazi period was their share really small. This is likely to have been a consequence of the expropriation of the property of Jews and other victims and opponents of the National Socialists. However, please note that the decrease in the capital share of founding families may also be related to name changes in the decades after the foundation.Footnote 19

Figures 2b and 2c further show that inside shareholders were indeed able to strongly influence a firm's fate. In more than 30 per cent of the meetings, an inside shareholder held the largest share, and in more than 48 per cent at least one inside shareholder was among the three largest shareholders. The dominance of management and supervisory boards is also noteworthy. There is very little separation between executive power and control in the general meetings and, more importantly, this seems to be persistent over the 60 years of our observation period. Although shareholder rights were strengthened after 1884, management and supervisory board were still the central organs of power. This is reflected in the high share of inside traders.Footnote 20 At the same time, the figure shows that many joint-stock corporations changed from owner-led companies to more manager-led companies.

Moreover, we try to improve our knowledge about the influence of banks by identifying banks and bank representatives at the meetings. As discussed above, the option of proxy voting often gave the banks a large number of votes, although they did not actually own the shares. We approximate the impact of banks as far as possible. This is done by first counting all shares that were represented by a bank representative. Moreover, in some cases, we have information about the occupational status of the shareholder. We also count the share if the occupation indicates that the shareholder was a banker or a lawyer working for a bank, even if we do not know for which bank or whether he was there to represent his own shares or the bank's shares or proxy vote shares. In most cases, there was no information about the occupational status. However, a bibliographical search on the individuals that appear at the meetings of more than one firm revealed that banks would often send a representative who would appear on the list under his own name, not indicating that he was attending on behalf of a bank. Thus, it is possible that if we rely on the provided occupation or announced representation only, we underestimate the influence of banks. We therefore compared the names on the list with the names of the most important private banks and their directors (an overview of the most important private banks in the twentieth century can be found in Wixforth and Ziegler Reference Wixforth and Ziegler1997, p. 220, and Ziegler Reference Ziegler2003, p. 44). We also compared the names on the lists with the names of the most influential bankers and private bankers who were members of industrial supervisory boards (see Wixforth and Ziegler Reference Wixforth and Ziegler1997, p. 221.).

Figure 3 provides an overview of the shares that we were able to trace back to banks – note that here we have excluded the meetings of banks and focus only on the meetings of non-financial firms. Clearly, the figure confirms that banks were very influential over all periods. In about 30 per cent of the meetings, a banker or a bank was the most influential shareholder and in more than 50 per cent of the meetings a banker or a bank was among the three largest shareholders. This influence was fairly stable over the sample periods and potentially even larger if we assume that there were also individuals working for a bank, who we could not identify.

Figure 3. Banks and bankers among the most influential shareholders

Note: We count all shares that were represented by a bank or a banker (information taken from the attendance list). Moreover, we identified more bankers, who most likely were present on behalf of a bank, by comparing the names on the list with the names of the most important private banks and their directors (an overview of the most important private banks in the twentieth century can be found in Wixforth and Ziegler Reference Wixforth and Ziegler1997, p. 220, and Ziegler Reference Ziegler2003, p. 44). We also compare the names on the lists with the names of the most influential bankers and private bankers who were members of industrial supervisory boards (see Wixforth and Ziegler Reference Wixforth and Ziegler1997, p. 221). Please note that for this figure, we excluded the meetings of banks.

To highlight the difference between ownership and control, we estimate the upper bound of dispersed ownership. This is done by assuming that all the shares represented by a banker or a bank and all capital that was not present at the general meeting was in fact owned by small shareholders. Table 4 provides the percentage share of attending capital that was represented by a bank or a banker, the average share of capital that was not present and the combined estimate of potentially dispersed capital. The share of capital represented by banks was firmly stable over the samples; however, the overall turnout at the meetings seems to have increased. Thus, the upper bound of the share of the capital that was potentially dispersed, which was 60 per cent on average, seems to have declined.

Table 4. Estimates of shares that were either absent or potentially represented by a banker/bank

a Assuming that all shares represented by a bank or banker and all capital not present at a general meeting was in fact owned by small shareholders.

Overall, German joint-stock firms were controlled by a small number of influential shareholders. This is stable over the different samples in the different periods. Inside shareholders and banks in particular could easily control the fate of the companies. If anything, the concentration of power seems to have increased over time, although this may be driven by a sample selection bias. We will try to address this issue in the last section. Moreover, although it seems contradictory, it is likely that ownership was actually quite dispersed but that this did not translate into power due to the proxy voting of banks, which concentrated the voting power in their hands without actually owning shares. We cannot judge whether they actually used the power. According to Selgert (Reference Selgert2021, pp. 52f.), contemporaries reported that banks often voted in the interests of management.

V

Until now, the socio-economic characteristics of German shareholders have not been studied in a quantitative way.Footnote 21 Other studies that provide information on the social structure of shareholders covering our observation period study British and American shareholders (Green et al. Reference Green, Owens, Maltby and Rutterford2011; Ott Reference Ott2011; Rutterford Reference Rutterford2012; Rutterford et al. Reference Rutterford, Sotiropoulos and Van Lieshout2017; Sotiropoulos and Rutterford Reference Sotiropoulos and Rutterford2018).

We primarily use names to identify gender and to establish whether an investor was an individual or an institution. Following this procedure, we observe a total of 666 female investors, of whom 23 were classified as widows. Furthermore, we observe 9,321 male investors and 1,362 institutional investors. In four cases, married couples were mentioned as investors. We assigned these cases to female investors under the assumption that the wives had a say if they were named. In 45 other cases, we only have information that a representative of a group of heirs or communities acted as investors. These are summarised in the category ‘Unspecified’.

These total numbers certainly underestimate the impact of institutional investors, since while most other investors appeared only once or twice, some institutional investors appeared every year for more than one firm and held larger shares. This is better reflected in the shares of votes per period (Table 5, panel A).

Table 5. Gender and social class: average vote share of the whole group and sample comparison

Sources: Various; see Appendix.

Table 5 shows the average share of votes for the different groups. In most cases, we have the number of votes for each investor. If we do not have the number of votes, we assume that the share of capital equals the share of votes. Overall, the majority of vote shares in our sample were held by male investors (about 54 per cent). In comparison, only about 3 per cent of the vote shares were held by women. It is interesting to note that women held the highest shares during the period of the German Empire; this also corresponds to the proportion of shares held by women present at the general meetings. In this period about 3 per cent of the investors present at the meetings were women, who held about 4 per cent of the votes. In the period after 1923, the proportion of women attending the meetings rose to nearly 10 per cent, which translated into only about 1.6 per cent of the votes.Footnote 22 The low proportion of female shareholders is not surprising and fits well the observation that only a few women were actively involved in large companies (see, for instance, Hlawatschek Reference Hlawatschek1985).Footnote 23

Altogether, cross-ownership is rare in our sample. Most shareholders appeared only at the meetings of one firm (92 per cent) and about 5 per cent at the meetings of two firms. Moreover, these numbers are relatively stable over the observed periods.Footnote 24 Only eight women held shares in more than one company. These women were often members of the founding family or married to prominent industrialists. Anna Langheinrich, for instance, held shares in Graphitwerke Kropfmühl AG in 1925. In that year she was also the official director of Graphitwerke Kropfmühl AG and therefore one of the few female entrepreneurs of the time (see Deutsches Aktienhandbuch 1925, p. 549). Two further examples are the female shareholders of the Papierfabrik August Koehler AG in Oberkirch and the Papierfabrik Wilhelm Euler in Bensheim. With Anna Maria Goetz and Wilhelmine Rettner we see two women of the founding families who were members of the supervisory board of both companies, since both companies had holdings together (Krämer Reference Krämer2007).

Overall, about 9 per cent of the men held shares in more than one company. However, most of them only held shares of one more company. The men who invested in more than five firms were mostly bankers: Hermann Scholz, Otto Kleesattel, Richard Brosien as well as Albert Katzenellenbogen. Albert Katzenellenbogen was a member of the executive bodies of banks, textile companies and chemical groups in various German cities. As chairman of the board he directed the Mitteldeutsche Creditbank and later also the Commerzbank AG (see Graf Reference Graf2007, pp. 453–4 or Reitmayer Reference Reitmayer2011 or Herbst et al. Reference Herbst and Weihe2004, pp. 29 and 327). The other men who held shares in more than five firms were entrepreneurs: for example, Georg Gaill, who was a famous cigarette manufacturer, or Hugo Himmer, who was a factory owner (see e.g. Volz Reference Volz1930, p. 517).

We then classify the investors into social classes depending on occupation and academic title. Thereby, we follow the existing classification scheme outlined by Schüren (Reference Schüren1989, p. 313). Schüren defined this very detailed classification scheme in order to study social mobility in Germany in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. His work represents one of the largest and most comprehensive investigations into the possibilities for socio-economic ascent and descent in two centuries of German social history. His classification is intertemporally valid and finds consensus among social historians such as Hartmut Kaelble and Jürgen Kocka (see Schüren Reference Schüren1989, p. 313). Based on occupation, Schüren (Reference Schüren1989) distinguishes four main groups: the working class, the lower middle class, the upper middle class and the upper class. The working class contains unskilled and skilled workers, craftsmen, skilled industrial workers, and lower civil servants and employees. The lower middle class contains small farmers, merchants, masters/hosts and middle civil servants and employees. The upper middle class contains full-time farmers, entrepreneurs of medium-sized firms, senior civil servants and top officials. The upper class contains mostly landowners, large manufacturers, top academics and senior officials. The classification scheme is very detailed and even very particular occupations are easy to categorise since Schüren provides the classification for more than 6,500 occupational groups. In instances where we only have information about the title of an investor (e.g. Prof., Dr, Ing.), we classify their occupation based on the title. For most cases this was relatively easy, because most of the titles are academic titles that we can easily assign to the group of academics and the upper class. We also assign investors with a title of nobility (e.g. Exzellenz, Graf, Freiherr von) to the upper class, even if there is no indication of their profession in our data.

In total, the sample contains 4,269 investors for whom we have information about their occupation. The majority came from the upper class (90.53 per cent of the observed investors). About 7 per cent of 4,269 came from the upper middle class, 3 per cent from the lower middle class, and only 0.06 per cent from the working class.Footnote 25 Looking again at the vote shares of the different groups, we find that the vote share from the upper class seems to have been the highest for all groups. Table 5 reveals that in the nineteenth century, control of the company's strategic decisions was clearly in the hands of men of the upper class. This changes only slightly in the 1920s, when ownership became increasingly available to the lower social classes, which is reflected in the higher shares of investors from the higher and lower middle classes. If we consider that the overall turnout increased, it is possible that the ownership did not change but that more people from the middle class decided to use their vote in the general elections. Moreover, this does not necessarily mean that poorer classes did not own shares at all, merely that they were not represented at the general meeting. It is likely that the shareholders who held a small share of capital and who came from the lower social classes did not attend the meetings because of the travel costs or because their influence was too small to give an incentive to attend. Some may have been represented by bankers.

The votes in Table 5, panel B do not sum up to 100 because of the institutional investors, some of which were banks. As mentioned earlier, shareholders could transfer their voting rights for a particular meeting to a bank (Stimmrechtsermächtigung), allowing the bank or any third party to cast votes in their name. In contrast to the proxy voting in these cases, the shareholders had to reveal their identity and this was recorded in the lists of the general meetings. Table 5, panels C and D show the characteristics of the shareholders that transferred their right to vote compared to the characteristics of the full sample. Overall the differences are not large. However, men and companies more often transferred their right to vote. We do not observe a higher vote share of lower social classes transferring rights, in fact the opposite seems true. The group of represented shareholders seems to have a higher likelihood of belonging to the upper class.

In Table 6 we look at the institutional investors in more detail to get a better idea of their profile. Here, we divide the investors into different industries, following Lehmann-Hasemeyer and Opitz (Reference Lehmann-Hasemeyer and A2019).Footnote 26 The highest percentage (52.06) of institutional investors comes from the banking sector, which is surely driven by the proxy voting. Thus, the banks held substantial control over joint-stock firms through proxy voting, as described above. All other institutional investors were fairly equally distributed among sectors. Some companies held shares in more than one firm. In most cases, this was banks. However, we also find large mining companies, such as the Metallgesellschaft AG from Frankfurt am Main or the Gelsenkirchener Bergwerksverein.

Table 6. Institutional investors – descriptive statistics

Source: Authors’ own calculation.

Note: The sectoral classification is from Lehmann-Hasemeyer and Opitz (Reference Lehmann-Hasemeyer and A2019, p. 79). The heavy industry category contains engineering firms, metalworking and railway requirements. Light industry contains the textile sector, paper industry, glass industry and rubber industry. Food processing contains breweries and mills. Public utility contains electricity, gas and water. Diverse contains hotel companies, terrain companies and mortgage banks.

Altogether, rising democracy and price disturbances after the period of hyperinflation were accompanied by investors from lower social classes turning up at the meetings. Their share of votes, however, remained low.Footnote 27 Although, initially, we observe a drop in the share of female investors after the hyperinflation, the share steadily increases again in the years to come. However, their influence remains low. Thus, while these observations support the hypothesis that stocks became more available to other social classes and women, they also confirm that the joint-stock firms were still firmly in the hands of a few investors from the upper class, and of institutional investors, which were mostly banks.

VI

Overall, the descriptive statistics show little variation in the ownership/governance structure of firms over the whole observation period of 77 years. The firms in our sample were securely in the hands of men of the upper class. Inside shareholders and banks also controlled large shares. Moreover, the evidence suggests that – if anything – ownership dispersion declined over time. However, we may be missing patterns of variation due to a selection bias of our sample between the periods.

To address this issue and to learn more about overall patterns, we aggregate the data at the level of general meetings and test some hypotheses that might explain different levels of power concentration. More precisely, since we observe, on average, about three meetings per firm, we construct an unbalanced panel, where the identifier is the firm and the time variable is the year of the general meeting. Thus, we are able to run regressions with firm fixed effects to learn more about changes over time that are only within-firm changes.

We closely follow Acheson et al. (Reference Acheson, Campbell, Turner and Vanteeva2015), who tried to find patterns of ownership concentration in Victorian Britain and test hypotheses to explain patterns in the ownership structure. The variables that we aim to explain in our multivariate regressions are the logs of the percentage of capital and/or voting rights held by inside shareholders, the percentage held by the largest five shareholders and the Herfindahl Index.

The first variable that we expect to impact the ownership structure is the size of the firm. Large firms need more capital. We assume that the acquisition of capital increases the overall number of shareholders and consequently lowers ownership concentration. Furthermore, we expect new shareholders, particularly from lower social classes that buy shares for the first time, to have less information than experienced investors. Thus, they might be drawn to large and well-established firms. We use the log of the share capital as a measure for size.

With a similar argument, we assume that firms listed on more stock exchanges had a more dispersed ownership. We use several dummies to test this hypothesis – one dummy that is equal to one if the firm was listed on a regional stock exchange, another dummy that is equal to one if the firm was listed in Berlin, and another dummy that is equal to one if the firm was listed in Berlin and on at least one regional stock exchange. We also control for the total number of stock exchanges the shares were listed at. Similarly, we also include a dummy variable if the firm was headquartered in Berlin. We assume that firms located in Berlin had a more diffuse ownership, since they potentially had access to a larger capital market and a larger number of investors.

Moreover, the sector might be significant (Demsetz and Lehn Reference Demsetz and Lehn1985). Companies located in an industry for which it is more difficult to assess and monitor managerial performance should have a more concentrated ownership. This is more likely to be the case in financial institutions (due to asymmetric information) and, for instance, in mining industries, which were often located further away from stock markets. Thus, we use sector dummies to identify sectors in which the ownership is particularly concentrated or dispersed. We also control for type of meeting (ordinary vs extraordinary). We also include several period dummy variables, to see whether there is an overall trend or whether there are huge differences between the different periods of investors’ protection as outlined in Section II.

The results are reported in Table 7. The first four regressions report the OLS regressions, regressions (5) to (8) the ones with firm fixed effects revealing determinants of within-firm variation.

Table 7. Regression results

Standard errors clustered by firm, *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1

The first interesting result is that, in contrast to the findings of Acheson et al. (Reference Acheson, Campbell, Turner and Vanteeva2015), vote concentration and size seem to be related, but not in the way we had expected. The larger a firm, the higher the concentration of capital present at the meetings seems to be. In the OLS regressions, size has a positive and significant impact on the capital of the five largest shareholders, as well as a positive and significant impact on the Herfindahl Index. In the fixed effects regressions (5) to (8), we observe a similar effect, albeit less significant. The share of capital held by the largest five investors rose with the rise in share capital if we consider within-firm variation. The large German joint-stock firms that were the major players in the German economy were firmly in the hands of a small group of industrialists.

Access to capital also seems to matter. Firms that were listed on a stock exchange seem to have had inside shareholders, with a lower overall share of votes (regressions (1) and (5)) and a more dispersed ownership structure (regressions (3), (4) and (8)).

The sectoral structure, however, does not really influence the ownership structure (not reported). Banks and insurance companies were the only sectors in which we observe a robust effect. The ownership structure here was more dispersed. However, insurance companies were often not traded freely on the market. They often issued vinkulierte Namensaktien – i.e. registered shares with restricted transferability (Gelman and Burhop Reference Gelman and Burhop2008, p. 49). These results should therefore be treated with caution.

In terms of regulation, we introduced dummies that control for differences in the legal framework. From 1897 onwards, investors’ rights were strengthened, but the period dummies show that ownership concentration even rose in our sample, in particular, if we look at the within variation (regressions (5) to (8)).

Altogether, we find some interesting patterns in our sample: the largest companies seem to have a less dispersed ownership structure than smaller firms. Ownership concentration even seems to decline with rising size. On the other hand, broader access to capital – i.e. listing on more stock exchanges – partly offset the rise in concentration. Sectors seem to matter little. Other firm- and meeting-specific variables also do not seem to matter. Most importantly, a better legal framework, more transparency and improved investor protection did not reduce ownership concentration – at least not in our sample.

VII

Previous research has shown that in most countries except Germany, we observe a rapid decline in the concentration of ownership of joint-stock firms for the period 1875 to 1945 (Franks et al. Reference Franks, Mayer and Wagner2006; Foreman-Peck and Hannah Reference Foreman-Peck and Hannah2012; Acheson et al. Reference Acheson, Campbell, Turner and Vanteeva2015). We revisit the questions of ownership and control of joint-stock firms based on a randomly selected unique data set for the period 1869 to 1945, covering a selection of 782 general meetings of 272 firms and information on 9,970 individual investors.

We contribute to our knowledge about shareholders and ownership concentration in three ways: first, based on our larger sample, we can confirm previous findings from Franks et al. (Reference Franks, Mayer and Wagner2006) that the concentration of power remained high, regardless of political, economic and legal conditions. Overall, the joint-stock firms in our sample were controlled by a small number of influential men, who were in most cases inside shareholders. Moreover, it turns out that the largest companies in our sample had a higher capital concentration at the general meetings than the smaller ones. This was only partly offset by the fact that better access to capital via stock exchanges led to a more dispersed ownership.

Second, we provide new insights into the socio-economic characteristics of the shareholders by studying the share of women and lower social classes. Although we find that ownership among the lower social classes and women steadily increased in absolute numbers, their share of ownership remained low and did not translate into power.

Third, we estimate the impact of banks. We do find that in about 30 per cent of the meetings, banks were among the largest five shareholders. Since it is not always possible to identify a person as a banker, this is the lower bound, and banks’ impact is likely to have been higher. This also means that although control was concentrated in a few hands, it is likely that the actual ownership – not the control – was quite dispersed. It simply did not translate into power due to the proxy voting of banks. It is difficult to judge from our analysis whether and how banks used this power. Similar to studies on the supervisory board presence of banks, we can only provide information on the scope of possibilities of the banks to influence a firm's fate. We do not know whether they used the power. To do so, we would need to study the decisions and the decision-making process at the general meetings. However, the protocols are in most cases not available and if they are, there are no votes on important topics cast by name. However, considering the findings from previous research (see, for instance, Edwards and Ogilvie Reference Edwards and Ogilvie1996; Fohlin Reference Fohlin2007), where no causal impact of banks’ presence on supervisory boards on firm performance or credit access could be identified, it is certainly possible that banks did not abuse their voting power at the general meetings.

How do our findings relate to the picture of the development of the German stock exchange and its shareholders? Burhop, Chambers and Cheffins (Reference Burhop, Chambers and Cheffins2018) have recently made a strong case for Germany having a well-regulated stock market and argue that this was a major reason why the Berlin exchange was able to compete with other international stock exchanges in the nineteenth century (see also Hannah Reference Hannah2019, table 1, p. 173). In particular, they emphasise shareholder protection and voting powers as well as good listing requirements. They do not specifically refer to the fact that large joint-stock banks were controlled by a small group of wealthy shareholders and banks. Moreover, recent papers have further emphasised that some of the shareholders were often well-connected and influential (Lehmann-Hasemeyer and Opitz Reference Lehmann-Hasemeyer and A2019). Perhaps this particular feature of the German stock market gave the joint-stock firms an advantage because the wealthy governed them very well. This could have been because they had aligned incentives (big shareholdings) as well as information and power advantages due to the fact that large shareholders were often bankers, founding family members, management or supervisory board members of the firm and/or other firms in the same sector. Arguably this was superior to the Anglo-Saxon model of more dispersed ownership with often badly informed and powerless investors. This fits the observation that many public companies in the US, such as Uniroyal, privatised in the 1990s to avoid fundamental and powerful financial manipulation, management greed and reckless speculation (Jensen Reference Jensen1989). Moreover, the recent success of firms such as Amazon, for which Jeff Bezos is not only the CEO but also the largest shareholder, further supports the hypothesis that a clear separation of ownership and control is not always superior.

Appendix

A1: Archive sources and signatures of archive files

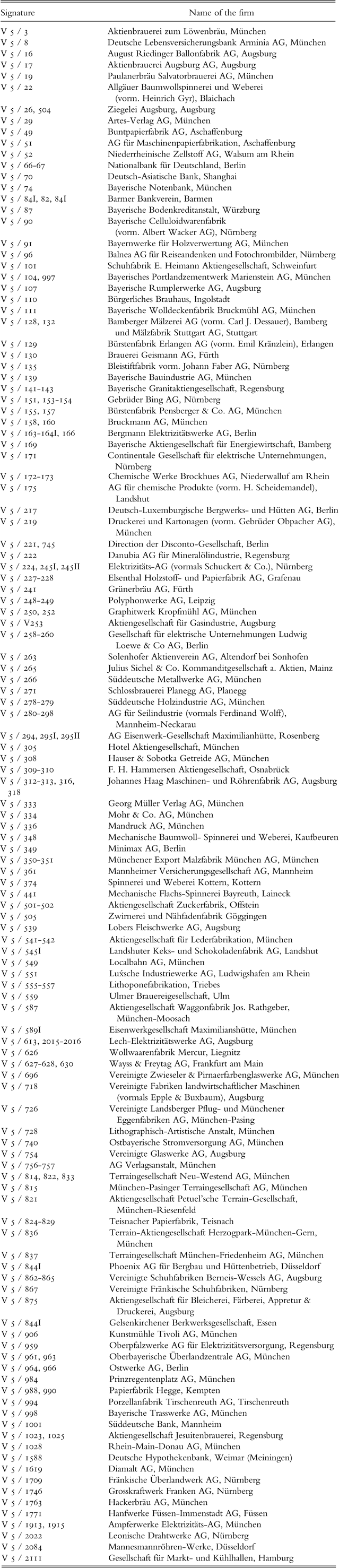

Baden-Württemberg Economic Archive (WABW)

Bavarian Economic Archive (BWA)

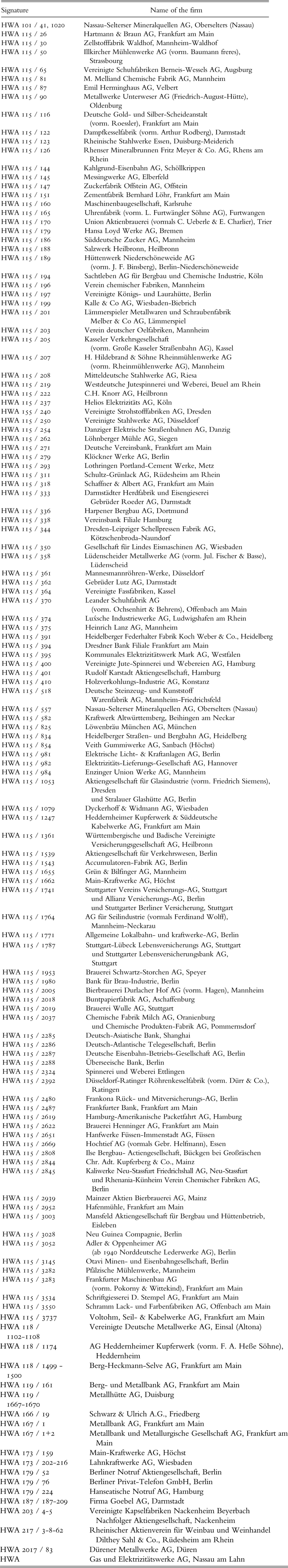

Hessian Economic Archive (HWA)

Historical Archive of the Commerzbank AG

Historical Archive of the Deutsche Bank AG

A2: Tables

Table A1. Cross-ownership (percentage)

Table A2. Firm characteristics by sector and period, firm listed in Berlin compared to sample

Table A2 gives an overview of our sample compared to the structure of all firms that were listed in Berlin for the sample years 1913, 1925 and 1938, as documented by the Handbuch der deutschen Aktiengesellschaften, a stock market manual. We calculated t-tests for size and age of firms by industry and by periods if we have more than 10 firms in our sample for the given time period and industry.

In 1913, the firm age and the total share capital do not differ statistically between the two samples. For the period 1919–32, the t-tests show that we observe, on average, slightly younger firms, but this is only driven by a few sectors. However, in this period, on average, we seem to observe larger firms. This is a result of inflated capital during the hyperinflation of 1923 and again does not apply to all sectors. The t-test of panel C again shows that our sample is representative in terms of age, but that we observe slightly younger firms.

Table A3. Gender and social class, based on number of individuals – not vote shares – descriptive statistics and sample comparison