Ever since the emerging market crises of the mid 1990s, a multitude of research has been conducted on the relationship between capital mobility and financial instability. While international finance to developing countries was generally welcomed, the turmoil in Mexico in 1994 and Asia in 1997–8 showed that surges and shifts in the movement of capital flows might hinder macroeconomic management and create significant financial risk. Indeed, sudden inflows of foreign funds can lead to strong exchange rate appreciation, exacerbate asset price bubbles, or generate currency, maturity and interest rate exposure in the balance sheets of the corporate and banking sectors. The question has therefore been about better ways to handle international capital flows and policies that could help to safeguard the financial system and the economy from their potentially harmful, destabilising effects.Footnote 1

The role of prudential regulation and capital controls has received a great deal of attention within these debates. As crisis countries in emerging markets had gone through processes of external financial liberalisation and deregulation, scholars have investigated the conditions and circumstances under which capital mobility could become a source of instability and result in full-scale meltdowns. Though open and unregulated capital accounts may not necessarily pose special risks or be at the root of financial problems, they can represent a major threat if not properly instituted and framed. In the presence of macroeconomic imbalances, shallow capital markets, and underdeveloped private sector's risk-management practices, all of which are common features of developing economies, the importance of supervisory and regulatory policies to deal with financial instability has been widely acknowledged among academics and policymakers (Eichengreen and Mussa Reference Eichengreen and Mussa1998; Henry Reference Henry2007). Yet whether these measures work in practice and how they vary across time, space and institutional settings remains a key subject of discussion in the literature.

In much of this research, the banking sector and its foreign activities have been given special focus. Because the business of banks is liquidity transformation, their involvement with international finance can create major vulnerabilities for the domestic financial system, as the global financial crisis of 2007–8 demonstrated. Indeed, heightened reliance on short-term foreign borrowing, engagement in long-term lending, and the occurrence of currency and interest rate mismatches, will most likely result in increased financial fragility. Therefore, prudential regulation and supervision of the domestic banking sector, such as capital requirements or ceilings on foreign exchange operations, along with controls on the inflow of capital such as unremunerated reserve requirements of external funding, may help to limit the scope for risk-taking by banks when intermediating foreign capital with domestic borrowers and thereby mitigate the likelihood of financial crises.

This article investigates the relationship between international banking, regulatory frameworks and financial fragility in Brazil and Mexico at the time of the Latin American debt crisis of 1982. In the lead up to 1982, as the Euromarkets developed and the petrodollar recycling process that followed the oil shock of 1973 surged, large volumes of capital flew into the developing world, with Brazil and Mexico being the major recipients. While mainly intermediated by commercial banks from advanced industrial economies, the domestic banking sectors of debtor countries themselves were also involved in borrowing and lending activities in the international capital markets. During this period, Brazilian and Mexican banks did indeed become increasingly internationalised and involved in the external indebtedness and bank-lending boom that culminated in the crisis. With the Mexican default in August 1982, and subsequent external debt repayment problems in Brazil and other developing economies, international credit flows came to a sudden stop and generated a new phase of domestic financial instability, generating a crisis of historical proportions – the well-known Latin America ‘lost decade’.Footnote 2

In the quest to explain the financial fallouts of 1982, national regulation and supervision of international banking and capital flows in debtor countries have often been overlooked. A comparative study of the Brazilian and Mexican experiences is particularly interesting for at least three main reasons. First, not only were Brazil and Mexico two of the major emerging economies and borrowers in the world capital markets at the time, but their banking systems and leading commercial banks were among the largest in Latin America and the broader developing world that were partaking in the process of financial internationalisation. Second, although their banking industries had a similar size, market structures and external obligations, the framework for the participation of domestic banks in the Euromarkets and the intermediation of foreign capital with domestic borrowers was fundamentally different. While no capital controls or provisions on the banks’ operations abroad existed in Mexico, a stringent set of rules governed the inflow of capital and the foreign business of domestic banks in Brazil. Finally, whereas Mexican banks’ involvement with foreign finance caused severe banking problems in the wake of the 1982 debt crisis (Alvarez Reference Alvarez2019), no major bank failure or systemic meltdown occurred in Brazil, which raises the question of the impact of regulation and international banking on financial fragility that lies at the core of this article.

The voluminous scholarly literature on the Brazilian and Mexican crises of 1982 has been mainly concerned with macroeconomic fundamentals and has highlighted factors such as growing public deficits, external account imbalances and dizzying monetary expansion.Footnote 3 In this article, I focus instead on the situation of the domestic banking systems and delve into the distinctive features and vulnerabilities of the models of international financial intermediation employed by commercial banks in both countries. The article shows that, despite a larger number of domestic financial institutions involved with foreign finance and an arguably greater international footprint in scale and scope, the Brazilian banking system was considerably less exposed than its counterpart in Mexico and argues that a main underlying reason for their contrasting ability to weather the crises is to be found in their different regulatory structures. The model of international banking intermediation that evolved out of a regime of heavy-handed bureaucratic control in Brazil resulted in lower risks than the one developed in Mexico, which had a more self-regulating approach. The study reveals the potential benefits of capital controls and prudential regulation and how they can help to mitigate risks and protect financial stability. My account relies on a collection of sources that includes a large variety of documents and quantitative evidence from the business and financial press, unpublished reports and dissertations, central banks’ yearbooks and monthly bulletins, banks’ balance sheets and financial statements, and the historical archives of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY), Bank of England (BoE) and Lloyds Bank.

The article begins by reviewing the historical context of bank internationalisation and the main features of the banking industry in both countries. It then analyses the models of intermediation, with a detailed examination of financial instruments used and the transformations and risks undertaken by the banks when channelling foreign capital into their home countries. The next section looks specifically at the foreign agencies and branches of Mexican and Brazilian banks, the nature of their activities, and the different risks and vulnerabilities underlying their business. Section IV analyses the exposure of Brazilian and Mexican banks to the debt crisis and the repercussions of the defaults on their liquidity and solvency positions along with the extent to which this represented a threat to the stability of the domestic banking systems. The last section concludes with a discussion about the importance of the findings beyond the scope of this study and its implications for future research.

I

The end of the Bretton Woods system and the relaxation of capital controls in the early 1970s invigorated the development of the Euromarkets for international banking and initiated a surge of foreign lending. By end-1982, the cross-border liabilities in domestic and foreign currencies of Bank for International Settlements (BIS) reporting banks had grown to about US$1.6 trillion from less than US$200 billion ten years earlier, and the market moved from encompassing some hundred banks from a few countries to over one thousand internationally (Schenk Reference Schenk, Cassis and Bussière2005). This process of banking internationalisation, which accompanied an expansion in the network of offices overseas and a rising presence in major financial centres, led to a growing volume of foreign currency transactions and the importance of international business in banks’ balance sheets and domestic economic activity (Pecchioli Reference Pecchioli1983; Bryant Reference Bryant1987). While largely concerned with banks and the banking systems of industrial countries, the developing world was not an exception to this trend, and Brazil and Mexico were two of the largest developing economies participating in this process of the internationalisation of banking.

Figure 1 plots the evolution of the external position of the banking system in both countries, namely cross-border liabilities to foreign financial institutions in terms of domestic economic activity. In Brazil, recourse to foreign capital by domestic banks took off in the late 1960s, increasing from US$92.5 million in 1967 to US$2.2 billion in 1973 and US$18.4 billion in 1982 – 0.3, 2.9 and 6.5 per cent of the GDP respectively, an average expansion of 42.3 per cent per year over the whole period. The bulk of these liabilities consisted of the so-called Resolution 63 operations, an external borrowing statute introduced by the Brazilian financial authorities on 21 August 1967 to enable banks to obtain funds in the international capital markets and on-lend domestically, but there were also trade-related and exchange obligations.Footnote 4 In Mexico, this process started almost a decade later and essentially concerned the use of short-term credit lines to fund international loans (Alvarez Reference Alvarez2019). Between 1975 and 1982, Mexican banks’ external liabilities escalated quickly from US$717 million to US$10.2 billion – 0.7 to 8.7 per cent of the GDP respectively, which represents a dizzying increase of 71.4 per cent per year on average. These developments took place, however, within national financial systems with important differences regarding the legal framework and mechanisms by which commercial banks acquired funding through global networks and the presence of foreign banks.

Figure 1. Foreign banking liabilities in Brazil and Mexico, 1967–82

Source: Banco de Mexico's Annual Reports and IMF's IFS Yearbook 1983.

The involvement of Mexican and Brazilian banks with international finance was embedded in the development strategies and import substitution policies undertaken by their home governments. In both countries, as in other Latin American economies, these were the late years of state-led industrialisation, and foreign debt and bank financing were critical to these processes.Footnote 5 In Brazil, financial reforms instituted by the military, which governed the country after a coup in 1964, controlled the inflow and outflow of foreign capital by invoking Law 4.131, and its associated Resolution 63.Footnote 6 Between 1967 and 1982, when the Brazilian GDP tripled and considerable amounts of foreign capital flowed into the country, the financial system significantly expanded and strengthened its presence in the domestic economy.Footnote 7 Commercial banks, as the most prominent domestic financial institutions in the country – commonly the leaders of larger financial conglomerates – developed a predominant role in the investment process. With almost every sector of the economy relying on external finance, the banking sector increasingly resorted to foreign borrowing and were able to steadily expand their lending, becoming a central segment of international financial intermediation (Frieden Reference Frieden1987). Governments and state-owned corporations as well as private industrial firms and foreign companies were among the beneficiaries of Brazilian banks’ externally funded credit lines.

Although less spectacularly than Brazil, Mexico also experienced a process of burgeoning economic growth coupled with heavy reliance on the international capital markets and bank finance. During the Echeverria and Lopez Portillo administrations between 1970 and 1982 when public and private sector borrowing in the Euromarkets flourished, the Mexican GDP more than doubled and domestic banks came to play a greater role in supplying the country's rising demand for credit.Footnote 8 Following the financial reforms of 1975–6, the Mexican banking sector strengthened its base of loanable funds and expanded its credit portfolio – both in absolute and relative terms – by increasingly funding its operations abroad.Footnote 9 But unlike Brazil where the external borrowing activities of domestic banks evolved out of, and in the terms defined by, central bank resolutions, Mexican financial authorities did not set or regulate the channels and instruments for the intermediation of foreign capital with local borrowers. The internationalisation of Mexican banks emerged instead in a rather lax normative institutional and regulatory framework and developed in the absence of official guidelines or specific legal provisions.

The growth and internationalisation of the domestic banking systems paralleled an increased concentration of the industry and consolidation among the leading banks of each country. Both the military regime in Brazil and the PRI administrations in Mexico encouraged the amalgamation and integration of the sector. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Brazilian government adopted a series of measures, such as the suspension of the issuance of new charters and the creation of a merger commission (Cofie) among others, that prompted a wave of mergers and acquisitions which led to a sharp reduction in the number of banks and an increase in their size and scope.Footnote 10 A similar process was under way in Mexico, where government policies to stimulate the transformation of banks into larger units were introduced in the late 1960s and were further promoted with the multiple bank reforms of the mid 1970s. This new legislation, which allowed for the integration of different financial firms into commercial banks, brought about a large number of mergers among medium and small banks and a consolidation of the banking system around a smaller number of bigger entities (del Angel Reference Del Angel2002, Reference Del Angel2003). At a time in which name and size were central factors in determining the ability of financial institutions to participate in the world capital markets, these changes were to favour the development and build-up of overseas operations by the big national banks.

Indeed, the Brazilian and Mexican banking systems were similar in size and market structure and they were also both largely concentrated among the main banking institutions of their respective countries. Table 1 exhibits the volume of assets of the banking sectors and the six largest banks as of end-1982 along with their corresponding external liabilities. In Mexico, total banking assets reached US$51.1 billion, US$33 billion or 64.7 per cent of which related to Banamex, Bancomer, Banca Serfin and Multibanco Comermex, the country's major private financial institutions, along with the majority state-owned Banco Internacional and Banco Mexicano-Somex. These six banks were also responsible for US$7 billion or 69.1 per cent of the US$10.1 billion of the sector's total foreign borrowing. As for the Brazilian commercial banking system, total assets stood at US$59.8 billion and Banespa, the large bank of the state of São Paulo, together with the privately owned Bradesco, Banco Itaú, Banco Nacional, Banco Real and Banco Economico, controlled up to US$25.1 billion or 42 per cent. In terms of the external indebtedness, these banks accounted for about US$5.6 billion or 26.4 per cent of a total of US$21.2 billion in Resolution 63 and other foreign obligations for the entire commercial banking industry.Footnote 11 The last column illustrates the degree of reliance on foreign borrowing as a source of funding, which was considerably larger for Brazil than Mexico at a consolidated level, but quite similar for the group of the six largest institutions, although with significant variation among banks.

Table 1. The Brazilian and Mexican banking sector in 1982

Sources: Brazil: Banco Central do Brasil's monthly bulletin and Revista Bancária Brasileira; Mexico: Banco de Mexico's annual reports and CNBS's monthly bulletin.

A further dimension of the internationalisation of the Brazilian and Mexican banking systems relates to the activities of foreign financial institutions in those countries. Although under strict access policies, international banks could establish themselves and operate in Brazil, while they were legally prohibited from conducting direct banking activities in Mexico. As of 1982, several major US and European banks, such as Chase Manhattan, Bank of America, Deutsche Bank and others, had branches or subsidiaries in Brazil and were able to engage in domestic and foreign operations on the same terms as any local institution in accordance with banking law.Footnote 12 They could therefore participate in international business and conduct cross-border operations under Resolution 63, thus accounting for about a quarter of the liabilities of the commercial banking sector in 1982 (Biasoto Junior Reference Biasoto1988, p. 203). In contrast, foreign banks willing to have a physical presence in Mexico were only allowed to open a representative office, which could not perform direct banking activities.Footnote 13 The only way for them to conduct business in the national territory was by leveraging the network of correspondent banking relationships with local banks. They could also facilitate international operations between parent banks in their home countries and a Mexican bank but could not process cross-border transactions independently. The extent of the financial operations of international banks in Mexico was, therefore, more limited than in Brazil.

II

The intermediation of foreign finance with domestic borrowers conducted by Brazilian and Mexican banking occurred within a different institutional and regulatory structure for capital mobility. In Brazil, the inflow of credit and broader external borrowing activities of the domestic private and public sector were regulated by Law 4.131 and complementary legislation, which established maturity rules and other financial conditions (i.e. de facto capital controls) that framed and shaped the international operations of domestic banks under the supervision of the central bank.Footnote 14 Conversely, as leading public officer and external debt negotiator Angel Gurría stated, ‘Mexican authorities had never regulated, controlled or required the registration of any form of Mexican private sector contracted debt with foreign entities’ (Gurría Reference Gurría and Griffith-Jones1988, p. 78). The lack of capital controls and government policies on international financial flows meant that Mexican banks had considerable room to devise, and engage in, the business and overseas operations that were most suitable to their interests as long as they fell within the law and the consent of financial authorities. These two contrasting approaches implied therefore that, while the model of external financial intermediation in Mexico resulted mainly from the free decisions and criteria of the banks, that of their Brazilian counterparts was largely conditioned to regulatory constraints.

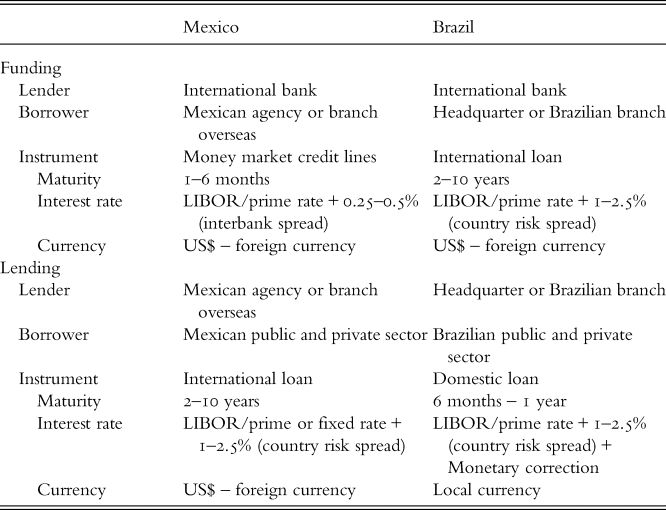

Table 2 depicts the main features of the models employed by Mexican and Brazilian banks when intermediating foreign capital with domestic borrowers. A first apparent point of difference relates to the location of the banking offices that carried on the operations. While in Brazil banks borrowed abroad through headquarters or branches in the national territory under the provisions of Resolution 63 – which accounted for about two-thirds of commercial banks’ foreign liabilities (see Figure 1) – the main operating arm of Mexican banks in the international capital markets was their network of overseas agencies and branches. As of end-1983, the foreign offices of Mexican banks, which were largely concentrated in the United States, London and the offshore financial centres of the Caribbean, accounted for about 70 per cent of the total external liabilities of the sector and the remaining 30 per cent corresponded to head offices or branches in Mexico. Whether the office intermediating between foreign capital and domestic borrowers was situated either in the country or abroad in a major world financial centre is important because it involved funding and lending methods with different maturity, interest rate and currency structures, resulting thereby in different types and levels of risks.

Table 2. Foreign borrowing and lending models of Mexican and Brazilian banks

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

In both countries domestic banks borrowed from international banks operating in the Euromarkets, but the fundraising instruments were fundamentally different. Where the foreign agencies and branches of Mexican banks funded themselves in the international money markets through interbank transactions, their counterparts in Brazil contracted international loans – i.e. syndicated or direct Eurocredits. A key distinction between these two funding lines concerned the duration: wholesale money was essentially short-term – usually ranging from overnight up to six months – while Eurodollar loans were medium and long-term operations of two to ten years. The use of international loans by Brazilian banks was grounded on regulatory requirements about the maturity of foreign borrowing operations. Initially set at a minimum of two years in 1972, the Brazilian central bank frequently amended the legislation and modified the limit in accordance with the needs of foreign exchange and external debt repayment profiles, progressively imposing longer tenors up to ten years. The central bank also regulated the reimbursement schedule by establishing minimum grace periods, which could range from six to 18 months, as well as the time between instalments, depending on the maturity of the loans.Footnote 15

Furthermore, the terms of the loans that Mexican and Brazilian banks granted with those external funds, and thereby the maturity transformation involved, were in complete opposition. In the case of Mexico, the bulk of the money that the foreign agencies and branches raised in the international Eurocurrency markets was used in project finance through the provision of direct or syndicated loans to the Mexican public and private sectors (Alvarez Reference Alvarez2015). In Brazil, on the other hand, the proceeds of Resolution 63 borrowings were on-lent domestically for working capital to cover customers’ short-term operational needs or fixed investments, and the maturity of these so-called ‘repass loans’ could not exceed that of the external obligation.Footnote 16 Thus, where Mexican banks incurred dangerous mismatches by funding long-term international loans with very short-term credit lines, the Brazilians invoked the reverse maturity operation – long-term liabilities funding shorter-term assets. The balance sheets that resulted from these two intermediating strategies were therefore structurally different, generating considerably higher levels of risk in the case of Mexico. The wholesale nature of Mexican bank borrowing and the external loans to home country customers made their funding base more volatile and their financial position more vulnerable to shifts in international capital markets’ conditions and defaults.

From a microeconomic perspective, these borrowing and lending operations represented two alternative mechanisms of arbitrage between domestic and foreign markets’ interest rates. Figure 2 shows the spread between the average cost of domestic funding and the interbank interest rate in the Eurocurrency market adjusted by the depreciation of the Mexican peso against the dollar. With high domestic interest rates, two-digit level inflation, and a virtually fixed nominal exchange rate between 1977 and the devaluation of February 1982, the incentives for private capital flows into the country and for domestic agents to borrow abroad in foreign currency (rather than domestically in pesos) were considerable.Footnote 17 In this context, Mexican banks raised dollars in the international money markets at LIBOR or prime rate plus a small interbank premium of 1/8–1/4 per cent and then charged a larger country-risk spread of 1.5–2.5 per cent on the international loans plus the fees and commissions on the operation, representing a lending margin of 1.25–2.25 per cent. An additional advantage was that, unlike domestic pesos or dollar deposits, the funds that Mexican banks’ foreign agencies and branches realised in the international capital markets were not subject to reserve requirements either in Mexico or in the host country, which further diminished the relative cost of external borrowing but increased the risk. At the sector level, the share of domestic deposits in the funding base dropped from about 80 to 65 per cent between 1977 and 1982, while credit lines from foreign banks rose from 3 to 20 per cent over the same period.

Figure 2. Domestic vs foreign costs of funding in Brazil and Mexico, 1977–82

Note: Mexico: spread between the average annual interest rate of domestic bank fundraising instrument (pesos) and the 1–3-month Eurodollar deposit rate (US$) adjusted by monthly devaluation; Brazil: spread between effective annual interest rate of descontos and Resolution 63 repass loans as published in Revista Exame.

Source: Banco de Mexico's series Financieras Historicas, Revista Exame (several issues).

The extent of Brazilian banks’ engagement with international finance also relied on relative domestic–foreign credit cost considerations within a system of crawling-peg exchange rate and financial indexation. Figure 2 plots the spread between the effective rate for working capital financing through the discounting of commercial papers (desconto), which was the main credit instrument of commercial banks funded with domestic resources, and Resolution 63 lending. After a period of domestic interest-rate ceilings in 1979 and 1980, the cost of money through descontos was hiked up when the government freed the deposits on lending rates in the late 1980 while simultaneously introducing tight credit growth limits, with Resolution 63 loans becoming the cheaper option as the spread between them increased.Footnote 18 Through Resolution 63, Brazilian banks borrowed abroad at LIBOR or prime plus a country-risk spread which they were then allowed to pass on to the domestic borrower (along with other charges associated with the foreign loan) plus a commission, which was the banks’ benefit margin. The repass loans had to be granted in cruzeiros and the final borrower was to assume the currency risk under assurance by the central bank of foreign exchange availability. As in Mexico, although temporarily affected by compulsory deposits with the central bank in 1972–4, Resolution 63 borrowing was not subject to reserve requirements or directed-credit programmes as domestic deposits, providing the banks with more flexibility of usage and allocation. Between 1967 and 1982, as inflation escalated up to three-digit levels and the deposit base of the commercial banking sector progressively deteriorated, Resolution 63 obligations grew from nil to 20 per cent of total liabilities.

Along with these maturity, payment schedule and pricing regulations, Brazilian financial authorities established a set of additional prudential rules for Resolution 63 operations. On the liability side, the regulation imposed an upper limit on the level of foreign loans that the banks could borrow abroad, which was initially set at two times the paid-in capital and free reserves, and then increased to four times in 1980. On the asset side, only companies engaged in industrial and commercial activities were eligible for the repass loans, excluding service industries in the financial sector such as investment brokers or insurance companies. Importantly, the banks could on-lend the entire amount to one borrower or divide it among several companies up to a limit of no more than 10 per cent of their capital level in subloans to a single borrower. The Brazilian central bank's Foreign Capital Supervision and Registration Department (FIRCE) was responsible for processing the Resolution 63 applications and supporting documents submitted by the banks as well as authorising the operations.Footnote 19 These requirements were enforced by the Banking Inspectorate (ISBAN), which conducted monthly inspections on banks’ balance sheets and their foreign operations. In contrast, no such legal guidelines and provisions, gearing ratios, or supervisory office existed in Mexico to regulate and oversee the way domestic banks were conducting their international borrowing operations and the inflow or outflow of foreign capital.

III

Along with the expansion of cross-border transactions under Resolution 63, the internationalisation of the Brazilian banking sector also involved the creation of agencies and branches overseas as in the Mexican scenario. As of the beginning of the 1970s, apart from Banco do Brasil that, as the main financial agent of the Federal government and instrument of its external commercial policy, had been developing a large and widespread network of foreign banking offices, only Banco Real and Banespa had a direct presence abroad. This situation would, however, quickly evolve over the following decade as an increasing number of banks opened their own international facilities, and by the end-1982, 18 leading Brazilian public and private banks had agencies or branches overseas.Footnote 20 In Brazil, the opening of foreign offices by a domestic bank was subject to minimum capital and reserve requirements and formal authorisation by the central bank,Footnote 21 as opposed to Mexico where the international expansion of the banks was overseen by the Secretary of Finance with no specific limitations or requirements.

Although more geographically diversified in the case of Banespa and Banco Real, the presence of Brazilian banks abroad, as paralleled by their counterparts in Mexico, was largely concentrated on international financial centres. The United States, and in particular New York with its large dollar money market, was their main destination and, to a lesser extent, London, which had become the epicentre of the international Eurocurrency market. As of 1982, all Brazilian and Mexican banks with an international presence were operating in New York and some had additional banking offices in Los Angeles, Miami or San Francisco, with a total of 25 and 10 US agencies or branches respectively as of year-end. Furthermore, four out of the six Mexican banks and four out of the 18 Brazilian banks operating in the US also had a branch in London. The new offshore financial centres or banking outposts of the Caribbean, namely the Cayman Islands and the Bahamas, were also among their destinations, and all six Mexican banks and 12 Brazilian banks had a presence there as well. The arrival of Mexican and Brazilian banks in the US, London and the Caribbean was part of a broader international trend of strong expansion of foreign banking presence in the world's main financial centres over the period.Footnote 22

Table 3 lists the Brazilian and Mexican banks in the United States and London along with the year of arrival in the country and the volume of business as of June 1982. The table shows the relatively larger and more aggressive involvement of Mexican institutions in the US banking market during the 1970s and early 1980s and also, though to a lesser extent, in London. By the time Bancomer and Banamex established themselves in the US in 1974, Banespa and Banco Real, the two major international Brazilian banks with the largest US involvement, were already operating there, but by mid 1982 the assets of these two Mexican banks were double those of their Brazilian counterparts. At an aggregated level, the ten US agencies of Mexican banks had reached US$2.9 billion in assets, an amount 45.9 per cent higher than the US$1.9 billion of the 19 Brazilian banks by June 1982. In London, the assets of Mexican and Brazilian banks were about US$2.1 and 1.3 billion respectively, which also indicates the relatively faster pace with which Mexican banks, especially Banamex, Bancomer and Serfin, expanded their operations in the UK given the fact that they had initiated business there some years later than Brazilian banks. Overall, the size of the average Mexican banking office in the US and London was 2.3 and 1.2 times larger than that of the Brazilian counterpart respectively. Although beyond the scope of this article, the extent of the US and London activities of Banco do Brasil, whose assets were significantly larger than that of the total network of other Brazilian banks operating there, should also be underlined (see Table 3).

Table 3. Brazilian and Mexican banks in the US and London, June 1982

Note: assets are in million US$; NY (New York), CA (California), and FL (Florida); A (agency) and B (branch).

Sources: FFIEC 002 Report; The Banker; Bank of England archive.

A main reason why the US and London were appealing destinations for Mexican and Brazilian banks, as well as for many other foreign banks, was direct access to international wholesale funding. In the case of Mexican banks, money market instruments and interbank transactions represented virtually the totality of the resources of the agencies and branches in the US, which was then used to fund international loans to customers back in their home country (Alvarez Reference Alvarez2015). As for Brazilian banks, information provided by their US banking offices in the FRBNY's FFIEC 002 Report shows a similar balance sheet structure and financial intermediation model for Banespa. As presented in Table 4, borrowed money from financial institutions, federal funds and interbank deposits accounted, respectively, for 54.4, 16.6, and 10.1 per cent of the US$653 million in total liabilities as of June 1982, or as much as 84.1 per cent in total. On the other side, the loan portfolio represented about US$ 491 million or 75.1 per cent of total assets, of which about three-fifths consisted of commercial and industrial credits and the remaining two fifths was lending to financial institutions. Like any international bank, the overseas banking offices of Brazilian banks could lend to borrowers in Brazil under the statute prescribed by the law, and Banespa used these channels to finance Sao Paulo private companies and public sector projects as part of the development strategy of the state government. Data collected by Freitas shows that as of December 1982, Resolution 63 loans and syndicated or direct credits under Law 4.131 represented an estimated 21.2 and 20.7 per cent respectively of the portfolio of its international agencies and branches. The balance consisted of 19.4 per cent in export and import finance to Brazilian customers and 42 per cent of claims with non-Brazilian borrowers, while on the liability side as much as 92.6 per cent were interbank facilities.Footnote 23

Table 4. Asset and liability structure of Mexican and Brazilian banks in the US, June 1982 (million US$)

Note: Mexican banks include Bancomer, Banames, Serfin, Somex, Comermex and Internacional; Other settled up to 1980 includes Comind, Economico, Itaú, Mercantil de SP, Nacional and Unibanco; Other settled in 1981–2 includes Auxiliar, Bradesco, BCN, Nordeste and Banerj.

Source: FFIEC 002 Reports.

The extent of the reliance on wholesale funding and engagement in recycling into international loans seems to have been a less prominent feature for the other Brazilian banks with a foreign presence. In the case of Banco Real, the second largest Brazilian bank in the US after Banespa and the first one to have set up business there in 1964, its borrowed money and interbank deposits accounted for about 38.9 per cent of their total US resources in mid 1982, and it had no liabilities to the federal fund markets. On the contrary, during the previous two years the bank had commonly been placing more liquidity in federal funds than it had borrowed from it, becoming therefore a net lender instead of taker of funds in the market.Footnote 24 Notably, liabilities to, and assets with, the head office and related institutions represented 41.8 and 20.4 per cent of the balance sheet respectively, meaning that the level of inter-office transactions was important and that a substantial portion of the resources came from internal sources. By that time, Banco Real had developed an extensive foreign banking network as part of its internationalisation strategy and was not only operating in the US and London but in many other countries as well. Rather than focusing on raising wholesale funding to fund sovereign loans, the international business of Banco Real included an important component of retail banking activity, especially in Latin America with 23 out of its 37 overseas banking offices scattered all over the region.Footnote 25 Banco Real, along with Banespa, accounted for the lion's share of the foreign banking offices of Brazilian banks, and as much as 53 and 90 per cent respectively of their assets and liabilities in the US and London.

The scale and scope of international financial intermediation was considerably more limited for the remaining 12 Brazilian banks that were operating overseas by mid 1982, and there were also important differences in the legal standing of their offices. Together they accounted for 47 per cent of Brazilian banking assets and liabilities in the US, with five of them, including large domestic actors like Bradesco and Banco do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (Banerj), arriving in the first half of 1982 and 1981, while most of the other banks had set up during the last years of the 1970s and 1980 (see Table 3). Notably, unlike Banespa and Mexican banks whose US offices had agency licences and could thereby only operate in the wholesale markets, many of these banks had branches, and this allowed them to take deposits from the public and engage in broader retail banking activities in the US. Banco Safra, for instance, had a branch in the US since 1973 with assets of US$181 million, and as much as 90 per cent of its funding base consisted of public deposits. For the group of banks that arrived in 1981–2, all of which had branch licence, total deposits accounted for about a quarter of aggregated liabilities, and only a quarter were interbank facilities with the balance also coming from the general public. On the other hand, for the group of banks that had settled up to 1980, of which four were agencies and two were branches, deposits from the public were virtually non-existent and interbank facilities such as borrowed money and federal funds had a more predominant role in the funding base. As in the case of Banco Real analysed above, internal funding appears also to have had an important role since liabilities to head offices and affiliated institutions accounted for as much as 28.8 per cent of the total and had no claims with them, a pattern also observed, although to a lesser extent, with the group of banks that arrived in 1981–2 (see Table 4). On the assets side, the loan portfolio accounted for as much as 70 per cent of the consolidated claims of these offices although there were considerable differences across banks. For Comind and Banco Safra, the third and fourth largest Brazilian banks in the US with similar volumes of assets, lending represented 25.6 and 87.5 per cent of their balance sheets respectively, while Bradesco had not yet granted credit, and the value for Banco Economico was 31.8 per cent, and as much as 93.8 per cent for Banco Itaú.

Although there is no systematic individual bank data on the UK offices of Mexican and Brazilian banks as in the US, archival records from the Bank of England indicate a similar pattern. A report on the role of foreign banks in London prepared by the Financial Statistics Division shows that at end-June 1982, Mexican banks’ obligations to the UK monetary sector and banks abroad reached US$2 billion or 77.5 per cent of total liabilities, while foreign currency lending to their parent country was US$1.5 billion or 60 per cent of the assets. However, the data for Brazilian banks, which is also provided at a consolidated level and includes Banco do Brasil, shows that UK and cross-border interbank obligations reached US$3.9 billion or 61.2 per cent of total liabilities and international loans to final borrowers in Brazil were US$1.5 billion or 23.7 per cent of their total assets.Footnote 26 These figures demonstrate that there was also a lower reliance by Brazilian banks on the interbank market as a source of funding in London when compared to their Mexican counterparts, but, most remarkably, the much lesser extent to which they were engaged in providing external lending back to their home country.

It seems, therefore, that the role of foreign agencies and branches as instruments for channelling foreign capital into the country, the salient feature of Mexican international banking, was much less prominent in Brazil. Figure 3 plots the ratio of international lending by the network of foreign offices of Brazilian banks under Resolution 63 and Law 4.131 to total Resolution 63 borrowing by the domestic banking sector between 1972 and 1982. It shows the extent to which international financial intermediation by the domestic banking system was largely conducted from Brazil under Resolution 63 rather than through the network of agencies and branches overseas. They grew from zero to 6 per cent in 1975, reached a peak of 16 per cent by 1979, but then fell during the following years despite the expansion of the foreign banking network. As opposed to Mexico, where a system of virtually fixed nominal foreign exchange rate between 1977 and 1982 could have led the banks to downplay currency risks when arbitraging between domestic and foreign markets, the regime of mini-devaluations and monetary correction in Brazil meant a continuous assessment of the upwards adjustments in the cost of external funding. An important additional difference was that while Resolution 63 operations benefited from some foreign exchange guarantees by the Brazilian central bank, the fundraising operations of the foreign offices were not covered by a similar scheme. Thus, although foreign offices could raise Eurocurrency liquidity at LIBOR or prime rate plus an interbank spread of 1/8–1/4 instead of the 1–2.5 per cent charged on cross-border Resolution 63 loans, it implied higher risk.

Figure 3. Share of Brazilian foreign offices lending to Brazil, 1972–82

Note: Ratio of Resolution 63 and Law 4.131 lending by the foreign network of Brazilian banks to total Resolution 63 borrowing (excludes the operations of Banco do Brasil foreign agencies).

Source: Based on data from Cruz (Reference Cruz1984) and Freitas (Reference Freitas1989).

IV

The outbreak of the international debt crisis of 1982 represented a major blow to foreign finance and international banking activities after years of growth and dizzying expansion. Mexico's announcement in August 1982 that it could neither roll over nor serve the principal on its bank loans, followed shortly by similar crises in Argentina in September, Brazil in November, and other major international debtor countries, spread the sovereign debt payment problems globally.Footnote 27 The scale and scope of defaults and reschedulings created significant tensions in the world capital markets that not only stopped the flow of syndicated and direct bank lending to the developing world (Cline Reference Cline1984), but also disrupted the underlying Eurocurrency wholesale and international interbank transactions (Guttentag and Herring Reference Guttentag, Herring, Ethier and Marston1985, Reference Guttentag and Herring1986). The uncollateralised nature and cumulative structure of this market made it vulnerable to shocks which could quickly push spread upwards and increase funding risks for some banks or group of banks (Saunders Reference Saunders, Portes and Swoboda1987). Indeed, during the Eurocurrency standing committee meetings in late 1982, BIS official Alexandre Lamfalussy reported to G10 central bankers that a ‘shrinkage of interbank positions and a halt in the cross-border interbank market’ along with ‘increasing tiering among banks and banking systems’ had been affecting the international money markets since the Mexican crisis.Footnote 28

The new international conjuncture and funding strains that unfolded in the global financial markets harmed the borrowing operations of financial and non-financial institutions from crisis countries. In Mexico, the network of agencies and branches of the six domestic banks that were operating abroad encountered major difficulties in securing their liquidity and solvency position, suffering indeed from a progressive withdrawal of interbank deposits throughout the last quarter of 1982 (Alvarez Reference Alvarez2018). Funding risk and the leakage of short-term wholesale credit lines was also an issue in the Brazilian case, but it was not a uniform and generalised problem as among Mexican banks and it mainly concerned Banco do Brasil. Archival records from the FRBNY and Brazil's international creditor banks show that Brazilian banks lost about US$3.5 to 4 billion in the interbank market in the second half of 1982, US$2.5 to 3 billion – or about three-quarters – of which was accounted for by Banco do Brasil's foreign agencies and branches.Footnote 29 As for the remaining quarter, it was largely concentrated on the foreign agencies and branches of Banespa, and, to a much lesser extent, the other 13 Brazilian banks overseas.Footnote 30

Figure 4 plots the evolution of the interbank deposits and money market liabilities of the US agencies and branches of Brazilian banks vis-à-vis their Mexican counterparts between 1982 and 1985. The chart makes clear that the most dramatic impact of the crisis was on the wholesale funding base of Mexican banks, which dropped by 25–30 per cent after the moratorium declaration of August 20 and continued at that level until the first quarter of 1983 when they started to recover as a result of the agreement subscribed to by creditor banks to maintain interbank deposits at pre-moratorium levels. Brazilian banks, by contrast, were still able to increase their wholesale funding base up to September, and then it declined by 11 per cent in the last quarter of 1982 (when the country went into crisis) and throughout the following year, accumulating a loss of 30 per cent by end-1983. Banespa and Banco Real were responsible for about two-thirds of this fall – 46.6 and 19.2 per cent respectively, with the balance shared by the other banks apart from Banco Auxiliar, Banco do Estado do Nordeste and Banco Safra for which wholesale interbank liabilities actually increased over this period. As in the Mexican case, an arrangement to restore interbank deposits at mid-1982 levels also started to be negotiated in late 1982, but agreement was only reached towards the end of 1983 to keep them at their current level.Footnote 31 Most notably, the outbreak of the crisis did not prevent new Brazilian banks from entering the US and successfully raising wholesale funding: Bamerindus and Bandeirantes opened their banking offices in the US during the very last quarter of 1982 and, along with Banco do Estado do Parana and Banco do Estado do Rio Grande which arrived later, were adept at accessing money markets and increasingly taking interbank deposits, as can be observed in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Interbank funding of Brazilian and Mexican banks in the US

Source: FFIEC 002 Reports.

The different extent to which the crisis affected the funding risk of Mexican and Brazilian banks is also evident in their balance sheets and wholesale market operations in London. Table 5 displays the net position of the London branches in the foreign currency business, and, in particular, the interbank net position as a percentage of total interbank liabilities by maturity band around the time of the outbreak of the crisis on 20 August 1982. The data show the significant shortening of the interbank funding base of Mexican banks with liabilities of less than three months, doubling from 30 to 59.8 per cent between August and mid November, as opposed to their Brazilian counterparts for which no major changes are observed. The relatively heavier concentration of net liabilities in the short term and net claims over the long term demonstrates the much faster degree of maturity transformation that had been performed by the Mexican branches, and its substantial increase in the immediate aftermath of the crisis. By contrast, the maturity structure of the Brazilian branches appeared not only less disturbed by the crisis but better matched beforehand, which would also indicate a lower involvement in funding long-term loans with short-term interbank credit lines, as in the case of Mexican banks.

Table 5. Maturity analysis of the London branches of Mexican and Brazilian banks, 1982

Sources: Task Force file 13A195/1; Bank of England archive.

The dire financial terms experienced by Mexican banks in the international wholesale markets was coupled with a relatively worse position for facing liquidity problems and securing the financial situation. On the one hand, although certainly important in both cases, the funding structure of the foreign agencies and branches of Mexican banks was relatively more heavily concentrated on interbank credit and money market facilities than that of Brazilian banks, as previously demonstrated. This meant, for instance, that unlike the branches of Brazilian banks with access to retail deposits in the US, the Mexican agencies were less well equipped to raise non-interbank dollar funding, thereby making their liquidity position more seriously vulnerable to shifts in this market. Importantly, none of the Brazilian or Mexican agencies or branches in London and the US had access to the discount windows of the Bank of England and the Fed respectively, and, with the exception of the New York branch of Banco Safra and Banco do Estado do Nordeste, they also did not benefit from Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) coverage. On the other hand, because of the higher degree of maturity transformation and larger involvement in sovereign lending, the capacity of Mexican banks to reduce their portfolios and adjust their balance sheet position was also more restricted, since these were long-term loans to borrowers in repayment difficulties or illiquid claims.

Indeed, the direct exposure of Mexican and Brazilian banks to the external debt payment problems of their home countries was also significantly different. By end-1982, outstanding syndicated or direct loans to the Mexican government or the private sector that were in the hands of foreign agencies and branches of Mexican banks reached US$4.27 billion, an amount representing over five times the capital base of the parent banks. In the case of Brazil, aggregated data from the central bank shows that external debt owed to Brazilian banks and Banco do Brasil reached US$7.8 billion at end-1982, of which US$6.9 billion or 88.7 per cent were Resolution 63 and Law 4.131 loans granted from the overseas offices with the balance essentially consisting of trade-finance facilities.Footnote 32 Although larger in absolute terms than the corresponding claims of their Mexican counterparts, relative to the capital base of their parent banks they represented about 76.3 per cent, a level almost seven times lower than in Mexico. In terms of assets however, foreign loans to Mexico accounted for about 15 per cent of the total assets of the banks, while the corresponding figure for Brazilian banks stood at 8.5 per cent. This shows the relative extent to which a potential default or serious debt payment disruption by Mexico and Brazil could undermine the solvency position of their major domestic banks and that the larger vulnerability of Mexican banks was related to poorer capitalisation levels vis-à-vis their counterparts in Brazil.

Along with the problems arising from the agencies and branches overseas, another source of potential vulnerability for Brazilian banks stemmed from the Resolution 63 operations that they had undertaken from their home offices. By end-1982, Brazilian banks’ currency loans under Resolution 63 accounted for about US$11.9 billion or 3.2 times the level of their interbank obligations (US$3.7 billion),Footnote 33 and the possibility of obtaining new credits or rolling over the current ones had virtually disappeared due to the disruption of international lending that followed the outbreak of the crisis. This, however, did not create the same liquidity pressures and funding risks that the retrenchment of the interbank wholesale market could potentially generate since they were not short-term obligations but had a much longer maturity structure as discussed in previous sections. Moreover, because the loans funded under the Resolution 63 scheme had shorter terms than the foreign obligations that originated them, the banks could reduce the portfolio and adjust the balance sheet to the retrenchment of international lending provided there was the availability of foreign exchange in the country to reimburse the creditor banks. Also, unlike the case of Mexican banks where the maturity mismatch of their external position became more deeply accentuated as sovereign loans began to be restructured at longer term while the interbank credit lines used to fund them remained short term, Resolution 63 obligations were folded into the rescheduling of Brazilian external debt. This meant that not only was their repayment extended, but also that the banks secured new loans as part of the negotiations and agreements subscribed to by the international financial community to manage the crisis.

The previous discussion shows that the way in which Brazilian banks engaged with international finance created considerably less vulnerabilities to the debt crisis and shifts in the world capital markets than for their Mexican counterparts. Yet not only had their foreign business been conducted through lower-risk borrowing and lending strategies and better care of the maturity structure, but they were also less leveraged on short-term external debt. In June 1982, the US$6–6.5 billion of interbank liabilities of the foreign agencies and branches of Mexican banks represented 5–5.4 times the capital base of the parent banks at an aggregate level and, although interbank deposits progressively fell, the ratio continued to increase over the rest of the year as the Mexican peso depreciated.Footnote 34 In the case of Brazilian banks, the US$3.7 billion of short-term interbank debt at end-1982 represented three-quarters of the consolidated capital base of the parent banks, although Banespa and Banco Real stood out with leverage levels higher than that but lower than the Mexican average as can be observed in Figure 5. Notably, the ratio of Resolution 63 debt to total capital is at or below 2 for most banks, which was the long-standing limit established by the central bank regulation before it increased to 4 in mid 1980. Banespa and Comind had leveraged the most on this instrument to finance the expansion of domestic lending, but this did not create the same kind of risks and vulnerabilities as did short-term interbank indebtedness. The systemic implications were also potentially more damaging in Mexico because the six banks in trouble represented up to three-quarters of domestic banking as of 1982, while their counterparts in Brazil were much less compromised and accounted for a market share of three-fifths.

Figure 5. Brazilian and Mexican banks' leverage on foreign funding

Note: Other (9) includes Bradesco, Banco Nacional, Unibanco, Nordeste, Bandeirantes, Banerj, BCN, Banco Safra y Banco Auxiliar.

Sources: Revista Bancária Brasileira, multiple bank bulletins and Lloyds Bank archive (book 9246).

V

This article has analysed the relationship between international banking, regulatory schemes, and financial fragility in Brazil and Mexico in the lead-up to the debt crisis of 1982, a topic that has been largely neglected in the literature to date. While in both countries the banking sector became increasingly involved with foreign finance, this study shows that the models of international financial intermediation that evolved out of the respective national capital mobility regimes and prudential supervisory frameworks were subject to different risks and vulnerabilities.

The contrasting ability of the Brazilian and Mexican banking systems to weather the crisis is a major finding. Rather than market structure and organisational characteristics of the banking industry such as concentration and bank size, this article argues that the explanation is to be found in capital controls and financial regulation. As a growing amount of literature has long discussed since the emerging market fallouts of the 1990s, open financial accounts and poor supervisory systems in developing countries are likely to increase banking fragility and result in full-fledged crises. With a more lightly normative institutional base for financial flows, Mexican banks developed a mechanism for channelling foreign capital to domestic borrowers that generated asset and liability mismatches that the more rigorous capital control and supervisory policies in Brazil aimed at preventing. Although interventionist approaches and heavy-handed administration may entail negative consequences for financial development and international banking integration, the Brazilian experience in the wake of modern financial globalisation suggests that that is not to be assumed and that the relationship could also go the other way. It also illustrates how capital control on inflows and prudential regulation may have benefits for mitigating risks and instability when facing financial crises.

Yet to what extent were these outcomes the result of deliberate policies – notably in the Brazilian case – or the by-product of two different historical approaches to capital flows? Unlike in Mexico where free convertibility and the absence of capital controls were long-standing polices, Brazil had a tradition of regulating cross-border financial transactions, and foreign exchange markets were subject to a variety of regimes and bureaucratic controls throughout the post-war period. To be sure, the framework established by Law 4.131 and Resolution 63 was at the base of the lower risks incurred by Brazilian banks when engaging with foreign finance, but this does not mean that the government and financial authorities were purposely looking to safeguard the position of the banking system. As it turned out, when the external financial position of the country deteriorated towards the end of the 1970s and early 1980s, prudential rules applicable to Resolution 63 operations were softened and other measures introduced that aimed to promote domestic banks abroad and supply the foreign exchange the country needed to deal with the balance of payment financing.Footnote 35 As for Mexico, after over two decades of relative macroeconomic and financial stability within an open and unregulated capital account regime during the so-called era of ‘stabilising development’, the involvement of domestic banks with international finance since the mid 1970s came to endanger the health of the banking sector and created vulnerabilities that brought the system to the brink of collapse in the wake of the 1982 crisis.

The fact that the Brazilian banking system proved more resilient than Mexico's raises the question of the implications for subsequent financial and economic development. How did bank financing and credit markets perform in both countries in the aftermath of the crises and what were the short- and long-term consequences for real outcomes such as economic growth and employment? Although a comprehensive analysis of these issues is well beyond the scope of this article, the stability of the banking sector in times of both crisis and non-crisis is always a presumably positive condition. In a context where the two governments had to deal with major international and domestic meltdowns, it is reasonable to believe that Brazilian policymakers had more manoeuvrability to cope with the crisis than their Mexican counterparts, who had to handle the situation of a banking sector under much more serious exposure. Moreover, to the extent that the stability of the Mexican banking system was more dependent on external financial support than was Brazil's, it is not too far-fetched to think that Brazilian negotiators were in a better position when negotiating austerity programmes and rescheduling agreements with their international creditors. However, confirming this hypothesis and whether this might have allowed Brazilians to obtain better deals and soften the burden of the adjustment to the crisis on the domestic economy are all aspects that require further investigation.

A final issue this article raises relates to the involvement of Banco do Brasil in international finance. Because of its peculiar double status as commercial bank and monetary authority, Banco do Brasil was a fundamentally different financial institution from the rest of the Brazilian banking sector and Mexican banks that constitute the focus of this study, and for that reason it has not been included in the comparative analysis. However, the fact that the volume of assets of Banco do Brasil in New York and London was significantly larger than that of the other Brazilian banks taken together and that its wholesale interbank credit lines were severely curtailed in the wake of the crisis are revealing findings. What was the nature of Banco do Brasil's engagement with the Euromarkets and where were all the dollars raised in the international money markets going? These are major concerns given that the bank in question was the main financial agent of the Federal government and held important central banking responsibilities such as the clearing of the domestic payment system, handling of the voluntary reserves of the banking system, and, most notably, interventions in the foreign exchange markets for managing the country's external imbalances and international reserves.