Introduction

In recent decades, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have been associated with negative health outcomes in early adolescence and adulthood (Boullier & Blair, Reference Boullier and Blair2018; Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards, Koss and Marks1998; Flaherty et al., Reference Flaherty, Thompson, Dubowitz, Harvey, English, Proctor and Runyan2013; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart, Mikton, Jones and Dunne2017). Further to the developmental impact of ACEs on children’s behavior and their social competence (Clarkson Freeman, Reference Clarkson Freeman2014; Manly et al., Reference Manly, Cicchetti and Barnett1994), a growing literature has found that the lived experience of ACEs can lead to long-term effects on the mental health of adults and the onset of chronic diseases (Boyce et al., Reference Boyce, Sokolowski and Robinson2012; Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Holden, Felitti and Anda2003; Sonu et al., Reference Sonu, Post and Feinglass2019).

In addiction research, child maltreatment and genetic factors have been linked to cigarette and marijuana use (Azimi & Connolly, Reference Azimi and Connolly2022), and ACEs have accounted for issues with illicit drug use in one-half to two-thirds of cases (Dube et al., Reference Dube, Felitti, Dong, Chapman, Giles and Anda2003). A modeling study showed that more than half of heroin and crack cocaine use was tied to ACEs (Bellis et al., Reference Bellis, Hughes, Leckenby, Perkins and Lowey2014). Another study by Hodgins et al. (Reference Hodgins, Schopflocher, el-Guebaly, Casey, Smith, Williams and Wood2010) tied the experience of childhood maltreatment to the likelihood of experiencing a gambling problem. Furthermore, ACEs have been associated with an increased likelihood of binge drinking among adults (Crouch et al., Reference Crouch, Radcliff, Strompolis and Wilson2018).

Substance craving is a core symptom of substance use disorders (SUDs), namely an uncontrolled desire which may be linked to one’s intentional use of substances, including self-regulation failure, diminished self-efficacy regarding substance abstinence, and affective response patterns (Sayette, Reference Sayette2016). Different models have relied on theoretical and empirical investigations involving in-depth explanations of craving and focusing on the autonomous reactions, or analyzing one’s biological imbalance and brain activity (Danese et al., Reference Danese, Moffitt, Harrington, Milne, Polanczyk, Pariante, Poulton and Caspi2009; Koban et al., Reference Koban, Wager and Kober2023; Skinner & Aubin, Reference Skinner and Aubin2010).

Hence, the appearance of craving can be linked to the severity of addiction, including the comorbid conditions and behaviors (Hormes, Reference Hormes2017). As Stalcup et al. (Reference Stalcup, Christian, Stalcup, Brown and Galloway2006) noted, the clinical management of craving requires four domains of analysis, namely environmental cues, stress-related conditions, mental impairment, and physical withdrawal.

In clinical terms, substance craving may persist over time in patients with SUDs, during either the progression or early remission of the disorder. The timeframe required for detecting an early remission of SUDs ranges from 3 to 12 months, although the symptoms of craving may still be present (Hasin et al., Reference Hasin, O’Brien, Auriacombe, Borges, Bucholz, Budney, Compton, Crowley, Ling, Petry, Schuckit and Grant2013).

Objectives

For this study, we investigated the role of ACEs on craving measures and collected clinical and patient-reported data from a sample of outpatients undertaking routine addiction treatment.

Methods

Sample and procedure

A sample of 208 outpatients ranging from 18 to 65 years old participated in this study. Participants were recruited between the period February and August of 2021 from five distinct addiction service centers that receive public funding from the Italian National Health System and offer free admission and healthcare services in the Salerno area, South Italy. All participants were administered questionnaires by trained psychologists as part of an individualized, routine clinical support plan for addiction and received no compensation for their participation. While the data collection and assessment were undergoing, a total of 125 patients were excluded from the study based on prior medical evaluations or by having already completed their treatment. A group of independent physicians supported the data collection, aiding in cross-referencing the information on diagnosis, comorbidity, and pharmacotherapy.

Measures

The Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) is a retrospective and self-reported measure of childhood adversities developed by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2018). A set of demographic information is followed by a total of 13 categories concerning adverse or stressful events during the first 18 years of one’s life.

The Substance Craving Questionnaire (SCQ-NOW) is a self-reported measure of craving that has been validated for substance use and gambling disorder, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.70 to 0.89 (Bonfiglio et al., Reference Bonfiglio, Renati, Agus and Penna2019). Adapted from the original version of a cocaine craving questionnaire by Tiffany et al. (Reference Tiffany, Singleton, Haertzen and Henningfield1993), it is composed of 45 items grouped into five dimensions. Each dimension is the sum of nine items, measuring the following factors: (1) desire to use a substance (DES); (2) intention to use a substance and preplanning (INT); (3) anticipation of positive outcomes (ANP); (4) anticipation of relief from substance withdrawal symptoms, or negative mood (ANR); (5) lack of control over substance use (LCO).

Data analysis

A preliminary data screening was performed to detect missing or invalid data. The patient characteristics were analyzed alongside the collected data from the subscales of the ACE-IQ and the SCQ-NOW. For analytical purposes, the mean and standard deviation of each continuous variable was noted, and the assumption of normality for each variable was examined by visual inspection and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

The cut-off score or mean value of the SCQ-NOW referred to the validation results as reported by Bonfiglio et al. (Reference Bonfiglio, Renati, Agus and Penna2019). The scores were presented as the average of the summed items and dichotomized. A score below the mean value on each subscale was referred to as “absent craving.” Conversely, a score equal to or above the mean value was referred to as “experienced craving.” Likewise, two dimensions of exposure, namely experience of childhood adversity vs. no experience of childhood adversity, were dichotomized from the ACE-IQ subscales.

Chi-square tests, Fisher’s exact method, and Spearman rank correlations were used to analyze categorical variables. A bivariate regression analysis was used to establish the strength of the association between the subscales of the SCQ-NOW and the ACE-IQ. The demographic characteristics and other clinical information were expressed by covariates and examined with the counts and percentages across the SCQ-NOW subscales and the ACE-IQ total score.

After adjusting for potential confounding variables, all variables with a p-value less than .05 were combined from the bivariate analysis and entered a multivariate logistic regression model (Kirkwood & Sterne, Reference Kirkwood and Sterne2010). The final model was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. Lastly, the adjusted odds ratios (aOR) were used to estimate the occurrence of experienced craving with a 95% confidence interval, given the exposure to at least one experience of childhood adversity.

Data analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics software, Version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and Jasp 0.15 (Jasp Team, 2020).

Results

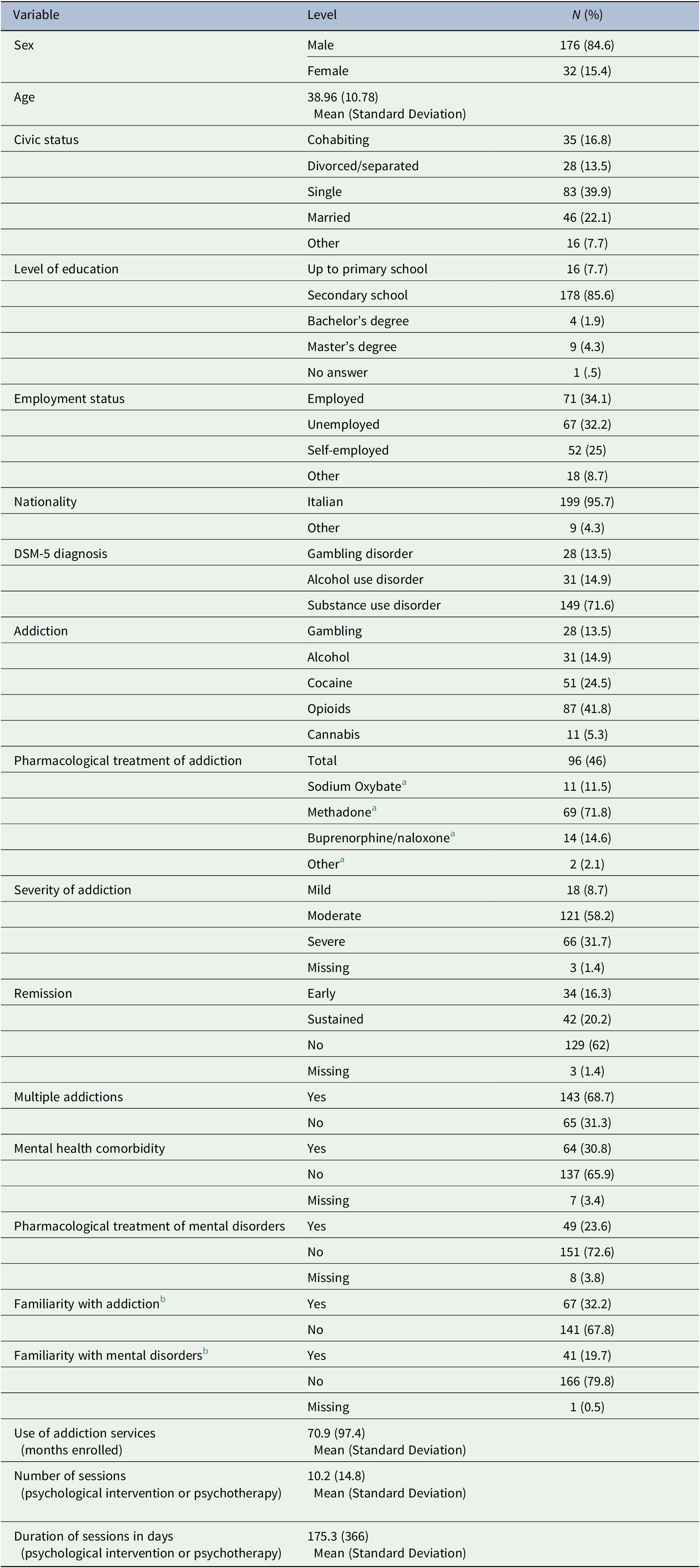

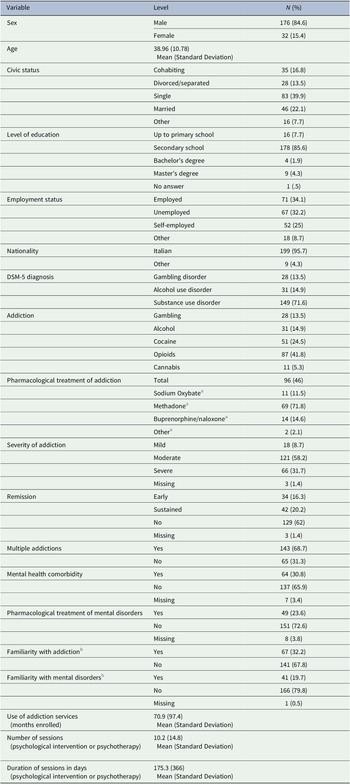

The patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics

Note. DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5).

a The percentage is calculated within the subgroup on pharmacological treatment of addiction.

b Familiarity equals clinical information or individual’s awareness of relatives/significant others with addiction or mental disorders.

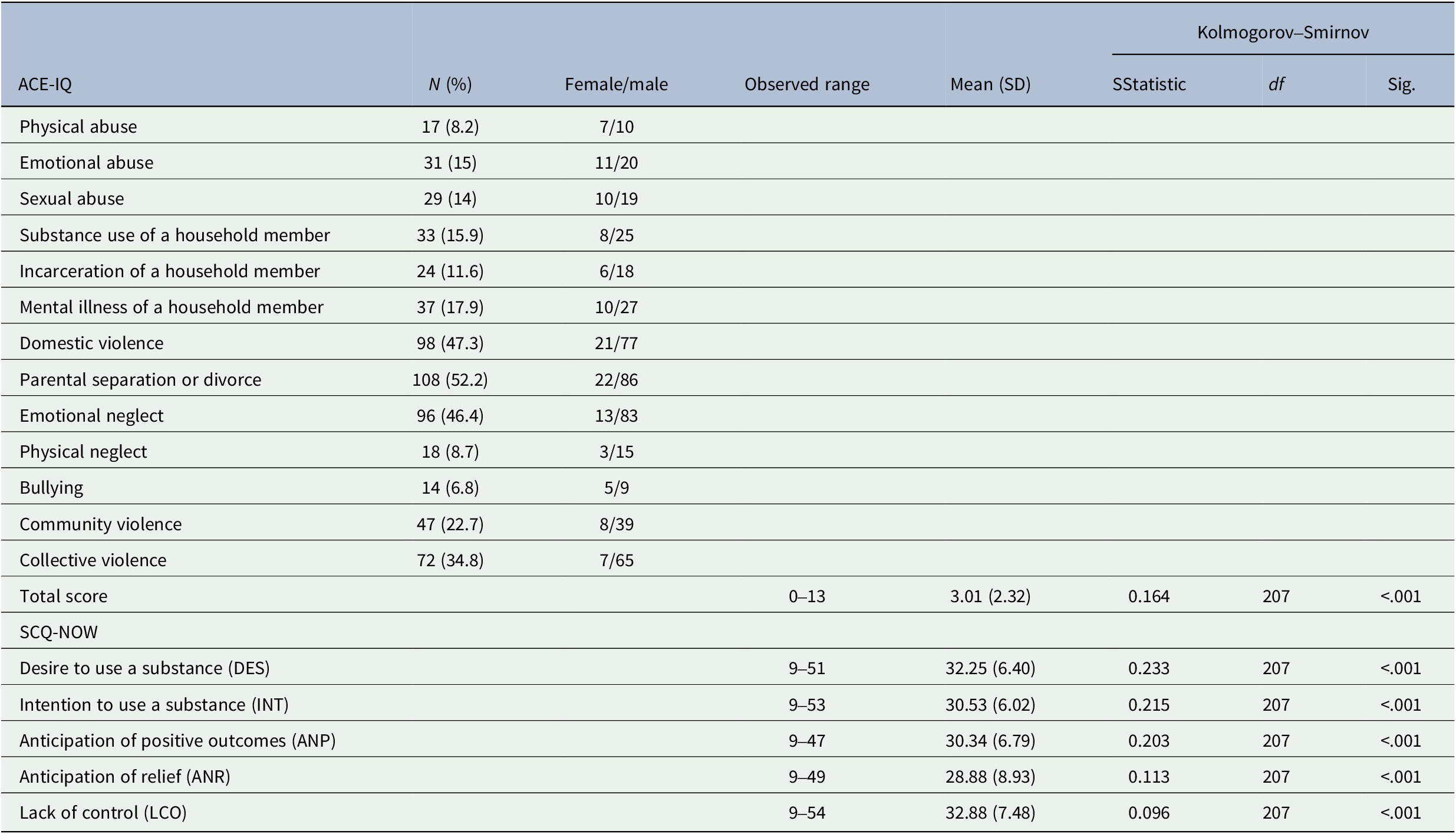

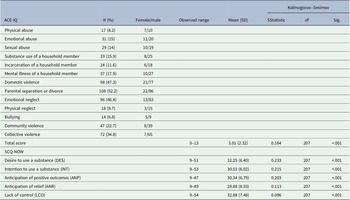

A consistent amount of exposure to ACEs and craving (89.1% and between 73.4 and 95.7%, respectively) was reported (Table 2).

Table 2. Observed range, mean and standard deviation (SD) for ACE-IQ and SCQ-NOW

Specifically, 56% of outpatients met the ANR threshold and presented no familiarity with mental disorders, while 57.2% reported ACEs and no familiarity with addiction. Among those reporting ACEs, 59.2% were not presenting comorbid mental disorders, including 20.4% of outpatients that were below the ANR threshold and 47.8% that were above it. The identification of this clinical subgroup indicated that when comorbid mental disorders were absent, ANR was more experienced.

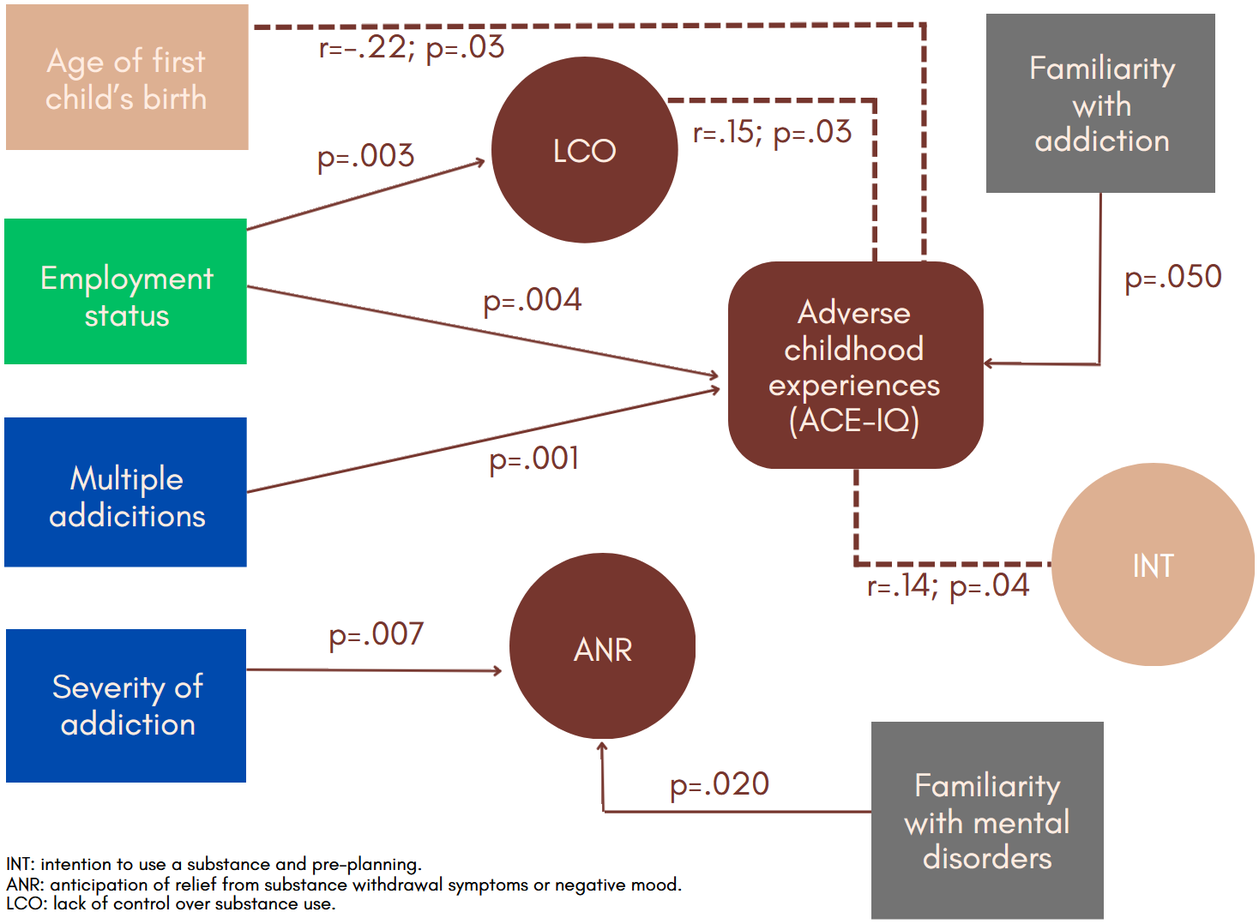

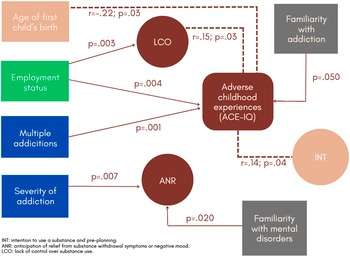

In Figure 1, statistically significant correlations between the ACE-IQ total score and the SCQ-NOW subscales are shown, including significant associations across the demographic and clinical characteristics.

Figure 1. Adverse childhood experience and craving

In terms of service use, significant negative correlations between either the number of sessions of psychological intervention or psychotherapy (r = −.23; p = .02) or the duration of psychological therapies in days (r = −.18; p = .017) and the ACE-IQ total score were found. Furthermore, statistically significant negative correlations were found between either the number of sessions of psychological intervention or psychotherapy (r = −.26; p = .001) or the duration of psychological therapies in days (r = −.27; p = .001) and the ANR subscale. A statistically significant negative correlation was also found between the number of months individuals were enrolled in addiction services and the ANR subscale score (r = −.20; p = .004).

The group of outpatients for which the severity of addiction was either moderate (aOR = 2.47; 95% CI: 0.89, 6.82) or severe (aOR = 5.05; 95% CI: 1.06 16.1) were, respectively, 2.47 and 5.05 times more likely to report high ANR scores compared to the group of outpatients with a low severity addiction. Additionally, the ANR score was 1.15 times higher for the group of outpatients reporting ACEs (aOR = 1.15; 95% CI: 0.98, 1.33). The final model (X2 = 13.03; p = .005) indicated a high sensitivity (.96) and low specificity (.11).

Discussion

Previous research evidence has suggested that the occurrence of childhood adversities is a potential source of toxic stress (Oral et al., Reference Oral, Ramirez, Coohey, Nakada, Walz, Kuntz, Benoit and Peek-Asa2016), in which stress reactivity (Groh et al., Reference Groh, Rhein, Roy, Gessner, Lichtinghagen, Heberlein, Hillemacher, Bleich, Walter and Frieling2020) and a prolonged state of exposure may trigger the toxic effects later in life (Shonkoff et al., Reference Shonkoff and Garner2012).

The ACE-IQ total score (Mean: 3.01; SD: 2.32) revealed distinctive features that were consistent with previous findings (Garland et al., Reference Garland, Reese, Bedford and Baker2019), as shown in the pioneering study of Felitti et al. (Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards, Koss and Marks1998).

In the present study, we found small and positive associations between either the LCO or the INT and the ACE-IQ total score, along with a small and negative association between the ACE-IQ total score and the age of first child’s birth. As a significant association between the ANR and the severity of addiction emerged, the results from the final model were collateral to previous evidence on the intergenerational transmission of behavioral risks resulting from ACEs (Schickedanz et al., Reference Schickedanz, Halfon, Sastry and Chung2018). Not surprisingly, a significant association between the familiarity with mental disorders and the ANR was also tied to the severity of addiction.

Following the recruitment of 208 study participants, we analyzed a larger population of outpatients in routine addiction treatment at different levels of morbidity, chronicity, and severity, even when the criteria for exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were not met. The main study limitation is that data analyses were performed on a limited sample with statistical significance that was determined at p < .05. Incidentally, we used retrospective estimates of ACEs which were tied to single self-reported measures of current craving. Therefore, the occurrence of overlapping physical or mental health issues will be a necessary step to validate our results with the ones from different socio-cultural settings and therapeutic contexts, as well as to benefit from the analysis of dissimilar measures for ACEs and craving at multiple points in time.

Conclusions

The main results extended the measures of craving in relation to the experience of ACEs and provided new evidence on cognitive, emotional, and automatic cravings in addiction (cf. Flaudias et al., Reference Flaudias, Heeren, Brousse and Maurage2019). Our pattern of analysis was consistent with the most recent findings from Romero-Sanchiz et al. (Reference Romero-Sanchiz, Mahu, Barrett, Salmon, Al-Hamdani, Swansburg and Stewart2022), in which urge and desire for cannabis were linked to craving following experimental exposure to trauma reminders. In particular, the duration of addiction treatment and the self-reported childhood adversities (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart, Mikton, Jones and Dunne2017; Kelly-Irving & Delpierre, Reference Kelly-Irving and Delpierre2019) contributed to explore the underlying mechanisms of ANR and more generally of psychological craving, compared to the self-medication attempts (Khantzian, Reference Khantzian1997), biological imbalance (Wise, Reference Wise1988), cue reactivity (Limbrick-Oldfield et al., Reference Limbrick-Oldfield, Mick, Cocks, McGonigle, Sharman, Goldstone, Stokes, Waldman, Erritzoe, Bowden-Jones, Nutt, Lingford-Hughes and Clark2017), and emotional states (Wilson, Reference Wilson2022). Drawing on findings from the craving literature, the lack of control or pre-planning, the intention to use substances, the occurrence of multiple addictions, a variable employment status, or familiarity with addiction were found significantly associated with the experience of childhood adversities.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/exp.2023.12.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request due to privacy or other restrictions.

Authorship contribution

Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Project administration, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing (C.R. and E.O.; equally contributed). Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing (N.S.B.). Conceptualization, Data Curation, Visualization (G.F., L.I., A.G., C.A, and A.N.; equally contributed). Data Curation, Project administration (G.C., B.L., G.T., and M.D.; equally contributed). Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft (M.P.P.). Visualization, Supervision (A.D.L.).

Funding statement

This work received partial financial support from the Campania regional plan for addiction prevention and recovery (grant number 86/2016).

Competing interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare that is relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical standard

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Comments

Comments to the Author: Thank you for addressing the requested changes. I am satisfied this has been completed.