1. Introduction

The terrorism threat level in Europe is critical [Reference Horton1, Reference Reardon2]. Terrorism is defined as the use of intentionally indiscriminate violence as a means to create terror, or fear, to achieve a political, religious or ideological aim [Reference Wieviorka3]. The concept of radicalisation differs, as there is a temporal dimension: it is a process that may lead to terrorist actions. For Khosrokhavar, radicalisation is a ‘process by which an individual or group adopts a violent form of action, directly linked to an extremist ideology with a social or religious political content that undermines the established political, social or cultural order’ [Reference Khosrokhavar4]. Beyond the repressive and security apparatus, many professionals and researchers from the fields of anthropology, political science, sociology, psychology and psychiatry have been involved in understanding terrorism and radicalisation.

Attempts to explain terrorism have explored the links among Islamism, the Muslim religion, delinquency and immigration. Sageman, a psychiatrist working for the Central Intelligence Agency, showed that terrorists are educated and mostly from the upper or middle classes [Reference Sageman5]. Several literature reviews have confirmed that there is no predefined pathway leading to radicalisation: radicalised individuals come from various backgrounds, have different origins, different family beliefs, social status or gender [Reference Fekih-Romdhane, Chennoufi and Cheour6–Reference McCauley, Leuprecht, Hataley, Winn and Biswas9]. The pyramidal model of radicalisation has been widely developed. This model emphasises the idea that only a few individuals would be likely to commit a violent act after undergoing a whole step-by-step process [Reference McCauley10–Reference Moyano and Trujillo14].

However, various authors have highlighted the difference between radicalised individuals who commit violent actions within a radical group (through a maturation process such as the pyramidal model) and individuals – the ‘lone wolves’- who act in a more isolated manner, who are radicalised more quickly and for whom the pyramidal model does not apply [7, Reference Zagury15, Reference Corner and Gill16]. The latter represent only a minority of the individuals involved in terrorist activities and are more likely to suffer from psychiatric pathologies [Reference Bénézech and Estano7]. Sageman reported no indicators of mental illness among the terrorists he studied [Reference Sageman5]. One may wonder why certain individuals are more likely than others to go through the different steps of the pyramidal model process of radicalisation. Some authors have put forward various predisposing factors, such as depressive tendencies or suicidal thoughts [17–Reference Victoroff19]. The feeling of injustice or humiliation has been also highlighted [Reference Victoroff, Quota, Adelman, Celinska, Stern, Wilcox and Sapolsky20]. Others insist on notions of identity and belonging, emphasising that being part of a radical group and embracing a cause gives a comforting sense of a ‘significance quest’ around a dedication that has an ‘empowerment effect’ for the radicalised individual [Reference McGilloway, Ghosh and Bhui8, Reference Mccauley and Scheckter21, Reference Kruglanski, Chen, Dechesne, Fishman and Orehek22]. Moments of ‘existential fragilities’ have also been mentioned as elements of vulnerability that can foster radical commitment [Reference Kruglanski, Bélanger, Gelfand, Gunaratna, Hettiarachchi, Reinares, Orehek, Sasota and Sharvit23]. Moghaddam noted the importance of the radical group effect, together with the major influence of leaders on the individual throughout the radicalisation process [Reference Moghaddam13]. Literature reviews suggest that the environmental, political, religious, social and cultural context plays an important role, making it difficult to compare the phenomenon of radicalisation from one context to another [Reference McGilloway, Ghosh and Bhui8, Reference Moyano and Trujillo14].

The studies mentioned above focus on terrorist movements of the 1990s (i.e., Al-Qaida [5, Reference Sageman22], terrorism in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict [Reference Merari, Diamant, Bibi, Broshi and Zakin17, Reference Victoroff, Quota, Adelman, Celinska, Stern, Wilcox and Sapolsky20]) in which terrorists target a foreign country or are fighting for national liberation. However, the understanding of terrorist acts has changed in recent years in Europe with the emergence of ‘homegrown’ terrorists, born and raised in Europe, who adopt the ideology of violent radical Islamism. The recruitment methods and the methods of action have changed and given rise to new models of radicalisation. Various political scientists, sociologists and governments have made this observation. According to Sageman, the increasing use of the Internet by jihadist movements since the 2000s has led to an organisational change: today’s radical groups are less organised and less centralised compared to previous hierarchical organisations such as Al-Qaida. Khosrokhavar also asserts that a new model of radicalisation has appeared in Western countries since the 2010s that is different from the pyramidal model. This new model has the following characteristics: the groups are smaller (three individuals, on average), more discrete (less proselytic), younger, and composed of more-fragile individuals who have been influenced by recruiters. Although the number of radicalised individuals remains marginal at the level of the general population, it has greatly increased since 2014 under the influence of Islamic State (IS) propaganda. In July 2014, the French Ministry of the Interior services listed 899 French people who either joined IS in Syria, returned from Syria, were on their way to Syria or said they wanted to join IS. An increase of 58% in six months was observed between January 2014 and July 2014 [Reference Ministère de24]. In August 2016, 364 minors were registered with the French judiciary authorities by the police because of objective and worrying signs evoking a radicalisation process [Reference Rapport Sénatorial25].

Existing literature reviews on radicalisation have mainly focused on adults and have scarcely explored the question of radicalised adolescents. However, since 2010, it appears that radicalised individuals in Europe are younger than they used to be (often teenagers) and that the number of young women involved is increasing [Reference Khosrokhavar4]. How do these young people shift from a symbolic affiliation with a European country to an organisation that was originally foreign to themselves and that advocates hatred and destruction of the environment in which they grew up? We formulate the hypothesis that there are similarities between the mechanisms at stake during the radicalisation process and the psychopathological manifestations of adolescence: the attraction towards an ideal place and the rejection of their symbolic affiliation could be reflected in the issues of separation and individuation that occur during adolescence and young adulthood.

In this systematic literature review, we focused on understanding the profiles of the European adolescents and young adults who have embraced the cause of radical Islamism since the beginning of the 2010s. Various organisations have observed that the profiles of the radicalised have changed since 2010 in Europe, and this new context deserves to be examined. We searched relevant data from medical and psychological search engines and obtained articles from various fields: psychological, sociological, educational, medical and anthropological. We chose to perform a multidisciplinary review, having noted in the scientific debates that each researcher tends to reduce the comprehension of this phenomenon towards his field of knowledge thus providing an incomplete panorama of the phenomenon. This broad approach aims to make a comprehensive inventory in order to return afterwards to a more specific psychiatric or psychological approach.

2. Methods

We performed a search in the PubMed, PsycINFO and Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection databases from January 2010 to July 2017. All papers containing the terms ‘Radicali*’ or ‘Terror*’ or ‘Violent Protest’ in the abstract AND ‘Adolescen*’ or ‘Juvenil*’ or ‘Teen*’ or ‘Youth’ or ‘Young People’ or ‘Young Person’ in the text were identified. Moreover, the French database from the MIVILUDES (Mission interministérielle de vigilance et de lutte contre les dérives sectaires for Inter-ministry mission of vigilance and fight against sectarian activities) was screened in order to identify relevant French articles on radicalisation. Because of its experience with sectarian hold, the MIVILUDES was one of the first governmental organisations commissioned to study radicalisation in France, and it played a pioneering role in this field of research.

For the selection of the relevant studies, we used the following criteria: (i) the study population included adolescents and/or young adults: subjects aged between 12 and 25 at the time of the radical engagement; (ii) the subjects lived in a Western European country: the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence showed that the majority of the youth who left for Syria and Irak since 2013 came from Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Netherlands or Great-Britain [26] (iii) the study was about radicalisation at large; (iv) the study included empirical data and not only theoretical information or views; (v) the study was recent (2010–2017). The PRISMA diagram flow (Fig. 1) maps out the number of records identified, included and excluded, and the reasons for exclusion through the different phases of the selection process. Of the selected studies, two co-authors (NC and AO) selected the relevant information independently: authors (year), study design, the number of individuals, age ranges, gender distribution, country, radicalism criteria, features of the sample, assessment tools used in the studies, and the main findings.

Fig 1. The PRISMA diagram flow of the literature review.

3. Results

In total, we found 22 publications. Their main characteristics are summarised in Table 1. As expected, they came from different fields (e.g., sociology, anthropology, psychology, medecine) and used different methodologies (e.g., qualitative, quantitative). Among the 22 articles, 20 were about radicalisation related with Islam. The two remaining articles concerned affiliation to an extremist ideology or extremist group without any religious specificity or any link with Islam. Regarding the sample of interest, Table 1 distinguishes studies focusing on terrorists or individuals involved in violent actions (n = 4), studies focusing on individuals who intend to join the Islamic State or present extremist ideology (n = 5), studies focusing on adherence to radicalisation in general population samples (n = 7), and studies focusing on theoretical aspects based on single case reports or small series (n = 6). To obtain a broad view of the complex phenomenon of radicalisation, we decided to present the main results of this review according to 4 axes: (1) the different classifications that have been proposed to delineate radicalised individuals; (2) the individual risk factors of radicalisation; (3) the micro-environmental risk factors of radicalisation; and (4) the societal and cultural risk factors of radicalisation.

Table 1 Characteristics of the studies included in the review.

EU: European Union; Fra: France; Ger: Germany; Ned: Netherlands; Spa: Spain; UK: United Kingdom; IS: Islamic State.

3.1 Existing categorisations and typologies

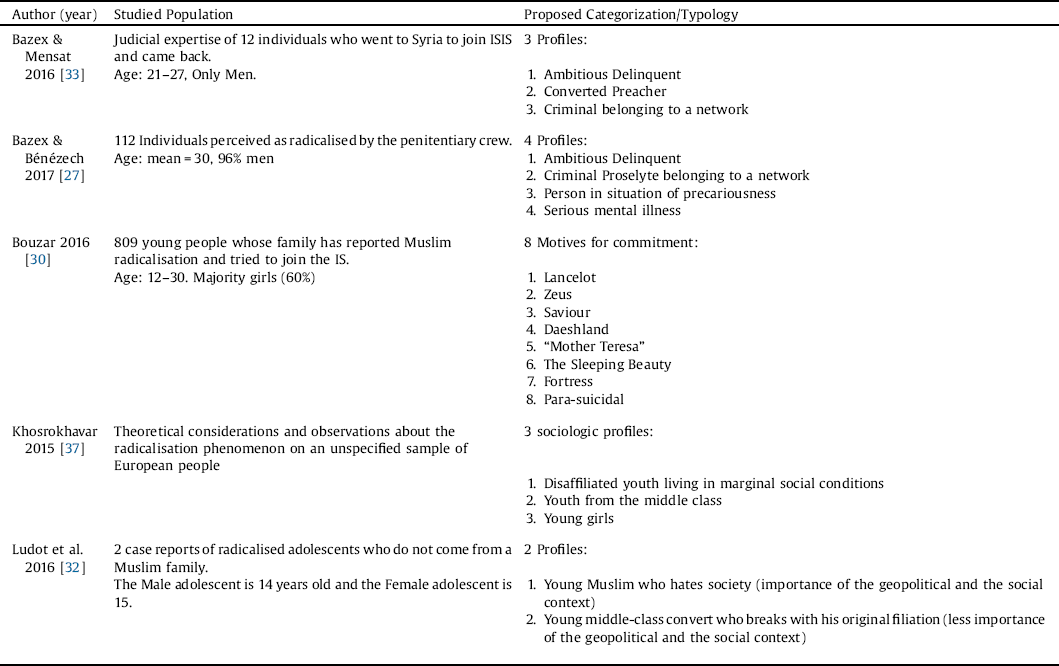

Various authors have suggested categorisations of different forms of radicalisation trying to decipher the phenomenon and to identify subgroups or profiles of interests within radicalised youths. These different categorisations are presented in Table 2. These categorisations are not comparable, because of the great variability of methodologies, approaches (criminological, sociological, anthropological) and populations from which they are developed. However, they portray the complexity of the profiles of these radicalised individuals. To detail one example: the usual categorisation used by law specialists to described terrorists, which distinguishes mainly 2 profiles (lone actor terrorist vs. group-based terrorist [Reference Corner and Gill16]), does not seem to fit radicalised young Europeans seen in prison contexts, where 3–4 profiles are proposed (see Table 2). Generally, these categorisations do not allow any correspondence with current classifications of mental conditions (e.g. DSM-5).

Table 2 Existing categorizations and typologies for radicalised youth.

3.2 Individual risk factors

Psychiatric disorders are rare among radicalised youths. Individuals with a psychiatric condition represent a minority of the individuals involved in terrorist activities. Bazex and Bénézech found that only 10% of the individuals under the hand of justice for radicalisation presented a psychiatric disorder [Reference Bazex, Bénézech and Mensat27]. Besides, the average age of these individuals with psychiatric disorders is the highest (34 years) among the 4 categories proposed (see Table 2, [Reference Bazex, Bénézech and Mensat27]). For the rest of the individuals, they note various personality traits without a formal psychiatric diagnosis: anti-social, obsessional, and histrionic traits (especially in proselytic behaviours). Rolling corroborates this finding: she reports only 3 individuals with mental disorders among the 25 included in her study [Reference Rolling and Corduan28], knowing that this study is based on a young population (13–20 years) received in child psychiatry and not necessarily known to justice for radicalisation.

In contrast, several authors describe trait vulnerabilities or psychological vulnerabilities. Several types of psychological vulnerabilities have been highlighted as risk factors for youth radicalisation. A depressive dimension is often reported among radicalised youth, with a frequent feeling of despair that does not qualify as a major depressive episode (although formal psychiatric diagnosis is not available in most studies). Radical commitment can be thought of as a way to fight against this depressivity [Reference Rolling and Corduan28, Reference Benslama29]. For Benslama, the power of jihadist attraction comes from the ‘exalting promise’ that offers the adolescent a ‘soothing of the pain of living’ [Reference Benslama29]. Several authors hypothesise that radical ideology could often hide a suicidal intentionality. The notion of martyrdom is attractive because it gives meaning to one’s existing fragilities and suicidality. The issue of suicidal intentionality remains complex. While some authors insist that the promise of a ‘true’ life in the hereafter gives to death a saving status [Reference Khosrokhavar4, Reference Benslama29], others evoke pre-existing suicidal intentionality for certain subjects [Reference Bouzar and Martin30]. The relationship to death probably varies from one subject to another and is somehow reflected in the radical ideology that gives death a central place. This echoes Durkheim’s notion of ‘altruistic suicide’ by excess of integration [Reference Durkheim31]. In total, we lack empirical evidence to address the issue of suicidal intentionality among radicalised youths.

A history of addictive behaviour is often reported. Dependence on the radical group may act as a substitute product and replace the previous addiction: some subjects reported that the positive and rewarding effect of religious commitment allowed them to get rid of an addiction to a substance [Reference Bénézech and Estano7, Reference Ludot, Radjack and Moro32]. Radical commitment can also be conceptualised as a risky behaviour, with all the appeal it has for teenagers. For radicalised youths, going to Syria represents an initiatory quest [Reference Khosrokhavar4, Reference Bazex and Mensat33]. Addictive behaviour, risky behaviour and sensation seeking attitudes are common conduct disorders found among delinquent adolescents [Reference Thornton, Frick, Ray, Wall Myers, Steinberg and Cauffman34]. Radical commitment channels these behaviours by giving to the subject a firm framework within the group. Finally, early experiences of abandonment are found in most of the radicalised youth’s life trajectories [Reference Bazex and Mensat33]. A perceived fragile family structure and painful parental representations are vulnerability factors for youth radicalisation [Reference Rolling and Corduan28, Reference Bazex and Mensat33].

Adolescence per se is a risk factor for radicalisation. Adolescence is a phase of turbulence and reorganisation. For some adolescents, the inherent detachment from primary care givers and finding one's own identity bring a loss of security and sometimes a fear of loneliness and of being abandoned [Reference Rolling and Corduan28, Reference Ludot, Radjack and Moro32]. Belonging to a radical community conveys a sense of belonging, a sense of meaning and comfort [Reference Dhami and Murray35]. Based on the psychoanalysis of a radicalised subject and the content of jihadist propaganda, Leuzinger-Bohleber claims that the IS permits the satisfaction of pre-genital drives, which are rekindled in the early phases of adolescence [Reference Leuzinger-Bohleber36]. Violent actions advocated by radical groups unconsciously offer an enormous satisfaction of archaic drive-impulses and can be experienced as an omnipotent victory over the fear of death [Reference Leuzinger-Bohleber36]. Also, finding love objects outside of the family is another major issue of adolescence and is simplified by the organisation, which guarantees a reassuring marriage [Reference Leuzinger-Bohleber36]. Motivation towards marriage is found more frequently in young girls than in young men who are generally more attracted by the fascination exerted on them by armed combat [Reference Bouzar and Martin30, 37]. The changes in identifications during adolescence and the quest for an ideal open the way to radical ideologies [Reference Ludot, Radjack and Moro32]. Thus, the message sent by the IS may become attractive for some adolescents. The adolescent characteristics of the radicalisation process had not been put forward in the terrorist movements of the 1990s and 2000s. Bazex and Bénézech showed an age effect on the reason of justice control: subjects under judicial control for acts of apology or for acts of terrorism are much younger than those condemned for ordinary law crimes. On one hand, there are young people for whom radical engagement leads them to be under judicial control, and on the other side there are condemned adults who meet, by availability, radicalisation in prison. Individuals in prison can encounter radical commitment in a very variable way [Reference Bazex, Bénézech and Mensat27].

Personal uncertainty is another individual risk factor for radicalisation. Identity and identification issues and idealisation processes are central during adolescence. For several authors, these issues are at the core of the radicalisation process. The neo-identity associated with the radical group and ideology may give a new and reassuring meaning to the young person's experience [Reference Ludot, Radjack and Moro32]. Some add a dimension of imaginary affiliation to fallen Muslim origins that the subject glorifies again through his/her commitment [Reference Benslama29]. Radicalisation is viewed as an ‘act of recovery of identity’ or ‘recovery of lost dignity’ [Reference Khosrokhavar37]. Members identify with the leader’s power and prestige which compensate for the failures of their individual narcissism [Reference Bénézech and Estano7]. Theories of narcissism and grandiosity in groups highlighted the fact that the figure of the leader and the ideology becomes for the members of the group their ego ideal [Reference Kaës38]. This mechanism acts as a megalomaniac protection against anguish that reinforces the subjects’ fantasies of immortality [Reference Kaës38]. Middle-class youths can also experience this feeling of ‘victimisation’ by suffering from anonymity and non-belongingness. The latter could therefore also engage in jihadism because of a lack of identity firmly anchored in reality. The fact that adolescents from middle class and without family affiliation with Islam undergo radicalisation process underlines the importance of the adolescence process in this choice of radical engagement [Reference Ludot, Radjack and Moro32]. For Doosje, personal uncertainty is one of the three main determinants of a radical belief system, along with perceived injustice and perceived intergroup threat [Reference Doosje, Loseman and van den Bos39]. This finding is based on Hogg's ‘uncertainty-identity’ theory: the more individuals are uncertain in their environment, the more likely they are to identify themselves massively with groups [Reference Hogg40], and the more the properties of this group form a unit where individuals seem interchangeable, the more effectively this group reduces uncertainty [Reference Hogg, Meehan and Farquharson41].

Perceived injustice, or the feeling of injustice, is another determinant of radicalisation. It is cited in several studies, whatever the vocabulary or the methodology used: ‘Perceived injustice’ [Reference Doosje, Loseman and van den Bos39], ‘Perceived Oppression’ [Reference Moyano and Trujillo14], ‘Frustration’ [Reference Bazex, Bénézech and Mensat27], ‘Despair’, ‘Sense of Unworthiness' or ‘Perceived contempt’ [Reference Khosrokhavar37]. All these terms illustrate a deep malaise of the subject who tries to give sense to this ‘existential failure’. This ‘injustice’ is often put forward by the radicals themselves to justify their commitment and designate the culprits. Benslama also explains that this feeling of injustice, often provoked by personal experience, is then covered by radical ideology, giving a stronger value to its commitment [Reference Benslama29]. The link between perceived injustice and the reality of a socio-economic discrimination is developed below (see macro-envionnemental risk factors).

Several authors state the importance of a triggering event as a determining factor in acting out or at least reinforcing the radical commitment. The list of events includes the occurrence of a brutal trauma concerning a loved one (e.g., bereavement, illness, separation) [Reference Bouzar and Martin30, Reference Schuurman and Horgan42]; the occurrence of a love disappointment [Reference Bazex and Mensat33]; the viewing of a video of a battered woman who reminded him of his mother [Reference Schuurman and Horgan42]; or the viewing of a video that reactivated a profound suffering linked to family history [Reference Bazex and Mensat33]; and a recent experience of discrimination or the diffusion of violent and unsustainable videos [Reference Bouzar and Martin30].

Finally, several authors have described psychopathological mechanisms that are at stake during radicalisation and that reinforce radical engagement. The idea here is to explain the psychological mechanisms involved once the individual has started the process of radicalisation. First, projection is active: radical ideology offers the subject the possibility to project onto his enemies all the evil he feels inside and to soothe his guilt by what is designated as an act of purification [Reference Dayan43]. This operation may be accompanied by a paranoia mechanism and a use of splitting of the ego. This paranoia mechanism acts as a defense mechanism and does not account for a psychiatric pathology or personality organisation [Reference Bénézech and Estano7, Reference Bazex, Bénézech and Mensat27, Reference Benslama29]. The splitting process is highlighted by several authors and explains how these individuals can set aside the moral values they had in the past [Reference Zagury15, Reference Bouzar and Martin30, Reference Dayan43]. Various authors have reported that obsessive compulsive habits are also frequent among radicalised youth [29, Reference Bouzar and Martin30]. These symptoms often have a function of ‘purification’, such as found in radical ideology or the practice of a rigorist religion. Radical engagement may soothe pre-existing anxiety symptoms by offering a reassuring framework. For Khosrokhavar and Ludot, today’s European jihadists of the middle classes suffer from a lack of authority and are in need of an authoritarian normativity that shows them rules to follow [Reference Ludot, Radjack and Moro32, Reference Khosrokhavar37]. These elements show the importance of the radical group that welcomes the candidates to radicalisation, and they suggest how the influence of the micro-environment is decisive in the process of radicalisation.

3.3 Micro-environmental risk factors (family and proximal environment)

Fragility and failure of the family group is a risk factor for radicalisation. Studies focusing on the families of radicalised youths often portray deficiencies, traumas and/or distress during the childhood and adolescence of these subjects [4, Reference Rolling and Corduan28, Reference Bazex and Mensat33]. In Bazex and Bénézech’s study, which included 112 individuals under judicial control for radicalisation, they report a large proportion of individuals who experienced ‘a childhood marked by significant parental difficulties, a father often absent and a mother whose integrity is often attacked (depression, suicide attempt, disability)’ [Reference Bazex, Bénézech and Mensat27]. In their view, this contributes to a major inconsistency in identificatory processes (in other words, identity uncertainty). Among the members of the Hofstadgroup, a Dutch terrorist organisation, Schuurman found that one of the risk factors that makes the radical group particularly effective is the isolation of the subject and the absence of countervailing opinions in the family [Reference Schuurman and Horgan42]. The lack of a corrective answer to the subject’s radical positions was also reported by Van San et al among 16 Islamists and extreme right adolescents who exposed on the internet their radical ideas [Reference Van San, Sieckelinck and de Winter44]. He described permissive parents with little response to their child's radical opinions.

Friendship or admiration towards a member of the radical group is often reported. This seems obvious in studies focusing on the most-extremist cases seen in judicial contexts. Most of the radicalised individuals had a role model, an inspirational figure in the radical group who initiated the process of radicalisation. Schuurman highlighted this finding for individuals among the ‘Hofstadgroup’ in Holland, and Bazex confirmed it among French radicalised youths returning from Syria [Reference Bazex and Mensat33, Reference Schuurman and Horgan42].

Several authors have found similarities between the techniques of radical jihadist groups and sectarian community methods to recruit new members. Based on his knowledge of sectarian methods, Dayan described common mechanisms such as narcissistic gratification, moral debt, real or imagined threats and the progressive setting aside of the family/friendship network [Reference Dayan43]. Rolling described two phases in the radicalisation process of the youth encountered in child psychiatry units: a first phase during which the radical commitment has a soothing function on psychic suffering and a second phase during which the ideological indoctrination leads to the self-effacement of the subject in favour of the group [Reference Rolling and Corduan28]. Bouzar studied the way the youth was enlisted on the internet and explained that the ‘recruiters’ of radical groups adapt the propaganda media to the ‘sensitivity’ of each subject [30, Reference Bouzar45]. Youths are subject to psychological pressure from the recruiters to adopt the radical beliefs and to break with friends and family [Reference Bouzar46]. Bazex & Bénézech highlighted one category of radicalised individuals who have a charismatic character associated with proselytic and manipulative behaviours: ‘the proselytic networker’ [Reference Bazex, Bénézech and Mensat27]. Radicalised individuals with other profiles (e.g., ‘ambitious offenders’; ‘people in a precarious situation’) may be vulnerable to indoctrination by ‘proselytic networkers’. Khosrokhavar also reported this form of relational dissymmetry between a charismatic individual who exerts an influence on more-fragile individuals [Reference Khosrokhavar4].

The radical group instigates the subject’s dehumanisation. This is a key process to understanding how mainly normal individuals can engage in terror activities. For Bazex & Bénézech, the radical group and ideology help to legitimise a pre-existing violence in the subject [Reference Bazex, Bénézech and Mensat27]. The aggressive and destructive instincts that dominate the fantasy life of these individuals find a way of justification and ideal expression in projection towards the outside. Dayan states that there is a ‘narcissistic contract’ between the individual and the group and that this contract is crucial: the group offers a place and a role to the subject, and in exchange, he must repeat the same statements and ensure the permanence of this transmission [Reference Dayan43]. Khosrokhavar studied the case of young Europeans who wanted to go to Syria [Reference Khosrokhavar4]. He explained that this desire was more often driven by humanitarian concerns than by violent radicalism. He described these young people as ‘pre-radicalised’ and explained that once within the group, they learn to become insensitive to the suffering of others and becoming ‘real jihadists’. Bouzar identifies four steps used by recruiters in order to effect the ‘dehumanisation’ of the subjects: (i) isolation of the individual from his environment; (ii) destruction of the individual as a unique personality for the benefit of the group; (iii) adherence to the IS ideology; (iv) dehumanisation of the subject and of his future victims [Reference Bouzar46]. These steps are consistent with Bandura's work on ‘moral agency’ and dehumanisation: ‘The moral disengagement may center on the cognitive restructuring of inhumane conduct into a benign or worthy one by moral justification, sanitising language, and advantageous comparison; disavowal of a sense of personal agency by diffusion or displacement of responsibility; disregarding or minimising the injurious effects of one's actions; and attribution of blame to, and dehumanisation of, those who are victimised’ [Reference Bandura47]. These mechanisms are also described by Zagury [Reference Zagury15] and Bouzar [Reference Bouzar46] when they explore the link between the ‘recruiters’ and the youth exposed to radical theories.

3.4 Macro-environmental risk factors (cultural and societal environment)

The evidence of macro-environmental factors is more complex. Social polarisation is one such risk factor. Unequal or discriminatory socio-economic conditions are highlighted by many authors as contributing to the phenomenon of radicalisation. Khosrokhavar explains that the ‘ghettoized existences’ associated with the sense of dehumanisation subjects feel through social disregard lead them to the desperate conviction of being in a deadlock [Reference Khosrokhavar4]. When this conviction is not associated with an ideology, these young people may take the path of delinquency. If this conviction finds religious ideological support, the hatred of society is sacralised and the goal becomes to ‘save Islam’. Khosrokhavar noted that most French people who have committed terrorist acts were born in disorganised families, had grievances against society, had a feeling of social injustice and a denial of identity (feeling neither French nor from their country of origin) [Reference Khosrokhavar4]. Moyano studied Muslim and Christian high school students in Spain and showed a significant polarisation between the two groups when they came from the same neighbourhood [Reference Moyano and Trujillo14]. When asked what defines them best, Muslims mostly chose identification with religion (when they could choose Spain or their country of origin), while Christians chose their country. Similarly, French authors reported that young people who have returned from Syria or young people under the grip of justice for radicalisation often had difficulties in social integration, particularly at school, with a history of exclusion [Reference Bazex, Bénézech and Mensat27, Reference Bazex and Mensat33].

Doosje et al identified perceived group threat as a major contributor to maintaining a radical belief system [Reference Doosje, Loseman and van den Bos39]. The perceived group threat may take three different forms: symbolic threat, realistic threat, and intergroup anxiety. Symbolic threat refers to threat to the Islamic culture. Realistic threat refers to threat to the economic status of one’s group. Intergroup anxiety is defined as the fear one can experience when one has to interact with a person from another group. Once again, these results underline the importance of group polarisation and its consequences for feelings of oppression or perceived injustice. Bhui supports the use of a public health approach to understand and prevent violent radicalisation, arguing that anti-terrorism approaches based on the judicial system or on criminology do not prevent radicalisation, since they intervene after the act [Reference Bhui, Hicks, Lashley and Jones48]. These latter actions would even tend to stigmatise Muslim communities and undermine social cohesion, while better social cohesion is associated with a reduction of violence, better public health, and a more equal and just society. To support this view, Bhui et al. studied vulnerability factors and resistance factors to violent radicalisation in a cross-sectional survey of a representative population sample of men and women aged 18–45 of Muslim heritage in two English cities [Reference Bhui, Warfa and Jones49, Reference Bhui, Everitt and Jones50]. They showed that sympathy for violent protest and terrorist acts was more likely to be articulated by those under 20, by those in full time education rather than employment, by those born in the UK, by those speaking English at home, and by high earners (>£75,000 a year). Anxiety and depressive symptoms, adverse life events and socio-political attitudes showed no associations. On the other hand, resistance to radicalisation measured by condemnation of violent protest and terrorism was associated with a larger number of social contacts, less social capital, unavailability for work due to housekeeping or disability, and not being born in the UK [Reference Bhui, Warfa and Jones49, Reference Bhui, Everitt and Jones50]. Interestingly, here again, sympathy was higher among the youngest individuals and those born in the UK rather than immigrants [Reference Bhui, Warfa and Jones49, Reference Bhui, Everitt and Jones50]. In another cross-sectional study in the UK, Coid et al showed that men at risk of depression may experience protection from strong cultural or religious identity [Reference Coid, Bhui, MacManus, Kallis, Bebbington and Ullrich51]. These results seem paradoxical and highlight the importance of a consideration at all three levels (macro, micro and individual): some factors can act either on the side of protection or of vulnerability to a radical system.

The link between religious fundamentalism and radicalisation is complex. Many authors mention the importance of religion in the process of radicalisation. Moyano reported that Muslim religious identity was stronger than Christian identity in Spain [Reference Moyano and Trujillo14]. Dayan noted recent claims of religious identity among French youths [Reference Dayan43]. Coid showed that religious affiliation and practice were protective against antisocial behaviours but could determine targets of violence following radicalisation [Reference Coid, Bhui, MacManus, Kallis, Bebbington and Ullrich51]. Benslama emphasised the importance of the history of the Arab world and Islam in explaining the discourses of Islamic fundamentalists and the creation of a new identity figure that he called the ‘super-Muslim’ [Reference Benslama29]. According to Benslama, there is a ‘constraint under which a Muslim is led to outbid the Muslim he is by the representation of a Muslim who must be even more Muslim’. The subject is encouraged to identify himself with ‘the perfect Muslim, the Prophet and the ancestor’, according to the belief that ‘the good has already happened, the promise has been fulfilled, there is nothing left to do but to return to the past, while waiting for the end of the world, or better: to hasten it’ [Reference Benslama29]. Benslama illustrates how religious fundamentalism provides an identity figure in which youths can find a totalising meaning. It is crucial to differentiate Muslim religion from radical Islamist ideology. Some political scientists have argued that for ISIS, religion is more a way to justify their actions, rather than a cause to defend, unlike other forms of religious fundamentalism [Reference Roy52].

The geopolitical context also has a major influence. Several authors have noted that the proclamation of a caliphate by the IS added legitimacy to this radical ideology [Reference Khosrokhavar4, Reference Benslama29, Reference Bouzar and Martin30]. Contrary to the Al-Qaeda network, the IS is anchored in a territory, and its propaganda describes the territory as an idyllic place, a community utopia where the Muslim ‘brothers’ are most welcome. Different terms have emerged, conveying the message of ideological propaganda associated with this territory: the ‘Hijra’ (emigration of a Muslim from a non-Muslim country to a Muslim country), the ‘Land of Al-Sham’ (literally ‘land on the left-hand’, referring to a Caliphate province in the region of Syria) or ‘Ummah’ (world community of Muslims). Geopolitical events undoubtedly influence the phenomenon of radicalisation whether in its rise in 2014 during the proclamation of the caliphate or during its decrease in intensity since the IS was defeated in Syria and Iraq in 2017.

Societal changes may affect the radicalisation process. According to various authors, the mutations of modern societies may favour the appearance of the phenomenon of radicalisation. Khosrokhavar uses Durkheim's term ‘Anomie’ [Reference Durkheim53] to explain that the dissolution of the moral, religious or civic values of modern societies leads to a feeling of irresolution that makes youths more inclined to turn towards religious fundamentalisms and possibly towards radical ideologies [Reference Khosrokhavar4]. These considerations are in line with Zygmunt Bauman's more modern concept of ‘liquid modernity’, according to which the individual is integrated only by his act of consumption [Reference Bauman54]. Social status, identity or success are defined in terms of individual choices and can fluctuate rapidly depending on socio-economic requirements. This fluid modernity brings at the same time freedom but also uncertainty and insecurity. Khosrokhavar [Reference Khosrokhavar37] adds that among these young people, who suffer from the ‘deliquescence of politics’ and the ‘dispersion of authority between several parental bodies’, radical Islamism offers tangible and reassuring norms carried by an unequivocal authority. Benslama also discusses this change in the social model [Reference Benslama29]. He explains that the traditional model, in which filiation defines the identity of the subject, is endangered in favour of a new social model where each subject needs to forge his own place and identity, with all the anxiety it can generate. Some individuals have the resources to face this challenge, but those who fail to do so may be tempted by the solutions offered by the radical ideologies by attacking the society that has placed them in this insecure situation. Radicalised individuals believe that radical ideology, by destroying the existing society, offers them the possibility of a promising new societal model. Also, the society is believed to convey all kinds of conspiracies by forces that stole power from the people (e.g., financial power), and IS recruiters use conspiracy theories to destroy the world of candidates to radicalisation to make them commit to a new one [Reference Bouzar and Martin30, Reference Bouzar45].

4. Discussion

4.1 Three-level model for the radicalisation process among European youths

In an attempt to summarise the main results of this review, we have developed a three-level model to explain the phenomenon of radicalisation among young Europeans since 2010. This model is shown in Fig. 2, and it follows the proposal of Doosje et al. [Reference Doosje, Moghaddam, Kruglanski, De Wolf, Mann and Feddes55]. However, it also includes some differences and the idea that some factors should be regarded as interactive factors between an individual who commits to radicalisation and a recruiter who tries to favour this process. As in Doosje et al.’s model, we distinguish individual, micro-environmental and macro-environmental factors (which are named micro-, meso- and macro-levels, respectively, in Doosje). We preferred to use the usual distinction employed in child and adolescent epidemiology of at-risk behaviour [Reference Cohen56]. The red circle encompasses the different factors that show the interaction between the subject and the radical system whatever the level: mechanisms at stake during the process of radicalisation at the individual level, similarities with the sectarian communities and the use of dehumanisation to justify the use of violence at the micro-environment level, and the proposal of a new societal model at the macro-environmental level.

Fig 2. Risk factors of radicalisation among European youth: a three-level model.

4.2 Is it possible to formulate recommendations?

The multifactorial aspect of the radicalisation process implies that the proposals imagined to prevent this phenomenon are varied. Using the three levels previously described, we synthesised the different recommendations that have been formulated inside and outside the literature review in order to prevent radicalisation. We also emphasised the proposals that have been discussed through empirical data.

At the individual level, we only find two empirical studies describing a de-radicalisation program. The first study used an anthropological perspective with a large number of French individuals [Reference Bouzar and Martin30]. They proposed a combination of socio-educative support, therapeutic groups of de-radicalisation to help individuals experiencing novel emotional associations with previous life trajectory, and family therapy [Reference Bouzar46]. No outcome data are available to date. The second study was based on a Dutch radicalisation prevention program, the DIAMANT program [Reference Feddes, Mann and Doosje57]. The training consists of three modules (‘Turning Point’, ‘Intercultural Moral Judgment’ and ‘Intercultural Conflict Management’) conducted over a period of 3 months. The first goal of DIAMANT is to help participants find a job, internship, or education in order to reduce feelings of relative deprivation and social disconnectedness. Regarding prevention, Feddes et al. reported a longitudinal study showing that improving empathy and agency skills, as well as balancing self-esteem (neither too strong nor too weak), could prevent the risk of violent radicalisation [Reference Feddes, Mann and Doosje57]. Based on case reports and series, Ludot et al reported the importance of mental health professionals meeting these young people (i) to analyse their psychological vulnerability, taking into account their political, social and cultural context, and (ii) to try to grasp the meaning radical commitment holds for them [Reference Ludot, Radjack and Moro32]. Zagury insisted that it is important for mental health professionals to offer young people psychological support without judgment [Reference Zagury15]. The lack of judgment from professionals is a necessary condition for deradicalisation. Bazex & Bénézech point out that for mental health professionals in prison, it is crucial to search for dissimulation strategies, because they hinder psychotherapeutic work [Reference Bazex, Bénézech and Mensat27].

At the micro-environment level, Van San et al. underlined the benefits of a pedagogical approach, in which a benevolent educator accompanies a young person by setting limits for him while offering him a discourse that counterbalances extremist ideologies, an approach that could prove to be relevant for prevention [Reference Van San, Sieckelinck and de Winter44]. Khosrokhavar proposed the formation of groups of imams, city officials, police officers, neighbourhood authorities and psychologists in order to show to youth accustomed to violence that a constructive dialogue exists among these people [Reference Khosrokhavar4]. According to him, repression will never be enough to combat these violent ideologies, so a preventive approach is essential. Leuzinger-Bohleber reported the case of a radicalised young man who identified a determining event in his distress: a teacher he appreciated and identified as a father figure humiliated him in class [Reference Leuzinger-Bohleber36]. Although the case per se illustrates a triggering event, she proposed setting up supervision groups for teachers, educators and social workers to raise their awareness of transference phenomena. This supervision would strengthen the ability of these professionals to offer the youth a sense of belonging and anchoring in another group than the radical group. We believe that supervision and formation should not be limited to transference phenomena but should also include social exclusion phenomena of all kinds, including first signs of radicalisation [58] and in-group out-group perspectives [Reference Fiske59].

At the macro-environmental level, Bhui et al. showed that there are modifiable risk and protective factors for the earliest stages of the radicalisation process [Reference Bhui, Warfa and Jones49, Reference Bhui, Everitt and Jones50]. They proposed a global approach centred on social inclusion/exclusion, cultural identity, acculturation, stigmatisation and political commitment [Reference Bhui, Hicks, Lashley and Jones48]. The fight against the emergence of radicalisation also involves the prevention of major depressive symptoms and the promotion of well-being and social capital. The fight against these societal risk factors would, in any case, be beneficial on a large scale, since these risk factors are also those of violence and poor health in general. Moyano explained that the polarisation between Christian and Muslim groups is certainly the ‘antechamber’ of radical commitment [Reference Moyano and Trujillo14]. Thus, he insisted on the need to pursue a policy that fights against these in-group polarisations reinforced by socio-cultural inequalities. Leuzinger-Bohleber emphasised the importance of defending freedom of expression and open dialogue around societal issues such as migration, trauma or sexuality in order to offset simplistic radical ideology [Reference Leuzinger-Bohleber36]. Khosrokhavar wondered whether non-violent Islamist fundamentalism (Salafism) could be a protective factor against radical violence [Reference Khosrokhavar4]. For him, it is important to fight against the amalgam and to mark the difference between religious fundamentalism and radical violent jihadist movements.

4.3 Implications for adolescent psychiatry

The literature review points out that radicalisation cannot be directly linked to mental illness. Individuals with psychosis are the exception rather than the rule. The resulting psychiatric treatment are suitable only for a minority of situations and there is no specific profile leading to radicalisation. However, the multiple psychological vulnerabilities as well as their similarities with the psychopathological mechanisms of adolescents with mental and behavioural difficulties (e.g. suicidality; conduct disorder; addiction) suggest a key role for adolescent psychiatry in terms of secondary and tertiary prevention. The recent report published by the French Psychiatric Federation on the link between radicalisation and psychiatry thoroughly supports the role of psychiatry [Reference Botbol, Campelo and Lacour-Gonay60]. The authors explain: (a) there is ‘an encounter between a banal process of painful adolescence and the power of the religious who, by abolishing doubt, meets the conditions of an efficient narcissistic repair’; and (b) ‘there is no specific psychopathology, but there is a specific form of expression of a common psychopathology’ of the adolescent period. As a consequence, mental health professionals can intervene in two ways to face radicalisation [Reference Rolling and Corduan28, Reference Ludot, Radjack and Moro32, Reference Botbol, Campelo and Lacour-Gonay60]. First, they have a role to play in helping adolescents or young adults to find the meaning the radical commitment has for themselves. Psychotherapeutic intervention (in individual or in group) can enable the young person to understand his personal functioning, to adopt a different point of view, beyond the political, cultural or judiciary approaches, and to find other paths than radicalisation. The links between radicalisation and adolescence psychopathology invite to consider this phenomenon from the eyes of psychiatrists or psychologists familiar with adolescence issues. Second, mental health professionals could be involved in deradicalisation programs in order to drag subjects out of their radical engagement. Knowing the specificities of adolescents and young adults in psychological treatment, they can propose adapted therapeutic devices which are ‘likely to rehumanise the functioning of the subject by reducing the factors which induced its narcissistic regression and its re-affiliation in the process of radicalisation’ [Reference Botbol, Campelo and Lacour-Gonay60]. We believe that this dynamic apprehension of the adolescent mind offers a way out of the radical commitment for a number of young subjects, whose dehumanisation and dilution within the radical group is not yet too advanced.

4.4 Study limitations and future research

Radicalisation and terrorism are major issues in our society. This article is the first multidisciplinary systematic literature review focusing on the radicalisation of young people in Europe since 2010. It tried to encompass both qualitative and quantitative studies. There is no decisive explanatory factor for radicalisation but rather a multitude of vulnerability factors that are difficult to handle in a prevention perspective. We developed a comprehensive three-level model of the radicalisation process. We believe that this broad three-level vision can be useful in understanding and apprehending the complexity of the phenomenon. Although this openness is necessarily weakening in terms of theoretical consistence of our subject, it seemed necessary to offer a holistic model in order to bring together the different fields working together on such an important subject. Besides, the fact that there is no explanatory factor is certainly explained by the epiphenomenal aspect of radicalisation whose sudden appearance is part of a complex entanglement of contextual factors. One of the specificities of adolescent psychopathology is to manifest itself in the social field [Reference Enjolras61].

However, this literature review has several biases due to the complexity of the phenomenon and the variety of youth characteristics. First, there are few empirical studies on the subject, and the inclusion criteria of the populations are highly variable (see Table 1). Most studies are qualitative studies, with a small number of subjects. This raises questions about the representativeness of some studies or the generalisation of some results outside the specific context in which the studies were performed. Second, many studies focused on subjects who had committed violent actions and who had a judicial history, which is not representative of today’s radicalised population. Third, the majority of the subjects included in the studies are men (with the notable exception of [Reference Rolling and Corduan28, Reference Bouzar and Martin30]), while it is known that the number of young radicalised women is significant. Further research is needed to broaden the scope of subjects to radicalised young women and to radicalised subjects who never committed violent actions. Finally, although our aim was to focus on young individuals, many studies selected also included adults older than 25 years questioning the generalisation of the results.

It is also fundamental to develop more empirical research using multidisciplinary approaches to the phenomenon. Different scales have been developed in order to assess sympathy for radical movements in the general population (Syfor [Reference Bhui, Warfa and Jones49], RIS [Reference Moskalenko and McCauley62], and Doosje’s scale [Reference Doosje, Loseman and van den Bos39]), but none of them has been validated. It would be useful if field professionals who have met radicalised youths were to develop an evaluation grid specifically designed for individuals perceived as at risk by the healthcare, judicial and penitentiary institutions. It is crucial to develop specific tools to study the phenomenon and to evaluate programs aimed at preventing radicalisation in order to combat this phenomenon that threatens our society.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.