1. Introduction

The college years mark the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood; a unique developmental period characterized by increasing opportunities in academic, personal, and social areas of life [Reference Arnett1]. Yet, this period also is one of heightened risk for mental disorders and risky behaviors [2–Reference Auerbach, Mortier, Bruffaerts, Alonso, Benjet and Cuijpers5]. Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), the intentional damage to one’s body tissue (e.g., scraping the skin; self-battery) without suicidal intent [6], is becoming increasingly recognized as a public health concern on college campuses. While NSSI has historically been conceptualized as a symptom of mental disorders, there is now increased awareness that NSSI is not symptomatic of any particular disorder and should be conceptualized as a behavior that warrants research and intervention in its own right [7–Reference Bentley, Cassiello-Robbins, Vittorio, Sauer-Zavala and Barlow12]. International pooled lifetime prevalence estimates of NSSI are around 20% in college students [Reference Swannell, Martin, Page, Hasking and St John13], with 12-month estimates in the 2–14% range [Reference Serras, Saules, Cranford and Eisenberg14, Reference Wilcox, Arria, Caldeira, Vincent, Pinchevsky and O’Grady15]. Although not always associated with suicide risk, NSSI (especially repetitive and severe self-injury) is one of the strongest independent predictors of future suicide attempts [16–Reference Ribeiro, Franklin, Fox, Bentley, Kleiman and Chang19], and is associated with severe role impairment in daily life [Reference Kiekens, Hasking, Claes, Mortier, Auerbach and Boyes9], stigma and feelings of shame [Reference Burke, Piccirillo, Moore-Berg, Alloy and Heimberg20, Reference VanDerhei, Rojahn, Stuewig and McKnight21], low levels of help-seeking [Reference Gollust, Eisenberg and Golberstein22, Reference Whitlock, Muehlenkamp, Purington, Eckenrode, Barreira and Abrams23], and poorer academic performance [Reference Kiekens, Claes, Demyttenaere, Auerbach, Green and Kessler24]. These findings underscore the necessity to address and respond to NSSI among college students [Reference Lewis, Heath, Hasking, Whitlock, Wilson and Plener25].

Although many colleges have begun to implement risk assessment and prevention programs for mental health problems [Reference Harrer, Adam, Fleischmann, Baumeister, Auerbach and Bruffaerts26, Reference Bendtsen, Bendtsen, Karlsson, White and McCambridge27], NSSI is rarely included in these efforts. Importantly, however, although NSSI onset peaks in mid-adolescence [Reference Plener, Schumacher, Munz and Groschwitz28], recent evidence suggests a second peak around the age of 20 [Reference Gandhi, Luyckx, Baetens, Kiekens, Sleuwaegen and Berens29]. Hence, there is potential to reach out to students before NSSI and associated negative outcomes occur. Franklin and colleagues recently demonstrated a reduction in frequency of NSSI through use of a mobile app that focuses on the barriers to NSSI (e.g., by increasing self-worth) [Reference Franklin, Fox, Franklin, Kleiman, Ribeiro and Jaroszewski30]. It is possible that similar initiatives may be effective in preventing onset among at risk students. However, there is not yet any evidence-based method of identifying students at risk for onset of NSSI. This is in part due to two important limitations in the literature. First, most of what is known about potential risk factors stems from cross-sectional approaches investigating correlates among convenience samples. Whereas these studies can provide clues about potential predictors of interest, the nature of the designs and samples limit the generality of the findings [Reference Kraemer, Kazdin, Offord, Kessler, Jensen and Kupfer31]. Second, the prospective studies available focused primarily on risk factors for NSSI persistence (i.e., ongoing vs. ceased NSSI) [Reference Wilcox, Arria, Caldeira, Vincent, Pinchevsky and O’Grady15, 32–Reference Kiekens, Hasking, Bruffaerts, Claes, Baetens and Boyes35]. While these studies provide valuable information to aid clinical decision making for persons who already engage in NSSI, it does not provide means to detect young adults who are likely to start engaging in NSSI. Two earlier studies reported 9-12-month onset rates in the 2–4% range in college students [Reference Riley, Combs, Jordan and Smith33, Reference Hamza and Willoughby34]. However, these studies may have failed to include a representative college sample (e.g., only college women, convenience sampling) and incorporated a narrow set of predictors, precluding the development of integrative prediction models to detect students at highest risk for NSSI onset. We aimed to address these gaps in the literature making use of a large longitudinal sample of college students from the Leuven College Surveys (LCS) [36], part of the WHO World Mental Health International College Student (WMH-ICS) initiative [37].

Our objectives were to: 1) estimate the incidence of NSSI during the first two years of college, 2) examine a broad range of proximal and distal risk factors, and 3) evaluate the accuracy of a multivariate risk prediction model for the onset of NSSI. In line with the proposition that NSSI is a complex behavior that is determined by a multitude of factors [Reference Nock38], we did not anticipate a clear set of risk factors for onset NSSI. Potential predictors we assessed are well-established correlates of NSSI in college students, including sociodemographic and college-related characteristics [Reference Whitlock, Muehlenkamp, Purington, Eckenrode, Barreira and Abrams23, Reference Kiekens, Claes, Demyttenaere, Auerbach, Green and Kessler24], childhood-adolescent trauma [39–Reference Martin, Bureau, Yurkowski, Fournier, Lafontaine and Cloutier41], recent stressful experiences and perceived social support [Reference Wilcox, Arria, Caldeira, Vincent, Pinchevsky and O’Grady15, Reference Kiekens, Hasking, Bruffaerts, Claes, Baetens and Boyes35, Reference Taliaferro and Muehlenkamp40], and mental disorders [Reference Kiekens, Hasking, Claes, Mortier, Auerbach and Boyes9, Reference Bentley, Cassiello-Robbins, Vittorio, Sauer-Zavala and Barlow12, Reference Taliaferro and Muehlenkamp42]. Consistent with the proposed DSM-5 frequency criterion (i.e., self-injury on 5 or more days in the past year) [43], we determined the predictive value of risk factors separately for the onset of both sporadic and repetitive NSSI (i.e., ≥ 5 times per year), occurring during the first two years of college.

2. Method

2.1. Procedures and sample description

Detailed recruitment strategies of the LCS have previously been described [Reference Mortier, Demyttenaere, Auerbach, Cuijpers, Green and Kiekens4, Reference Kiekens, Claes, Demyttenaere, Auerbach, Green and Kessler24]. Recruitment involved different strategies to increase the response rate. In the first phase, all incoming students were sent a standard invitation letter to a routine psycho-medical checkup organized by the university student health center, which included the survey. In the second phase, secured electronic links were sent to non-respondents using customized e-mails. The third phase was identical to the second, but included an additional incentive (i.e., a raffle for store coupons). Each phase included reminders, with eight as default maximum amount of contacts. In the academic years 2014-2015 and 2015-2016, all 8,530 first year students were invited to participate, and a total of 4,565 students completed the baseline survey (56.8% female, Mage = 18.3, SD = 1.1; Response Rate = 53.5%). Baseline responders were invited via email, to participate in the follow-up surveys 12 and 24 months after the baseline assessment. A total of 2,163 of the baseline respondents participated in at least one follow-up survey (63.2% conditional response rate after adjusting for non-participation due to college attrition). Informed consent was obtained from all participants at each wave and the study’s protocol was approved by the University’s Ethical Review Board.

2.2. Measures

Sociodemographic and college-related variables included gender, age, nationality, perceived parental financial situation, parental educational level, family composition, subject area enrollment (e.g., biomedical sciences, science and technology), and type of secondary school attended (i.e., vocational vs. academic track).

Non-suicidal self-injury was assessed with the self-report version of the well-validated Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview [Reference Nock, Holmberg, Photos and Michel44]. The self-report version showed excellent test-retest reliability and external validity in a comparison study of self-report questionnaires [Reference Latimer, Meade and Tennant45]. To assess lifetime NSSI thoughts, we asked respondents whether they ever had “thoughts of purposely hurting themselves, without wanting to die”. Incident NSSI was assessed via a checklist of 13 NSSI methods (e.g., cutting, burning, hitting) and an ‘other’ category that asked respondents whether they used that NSSI method to “hurt themselves on purpose, without wanting to die”. Using follow-up questions, we assessed whether students engaged in 12-month sporadic (i.e., 1–4 times) or repetitive NSSI (i.e., ≥ 5 times).

Traumatic experiences prior to the age of 17 were assessed using 19 items from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview-3.0 [CIDI; 46], the Adverse Childhood Experience Scale [Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Am and Edwards47], and the Bully Survey [Reference Swearer and Cary48]. Items assessed parental psychopathology (i.e., any serious mental health problems, criminal activities, or interpersonal violence), physical abuse (e.g., family member hit you so hard that it left bruises), emotional abuse (e.g., family member repeatedly said hurtful or insulting things), sexual abuse (e.g., family member touched or made you touch them in a sexual way against your will), neglect (i.e., nobody took care of you, or protected you, or made sure you had the things you needed), dating violence (i.e., you were in a romantic relationship where your partner repeatedly hit you or hurt you) and bully victimization (including verbal, physical, and cyberbullying). Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale (“never,” “rarely,” “sometimes,” “often,” and “very often”). Previous research using confirmatory factor analysis showed an excellent fit of the factor structure of the used items [Reference Mortier, Demyttenaere, Auerbach, Cuijpers, Green and Kiekens4]. In order to obtain dichotomously coded variables for the calculation of population attributable risk proportions, “rarely” was used as the cutoff for experiencing each traumatic event, except bully victimization where “sometimes” was used as cutoff [Reference Nansel, Overpeck, Pilla, Ruan, Somins-Morton and Scheidt49].

Stressful experiences and perceived social support. Making use of well-validated screeners [50–Reference Vogt, Proctor, King, King and Vasterling52], we assessed a range of 12-month stressful experiences (e.g., life-threatening illness or injury of family member or close friend). Using the Social Network section of the CIDI-3.0 [Reference Kessler and Ustün46], participants indicated whether they felt they could rely on family, friends, and partner (when present) if they had a serious problem. Items were rated on a four-point scale (“a lot”, “some”, “a little”, and “not at all”). To allow the calculation of population attributable risk proportions, networks that were perceived as unavailable for support “a lot” were coded as unsatisfactory.

Risk for mental disorders and associated impairment. The CIDI Screening Scales [Reference Kessler and Ustün46, Reference Kessler, Calabrese, Farley, Gruber, Jewell and Katon53], developed by the World Health Organization to deliver prevalence estimates of DSM-IV mental disorders, were used to assess 12-month Major Depressive Disorder, Broad Mania (mania/hypomania), Generalized Anxiety Disorder, and Panic Disorder. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) was used to identify students engaging in “risky or hazardous drinking” and students with “risk for alcohol dependence” [Reference Demartini and Carey54]. Using additional items from the CIDI-3.0, we also screened students for intermittent explosive disorder (i.e., history of repeated attacks of anger when suddenly you lost control and either broke or smashed something, hit or tried to hurt someone, or threatened someone), eating disorders (i.e., binges at least twice a week or history of vomiting or taking laxatives or other things to avoid gaining weight), psychotic disorder (i.e., history of seeing things other people couldn't see or hear, or having thoughts like believing your mind was being controlled by outside forces) and post-traumatic stress disorder (i.e., times lasting 1 month or longer after an extremely stressful experience when you had repetitive upsetting memories or dreams, felt emotionally distant or depressed, and had trouble sleeping or concentrating). Finally, using the Sheehan Disability Scale, 12-month severe role impairment in daily life was assessed [Reference Kessler and Ustün46, Reference Kessler, Heeringa, Stein, Colpe, Fullerton and Hwang55].

Twelve-month suicidal thoughts and behaviors were assessed with a modified version of the Columbia Suicidal Severity Rating Scale and included suicide ideation (i.e., having thoughts of killing yourself), suicide plan (i.e., thinking about how you might kill yourself or working out a plan of how to kill yourself), and a suicide attempt (i.e., purposefully hurt yourself with at least some intent to die) [Reference Posner, Brown, Stanley, Brent, Yershova and Oquendo56].

2.3. Statistical analyses

Appropriate missing data strategies were used to ensure that findings are representative for the entire student population. Specifically, non-response propensity weights were calculated based on sociodemographic and college-related variables available for the entire first year cohort [Reference Kiekens, Claes, Demyttenaere, Auerbach, Green and Kessler24], and multivariate imputation by chained equations was used to adjust for survey attrition and within-survey item nonresponse [Reference Van Buuren57]. Using the package mice() in R [Reference Van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn58], the final data consisted of 200 imputed datasets obtained after 100 iterations. For the purpose of this study, analyses were restricted to students reporting no prior history of NSSI at baseline (n = 3,761). Descriptive statistics and incidence estimates are reported as weighted numbers (n), and weighted proportions (%) with associated standard errors. One-year NSSI incidence proportions were calculated by using first onset NSSI follow-up cases as the numerator, and cases without NSSI at the previous wave as the denominator. Logistic regression analysis was used to test the strength of associations between risk indicators recorded at baseline and incident NSSI. Measures of association were reported as odds ratios and associated 95% confidence intervals. Each risk factor was evaluated in bivariate and multivariate models within risk domains. Population-level effect sizes were estimated using population attributable risk proportions [PARPs; Reference Kessler, Harkness, Heeringa, Pennel, Zaslavsky, Borges, Nock, Borges and Ono59]. PARPs provide an estimate of the proportion of cases that would potentially be prevented if it were possible to fully eliminate causal risk factor(s) under examination.

Based on multivariate equations including all risk factors in the study (>50 beta coefficients), we then calculated individual cumulative risk probabilities. Resulting Area Under the Curve (AUC) values close to.56,.64, and.71 are considered, respectively, as small, moderate, and large effects [Reference Rice and Harris60]. Predicted probabilities were discretized into deciles (10 groups of equal size ordered by percentiles) and cross-classified with observed cases to visualize the concentration of risk associated with high composite predicted probabilities. Sensitivity was defined as the proportion of cases found among pre-defined proportions of respondents with the highest predicted probabilities. Positive predictive value (PPV) was defined as the probability of students developing NSSI when estimated among predefined proportions of respondents with the highest predicted probabilities. We used the method of leave-one-out cross-validation to correct for the over-estimation of prediction accuracy when both estimating and evaluating model fit in a single sample [Reference Efron and Gong61]. Firth’s penalized likelihood estimation was applied to avoid overfitting and inconsistent estimators due to data sparseness [Reference Heinze62]. All analyses were performed with SAS (version 9.4) and R (version 3.5.1).

3. Results

3.1. Incidence of NSSI during college

The 12-month incidence of NSSI was estimated at 10.3% (SE = 0.8) in year 1, and 6.0% (SE = 0.7) in year 2. Aggregated rates of onset of NSSI were estimated at 15.6% (SE = 0.9) during the first two college years, with 8.6% (SE = 0.8) reporting sporadic NSSI and 7.0% (SE = 0.6) reporting repetitive NSSI. The three most commonly reported methods were smashing hand or foot against the wall or other objects (52.0%, SE = 3.5), scraping the skin (37.3%, SE = 3.3), and hitting oneself (35.1%, SE = 3.1).

3.2. Bivariate and multivariate risk factors for onset of NSSI

The investigation of different risk factor domains revealed the following key findings at the individual-level. First, the most important sociodemographic and college-related variable that predicted NSSI onset was vocational secondary school track (Table 1). Second, while a variety of traumatic experiences prior to the age of 17 predicted both sporadic and repetitive NSSI (Table 2), in multivariate models only dating violence, emotional abuse, and bully victimization were significant predictors of both forms of NSSI.

Third, in bivariate models, an examination of the temporal associations between 12-month stressful experiences and incident NSSI revealed that several proximal interpersonal stressors (e.g., serious betrayal by someone other than partner) were predictive of sporadic and/or repetitive NSSI (Table 3). However, in multivariate models only unsatisfactory peer support predicted both forms of NSSI. Repetitive NSSI was also significantly associated with unsatisfactory family support, serious ongoing arguments or break-ups, and other stressful events. Fourth, all mental disorders and symptoms of psychopathology were consistently associated with increased risk for sporadic and/or repetitive onset of NSSI, with the only exception being alcohol use disorder (Table 4). In multivariate models, however, only 12-month suicidal ideation and severe role impairment in daily life were uniquely predictive of both forms of NSSI.

Next, we determined the potential population-level impact of the examined risk domains for the onset of NSSI. Assuming a causal association, we estimated that one third of sporadic NSSI (PARP = 32.9%), and nearly one half of repetitive NSSI (PARP = 46.0%), occurring for the first time in college, might have been preventable if it were possible to prevent any childhood-adolescent traumatic experiences. Somewhat smaller PARPs were observed for 12-month stressful experiences for onset of sporadic (PARP = 21.5%) and repetitive (PARP = 34.9%) NSSI. The highest PARPs (sporadic = 37.8%; repetitive = 51.1%), however, were found for mental disorders and symptoms of psychopathology. The single most important risk factors at the population-level were bully victimization for sporadic NSSI (PARP = 11.3%) and unsatisfactory peer support for repetitive NSSI (PARP = 14.0%).

Table 1 Sociodemographic and college-related variables as baseline predictors for onset of non-suicidal self-injury.

Note: a Prevalence estimate of potential risk factors among those without a history of NSSI at baseline, b Bivariate associations are based on separate models for each row, with the variable in the row as predictor, c Multivariate associations are based on all factors shown in the table, d high education level was defined as holding at least a bachelor’s degree, e defined as partents divorced or separated. w(n) = weighted number of cases, w(%) = weighted percentage of sample, OR = Odds Ratio; PARP = Population Attributable Risk Proportion; Significant odds ratios and PARPs are shown in bold (α =.05).

Table 2 Childhood-adolescent traumatic experiences (< 17 years) as baseline predictors for onset of non-suicidal self-injury.

Note: a Prevalence estimate of potential risk factors among those without a history of NSSI at baseline, b Bivariate associations are based on separate models for each row, with the variable in the row as predictor, c Multivariate associations are based on all factors shown in the table. w(n) = weighted number of cases, w(%) = weighted percentage of sample, OR = Odds Ratio; PARP = Population Attributable Risk Proportion; Significant odds ratios and PARPs are shown in bold (α =.05).

3.3. Evaluation of the accuracy of an integrative risk prediction model for onset of NSSI

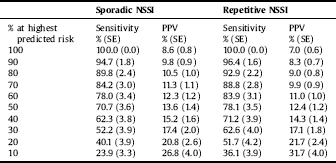

Finally, we constructed multivariate models that included all factors in the study to predict NSSI onset. Most risk factors became non-significant in these integrative prediction models (see supplementary Table 1), with the exception of dating violence prior to age 17 (for repetitive NSSI; OR = 3.1) and severe role impairment in daily life (ORs in the 1.8–1.9 range). The generated cumulative risk probabilities showed reasonable-to-good performance for detecting onset of both sporadic and repetitive NSSI (Table 5). Cross-validated sensitivity estimates for different proportions of students at highest predicted risk show that an intervention that, for instance, targets the 10% at highest risk would effectively reach 23.9% (SE = 3.3) of students who report sporadic, and 36.1% (SE = 3.9) of students who report repetitive NSSI, for the first-time during college. The incidence of NSSI in these subgroups would be 26.8% and 31.7%, respectively.

4. Discussion

This study presents a comprehensive examination of incident NSSI in college students. Three main findings stand out. First, the incidence of NSSI was estimated at 10.3% in year 1 and 6.0% in year 2, with 7.0% reporting onset of repetitive NSSI during the first two years of college. Second, as expected, there was no single stand-out risk factor for NSSI onset. Rather, a broad range of distal and proximal risk factors were prospectively associated with both sporadic and repetitive NSSI onset. Third, our findings show that it is possible to develop risk assessment algorithms, focused on a broad, yet feasible, range of clinically meaningful risk factors, to identify and potentially provide targeted interventions to students at high risk for onset of NSSI during college.

This is the first European study to investigate the incidence of NSSI in emerging adults. Despite evidence that emerging adulthood is a sensitive period for the onset of mental disorders and risky behaviors [2–Reference Auerbach, Mortier, Bruffaerts, Alonso, Benjet and Cuijpers5], the incidence of NSSI has rarely been studied outside of adolescence. The reported incidence rates are higher than two earlier American-Canadian estimates [2–4% range; Reference Riley, Combs, Jordan and Smith33, Reference Hamza and Willoughby34]. Possible explanations may include geographical or methodological differences (i.e., we used a representative sample and made use of an exhaustive NSSI checklist [Reference Kimbrel, Thomas, Hicks, Hertzberg, Clancy and Elbogen63]), cohort effects (i.e., increasing rate of NSSI [Reference Wester, Trepal and King64, Reference Gillies, Christou, Dixon, Featherston, Rapti and Garcia-Anguita65]), or a combination of these. On balance, our findings confirm recent work in finding a second NSSI onset peak in emerging adulthood [Reference Gandhi, Luyckx, Baetens, Kiekens, Sleuwaegen and Berens29], and suggest that - although the majority of students who report onset of NSSI will not meet DSM-5 disorder criteria [Reference Kiekens, Hasking, Claes, Mortier, Auerbach and Boyes9] - a large number of young adults will self-injure for the first time in college. Consistent with studies that show that the transition to college can be a particularly stressful event [Reference Bruffaerts, Mortier, Kiekens, Auerbach, Cuijpers and Demyttenaere3, Reference Dyson and Renk66, Reference Robotham67], our findings suggest that especially incoming college students are at high risk for onset of NSSI. Interestingly, although our rates of cutting were similar to other studies [Reference Hamza and Willoughby34], self-cutting was not among the most frequently reported methods. We speculate that because most individuals in our onset sample report sporadic NSSI, more severe NSSI methods such as self-cutting might be less frequently reported as early methods of NSSI. We found some evidence for this as self-cutting was more prevalent among those who reported repetitive NSSI (sporadic NSSI = 11.8% vs. repetitive NSSI = 29.0%).

Table 3 Twelve-month stressful experiences and perceived social support as baseline predictors for onset of non-suicidal self-injury.

Note: a Prevalence estimate of potential risk factors among those without a history of NSSI at baseline, b Bivariate associations are based on separate models for each row, with the variable in the row as predictor, c Multivariate associations are based on all factors shown in the table. w(n) = weighted number of cases, w(%) = weighted percentage of sample, OR = Odds Ratio; PARP = Population Attributable Risk Proportion; Significant odds ratios and PARPs are shown in bold (α =.05).

Table 4 Risk for 12-month mental disorders, 12-month suicidal thoughts and behaviors, and associated impairment as baseline predictors for onset of non-suicidal self-injury.

Note: a Prevalence estimate of potential risk factors among those without a history of NSSI at baseline, b Bivariate associations are based on separate models for each row, with the variable in the row as predictor, c Multivariate associations are based on all factors shown in the table. w(n) = weighted number of cases, w(%) = weighted percentage of sample, OR = Odds Ratio; PARP = Population Attributable Risk Proportion; Significant odds ratios and PARPs are shown in bold (α =.05).

Table 5 Concentration of risk for onset of NSSI in different proportions of first year students at highest predicted risk based on the final multivariate risk model.

Note: see the multivariate models including all predictors across risk domains in supplementary materials. Model-based AUC values were 0.73 (0.02) for sporadic onset NSSI and 0.79 (0.02) for repetitive onset of NSSI. Cross-validated AUC values were 0.70 (0.03) for sporadic onset and 0.75 (0.02) for repetitive onset of NSSI. Sensitivity = proportion of onset cases found among row% of responders at highest predicted risk, based on cross-validated predicted probabilities. Positive Predictive Value = probability of effectively developing onset when being among row% of responders at highest predicted risk, based on cross-validated predicted probabilities.

With respect to prospective risk factors for first onset NSSI, there are three findings that require brief comment. First, we found evidence that the pathogenic effect of early trauma extends vulnerability for NSSI into emerging adulthood [Reference Liu, Scopelliti, Pittman and Zamora39]. Previous research has shown that early trauma is associated with neurobiological and psychological changes that impede intrapersonal (e.g., self-critical attribution style) and interpersonal functioning (e.g., relational schemas of mistrust) [68–Reference Serafini, Muzio, Piccinini, Flouri, Ferrigno and Pompili70]. It is worth mentioning within this context that the effect of neglect and all subtypes of abusive family relationships were attenuated when bullying and dating violence were taken into account, suggesting that the former may increase risk through re-victimization in peer and partner relationships [Reference Crawford and Wright68, Reference Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt and Kim71, Reference Van Geel, Goemans and Vedder72]. Second, findings from this study also highlight the significance of proximal negative interactions for incident NSSI. Consistent with recent work showing the importance of positive peer relationships in mitigating risk for NSSI in emerging adults [Reference Kiekens, Hasking, Bruffaerts, Claes, Baetens and Boyes35, Reference Turner, Wakefield, Gratz and Chapman73], we found that limited peer support was associated with the onset of sporadic and repetitive NSSI for approximately one in ten students who self-injured. Third, supporting the conceptualization of NSSI as a trans-diagnostic behavior [Reference Bentley, Cassiello-Robbins, Vittorio, Sauer-Zavala and Barlow12], most mental health problems were prospectively associated with sporadic and repetitive NSSI. Multivariate models suggest that the associated role impairment might partially account for these associations.

A novel and perhaps the most important contribution of our study was the development of an integrative multivariate prediction model that yields reasonable prediction accuracy for detecting students at high risk of beginning NSSI during their academic career. Consistent with recent advances in depression and suicide prevention research [Reference Mortier, Demyttenaere, Auerbach, Cuijpers, Green and Kiekens4, Reference Ebert, Buntrock, Mortier, Auerbach, Weisel and Kessler74], risk screening at college entrance may provide a unique approach to identify those at risk for future NSSI and offer timely intervention. Specifically, by offering evidence-based intervention to the top 10% at greatest risk of NSSI onset, our data suggest that we could theoretically prevent nearly one in four sporadic and two in five repetitive onset cases. This figure would increase to more than half of students who report repetitive NSSI if we target the top 20% at risk, although this would also increase the risk of identifying false positives (i.e., students who would never have self-injured). However, it could also be argued that these students may still benefit from a general mental health promotion intervention because of their constellation of clinically significant risk factors. While these findings are promising, further research will almost certainly be able to improve these models by including protective factors (e.g., emotion regulatory capability), NSSI-related cognitions (e.g., self‐efficacy to resist NSS), and allowing for interactions in larger samples. Building upon these findings, the next logical step would then be to determine how preventive interventions could best be delivered (e.g., making use of the high scalability of internet- and mobile-based applications) and which type of interventions (i.e., trans-diagnostic vs. NSSI-specific) work best for students at varying levels of risk. Addressing these questions in future research will be extremely important to help guide and fully exploit the potential of individualized screening and preventive approaches for NSSI in college. Taken together, the current findings show that effectively dividing college entrants into low and high-risk groups by means of an empirically-derived prediction model has the potential to help optimize the deployment of preventive interventions aimed at reducing the incidence of NSSI and its potentially negative consequences (e.g., increased capability for suicide [Reference Willoughby, Heffer and Hamza75]).

Several limitations deserve attention in interpreting the results of this study. First, response rates in the 54–63% range are sub-optimal. We used state-of-the-art missing data handling techniques to tackle potential residual non-response bias, however, this remains a concern. Second, we used validated clinical screening scales instead of full diagnostic interviews to assess risk for mental disorders; hence, these prevalence rates should be interpreted cautiously. Third, the extent to which the identified risk factors are also causally predictive of NSSI onset cannot be resolved with our current approach. The best way to resolve this uncertainty is to carry out randomized trials that evaluate the effectiveness of targeting the identified risk factors. Finally, because our results are based on data from one college, replicating the findings represents an important goal for future research.

5. Conclusion

The current study makes significant advances to both science and practice by estimating the incidence of NSSI in college students and examining clinically useful prediction models that can identify students at risk for future NSSI. Results show that the college years are a sensitive period for the onset of NSSI. While our findings shed light on many risk factors for sporadic and repetitive incident NSSI, effect sizes of individual prospective associations were weak to moderate. Importantly, however, combining risk factors from multiple domains into an integrative prediction model enabled us to detect college entrants at high cumulative risk for incident NSSI with a reasonable degree of accuracy. Further research in this area has the potential to deliver a powerful and cost-beneficial tool that will be valuable in planning future preventive interventions for NSSI in college populations worldwide.

Declaration of interest

In the past 3 years, Dr. Kessler received support for his epidemiological studies from Sanofi Aventis, he was a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention, Shire and Takeda, and served on an advisory board for the Johnson & Johnson Services Inc. Lake Nona Life Project. Dr. Kessler is a co-owner of DataStat, Inc., a market research firm that carries out healthcare research. The other authors have no interests to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the student services of KU Leuven for their assistance in data collection. This research was supported in part by grants from the Research Foundation Flanders [11N0514N (PM), 11N0516N (PM), 1114717N (GK), 1114719N (GK)], King Baudouin Foundation [2014‐J2140150‐102905 (RB)], a New Independent Researcher Infrastructure Support Award [Department of Health, Government of Western Australia (MB)] and Curtin University [CIPRS/HSFIRS (GK)]. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.04.002.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.