1 Introduction

Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are mental disorders with serious implications for quality of life and overall health issues [Reference Bortolato, Miskowiak, Kohler, Vieta and Carvalho1–Reference Laursen, Wahlbeck, Hallgren, Westman, Osby and Alinaghizadeh6]. Patients suffer from a considerable physical health burden, with cardiovascular diseases as a main cause of early death [Reference Laursen, Wahlbeck, Hallgren, Westman, Osby and Alinaghizadeh6–Reference Laursen, Munk-Olsen and Gasse8]. Efficient treatment requires a series of measures, including use of psychotropic drugs, of which some are associated with metabolic adverse effects [Reference Rummel-Kluge, Komossa, Schwarz, Hunger, Schmid and Lobos9–Reference Leucht, Cipriani, Spineli, Mavridis, Örey and Richter11]. Concomitant drug treatment is often required due to the complex array of symptoms Reference Moller, Seemuller, Schennach-Wolff, Stubner, Ruther and Grohmann[12].

In schizophrenia, combining a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) with an antipsychotic has been linked to improvement of negative symptoms beyond the effect exerted by the antipsychotic agent in monotherapy Reference Rummel, Kissling and Leucht[13]. Although SSRIs are used to treat depressive and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia as well, the limited data available prevents any definitive recommendations for their use in these cases Reference Buoli, Serati, Ciappolino and Altamura[14].

In bipolar disorder, antidepressants are often administered for acute depression Reference Baldessarini, Leahy, Arcona, Gause, Zhang and Hennen[15], but is generally discouraged as monotherapy due to the risk of switching to hypomania/mania, rapid cycling or increased suicidal ideation [Reference Pacchiarotti, Bond, Baldessarini, Nolen, Grunze and Licht16, Reference Perlis, Ostacher, Goldberg, Miklowitz, Friedman and Calabrese17]. Co-medication with mood stabilizers or antipsychotic drugs is therefore recommended and consistent with practice guidelines [Reference Ketter, Miller, Dell’Osso, Calabrese, Frye and Citrome18–Reference Goodwin, Haddad, Ferrier, Aronson, Barnes and Cipriani20]. These disorders as well as the use of antipsychotic drugs as such are linked to cardiovascular diseases [Reference Laursen, Wahlbeck, Hallgren, Westman, Osby and Alinaghizadeh6–Reference Rummel-Kluge, Komossa, Schwarz, Hunger, Schmid and Lobos9, Reference Leucht, Cipriani, Spineli, Mavridis, Örey and Richter11, Reference Ringen, Engh, Birkenaes, Dieset and Andreassen21]. The metabolic implications of SSRI augmentation of antipsychotic treatment should also be considered.

A few previous studies have addressed the metabolic adverse effects related to SSRIs and antipsychotics used in combination. Olanzapine and fluoxetine are the most frequently studied combination. A pooled analysis of data from five acute phase studies of patients with treatment resistant depression showed a significantly greater increase in total cholesterol when olanzapine and fluoxetine were combined, as compared to olanzapine monotherapy [Reference Trivedi, Thase, Osuntokun, Henley, Case and Watson22–Reference Shelton, Williamson, Corya, Sanger, Van Campen and Case26]. In contrast, in an 8-week double blind randomized controlled trial in bipolar disorder, non-significant increases in serum cholesterol, glucose and body weight were found in the olanzapine plus fluoxetine group compared to olanzapine alone Reference Tohen, Vieta, Calabrese, Ketter, Sachs and Bowden[27]. Additionally, in a study of patients with bipolar depression, no differences in lipid levels were found between the olanzapine plus fluoxetine group and the olanzapine monotherapy group Reference Tamayo, Sutton, Mattei, Diaz, Jamal and Vieta[28]. Finally, in a study based on the World Health Organization database for spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions, SSRIs were found to be a significant risk factor for glucose intolerance when administered in combination with clozapine, olanzapine and risperidone Reference Hedenmalm, Hagg, Stahl, Mortimer and Spigset[29].

As there has been little effort toward addressing the risk of metabolic adverse effects when antipsychotics and SSRIs are used in combination, the aim of the present study was to investigate the metabolic effects of SSRIs in combination with antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. In order to relate the outcomes to the degree of exposure, the dose and the serum concentrations of SSRIs and antipsychotics were used as exposure variables.

2 Material and method

2.1 Subjects

The Thematically Organized Psychosis (TOP) Study at the University of Oslo in Norway consists of a sample of patients with schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar disorders recruited from the in- and outpatient wards of the university hospitals in Oslo. Inclusion criteria were meeting the DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, age from 18 to 65 years and being willing and able to give an informed consent of participation. Demographic data and information of pharmacological treatment were collected through interviews and medical records. Procedures of data collection and diagnostic and symptom assessment of the TOP study is thoroughly described elsewhere Reference Birkenaes, Opjordsmoen, Brunborg, Engh, Jonsdottir and Ringen[30].

The Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, South East Norway and the Norwegian Data Protection Agency approved the study. In total, 1301 patients were available at the time of the data extraction. Demographic characteristics of the patients are listed in Table 1 and are also described in further detail in a previous publication Reference Fjukstad, Engum, Lydersen, Dieset, Steen and Andreassen[31].

2.2 Variables

2.2.1 Outcomes

The serum levels of total cholesterol was the primary outcome variable, as it is considered one of the most important risk factors for cardiovascular disease Reference Shay, Gooding, Murillo and Foraker[32]. Low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-cholesterol), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-cholesterol), triglycerides, glucose, body mass index (BMI) and systolic and diastolic blood pressure were chosen as secondary outcome variables.

Fasting serum concentrations of total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides and glucose were analyzed at Department of Clinical Chemistry, Oslo University Hospital, using an Integra 800 instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) according to standard methods. The height of each individual was measured with standard methods, body weight (with light clothes) was weighed on calibrated digital weights (Soehnle, Nassau, Germany), and BMI (kg/m2) was thereafter calculated. A physician measured resting blood pressure manually, using a sphygmomanometer (Boso, Jungingen, Germany).

2.2.2 Exposure variables

To analyze comparable dosages of each drug, the daily dose for each patient was expressed in relationship to the defined daily dose (DDD) [33]. The following DDDs were applied: 10 mg for olanzapine, 400 mg for quetiapine, 5 mg for oral risperidone, 2.7 mg for intramuscular depot risperidone, 10 mg for escitalopram, 20 mg for citalopram, fluoxetine and paroxetine and 50 mg for sertraline. Thus, a patient using e.g. a daily dose of 10 mg citalopram was defined as using an SSRI dose 0.5 DDD per day.

Similarly, the measured serum concentration of each drug was divided by the middle value of the drug's reference interval Reference Hiemke, Baumann, Bergemann, Conca, Dietmaier and Egberts[34], hereinafter referred to as the “reference serum concentration”, to provide comparable concentration variables between different drugs. The middle values (reference intervals in parentheses) applied were 160 (65–255) nmol/L for olanzapine, 780 (260–1300) nmol/L for quetiapine, 95 (50–140) nmol/L for risperidone plus the active metabolite 9-hydroxyrisperidone, 142 (45–240) nmol/L for escitalopram, 240 (150–330) nmol/L for citalopram, 260 (35–490) nmol/L for sertraline, 1025 (400–1650) nmol/L for fluoxetine plus the active metabolite norfluoxetine and 225 (90–360) nmol/L for paroxetine Reference Hiemke, Baumann, Bergemann, Conca, Dietmaier and Egberts[34]. The serum concentrations of all drugs were analyzed at the Department of Clinical Pharmacology, St Olav University Hospital by analytical methods described in detail previously [Reference Reis, Aamo, Spigset and Ahlner35, Reference Soderberg, Wernvik, Tillmar, Spigset, Kronstrand and Reis36].

2.3 Statistical analyses

The missing serum concentrations (numbers missing in parentheses) for the antipsychotics olanzapine (n=68), quetiapine (n=39) and risperidone (n=17) and the SSRIs escitalopram (n=39), citalopram (n=8), sertraline (n=6), fluoxetine (n=6) and paroxetine (n=1), were imputed with single imputation. The expectation maximization algorithm was applied separately for each substance, using the DDD, age and gender as predictors. The remaining missing values were imputed by multiple imputation. Seventy-seven variables were imputed, and we imputed 100 data sets as recommended by van Buuren Reference van Buuren[37]. The imputed data set included every variable used in the analyses as well as a group of variables thought to be supplementary predictors (numbers missing in parenthesis): height (n=96), body weight (n=104), heart rate (n=149), Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia score (CDSS) (n=402) and use of snuff (n=61). The variables used in the imputation were not transformed, as advocated by Rodwell et al. Reference Rodwell, Lee, Romaniuk and Carlin[38].

Linear regression was performed with total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, BMI and systolic and diastolic blood pressure as dependent variables, one at a time. Covariates were the antipsychotic drug (olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone), the SSRI and their interaction. Exposure was expressed as daily doses or serum concentrations separately. Normality of residuals was assessed by visual inspection of Q-Q plots. The assumption of normality was violated in the case of triglycerides and glucose.

Table 1 Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) related to demographic variables, diagnosis, symptoms and use of concomitant medication among 1301 patients included in the study based on complete cases. According to the type of variable, data are presented either as means with standard deviations in parenthesis or as numbers with percentages in parentheses.

LDL-cholesterol: low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-cholesterol: high density lipoprotein cholesterol; BMI: body mass index; BP: blood pressure.

a IDS: Inventory of Depression Symptomatology.

b YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale.

c PANSS: Positive and Negative Symptom Scale.

d One alcohol unit equals 15 ml of 40% alcohol or 12.8 g alcohol.

e First generation high potency antipsychotics: perphenazine, haloperidol, flupenthixol and zuclopenthixol.

f First generation low potency antipsychotics: levomepromazine, chlorpromazine and chlorprothixene.

g Weight inducing mood stabilizers: valproate and gabapentin.

h Numbers of missing for IDS in total.

Results are presented unadjusted and with adjustment for of all potential confounding factors (numbers missing in parentheses): age (n=0), gender (n=0) marriage/cohabitation/partnership (n=6), diagnosis (n=0), previous episodes of depression (n=104) [Reference Kinder, Carnethon, Palaniappan, King and Fortmann39, Reference Goldbacher, Bromberger and Matthews40], current depression represented by an Inventory of Depression Symptomatology (IDS) score above 11 (n=398) [Reference Rush, Gullion, Basco, Jarrett and Trivedi41, Reference Ringen, Engh, Birkenaes, Dieset and Andreassen42], current elevated mood represented by a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score above 8 (n=223) Reference Young, Biggs, Ziegler and Meyer[43], current Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) score (n=28), hours of exercise per week (n=232), intake of alcohol during the last two weeks (n=69) and daily smoking (n=59). The adjusted analyses also included adjustment for olanzapine, quetiapine or risperidone (those two that were not the exposure variable) and their interaction with SSRI, and in addition clozapine, first generation high potency antipsychotics (perphenazine, haloperidol, flupentixol, zuclopenthixol), first generation low potency antipsychotics (levomepromazine, chlorpromazine, chlorprothixene), lithium, and weight-inducing mood stabilizers (valproic acid and gabapentin) [Reference Hasnain and Vieweg44, Reference Hasnain, Vieweg and Hollett45].

Two-sided P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported where relevant. Analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 (IBM, Chicago, IL).

3 Results

3.1 Participants characteristics

Of the 1301 patients included in the study, a total of 280 (21.5%) (169 with schizophrenia and 111 with bipolar disorder) used an SSRI. The SSRIs used were escitalopram (n=154), citalopram (n=51), sertraline (n=40), fluoxetine (n=25), paroxetine (n=8), escitalopram and citalopram (n=1) and escitalopram and sertraline (n=1). The specific indications for SSRI treatment were not stated. The proportion of SSRI users among patients treated with olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone was 76/398 (19.1%), 64/238 (27.4%) and 27/128 (21.1%), respectively. Further details of the patient population are presented in Table 1.

3.2 Regression analyses

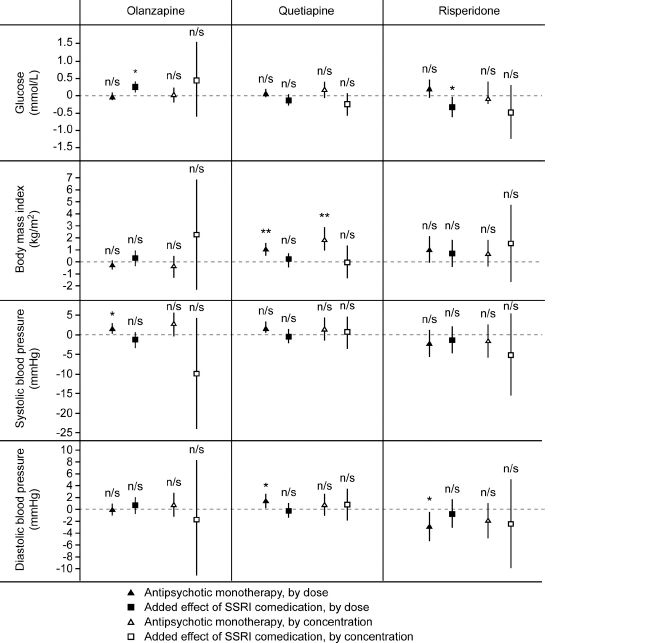

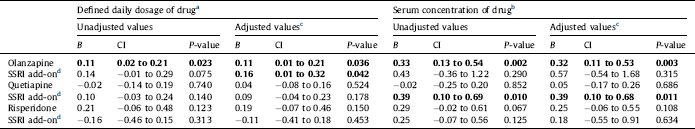

The association of olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone monotherapy as well as the association of SSRI co-medication with the metabolic variables and blood pressure, are displayed in Figs. 1 and 2. Unadjusted and adjusted results for the effect on total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol levels are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

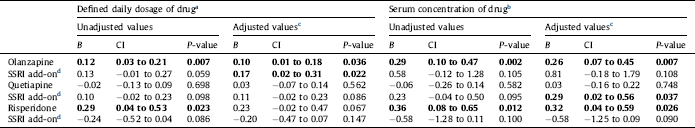

SSRI at a dose of 1 DDD/day in combination with olanzapine was associated with an increase of total cholesterol with 0.16 mmol/L (CI 0.01 to 0.32 mmol/L) after adjustment for all potential confounders. As olanzapine itself was associated with an increase of the cholesterol level with 0.11 mmol/L, the estimated combined effect of both olanzapine and an SSRI would be 0.27 mmol/L. There was also an association between SSRI co-medication with quetiapine and total cholesterol, where an SSRI reference serum concentration was associated with an increase of 0.39 mmol/L (CI 0.10 to 0.68 mmol/L) in total cholesterol. No significant association with total cholesterol was seen for an SSRI combined with risperidone (Fig. 1, Table 2).

For LDL-cholesterol, SSRI at a dose of 1 DDD/day combined with olanzapine was associated with an increase in LDL-cholesterol of 0.17 mmol/L (CI 0.02 to 0.31 mmol/L), with an estimated total effect of both olanzapine (at a dose of 10 mg/d) and an SSRI of 0.27 mmol/L after adjustment for all potential confounders. When combining an SSRI and quetiapine, there was an association between a reference serum concentration of the SSRI and an increase of the serum level of LDL-cholesterol with a mean of 0.29 mmol/L (CI 0.02 to 0.56 mmol/L). No significant association with LDL-cholesterol was seen for SSRI in combination with risperidone (Fig. 1, Table 3).

Fig. 1 Effects on serum total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations of add-on treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. *P≤0.05; **P≤0.01; n/s not significant. HDL: high density lipoprotein; LDL: low density lipoprotein.

Fig. 2 Effects on serum glucose concentration, body mass index and systolic and diastolic blood pressure of add-on treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. *P≤0.05; **P≤0.01; n/s not significant.

For HDL-cholesterol and triglyceride levels, no significant additional effects were seen for SSRI co-medication after adjustment for all potential confounders (Fig. 1, Suppl. Tables A and B). SSRI at a dose of 1 DDD/day was associated with an increase in the glucose concentration of 0.25 mmol/L (CI 0.09 to 0.41 mmol/L) when combined with olanzapine, but with a decrease in the glucose concentration with a mean of 0.32 mmol/L (CI 0.02 to 0.62 mmol/L) when combined with risperidone (Fig. 2, Suppl. Table C). SSRI co-therapy had no significant effects on BMI, systolic blood pressure or diastolic blood pressure (Fig. 2, Suppl. Tables D–F).

4 Discussion

In this naturalistic study of patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder we found statistically significant associations between SSRI and metabolic risk factors when combined with the antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone. The associations were most prominent for total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol when an SSRI was combined with olanzapine and quetiapine. There was also an increase in the glucose levels when combining an SSRI to olanzapine. The effects of using olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone alone were generally the same as in several previous studies using randomized designs, as reported in systematic reviews and meta-analyses [Reference Rummel-Kluge, Komossa, Schwarz, Hunger, Schmid and Lobos9, Reference De Hert, Detraux, Van Winkel, Yu and Correll46, Reference Citrome, Holt, Walker and Hoffmann47]. We nevertheless included the effect of antipsychotics alone to study the SSRI effects in perspective.

Table 2 Effects on total serum cholesterol concentration (in mmol/L) of the antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine or risperidone alone, and effect of add-on treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), in 1301 patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Linear regression analyses were performed with the antipsychotic, the SSRI, and their interaction as covariates. Regression coefficient B for the antipsychotic alone and for the additional effect of the SSRI for a person who uses the antipsychotic, 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P-values are shown. Statistically significant values are displayed in bold.

a The calculated effect is that represented by a daily dose of 10 mg olanzapine, 400 mg quetiapine, 5 mg risperidone or 2.7 mg risperidone for intramuscular depot injection, 10 mg escitalopram, 20 mg citalopram, 20 mg fluoxetine, 20 mg paroxetine or 50 mg sertraline.

b The calculated effect is that represented by a serum drug concentration in the middle of the reference interval for each drug. For details, see Section 2.

c Adjusted for all potential confounders. For details, see Section 2.

d Effect of adding an SSRI to the antipsychotic drug specified in the line above. The effect shown is the combined effect of the SSRI itself and the interaction between the SSRI and the specific antipsychotic drug.

Table 3 Effects on LDL cholesterol concentration (in mmol/L) of the antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine or risperidone alone, and effect of add-on treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), in 1301 patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Linear regression analyses were performed with the antipsychotic, the SSRI, and their interaction as covariates. Regression coefficient B for the antipsychotic alone and for the additional effect of the SSRI for a person who uses the antipsychotic, 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P-values are shown. Statistically significant values are displayed in bold.

a The calculated effect is that represented by a serum drug concentration in the middle of the reference interval for each drug. For details, see Section 2.

b The calculated effect is that represented by a daily dose of 10 mg olanzapine, 400 mg quetiapine, 5 mg risperidone or 2.7 mg for risperidone intramuscular depot injection, 10 mg escitalopram, 20 mg citalopram, 20 mg fluoxetine, 20 mg paroxetine or 50 mg sertraline.

c Adjusted for all potential confounders. For details, see Section 2.

d Effect of adding an SSRI to the antipsychotic drug specified in the line above. The effect shown is the combined effect of the SSRI itself and the interaction between the SSRI and the specific antipsychotic drug.

Our SSRI results are to some extent consistent with previous findings in studies investigating the metabolic effects of combining SSRIs and antipsychotics [Reference Trivedi, Thase, Osuntokun, Henley, Case and Watson22–Reference Hedenmalm, Hagg, Stahl, Mortimer and Spigset29]. The main finding in the present study, that SSRI in combination with olanzapine is associated with a further increase in the total cholesterol level, is in line with the results in the largest previous study, the pooled analysis by Trivedi et al. Reference Trivedi, Thase, Osuntokun, Henley, Case and Watson[22]. They found an increase in total cholesterol of 0.32 mmol/L when combining fluoxetine and olanzapine, in addition to increases of 0.06 mmol/L with fluoxetine monotherapy and 0.08 mmol/L with olanzapine monotherapy. In the present study the estimated combined effect was 0.27 mmol/L and the olanzapine monotherapy effect was 0.11 mmol/L.

The effect of SSRI on LDL-cholesterol when used in combination with antipsychotics has only been investigated in one previous study Reference Tamayo, Sutton, Mattei, Diaz, Jamal and Vieta[28]. In contrast to our results, this study found no significant difference between olanzapine only and the combination olanzapine plus fluoxetine. This discrepancy could both be due to methodological differences between the randomized controlled study and this cross sectional study, and be caused by the fact that fluoxetine has been suggested to be the SSRI with the lowest potential for unfavorable effects on cardiovascular risk factors Reference Beyazyüz, Albayrak, Eğilmez, Albayrak and Beyazyüz[48]. The lack of influence on triglyceride levels by adding an SSRI to an antipsychotic in the present study is consistent with previous findings [Reference Thase, Corya, Osuntokun, Case, Henley and Sanger23, Reference Tamayo, Sutton, Mattei, Diaz, Jamal and Vieta28].

There is conflicting previous evidence with regards to the effect of combining an SSRI with an antipsychotic on the glucose levels. In three previous studies comparing olanzapine only and olanzapine plus fluoxetine, the glucose levels did not differ significantly, although the increases were numerically larger in the combination group [Reference Thase, Corya, Osuntokun, Case, Henley and Sanger23, Reference Shelton, Williamson, Corya, Sanger, Van Campen and Case26, Reference Tohen, Vieta, Calabrese, Ketter, Sachs and Bowden27]. The WHO database study identified SSRI as a risk factor for glucose intolerance when administered in combination with clozapine, olanzapine or risperidone Reference Hedenmalm, Hagg, Stahl, Mortimer and Spigset[29]. We found a statistically significant positive association between SSRI combination with olanzapine and the glucose levels. There was no association with SSRI in combination with quetiapine, and a significant negative association on glucose levels was revealed when combining an SSRI with risperidone. These differential effects can hardly be explained by underlying pharmacological mechanisms, and should most likely be considered as coincidental.

The underlying mechanisms for the aforementioned effects are unknown. A possible mode of action thorough the 5-HT2C receptor could be postulated, as 5-HT2C antagonism is associated with weight gain Reference Chagraoui, Thibaut, Skiba, Thuillez and Bourin[49]. The role of 5-HT2C receptor polymorphisms in body weight gain has been widely studied for antipsychotics Reference Muller and Kennedy[50], but not for the SSRIs. Of the SSRIs, fluoxetine is the only one exerting 5-HT2C receptor antagonistic properties Reference Ni and Miledi[51], whereas the other SSRIs, if anything, possibly might stimulate the 5-HT2C receptor via increased synaptic levels of serotonin. Fluoxetine is however associated with more favorable metabolic outcomes than the other SSRIs Reference Beyazyüz, Albayrak, Eğilmez, Albayrak and Beyazyüz[48]. In our study fluoxetine is very infrequently used, and we consider the influence of the fluoxetine subgroup on the total SSRI effect to be negligible. In animal studies, SSRIs have been shown to affect the hunger hormone ghrelin, but the clinical consequence of these findings remains obscure Reference Fujitsuka, Asakawa, Hayashi, Sameshima, Amitani and Kojima[52].

Risperidone was associated with a decreased diastolic blood pressure. This observed effect is expected as risperidone exerts a potent antagonistic effect on α1-adrenergic receptors, leading to vasodilatation [Reference Schotte, Janssen, Megens and Leysen53–Reference Haller, Makara, Pinter, Gyertyán and Egyed55]. The fact that we were able to reveal this well-known adverse effect in the present material lends credibility to the design and the statistical method applied.

It is of interest to compare the results of the present study with previous findings from our group on the metabolic effects of SSRIs alone Reference Fjukstad, Engum, Lydersen, Dieset, Steen and Andreassen[31]. There, we used a model investigating the isolated effects of SSRI on cardiovascular risk factors, eliminating potentially confounding factors such as any concomitant drug treatment. There were significant associations between dosages and serum concentrations of SSRI and total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol levels, and between SSRI serum concentrations and triglyceride levels Reference Fjukstad, Engum, Lydersen, Dieset, Steen and Andreassen[31]. The effect sizes of SSRI serum concentrations in that study were somewhat larger than in the present study, such as an increase of 0.38 mmol/L for total cholesterol, 0.22 mmol/L for LDL-cholesterol, and 0.52 mmol/L for triglycerides. The effects of SSRI use in combination with antipsychotics in the present study were generally smaller, although we consider these numerical differences being of minor clinical significance.

The present study has some weaknesses that should be addressed. Firstly, the naturalistic and cross-sectional design means that causality cannot be proven and that differences in the metabolic variables compared to pretreatment values were not available. Residual confounding effects caused by e.g. other medical conditions, co-administration of non-psychotropic medications and diet cannot be excluded, even though numerous confounding factors are included in the analyses. Specifically, there was no satisfactory information available on concomitant drug treatment for metabolic and cardiovascular conditions (e.g. use of lipid-lowering, antidiabetic and antihypertensive drugs).

Individuals with the most unfavorable pretreatment metabolic profiles might have been selected for other drug treatment regiments, diets and exercise interventions and in addition not be treated with antipsychotics known to affect the metabolic factors most prominently. This preceding factor could underestimate any difference in the affection of these variables between the antipsychotic drugs.

Finally, as a large number of statistical tests were carried out, there is a risk of false positive associations. Thus, the present findings need to be replicated in independent studies. However, principally all statistically significant results were biologically plausible and in most cases there was congruence between the positive findings.

The present study also has some strengths. First, the risk has been quantified based upon doses and serum concentrations of both the antipsychotics and the SSRIs, instead of applying the conventional dichotomous yes/no exposure variable. The serum concentration would even more closely than the dose be expected to reflect a drug's pharmacological effect at the site of action in the body, as it bypasses both the issues of non-adherence and of interindividual differences in drug disposition. Second, the large number of patients included (n=1301) along with detailed information available for each subject allowed us to adjust for a wide range of potential confounding factors. However, although the total number of subjects is high, the number of patients using the specific drug combinations is considerably smaller. This implies that there could be a risk of type II errors, particularly for the risperidone results.

The SSRI associations with total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol and glucose were, although statistically significant, numerically small. Moreover, in some cases the association was present only when SSRI exposure was expressed in terms of daily dose; in other cases, it was present when the exposure was expressed as the serum concentration of the drug. Taken into account that the results from previously published studies [Reference Trivedi, Thase, Osuntokun, Henley, Case and Watson22–Reference Hedenmalm, Hagg, Stahl, Mortimer and Spigset29] are inconsistent as well, it seems reasonable to conclude that the additional effect by SSRI co-treatment with antipsychotics on cardiovascular risk factors is small. Specifically, if we consider that an SSRI used in combination with olanzapine or quetiapine, increases LDL-cholesterol by 0.15–0.30nmol/l and hypothesize that this causes a corresponding effect (although in the opposite direction) than taking a statin Reference Silverman, Ference, Im, Wiviott, Giugliano and Grundy[56], the relative risk increase of a major cardiovascular event could be estimated to a mere 5–10% (i.e. Fig. 2A in Ref. Reference Silverman, Ference, Im, Wiviott, Giugliano and Grundy[56]). We consider such an increase in cardiovascular risk as being negligible. The importance of monitoring cholesterol, triglyceride and glucose levels as well as body weight in patients using second generation antipsychotics is well documented Reference De Hert, Detraux, Van Winkel, Yu and Correll[46]. This study suggests that a combination of an SSRI and such antipsychotics in a clinical setting most likely does not lead to a further deterioration of metabolic variables to a clinically significant degree. However, thorough metabolic monitoring should be performed when these medications are used in combination, as for antipsychotics used alone.

Disclosure of interest

Dr. Katrine K. Fjukstad, Dr. Anne Engum, Dr. Stian Lydersen, Dr. Ingrid Dieset, Dr. Nils E. Steen and Dr. Olav Spigset declare that they have no competing interest. Dr. Ole A. Andreassen has received speaker honoraria from GSK, Lundbeck and Otsuka, of which only Lundbeck during the last three years.

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author has received a grant to cover salary expenses from AFFU (Department of Research and Development, St Olav University Hospital, P O Box 3008 Lade, NO-7441 Trondheim), Norway. AFFU is a co-organization between St Olav University Hospital and Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). Dr. Håvard Dalen is acknowledged for valuable input regarding the clinical impact of the findings.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.04.001.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.