Introduction

The quality of mental health services plays a central role for the effectiveness and efficiency of mental healthcare systems, symptom reduction, and quality of life improvements on patient level [1]. Thus, a 2012 European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance provided evidence-based recommendations for optimal mental health services in Europe [Reference Gaebel, Becker, Janssen, Munk-Jorgensen, Musalek and Rössler2]. Quality is a multidimensional construct that can be defined according to various components and dimensions (e.g., categories or levels of observation; see [Reference Gaebel, Großimlinghaus, Heun, Janssen, Johnson and Kurimay3]). Quality monitoring, assurance, and improvement assessment in mental healthcare are quickly growing fields of research. Hence, an update of the EPA guidance reflecting the current state of the empirical literature is needed. In this updated EPA guidance, we focus specifically on care coordination in mental healthcare. The aim of care coordination is to provide efficient and patient-centered care across different mental health services and other health services at the interface with the aim to improve health outcomes [Reference Heyeres, McCalman, Tsey and Kinchin4]. A number of models and concepts can be subsumed under the umbrella term “care coordination.” In the scope of this manuscript, we will first briefly describe a selection of concepts in the context of care coordination. The strict differentiation between the various concepts is a rather theoretical approach. In practice, they overlap, and exact boundaries between them cannot be drawn [Reference Lang, Gühne, Riedel-Heller and Becker5]. Next, we present results from a systematic literature review of systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and evidence-based clinical guidelines on care coordination. Based on these results, we then developed recommendations for care coordination in mental healthcare that are graded based on the available evidence.

Care Coordination: Models and Concepts

Care coordination involves the integration of care across the patient’s different needs and conditions during the illness course, across different providers and treatment settings (e.g., inpatient and outpatient care), according to the patient’s capacity and preferences [Reference Pham, O’Malley, Bach, Saiontz-Martinez and Schrag6]. Integrated care is often used synonymously for care coordination and can be described as “the management and delivery of health services so that clients receive a continuum of preventive and curative services, according to their needs over time and across different levels of the health system” [Reference Gröne and Garcia-Barbero7]. Both concepts describe instruments to improve services in relation to access, quality, user satisfaction, and efficiency [Reference Gröne and Garcia-Barbero7].

The reduction of institutionalized care and length of hospital stays has a high priority in models of care coordination [Reference Clibbens, Harrop and Blackett8]. Community-based care is a form of care coordination that adopts a decentralized care pattern to decrease the duration of inpatient care. This concept promotes mental health for local populations including a wide network of support, services, and resources of adequate capacity [Reference Thornicroft, Deb and Henderson9]. Team-based approaches (e.g., home treatment teams or crisis resolution teams) are widely implemented in community-based care concepts to respond to acute mental health difficulties by providing intensive home-based treatment and support. Care coordination across different settings involves the collaboration of various care providers and patients, for example, between mental health specialists and other care providers. Consultation liaison psychiatry, for example, has a strong history in hospital-based care but is becoming increasingly important in primary care settings [Reference Gillies, Buykx, Parker and Hetrick10].

To address the individual coordination of care for certain patient groups, the case management model has emerged [11]. This model aims to integrate care across a variety of health services for individuals with complex needs [Reference Dawson, Lawn, Simpson and Muir-Cochrane12]. Case management implicates a collaborative process that aims to ensure a continuum of care through effective resource coordination [11]. Although there are some variations of this model, all current models of case management include the assignment of a case manager in order to achieve effective care coordination for the patient. Another model that has partly emerged from case management is Intensive Case Management (ICM). This approach contains community-based healthcare services for individuals with severe mental illness who do not require immediate admission [Reference Dieterich, Irving, Bergman, Khokhar, Park and Marshall13]. The caseload in this model is usually smaller, and the intensity of support is higher than in regular case management models [Reference Dieterich, Irving, Bergman, Khokhar, Park and Marshall13]. For more elaborate definitions of types of mental health services, please also refer to the preceding guidance paper [Reference Gaebel, Becker, Janssen, Munk-Jorgensen, Musalek and Rössler2].

Integrated health services depend on the interaction of different care providers. This model requires the accessibility of health services at the local level. However, availability of specialty services might be limited, for example, in rural areas. Therefore, the interest in using digital technology in the provision of health services has considerably increased in recent years. Information and communication technologies can support the remote management of healthcare, for example, by providing self-management tools or enabling electronic communication between service providers and users across distances [14]. Proponents consider the flexibility of digital solutions in mental healthcare as especially suitable for integrated- and community-based care settings and in chronic patients [Reference Adaji and Fortney15]. When implementing coordinated care models, their cost-effectiveness and the assurance of adequate quality of mental health services by measuring quality indicators are also important. Therefore, this meta-review also includes documents that focus on such quality indicators and the cost-effectiveness of care coordination.

The Present Study

The aim of this guidance was to update recommendations regarding care coordination across different mental healthcare services. We systematically reviewed the available evidence from systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and evidence-based clinical guidelines on care coordination in mental healthcare that have been published since the last EPA guidance on the quality of mental health services in Europe [Reference Gaebel, Becker, Janssen, Munk-Jorgensen, Musalek and Rössler2]. Additionally, we developed recommendations based on the available empirical evidence.

Methods

Guidance development

This guidance was developed in accordance with the EPA guidance framework (for details see [Reference Heun and Gaebel16]). The quality of mental health services and care coordination are extensive and multifaceted topics. Thus, we conducted a systematic meta-review (i.e., a systematic overview of meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and evidence-based clinical guidelines) rather than a review of all available primary studies. With this approach, we focus on research that provides high levels of evidence.

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

We conducted a standardized literature search in the databases Medline (PubMed), Scopus, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews applying the search string (“care coordination” OR “case management” OR “integrated care” OR “coordinated care” OR “community based care” OR “home treatment” OR “managed care”) AND (psychiatr* OR “mental”) in titles, abstracts, and keywords in March 2020. We limited study inclusion to systematic review articles, meta-analyses, and evidence-based clinical guidelines. To assure that only studies that were published after the first EPA guidance on the quality of mental health services are included, we set 2011 as the date limit for the inclusion of documents. We applied the following inclusion and exclusion criteria: (a) Studies had to aggregate findings from quantitative investigations of care coordination for persons with mental illness. (b) Studies had to be published in English. (c) Studies focusing on children/adolescents, somatic comorbidity, or a specific mental disorder or symptom (rather than people with mental illness more generally) were excluded.

Study selection and quality assessment

Figure 1 displays the flow diagram depicting the study search and inclusion process. We determined study eligibility in two steps. In the first step, two independent raters (A.K. and J.S.) screened the titles and abstracts of all studies identified in the systematic literature search (n = 587 after removing duplicates) and decided to either exclude or retain the respective article for inspection of the full text (e.g., articles that clearly indicated a focus on children or adolescents in the article title were excluded in this step). In the second step, both raters independently determined study eligibility for the remaining studies (n = 76) based on the full texts. Agreement ([number of consistently coded studies/total number of coded studies] × 100) was 91.1% in Step 1 and 94.7% in Step 2. All disagreements were resolved by consulting the original study manuscripts. Finally, each of the two raters independently excerpted the thematic focus, methods, and main findings for 50% of the included studies. For the respectively coded studies, each rater additionally applied the AMSTAR 2 checklist [Reference Shea, Reeves, Wells, Thuku, Hamel and Moran17]. The AMSTAR 2 checklist is a tool for the critical appraisal of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. Raters evaluate the quality of a systematic review or meta-analysis on 16 items, of which only three apply to meta-analyses. In accordance with prior research, we computed an overall numerical value for each included study by scoring all items whose criteria were fully fulfilled by a study as “1” and all other items as “0.” The maximum possible AMSTAR 2 score for meta-analyses (i.e., 16) is higher than for systematic reviews (i.e., 13). To allow comparison of the AMSTAR 2 scores across studies with different methodologies, we transformed the AMSTAR 2 raw scores to percentages of maximum possible scores (POMP scores [Reference Cohen, Cohen, Aiken and West18]). Next, we rated the grade of evidence for each systematic review, meta-analysis, or evidence-based clinical guideline on a 4-point scale based on the AMSTAR 2 ratings. Table 1 displays the grading system.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the study search and inclusion process.

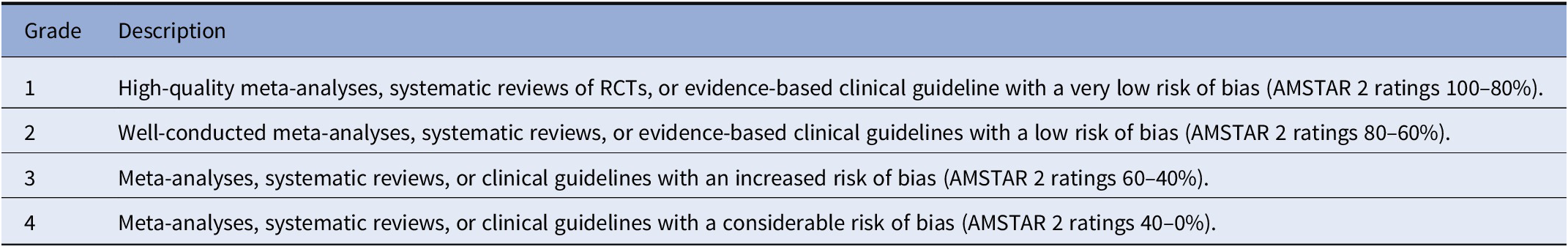

Table 1. Grade of evidence for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Development and grading of recommendations

The topic of this guidance was approved by the EPA guidance committee. We developed the recommendations based on the available evidence in a consensus process involving all authors of this manuscript who represent a substantial proportion of European experts in care coordination. The recommendations were graded on a 4-point scale according to the evidence available to support the respective recommendation (see Table 2).

Table 2. Grading of guidance recommendations (modified from [Reference Stubbs, Vancampfort, Hallgren, Firth, Veronese and Solmi19]).

Results

Study characteristics

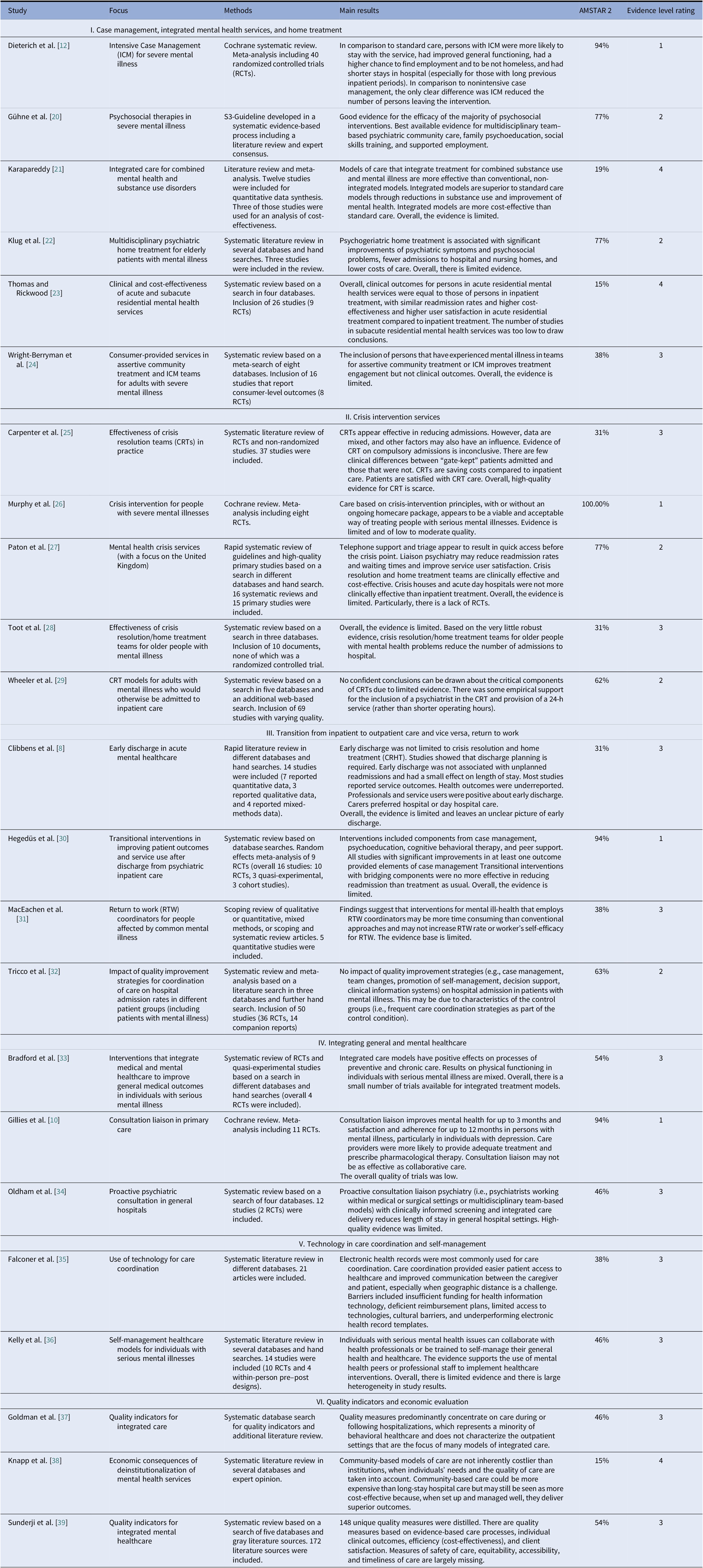

Overall, we identified 23 relevant documents (16 systematic reviews, 6 meta-analyses, and 1 evidence-based clinical guideline). The median publication year was 2015. Table 3 displays the methods, main findings, AMSTAR 2, and evidence-level ratings for all included studies. AMSTAR 2 ratings were relatively low which is, in some cases, due to the thematic focus of the included studies (e.g., randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with control conditions are more difficult to realize for cost-effectiveness analyses than for other interventions in mental healthcare).

Table 3. Focus, methods, main results, and quality ratings of the included studies (n = 23).

We computed a score for AMSTAR 2 by scoring all items whose criteria were fully fulfilled by a study as “1” and all other items as “0” and by transforming the raw scores into percentage of maximum possible scores (POMP scores [Reference Cohen, Cohen, Aiken and West18]).

Study samples included individuals with severe mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia and psychosis, severe mood problems), substance use disorder, anxiety disorder, geriatric patients with mental illness (mood disorders, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, cognitive impairment), individuals with psychosis, bipolar disorder, or self-harm-experiencing mental health crisis. Outcome measures were related to health outcomes, for example, symptom reduction, global functioning, quality of life, or service outcomes, for example, service satisfaction, number of admissions, or costs of care.

Despite some overlap, we have categorized the included studies according to six thematic topics in an inductive process. The studies compare either several components of coordinated care models or focus on one specific coordinated care component: (a) Case management, integrated mental health services, and home treatment, (b) Crisis intervention services, (c) Transition from inpatient to outpatient care and vice versa, return to work, (d) Integrating general and mental healthcare, (e) Technology and self-management in care coordination, and (f) Quality indicators and economic evaluation.

Recommendations

Based on the systematic meta-review of systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and evidence-based clinical guidelines, we developed 15 recommendations for care coordination in mental healthcare services in a consensus process. For comparison with previous recommendations, please refer to Table 1 of the initial EPA Guidance on the Quality of Mental Health Services [Reference Gaebel, Becker, Janssen, Munk-Jorgensen, Musalek and Rössler2].

General recommendations

Recommendation 1. Research programs on mental healthcare services are needed that systematically assess the impact of different models of care coordination on patient-level and healthcare system–level outcomes (recommendation grade D). The majority of systematic reviews and meta-analyses included in this systematic meta-review concluded that the currently available evidence is insufficient to derive definite conclusions. Thus, additional research is needed and should be adequately funded by the relevant national and international funding bodies.

Case management, integrated care, and home treatment

Recommendation 2. Implement Intensive Case Management for people with severe mental illness who are high users of inpatient care and difficult to engage or recurrently disengage (recommendation grade B). ICM may lead to shorter inpatient treatment, lower drop-out rates, and improved social functioning in severely mentally ill persons compared to standard care (i.e., simple outpatient appointments) [Reference Dieterich, Irving, Bergman, Khokhar, Park and Marshall13]. Compared to nonintensive case management, intensive case management is associated with lower drop-out rates [Reference Dieterich, Irving, Bergman, Khokhar, Park and Marshall13] (compare [Reference Gaebel, Becker, Janssen, Munk-Jorgensen, Musalek and Rössler2], recommendation 15)” (p. 11) in comparison to standard care for severely mentally ill persons [Reference Gaebel, Becker, Janssen, Munk-Jorgensen, Musalek and Rössler2]. The recommendation is confirmed based on an update of the review and meta-analysis of Dieterich et al. ([Reference Dieterich, Irving, Park and Marshall40]; compare [Reference Gaebel, Becker, Janssen, Munk-Jorgensen, Musalek and Rössler2], recommendation 15).

Recommendation 3. Implement multidisciplinary team–based psychiatric community care (recommendation grade B). There is good evidence for the effectiveness of psychiatric community care for improving various outcomes [Reference Gühne U, Weinmann, Arnold K, Becker and Riedel-Heller20]. Teams for community or home-based treatment should be multidisciplinary, comprising psychiatric, psychological, and other members of the mental health work force (e.g., nursing staff). Based on updated research, the recommendations to develop a system of community mental health teams (compare [Reference Gaebel, Becker, Janssen, Munk-Jorgensen, Musalek and Rössler2], recommendation 14) and to assemble multiprofessional teams in service provision are confirmed (compare [Reference Gaebel, Becker, Janssen, Munk-Jorgensen, Musalek and Rössler2], recommendation 4).

Recommendation 4. Include persons who have experienced mental illness in teams for community-based treatment for persons with severe mental illness (recommendation grade D). Although the inclusion of persons who have experienced mental illness in teams for community-based treatment does not improve clinical outcomes, it may increase treatment engagement in persons with severe mental illness [Reference Wright-Berryman, McGuire and Salyers24].

Recommendation 5. Offer integrated care for persons with combined mental health and substance use disorders (recommendation grade C). Integrated models of care are more cost-effective and more effective in reducing substance abuse and improving mental health in persons with combined mental health and substance use disorders than conventional, nonintegrated models [Reference Karapareddy21]. This recommendation also builds on a previous recommendation to implement integrated care (compare [Reference Gaebel, Becker, Janssen, Munk-Jorgensen, Musalek and Rössler2], recommendation 16).

Recommendation 6. Provide multidisciplinary psychogeriatric home treatment for elderly persons with mental illness (recommendation grade C). Psychogeriatric home treatment is associated with significant improvements in psychiatric symptoms and psychosocial problems, fewer admissions to hospital and nursing homes, and lower costs of care compared to care as usual [Reference Klug, Gallunder, Hermann, Singer and Schulter22]. Due to the increased somatic comorbidity in elderly persons with mental illness, psychogeriatric home treatment teams should involve medical experts.

Crisis intervention services

Recommendation 7. Offer acute and subacute residential mental health services as an alternative to inpatient treatment for patients whose mental condition does not necessarily require inpatient treatment (recommendation grade C). Clinical outcomes (including readmission rates) do not seem to differ significantly between persons with mental illness in residential treatment and hospital inpatient treatment, but residential treatment is associated with higher cost-effectiveness. Additionally, user satisfaction is higher in acute residential treatment compared to inpatient treatment [Reference Thomas and Rickwood23].

Recommendation 8. Implement crisis intervention teams for people with mental illness in home and community treatment (recommendation grade B). Crisis intervention teams (or crisis resolution teams) are a viable and cost-effective alternative to inpatient treatment [Reference Carpenter, Falkenburg, White and Tracy25,Reference Murphy, Irving, Adams and Waqar26,Reference Paton, Wright, Ayre, Dare, Johnson and Lloyd-Evans27] that may reduce admission rates [Reference Carpenter, Falkenburg, White and Tracy25,Reference Murphy, Irving, Adams and Waqar26] and waiting times and increase service user satisfaction [Reference Paton, Wright, Ayre, Dare, Johnson and Lloyd-Evans27]. Crisis intervention teams were also considered effective components of home treatment previously (compare [Reference Gaebel, Becker, Janssen, Munk-Jorgensen, Musalek and Rössler2], recommendation 27).

Recommendation 9. Offer crisis interventions teams as a 24 h-service and include a psychiatrist in crisis intervention teams in mental healthcare (recommendation grade C).

Although evidence is rater limited, operating crisis resolution teams as 24-h services (rather than shorter operating hours) and including a psychiatrist in crisis resolution teams seem to be associated with increased effectiveness [Reference Wheeler, Lloyd-Evans, Churchard, Fitzgerald, Fullarton and Mosse29].

Transition from inpatient to outpatient care and vice versa

Recommendation 10. Provide elements of case management to persons with mental illness after discharge from inpatient treatment (recommendation grade C). Overall, a systematic review found no positive effect of transitional interventions on readmission rates compared to treatment as usual. Yet, there was some limited evidence that elements of case management (e.g., transition managers and timely communication between inpatient staff and outpatient care) may have positive effects on health-related and social outcomes (e.g., symptom severity, quality of life). Additionally, service users prefer transitional interventions [Reference Hegedüs, Kozel, Richter and Behrens30].

Integrating general and mental healthcare

Recommendation 11. Implement consultation liaison psychiatry in primary healthcare (recommendation grade B). Psychiatric consultation liaison services in primary healthcare improve mental health for up to 3 months and satisfaction and adherence for up to 12 months in persons with mental illness. This effect is particularly strong for persons with depression [Reference Gillies, Buykx, Parker and Hetrick10]. Additionally, proactive consultation liaison psychiatry (i.e., psychiatrists working in medical or surgical hospital settings or multidisciplinary team–based models) with clinically informed screening and integrated care delivery reduce length of stay in general hospital settings [Reference Oldham, Chahal and Lee34]. Consultation liaison psychiatry should be implemented in both inpatient and outpatient medical healthcare.

Recommendation 12. Offer integrated care models for persons with mental illness to improve general medical outcomes (recommendation grade C). Incorporating medical preventive and chronic disease care in mental healthcare improves rates of immunization and screening for medical disorders accompanied by positive effects on physical health [Reference Bradford, Cunningham, Slubicki, McDuffie, Kilbourne and Nagi33].

Technology in care coordination and self-management

Recommendation 13. Use digital technology such as electronic health records to enhance care coordination (recommendation grade C/D). Care coordination with electronic health records provides easier patient access to healthcare and improves communication between the caregiver and patient [Reference Falconer, Kho and Docherty35]. Sufficient funding, reimbursement, and access to technologies must be secured.

Recommendation 14. Provide persons with severe mental illness with trainings to efficiently self-manage their general health and healthcare (recommendation grade C). There is some evidence that mental health professionals or peers (i.e., persons with a history of mental illness) may efficiently provide self-management training (e.g., comprising action planning) that improves general health outcomes in persons with severe mental illness [Reference Kelly, Fenwick, Barr, Cohen and Brekke36]. These interventions should be offered as a supplement to existing models of care.

Quality indicators and economic evaluation

Recommendation 15. Systematically develop and implement quality indicators for integrated care models across mental health services (recommendation grade D). There are various quality indicators for integrated care models in mental healthcare, particularly for evidence-based care processes, individual clinical outcomes, efficiency (cost-effectiveness), and client satisfaction [Reference Knapp, Beecham, McDaid, Matosevic and Smith38]. However, quality indicators assessing safety of care, equitability, accessibility, and timeliness of care [Reference Sunderji, Ion, Ghavam-Rassoul and Abate39], as well as quality indicators that focus on outpatient settings as provided by models of integrated care [Reference Goldman, Spaeth-Rublee, Nowels, Ramanuj and Pincus37] are largely lacking. We consider suggestions for quality indicators from the preceding guidance paper [Reference Gaebel, Becker, Janssen, Munk-Jorgensen, Musalek and Rössler2] as valid.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this meta-review, we summarized systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and evidence-based clinical guidelines on models of care coordination for persons with mental illness. Although we identified a substantial number of relevant documents, evidence was weak in that most included systematic reviews and meta-analyses concluded that findings from the available primary studies were insufficient to draw definitive conclusions. A lack of robust evidence had also been identified in the previous guidance, which explains why the recommendations were based mainly on expert opinion [Reference Gaebel, Becker, Janssen, Munk-Jorgensen, Musalek and Rössler2]. In this update of the initial EPA guidance, stronger evidence was available for some but not for all aspects of integrated care. Thus, future research is needed that disentangles the unique and interactive effects of the various components of integrated care. To further improve the evidence base for integrated care, we urgently recommend empirical monitoring and evaluation of the various care coordination projects in mental healthcare that will be implemented in the coming years in Europe and elsewhere.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.