Introduction

Psychotic disorders can be debilitating [Reference Nielsen, Uggerby, Jensen and McGrath1] and is costly [Reference Salomon, Vos, Hogan, Gagnon, Naghavi and Mokdad2]. Their international incidence is 21.4 per 100,000 person years [Reference Jongsma, Gayer-Anderson, Lasalvia, Quattrone, Mulè and Szöke3]. Outcomes for patients and families are poor [Reference Jääskeläinen, Juola, Hirvonen, McGrath, Saha and Isohanni4]. First episode psychosis (FEP) may adversely affect individuals’ educational, employment, and social development through the accumulation of impairment and disability. Greater durations of untreated psychosis (DUP) are moderately associated with worsened prognosis [Reference Marshall, Lewis, Lockwood, Drake, Jones and Croudace5]. Early intervention in psychosis (EIP) is associated with positive effects on clinical and functional status at 5-year follow-up in FEP [Reference Larsen, Melle, Auestad, Haahr, Joa and Johannessen6], although there are gaps in treatment access [Reference Demyttenaere, Bruffaerts, Posada-Villa, Gasquet, Kovess and Lepine7].

EIP services detect and treat psychotic symptoms early to help stem symptoms and associated behavioral and psychosocial problems. Fidelity scales list objective criteria by which EIP programs can be judged to adhere to sets of standards [Reference Addington, Norman, Bond, Sale, Melton, McKenzie and Wang8]. Common characteristics of EIP for FEP include early detection, small patient-to-staff ratios, antipsychotic prescription and monitoring, provision of psychosocial and behavioral treatments, 1–3 years program duration, explicit admission criteria and defined missions to serve specific geographic populations. Not all EIP services look the same, but most share some characteristics described in published standards and fidelity scales.

As the EIP evidence base has grown, relatively well-developed services have been implemented in England, Canada, Australia, and Scandinavia. A survey of 29 European Psychiatric member countries reported most countries had 1–5 EIP or early detection services, with 1–2 sites in 38.9% of evaluated countries. Of the 16 countries providing data, duration of services was 15.5 years, with Germany having the longest service duration [Reference Maric, Petrovic, Raballo, Rojnic-Kuzman, Klosterkötter and Riecher-Rössler9]. Implementation is not widespread, and services are “not yet a broadly accepted or consistent feature of care in most developed countries” [Reference Addington10]. In 2008, the US RAISE program was launched, and within a decade was expected to lead to the establishment of 100 EIP teams [Reference Csillag, Nordentoft, Mizuno, McDaid, Arango and Smith11], yet large-scale implementation has not occurred [Reference McGorry12]. Implementation is piecemeal and momentum slow [Reference McGorry, Ratheesh and O’Donoghue13].

The implementation gap may be partly due to difficulties in embedding multi-component services within healthcare systems without universal healthcare [Reference Hardy, Moore, Rose, Bennett, Jackson-Lane and Gause14] and higher start-up costs compared with treatment-as-usual. Within Psychiatry, there are debates about EIP’s value, where EIP was viewed as a resource and skill diversion from mainstream services, led by “self-confessed evangelists” [Reference Pelosi and Birchwood15]. While early intervention is a familiar medical concept, it is novel in mental health services [Reference McGorry, Ratheesh and O’Donoghue13]. Equivalency in mental and physical health financing is rare, and services for severe mental illness are subject to political disinterest and stigma [Reference Millard and Wessely16]. Given this broader context, we hypothesized that implementation success would be linked to the strength, resilience and financing of the existing health and mental healthcare system.

There are likely other implementation challenges. Implementation science attempts to promote the uptake of research findings in real-world settings [Reference Eccles and Mittman17]. Common implementation outcomes include assessment of the adoption of, fidelity to and sustainability of a service or intervention, rather than the intervention’s outcomes [Reference Best, Greenhalgh, Lewis, Saul, Carroll and Bitz18]. This approach has been successfully applied examine components of complex health systems, for example, research on improving rates of thrombolysis in acute stroke found rates improve with urban location, centralized service models, treatment by neurologists, admission via ambulance, and stroke-specific protocols [Reference Paul, Ryan, Rose, Attia, Kerr and Koller19]. A better understanding of these kinds of contextual and human factors, drawn from existing EIP implementation literature, could assist commissioners, policymakers and clinicians in service development. To the best of our knowledge, there are two descriptive reviews [Reference Csillag, Nordentoft, Mizuno, McDaid, Arango and Smith11,Reference McDaid, Park, Iemmi, Adelaja and Knapp20] on the broad status of EIP service implementation, but no systematic review has collated evidence from existing studies on the barriers and facilitators to EIP implementation. Against this background, the current systematic review and narrative synthesis aims to identify the barriers and facilitators to EIP service implementation.

Methods

A systematic review collated evidence from previous studies of EIP implementation, in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman21]. This method was then combined with a narrative synthesis grounded in guidelines developed by Popay et al. [Reference Popay, Roberts, Snowden, Petticrew, Arai, Rodgers, Britten, Roen and Duffy22] to identify and explore the barriers and facilitators of EIP service implementation.

Registration

This systematic review is registered on PROSPERO (reg no.: CRD42021241603).

Search strategy

A search strategy was developed with a medical librarian for EMBASE, Medline, Web of Science and PsychINFO databases and conducted between June to August 2020 and again in January 2021. Results were limited to articles published up until January 2021. See “Supplementary Materials” for search strategies applied. Duplicated studies were removed. A secondary hand search of references was performed to identify additional relevant papers in the field.

Eligibility criteria

This review sought studies reporting data on barriers and facilitators to EIP implementation. Table 1 presents inclusion and exclusion criteria. A study was eligible if it included information on the implementation of EIP services in any jurisdiction at any time. We did not include services for patients with only prodromal symptoms, those with an at-risk mental state only, or high risk or ultra-high risk psychosis only. Studies recording only patient outcomes were excluded, as well as studies which assessed specific EIP service components only (e.g., psychotherapy alone) and which contained no information on service implementation as a whole.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria applied.

Abbreviations: EIP; early intervention in psychosis; FEP, first episode psychosis.

Study selection process

Study eligibility was assessed by two authors (L.Z. and D.M.) using Covidence software. L.Z. and D.M. independently screened all titles and abstracts. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, and where necessary, involved a third author (N.O.C.) until consensus was reached. Articles’ full texts were screened by two authors (L.Z. and D.M.) and again, discrepancies were resolved through discussion, and where necessary through involvement by N.O.C. The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) displays search, screening, and selection results.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of study selection process.

Data extraction

NOC performed data extraction using an Excel data extraction form specifically designed for this review. The following quantitative and qualitative information were extracted: (a) studies: authors’ name, year of publication, study country, aims, and methods; (b) participants: participant number and type; (c) EIP services: number and type of sites sampled, type of services, and barriers and facilitators to EIP implementation. To extract data on barriers and facilitators, we generated a data abstraction matrix to organize and display content, an approach developed previously by Geerligs et al. [Reference Geerligs, Rankin, Shepherd and Butow23].

Data analysis

The narrative synthesis procedure was derived from Braun and Clarke’s [Reference Braun and Clarke24] thematic analysis approach, a technique successfully applied in previous synthesizes of health system barriers and facilitators [Reference Geerligs, Rankin, Shepherd and Butow23,Reference Cranwell, Polacsek and McCann25]. Data analysis was completed in the following stages: (a) reviewing included articles; (b) deriving codes and subcodes that reflected key concepts within the data; (c) developing these concepts into an overarching thematic framework of categories; (d) indexing each article according to the framework and entering summary data into the cells of the abstraction matrix. Initial codes were generated by N.O.C. and further refined to ensure clarity. The results section presents a systematic description of the studies identified, followed the narrative which discusses the themes arising from all studies.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment was undertaken using Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [Reference Pluye, Robers, Cargo, Bartlett, O’Cathain, Griffiths, Boardman, Gagnon, Rousseau and Robert26]. MMAT has sound psychometric properties and allows assessment of quantitative descriptive studies, qualitative and mixed methods studies. Eleven studies were descriptive accounts of EIP implementation and beyond the scope of quality assessment [Reference Csillag, Nordentoft, Mizuno, McDaid, Arango and Smith11,Reference Hardy, Moore, Rose, Bennett, Jackson-Lane and Gause14,Reference Baumann, Crespi, Marion-Veyron, Solida, Thonney and Favrod27–Reference Reilly, Newton and Dowling35]. They were retained as they contained important implementation information. The remaining 12 studies were assessed using MMAT by N.O.C. [Reference Cheng, Dewa and Goering36–Reference Luther, Bonfils and Salyers47]. A subset (n = 5) were reviewed by a second author (C.D.) to assess agreement. Agreement was defined as the proportion of items where both raters gave a positive (yes) or a negative (cannot tell, no) score. Agreement analysis was based on Cohen’s Kappa for inter-rater reliability. Scores varied between 0.6 and 1.0, with a total score of 0.8, indicating substantial agreement. Discrepancies were resolved through iterative discussion.

Results

Systematic review

Included studies

Of 3,964 studies identified, 23 met inclusion criteria. Summary study characteristics and study references are reported in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary information displaying author, year, title, country, methodology, and key barriers and facilitators of included studies.

Abbreviations: EIP; early intervention in psychosis.

Countries of origin

Most studies were based in high-income countries, including the United States (n = 6), England (n = 5), Australia (n = 4), Canada (n = 3), Italy (n = 2), and Switzerland (n = 1). One originated in Central and Eastern Europe (n = 1), while one included descriptive information from services across the world.

Methods

A variety of methodologies were employed, including descriptions of EIP implementation (n = 8), qualitative (n = 3), survey (n = 3), mixed methods studies (n = 3), narrative reviews (n = 2), audits (n = 2), a case study and one feasibility study. See Table 2 for a full list of study methodologies.

Participants and study sites

Studies employed a variety of participant groups to assess views and experiences of implementation. In 11, there was no direct sampling of any participant group. Instead, the papers comprised authors’ own descriptions or reviews of service or program implementations. In three, patients were directly sampled and in two, participants were EIP clinicians. In the remaining six, participants were described as representatives of services, EIP professional experts, senior EIP program decision makers, program leads, a mixed sample of patients, families, and clinicians, or there was no description of participant type.

In six studies, there was no sampling of specific EIP sites. Of the remaining 17, the mean number of sites sampled was 31 (range: 1–152), with 8 sampling only 1 site. Ghio et al. surveyed 152 mental health centers in Italy, Tiffin et al. sampled 118 teams supported by 53 National Health Service (NHS) Trusts, and Pinfold et al. sampled 117 EIP teams using a self-report audit tool in eight English regional development centers.

EIP services

A variety of service models were included in studies. In 12, the authors presented macro-level details from either a variety of EIP services across international countries, across countries within a region, or across regions within a country. In the remaining 11, information on individual services and their components was available (Table 3). These studies include a variety of service models, including hub and spoke models [Reference Brabban and Dodgson28,Reference Cocchi, Balbi, Corlito, Ditta, Di Munzio and Nicotera37], standalone teams [Reference Baumann, Crespi, Marion-Veyron, Solida, Thonney and Favrod27,Reference Hetrick, O’Connor, Stavely, Hughes, Pennell and Killackey30–Reference Kelly, Wellman and Sin32,Reference North, Simic and Burruss44], or services that focused on collaborative partnerships [Reference Hardy, Moore, Rose, Bennett, Jackson-Lane and Gause14,Reference Gidugu, Rogers, Gordon, Elwy and Drainoni40,Reference Beiser, Erickson, Fleming and Iacono50]. Each offered early intervention, a range of psychosocial services, psychiatric and medication reviews and often some form of assertive case management.

Table 3. Information on individual EIP services and their key components.

Abbreviations: EIP; early intervention in psychosis; FEP, first episode psychosis.

Narrative synthesis

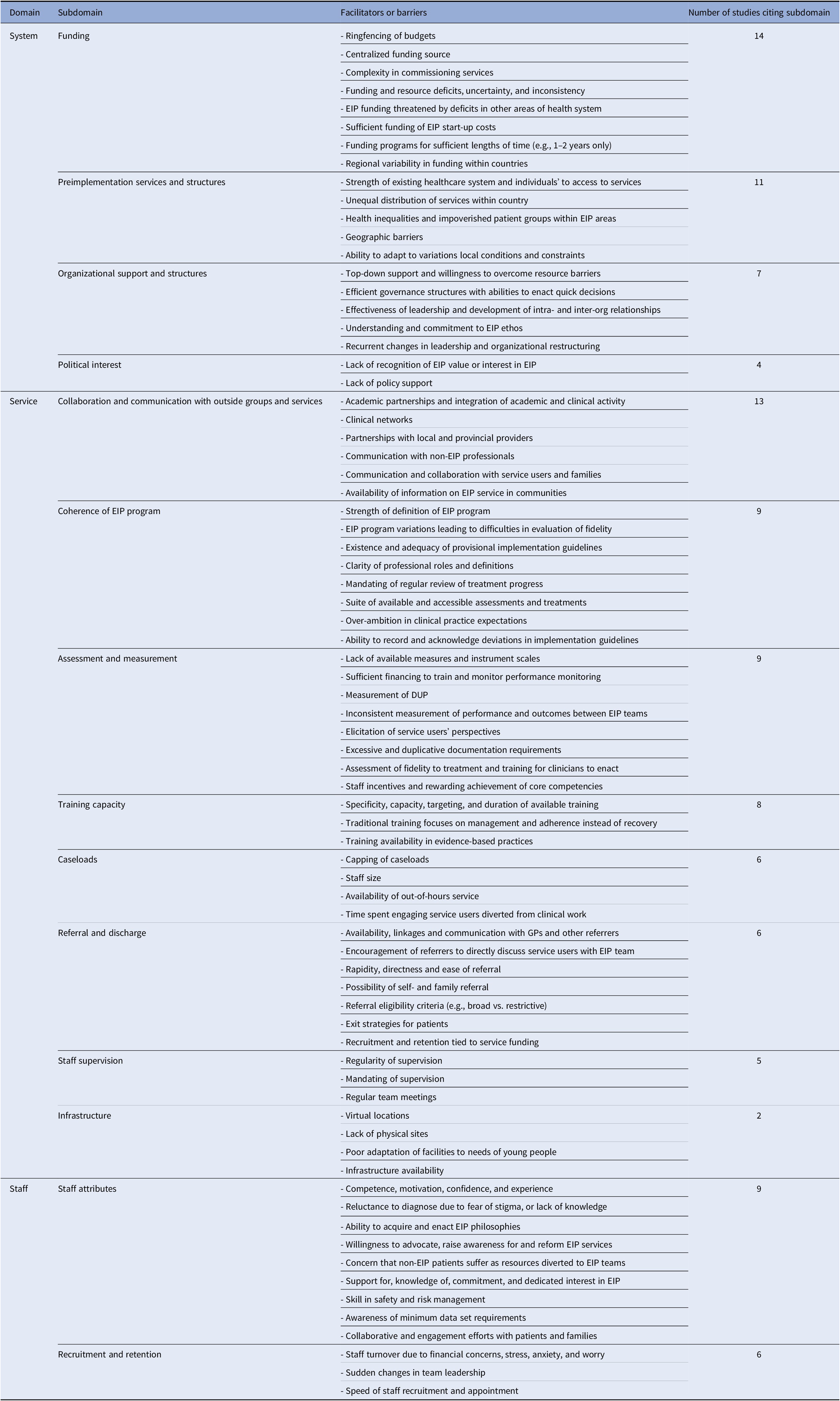

Narrative synthesis identified three domains: (a) system; (b) service; and (c) staff, with 14 associated subdomains. Domains and subdomains are described in Table 4, and Table 2 outlines each barrier and facilitator identified in each study.

Table 4. Identified barriers and facilitators of EIP service implementation.

Abbreviations: EIP; early intervention in psychosis.

System barriers and facilitators

Funding

The most commonly cited barrier was insufficient funding (cited in 14 studies [Reference Csillag, Nordentoft, Mizuno, McDaid, Arango and Smith11,Reference Baumann, Crespi, Marion-Veyron, Solida, Thonney and Favrod27,Reference McGorry and Yung33,Reference Cocchi, Balbi, Corlito, Ditta, Di Munzio and Nicotera37,Reference Lester, Birchwood, Bryan, England, Rogers and Sirvastava42,Reference Maric, Andric Petrovic, Rojnic-Kuzman and Riecher-Rössler43]). Under-resourcing of programs led to insufficient time and scope for staff training, prioritization of clinical work over community development and outreach [Reference Durbin, Selick, Hierlihy, Moss and Cheng38], insufficient staffing [Reference Maric, Andric Petrovic, Rojnic-Kuzman and Riecher-Rössler43], and financial concerns amongst staff [Reference Powell, Hinger, Marshall-Lee, Miller-Roberts and Phillips34]. Program funding models within countries varied [Reference Powell, Hinger, Marshall-Lee, Miller-Roberts and Phillips34,Reference Durbin, Selick, Hierlihy, Moss and Cheng38]. In the United States, private insurer models existed rather than centralized financing [Reference Powell, Hinger, Marshall-Lee, Miller-Roberts and Phillips34]. This threatened service sustainability as insurers required the demonstration of treatment indication, reimbursing direct clinical care only, and requiring programs to operate without financial loss [Reference Powell, Hinger, Marshall-Lee, Miller-Roberts and Phillips34].

Services were often guaranteed future spending dependent upon achieving specific outcomes. In the United States and England, funding continuation depended on the number of engaged patients [Reference North, Simic and Burruss44] or the meeting of caseload targets [Reference Lester, Birchwood, Bryan, England, Rogers and Sirvastava42]. Teams often struggled to recruit and retain patients in their first year and staff responded by restricting age eligibility criteria, discharging patients early, or imposing waiting lists [Reference Lester, Birchwood, Bryan, England, Rogers and Sirvastava42].

Complex service commissioning systems were reported in England, where a single EIP team negotiated with numerous Primary Care Trusts [Reference Tiffin and Glover46]. EIP commissioners reported recurrent organizational restructuring as an impediment to partnership-building across health and social care sectors, mental health as a low priority, and an inability to ring-fence mental health budgets [Reference Lester, Birchwood, Bryan, England, Rogers and Sirvastava42].

Preimplementation services and structures

The strength and availability of existing services affect the ease with which new models can be established. In Italy, EIP diffusion was only 20–30% [Reference Ghio, Natta, Peruzzo, Gotelli, Tibaldi and Ferrannini39], where implementation heterogeneity was a consequence of chronic regional under-investment and local deprivation. Services in regions of high deprivation face greater challenges due to complex housing needs, high unemployment, higher psychosis incidence [Reference Häfner, Riecher-Rössler, Hambrecht, Maurer, Meissner and Schmidtke51], harder-to-reach groups like refugees and asylum seekers, and have fewer opportunities to involve voluntary and community services [Reference Lester, Birchwood, Bryan, England, Rogers and Sirvastava42]. Rural isolation and inaccessibility will likely lead to unequal physician distribution [Reference Durbin, Selick, Hierlihy, Moss and Cheng38].

Low-income countries face the greatest implementation problems, in particular due to a greater historical reliance on institutionalization [Reference Csillag, Nordentoft, Mizuno, McDaid, Arango and Smith11]. In Central and Eastern Europe, mental health expenditure ranged from 1.4 to 8%, and the number of psychiatrists ranged from 1.3 to 13 per 100,000 population [Reference Maric, Andric Petrovic, Rojnic-Kuzman and Riecher-Rössler43]. In Germany, mental health expenditure is 11% and there are 15 psychiatrists per 100,000 population.

Organizational support and structures

Effective leadership and good governance structures facilitate implementation. Regional English EIP ‘champions’ (i.e., teams who developed early) helped guide and instil optimism in under-developed teams [Reference Tiffin and Glover46]. Speedy decision-making and belief in an EIP ethos were regarded as necessary components within governance structures [Reference Lester, Birchwood, Bryan, England, Rogers and Sirvastava42]. A program in San Francisco established executive, operations, evaluation, training, and outreach standing committees, giving each their own charter, scope of competency, membership, chair, meeting schedule and performance metrics. This adoption of an established business model within EIP governance structures could improve service efficacy [Reference Hardy, Moore, Rose, Bennett, Jackson-Lane and Gause14].

Political interest

Political disinterest stymies EIP development. The emergence of strong evidence on EIP effectiveness from the OPUS trial convinced politicians to financially support EIP programs in Denmark [Reference Csillag, Nordentoft, Mizuno, McDaid, Arango and Smith11], but health departments in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Ukraine published mental health strategies referencing EIP, without timeframe commitments [Reference Maric, Andric Petrovic, Rojnic-Kuzman and Riecher-Rössler43]. U.S. state leaders in Maryland and New York recognized research that established the feasibility of EIP teams, a recognition accompanied by funding and promises to expand services within both states [Reference Beiser, Erickson, Fleming and Iacono50]. Political recognition is vital at all levels of government.

Service barriers and facilitators

Collaboration and communication with outside groups and services

Thirteen studies discussed the need for effective collaboration and communication links with other organizations. National and international conferences can foster clinical and academic networks [Reference McGorry and Yung33]. Clinical academics can provide data to help establish programs and outcome monitor [Reference Cheng, Dewa and Goering36], while services improve study recruitment [Reference Baumann, Crespi, Marion-Veyron, Solida, Thonney and Favrod27]. Montreal’s PEPP program used research assessments to help set treatment goals and research was shared with patients [Reference Iyer, Jordan, Macdonald, Joober and Malla31]. Pinfold et al. [Reference Pinfold, Smith and Shiers45] caution however that research is not a substitute for overcoming structural problems like inequitable access and service incapacity and Cheng et al. [Reference Cheng, Dewa and Goering36] reported that provincial Ontario EIP advocacy networks were more influential in service initiation than direction from research.

The importance of service outreach was common across studies with linkages described with schools, employment agencies, child and adolescent psychiatry, drug and alcohol services, primary care, child and youth mental health agencies, youth shelters, housing services, fundraising officials and marketing firms [Reference Csillag, Nordentoft, Mizuno, McDaid, Arango and Smith11,Reference McGorry and Yung33,Reference Cheng, Dewa and Goering36]. Collaborations can increase referrals, improve access to hard-to-reach patients, and raised patient and family satisfaction [Reference Cheng, Dewa and Goering36]. Small teams particularly benefit from such partnerships [Reference Durbin, Selick, Hierlihy, Moss and Cheng38], and allowed patients who did not meet an EIP team’s inclusion criteria to receive appropriate community referrals [Reference Iyer, Jordan, Macdonald, Joober and Malla31].

Coherence of the EIP program

The coherency of the EIP model matters. These models should draw from existing evidence, incorporate workers’ vision and measure fidelity [Reference Csillag, Nordentoft, Mizuno, McDaid, Arango and Smith11]. While fidelity measurement of fidelity is important, tension was noted between creating services derived from gold standards versus adaptations to local contexts. Cheng et al. [Reference Cheng, Dewa and Goering36] reported team leaders’ frustration at a lack of area-specific guidelines, but where local guidelines existed, some clinicians found these too restrictive. Given the clinical and biological variability of psychotic disorders and the likelihood that the course and outcome is affected by regional differences, regional guidelines could prove clinically effective. In an audit of 117 EIP teams in England [Reference Pinfold, Smith and Shiers45], a quarter of teams deviated from the policy implementation guide, but few formally applied for fidelity flexibilities. EIP models can adapt to specific contexts if there is concurrent implementation evaluation [Reference Csillag, Nordentoft, Mizuno, McDaid, Arango and Smith11], and if patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness remain equivalent. Nonetheless, Pinfold et al. [Reference Pinfold, Smith and Shiers45] caution that large deviations within an environment of funding deficits and access inequity may lead to insufficient resourcing, affecting the ability to provide the comprehensive services and eroding the integrity of the original EIP model.

Assessment and measurement

Prospective patient outcome, treatment fidelity and service performance monitoring are important facilitators. Consistency in standardized patient outcomes strengthens the ability to compile evidence on value. Demonstrations of service and treatment fidelity improve future replication efforts.

Measurement issues were described in two studies. Inadequate data collection in Italian EIP teams was linked to a lack of completed or available standardized assessments [Reference Cocchi, Balbi, Corlito, Ditta, Di Munzio and Nicotera37]. An audit of English services found few teams measured DUP and there were inconsistencies in standardized measures [Reference Pinfold, Smith and Shiers45]. Standardized DUP scales include a checklist [Reference Singh, Cooper, Fisher, Tarrant, Lloyd and Banjo52] measuring the emergence of first noticeable symptoms, psychosis and treatment-seeking. The Interview for the Retrospective Assessment of the Onset of Schizophrenia [Reference Essock, Nossel, McNamara, Bennett, Buchanan and Kreyenbuhl53] assesses symptoms and impairment at the onset of emerging psychosis and the Nottingham Onset Schedule [Reference Wisdom, Knapik, Holley, Van Bramer, Sederer and Essock54] defines onset as the time between first reported change in mental state and the development of psychotic symptoms. It allows measurement of treatment delays, duration of untreated illness, and duration of both untreated emergent and untreated manifest psychosis. DUP measurement is varied and complex, for example, DUP end can be defined differently, for instance, the point of antipsychotic prescription, referral to nonpharmacological treatment or if there are affective components, when antidepressants are given. A recognition that inconsistent measurement impedes service continuation, and that conversely, excessive and duplicative documentation burden staff, led an Australian service to develop a clinical pathway integrating outcome measurement into routine documentation procedures [Reference Reilly, Newton and Dowling35]. The San Francisco PREP program trained staff in rigorous data collection, developing an electronic health record that enabled data sharing within teams and with community partners [Reference Hardy, Moore, Rose, Bennett, Jackson-Lane and Gause14].

Service fidelity measurement is expensive but possible using routinely collected, service data [Reference Essock and Kontos29,Reference Essock, Goldman, Hogan, Hepburn, Sederer and Dixon48], where structural (e.g., staffing) and care processes (e.g., presence of completed side-effect checklists) can be assessed [Reference McDonald, Ding, Ker, Dliwayo, Osborn and Wohland49]. Staff reminder prompts improve completion and entry of outcome measures [Reference Hetrick, O’Connor, Stavely, Hughes, Pennell and Killackey30]. Most importantly, a recognition of the value of patient and service monitoring is required, alongside the provision of funding and training [Reference Beiser, Erickson, Fleming and Iacono50].

Training capacity

Training in psychosocial interventions was a facilitator in eight studies. Teams can suffer from high staff turnover [Reference Powell, Hinger, Marshall-Lee, Miller-Roberts and Phillips34] and top-up training can improve retention. In Italy, no specialized training was provided in 26% of 152 teams surveyed [Reference Ghio, Natta, Peruzzo, Gotelli, Tibaldi and Ferrannini39], while in Northumberland [Reference Brabban and Dodgson28], most EIP care coordinators were trained in psychosocial interventions, a fact the authors argue as central to the team’s success.

The opportunity to receive training can attract new staff and a diversity of training perspectives provide more tools with which to assist recovery [Reference Gidugu, Rogers, Gordon, Elwy and Drainoni40]. Training costs should be factored into start-up and expansion financing, but teams can develop partnerships to help cover training costs, for example the US RAISE program collaborated with academics to train staff [Reference Beiser, Erickson, Fleming and Iacono50].

Caseloads

Small caseloads are recommended as the gold standard in EIP delivery. UK EIP guidelines [55] recommend 15 patients per care coordinator. Ontario’s implementation policy did not specify a caseload target and as a result, 25% of programs reported staff caseloads greater than 25 [Reference Durbin, Selick, Hierlihy, Moss and Cheng38]. Higher caseloads can lead to delays in intervention delivery [Reference Brabban and Dodgson28], and limitations on outreach activities which serve to increase referrals [Reference Lester, Birchwood, Bryan, England, Rogers and Sirvastava42]. High caseloads are not universal, however. Of the 118 teams in operation in England in 2006, only one region was served by teams carrying caseloads approaching the target. This was due to an overestimation of rural prevalence, limits on teams’ capacity, and lower-than-expected referral rates [Reference Tiffin and Glover46]. Prevalence estimates are a common planning requirement [56], but Tiffin et al. caution that caseloads are unlikely to be established until teams are in operation for 3 years [Reference Tiffin and Glover46]. A perception that EIP teams carry small caseloads caused tensions with generic community mental health teams who viewed EIP staff as carrying less intensive workloads. Communication between teams ensure staff appreciate each other’s relative strengths [Reference Lester, Birchwood, Bryan, England, Rogers and Sirvastava42].

Referral and discharge

The strength of teams’ referral links improves patients’ rapid access to services. Patients often first have contact with mental health services at crisis point, or may be initially referred to CMHTs, potentially resulting in increased DUP [Reference Birchwood, Connor, Lester, Patterson, Freemantle and Marshall57]. Referrals from large mental health systems are associated with longer DUP, where care pathways may be more complicated [Reference Iyer, Jordan, Macdonald, Joober and Malla31]. Periodical meetings with potential referrers can be effective [Reference Cocchi, Balbi, Corlito, Ditta, Di Munzio and Nicotera37]. Links with local emergency departments prevented hospitalizations and minimized the potentially traumatic effects of encountering care within emergency or inpatient settings [Reference Iyer, Jordan, Macdonald, Joober and Malla31]. Family and self-referral improved service uptake and decreased help-seeking delay [Reference Iyer, Jordan, Macdonald, Joober and Malla31,Reference Cocchi, Balbi, Corlito, Ditta, Di Munzio and Nicotera37]. Reductions in documentation, along with the appointment of trained intake clinicians later involved in treatment, improved access and helped establish engagement [Reference Iyer, Jordan, Macdonald, Joober and Malla31,Reference Kelly, Wellman and Sin32].

Staff supervision

Several issues arose regarding supervision of staff. In the Italian system, the provision of clinical supervision was low, with at most 12.5% of teams offering supervision in northern regions, with no provision in the south. The Australian EPPIC and San Francisco PREP models noted that nonmandating clinical supervision impeded implementation [Reference Hardy, Moore, Rose, Bennett, Jackson-Lane and Gause14,Reference Hetrick, O’Connor, Stavely, Hughes, Pennell and Killackey30]. EPPIC developed a workforce development plan requiring clinical supervision on a minimum fortnightly basis. In a Northumberland EIP service [Reference Brabban and Dodgson28], a clinical psychologist provided supervision to all practitioners, regardless of specialism. Regular supervision for staff in rural regions reduces feelings of isolation [Reference Powell, Hinger, Marshall-Lee, Miller-Roberts and Phillips34], while hub and spoke models led to some confusion as to who was responsible for the supervision of spoke staff embedded within CMHTs [Reference Cheng, Dewa and Goering36].

Infrastructure

In Central and Eastern Europe, the most commonly cited limitation to implementation was inadequate infrastructure, with many services operating within hospital settings [Reference Maric, Andric Petrovic, Rojnic-Kuzman and Riecher-Rössler43]. Staff may lack appropriate facilities within hub and spoke models specifically due to the often virtual operation of hubs. In Northumberland [Reference Brabban and Dodgson28], this impeded attempts to improve patient engagement. As the average EIP patient is often younger than in general mental health services, youth-friendly, low stigma out-patient settings that are easily accessible are vital.

Staff barriers and facilitators

Staff attributes

The skills and competencies required to work within EIP services was described in nine studies. A range of competencies were described: safety and risk management; EIP model knowledge; treatment knowledge; ability to engage with young people; confidence in treatment delivery [Reference Brabban and Dodgson28]; understanding recovery principles [Reference Kelly, Wellman and Sin32]; ability to instil therapeutic optimism; willingness to diagnose; belief in EIP ethos; enacting service change [Reference Hetrick, O’Connor, Stavely, Hughes, Pennell and Killackey30]; creativity in patient engagement [Reference Baumann, Crespi, Marion-Veyron, Solida, Thonney and Favrod27]; and ability to adapt therapies; [Reference Gidugu, Rogers, Gordon, Elwy and Drainoni40]. EIP services often adopt collaborative approaches, focusing on goals, resources and achievements, often a departure from traditional approaches [Reference Kelly, Wellman and Sin32]. Similarly, staff can be expected to share therapeutic roles and responsibilities, regardless of professional background [Reference Lester, Birchwood, Bryan, England, Rogers and Sirvastava42]. This necessitates a willingness to engage in “mundane” tasks, like visiting cinemas or offering lifts.

Recruitment and retention

Issues relating to staff recruitment and retention were discussed in five studies. Powell et al. [Reference Powell, Hinger, Marshall-Lee, Miller-Roberts and Phillips34] reported that recruitment was a major barrier to implementation in the United States, suggesting teams identify the skills that best complement existing team dynamics prior to role-filling. High staff turnover was seen as a concern, particularly in the early months of teams’ existence [Reference North, Simic and Burruss44], leading to disruptions in the establishment of team processes [Reference Reilly, Newton and Dowling35]. Due to under-financing, staff may work beyond capacity for long periods, feel excessive pressure to meet targets, leading to the erosion of morale and good will [Reference Lester, Birchwood, Bryan, England, Rogers and Sirvastava42]. Emotional support, supportive leadership styles and positive work climates are necessary [Reference Powell, Hinger, Marshall-Lee, Miller-Roberts and Phillips34].

Discussion

Main findings

This systematic review and narrative synthesis provides data from 23 studies and identified three over-arching domains that influence implementation: system, service, and staff-level factors, with 14 associated subdomains. There was considerable overlap between subdomains. Barriers and facilitators to implementation were common across many countries and regions.

The most common barrier was funding. This issue played a demonstratable role in many subdomains, for example, the preimplementation landscape, staff training, referral and outreach practices, caseload targets, and the ability to monitor and evaluate services. Funding deficits are likely partly fueled by political disinterest. It is of concern that insufficient budgets, and the indexing of budgets to performance, caused service adaptations without associated evaluation, threats to fidelity and the ability to replicate and “scale-up” services. That budgeting issues underlie so many subdomains also suggests that sufficient funding of EIP services, while not the only antidote, could assist in overcoming many attendant barriers. Funding programs in a post-COVID context may become difficult, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). In LMICs EIP prioritization may be achieved via increased political will, legislative change, better allocation of resources, and organization, increasing the mental health workforce, reducing funding to hospitals while increasing community spending, and greater patient involvement in service design. In Western countries, the same principles apply, coupled with progressive taxation based on income and wealth, and legislating for minimum mental health budgets of at least 15%.

It is a truism that the existing healthcare landscape will significantly influence implementation. The extent of existing staffing levels, governance structures, clinical networks, collaborations, evaluative capacity, and prior investment predict success. The studies in this review did not describe “treatment as usual” prior to EIP implementation, but the barriers identified align with common macro-level barriers in health service reform more generally, such as inertia to change, regulatory challenges, operational complexity, and unclear financial and governance processes [Reference Maruthappu, Hasan and Zeltner58,Reference Darker, Nicolson, Carroll and Barry59]. The symbiotic relationship between and within domains suggests pre-implementation evaluation, using validated measurement, of all aspects of the health system context could aid the development of EIP models [Reference Weiner, Mettert, Dorsey, Nolen, Stanick and Powell60], and better predict the local adaptations necessary.

The system domains are generic to most health and mental health services. Lessons could be drawn from other specialities. Stroke care also emphasizes early intervention and underwent substantial reform in London in 2008 [Reference Morris, Hunter, Ramsay, Boaden, McKevitt and Perry61]. Program leaders wielded significant political power, required rigorous performance measurement to achieve accreditation, and previous system failures led to a focus on implementing small numbers of only essential priorities [Reference Turner, Ramsay, Perry, Boaden, McKevitt and Morris62]. While lessons from other medical specialities necessitating early intervention are useful, EIP barriers and facilitators could also prove useful in other settings. Nonetheless, services for severe mental illnesses face a unique set of challenges [Reference Millard and Wessely16].

Many of the service and staff-level domains were specific to EIP provision, such as the necessitation of strong referral partnerships and collaboration across and between governmental organizations. EIP models require clear supervisory lines of support and training so staff embedded in CMHTs and rural areas do not face isolation. The studies included in this review did not provide specific information on staff training, however such programs exist (e.g., the NHS’s Health Education England elearning course and the OnTrack New York initiative). A future review on their specific components and differences could be useful. The literature highlights a set of unique EIP competencies with staff required to embrace new ways of working, and a fluidity in professional identity. Finally, funding systems must recognize the developmental and outreach aspects of EIP services, alongside the attainment of clinical targets [Reference Lester, Birchwood, Bryan, England, Rogers and Sirvastava42]. Some guarantees of consistent financial support could reduce uncertainty and build trust amongst staff.

Limitations

There are several limitations. We included studies available in English only, likely underrepresenting non-English speaking countries. We included implementation descriptions with no associated methodologies, which precluded quality assessment of all studies. Of studies employing methodologies, much detail on barriers and facilitators was extracted from discussions, although this real-world information is likely a good representation of experience. This review describes findings from healthcare systems where EIP services are implemented which will differ to those where no EIP exists. Few studies included formal assessments of implementation, utilized implementation frameworks or applied fidelity measures, limiting the strength of evidence, and there was wide variability in the type of EIP descriptions published. A strength however is that many of the domains identified in the narrative synthesis mirror items in Addington’s [Reference Addington, Norman, Bond, Sale, Melton, McKenzie and Wang8] fidelity scale, suggesting ecological validity. We adopted a bottom-up approach to data analysis, guided by thematic analysis, rather than adopting an implementation framework like the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to guide data analysis. Such an approach may have yielded differing results. Finally, stakeholders’ views on EIP efficacy did not emerge as a theme within survey of the literature, but a belief in a lack of EIP efficacy could lead to views that EIP investment is unjustified. Unfortunately, we cannot comment on this.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, this review highlights the generic and specific challenges to EIP implementation and sustainability with practical implications. The commonalities between domains suggest multiple potential avenues through which implementation can be driven. EIP has promoted recovery and increased access to care, but coverage is inconsistent. A better understanding of the EIP implementation gap and the ways in which it can be overcome, helps ensure these services can be accessed by a wider range of patients and families.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: N.O.C., C.D and K.O.C.; Data curation: N.O.C., D.M.G., and L.V.; Formal analysis: N.O.C., D.M.G., and L.V.; Methodology: N.O.C., C.D. D.M.G., L.V., and R.J.; Project administration: N.O.C. and D.M.G.; Funding acquisition: C.D., K.O.C. and R.J.; Supervision: C.D. K.O.C.; Validation: C.D. D.M.G. and L.V.; Writing – original draft: N.O.C.; Writing – review & editing: N.O.C., C.D., K.O.C., D.M.G., L.V., and R.J.

Data Availability Statement

Data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ireland’s new EIP Model of Care staff for their support throughout this research project.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the Health Service Executive of Ireland’s ‘National Clinical Programme for Early Intervention in Psychosis’.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2260.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.