Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound negative impact on the mental health of the general population [Reference Twenge and Joiner1–Reference Unützer, Kimmel and Snowden3]. The pandemic can be considered as a new type of traumatic stressor, being an unexpected event, affecting the whole population worldwide and causing a severe disruption of daily routine life [Reference Gorwood and Fiorillo4–Reference Horesh and Brown6]. Recent research suggests that traumatic stress reactions, including intrusive reexperiencing and heightened arousal, are frequent during the pandemic [Reference Bridgland, Moeck, Green, Swain, Nayda and Matson7] and may be due to its direct threats to important life resources of the general population, such as safety, health, income [Reference Hodgkin, Moscarelli, Rupp and Zuvekas8], work, housing, and social support [Reference Knapp and Wong9,Reference Ren, Zhou and Liu10]. Furthermore, the traumatic stress reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic may be worsened by the indirect exposure to the pandemic, for example, via mass-media coverage and the phenomenon of infodemic [Reference Calleja, AbdAllah, Abad, Ahmed, Albarracin and Altieri11,Reference Crocamo, Viviani, Famiglini, Bartoli, Pasi and Carrà12]; by the psychosocial consequences of the pandemic, in terms of unemployment, isolation [Reference Kato, Kanba and Teo13], nonsudden illness/death [Reference Elbogen, Lanier, Blakey, Wagner and Tsai14–Reference Wasserman, van der Gaag and Wise16]; and by the lack of clear and reliable therapeutic guidelines for the management of the COVID-19 infection [Reference Patrucco, Gavelli, Fagoonee, Solidoro, Undas and Pellicano17].

The negative consequences of the pandemic on the mental health may vary in different target populations, such as healthcare professionals, people infected by the COVID-19, people living with disabilities or affected by chronic physical and mental disorders [Reference Li, Yang, Qiu, Wang, Jian and Ji18] or special population, such as pregnant women [Reference Kinser, Jallo, Amstadter, Thacker, Jones and Moyer19–Reference Pugliese, Bruni, Carbone, Calabrò, Cerminara and Sampogna24], elderly [Reference Briggs, McDowell, De Looze, Kenny and Ward25,Reference Vannini, Gagliardi, Kuppe, Dossett, Donovan and Gatchel26] or young people [Reference Hoffmann, Pisinger, Rosing and Tolstrup27–Reference Squeglia30]. In particular, the psychiatric and psychological consequences of the pandemic on the general population mainly include high levels of distress [Reference Tyrer31,Reference Li, Ge, Yang, Feng, Qiao and Jiang32] and of post-traumatic reactions [Reference Norrholm, Zalta, Zoellner, Powers, Tull and Reist33–Reference Morina and Sterr35], social isolation with suicidal ideation [Reference Rooksby, Furuhashi and McLeod36–Reference Wasserman, Iosue, Wuestefeld and Carli39], depressive and anxiety symptoms and sleep disorders [Reference Krystal, Prather and Ashbrook40–Reference Karatzias, Shevlin, Hyland, Ben-Ezra, Cloitre and Owkzarek44]. A high prevalence of mental exhaustion, burn-out syndrome and insomnia has been found in healthcare workers [Reference Fino, Bonfrate, Fino, Bocus, Russo and Mazzetti45–Reference Bryant47]. In disabled people and in those with pre-existing mental health problems, an increased risk of treatment interruption of long-term treatments has been found, associated with relapses or symptoms worsening, as well as with a higher risk of being infected by the COVID-19 [Reference Wang, Xu and Volkow48–Reference Coulombe, Pacheco, Cox, Khalil, Doucerain and Auger53]. Specific risk factors identified for the development of these mental health disturbances include female gender, having previous psychiatric or physical disorders, loneliness, time spent on the Internet, and unemployment [Reference Fiorillo, Sampogna, Giallonardo, Del Vecchio, Luciano and Albert54,Reference Mertens, Gerritsen, Duijndam, Salemink and Engelhard55].

Although these different populations are exposed to the same traumatic event (i.e., the pandemic), its perception is highly variable, because it is mediated by individual psychological and social factors, such as coping strategies and resilience styles [Reference Sampogna, Del Vecchio, Giallonardo, Luciano, Albert and Carmassi56–Reference Wlodarczyk, Basabe, Páez, Amutio, García and Reyes60].

When facing a traumatic event, some people may also experience positive changes, the so-called posttraumatic growth (PTG) [Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun61,Reference Mitchell, Gallaway, Millikan and Bell62]. The PTG is a substantive, positive change in a person’s self-perceptions, relationships with others, and/or their personal philosophy of life, resulting after a traumatic experience [Reference Taku, Tedeschi, Shakespeare-Finch, Krosch, David and Kehl63,Reference Seery, Holman and Silver64]. PTG consists of five dimensions [Reference Prati and Pietrantoni65]: (a) changes in how people relate with others (i.e., an increased willing to express emotions or even accepting more likely help from others); (b) recognition of new possibilities (i.e., seen as an increased attitude to take new paths in life and redefine priorities); (c) a sense of greater personal strength (i.e., improved sense of self-efficacy, strength, and self-confidence); (d) changes toward spirituality (i.e., religious beliefs, spiritual matters, and existential/philosophical questions); and (e) greater appreciation of life (i.e., considering meaningful and worth in life’s little things).

Some studies [Reference Muldoon, Haslam, Haslam, Cruwys, Kearns and Jetten66–Reference Luciano, De Rosa, Del Vecchio, Sampogna and Sbordone70] highlighted how a collective experience of trauma can help people reflecting on their traumatic experiences, as it would be the case for the COVID-19 pandemic [Reference Venuleo, Gelo and Salvatore71]. Understanding the possible positive consequences of the pandemic on the individual level is crucial for the development of preventive and supportive psychosocial interventions for the general population [Reference Ghebreyesus72–Reference Kuzman, Curkovic and Wasserman76]. Furthermore, the sociodemographic and clinical factors facilitating the positive adaptation to trauma may be worth to identify.

During the initial phase of the pandemic, Italy has been among the most severely hit countries, with high rates of COVID-related morbidity and mortality, high occupancy rate in intensive care units and extreme burden on the national health systems. Therefore, the Italian government issued severe public health measures, with lockdown and quarantine in order to limit the spread of the disease. The COvid Mental hEalth Trial (COMET) study is a multicentric, collaborative, notfunded trial carried out during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, targeting the Italian general population during the first wave of the lockdown [Reference Fiorillo, Sampogna, Giallonardo, Del Vecchio, Luciano and Albert54,Reference Giallonardo, Sampogna, Del Vecchio, Luciano, Albert and Carmassi77].

Based on the COMET study, the present paper aims to: (a) evaluate the levels of PTG in a sample of the general population and (b) to identify predictors of each dimension of post-traumatic growth.

Materials and Methods

The present paper is based on data collected in the COMET [Reference Fiorillo, Sampogna, Giallonardo, Del Vecchio, Luciano and Albert54,Reference Giallonardo, Sampogna, Del Vecchio, Luciano, Albert and Carmassi77].

The COMET study has been coordinated by the University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” (Naples), and includes other Italian university sites (Università Politecnica delle Marche [Ancona], University of Ferrara, University of Milan Bicocca, University of Milan “Statale,” University of Perugia, University of Pisa, Sapienza University of Rome, “Catholic” University of Rome, and University of Trieste) with the Center for Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health of the National Institute of Health in Rome. The COMET trial has been designed as cross-sectional study, adopting a snowball sampling procedure [Reference Giallonardo, Sampogna, Del Vecchio, Luciano, Albert and Carmassi77].

The main outcome measure considered in the present study is represented by the levels of Post Traumatic Growth, which have been evaluated by using the short form of the Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) [Reference Cann, Calhoun, Tedeschi, Taku, Vishnevsky and Triplett78]. The PTGI consists of 10 items, rated on a 6-point Likert scale (i.e., 0 = “I did not experience this change as a result of my crisis”; 5 = “I experienced this change to a very great degree as a result of my crisis”). Items are grouped in following five dimensions: (a) relating to others; (b) new possibilities; (c) personal strengths; (d) spiritual change; and (e) appreciation of life. It is calculated a total score, so that higher scores indicate higher levels of post-traumatic growth. Responses on the items were averaged to form the scale score, and the attainment of substantial PTG was indicated by an average score of 4 [Reference Ng79].

The survey includes also the following validated self-reported questionnaires: DASS-21 [Reference Lovibond and Lovibond80]; General Health Questionnaire—12 items version (GHQ) [Reference Goldberg, Gater, Sartorius, Ustun, Piccinelli and Gureje81]; Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory—Revised version (OCI-R) [Reference Foa, Huppert, Leiberg, Langner, Kichic, Hajcak and Salkovskis82]; Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) [Reference Morin, Belleville, Bélanger and Ivers83]; Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scale (SIDAS) [Reference van Spijker, Batterham, Calear, Farrer, Christensen and Reynolds84]; Severity of Acute Stress Symptoms Adult Scale (SASS) [Reference Kilpatrick, Resnick and Friedman85]; the Impact of Event Scale—short version (IES) [Reference Thoresen, Tambs, Hussain, Heir, Johansen and Bisson86]; the UCLA loneliness scale—short version [Reference Hays and Di Matteo87]; the Brief-COPE [Reference Carver88]; the Connor–Resilience Scale [Reference Connor and Davidson89]; and the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPPS) [Reference Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet and Farley90]. Moreover, sociodemographic information (i.e., gender, age, civil status, level of education, number of cohabitations, geographical region, living in one of the most severely impacted area, working condition, and housing condition) have been collected through an ad hoc schedule.

This study is being conducted in accordance with globally accepted standards of good practice, in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki and with local regulations.

Written informed consents have been collected from participants in order to take part to the online survey. The present study protocol has been reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Board of the University of Campania “L. Vanvitelli” (Protocol number:0007593/i).

Statistical analysis

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the global sample have been analyzed using descriptive statistics and frequency tables, as appropriate. Differences in levels of PTG according to the different target groups (i.e., general population, healthcare workers, patients with pre-existing mental disorders, and people infected by COVID-19) were evaluated using chi-square with multiple comparisons and ANOVA with Bonferroni corrections.

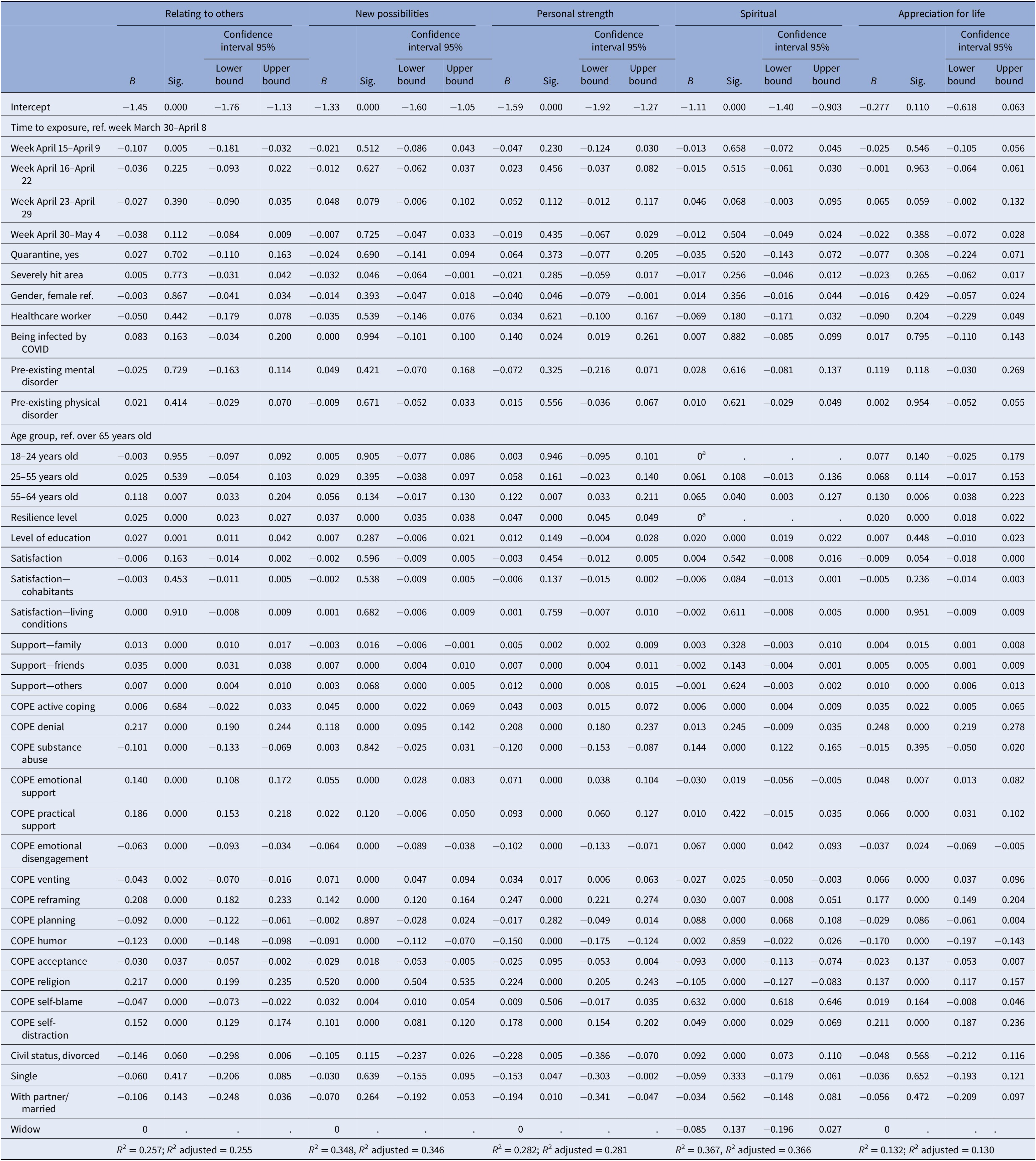

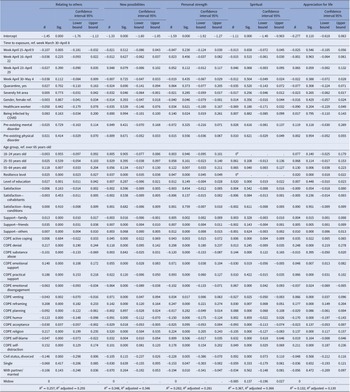

In order to assess the impact of the duration of lockdown on the different dimensions of post-traumatic growth (i.e., personal strength, relating to others, new possibilities, spiritual life, and appreciation for life) multivariate linear regression models were implemented. This statistical approach has been already adopted in previous published papers based on the COMET study [Reference Fiorillo, Sampogna, Giallonardo, Del Vecchio, Luciano and Albert54] and the categorical variable “Week” was entered in the regression models. Several sociodemographic characteristics, including gender, age, working status, having a physical comorbid condition, having a pre-existing mental disorder, civil status, level of education, satisfaction with one’s own life, and with housing conditions, adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies, having been infected by COVID-19 were entered in the models and adjusted for them.

Multiple imputation approach has been used for managing missing data. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 and statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 26.0, and STATA, version 15.

Results

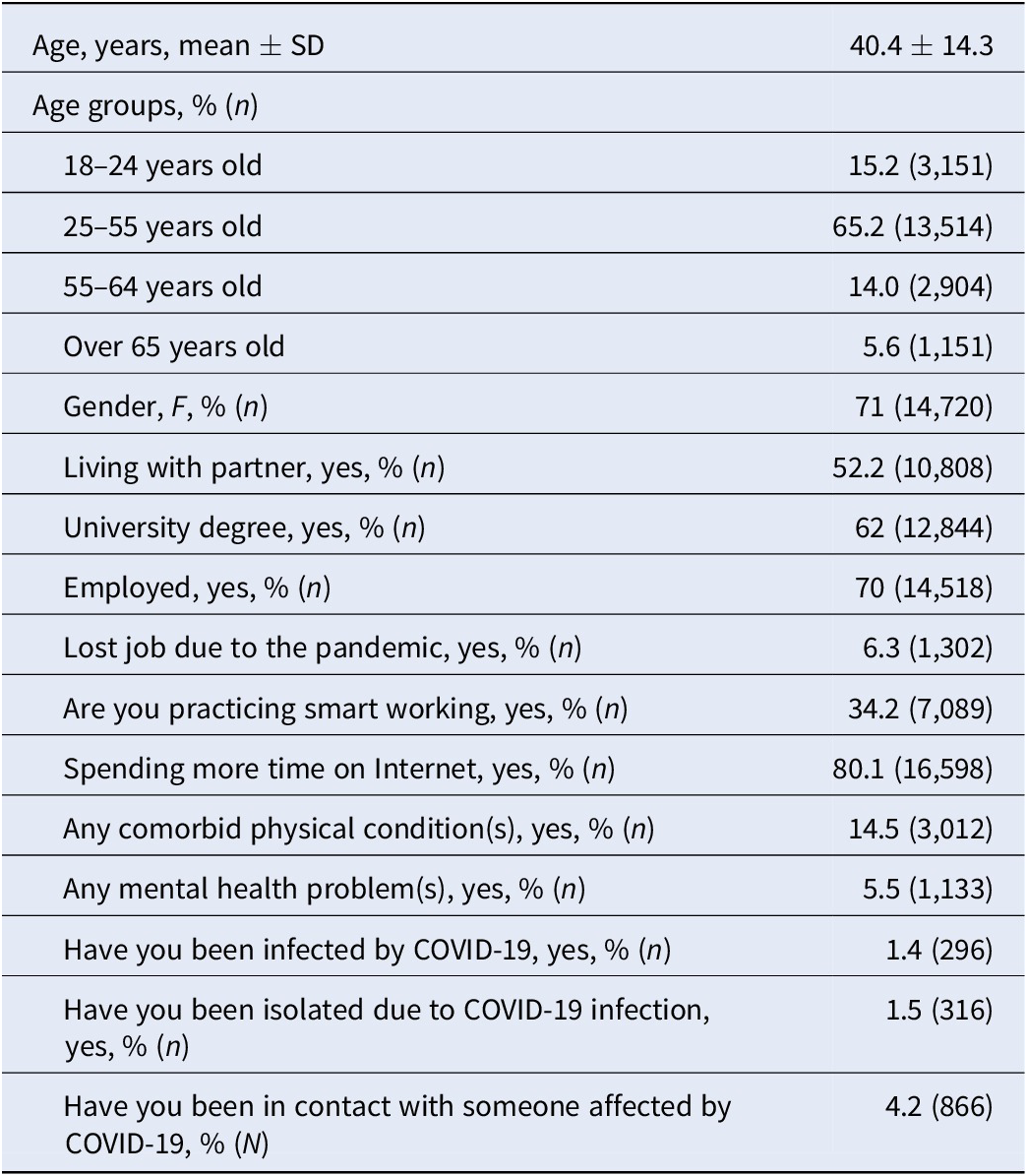

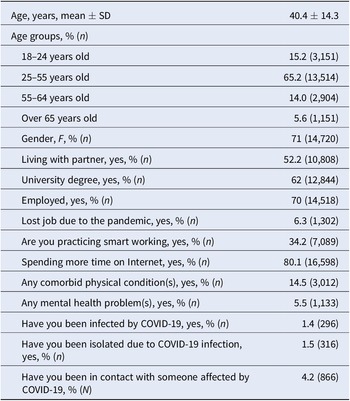

The final sample consists of 20,720 participants, mainly female (71%, N = 14,720) and with a mean age of 40.4 ± 14.3 years (Table 1), half of the respondents were in a stable relationship and were living with a partner.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the global sample (n = 20,720).

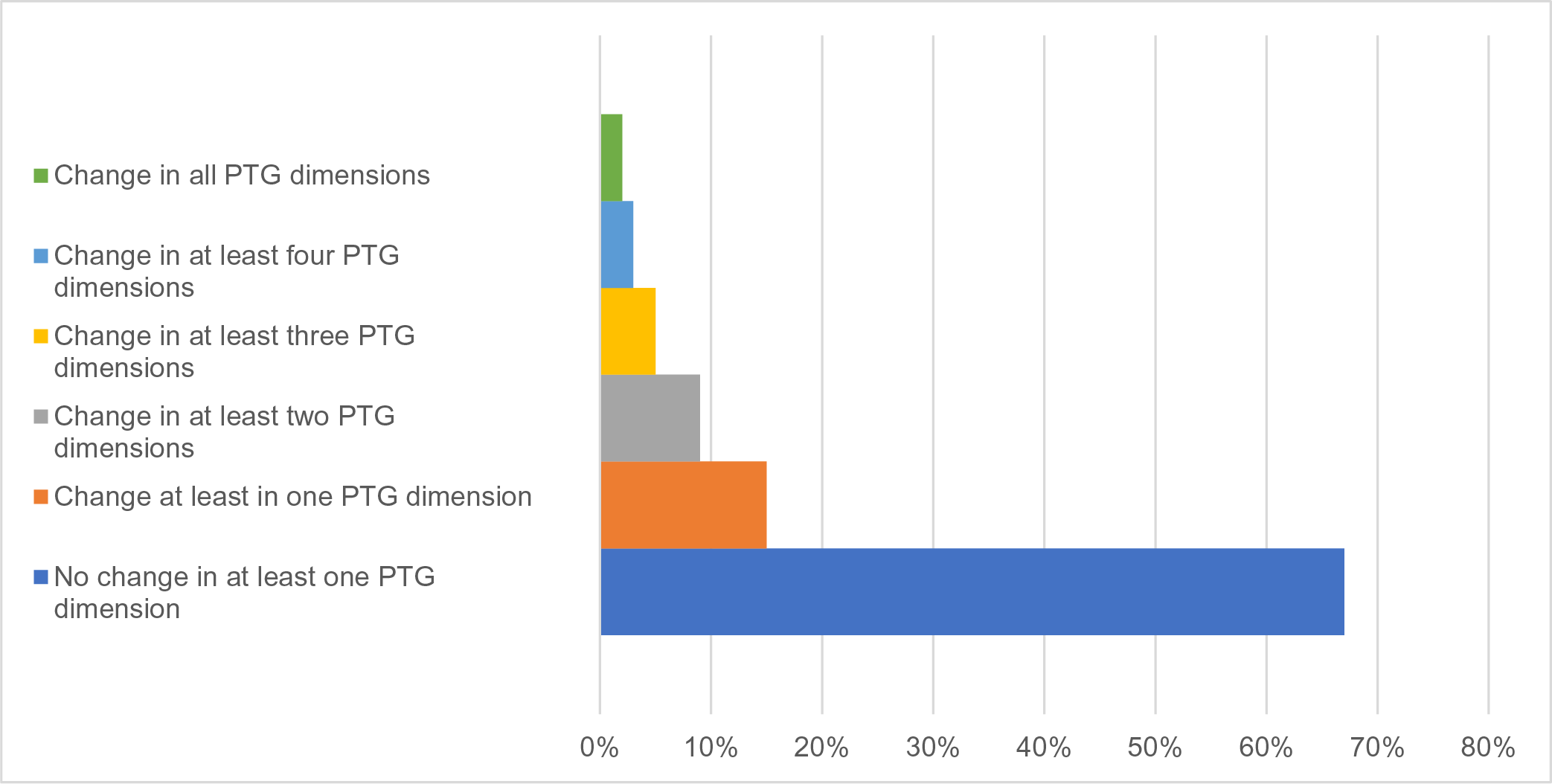

The majority of the sample (67%, N = 13,889) did not report any significant improvement in any domain of PTG (Figure 1). Only 4% of participants (N = 824) reported a substantial PTG (i.e., >4.0) by the overall scale score. Considering the specific dimensions of PTG, 18% (N = 3,739) of respondents achieved a significant post-traumatic growth in the dimensions of appreciation for life and personal strength, while only 4.8% (N = 1,003) of participants reported a change in spiritual life.

Figure 1. Percentage of participants with growth in at least one domain of PTG.

Participants reported the highest levels of growth in the dimension of “appreciation of life” (2.3 ± 1.4), while the lowest level was found in the “spiritual change” (1.2 ± 1.2).

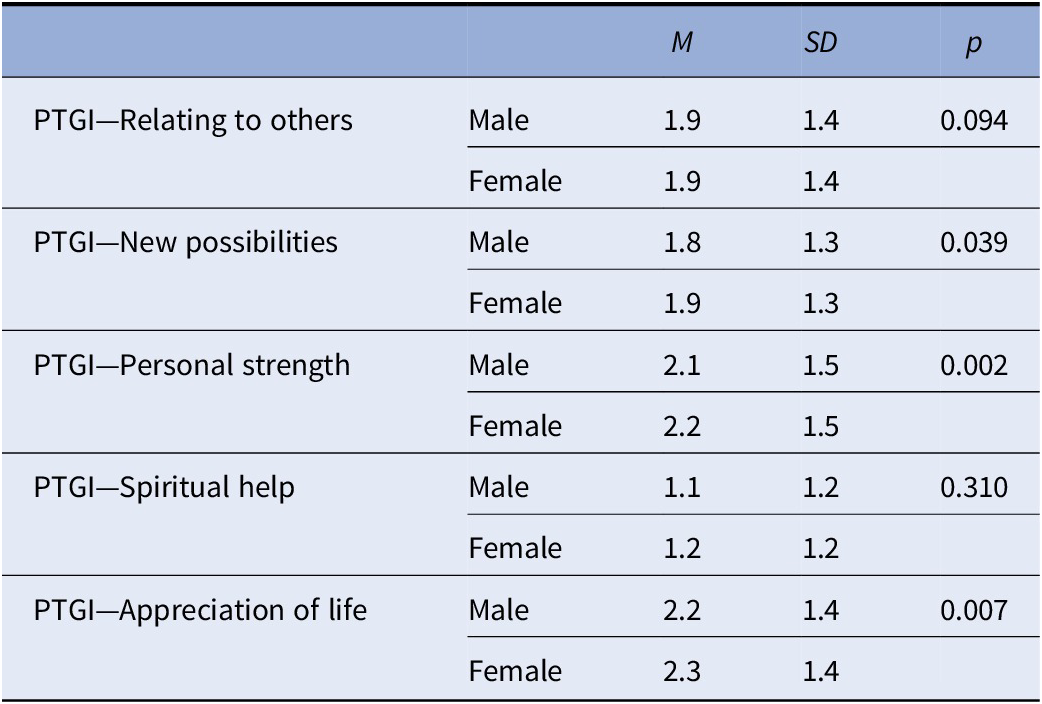

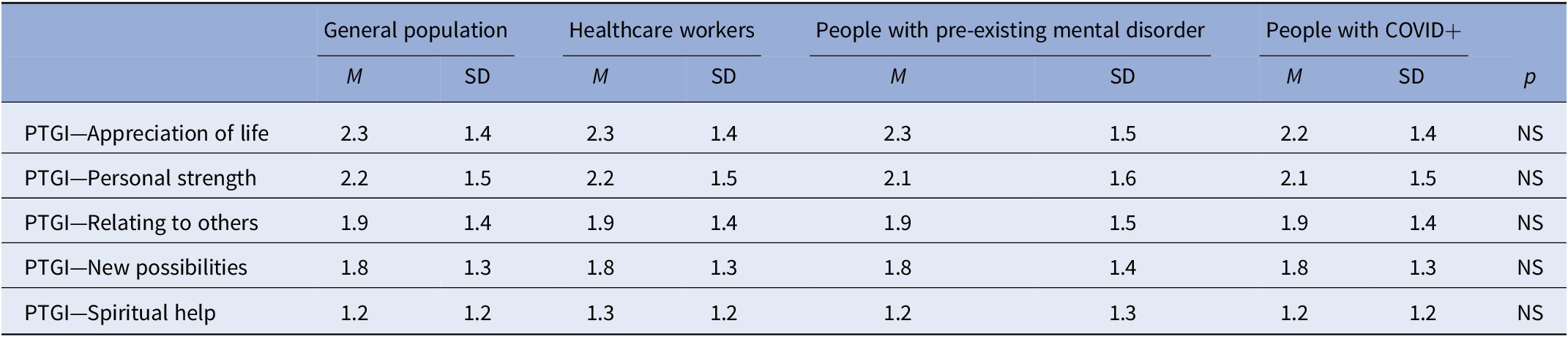

Female participants reported a slightly higher level of PTG in the dimensions of personal strength (p < 0.002) and appreciation for life (p < 0.007) compared to male participants, while no significant association was found with age (Table 2). No significant differences in the levels of PTG were found among healthcare professionals, people infected by COVID-19 and patients with pre-existing mental disorders, compared to the general population (Table 3).

Table 2. Gender differences in levels of PTG.

Abbreviations: M, mean; NS, not significant; PTGI, post-traumatic growth inventory; SD, standard deviation; p = p value.

Table 3. Differences in the levels of PTG.

Abbreviations: M, mean; NS, not significant; p, p value; PTGI, post-traumatic growth inventory; SD, standard deviation.

At the multivariate regression models, weighted for the propensity score, only the initial week of lockdown (between April 9 and April 15) had a negative impact on the dimension of “relating to others” of the PTG (B = −0.107, 95% CI = −0.181 to −0.032, p < 0.005), while over time no other effects were found. However, the duration of exposure to lockdown measures did not influence the other dimensions of PTG (Table 4).

Table 4. Predictors of levels of post-traumatic growth.

Abbreviations: B = beta coefficient; Model statistics: R 2 = R 2 adjusted. Sig = significance.

Factors significantly associated with the increase in the levels of PTG include the levels of resilience, with a B coefficient ranging from .025 (95% CI = 0.023 to 0.027) for “relating to others” (p < 0.000) to B = 0.047 (95%CI = 0.045 to 0.049) for “personal strength” (p < 0.000), the perceived support from family members and friends and the level of education. Furthermore, adaptive coping strategies, such as emotional support (B = 0.140, 95% CI = 0.108 to 0.172, dimension “relating to others”; B = 0.055, 95% CI = 0.028 to 0.083, dimension “new possibilities”; B = 0.071, 95% CI = 0.038 to 0.104; B = 0.048, 95% CI = 0.013 to 0.082, dimension “appreciation for life”), reframing (0.208, 95% CI = 0.182 to 0.233) and practical support (B = 0.186, 95% CI = 0.153 to 0.218) were significant predictors of several dimensions of PTG, including relating to others, new possibilities and appreciation for life. On the other hand, maladaptive coping strategies, including self-blame (B = −0.047, 95% CI = −0.073 to −0.022) and venting (B = −0.043, 95% CI = −0.070 to −0.016) were associated with a reduction of many dimensions of post-traumatic growth.

Living in one of the most severely hit areas of the pandemic was a negative predictor only for the “New possibilities” (B = −0.032, 95% CI = −0.064 to −0.001), but not for the other dimensions of PTG. Having a pre-existing mental or physical disorder, having being infected by COVID-19, being a healthcare worker did not have any impact on the several dimensions of post-traumatic growth.

Finally, in the different age groups, the probability of having higher levels of post-traumatic growth was found in people aged 55–64 years old, both for the dimension of relating to others (B = 0.118, 95% CI = 0.033 to 0.204) as well as for the dimension of personal strength (B = 0.122, 95% CI = 0.033 to 0.211).

Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate the levels of post-traumatic growth during the first wave of COVID-19 related lockdown in the general population. During the initial phase of the national emergency for the pandemic, Italy was one of the most severely hit areas in Europe, and strict containment measures were issued by the Italian government in order to limit the spread of the virus and its morbidity and mortality rate, since no vaccinations were available [Reference Eichenberg, Grossfurthner, Kietaibl, Riboli, Borlimi and Holocher-Benetka91]. This survey was promoted and disseminated in the Italian general population during the weeks of the first lockdown, a period of uncertainty, fears for the future and exceptional changes in the daily routine. All these sociocultural factors have contributed to feature the pandemic as a new type of traumatic stressor, which could have an impact on the mental health of the general population. Although several papers have reported increasing levels of anxiety, depressive and stress symptoms in the Italian general population [Reference Fiorillo, Sampogna, Giallonardo, Del Vecchio, Luciano and Albert54], as well as the presence of sleep disorders and of suicidal ideation, a few data are available on the possible positive consequences of the pandemic on the general population. Some studies have found that growth and distress are at opposite ends of the same continuum, from which a negative association was found [Reference Winefield, Gill, Taylor and Pilkington92]. Alternatively, growth has been thought to positively coexist with distress, with some authors stating that “the higher the distress, the better the growth” [Reference Dekel, Mandl and Solomon93]. In the present study, we found that respondents did not report high levels of post-traumatic growth, with only 15% reporting a significant growth at least in one dimension. This data is in line with those found in Hong-Kong, where post-traumatic growth was found in less than 20% of the general population [Reference Lau, Chan and Ng94,Reference Kwok, Li, Chan, Yi, Tang and Wei95]. Other studies carried out in China reported levels of post-traumatic growth of up to 50% in at least one domain of PTG. These differences could be due to the divergence in social contexts among countries, in terms of social cohesion, acceptance and satisfaction with the governmental measures for containing the pandemic and the perception of collective identity [Reference Zmerli and Newton96,Reference Voci97]. Therefore, it is of extreme interest to understand the possible impact of these necessary and unavoidable containment measures on the mental health of the general population, in order to develop appropriate supportive and preventive interventions to mitigate the long-term negative effects of the pandemic on mental health.

Regarding the several PTG dimensions, we found that scores of “appreciation of life” were the greatest, while “spiritual change” was the lowest. These results are in line with those reported by Prati and Pietrantoni [Reference Prati and Pietrantoni98], confirming that our findings can be considered representative of the Italian general population.

Another interesting finding is that higher levels of post-traumatic growth during the initial phase of the pandemic were found in female participants. Previous studies carried out during other natural emergencies have found a gender difference in the levels of post-traumatic growth [Reference Zwahlen, Hagenbuch, Carley, Jenewein and Buchi99]. Although little research has examined the underlying processes for such gender differences in PTG, the role of some cognitive styles, such as rumination, has been proposed [Reference Zwahlen, Hagenbuch, Carley, Jenewein and Buchi99,Reference Petzold, Bendau, Plag, Pyrkosch, Mascarell Maricic and Betzler100]. In particular, the tendency to ruminate on constructive issues, such as an increased awareness of personal strengths or an appreciation of the importance of social connections, has been suggested as the mechanism leading to the greater reports of PTG [Reference Kim and Bae101]. In different groups of traumatized people, such as bereaved parents or women at a high risk for breast cancer, the use of reflective rumination was associated with high levels of post traumatic growth [Reference Vishnevsky, Cann, Calhoun, Tedeschi and Demakis102–Reference Antoni, Lehman, Klibourn, Boyers, Culver and Alferi104].

Another potential mediator while processing traumatic events is the type of coping strategies adopted. In fact, we found that using adaptive coping strategies, such as planning, practical support and reframing, predicted higher levels of post-traumatic growth. This finding is in line with previous COVID-related data [Reference Fiorillo, Sampogna, Giallonardo, Del Vecchio, Luciano and Albert54,Reference Kar, Kar and Kar105] but also with other studies carried out on factors moderating the impact of traumatic events [Reference Kim and Bae101,Reference Sattler, Bloyd and Kirsch106,Reference Teasdale, Yardley, Schlotz and Michie107]. PTG may be conceptualized as a cognitive adaptive process among those who experience traumatic stress in response to a disaster, in terms of a positive reinterpretation and positive reframing of the negative experience. However, the use of adaptive coping strategies can sustain and booster this process and it is therefore essential to promote the dissemination of psychosocial interventions aiming to teach and improve adaptive coping strategies in the general population.

Contrary to what we expected, we did not find a significant effect of the weeks of lockdown on the levels of post-traumatic growth, except for the dimension of “searching new possibilities.” This finding is particularly striking if we consider that the levels of stress and of psychiatric symptoms tended to increase over time [Reference Fiorillo, Sampogna, Giallonardo, Del Vecchio, Luciano and Albert54]; it may be that PTG is not related to the duration of the traumatic event, but it is related to the nature of the trauma and to the personality traits and characteristics of the individual [Reference Ellena, Aresi, Marta and Pozzi108]. Of course, this interpretation deserves more studies. Furthermore, patients with pre-existing severe mental disorders did not show significantly lower levels of PTG, compared to the general population. This was an unexpected finding, which should be due to the ability, skills and personal resources of patients to adapt to the “new” life routine posed by the pandemic. Moreover, a possible time-lead effect should explain this finding, being the levels of PTG quite high at the initial phase of the pandemic, and it should be reduced over the following months.

The present study has some limitations, which are hereby acknowledged. First, the online snowball sampling methodology may have led to a selection bias, with only those interested in the psychological consequences of the pandemic willing to participate [Reference Baltar and Brunet109]. Second, the cross-sectional design of the survey prevents us to delineate any causal relationship between the selected variables. Finally, several variables, such as social cohesion, national identity and interpersonal trust, personality traits and cognitive styles should have had an impact on the levels of post-traumatic growth [Reference Ellena, Aresi, Marta and Pozzi108,Reference Wong and Yeung110].

Conclusions

The assessment of the levels of post-traumatic growth in the general population during the initial phase of the national health emergency is of great importance for the development of ad hoc supportive and preventive psychosocial interventions [Reference Kaufman, Petkova, Bhui and Schulze111–Reference Reynolds114]. It has been repeatedly stated that the pandemic will have longstanding, and far-reaching, consequences on global mental health and wellbeing to the whole population, regardless of age and gender [Reference Sinha, Collins and Herrman115–Reference Jorm, Kitchener and Reavley118]. From a public health perspective, the identification of protective factors is crucial for developing ad hoc tailored interventions and for preventing the development of full-blown mental disorders in large scale [Reference Kahn, Cohen, Tubiana, Legrand, Wasserman and Carli119–Reference Barry, Clarke and Petersen122]. From a clinical practice perspective, the promotion of supportive interventions aiming to improve the levels of resilience, the adaptive coping strategies and the levels of post-traumatic growth should be prioritized in order to mitigate the detrimental effects of the pandemic.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is not available for sharing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: G.M., G.S.; Formal analysis: G.S.; Investigation: A.T.; Methodology: A.T.; Supervision: G.C., M.P.; Writing—original draft: G.M., A.T.; Writing—review and editing: U.A., V.B., C.C., G.C., F.C., B.D.O., M.F., F.P., M.P., M.G.N., U.V., G.Sa., A.T.

Financial Support

This research received no external funding.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.