1. Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) are known to impact life in several ways. Even though there are heterogeneous approaches what to include when ACEs are assessed, they are usually distinguished between ACEs related to household dysfunction and child maltreatment [Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart and Mikton1]. Household dysfunction are ACEs that affect the child in an indirect way via their environment, and encompass mental illness and substance abuse of any household member, intimate partner violence (IPV), parental separation and incarceration of a household member. Maltreatment, on the other hand, is directed at the child and can be distinguished into 5 subtypes: emotional, physical and sexual abuse and emotional and physical neglect (see Fig. 1).

Fig 1. Overview of adverse childhood experiences. Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) can be divided into household dysfunctions, which affect the child in an indirect way, and child maltreatment.

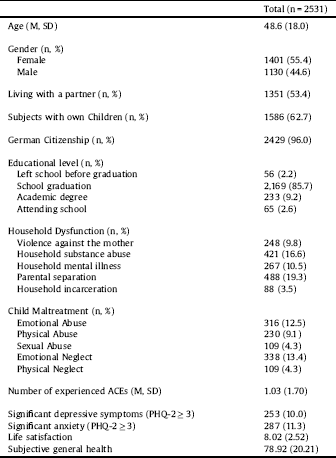

Table 1 Sample Characteristics.

Sample Characteristics. Data are presented as mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) for age, life satisfaction and subjective general health and number of subjects (%) for other characteristics.

Household dysfunction and child maltreatment often co-occur, are inter-related and have cumulative negative effects [Reference Dong, Anda, Felitti, Dube, Williamson and Thompson2, Reference Brown, Rienks, McCrae and Watamura3]. The number of experienced ACEs is known to have comprehensive effects for mental and somatic health, quality of life [Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart and Mikton1] and to reduce life expectancy for up to 20 years [Reference Brown, Anda, Tiemeier, Felitti, Edwards and Croft4]. Focusing on consequences of specific ACEs, it was shown that ACEs related to both, household dysfunction and child maltreatment, have devastating consequences. Child maltreatment may lead to psychosocial and economic impairment, massive mental and somatic health problems and a significant reduction in quality of life [Reference Norman, Byambaa, De, Butchart, Scott and Vos5]. Next to the individual level, child maltreatment results in enormous economic costs with annual expenses between 11 and 30 billion Euro in Germany alone [Reference Habetha, Bleich, Weidenhammer and Fegert6]. Experiences of ACEs related to household dysfunction result in developmental and cognitive impairment [Reference Neamah, Sudfeld, McCoy, Fink, Fawzi and Masanja7, Reference World Health Organization8], higher risks for mental disorders [Reference Slopen and McLaughlin9–Reference Rasic, Hajek, Alda and Uher12] and social problems [Reference Bowen13]. Therefore, household dysfunction and child maltreatment are considered major public health problems.

Several factors are discussed as reasons for the devastating effects of household dysfunctions. Parenting skills and parent-child interactions are known to be impaired in mothers who have experienced IPV [Reference Levendosky, Bogat and Huth-Bocks14], as well as in mentally ill [Reference Widom, Czaja, Kozakowski and Chauhan15] and substance abusing parents [Reference Kelley, Lawrence, Milletich, Hollis and Henson16]. Parental separation can go along with reduced contact to one parent and lower secure parent–child attachment [Reference Woodward, Fergusson and Belsky17]. Incarceration usually goes along with separation from a primary caregiver [Reference Dallaire18]. Moreover, biological and psychosocial factors are hypothesized [Reference Goodman19–Reference Averdijk, Malti, Eisner and Ribeaud21]. It was shown for each particular category of household dysfunction to be an important risk factor for child maltreatment by itself [Reference Dong, Anda, Felitti, Dube, Williamson and Thompson2, Reference Brockington, Chandra, Dubowitz, Jones, Moussa and Nakku11, Reference Brown, Cohen, Johnson and Salzinger22–Reference Ahmadabadi, Najman, Williams, Clavarino, d’Abbs and Abajobir27]. This may be one of the main factors for the long-term consequences of household dysfunctions. Unfortunately, to the best of our knowledge, there are no analyses assessing the role of child maltreatment as potential mediator for the observed long-term consequences of household dysfunctions.

This is surprising, as more knowledge about the interplay between household dysfunction and child maltreatment is indispensable for the development of targeted intervention programs in order to reduce the massive impact of ACEs.

Therefore, we investigated the occurrence of child maltreatment in dependence of household mental illness, substance abuse, violence against the mother, incarceration of a household member and parental separation in a population based survey. A population based sample from the age of 14 was chosen to make sure that both short and long term consequences of household dysfunction and maltreatment could be detected. To provide a better understanding for the mechanisms leading to the fatal consequences of ACEs, we furthermore assessed whether the long-term consequences of household dysfunction were mediated by child maltreatment and thereby might be targetable by tailored child protection programs.

2. Methods

2.1 Sample

Using a random route procedure, a representative sample of the German population was obtained by a demographic consulting company (USUMA, Berlin, Germany). Data collection took place between November 2017 and February 2018. To ensure representativeness a systematic area sampling, based on the municipal classification of the Federal Republic of Germany and covering the entire inhabited area of Germany was used. On the base of this data, around 53,000 areas in Germany were delimited electronically, containing an average of around 700 private households. These areas were first layered regionally according to districts to divide them into a total of around 1500 regional layers. Then 128 so-called networks were drawn in proportion to the distribution of private households. In the second and subsequent third selection stages, private households were selected systematically at random and the respective target persons within these households. Households of every third residence in a randomly chosen street were invited to participate in the study. To select participants in multi-person households a Kish-Selection-Grid was applied. For inclusion, participants had to be at least 14 years of age and have sufficient German language skills. Of 5160 initially contacted households, 2531 persons completed the survey. The main reasons for non-participation were refusal by the selected household to identify the person of target (16.5%, referring to the initial 5160 households), refusal of the target person to participate (15.8%) and failure to contact anyone in the residence after four attempts (14.4%). The resulting sample was representative for the German population above the age of 14 in regard to age and gender.

Individuals who agreed to participate were given information about the study and informed consent was obtained. In the case of minors, participants gave informed assent with informed consent being provided by their caregivers. Participants were told that the study was about psychological health and well-being. Responses were anonymous. In a first step, socio-demographic information was obtained in an interview-format by the research staff face-to-face according to the demographic standards of the Federal Statistical Office. Then, the researcher handed out a copy of the questionnaire and a sealable envelope. This questionnaire was answered independently due to the sometimes very personal information provided. The researcher remained nearby in case the participants needed further information or left the household based on the participants wishes. Anyhow, the researcher did not interfere with filling out the questionnaire. The completed questionnaires were linked to the respondent’s demographic data, but did not contain name, address, or any other identifying information.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and fulfilled the ethical guidelines of the International Code of Marketing and Social Research Practice of the International Chamber of Commerce and of the European Society of Opinion and Marketing Research. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Department of the University of Leipzig.

2.2 Measures

The prevalence of ACEs was assessed using the German Version of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire, a standard screen for the retrospective assessment of ACEs. The questionnaire encompasses 10 items, one for each ACE. The single items are: emotional, physical and sexual abuse, emotional and physical neglect, separation of parents, mental illness, substance abuse and incarceration of a household member and violence against the mother in a dichotomous manner (yes/no). Psychometric properties of the German version of the ACE were demonstrated by Wingenfeld and colleagues with a satisfying internal consistency (Cronbachs α = 076) [Reference Wingenfeld, Schäfer, Terfehr, Grabski, Driessen and Grabe28]. In our sample, Cronbachs α was 0.77. Life satisfaction was assessed via a self-rating by the question” How satisfied are you, all in all, with your life?”, scale 1 (not satisfied at all) to 11 (totally satisfied) after Beierlein and colleagues [Reference Beierlein, Kovaleva, László, Kemper and Rammstedt29]. General health status was assessed with the EuroQol visual analogue scale (EQ VAS) with the question” How good or bad you think your personal health is today?”, scale 0 (worst) to 100 (best) [Reference Herdman, Gudex, Lloyd, Janssen, Kind and Parkin30]. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), a screening tool with a sensitivity of 82% and a specificity of 92% for major depressive disorder for a cut-point of ≥3 [Reference Lowe, Kroenke and Grafe31]. Anxiety was assessed with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 2-item (GAD-2), a screening questionnaire with a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 83% for generalized anxiety disorder for a cut-point of ≥3 [Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, Monahan and Löwe32]. In our sample, Cronbachs α was 0.78 for the PHQ-2 and 0.80 for the GAD-2.

2.3 Participants

Of the N = 2531 participants, between 2,501–2,526 participants (depending on the analysis) were included in the sample. The others were excluded due to missings on the respective data. Participants were on average 48.6 years old (SD = 18.0) and 56.4% were female. 96% reported to have German citizenship. The sample was representative for the German population in regard to age and gender compared to. The characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

2.4 Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21. Descriptive analyses were performed for prevalence rates. Comparisons were performed by Chi2- or t-tests depending on measurement level. Risks were calculated by Odds Ratios using Chi2-tests.

Mediation analyses were performed with the macro PROCESS by Hayes [Reference Hayes33] for SPSS. Ordinary last squares path analyses were conducted using 5000 bootstrapping samples. The presence or absence of household mental illness, substance abuse, violence against the mother, incarceration of a household member and parental separation were used in separate simple linear regression analysis as independent variable. Depending on the analyses, depression via PHQ score, anxiety as GAD score, life satisfaction and self-reported health were used as dependent variables. The number of experienced different maltreatment subtypes (0–5; emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect) served as mediation variable. The direct association is presented as c, the indirect association as c’.

3. Results

In total, participants reported they had experienced a mean number of 1.03 (±1.70) of ACEs during childhood. In detail, a total of n = 248 (9.8%) reported they had witnessed violence against the mother, 421 (16.6%) had lived with a household member with substance abuse and 267 (10.5%) had lived with a household member with mental illness in childhood. 488 (19.3%) reported that they had experienced parental separation and 88 (3.5%) had an incarcerated household member. Regarding child maltreatment, 316 (12.5%) of the participants reported emotional abuse, 230 (9.1%) physical abuse, 109 (4.3%) sexual abuse, 338 (13.4%) emotional neglect and 109 (4.3%) physical neglect (see Table 1).

3.1 Household dysfunction is associated with increased risk for all subtypes of child maltreatment

Prevalence of all subtypes of child maltreatment increased, when any one of the assessed household dysfunctions - mental illness, substance abuse, violence against the mother, incarceration of a household member or parental separation - was reported.

In detail, household mental illness was associated with an increased risk for all child maltreatment subtypes (ORs 4.95–5.55), household substance abuse with increased risks between five- and sevenfold (ORs 5.32–6.98) and violence against the mother with increased risks between four- and tenfold (ORs 4.43–10.26). The strongest increase for the risk of child maltreatment was seen if incarceration of a household member was reported (ORs 6.11–14.93, depending of the maltreatment subtype), the lowest increase if parental separation had occurred (ORs 3.37–4.87; for details see Table 2).

Table 2 Prevalence and risk of child maltreatment in dependence of household mental illness, substance abuse and violence against the mother.

Prevalence of maltreatment subtypes in dependence of experienced household dysfunction. Violence against the mother, substance abuse or mental illness of any household member. Presented as Number (N) and Percentages (%) or odds ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Interval (CI).

*** p < 0.001.

The mean number of experienced maltreatment subtypes increased in case of any reported ACE linked to household dysfunction (for details see Table 2).

3.2 Child maltreatment mediates the long-term consequences of household dysfunction

The association of violence against the mother with depression, anxiety and general health status was mediated completely by child maltreatment. The association of IPV and these outcomes approached zero and lost statistical significance if child maltreatment was included in the calculation. The association with life satisfaction was partially mediated via child maltreatment. The association was reduced by half after inclusion of child maltreatment and still statistically significant (for details see Fig. 2).

Child maltreatment partially mediated also the association of household substance abuse with all assessed long-term outcomes (for details see Fig. 3).

The association of mental illness of a household member with depression, anxiety, life satisfaction and general health was mediated partially by child maltreatment (for details see Fig. 4).

The association of an incarcerated household member with depression, anxiety and general health status was mediated completely by child maltreatment, meaning that these associations can be explained with the higher risks for maltreatment in the case of incarceration of a household member. The association of an incarcerated household member with life satisfaction was partially mediated via child maltreatment (for details see Fig. 5).

The association of parental separation with depression and anxiety was mediated partially by child maltreatment. The association was reduced by more than half after inclusion of child maltreatment. The association of parental separation with life satisfaction was mediated completely by child maltreatment. There was no significant association seen for parental separation and subjective general health status (for details see Fig. 6).

4. Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the association of ACEs linked to household dysfunction and child maltreatment in a representative sample in Europe. The present analysis shows strongly increased risks for physical, emotional and sexual abuse as well as physical and emotional neglect during childhood if violence against the mother, substance abuse or mental illness of any household member during childhood was reported. Strikingly, our results demonstrate that the assessed long-term consequences of household dysfunction regarding the health of affected children are mediated partly or completely by child maltreatment. The enhanced risk for child maltreatment of household dysfunction is known. Felitti et al. showed a high correlation between different adverse childhood events in the original ACE Study [Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz and Edwards24]. In a later analyses based on the same data, Felitti et al. showed increased ratios for child maltreatment in case of household substance abuse (odds ranging between 2.1–3.0 in dependence of the subtype of maltreatment), mental illness (odds 2.1–4.2), domestic violence (odds 2.5–5.9), incarcerated household member (odds 2.3–2.7) and parental separation (odds 2.0–2.6) [Reference Dong, Anda, Felitti, Dube, Williamson and Thompson34]. A study from Ohashi and colleagues showed in a Japanese sample that the risk for child maltreatment increases with the number of ACEs related to household dysfunction [Reference Ohashi, Wada, Yamaoka, Nakajima-Yamaguchi, Ogai and Morita35]. In an Australian study, where a sample of 7223 mothers and their offspring was assessed, odds for maltreatment ranged between 2.0 and 3.5 in case of IPV in dependence of maltreatment subtype and gender of the child [Reference Ahmadabadi, Najman, Williams, Clavarino, d’Abbs and Abajobir27]. As all these data, including the here presented results, are based on retrospective self-report that may be affected by recall bias. This could result in an underestimation of the presented results and it should be kept in mind that odds for maltreatment may be even higher.

Fig 2. Association between intimate partner violence (IPV) against the (step-) mother, child maltreatment and depression (A), anxiety (B), life satisfaction (C) and general health status (D), assessed via mediation analysis. Direct association is presented as c, indirect association as c’. b = beta coefficient; *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

Fig 3. Association between household substance misuse, child maltreatment and depression (A), anxiety (B), life satisfaction (C) and general health status (D), assessed via mediation analysis. Direct association is presented as c, indirect association as c’. b = beta coefficient; *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

Fig 4. Association between household mental illness, child maltreatment and depression (A), anxiety (B), life satisfaction (C) and general health status (D), assessed via mediation analysis. Direct association is presented as c, indirect association as c’. b = beta coefficient; *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

Fig 5. Association between incarceration of a household member, child maltreatment and depression (A), anxiety (B), life satisfaction (C) and general health status (D), assessed via mediation analysis. Direct association is presented as c, indirect association as c’. b = beta coefficient; *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

Fig 6. Association between parental separation, child maltreatment and depression (A), anxiety (B), life satisfaction (C) and general health status (D), assessed via mediation analysis. Direct association is presented as c, indirect association as c’. b = beta coefficient; *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

Reasons for the increased risk of maltreatment in dysfunctional households might be multifactorial. Socioeconomic status, isolation, stigma are risk factors for but also a result of ACEs [Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz and Edwards24, Reference Thornberry, Matsuda, Greenman, Augustyn, Henry and Smith36–Reference Ross, Waterhouse-Bradley, Contractor and Armour42]. It is this interwoven relationship of risk factors that makes it so complex to identify the crucial starting points for preventive measures. Other, more specific factors linked to household dysfunction encompass e.g. the parental ability to control impulses and to cope with frustration and anger - skills and capacity needed to manage daily requirements and stress as well as to maintain a warm and secure relationship to a child [Reference Bosanac, Buist and Burrows43–Reference Parolin and Simonelli46]. Parental separation and incarceration of a household member can be linked to impairment of the relationship or even loss of contact to primary caregiver [Reference Woodward, Fergusson and Belsky17, Reference Dallaire18].

In the present analyses, we found the highest risks for maltreatment for incarceration of a household member and violence against the mother. Furthermore, in contrast to household substance abuse and mental disorders, the associations of incarceration and IPV with anxiety, depression and general health status were mediated completely by child maltreatment. This suggests that long-term consequences for the health of affected children and adolescents may be prevented if interventions focus on child protection and maltreatment could be hindered. This suggests that prevention of long term consequences for affected children always need to focus these children directly. There might be no such thing as “collateral benefit” to the children when household dysfunction is improved without assessment of child maltreatment. A close link between IPV and all forms of child maltreatment is known from the literature [Reference Hamby, Finkelhor, Turner and Ormrod47]. A parent who uses physical violence against the partner is at higher risk to be violent against other parts of the family. Perpetrators of IPV are often low in dispositional self-control, have lower self-regulatory resources and higher aggressive potential [Reference Finkel, DeWall, Slotter, Oaten and Foshee48]. Therefore, the increased risks we could show for not only physical abuse, but also other maltreatment subtypes, are not surprising. Moreover, IPV is usually going along with witnessing of domestic violence and exposure to verbal aggression for the child [Reference MacMillan, Wathen and Varcoe26]. In an observational study including a sample of 554 subjects, Teicher and colleagues emphasized the role of IPV by showing that the effect of domestic violence and verbal abuse combined was higher than the effect of familiar sexual abuse on long-term outcomes including depression and anxiety [Reference Teicher, Samson, Polcari and McGreenery49]. Incarceration is often going along with a sudden loss of a household member and increased stress, a loss of financial and social support, and a higher workload for the remaining family [Reference Nesmith and Ruhland50]. Furthermore, incarceration might be due to aggressive behavior that may have also been directed against family members including children.

The associations of the assessed long-term consequences of household substance misuse, mental illness and parental separation were mediated partly by child maltreatment, suggesting that significant parts of the long-term consequences of affected children could be prevented by effective protection from maltreatment.

Taken together, our results demonstrate that children living in dysfunctional households are at higher risk for maltreatment and therefore should be considered by tailored preventive strategies. There are known obstacles to target these high-risk families. Reasons include fear of stigmatization and loss of custody at the family side [Reference Heard-Garris, Winkelman, Choi, Miller, Kan and Shlafer51, Reference Radcliffe52] and a lack of systematical screening for underage children in families where household dysfunctions become evident, e.g. in adult psychiatric care, on the institutional side. Nevertheless, there are some promising results that interventions targeting these high-risk families can be successful. One randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed that an intervention including social support, psycho-education and coping skills training can help to reduce the consequences of ACEs linked to household dysfunction [Reference van Santvoort, Hosman, van Doesum and Janssens53]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis focusing on children with mentally ill parents showed that after interventions including cognitive, behavioral, or psychoeducational components, the risk for the children to develop a mental disorder can be decreased by 40% [Reference Siegenthaler, Munder and Egger54]. Levey et colleagues demonstrated in a meta-analyses that the risk for child maltreatment in high-risk families, including maternal mental illness and substance abuse and IPV, can be decreased significantly by regular home-visiting, whereas there is a lack of evidence for other interventions [Reference Levey, Gelaye, Bain, Rondon, Borba and Henderson55]. These studies point out that interventions targeting ACEs linked to household dysfunctions can be effective.

Nevertheless, to design specific, targeted programs, there is a need to identify the pivotal mechanisms leading to the deleterious consequences of household dysfunction. The present analyses reveals a significant mediation of child maltreatment for the association between all assessed forms of household dysfunction and mental health, life satisfaction and self-rated health condition. These results underline the pivotal role of child maltreatment on various outcomes later in life and implies that effective interventions for families with household dysfunction need to ensure child protection as a priority. As age under 4 years is not only a known risk factor for maltreatment [Reference Jackson, Kissoon and Greene56] - but also an age period that is particularly vulnerable [Reference Green, Tzoumakis, McIntyre, Kariuki, Laurens and Dean57, Reference Cicchetti58] - interventions should start as soon as possible, e.g. during pregnancies.

However, only the long-term consequences to mental and general health of IPV and incarceration of a household member were mediated completely by maltreatment. The other consequences were mediated only partly. Therefore, other factors seem to be relevant as well. Next to maltreatment, the interaction of parents to the child are known to impact the development of children enormously [Reference World Health Organization8]. The experience of IPV was shown to affect the attachment style of mothers massively [Reference Levendosky, Bogat and Huth-Bocks14], which again is known to affect children [Reference Murray, Fiori-Cowley, Hooper and Cooper59]. In mothers with depression, the attachment style was shown to mediate the association between mothers psychopathology and child's emotional responsiveness [Reference Widom, Czaja, Kozakowski and Chauhan15]. Furthermore, parenting skills and parent-child interactions, that are known to be impaired in mothers who have experienced IPV [Reference Levendosky, Bogat and Huth-Bocks14], in mentally ill [Reference Widom, Czaja, Kozakowski and Chauhan15] and substance abusing parents [Reference Kelley, Lawrence, Milletich, Hollis and Henson16], are discussed, just as biological and socioeconomic factors [Reference Goodman19, Reference van Santvoort, Hosman, Janssens, van Doesum, Reupert and van Loon20].

4.1 Limitations

Nevertheless, there are some limitations to consider. The here shown results for ACEs are based on a retrospective self-report. In all retrospective analyses, there is a potential for underreporting due to recall bias. This can be the result of denial, embarrassment and misunderstanding [Reference Gilbert, Widom, Browne, Fergusson, Webb and Janson60, Reference Fergusson, Horwood and Woodward61] and to a potential underestimation of the here shown results. Another limitation is that the age of the subject at the time of maltreatment was not assessed. Teicher and colleagues were able to show that not only the type, but furthermore the timing of maltreatment in different development stages is relevant for the long-term consequences of maltreatment [Reference Schalinski, Teicher, Nischk, Hinderer, Müller and Rockstroh62, Reference Teicher, Anderson, Ohashi, Khan, McGreenery and Bolger63]. Moreover, as this is an observational study with a cross-sectional approach, causality cannot be deduced. However, the presented results give a meaningful insight into the relevance of child maltreatment for the comprehensive consequences of household dysfunction.

5. Conclusion

The present analysis demonstrates that the occurrence of substance abuse and mental illness of any household member, violence against the mother, incarceration of a household member and parental separation during childhood is associated with an increased risk for all subtypes of child maltreatment and moreover, that the assessed deleterious consequences of household dysfunction are mediated by child maltreatment. These results underline the role of prevention of child maltreatment in families with household dysfunction and implies child protection as an integral part of any intervention. As children under the age of 4 years are not only particularly vulnerable for maltreatment, but also for its consequences, early screenings of families with known household dysfunctions are recommendable. This requires comprehensive cooperation between different agencies, such as child protection services, law enforcement, healthcare and welfare.

Funding

Not applicable.

Compliance with ethical standards

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee of the University Leipzig and with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

VC, OB, AW, CS, EB and BS state that they have no conflict interests.

JMF has received research funding from the EU, DFG (German Research Foundation), BMG (Federal Ministry of Health), BMBF (Federal Ministry of Education and Research), BMFSFJ (Federal Ministry of Family, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth), German armed forces, several state ministries of social affairs, State Foundation Baden-Württemberg, Volkswagen Foundation, European Academy, Pontifical Gregorian University, RAZ, CJD, Caritas, Diocese of Rottenburg-Stuttgart. Moreover, he received travel grants, honoraria and sponsoring for conferences and medical educational purposes from DFG, AACAP, NIMH/NIH, EU, Pro Helvetia, Janssen-Cilag (J&J), Shire, several universities, professional associations, political foundations, and German federal and state ministries during the last 5 years. Every grant and every honorarium has to be declared to the law office of the University Hospital Ulm. Professor Fegert holds no stocks of pharmaceutical companies.

PLP has received research funding from the Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte, BMBF (Federal Ministry of Education and Research), VW-Foundation, Baden-Württemberg Stiftung, Lundbeck, Servier. Professor Plener holds no stocks of pharmaceutical companies.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.