Introduction

Periodic elections, topped with some basic liberties that ensure their competitiveness, lie at the core of most definitions of democracy (Dahl, Reference Dahl1971; Schumpeter, Reference Schumpeter1976). Free and fair elections, the rule of law, or the existence of some basic liberal rights are, therefore, essential constitutional guarantees that ensure that the people can rule (Fuchs, Reference Fuchs and Norris1999). As such, modern democracies are unthinkable without the presence of these attributes. However, beyond these common minimal elements, democracies can be institutionalized in different ways in order to realize the ideal of ‘rule by and for the people’ through competitive elections (Held, Reference Held2006; Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012).

The distinction between consensus and majoritarian political systems constitutes one of the main divides in how democracies are institutionalized (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012). While the former disperses power among different groups, the latter concentrates it in the hands of the majority. In consensus democracies, decisions are legitimate because they are reached through collegial decision-making, bargaining, and compromise. In majoritarian systems, instead, decisions are legitimate because they reflect the will of the majority and those responsible for these decisions can be clearly identified. Hence, consensual systems emphasize and facilitate representation and responsiveness to as many points of view as possible, while majoritarian systems emphasize and facilitate government mandate and accountability (Powell, Reference Powell2000). Therefore, the choice between a consensual and majoritarian political system involves a trade-off between multiple desirable features of democracies (Powell, Reference Powell2000:19). In other words, while features such as responsiveness, representation, mandate, and accountability are all normatively desirable, they cannot be simultaneously maximized evenly (Bochsler and Kriesi, Reference Bochsler, Kriesi, Kriesi, Bochsler, Matthes, Lavenex, Bühlmann and Esser2013). All constitution makers are forced to make a choice and prioritize some features over others.

In this paper, we focus on the preferences of individuals about this essential democratic trade-off. Specifically, we analyze whether Europeans believe that a consensus or majoritarian political system is best for democracy, and how the type of democracy they endorse might be explained by factors related to institutional learning and the position one holds in the political system.

Starting from the assumption that political institutions can shape political attitudes (Mishler and Rose, Reference Mishler and Rose2001), we first propose that beliefs about the best model of democracy are influenced by citizens’ exposure to particular forms of governance. A democratic nation’s constitutional arrangements and institutional framework provide citizens with a frame of reference to interpret and understand political reality (Almond and Verba, Reference Almond and Verba1963). Therefore, individuals’ continuous exposure and experience with a particular democratic system should instill beliefs that are aligned with that specific model of democracy (Heyne, Reference Heyne2019; Rohrschneider, Reference Rohrschneider1999). This institutional learning mechanism should give rise to stable (long-term) cross-country differences in citizens’ preferences about consensus and majoritarian democracy.

In the short run though, these preferences might be altered by changes in the political circumstances of individuals. Studies have consistently shown that being an election ‘winner or loser’ affects individuals’ attitudes toward democracy, mainly their satisfaction with how democracy works (see e.g., Anderson and Guillory, Reference Anderson and Guillory1997; Bernauer and Vatter, Reference Bernauer and Vatter2012; Leiter et al., Reference Leiter, Clark and Clark2019). Similarly, in the case of preferences about the type of democracy, we propose that individuals’ standing as an electoral minority or majority should affect their beliefs about whether a consensual or majoritarian system is the best way in which a democracy can be institutionalized. Whether these long- and short-term factors prevail in influencing these preferences about the best model of democracy should be a function of the length of democratic ruling in each country, though.

We test these arguments drawing on data from the sixth (2012) round of the European Social Survey (ESS), which included a rotating module on citizen’s views and evaluations of democracy (Ferrín and Kriesi, Reference Ferrín and Kriesi2016). We analyze individuals’ preferences for a majoritarian or consensus type of democracy by assessing whether they believe that single-party governments or coalition governments are best for democracy. Whether governments are formed by one or more parties is a prototypical characteristic of political systems that epitomizes most of the trade-offs between the consensual and majoritarian models of democracy (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012:79; Powell, Reference Powell2000). Even if this measure does not account for all the differences between these two models of democracy, we would argue that it is yet an adequate way to proxy citizens’ preferences through a direct and easily understandable survey question (see below).

Our analyses reveal that Europeans overwhelmingly think that a consensus political system is the best model of democracy. However, these preferences are strongly influenced by the institutional makeup of each country. The position of each country in Lijphart’s executive-parties dimension is strongly related to these preferences. Those living in majoritarian systems are more likely to think that the best model of democracy is one in which government power is concentrated in the hands of the majority, while those living in more consensual systems are likely to express a stronger preference for coalition governments. Individuals’ position as an electoral majority or minority is also relevant to explain within country variation in these preferences. Those who are part of the political minority, as measured by the fact that they support smaller parties, are more supportive of consensus democracy, while those who vote for large parties tend to think that majoritarian systems are best for democracy. However, our analyses also reveal that the relevance of each of these factors in influencing these preferences is moderated by the democratic trajectory of each country.

Learning and experiencing democracy: long- and short-term preferences

Democracy is not one and the same, and there is extant evidence that citizens have defined preferences (or expectations) about democracy and the type of democracy they want (see e.g., Bengtsson and Mattila, Reference Bengtsson and Mattila2009; Ceka and Magalhães, Reference Ceka, Magalhães, Ferrín and Kriesi2016; Hernández, Reference Hernández2019; Linde and Peters, Reference Linde and Peters2018; Schedler and Sarsfield, Reference Schedler and Sarsfield2007). When it comes to basic elements of democracy such as free and fair elections, the rule of law, or basic liberal rights, most Europeans share similar preferences (Hernández, Reference Hernández, Ferrín and Kriesi2016a). In line with the essential role that these elements play in all democracies, most citizens across Europe consider that these are fundamental features of this political system. However, this might not be the case for those elements which can be institutionalized in different ways. Therefore, while most citizens consider that free elections and basic liberties are fundamental characteristics of democracies (Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Shin, Jou, Diamond and Plattner2008), the extent to which citizens endorse a consensual or majoritarian type of democracy should present greater variation. However, there is a paucity of evidence about citizens’ preferences for majority and consensus democracies and, especially, on the reasons why people endorse these different models of democracy (cf. Heyne, Reference Heyne2019).

When it comes to the majoritarian–consensus trade-off, normative and empirical analyses of democracy do not provide us with clear cues as to which of these models of democracy individuals might favor. Each of these models is satisfactory on its own terms: majoritarian models generating clarity of responsibility and accountability, and consensual systems promoting broad representation and responsiveness (Powell, Reference Powell2000). Some empirical studies indicate, though, that consensus democracies are still superior, since they outperform majoritarian systems when it comes to the quality of democracy and representation, and they also promote the implementation of ‘kinder and gentler’ policies (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012). However, at the same time, majoritarian political systems might be more appealing to citizens since the idea of policymaking being responsive to the will of the majority might appear to be, in principle, closer to the democratic ideal of ‘rule by the people’ (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012). Moreover, majoritarian systems might also appear more effective since they can avoid lengthy processes of government formation that might end up in legislative or governmental gridlock situations. We, therefore, expect to find variation in citizens’ beliefs about which of these models is best for democracy, and that this variation will be explained by the model of democracy implemented in each country and the position individuals’ hold in the political system.

Simple enough, people learn from what they experience. Transitions to democracy in Eastern Europe in the 90s provided a quasi-experimental field to test this proposition, as people gradually adopted democratic values (Fuchs and Roller, Reference Fuchs and Roller2006; Mishler and Rose, Reference Mishler and Rose2001, Reference Mishler and Rose2002) or opposed them (Pop-Eleches and Tucker, Reference Pop-Eleches and Tucker2014). The so-called model of institutional learning proposes that the institutional makeup of a country shapes the values and orientations toward democracy of its citizens (Rohrschneider, Reference Rohrschneider1999). Interacting with a given model of democracy gives citizens the opportunity to learn and internalize the prevailing norms of that particular political system. These institutional learning theories that were initially developed and tested in postcommunist countries have proven useful elsewhere. Attitudes such as political tolerance (Peffley and Rohrschneider, Reference Peffley and Rohrschneider2003) or democratic knowledge (Norris, Reference Norris2011) develop in long-living and stable democracies around the world (see also Mattes and Bratton (2007)). However, except for Heyne (Reference Heyne2019) and Franklin and Riera (Reference Franklin, Riera, Ferrin and Kriesi2016), there is a paucity of evidence about the influence of democratic institutions on citizens’ preferences for particular models of democracy, other than general attitudes toward democracy (i.e., support and satisfaction with democracy in the abstract).

It is yet reasonable to think, following Rohrschneider’s (Reference Rohrschneider1999) argument, that institutional learning occurs in relation to all facets of the democratic process, and especially in the case of relevant elements and principles that can be implemented in different ways across political systems. The way in which constitution makers respond to essential trade-offs by prioritizing some desirable features of democratic processes over others shapes the character of each democracy, as well as the structure of political conflict within each political system. This is especially so for the consensus–majoritarian trade-off, which implies that ‘citizens of different political systems are exposed to different political processes and ideals’ (Rohrschneider, Reference Rohrschneider1999: 16–17). Footnote 1 Take as an illustration those countries that can be considered prototypes of each of these models of democracy: the UK for the majoritarian model and Switzerland for the consensual one. These countries’ identity as a democratic nation is built around the majoritarian or consensual nature of their institutions. Citizens are constantly exposed to the specificities of each of these models of democracy, and most of their interactions with their political system are shaped by constitution makers’ decisions to implement a political system that either concentrates power in the hands of the majority or disperses it among multiple social groups. In each system, citizens are constantly exposed to the norms, values, and procedures underlying the majoritarian or consensual nature of their democracy, as well as to the outcomes these institutions lead to. Following this institutional learning logic we, therefore, expect that:

HYPOTHESIS 1: In consensual political systems citizens will prefer a consensus democracy; in majoritarian systems citizens will prefer a majority democracy.

Individuals are yet not identical, but rather the position one holds within the political system is likely to influence the way one perceives or even experiences democracy, and consequently one’s democratic preferences. Levels of education, for example, have been shown to influence an individual’s preferences for representative, stealth, and direct democracy in the Netherlands (Coffé and Michels, Reference Coffé and Michels2012), Finland (Bengtsson and Mattila, Reference Bengtsson and Mattila2009), and, more generally, Europe (Ceka and Magalhães, Reference Ceka, Magalhães, Ferrín and Kriesi2016). Whereas the lowest educated tend to give stronger support to direct or stealth democracy than to representative democracy, the highly educated have clear preferences for representative democracy. Most relevant for our purposes, individuals’ political circumstances also have an impact on their attitudes toward democracy, as the ‘winners’ of an election tend to be more satisfied with democracy than the ‘losers’ (Anderson and Tverdova, Reference Anderson and Tverdova2001). Rosset et al. (Reference Rosset, Giger and Bernauer2017), in fact, find that citizens’ preferences about the ideal type of representation are related to the potential policy gains they expect to get from government. As such, individuals who perceive that their ideological position is well represented by the incumbent government are more in favor of a trustee model of representation, while the ‘median voters’ are more in favor of a mandate model of representation.

People’s preferences are therefore influenced by: (i) whether they perceive that they belong to ‘the majority’ or to ‘a minority’ and (ii) which type of democratic system they think is better able to protect their interests as part of the majority or a minority. The choice between consensus and majority democracy clearly points to the core of this concern. Since majority democracies make it difficult for small parties to be in government, it is likely that individuals who support small parties will prefer consensus democracy; whereas individuals who support big parties will prefer majority democracy. From a rational and self-interested perspective, voters of small parties are likely to be better off in consensual systems, since they are more likely to see their preferred government and policies implemented. Conversely, the political preferences of voters of large parties are more likely to be maximized in majoritarian systems. This process is likely to be reinforced by the cues provided by political parties’ own interpretations of their standing in each political system. Depending on their electoral success, and their odds of becoming an incumbent, political parties take particular stances on the country’s democratic performance (Rohrschneider and Whitefield, Reference Rohrschneider and Whitefield2019). This might influence their voters’ perceptions of belonging to the political ‘minority’ or ‘majority’, and, ultimately, their attitudes toward democracy. We, therefore, expect that:

HYPOTHESIS 2: The smaller the vote share of the party an individual supports, the stronger her preference for consensus democracy.

H1 and H2 propose two complementary explanations for the formation (and change) of individuals’ preferences about democracy. However, while the institutional context is a permanent feature of political systems, the position of an individual as a political majority or minority might change from one election to another. Context is therefore likely to shape citizens’ long-term preferences, whereas an individual’s majority/minority position is likely to influence short-term preferences for consensus vs. majority democracy. Footnote 2

The length of a given country’s democratic experience will probably determine whether long- or short-term factors prevail. Previous studies have shown that the age of a democracy (i.e., the number of years a country has been uninterruptedly democratic) is significantly related to positive attitudes toward democracy and higher levels of democratic awareness (Norris, Reference Norris2011; Booth and Seligson, Reference Booth and Seligson2009). As such, citizens in long-living democracies might also be more likely to conform with the institutional setting than citizens in relatively new democracies, especially if it preserves the status quo (Ceka and Magalhães, Reference Ceka, Magalhães, Ferrín and Kriesi2016). That is, institutional learning should be more effective, the more consolidated a democratic system is (Rohrschneider, Reference Rohrschneider1999). Therefore, preferences for consensus vs. majority democracy should be more stable in old democracies as compared to new democracies, since, in the latter, citizens have had less time and opportunities to directly experience and learn about the political institutions that will shape their preferences. In other words, long-term factors related to institutional learning should be more influential in established democracies. We, therefore, hypothesize that

HYPOTHESIS 3: The older a democracy, the stronger is the relationship between the institutional setting (as consensus/majority) and the citizen’s preferences about consensus/majority democracy.

Conversely, in countries without a prolonged democratic experience, we might expect short-term factors to be more influential. In these contexts, citizens have been less exposed to the particular constitutional features of their democracies. Following a lifetime institutional learning model, which proposes that political lessons are learnt and reinforced over time throughout one’s life, we, therefore, expect that the influence of the institutional context on citizens’ understandings of democracy will be weaker in younger democracies (Mishler and Rose, Reference Mishler and Rose2007). Hence, short-term factors will play a more relevant role in these countries. In young political systems, where institutions are less likely to anchor citizens’ preferences, citizens should be guided to a larger extent by their own political position as an electoral minority or majority.

Previous studies, in fact, argue that being an election winner or loser could be more relevant for individuals’ attitudes toward democracy in young democracies than in more established ones (Anderson and Tverdova, Reference Anderson and Tverdova2001). This is because, in established democracies, through repeated experience, minorities might better understand that their position can, at some point, change. Similarly, in long-lasting democracies, political parties ‘can rely on memories of victory in defeat’, which make parties’ regime evaluations less dependent on whether they win or lose a given election (Rohrschneider and Whitefield, Reference Rohrschneider and Whitefield2019, 361). These arguments lead us to expect that attitudes toward democracy will be less influenced by the electoral majority/minority position of individuals in more established democracies. Hence, individuals’ political positions as an electoral majority or minority will have a stronger impact on citizens’ preferences about consensual and majoritarian democracy in young democracies than in contexts with a prolonged democratic experience. In other words, we hypothesize that

HYPOTHESIS 4. The older a democracy, the weaker is the relationship between the position of an individual as an electoral majority or minority and her preferences for consensus vs. majority democracy.

Data and methods

The empirical analyses of this paper draw on data from the sixth round of the ESS conducted between 2012 and 2013 in 29 European countries (ESS, 2012). We combine this individual-level data with information on election results from the ParlGov database (Döring and Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2019) and information on countries’ institutional characteristics from the Comparative Political Data Set (CPDS) (Armingeon et al., Reference Armingeon, Isler, Knöpfel, Weisstanner and Engler2016). As a result of merging these datasets, the final sample considered in this paper is limited to 24 countries. Footnote 3

We measure preferences for a consensus or majoritarian model of democracy through a question that directly asks respondents whether they think that a political system in which ‘A single party forms the government’ or in which ‘Two or more parties in coalition form the government’ is best for democracy in general. Footnote 4 The question is posed in a forced-choice or trade-off format, since respondents were asked to choose which of the two types of government they think is best for democracy. Footnote 5 This question format is particularly adequate when not all respondents have an overall basic acceptance of the concept being asked (e.g., majoritarian democracy), but, instead, there are two clearly defined (and antagonistic) positions respondents can side with (Winstone et al., Reference Winstone, Widdop, Fitzgerald, Ferrín and Kriesi2016). This formulation reflects the idea that the desirable features of consensus and majoritarian democracy cannot be simultaneously maximized. The resulting measure of consensus–majoritarian democracy preferences takes the value 0 for those who think that a single party is best for democracy and the value 1 for those who think that it is best if the government is formed by two or more parties. Footnote 6

The divide between coalition and one-party cabinets is theoretically (and empirically) the most relevant dimension of the consensus–majoritarian trade-off (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012: 79, 242). This divide epitomizes the contrast between majoritarian democracies’ concentration of powers and the division and power-sharing that characterizes consensual ones (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012: 79). However, our measure does not directly account for preferences related to other characteristics of the consensus–majoritarian divide, such as, for example, the type of electoral system, the rigidity of constitutions, or executive dominance. A latent measure based on multiple indicators that capture the multidimensionality of the divide might be more appropriate. Hence, since some countries might have a long tradition of single-party government, and yet characterize principally as consensus democracies, our dependent variable just provides a conservative estimate of citizens’ preferences for consensus/majoritarian democracy and how it is influenced by the context where citizens live. One must take into account this limitation when interpreting the results.

To measure if countries implement a consensual or majoritarian model of democracy, we rely on data from the CPDS. We assign each respondent the value of Lijphart’s parties-executives (or first) dimension of her own country. This variable takes lower values for countries that are closer to the majoritarian pole and higher values for countries that are close to the pure consensual model. The index is based on the moving average (10 years) of the following variables: the effective number of parties in parliament, the absence of minimal winning and single-party majority cabinets, the proportionality of the electoral system, and a measure of cabinet dominance (see Armingeon et al., Reference Armingeon, Isler, Knöpfel, Weisstanner and Engler2016:65). As such, this measure combines both institutional features (electoral rules) and elite behavior that is promoted by these features (coalition building and cabinet dominance). This variable ranges between −2.43 and 2.07, and our sample includes prototypical cases of majoritarian (UK) and consensual democracies (Switzerland). Although this variable only partially taps into the institutional features of majoritarian and consensus models of democracy, the party system features included in this measure are among the most relevant dimensions of the consensus–majoritarian trade-off (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012: 242). Moreover, for our purposes, this country-level variable has the advantage of matching relatively well to our dependent variable, which asks respondents to express their preferences for single-party or coalition governments.

To operationalize the position respondents hold in the political system, specifically their position as an electoral minority or majority, we rely on the vote share of the party respondents voted for in the last election. Using data on election results from the ParlGov database, we assign to each respondent a value that corresponds to the vote share of the party they voted for in the last national election held before the fieldwork of the ESS. Bulgaria represents an exception to this operationalization, since in that case the ESS asked about the presidential and not the parliamentary election, and it is not entirely clear if they asked about the first or second round of the presidential election. Therefore, in this case, we assign respondents the vote share of the party they feel closer to.Footnote 7 For those countries not available in the ParlGov database, we relied on official sources to obtain the vote share of parties. The resulting variable ranges from 0.1 to 52.7 percent and excludes those respondents who either did not vote in the last national election or who do not provide information about the party they voted for.

To operationalize countries’ experiences of democracy, we rely on data from Polity IV. Specifically, the historical experience of democracy variable reflects the number of years that a country has uninterruptedly been democratic (values above 6 in the Polity IV index) between its last transition to democracy and 2012.

Our dependent variable measuring citizens’ preferences for majoritarian vs. consensus democracy takes the values 0 and 1. All our estimations are, therefore, based on random intercepts multilevel logistic models. All our models include controls for whether or not respondents voted for a cabinet party (based on the ParlGov database), feel close to any political party, are citizens of the country they live in, or belong to an ethnic minority, with the value 1 indicating that they do and the value 0 that they do not. We also control for their levels of trust in political parties (measured from 0 to 10). All models also control for three basic sociodemographic characteristics of respondents: their age, gender, and level of education.

In addition, we control for two variables related to the political system’s output and performance. First, we use the World Bank Governance Indicators 2012 to generate a proxy measure of the quality of democracy in each country, which we operationalize as a composite index of three dimensions closely related to democratic performance: accountability and voice, level of corruption, and government effectiveness. For each country, we compute the average of these indicators in a variable that ranges between −0.80 and 2.02, with higher values indicating a higher quality of democracy.Footnote 8 Second, to control for economic development and performance in all our models, we control for countries’ GDP per capita (measured in euros).

Results

In our sample of 24 European countries, a clear majority of citizens think that a consensual political system is best for democracy. Overall, 77 percent of respondents believe that the best model of democracy is one in which governments are formed by coalitions of two or more parties, and just 23 percent of respondents think that democracies would be better served by single-party governments. Footnote 9 Considering that our dependent variable provides a conservative estimate of citizens’ preferences about majoritarian–consensus democracy, it is outstanding that a majority of Europeans clearly prioritize one of the main features of consensus democracy.

Figure 1 summarizes the proportion of citizens supporting a consensus model of democracy by country. The data reveal a strikingly high support for a consensus model of democracy in most countries. In four countries (Switzerland, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Finland), more than 90 percent of its population think that coalition governments are best for democracy. Conversely, only in two countries, Portugal and the UK, citizens appear to favor a majoritarian model instead of a consensual one. In any case, when analyzing this data country by country, we find great differences between them. For example, in the UK, most citizens (66 percent) favor a majoritarian model of democracy. In Switzerland, instead, an overwhelming 97 percent of respondents think that a consensual political system is best for democracy. It is hardly a coincidence that these two countries are the prototypical cases of majoritarian and consensus democracies, respectively. This provides some preliminary, and anecdotal, support for our first hypothesis. However, at the same time, there are also some significant differences in citizens’ average preferences between countries that take similar values in Lijphart’s parties-executive dimension (see Figure A3 in the Online Appendix). Take as an example the cases of France and Portugal. These two countries have a similar value in Lijphart’s index of consensus–majoritarian democracy. However, while in France 73 percent of citizens support consensus democracy, in Portugal only 48 percent do so. This suggests that there are factors beyond institutional learning that influence these preferences.

Figure 1. Proportion of respondents supporting consensus democracy by country.

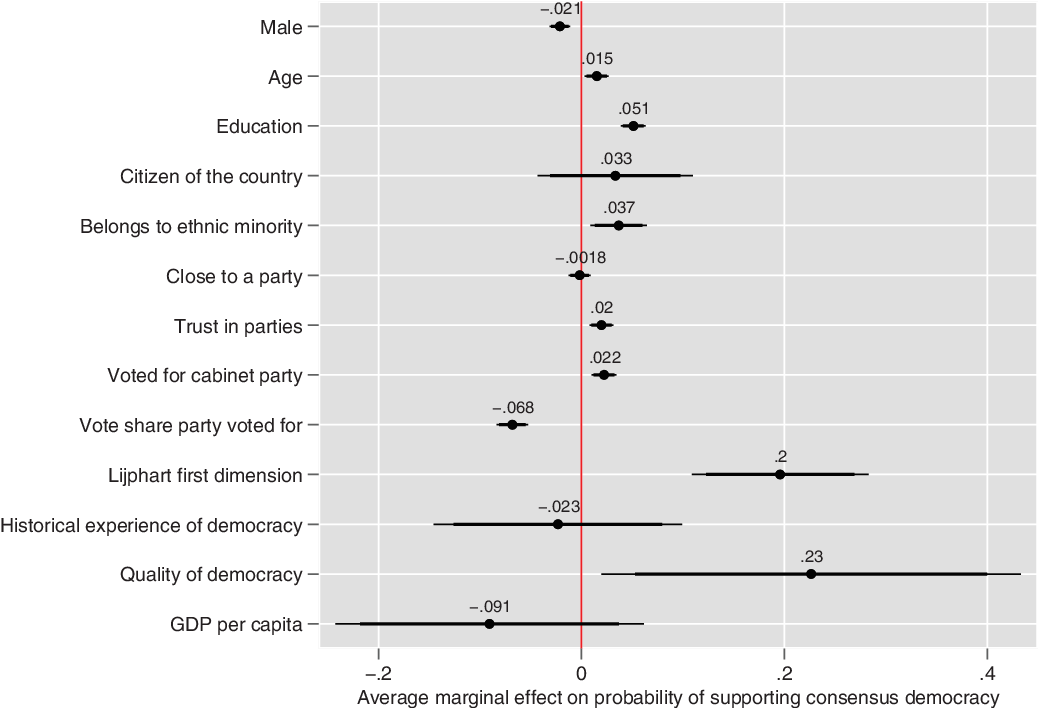

We now turn to examine the role played by institutional learning and individuals’ political position as an electoral minority or majority. For this purpose, we fit a random intercepts multilevel logistic model that includes all of our individual and country-level variables. The results of this model are summarized in Table A1 in the appendix (model 1). To facilitate the interpretation of the results, in Figure 2, we plot the average marginal effect of each of the predictors. Positive/negative values indicate that the covariate increases/decreases the probability of thinking that a consensual system is the preferable model of democracy. For this summary of the results, all numeric predictors have been mean centered and standardized, so that their coefficients represent the effect of a two standard deviation change and can be compared among themselves and to untransformed categorical predictors (Gelman, Reference Gelman2008).

Figure 2. Average marginal effects on probability of supporting consensus democracy.

Note: Based on Model 1 Table A1 (online Appendix). Thick and thin lines are 90 and 95 percent confidence intervals, respectively. All plots are generated using Bischof’s (Reference Bischof2017) plottig scheme.

When it comes to the control variables, we observe that being older, more trustful of political parties, and more educated increases the likelihood of thinking that a consensus political system is best for democracy. Congruent with our argument about the potential mechanisms underlying citizens’ democratic preferences, belonging to an ethnic minority also increases the likelihood of preferring a consensus over a majority democracy. Having voted for a party that has seats in the cabinet also increases the probability of supporting a consensus model of democracy, although the magnitude of this effect is relatively small. Conversely, males are slightly more likely to embrace a majoritarian model of democracy than females. The effects of being a citizen of the country or being close to a particular political party are not distinguishable from zero. Moreover, while a country’s historical experience of democracy or its GDP per capita are not significantly associated with these preferences, the quality of its democracy does appear to increase the probability of supporting a consensus model.

Focusing on our first variable of interest, the results reveal that preferences about majoritarian–consensus democracy are strongly related to the model of democracy implemented in the respondent’s country. A two-standard deviation move toward the consensual pole in Lijphart’s first dimension increases the probability of thinking that a consensus political system is best for democracy by 20 percent. This is, by far, one of the strongest predictors of our model.

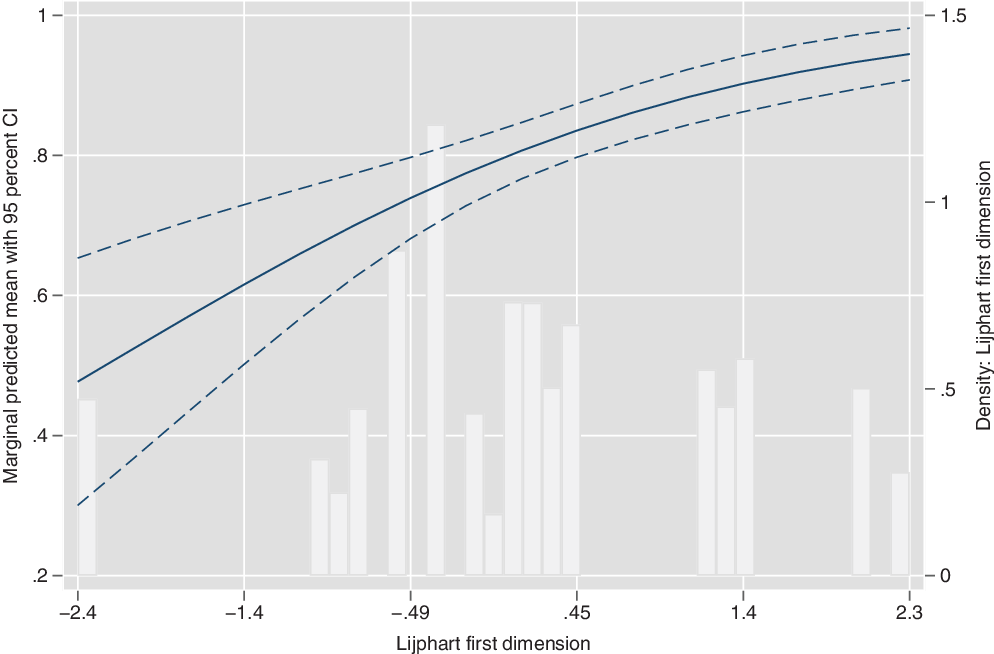

This relationship is summarized in Figure 3, which plots the predicted support for consensus democracy along the values of Lijphart’s executives-parties dimension (the histogram in the background summarizes the distribution of this variable). The average probability of thinking that the ideal model of democracy is one in which governments are formed by more than one party increases from 0.47 in the most majoritarian countries to 0.94 in the most consensual political systems. Even when excluding the most majoritarian country from the sample (the UK), our analyses still reveal a strong positive relationship between countries’ locations in Lijphart’s first dimension and citizens’ support for consensus democracy (see Figures A1 and A2 in the Online Appendix).

Figure 3. Predicted support for consensus democracy along Lijphart’s parties-executive (first) dimension.

Note: Based on Model 1 Table A1 (Online Appendix). All marginal effects plots are generated with Hernández’s (Reference Hernández2016b) marhis package.

These results are clearly in line with our institutional learning hypothesis (H1). Citizens appear to favor a model of democracy that is aligned with the one implemented in their country. However, there are clear differences in this regard between those who live in consensus and majoritarian democracies. Citizens who live in prototypical consensus democracies (e.g., Switzerland or Belgium) overwhelmingly, and almost universally, support this model of democracy. However, in countries with prototypical majoritarian institutions (e.g., the UK), citizens are less enthusiastic about their own model of democracy. While in these countries a majority still thinks that the best model of democracy is a majoritarian one, its population is much more divided. For example, in the UK, a sizable proportion of citizens (around 35 percent) think that the best model of democracy is a consensual one.

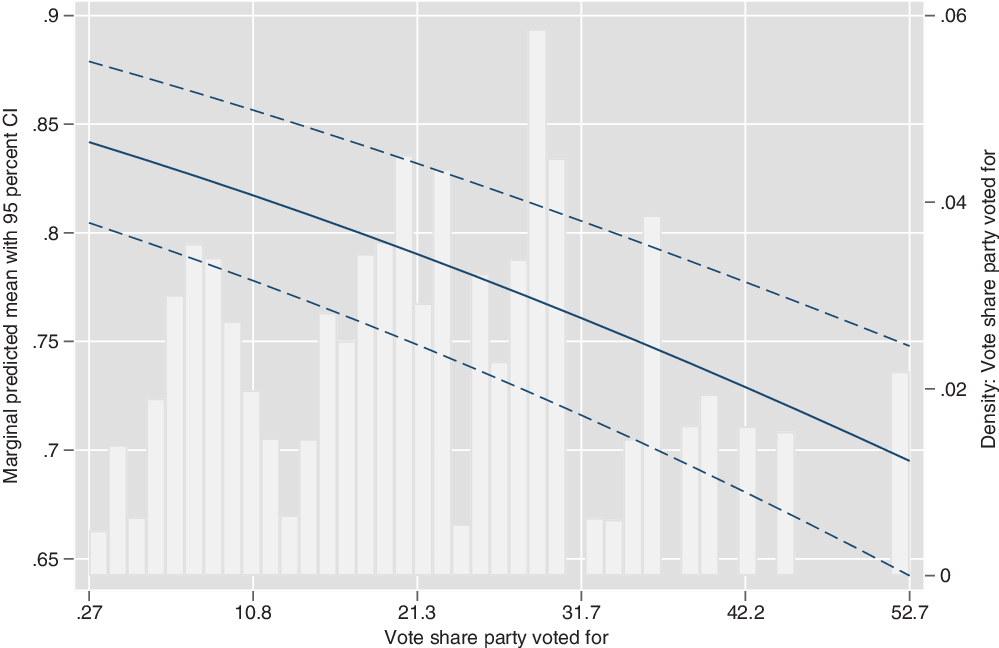

To assess the role that individuals’ position as an electoral minority or majority plays for preferences about majoritarian–consensus democracy, we include in our models a variable measuring the size (vote share) of the party respondents voted for. The negative marginal effect of this variable, summarized in Figure 2, indicates that the higher the vote share of the party an individual has voted for, the lower the probability that she thinks that the ideal model of democracy is a consensual one. A two-standard deviation increase in the vote share of the party voted for in the last election (equivalent to a 24 percent increase in such vote share) reduces the likelihood of thinking that a consensual system is the best model of democracy by 6.8 percent. In comparison to other individual-level predictors included in our model, this is a substantial change. For example, the impact of the vote share of the party one votes for is substantively stronger than the effect of belonging to an ethnic minority and it is also greater than the effect of individuals’ level of education.

Figure 4 summarizes how the probability of thinking that consensus political systems are best for democracy changes as a function of the size of the party one votes for (the histogram in the background summarizes the distribution of the variable measuring the vote share of the party). For example, the predicted support for consensus democracy for an individual who votes for a very small party (1 percent of the vote share) equals 0.84, while this support among someone who votes for a party that obtains half of the vote share equals 0.7. These results, which are in line with our second hypothesis, indicate that a person’s position as a political majority or minority is a relevant correlate of the model of democracy she supports. In line with the idea that political minorities are likely to be better off in consensual systems, being a voter of a small party substantially increases the likelihood of thinking that the best model of democracy is a consensual one.

Figure 4. Predicted support for consensus democracy as a function of the size of the party voted for.

Note: Based on Model 1 Table A1 (Online Appendix).

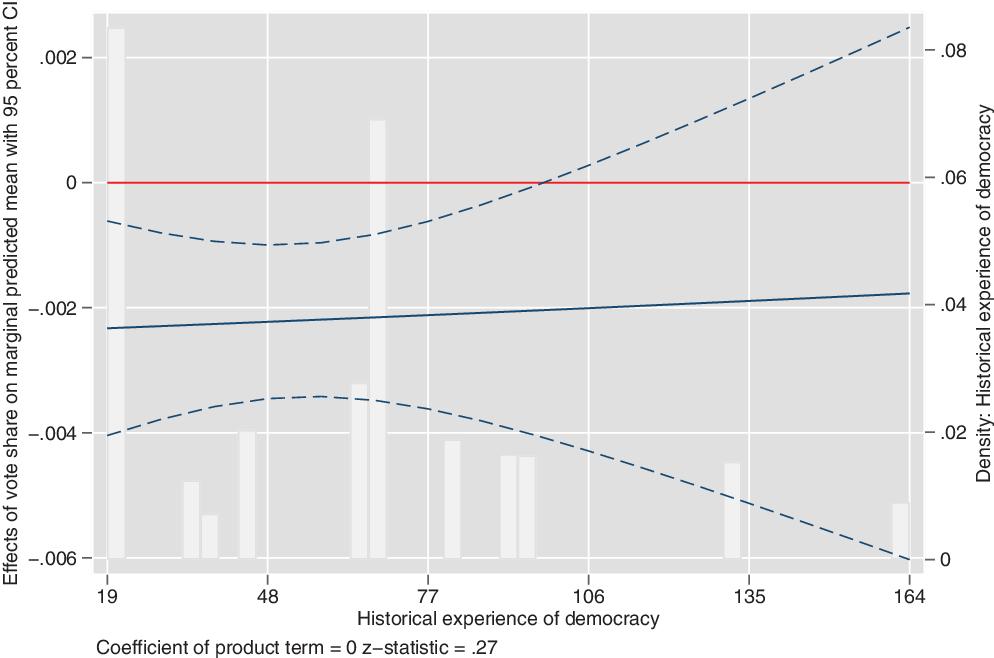

We now examine to what extent the importance of long-term factors related to institutional learning and short-term factors related to individuals’ majority/minority position are moderated by the historical experience of democracy of each country. For this purpose, we first fit a random intercepts multilevel logistic model (model 2 of Table A1 in the Appendix) that includes an interaction between the countries’ position in Lijphart’s first dimension and their historical experience of democracy. Figure 5 summarizes the results of this interaction by plotting the average marginal effect of a one-unit increase in Lijphart’s first dimension along the range of the variable measuring the countries’ historical experience of democracy. These results indicate that institutional learning appears to be more relevant in consolidated democracies. In line with H3, the older the democracy, the stronger the relationship between a country’s position in Lijphart’s first dimension and individuals’ preferences about consensus–majoritarian democracy is. Footnote 10 In other words, living in a consensus or majoritarian system appears to be more influential in shaping citizens’ beliefs about the ideal model of democracy in long-established democracies. As predicted by institutional learning theories, in these contexts, citizens’ ideals of democracy are more closely aligned with the institutional makeup of their countries. In fact, it is only in countries that have uninterruptedly been democratic for more than 59 years that there is a statistically significant relationship between their position in Lijphart’s first dimension and citizens’ democratic preferences. For example, in a country that has been uninterruptedly democratic for 30 years, a one-unit increase in Lijphart’s first dimension just leads to a 0.007 increase in the probability of preferring a consensus democracy, and this effect is not statistically significant. Instead, in a country that has been democratic for 90 years, this marginal effect equals 0.092, and the effect is statistically significant at conventional levels. Footnote 11

Figure 5. Effects of a one-unit increase in Lijphart first dimension along countries’ historical experiences of democracy.

Note: Based on Model 2 Table A1 (Online Appendix).

Our theoretical framework proposes that in those countries with a less prolonged democratic experience, short-term factors related to individuals’ minority/majority position should, instead, be more relevant (H4). To test this hypothesis, we specify an additional random intercepts and random slopes multilevel logistic model (model 3 in Table A1) that includes a cross-level interaction between the vote share of the party respondents’ voted for and the historical experience of democracy of each country. Footnote 12 The results of this interaction, which are summarized in Figure 6, clearly refute our fourth hypothesis. While in younger democracies the minority/majority position of individuals appears to be slightly more influential, the difference in the marginal effect of the vote share of the party voted for between the youngest and the most established democracies is very limited. Footnote 13 In fact, the cross-level interaction coefficient is not statistically significant at conventional levels (p-value = 0.791). Footnote 14 However, it is also worth noting that the results summarized in Figure 6 reveal that in the oldest democracies the effect of the vote share of the party individuals’ vote for is not statistically significant at conventional levels.

Figure 6. Effects of a 1-unit increase in the vote share of the party voted for along countries’ historical experiences of democracy.

Note: Based on Model 3 Table A1 (Online Appendix).

Overall, the results summarized in Figures 5 and 6 reveal some theoretically relevant differences in the factors that shape individuals’ preferences for a consensus or majoritarian democracy across countries. In the youngest democracies, institutional learning does not appear to have occurred yet, and individuals’ preferences are critically linked to their position as a political majority or minority. In these contexts, the political position of individuals is one of the most relevant correlates. Since in the youngest democracies citizens have had fewer opportunities to directly interact with their political institutions, it is reasonable that their impact on these preferences is weaker (institutional learning might be a cumulative process that manifests only with time). In more established democracies, instead, these preferences are shaped by a combination of institutional learning and short-term factors related to the position of individuals as an electoral majority or minority. In these contexts, citizens are much more likely to align their preferences about their ideal model of democracy with the institutional makeup of their countries but, at the same time, their position as a political majority/minority also plays a relevant role. In these established democracies, both short- and long-term factors have a relevant influence on these preferences. The exception to this pattern are the oldest democracies in our sample, where being in the majority or the minority does not appear to be significantly related to individuals’ preferences about the ideal model of democracy. However, more data at the end of the historical experience of democracy distribution would be required in order to make a definitive claim about the irrelevance of individuals’ position as an electoral minority/majority in these long-established democracies.

Conclusion

Democracies are expected to promote democratic values, which are an important ingredient for their consolidation and stability. In this article, we investigate an understudied aspect of citizens’ attitudes toward democracy: their preferences for a majoritarian or a consensus model of democracy. Using data from 24 European countries, we find that most citizens believe a consensus system is best for democracy, although there are stark contrasts across Europe in the extent to which individuals endorse this model of democracy. This is an interesting finding in and of itself, even if one must take into account that our dependent variable only captures preferences about a specific feature of the divide between majoritarian and consensual democracies. Like political theorists, citizens appear to have different opinions about consensus and majoritarian democracy, and they do not fully agree when it comes to this essential democratic trade-off. We hypothesize that these differences might be crucially shaped by institutional learning and the position of individuals as a political majority/minority.

In line with previous research, our results confirm that it is not only general principles of democracy that are learned and internalized through experience (Rohrschneider, Reference Rohrschneider1999), but also preferences about the specific implementations of democracy such as – in our case – the trade-off between majoritarian and consensus constitutional arrangements. Exposure and experience with a particular democratic system appears to instill beliefs that are aligned with that specific model of democracy. Institutional learning, therefore, occurs at all levels of the democratic process and it even influences citizens’ preferences for the particular type of democracy –majority or consensus– they endorse. Hence, like Almond and Verba (Reference Almond and Verba1963) proposed, the institutional makeup of countries seems to provide citizens with a frame of reference to interpret and understand political reality, which affects even their most basic ideas about how democracy ought to be.

While institutional learning can give rise to stable (long-term) cross-country differences in citizens’ preferences, we argue that across individuals these preferences must also vary as a function of the position of each individual as a political majority or minority. Our results indicate that people who are in the political minority are more likely to support a consensus democracy, as they might feel that their interests are better protected and represented in this system than in a majoritarian democracy, where minorities might end up being excluded from the policymaking process. Conversely, people who are part of the political majority tend to be more in favor of a majoritarian model of democracy, as they are more likely to benefit from this type of political system. Therefore, it seems that beyond institutional learning, individuals also take into account their own interests, since they tend a favor a democratic system where their preferred government and policies are more likely to be maximized. The implication of this finding is that preferences about consensus and majoritarian democracy might also vary in the short run whenever the minority/majority position of individuals changes.

Whether institutional learning or the position of individuals as an electoral majority or minority prevail in influencing citizens’ preferences about the best model of democracy could be a function of the democratic trajectory of each country, though. Our findings indicate that this is indeed the case. In young democracies, which lack a prolonged experience of democratic ruling, individuals’ preferences are hardly influenced by the institutional context, and they are, instead, closely related to the position of individuals as a political majority or minority. In contrast, in most established democracies, these preferences are shaped both by institutional learning and the position of individuals as a political majority or minority. Therefore, it appears, once again, that the more effective the institutional learning, the more consolidated the democratic system is (Rohrschneider, Reference Rohrschneider1999). However, at the same time, these findings stand in contrast with those of the party-level literature that posits that in established democracies parties’ regime evaluations might be less influenced by their electoral performance (Rohrschneider and Whitefield, Reference Rohrschneider and Whitefield2019). In the case of individuals, being part of the electoral majority or minority seems to exert a similar influence on attitudes toward democracy, independently of whether individuals live in a young or established democracy. Further research should consider whether in long-established democracies voters of small parties, which have at some point being part of winning coalitions, might be less influenced by their minority position. This is the specific case in which the mechanism of relying on past ‘memories of victory in defeat’ proposed by Rohrschneider and Whitefield (Reference Rohrschneider and Whitefield2019) might be at play.

All in all, though, the broader implication of these findings is that preferences about consensus and majoritarian models of democracy will be more stable in long-established democracies, since in these contexts, preferences are anchored to a greater extent by the institutional makeup of each country. In young democracies, instead, we might see greater changes and fluctuations in individuals’ preferences, since their position as an electoral minority or majority might change from one election to the next.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773921000047.

Acknowledgments

This research has received financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities through research grant CSO2017-83086-R. We are grateful to Kathrin Ackermann, the editors and anonymous reviewers of the European Political Science Review, and participants at the 2018 European Political Science Association Annual Conference for helpful comments and suggestions.