Introduction

The institutionalization of power-sharing is a widely propagated measure to reach two inter-connected goals: stability and democracy. Although there is a large literature on power-sharing and peace, less systematic attention has been paid to its relationship with democracy. Given its accelerating global spread (Wimmer, Reference Wimmer2015) and use as institutional template by mediators (McCulloch and McEvoy, Reference McCulloch and McEvoy2018), this is a critical gap. In this article, we address this gap by discussing and empirically investigating how power-sharing entails trade-offs between several key aspects of the quality of democracy.

Previous contributions indicate that power-sharing supports the initial establishment of at least minimal democratic regimes (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1977; Linder and Bächtiger, Reference Linder and Bächtiger2005; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Miller and Strøm2017; Hartzell and Hoddie, Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2020). Yet, the resulting quality of democracy remains understudied. This is a crucial oversight, as both theoretical contributions and case studies highlight a number of critical shortcomings of power-sharing. These are, among others, the political exclusion of non-dominant social groups (Byrne and McCulloch, Reference Byrne and McCulloch2018), limited competition (Lehmbruch, Reference Lehmbruch and Lehmbruch2003; Rothchild and Roeder, Reference Linder and Bächtiger2005; Jarstad, Reference Jarstad, Jarstad and Sisk2008), and infringements on individual rights (Dixon, Reference Dixon2012; Stojanović, Reference Stojanović2018). Despite the prominence of this critique, quantitative studies have so far not sufficiently capitalized from the arguments in this literature, except for a large-N analysis of the impact of territorial self-government (Charron, Reference Charron2009).

Building on this literature, this article innovates on two grounds: first, it moves from the investigation of isolated consequences of power-sharing, such as unbalanced gender representation or reform blockages, to a comprehensive study of the quality of democracy in a broad range of aspects. This includes, in particular, those functions of democracy that are addressed by vocal critiques of power-sharing, such as participation, representation, liberal rights or inequalities in the public sphere. Second, earlier studies have primarily looked at democratic deficits in individual countries (e.g. Jung and Shapiro, Reference Jung and Shapiro1995; Bieber and Keil, Reference Bieber and Keil2009). Expanding on this, we assess the generalizability of their findings for 70 democracies during the period between 1990 and 2016 based on ‘objective’ indicators constructed from official statistics or representative surveys (Bühlmann et al., Reference Bühlmann, Merkel, Müller and Wessels2012).

In a first part of this article, we discuss how the characteristics of power-sharing jointly affect the quality of democracy. Most importantly, we expect power-sharing to be associated with a higher representation of the main ethnic segments, extensive group rights, and incisive horizontal checks and balances under control of political elites. In contrast, it deemphasizes the balanced representation of non-ethnically defined socio-economic groups, including gender, partly conflicts with individual rights, limits competition, and might entail a passive public and a non-transparent political process. Further, it is characterized by limited checks and balances outside of segmental control and is more likely to suffer from reform blockages that might limit government capability. In a second part, this article offers the first systematic, cross-national assessment of these expectations based on ‘objective’ measures. It does so by combining fine-grained data on the quality of democracy with a recent dataset on constitutional power-sharing.

Our findings offer a more optimistic picture than previous research. We find that power-sharing is associated with clear advances for several aspects of democratic quality, including the representation of diverse socio-economic groups, formal liberal rights, and political checks and balances. In contrast, in our sample, the shortcomings that country experts have identified in power-sharing democracies are not systematically different from those in majoritarian democracies. Partial exceptions are a somewhat more passive public and limited external instances of control.

We proceed as follows: A first section revisits the established wisdom in the emerging literature on power-sharing and democracy. A second one extends it by offering a comprehensive theoretical discussion of the features of power-sharing that intersect with the Quality of Democracy. We then conduct our systematic empirical analysis. Finally, we conclude.

Literature review

Building on Arend Lijphart’s seminal work on consociationalism, we conceive of power-sharing as a set of inclusive institutions which help establish and support democracy in plural societies (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1977). We focus on Lijphart’s three inclusive pillars, addressed as its ‘horizontal dimension’: grand coalition, proportional representation, and mutual veto rights. We exclusively consider formally institutionalized measures within these pillars, for example minority quotas. In contrast, we exclude three aspects. First, we do not consider inclusive institutions which do not follow the consociational logic, such as centripetalism. Second, we do not consider power-sharing behavior that lacks institutional undergirding, such as the ad hoc inclusion of ethnic minorities. Finally, we exclude Lijphart’s fourth pillar, segmental autonomy from our discussion (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1977). All these aspects influence democracy at the national level as well (Linder and Bächtiger, Reference Linder and Bächtiger2005; Bormann, Reference Bormann2014; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Miller and Strøm2017). However, they do not directly relate to the critique of power-sharing whose generalizability we seek to assess.

The relationship of power-sharing with democracy has received some previous attention. A prominent research strand argues that it may be the only option to establish and support democracy in ethnically heterogeneous places (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1977: 30). In such contexts, power-sharing helps overcome deep divisions by encouraging the formation of elite cartel-like governments and supporting compromises (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1968: 184). This restricted competition is ‘far from the abstract ideal’ (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1977: 8) and may resemble minimal democracy (Hartzell and Hoddie, Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2020), characterized by limited opposition (Barry, Reference Barry1975; Jung and Shapiro, Reference Jung and Shapiro1995). Recent research has highlighted further democratic deficits of power-sharing. Several scholars hold that power-sharing enshrines illiberal principles of group membership and deepens societal cleavages (McCulloch, Reference McCulloch2014). This sprawling literature has been primarily theory or case-study driven (Rothchild and Roeder, Reference Rothchild, Roeder, Roeder and Rothchild2005; Dixon, Reference Dixon2012). Thereby, it convincingly highlights shortcomings for specific cases, but has not yet assessed their generalizability. In addition, most empirical applications focus on individual aspects of democratic quality (Jung and Shapiro, Reference Jung and Shapiro1995; Joseph, Reference Joseph2011).

Conversely, the relationship of power-sharing with the quality of democracy has received far less systematic attention. A number of studies find that power-sharing supports transitions toward democracy (Bormann, Reference Bormann2014; Hartzell and Hoddie, Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2020), although the specific effects of its horizontal dimension are more controversial (Linder and Bächtiger, Reference Linder and Bächtiger2005; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Miller and Strøm2017; Juon and Bochsler, forthcoming). Other studies find that institutions linked to power-sharing are associated with higher overall levels of democracy (Hartzell and Hoddie, Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2020; Norris, Reference Norris2008). They employ aggregate scores of democracy as their dependent variable.

Yet, there is a substantial difference between assessing the level of democracy or its quality. Real-existing democracies differ in how they fulfill different functions of democracy (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1999; Lauth, Reference Lauth2016). This mirrors the understanding that ‘democracy is about more than elections’ (Morlino, Reference Morlino2004; Munck, Reference Munck2016: 1). It applies to countries that fulfill minimal, electoral criteria to qualify as democracies. In this vein, most theoretical or case-based critiques of power-sharing question the quality of democracy, and not the overall democratic nature of power-sharing. Switching focus to the quality of democracy enables us to account for its multiple underlying dimensions and the inherent trade-offs between them (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1999; Bochsler and Kriesi, Reference Bochsler, Kriesi, Kriesi, Lavenex, Esser, Matthes, Bühlmann and Bochsler2013). Empirically, this also allows us to go beyond aggregate, unidimensional measures employed in previous research, which might mask such important trade-offs.

There is a large literature that investigates the implications of consensus democratic systems, or its most prominent components, proportional (PR) electoral systems and federalism, for the quality of democracy (e.g. Armingeon, Reference Armingeon2002; Charron, Reference Charron2009; Kittilson and Schwindt-Bayer, Reference Kittilson and Schwindt-Bayer2010; Bernauer and Vatter, Reference Bernauer and Vatter2012; Doorenspleet and Pellikaan, Reference Doorenspleet and Pellikaan2013; Giuliani, Reference Giuliani2016). Consensus democracies have been described as being ‘kindler and gentler’ due to their positive associations with several aspects of democratic quality (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1999: 275–300; cf. Bernauer et al., Reference Bernauer, Bühlmann, Vatter and Germann2016).

However, power-sharing democracies are conceptually different from the consensus democracies. With proportional representation, they share a common component. Yet, power-sharing combines PR with more incisive rules which provide for inclusive executives and veto rights for the various ethnic segments (cf. Bogaards, Reference Bogaards2000).Footnote 1 In addition, the consensus democracy type is derived from the political practices that result from multi-party systems (cf. Bernauer et al., Reference Bernauer, Bühlmann, Vatter and Germann2016: 485). Conversely, power-sharing is conceptually much more specific (Andeweg, Reference Andeweg2000). Different from consensus democracies, its institutional restrictions circumscribe democracy much more strictly, with important ramifications for how it affects the quality of democracy (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1989: 41).Footnote 2 For instance, coalition bargaining in consensus democracies still renders elites accountable to electoral processes. In contrast, in power-sharing systems, prospects for elite alternation and accountability are often severely limited, for instance through strict executive quotas (Jung and Shapiro, Reference Jung and Shapiro1995). Hence, the findings from the literature on consensus democracy are unlikely to travel to power-sharing systems.

Overall, an incipient literature discusses how power-sharing institutions affect specific aspects of democracy. Yet, we lack a comprehensive theoretical discussion of its implications for the quality of democracy. Systematic cross-national studies, preoccupied with levels of democracy or with less incisive consensus democratic institutions, do not currently offer much guidance on the relationship between power-sharing and the quality of democracy.

Power-sharing and the quality of democracy

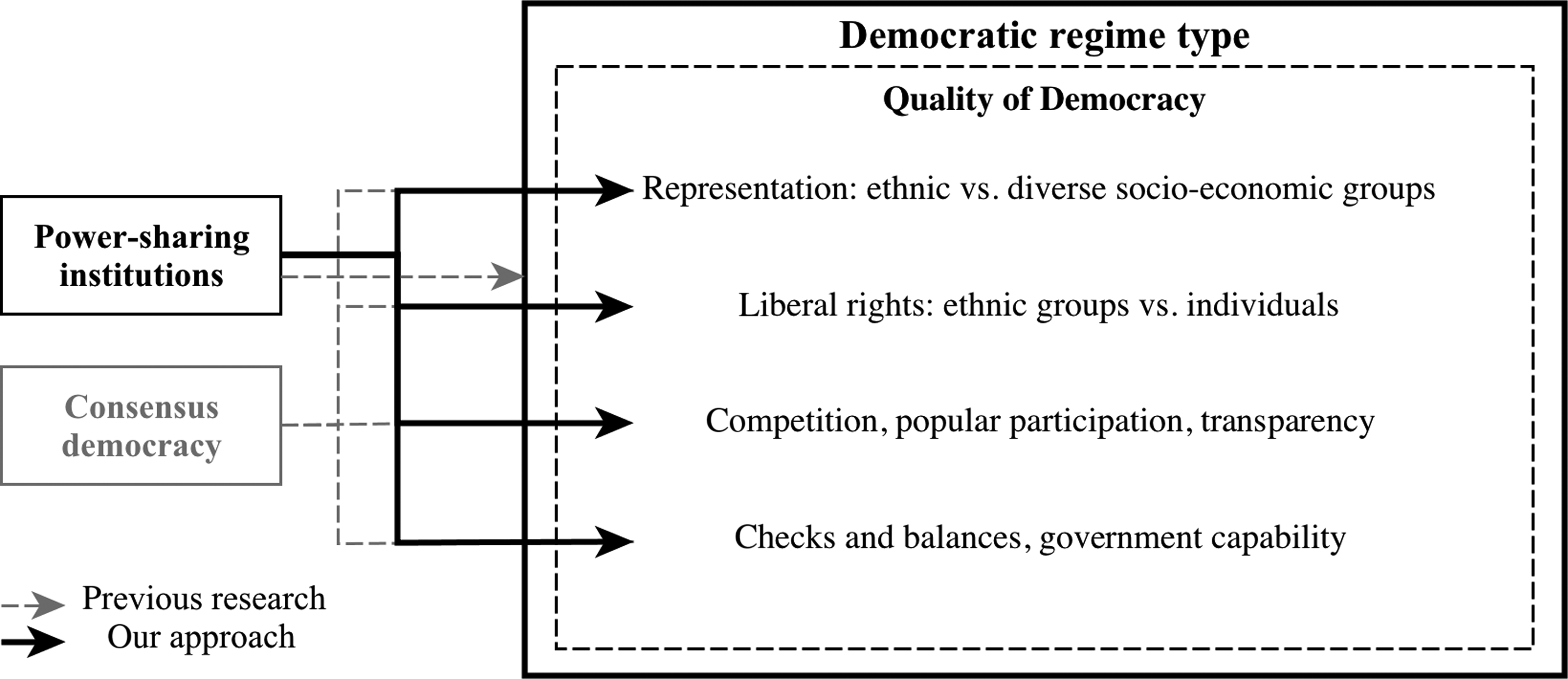

In the rest of this article, we take a further step toward a more integrated understanding of how power-sharing affects the quality of democracy. We start by intersecting two literatures, namely the critical assessment of power-sharing discussed above and the literature on the quality of democracy. We focus on four relationships between power-sharing and the quality of democracy. We argue that power-sharing advances some of its aspects, while deemphasizing others (see Figure 1 for a graphical overview).

Figure 1. Empirical approach.

The quality of democracy addresses the degree to which democracies fulfill key democratic principles. Beyond the minimal requirement of a democracy, reduced to its electoral function, it encompasses further principles. These include freedom, political equality (Morlino, Reference Morlino2004), effective control of elected power (Lauth, Reference Lauth2016), the quality of political representation (Roberts, Reference Roberts2009), and the capacity of the government to implement its decisions (Bühlmann et al., Reference Bühlmann, Merkel, Müller and Wessels2012). Other authors add to this the quality of political outcomes, such as economic and social equality (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1999).

All democracies meet these ideals only partially, as these are subject to inevitable trade-offs (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1999; Bochsler and Kriesi, Reference Bochsler, Kriesi, Kriesi, Lavenex, Esser, Matthes, Bühlmann and Bochsler2013; Lauth, Reference Lauth2016). We relate the critique of power-sharing to some of the most important of these trade-offs. Although some frameworks of the quality of democracy are too parsimonious in their dimensions to capture the nuances of the critiques of power-sharing,Footnote 3 we rely on a more extensive concept, covering democratic procedures and the social environment of politics (Munck, Reference Munck2016). This consists of a set of functions based on the democratic principles of freedom, control, and equality. This is close to the established frameworks of Diamond and Morlino (Reference Diamond and Morlino2004) and Bühlmann and colleagues (Reference Bühlmann, Merkel, Müller and Wessels2012).

In the following sub-sections, we discuss how power-sharing affects four key aspects of the quality of democracy. The first relates to the quality of representation and decision-making: elections need to be inclusive (based on universal suffrage and inclusive representation), competitive, make the government responsive to citizen preferences, guarantee broad participation, and result in effective political decision-making. The second addresses liberal rights and freedoms. Although some authors conceive of these as the defining properties of democracy (Merkel, Reference Merkel2004), their implementation arguably varies across full democracies (Beetham, Reference Beetham2004). The third relates to intermediaries between the state and the broader society. In particular, we conceive of the state as linked to society through civil organizations, the public sphere, and the transparency of government (Diamond, Reference Diamond1999: 218–60). Finally, the fourth relates to checks and balances that limit the power of elected governments. We now discuss these aspects in turn.

Representation and decision-making: main ethnic segments vs. other non-dominant groups

A first systematic relationship of power-sharing with democratic quality is a trade-off within the institutions of representation and decision-making. We argue that power-sharing provides for more inclusive representation of the main ethnic segments. Conversely, it deemphasizes the representation of non-dominant groups that do not identify with the main ethno-national divide, such as women, micro-minorities, and lower economic classes.

This trade-off derives from the emphasis of power-sharing on the political representation of the main ethnic segments. Most prominently, this comes in the form of government quotas for ethnic minorities, electoral districts gerrymandered to represent them, or group-specific veto rights (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1977). Together, these de-jure institutions boost the de-facto descriptive and substantive representation of the main ethnic segments that are targeted by them.

However, by privileging ethnic inclusiveness, power-sharing deemphasizes the balanced representation of other non-dominant groups, along with the issues facing them (Stojanović, Reference Stojanović2018). By reinforcing a narrow set of ethnic identifications, power-sharing might preclude alternative, cross-cutting modes of political participation. Most visibly, it may relegate the representation and concerns of women to a ‘secondary’ place behind ‘more urgent’ matters facing the main ethnic segments (Hayes and McAllister, Reference Hayes and McAllister2013: 34; Byrne and McCulloch, Reference Byrne and McCulloch2018). A similar marginalization should also characterize other non-dominant societal groups that do not map onto the main ethnic divide and are therefore not subject to the power-sharing agreement. These include micro-minorities and class-based groups (Stojanović, Reference Stojanović2018; Juon, Reference Juon2020).

A famous example for these tendencies is the three-headed presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It consists of a representative for each of the three constitutionally recognized ‘constituent peoples,’ the ethnic Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats, thereby limiting other citizens’ representation (McCrudden and O’Leary, Reference McCrudden and O’Leary2013). Its institutionalized representation along ethnic lines also deemphasizes socio-economic inequalities that cross-cut ethno-national divisions, such as class or gender (Byrne and McCulloch, Reference Byrne and McCulloch2018).

We translate this critique into two hypotheses, which can be assessed for a large number of countries:

Hypothesis 1: Power-sharing is associated with an increased representation of the main ethnic segments.

Hypothesis 2: Power-sharing is associated with a less diverse representation of non-ethnically defined non-dominant groups (e.g. socio-economic or gender groups).

Liberal rights: Groups vs. individuals

A similar trade-off applies to a second aspect of the quality of democracy, the liberal rights and freedoms of citizens. We expect power-sharing to boost the political, cultural, and economic rights of ethnic groups, especially those that make up the power-sharing system. Conversely, it deemphasizes and partly infringes on individual rights, especially those that transcend group boundaries.

Our reasoning again follows from the emphasis of power-sharing on ethnic groups. Along with boosting their representation, power-sharing constitutions protect the liberal and political rights of the groups that are recognized in the power-sharing agreement. These comprise cultural rights that are directly related to their identities, such as religious and linguistic freedoms. They also include further political rights, such as the freedoms of speech, association and assembly, and the right to organize in political parties. Although not explicitly aimed at ethnic groups, these rights are essential for their political participation and are hence typically boosted by power-sharing. Beyond the initial constitutional enshrinement of these rights, the political inclusion of minority representatives should empower them to enhance these rights even further over time (Hänni, Reference Hänni2017).

However, the tendency of power-sharing to increase liberal rights comes with a crucial limitation. Wherever group rights are in (partial) tension with individual rights, the rationale of power-sharing might require restrictions on the latter (McCrudden and O’Leary, Reference McCrudden and O’Leary2013). This is the case, for instance, when the free individual choice of identities risks undermining the demographic stability and political unity of ethnic groups. To counter such tendencies, power-sharing institutions might limit, inter alia, the right to choose one’s language of instruction or the right to self-identify when applying for public employment (Dixon, Reference Dixon2012; Stojanović, Reference Stojanović2018).

Two examples illustrate this dual relationship of power-sharing with liberal rights. The first is Macedonia’s comprehensive linguistic and cultural rights for ethnic Albanians. They were introduced in 2001 to strengthen its power-sharing constitution and subsequently expanded through coalition agreements between majority and minority parties (Brunnbauer, Reference Brunnbauer2002; Marusic, Reference Marusic2017). The second is South Tyrol’s regional power-sharing system, which provides comprehensive rights to ethnic Germans, Italians, and Ladins. However, it requires individuals to identify with one of these segments to access political functions and public services, thereby limiting individually based liberal rights (Stojanović, Reference Stojanović2018).

We formulate these considerations into a second set of testable hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3: Power-sharing is associated with a high institutionalization of rights and freedoms for ethnic groups.

Hypothesis 4: Power-sharing is associated with a low institutionalization of individual rights and freedoms that might erode ethnic group boundaries.

Popular participation vs. elite cartels

A third systematic relationship of power-sharing with the quality of democracy is related to control of the elites by the masses. Power-sharing relies on a model of group representation, whereby its institutions encourage the representation of each segment by its respective elites in a cartel-like government. To govern effectively, these elites require a large degree of autonomy (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1968; cf. Bogaards, Reference Bogaards2000). By concentrating power in this way, we expect power-sharing to have substantial drawbacks for several aspects of democratic quality: it should reduce democratic competition, public participation, and the transparency of the political process.

Government by elite cartel has the most direct implications for the institutions of representation and decision-making. Specifically, the mandatory government inclusion of all groups’ representatives may preclude the emergence of an effective opposition and stifle electoral competition (Jung and Shapiro, Reference Jung and Shapiro1995; Jarstad, Reference Jarstad, Jarstad and Sisk2008).

In the public sphere, the elite cartels encouraged by power-sharing institutions should further be associated with strong segmental civil society organizations. These enable elites to establish and sustain links to their respective group. They also serve to support and implement their political decisions, similar to corporatist state structures (Lehmbruch, Reference Lehmbruch and Lehmbruch2003).

Vice versa, direct channels of public participation are heavily discouraged. This in particular applies to alternative forms of participation that would allow citizens to bypass their elected elites and to exert influence beyond the formal electoral process. This might render the mass public ‘passive and apolitical almost everywhere’ (cf. Daalder, Reference Daalder1974; Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1977: 50; Dixon, Reference Dixon2012).

By encouraging elite cartels, power-sharing might also be detrimental for the transparency of the political process. By design, it often comes with limitations on transparent decision-making. These are required to safeguard the elites’ ability to engage in logrolling and to facilitate often unpopular compromises (Daalder, Reference Daalder1974). These tendencies are bolstered by the segmented civil society which encourages the formation of non-transparent patron-client relationships. Thereby, elites channel economic and political goods to their constituencies (Hale, Reference Hale2008), for example through partisan or otherwise identity-based appointments into the administration (Haass and Ottmann, Reference Haass and Ottmann2017).

Three examples illustrate this adverse relationship of power-sharing with competition, the public sphere, and transparency. A very prominent case is Lebanon, characterized by low competition for government positions that are distributed according to segmental criteria. Offices and policies are subject to logrolling between its segmental parties whose patronage practices enable them to ‘buy off’ supporters in their segments (Ghosn and Khoury, Reference Ghosn and Khoury2011). A similar characterization applies to Macedonia, where electoral participation is high, but characterized by a low confidence in the political system. At the same time, the ‘development of a civil society is rudimentary at best,’ with organizations ‘stamped by ethnic segregation’ and the newspapers divided along similar lines (Willemsen, Reference Willemsen2006: 87–88). Perhaps a less likely case is Belgium, where power-sharing is implemented through linguistically based parties. These ‘are primarily concerned about maintaining their own collective control,’ thus demobilizing their mass memberships (Peters, Reference Peters2006: 1081). While not exhibiting similar corruption as Lebanon, Belgium’s ‘partitocracy’ has also relied on patronage and clientelism. For instance, compared to other Western European countries, it disproportionately deemphasizes meritocratic criteria in favor of political ones to fill administrative and judicial positions (Ibid., cf. Popelier and De Jaegere, Reference Popelier and De Jaegere2016).

These considerations lead us to formulate a third set of hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5. Power-sharing is associated with decreased competition over political offices.

Hypothesis 6. Power-sharing is associated with low public participation outside of the formal electoral process.

Hypothesis 7. Power-sharing is associated with lower transparency of the political process.

Horizontal checks and state capability: Partisan vs. external veto points

A fourth systematic relationship of power-sharing with democratic quality derives from the type of veto points it enshrines. Power-sharing enshrines strong horizontal checks and balances that are under the control of the governing political parties. Conversely, it deemphasizes external instances of control that remain outside their influence. Although partisan veto points are conducive to compromises in decision-making, they risk producing reform blockages and thereby reducing state capability.

Multiple veto points in the political system, such as ethnic veto rights, supermajority rules, bicameral legislatures, or segmental autonomy serve as an important assurance for segmental elites so that their positions are reflected in political compromises (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1977; Norris, Reference Norris2008). However, we cannot assume a uniformly positive relationship of power-sharing with checks and balances overall. In particular, it should deemphasize institutional checks that award influence to actors outside of the power-sharing coalition, such as the judiciary or central bank. The goal of such external instances of control is to depoliticize certain issues. In the context of power-sharing, however, this would risk limiting the extensive autonomy of elites to reach mutually acceptable compromises (Diamond and Morlino, Reference Diamond and Morlino2004: 28). Hence, power-sharing should increase the former, partisan type of checks and balances, whereas deemphasizing the latter, external instances of control (Graziadei, Reference Graziadei2016: 84).

Partisan veto points have manyfold consequences. Adopted as part of power-sharing, they are intended to create incentives for compromises. However, power-sharing governments frequently include elites with diametrically opposed views or who are constrained by their polarized segments (Jung and Shapiro, Reference Jung and Shapiro1995; Rothchild and Roeder, Reference Rothchild, Roeder, Roeder and Rothchild2005). In this context, partisan veto points may negatively influence a key aspect in our first layer of democratic quality: the capability of government. Hence, the endowment of polarized elite actors with institutionalized powers to block decisions may impair government capability. Specifically, it may result in frequent, potentially severe, institutional deadlocks or reform blockages (Rothchild and Roeder, Reference Rothchild, Roeder, Roeder and Rothchild2005; Bieber and Keil, Reference Bieber and Keil2009).

Two examples illustrate these arguments. A first is Switzerland, where extensive checks and balances contrast with the limited prerogatives of the federal court. In 1848, these were circumscribed with the express purpose of upholding segmental autonomy. In addition, Switzerland’s judiciary is comparably dependent on executive or legislative power in its appointment procedures, putting it under partial control of the political elites (Seferovic, Reference Seferovic2010: 225–6; Edenharter, Reference Edenharter2018: 401–2). A second example is Belgium. Although its Constitutional Court enforces fundamental human rights, and thereby limits legislative acts,Footnote 4 it generally restrains itself from setting limits on political agreements related to segmental questions. Thus, the Belgian judiciary de-facto recognizes a particularly high legitimacy of power-sharing agreements (Popelier and De Jaegere, Reference Popelier and De Jaegere2016: 208). Although their strong political checks and balances have not resulted in severe institutional deadlock in either case, they slowed down the pace of political reforms in both countries. In Belgium, the coupling of partisan veto points with increasing fragmentation and decentralization have raised the risks of deadlock, most recently resulting in a 541 day long political crisis in 2010–11 where no government could be formed (Van Wynsberghe, Reference Van Wynsberghe, López-Basaguren and Escajedo San-Epifanio2019).

We formulate these considerations in a fourth set of hypotheses:

Hypothesis 8. Power-sharing is associated with a high institutionalization of checks and balances under the control of political actors.

Hypothesis 9. Power-sharing is associated with a low institutionalization of checks and balances outside the control of political actors.

Hypothesis 10. Power-sharing is associated with a lower government capability and effectiveness.

Empirical analysis

We now empirically assess evidence for and against these hypotheses. We start by presenting our data and modeling strategy before discussing our results.

Data

Different from earlier research on the relationship between power-sharing and democracy, our hypotheses necessitate measures that account for the multidimensional nature of democratic quality. Hence, we rely on disaggregated indicator measures from the Democracy Barometer (DB, cf. Merkel et al., Reference Merkel, Bochsler, Bousbah, Bühlmann, Giebler, Hänni, Heyne, Juon, Müller, Ruth and Wessels2018). Mirroring our approach, the DB embraces a middle-range concept of democracy, which conceives of democracy as based on individual freedom, equality, and actual control of the government over the state. Footnote 5 It comprises 105 indicators which directly relate to the aspects of the quality of democracy we discuss. These indicators are detailed enough to enable valid tests for most critiques of the power-sharing model. They include indicators for representative institutions (mostly within the DB functions of representation, competition), liberal rights (in the DB functions of mutual constraints, rule of law, individual liberties, and transparency), state-society relations (in the participation and public sphere DB functions), and checks and balances and government capability (in the mutual constraints and government capability DB functions).Footnote 6 All DB indicators are based on systematic data, primarily from ‘objective’ sources, such as official statistics and representative surveys. This allows us to complement the critical assessment of country experts.

The DB includes 70 established democracies since 1990.Footnote 7 This sample of established democracies is ideal for our purpose, which requires us to study variation in the quality of democracy, rather than changes between regime types. It also comprises a sizeable number of power-sharing democracies, including Bosnia, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Kosovo, Macedonia, South Africa, and Switzerland. Its temporal coverage further enables us to study the period since the end of the Cold War, when power-sharing institutions accelerated their spread around the globe (Wimmer, Reference Wimmer2015).

To operationalize our independent variable, institutional power-sharing, we rely on the Constitutional Power-Sharing Dataset (CPSD, Juon, Reference Juon2020). Based on constitutions and electoral laws, the CPSD codes power-sharing provisions pertaining to each of the three components of horizontal power-sharing: Grand coalition provisions (including appointment vetoes, executive quotas, and supermajority appointment rules), proportional representation (ethnic quotas for the legislature and proportional electoral systems), and mutual veto (veto rights for group representatives and legislative supermajority rules). These indicators are aggregated into an overall measure for horizontal power-sharing. Footnote 8 Among several datasets on power-sharing (Strøm et al., Reference Strøm, Gates, Graham and Strand2015; Vogt et al., Reference Vogt, Bormann, Ruegger, Cederman, Hunziker and Girardin2015; Hartzell and Hoddie, Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2020), this source is most suitable for our purpose, because it covers both post-conflict and non-conflict cases and all country years in the DB data. In addition, it mirrors our concept by focusing on institutions rather than ad hoc practices. As our argument necessitates that power-sharing institutions be implemented, we have excluded Cyprus from the analysis, where formal rules have not been operational since 1964. Finally, its measurement is distinct from common operationalizations of consensus democracy.Footnote 9 Table 1 gives an overview on major power-sharing periods in our sample.

Table 1. Power-sharing periods in the sample (index > 0.45)

Modeling approach

To investigate the democratic quality in power-sharing countries, we employ a set of controlled regression analyses. As our hypotheses require a disaggregated analysis, we estimate our models for each DB indicator related to our hypotheses separately. Most of the variation of power-sharing in our sample is cross-sectional (see Table 1).Footnote 10 In addition, we are interested in the association of power-sharing with democratic quality once democracy has emerged (as opposed to making causal claims about its effects on democratization). Hence, we opt for a simple pooled model specification and abstain from using country-fixed effects or first-differenced dependent variables. Instead, we use a number of controls and report country-clustered standard errors.

Each of our models additionally includes a number of control variables chosen to minimize the potential for third-factor-induced correlations between power-sharing and the quality of democracy.Footnote 11 These include economic development (logged GDP per capita), petroleum exports, ethnic fractionalization, recent experience of conflict, region-fixed effects,Footnote 12 and a year-term to model time dependence. As smaller states tend to be associated both with power-sharing and with a higher quality of democracy, we also control for country size (logged population and area in square kilometers).Footnote 13

Results

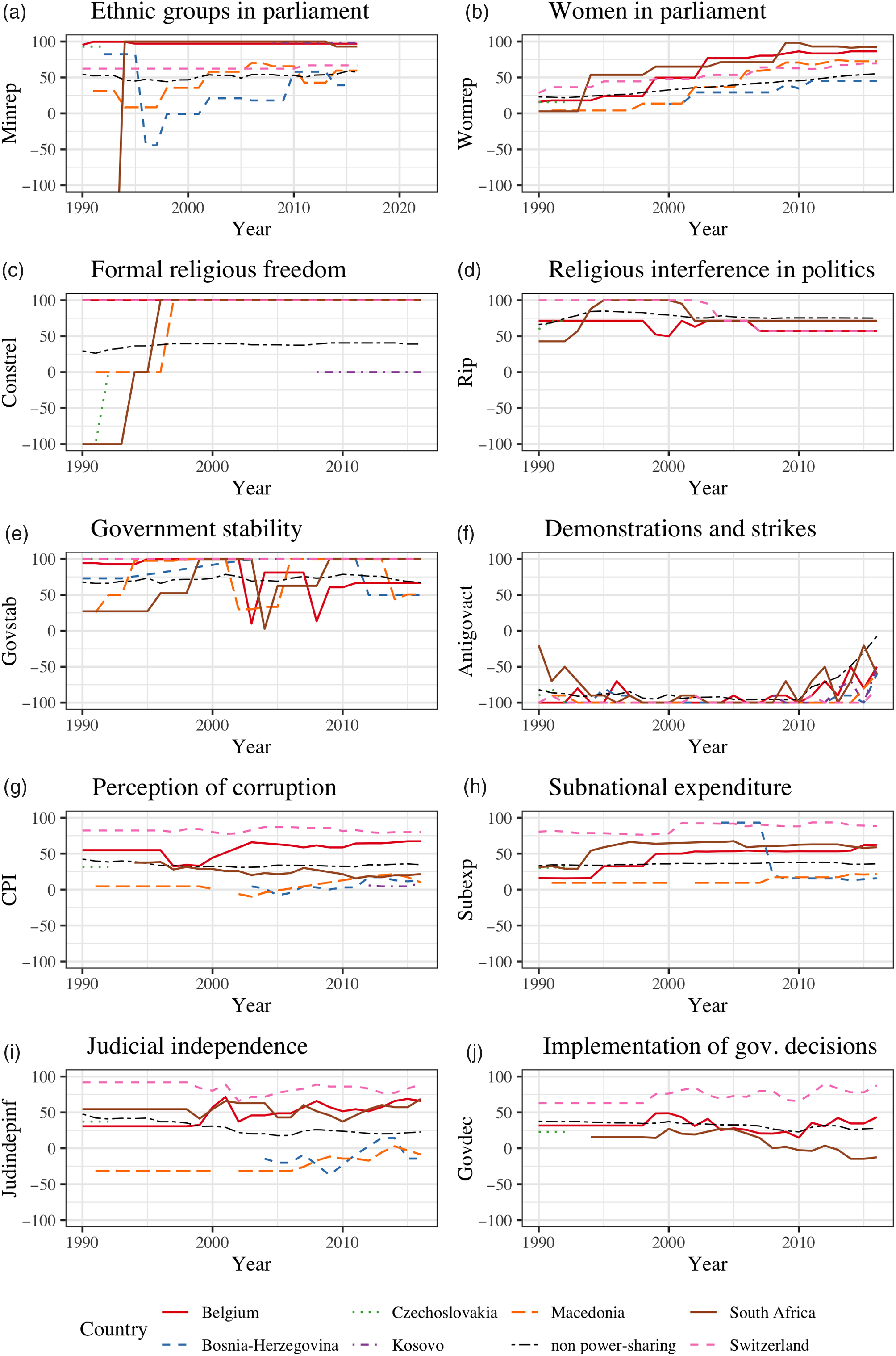

We now discuss the evidence for and against each hypothesis in turn. Table 2 displays a summary of our results. It shows the coefficient estimate and confidence level for our power-sharing measure in models covering all indicators that relate to our hypotheses, grouped by hypothesis number.Footnote 14 As we run a large number of models, we refer to Appendix 4.2 for full results, including control variables. In what follows, we illustrate our overall findings by assessing in more detail ten exemplary indicators in the power-sharing cases in our sample, comparing them to their respective average of all other countries (see Figure 2). Each of these exemplary indicators summarizes our attained evidence for or against our hypotheses.

Figure 2. Development of exemplary indicators in power-sharing and non-power-sharing cases. Minrep = minority representation in parliament; Womrep = women representation in parliament; Constrel = protection of religious freedom; Rip = religious interference; Govstab = government stability; Antigovact = demonstrations and strikes; Govdec = implementation of government decisions; Subexp = subnational expenditures; Judindepinf = judicial independence; CPI = perception of corruption.

Table 2. Results (coefficents for main variable, from model 1)

Note: *P < 0.1; **P < 0.05; ***P < 0.01; based on country-clustered standard errors. See Appendix 4.2 for full results, including control variables.

As regards the relationship of power-sharing with the representation of diverse groups, our results offer cautious reason for optimism. In line with Hypothesis 1, we find that power-sharing is associated with a vastly increased representation of ethnic groups in both parliament and the executive (although only the latter relationship is significant). Echoing this finding, Figure 2a shows that all power-sharing countries in our sample exhibit a higher government inclusion of ethnic minorities or, in the post-conflict cases of Bosnia and Macedonia, strong increases after their adoption of power-sharing in 1995 and 2001, respectively (cf. Bieber and Keil, Reference Bieber and Keil2009). The most striking development is the South African case, in which ethnic inclusiveness reached maximum levels when its new power-sharing constitution put an end to apartheid in 1992 (Jung and Shapiro, Reference Jung and Shapiro1995).

Conversely, we find no evidence for the expected drawbacks of power-sharing on the balanced representation of other socio-economic or gender groups (Hypothesis 2). Most strikingly, power-sharing is associated with an increased descriptive representation of women, both as regards their political rights and inclusion in parliament. Figure 2b shows that the power-sharing countries in our sample have a higher-than-average share of women in parliament. The only exception is Bosnia, which is just slightly below the average of non-power-sharing cases. These results are particularly remarkable, as earlier work has shown that women are less well represented when parties are organized along ethnic lines (Holmsten et al., Reference Holmsten, Moser and Slosar2010). This does not exclude the possibility that power-sharing diminishes the descriptive representation of women in some cases. Yet, these results point toward possibilities of engaging with power-sharing to increase gender balanced representation (cf. Byrne and McCulloch, Reference Byrne and McCulloch2018). However, our measures do not enable us to investigate whether the descriptive gender representation we capture also brings a substantive ‘gender perspective’ into politics (Bell and McNicholl, Reference Bell and McNicholl2019). Beyond this, we also find no evidence for arguments that power-sharing is associated with a less representative turnout or a lower ideological congruence between government and population. That would likely be the case if it systematically led to a less diverse representation of socio-economically defined groups.Footnote 15

We now turn to the relationship of power-sharing with liberal rights. In line with Hypothesis 3, we find that power-sharing is associated with increased formal liberal rights, even those that only are peripherally related to ethnic groups. These include bans against torture and the freedoms of religion, association, speech, and the press. Fitting illustrations of this relationship in our sample are the cases of South Africa and Macedonia (Figure 2c), both of which constitutionally enshrined the freedom of religion as part of wider power-sharing measures adopted in the 1990s and early 2000s, respectively (Jung and Shapiro, Reference Jung and Shapiro1995; Brunnbauer, Reference Brunnbauer2002; Marusic, Reference Marusic2017). However, in contrast to these formal rights, we attain no similarly positive effect for their implementation. This might reflect our measure of power-sharing, which is mainly based on constitutional guarantees, rather than political practice.

In further good news for the proponents of power-sharing, we find no evidence for its expected drawbacks on individual rights that might cross-cut ethnicity (Hypothesis 4). At least as given by our indicators for the freedom of movement and the political interference by religious bodies, we attain no systematic relationship. For the latter variable, all power-sharing countries are very close or only slightly below the average of non-power-sharing cases (Figure 2d). However, these indicators are somewhat suboptimal proxy variables. Hence, we cannot rule out negative relationships with individual rights that might erode group boundaries, such as the right for self-identification (cf. Stojanović, Reference Stojanović2018).

Next, we turn to our expectations related to the consequences of power-sharing by encouraging the formation of elite cartels. The literature criticizes power-sharing for thereby lowering competition (Hypothesis 5). Yet, we only find that, all else being equal, governments are less likely to change their composition over time. This draws a strong contrast to consensus democracies, as proportional representation and large party systems are associated with more cabinet changes (Taagepera and Sikk, Reference Taagepera and Sikk2010). In spite of this overall result, there were highly unstable periods in several power-sharing cases over time (Figure 2e). Yet, these seem less related to the cartelization of power and more to the polarization of the party system and difficulties of forming the coalition governments mandated by power-sharing (cf. Hypothesis 10). Macedonia experienced several cabinet reshuffles between 2002 and 2004, related to tensions between the inter-ethnic coalition partners (Willemsen, Reference Willemsen2006). Similarly, Belgium experienced a period of significant government instability during its 2007–11 political crisis, related to disagreements over the continuing unity of the state (Van Wynsberghe, Reference Van Wynsberghe, López-Basaguren and Escajedo San-Epifanio2019). Turning to our other variables, we also find that power-sharing is associated with a lower concentration of votes, a higher effective number of parties, and (insignificantly) more oversized governments. These reflect the inclusion of diverse political actors into the political system. There is otherwise no clear evidence for the cartelization of power, to the contrary: contemporary power-sharing democracies exhibit more rules to produce change in government than majoritarian democracies, such as shorter term limits or institutionalized election periods.

We now turn to our expectation that limited competition under power-sharing would lead to a passive public (Hypothesis 6). For this, our results are mixed. We attain negative associations of power-sharing with measures for informal public participation, such as lower propensities for demonstrations and strikes. This applies to all power-sharing cases, with the partial exception of South Africa (Figure 2f).Footnote 16 We also find an (insignificant) association of power-sharing with the percentage of registered voters. This is partly in line with the expectation that the cartelization of power reduces participation. However, we find no evidence that the public is less active in non-segmental civil society organizations, such as professional and environmental ones or trade unions. Altogether, this goes against blanket arguments that predict a general demobilizing effect of power-sharing.

We find partial evidence for the expectation that elite cartels encouraged by power-sharing entail a non-transparent political process (Hypothesis 7). Power-sharing is indeed negatively associated with several indicators that capture this concept well, including formal limits on party finances, autonomy of the bureaucracy, and perceptions of corruption. However, none of these correlations are significant. In addition, we attain no relationship of power-sharing with indicators related to the freedom of information. As Figure 2g suggests, these non-findings may be partly due to significant heterogeneity within the power-sharing cases in our sample. The more consolidated power-sharing democracies (Switzerland and Belgium) have a strongly decreased perception of corruption. Conversely, and reflecting our expectations, the opposite is the case for Macedonia, South Africa, Bosnia, and Kosovo. In addition, our non-findings may also arise due to overwhelming DB missing values for many of these indicators in several power-sharing democracies in our sample, including Bosnia, Macedonia, and Kosovo.

In a final step, we turn to the relationship of power-sharing with checks and balances and their consequences for government capability. In line with our expectations (Hypothesis 8), we find that power-sharing systems are positively associated with checks and balances that enable segmental elites to control one another, including federalism, bicameralism, and fiscal decentralization.Footnote 17

In contrast, institutional veto players that are outside of elite control indeed remain weak (Hypothesis 9). These include the judiciary, which has lower strength, is less impartial, and is perceived as more dependent on political actors. They also include the central bank, which has a lower degree of independence under power-sharing. This forms another remarkable contrast to the democratic type of consensus democracies, in which independent central banks form part of the model (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1999). However, these results are again subject to heterogeneity among power-sharing cases. As Figure 2i shows, for example, judicial independence exhibits striking deficiencies in Bosnia and Macedonia yet attains higher-than-average values for Switzerland, Belgium, and South Africa. In Macedonia, which consistently scores the lowest values, the direct accountability of the Constitutional Court to segmental political actors and the lack of an independent judiciary are key factors behind this result (Willemsen, Reference Willemsen2006). Overall, these findings are in line with our expectation that power-sharing should lead to more checks and balances under partisan control, but deemphasize external controls which cannot be captured by the governing coalition.

Finally, in spite of this partisan structure of veto points, we find no evidence that this in turn results in lower government capability (Hypothesis 10). First, contrary to our expectations, we attain no negative relationship of power-sharing with the efficient implementation of government decisions. Yet, although this indicator is related to our arguments, it may not adequately reflect deadlocks or reform blockages. These might result in the absence of decisions, rather than in failures of their subsequent implementation. Second, we also find a positive relationship of power-sharing with public confidence in the government. If institutional deadlocks were systematically more likely in power-sharing, we would expect the opposite relationship. However, similar to our transparency indicators, we again have systematic missing values of these indicators for the power-sharing cases in the Balkans (Figure 2j). Yet, in sum, the limited evidence we have points against our expectation that power-sharing would reduce government capability.

Robustness checks

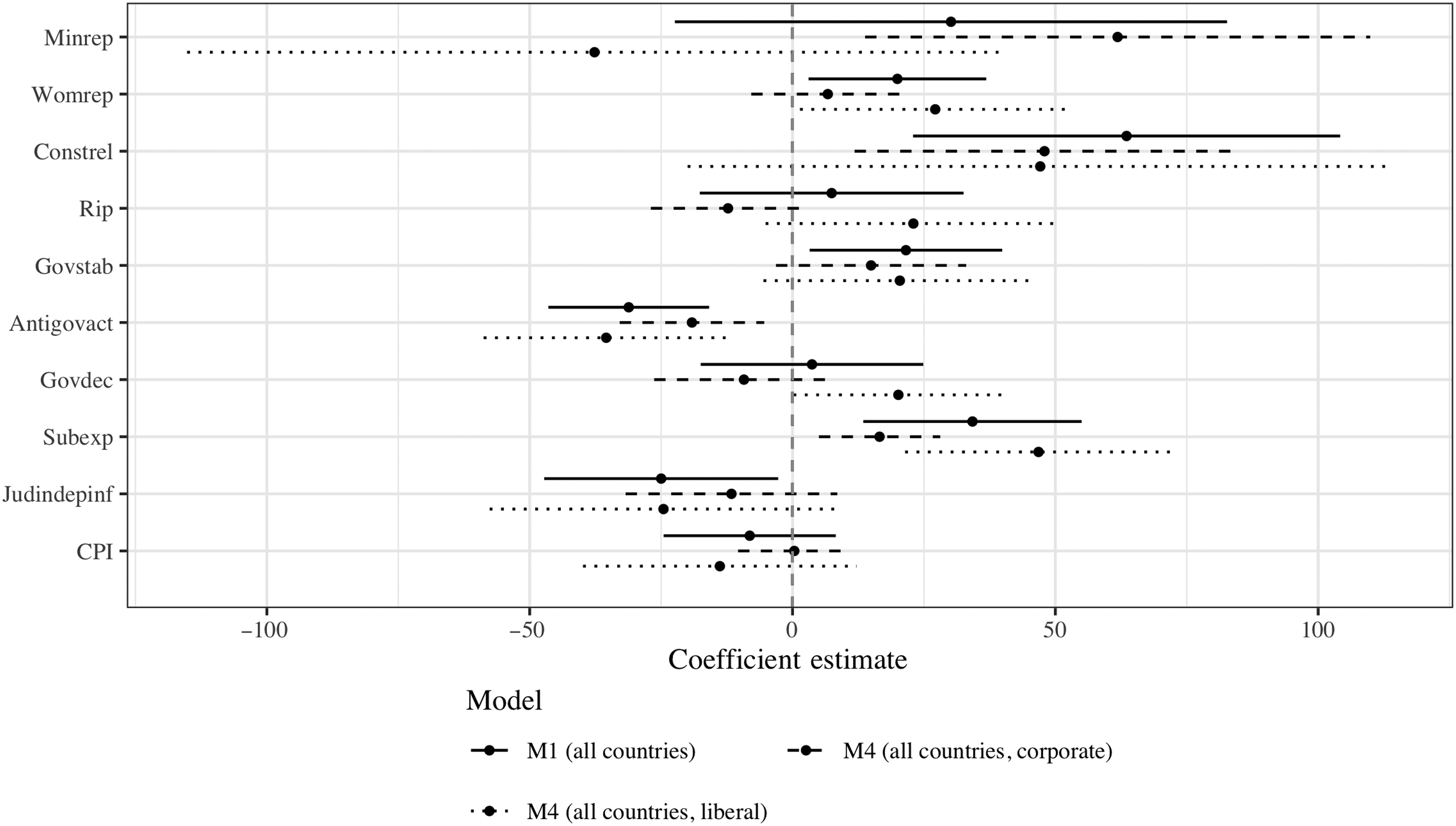

In addition to our main models, we also run a series of robustness checks to test our key assumptions. First, we have emphasized that the model of power-sharing democracy is distinct from consensus democracy, although both comprise PR electoral systems (Bogaards, Reference Bogaards2000, see Appendix 1.2). Hence, we re-estimated our models while controlling for the presence of PR electoral systems (robustness check 1) and while excluding them from our aggregated measures (robustness check 2).

Second, our set-up includes power-sharing democracies with dissimilar underlying institutions. However, corporate power-sharing might be disproportionately more likely to emphasize group rights at the expense of other aspects (McCulloch, Reference McCulloch2014; Stojanović, Reference Stojanović2018). Hence, we re-ran our models while differentiating between corporate and liberal power-sharing (robustness check 3).

Third, our study combines cases with diverging contexts that might influence both the adoption of power-sharing and subsequent democratic trajectories. To alleviate such concerns, we re-ran our analyses for two subsets: only ethnically heterogeneous countries (minority population greater than 5%, robustness check 4) and only post-conflict cases (robustness check 5).

In addition, we explore the sensitivity of our findings to three further aspects. In robustness check 6, we control for the age of democracy, as given by the Polity IV dataset (Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Gurr and Jaggers2019). This might affect both a country’s adoption of power-sharing and its baseline democratic quality. In robustness check 8, we replicate our findings with an alternative power-sharing measure, taken from Strøm and colleagues (Reference Strøm, Gates, Graham and Strand2015). Finally, in robustness check 9, we check whether our unexpected result on women’s representation is explained by gender quotas, often adopted simultaneously with power-sharing (Bell and McNicholl, Reference Bell and McNicholl2019).

Overall, our findings are remarkably robust. The main attained differences concern the representation of diverse groups under the two institutional sub-types of power-sharing. Figure 3 highlights this result for the same exemplary indicators used in the above discussion (see Appendix 3 for an expanded version of this figure that includes all other robustness checks). Corporate power-sharing is strongly associated with ethnic representation, although it has no systematic association with women’s representation. Conversely, the opposite applies to its liberal alternative. This result is closer to the critique of power-sharing we expected to find reflected in our sample. However, contrary to these arguments, even for the corporate type, the association with women’s representation does not become negative.

Figure 3. Coefficient plot: comparison across model types (exemplary indicators). See Figure 2 for indicator description.

Another limitation of our findings is the lack of temporal variation in our sample. Although we cannot address these concerns systematically, we provide a consolidated graphical overview of (North) Macedonia, which does see changes over time (Figure 4). Mirroring our main findings, Macedonia’s gradual increases in power-sharing agreed in the Ohrid peace talks of 2001 (Bieber and Keil, Reference Bieber and Keil2009) are associated with higher minority representation in parliament and a gradually increasing representation of women. Further, power-sharing appears associated with partial drawbacks, such as low-judicial independence and low demonstration and strike propensities (Willemsen, Reference Willemsen2006). However, these tendencies appear time persistent and largely unaffected by changes in formal power-sharing.

Figure 4. Evolution of exemplary indicators over time: Macedonia. See Figure 2 for indicator description.

Conclusion

Power-sharing is widely understood as the only type of democracy that is acceptable and sustainable in plural societies. In such contexts, it averts the permanent exclusion of ethnic minorities from political office. Yet, its practice in many plural societies has spurred concerns about its potential democratic shortcomings. These include limited competition, political immobilism, and infringements on individual rights (Jung and Shapiro, Reference Jung and Shapiro1995; Bieber and Keil, Reference Bieber and Keil2009; Dixon, Reference Dixon2012; McCulloch, Reference McCulloch2014). However, the generalizability of this prominent critique has so far not been assessed in a cross-national manner.

In our cross-national investigation, we find a robust association of power-sharing with several aspects of the quality of democracy. Most prominently, it provides for the better representation of diverse social groups compared to majoritarian democracies. Notably, this association goes beyond ethnic segments, which are particularly privileged by power-sharing. We find no evidence that power-sharing restricts the participation and representation of other groups. To the contrary, women – one of the ‘other’ groups not considered by power-sharing – tend to be better descriptively represented. We also find a strong association of power-sharing with formal liberal rights. In addition, we find that power-sharing comes with additional political checks and balances that enable segmental elites to control one another.

In our sample, we attain only two partial drawbacks: First, the public tends to be more passive in power-sharing democracies, at least as regards informal participation. However, this is not mirrored by lower public engagement in the civil society, thus contradicting arguments that power-sharing would demobilize the public across the board. Second, we find that power-sharing is associated with weaker external instances of control that remain outside the influence of segmental elites.

In light of the global importance of power-sharing as a constitutional template for plural societies, these findings are reassuring. Vocal critiques of power-sharing have highlighted its illiberal traits in recent applications of power-sharing, mirrored by cross-national expert assessments (see Appendix 5). However, our reassessment of this critique with ‘objective’ indicators indicates that these pitfalls may be more isolated than previously thought, and not altogether dissimilar from the shortcomings in majoritarian democracies. Our findings hence also highlight a considerable discrepancy between the perception of the quality of democracy in power-sharing systems by country experts and a set of largely ‘objective’ indicators.

Are power-sharing regimes thus ‘kinder and gentler’ democracies (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1989, Reference Lijphart1999)? Our results only provide partial support for this interpretation. Although positive associations prevail, they are confined to three aspects that appear very proximate to power-sharing: First, power-sharing is associated with more inclusive government institutions. However, with the exception of women’s representation, these relationships constitute immanent effects of power-sharing and can hardly count as strong evidence that these would spill over into other spheres of democracy. Second, power-sharing is associated with higher constitutional protections of liberal rights and freedoms. However, these are not equally consequential in de-facto practice, thus raising concerns that they might mostly represent token measures. Finally, (horizontal) power-sharing is positively associated with political checks, such as federalism, bicameralism, and fiscal decentralization. However, these institutions and practices are directly associated with power-sharing and hence also cannot count as far-ranging relationships (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1977; McCulloch, Reference McCulloch2014).

In sum, our empirical assessment highlights the democratic qualities of power-sharing, rather than its illiberal shortcomings. However, these qualities remain limited to the core domains where power-sharing has a direct effect, and do not go much beyond.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773921000151.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Michelle Roos for invaluable coding assistance. We thank Adis Merdzanovic, Benjamin McClelland, Guido Panzano, and Livia Rohrbach for helpful comments. We have received generous financial support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 166228) and the Centre for Democracy Studies Aarau (ZDA).