Introduction

Party competition and party system development is one of the most intriguing questions which have occupied party and electoral scholars’ minds. In the last couple of years of elections around the European continent, we have seen a number of unexpected changes within both the well-established democracies of Western Europe and the newer democracies from post-communist Europe. One of the latest, and perhaps largest, party system changes comes with the results we observed in the French presidential and parliamentary elections, where Emanuel Macron qualified for the presidential election run-off winning over all traditional political parties after establishing the En Marche! political movement a month before the election. Many post-communist European countries also have experienced dramatic party system change over time. For instance, new parties entered the Moldovan parliament in the 2019 election with quite a sizeable first-time support. In Slovenia, the largest party in the 2014 Slovenian parliamentary election (Modern Center Party, SMC) and that in the 2011 election (Positive Slovenia, PS) were new parties. New parties also had a strong appearance in Bulgaria. The parties that gained the largest share of votes in the 2009 and 2001 parliamentary elections, Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB) and the National Movement for Stability and Progress (NDSV), were new parties. In Latvia, new parties gained the largest electoral support in the 2002 (New Era Party), 1998 (People’s Party), and 1995 (Democratic Party ‘Saimnieks’) parliamentary elections.

Scholars have argued that party system size matters for political representation and accountability (Powell, Reference Powell2000). A trade-off between representation and accountability suggests that a larger party system facilitates representation for diverse interests, while a smaller party system produces a more accountable government (Carey and Hix, Reference Carey and Hix2011). The changes in party systems call the question of what explains party system size back to the table. Explored for many decades, explanations that a large part of the literature on party systems gives relate to electoral institutions (Duverger, Reference Duverger1954; Sartori, Reference Sartori1976; Blais and Carty, Reference Blais and Carty1991; Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1994; Benoit, Reference Benoit2001; Clark and Golder, Reference Clark and Golder2006), social cleavages (Ordeshook and Shvetsova, Reference Ordeshook and Shvetsova1994; Amorim Neto and Cox, Reference Amorim Neto and Cox1997; Rashkova, Reference Rashkova2014a), economic factors (Casal Bértoa and Weber, Reference Casal Bértoa and Weber2019), and political contexts (Mair, Reference Mair1997: 175–198; Rashkova, Reference Rashkova2014b; Enyedi and Casal Bértoa, Reference Enyedi and Casal Bértoa2018). Many of these studies posit that it is electoral rules, namely the district magnitude, and social diversity that determine the number of political parties in a given system. A more recent wave of research on party system development has shown, however, that in addition to electoral and social factors, rules such as signatures and pre-electoral deposits (Bischoff, Reference Bischoff2006; Tavits, Reference Tavits2008; Rashkova, Reference Rashkova2014b; Su, Reference Su2015) affect party system development. Covering European and Latin American democracies and testing the effect of electoral regulations beyond the district magnitude alone, most of these studies find that increasing the ‘barriers to entry’ by instituting a high electoral deposit or a high signature requirement has a negative effect on party system proliferation. Particularly, it has an adverse effect on new party entry, which can be argued, is bad for democracy.

A related debate on the extent and the manner in which party regulation encourages or constrains party system development has taken off quite rapidly in the last decade (van Biezen and Kopecký, Reference van Biezen and Kopecký2007; Casal Bértoa et al., Reference Casal Bértoa, Molenaar, Piccio and Rashkova2014; van Biezen and Rashkova, Reference van Biezen and Rashkova2014). These studies examine the ‘state intrusion’ in party politics and the extent to which party regulation affects party system development.Footnote 1 Stemming from the Katz and Mair’s (Reference Katz and Mair1995) seminal cartel party thesis article, almost all work on party regulation is guided by one overarching question – do (or do not) political parties in power create, alter, and let go of regulation in a way that helps them retain their position within the political space? van Biezen and Rashkova (Reference van Biezen and Rashkova2014) convincingly show that increased party regulation deters new entrants and thus provide evidence for the observation made earlier that elected political parties cooperate with each other in making new legislation to govern parties’ establishment, activities, and competition, regardless of their ideological distances (Katz and Mair, Reference Katz and Mair1995).Footnote 2 These and other similar suggestions beg the next question – ‘are all regulations (created) equal?’. Specifically, financial regulation of political parties has drawn significant media attention in the last number of years. Given the fact that there are ongoing cases of political corruption, financial scandals involving major political actors, and a tremendous rise in the regulation of political finances (Rashkova, forthcoming; van Biezen and Kopecký, Reference van Biezen, Kopecký, Scarrow, Webb and Poguntke2017), studying the relationship between this specific type of regulation – political finance regulation – and party system development presents a main point of interest. Building on recent work engaging with this issue (Booth and Robbins, Reference Booth and Robbins2010; Gauja, Reference Gauja2010; Potter and Tavits, Reference Potter and Tavits2015; van Biezen and Kopecký, Reference van Biezen, Kopecký, Scarrow, Webb and Poguntke2017; Casal Bértoa, Reference Casal Bértoa2017), we try to enrich the study of the relationship between party financing and party system development by focusing on comparing its effects on party systems in different contexts. Our theorizing of the different manners in which party finance affects party competition in new and established democracies complements in an innovative way the results shown by Potter and Tavits (Reference Potter and Tavits2015).

While scholars are busy disentangling the link between money and politics, as Scarrow (Reference Scarrow2007) puts it in her survey of political finance, we are ‘mounting evidence, [but] lagging [in] theory’ (Scarrow, Reference Scarrow2007: 206). Recognizing that there is no universally applicable recipe to the design of political finance arrangements, Scarrow (Reference Scarrow2007) suggests that there is nevertheless scope for more systematic efforts in understanding the origins and impact of different political finance rules. Building on extant work on the effect of party regulation and party competition and the concrete link between party funding and party system development, we examine the question of how political finance rules affect party competition within the context of 43 European democracies. In particular, we are interested to take a deeper look at political finance regulations and one that considers the side of a newcomer. In this respect, we use Potter and Tavits’ (Reference Potter and Tavits2015) theoretical concept of fund parity to operationalize political finance regimes. We innovate what has been done so far by demonstrating that rules with higher levels of fund parity enlarge party system size in new but not in established democracies.

The paper proceeds as follows: The next section discusses the concept of fund parity and situates our study within the scholarship that has examined the relationship between political finance and political competition. Third section describes our data and method, followed by a section with the empirical analysis. The final section summarizes our findings and concludes.

Fund parity and party system development in established and new democracies

The question of the relationship between money and politics is not new. Both money and politics have existed for as long as most systems governing today’s world have as well. Yet, only recently, with the rise of corruption scandals, both intergovernmental and governmental organizations, as well as scholars, have started paying closer attention to the link between money and politics. The former has responded to the ensuing legitimacy crises (van Biezen and Rashkova, Reference van Biezen and Rashkova2014) by instituting new rules – some introducing public funding, other regulating it, yet others, by constraining private funding and so on. The argument for the introduction of public funding, as Scarrow (Reference Scarrow2006) notes, has been justified in two ways – one, emphasizing the worthiness of political parties, the other their fallibility. In an attempt to ‘draw back the attention of the voter’ and re-build their legitimacy, political parties across the globe began to regulate parties’ finances and as many as 61% of world’s electoral democracies introduced public subsidies in order to curb the influence of private interests, via large amounts of money, in politics. In a recent Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) report on public funding in Northern, Western, and Southern Europe, Piccio (Reference Piccio, Falguera, Jones and Ohman2014: 237) states that as a result of these changes around the globe, public funding has become the major source of income for political parties in Western Europe, constituting almost three quarters of all party income in the region. Furthermore, a number of countries have introduced bans on corporate donations and instituted limits on contributions from individual persons. The former is especially true for the new democracies of Eastern Europe. According to McMenamin (Reference McMenamin2013), six out of the eight European democracies, which have adopted a ban on corporate donations, are democracies from Eastern Europe.

Regardless of its growing popularity, the question on how political finance regulation affects party competition is still without a definitive answer. Katz and Mair’s (Reference Katz and Mair1995, Reference Katz and Mair2009) seminal cartel party thesis suggests that existing parties might try to deter new party entrants by collusively making it difficult for parties to access public funding. Other studies also find that larger parties disproportionately benefit from laws (e.g. van Biezen and Rashkova, Reference van Biezen and Rashkova2014). In contrast, Casas-Zamora (Reference Casas-Zamora2005) argues for a ‘context-driven case-study approach’ as the superior way to advance our understanding of the role and impact of political finance and finds, opposite to widespread beliefs of the cartel party thesis, that public funding not only does not stifle party competition, but it actually helps new parties. Looking at the question from a different angle, Casal Bértoa and Spirova (Reference Casal Bértoa and Spirova2019) show that parties that are funded or anticipate to be funded by state subsidies tend to have a higher survival rate than non-publicly funded parties. In a survey of party subsidies around the world, Scarrow (Reference Scarrow2006) cannot find evidence that confirms or disconfirms the cartel argument one way or another, but her work illustrates the importance to look deeper at the design of political finance rules, as countries exhibit great variation on specific regulations such as the payout threshold, for example.

Contrary to previous studies (Tavits, Reference Tavits2006, Reference Tavits2008; Booth and Robbins, Reference Booth and Robbins2010; Rashkova, Reference Rashkova2014b), which largely consider whether a specific aspect is present or absent within the financial laws, we look at the content of the regulation and are thus better able to gauge the potential effect that a specific financial regulation may have on the party system. For example, if we simply consider whether public funding exists, and we take for granted the existence of public funding as stimulating for party competition and thus for newcomers, we are likely to come to the wrong conclusions. Using a sample from around the world, Potter and Tavits (Reference Potter and Tavits2015) systematically establish whether there is a link between political financial regulations and party system size. The authors operationalize the regulations in a ‘fund parity’ variable looking at whether the opportunities provided by the law are equal for small and larger parties. They hypothesize that when the campaign laws downplay the financial advantage that larger parties have, indicating that the electoral playing field has a higher level of fund parity, we will see more political parties, and thus larger party system size.

According to Potter and Tavits (Reference Potter and Tavits2015), the concept of fund parity consists of four types of financial regulations: (1) direct public funding; (2) indirect public funding (free or subsidized media access for parties); (3) campaign expenditure limits; and (4) private donation limits. For the first two regulations, the payout threshold is what actually determines what the potential effect of public funding will be (Scarrow, Reference Scarrow2006). Therefore, the legal scenario that is most favorable to small parties is that state subsidies are allocated equitably to all parties, while the scenario that is least favorable to small parties is that the eligibility requirements for state subsidization are based on previous electoral performance. In the latter, existing larger parties clearly have much more advantages over small or new parties. A country with no public funding regime will be less restrictive to party competition, than a country which offers public funding but it is based on electoral performance or parliamentary representation, for example. Similarly for indirect public funding – if such does not exist, the playing field can be considered to be more equal, than if such exists, but favors incumbents (as is often found with free media time allocation rules for campaign advertisements). The logic here is somewhat counterintuitive, yet the reasoning is that no funding for all provides a more equalized playing field for all parties – incumbents and newcomers – while existing public funding regimes that favors incumbents would undermine the electoral prospects of potential new entrants.

For the regulation of campaign expenditure and private donation, Potter and Tavits (Reference Potter and Tavits2015: 78) argue that they ‘can be understood as “power-curbing” provisions that tie the hands of larger parties and their influential donors’. When a party can spend its financial endowment as much as it can, ‘these funds can be used to crowd out any of the opponents’ messages;’ moreover, when there is no limit for private donations, a party can increase its financial endowment as much as it can and thus wealthy donors ‘are likely to channel their financial contributions to parties with governing potential’ (Potter and Tavits, Reference Potter and Tavits2015: 78). Therefore, no limits on campaign expenditure and campaign donation make larger parties more electorally advantageous. In contrast, when there are limits for the overall amount that a party can spend for campaigns and for the overall amount that a party can receive in private donations, larger parties are likely to reach the cap soon, and thus the content, instead of volume, of campaign messages becomes a crucial factor in the electoral competition (Potter and Tavits, Reference Potter and Tavits2015). In this scenario, small or new parties without sizeable financial endowments are able to compete with larger parties on a more equal footing. Taking together the above discussion suggests that an institutional environment with the highest level of fund parity is where both direct and indirect public funding are distributed equitably to all parties, and the finance laws set limits for both campaign expenditure and donations.

Following Potter and Tavits (Reference Potter and Tavits2015), we contend that fund parity is useful for understanding the impact of campaign finance laws on electoral competition. However, we move the discussion a bit further. In particular, we introduce a more elaborate theoretical reasoning encompassing the potential effect of political finance regulation. We hypothesize that financial regulation will have a different effect in established and new democracies. We argue that financial regulation adopts a design with higher levels of fund parity and are more likely to encourage more new parties to enter electoral competition in developing democracies than in established democracies. The reasoning behind this expectation is twofold. First, as Enyedi and Casal Bértoa (Reference Enyedi and Casal Bértoa2018: 423) indicate, the past experiences under communism, the weak mass political organizations, the unstable economic performance since the 1990s, and a political culture that largely centers on elites are important factors that might hinder party system institutionalization in post-communist European countries. Due to the fact that post-communist democracies are new and their party systems are less institutionalized and thus more fluid than those in established democracies, there is more ‘room’, as well as a higher incentive (due to potential high payoffs) for newcomers to attempt entry into the party system.

Second, given the overall lower financial ability of actors in newly democratized states, when these actors anticipate to have an equal chance to access campaign resources, they might have more incentives to form parties because their parties are more likely to sustain themselves continuously by receiving public funds upon establishment. Therefore, political finance regimes that promote fair play for competition would make a significant difference to political entrepreneurs who want to enter the party system in new democracies. In contrast, in established democracies, financial regulations with higher levels of fund parity might only have moderate if not negligible influence on party system size. First, assuming that a party’s electoral viability depends on its electoral histories (Cox, Reference Cox1997: 158), voters in established democracies have more experiences of strategic voting and thus they are less likely to support new parties that have no electoral histories (see also Tavits, Reference Tavits2008). Second, because political elites in established democracies are generally better-off economically, the financial cost for establishing a new party should not be a serious concern for them; therefore, whether the finance laws provide equitable conditions for new parties or not might not greatly affect these elites’ decisions to form a new party.

In short, Potter and Tavits’ (Reference Potter and Tavits2015) original argument for fund parity suggests that higher levels of fund parity encourage newcomers to enter the political space. However, we further argue that the effect of fund parity on party system size might depend on different political contexts. Here, we argue that the effect of fund parity on enlarging party system size matters more for new democracies than established ones. Given the fact that new democracies are generally also less developed economically, politicians in new democracies might have less resources to establish new parties and sustain the party survival. When there is no level playing field for new parties to compete, politicians might have even less incentives to establish new parties. Second, politicians in new democracies generally lack important skills and experiences to form new parties that are viable to contest elections. In other words, without sufficient democratic learning experiences, there exists a great uncertainty of obtaining electoral support, and thus an institutional environment that gives more financial advantages to larger parties makes political elites more reluctant to form new parties. Complementing the study of Potter and Tavits (Reference Potter and Tavits2015), we hypothesize that the effect of fund parity on enlarging party system size will be stronger in new democracies.

In fact, previous studies have tested the impact of party financing on party system size in different contexts. For instance, Tavits’ (Reference Tavits2006) analysis of 22 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries demonstrates that the availability of public funding does not have a statistically significant effect on the number of new parties. In contrast, Tavits’ (Reference Tavits2008) analysis of post-communist European democracies shows that the change from providing no public funding for parties to having some public funding significantly increases the expected count of new parties. Potter and Tavits’ (Reference Potter and Tavits2015: 83) empirical finding suggests that party system size tends to increase when party financing rules allow smaller parties to compete on a more equal footing with larger parties in both samples of all democracies and new democracies. Because these studies examine the impact of party financing using separate samples for established democracies and new democracies, it will be misleading to draw a conclusion from these studies about whether party financing matters more for one context than the other. In our paper, we make an empirical contribution to the literature by testing jointly the effect of political finance laws for different contexts. Given that fund parity is assumed to have a stronger effect on new democracies, we adopt the interaction variable approach to better capture to what extent the effect of fund parity is different on party system size across different democracies.

Data and model specification

The unit of analysis in our empirical analysis is country election.Footnote 3 We measure our outcome variable – the effective number of parties in votes (ENPV) – using the standard formula developed by Laakso and Taagepera (Reference Laakso and Taagepera1979), which is the inverse of the sum of squares of each party’s vote share in an election. This variable was constructed using results of lower chamber elections in 43 European democracies,Footnote 4 and the data are mainly from Gallagher (Reference Gallagher2019).Footnote 5

To measure our main explanatory variable – fund parity – we rely on the Funding of Political Parties and Election Campaigns project of the International IDEA handbook series, including Austin and Tjernstrom (Reference Austin and Tjernstrom2003), Falguera et al. (Reference Falguera, Jones and Ohman2014), and International IDEA (2018). Therefore, the databases provide three periods of measurement about fund parity for the European countries included in our analyses. We follow Potter and Tavits (Reference Potter and Tavits2015) by focusing on four items in the International IDEA surveys that pertain to the nature of campaign finance in each country: (1) direct public funding eligibility; (2) free or subsidized media access eligibility; (3) limits on the amount of private donation; and (4) limits on the amount of party expenditure.Footnote 6 Following Potter and Tavits’ (Reference Potter and Tavits2015) coding scheme, we construct a metric of fund parity, which takes the values −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4. The first item is coded 1 if direct public funding is allocated equitably to every party, −1 if such funding is allocated based on their past performances (a required particular vote share or presence in the parliament), and 0 if there is no directed public funding provided for parties. The second item is coded 1 if free or subsidized media access is allocated equitably to every party, −1 if it is allocated based on their past performances, and 0 if there is no free or subsidized media access provided for parties. The third item is coded 1 if there is a limit on the amount of money an individual can donate to a party and 0 otherwise. The fourth item is coded 1 if there is a ceiling for the amount of money that a party can spend for campaigns and 0 otherwise. The metric of fund parity is coded by summing the coded value for each of the four items mentioned above.Footnote 7 A higher value of this additive metric indicates that the country provides more equal conditions for party competition.

We follow the data structure of Potter and Tavits’ (Reference Potter and Tavits2015) study for our analysis. Because there are three periods of measurement about fund parity, which are 2002–2003, 2011–2012, and 2017–2018, most countries in our dataset have three observations. In other words, the coding for fund parity for the first/second/third observations indicates the fund parity measured for 2002–2003/2011–2012/2017–2018. We use the following coding rules for our dependent variable. First, if a country held national legislative elections in 2002, 2003, 2011, 2012, 2017, or 2018, our dependent variable for the observations of that country was coded based on the results of the elections held in these years. In our dataset, there are no countries that held more than three elections in these six years. For a country that did not hold national legislative elections in 2002, 2003, 2011, and 2012, we used the result of the first election held after 2003 for coding the dependent variable for the first observation of the country and the result of the first election held after 2012 for the second observation of the country. Most countries in our dataset have two or three observations, except for Serbia (one observation) and Montenegro (one observation).Footnote 8

Our research design differs from Potter and Tavits’ (Reference Potter and Tavits2015) in three ways. First, while they only cover two periods for each country (2002–2003 and 2011–2012), we cover three periods with new data from IDEA International (2002–2003, 2011–2012, and 2017–2018). Second, we focus on studying European countries, and we do so because it allows us to control for unobserved heterogeneity that is specific to this region. Moreover, there is great variation in fund parity and party system size in Europe, and thus analyzing these countries facilitates our understanding of party politics in a comparative perspective. Third, we modify Potter and Tavits’ theory of fund parity by hypothesizing that the effect of fund parity on enlarging party system size is not direct, but conditional on the political contexts. Specifically, our hypothesis suggests that while a country with more equity-oriented funding rules for parties tends to have larger ENPV, the effect of such rules will be stronger for new democracies. To test this hypothesis, we include a dummy variable for New Democracy, operationalized as post-communist democratic country, and an interaction term New Democracy*Fund Parity. Both variables interact in enlarging party system size and so, according to our theoretical argument, we expect a positive association between the interaction term and the ENPV.

In our empirical models, we control for a battery of variables that could potentially influence party system size. First of all, we control for two other important variables about party formation: petition signature requirement for party registration and monetary deposit for registering parties/candidates for electoral campaigns (Hug, Reference Hug2001). Studies have shown that a monetary deposit for registering a new party deters the entry of new parties (Tavits, Reference Tavits2008), and a petition signature requirement also suppresses the number of parties (Su, Reference Su2015).

In addition, we include the logarithmic transformation of district magnitude to control for the possibility that a larger district magnitude might encourage multipartism. Previous research has shown that the number of parties is a function of the interaction of both district magnitude and the number of social cleavages (Ordeshook and Shvetsova, Reference Ordeshook and Shvetsova1994; Amorim Neto and Cox, Reference Amorim Neto and Cox1997). Thus, we include the average district magnitude weighted by district size (Cruz et al., Reference Cruz, Keefer and Scartascini2018), ethnic fractionalization (Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Devleeschauwer, Easterly, Kurlat and Wacziarg2003), and an interaction term of these two variables.

Moreover, GDP growth and the inflation rate are included as controls; these variables are lagged by 1 year to capture the short-term economic influence on elections. Furthermore, we include a variable about the experience of democracy. Studies have suggested that the number of new parties is expected to decrease over time as a democracy experiences more elections (Tavits, Reference Tavits2008: 117). Since we expect a diminishing effect over time, logarithmic transformation of the number of years since the beginning of the current democratic regime in a country is used for our analysis.Footnote 9 Descriptive statistics for all variables included in the analyses below are provided in the online Appendix.

Following recent studies that examine the effective number of parties (van Biezen and Rashkova, Reference van Biezen and Rashkova2014; Potter and Tavits, Reference Potter and Tavits2015; Su, Reference Su2015), we use ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions to analyze the effects of fund parity on party system size.Footnote 10 To correct for heteroskedasticity, we obtain robust standard errors by employing Huber–White sandwich robust variance estimators.Footnote 11 Last, regression diagnostics of studentized residuals and Cook’s distance indicate that three observations are extreme statistical outliers, namely Albania 2005, Belgium 2003, and Belgium 2014. To account for this, we include dummies for these observations in the models.Footnote 12

Empirical analysis

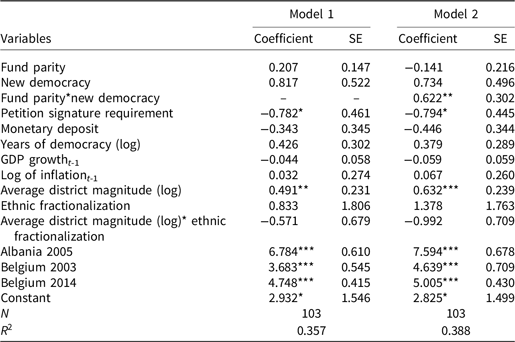

The results of our first regression models can be seen in Table 1. Model 1 takes into account the independent effects of the variables, while Model 2 includes all of the variables and the interaction term. As the results in Model 1 show, the coefficient of fund parity is positive, but it does not attain statistical significance. This result challenges Potter and Tavits’ finding to some extent, suggesting that there is no strong statistical evidence of an association between fund parity and party system size, at least in the European context.Footnote 13 Moreover, the coefficient of new democracy is positive, but it is also statistically insignificant. This finding shows a weak association between new democracy and party system size.

Table 1. Effects of fund parity on party system size in Europe

Note: The dependent variable is effective number of parties in votes. Entries are OLS regression coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses (two-tailed tests).

* P ≤ 0.1.

** P ≤ 0.05.

*** P ≤ 0.01.

More importantly, the results in Model 2 offer considerable support for our hypothesis. The coefficient is positive and statistically significant for the interaction term of fund parity*new democracy. This indicates that, in a country with political financing rules that provide more equal conditions for electoral competition, party system size tends to increase when this country is a new democracy. In other words, fund parity matters for enlarging party system size in post-communist European democracies. This evidence suggests that it is necessary to consider the multiplicative effects of fund parity for party financing and political contexts.

In both models, the coefficient of the average district magnitude is positive and statistically significant. Due to the inclusion of an interaction term, the coefficient of the average district magnitude suggests that in a hypothetical situation where no ethnic cleavage exists (ethnic fractionalization equals zero), a larger average district magnitude increases the effective number of parties. Moreover, petition signature requirement has a negative association with the dependent variable in Model 1 and Model 2. Countries that require a number of petition signatures for party registration tend to have a smaller party system, and evidence that is similar to this finding can be found in many previous studies (Tavits, Reference Tavits2008; Rashkova, Reference Rashkova2014b; Su, Reference Su2015).

Surprisingly, the results in Table 1 demonstrate that many control variables do not have statistically significant associations with ENPV. Against theoretical expectations (Amorim Neto and Cox, Reference Amorim Neto and Cox1997), the interaction term of ethnic fractionalization and average district magnitude does not have a statistically significant association with ENPV. The finding also shows that coefficients for monetary deposit, years of democracy, ethnic fractionalization, and the two economic performance variables fail to attain statistical significance across the two models.

Our main hypothesis is supported by the empirical results presented above. We show that the variation of party system size in Europe can be explained by the level of fund parity of political financing rules depending on different political contexts. To better understand the substantive effect of the interaction between fund parity and new democracy, we conduct a marginal effect estimation to predict the ENPV based on the results of Model 2.

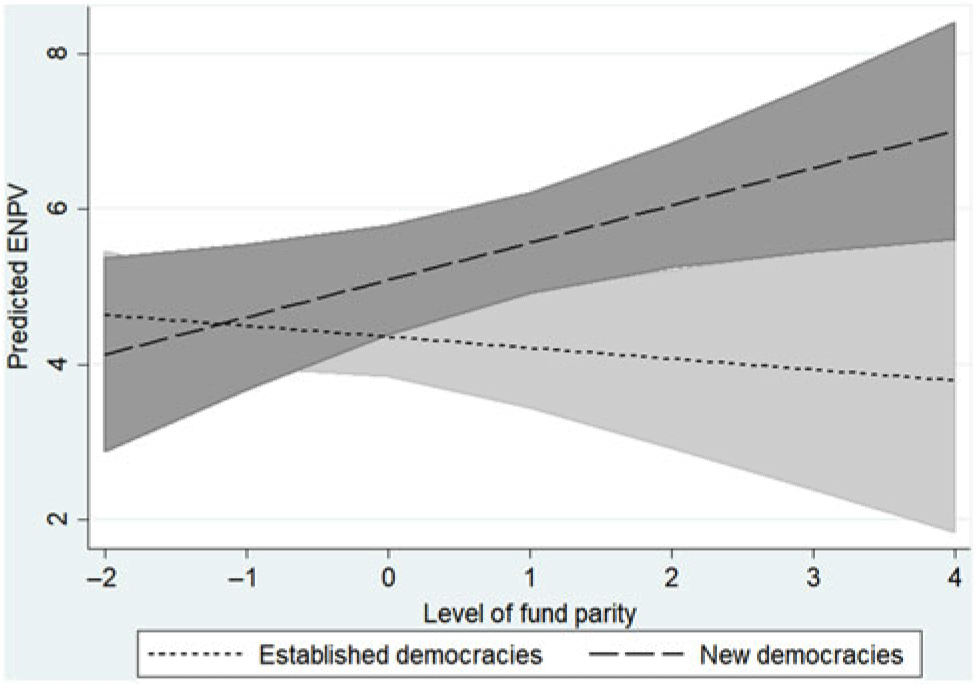

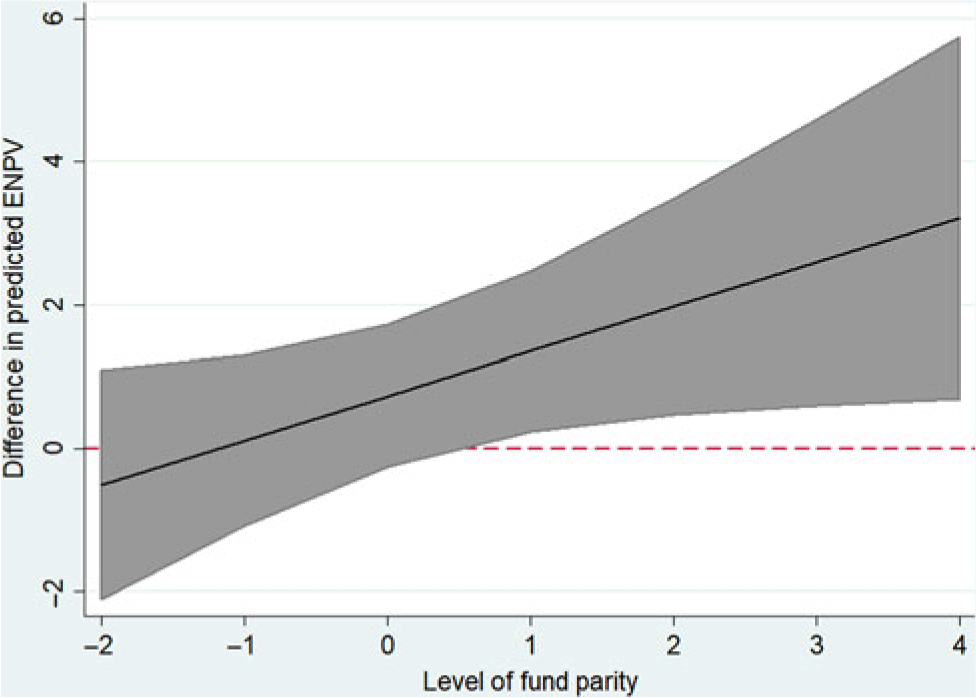

Figure 1 presents the predicted ENPV for established democracies and new democracies at different levels of fund parity. For new democracies, holding the values of other variables in the model at their means, the predicted ENPV changes from 4.1 to 7.0 when we move from the lowest observed value of fund parity (−2) to the highest observed value (4). In contrast, for established democracies, the predicted ENPV does not change much when we move from the lowest value of fund parity to the highest. Figure 2 reports a test of difference in ENPV between the two types of countries at different levels of fund parity. It shows that the difference is statistically insignificant when fund parity is at low levels, but this difference becomes statistically significant when a threshold of fund parity is surpassed at a value of 0. Taken together, these two figures show that when the level of fund parity is high, a new democracy has a larger ENPV than an established democracy. When a new democracy adopts political financing rules that make larger parties more electorally advantageous, its ENPV will not significantly differ from an established democracy that also adopts similar political financing rules. However, as ENPV for new democracies increases with more fund parity, the difference in ENPV for established and new democracies becomes statistically significant when the fund parity reaches a much higher level.

Figure 1. Predicted effective number of parties in votes (with 95% confidence interval) by political contexts at different levels of fund parity.

Figure 2. Difference in predicted effective number of parties in votes (with 95% confidence interval) by political contexts at different levels of fund parity.

Last, we conduct a robustness check to ensure that our empirical findings are not sensitive to coding decisions for the dependent variable. Specifically, we use effective number of parties in seats for our dependent variable and re-estimate our models. The results of the re-estimation are consistent with those reported in Table 1.

Addressing potential endogeneity

A potential threat to the inference for our analysis stems from the possibility that party laws are not exogenous to party system characteristics. This may be particularly true for the case of political financing rules because political elites might choose to change this institution to make sure that they benefit from the reforms. For instance, in countries with fewer parties, political elites might adopt more restrictive rules about funding to reduce the level of party system fragmentation so that they could secure their current electoral advantage. We thus undertake a number of tests to determine whether there is indeed a causal relationship between fund parity and effective number of parties.

We follow Potter and Tavits (Reference Potter and Tavits2015) to conduct two tests. First, we consider whether the ENPV in the previous election would influence the years for which we have measurements for fund parity. If we see a clear negative relationship between the ENPVt-1 and the current value of fund parity, then it might suggest a potential endogenous relationship. The test indicates that there appears to be a weak relationship (r = 0.24) between the ENPVt-1 and the current level of fund parity for the current election.

Another attempt at addressing concerns about endogeneity is to examine cases in which fund parity changed between measurement years. If the selection of political financing regulations is truly endogenous to the ENPV, then it is expected that a country with a higher ENPV value tends to adopt increasingly permissive political financing rules. We identify 33 instances in our dataset that changed the fund parity metric between 2003 and 2012 or/and between 2012 and 2018. If there is an endogeneity problem, the relationship between the average ENPV during the interval of measurement years and the change of fund parity should be strong and positive. The test shows that this correlation coefficient across the 33 instances in our dataset is weak (r = 0.07). In short, we demonstrate that the average party system size during the interval of measurement years is not a good predictor of the direction of the change of fund parity.

A stronger test of the causal order between fund parity and ENPV can be performed by using instrumental variable regression. Because our theory involves the interaction effect of two variables, the IV approach would be difficult to apply for our purposes. Based on the core idea of the IV approach, however, it is possible to estimate a control function (CF) model for addressing this issue of endogeneity for our study. The CF model takes into account unobserved factors that can potentially influence fund parity and ENPV. To employ the CF model, it is necessary to use an instrumental variable that is related with fund parity but not with ENPV. In our dataset, we find that the variable of log of GDP per capita would be a good instrument because it relates to fund parity (r = −0.49) but not to ENPV (r = 0.03).

The estimation of the CF model involves two regression estimations. In the first stage, we use OLS to regress the endogenous variable (i.e. fund parity) with the instrument (i.e. log of GDP per capita), new democracy, and the control variables. Next, we predict residuals for the first stage regression, which are the unobserved heterogeneity. In the second stage, we employ an OLS model on ENPV with the following variables on the right-hand side of the equation: the predicted residuals, fund parity, new democracy, fund parity*new democracy, and the control variables. This step ensures that the unobserved heterogeneity is controlled in the second regression. The results of the CF model show that the coefficient of fund parity*new democracy is negative and statistically significant at P ≤ 0.05 level. Overall, we are confident that our findings are robust across different models.

Conclusion

The question of how money affects politics and political competition draws vast interest not only from scholarly but also from policymaking perspectives. Scholars have established that there is a relationship between certain regulations and party system development. Yet, whether and to what extent political funding affects party competition still remain a question of contention. While most party regulation, and especially funding-related regulation, was inspired by the goal of the European Union and other international organizations to fight political corruption by increasing transparency and by offering public funding schemes, we further argue that a party system tends to be larger if a country adopts a design of political financing rules with more fund parity, namely, providing fair competition opportunities for smaller and new parties. In this paper, we propose that this is especially evident in new democracies, where political entrepreneurs have fewer alternative options to participate in the political game to their counterparts in established ones. This is a result of the facts that these countries are significantly poorer and political entrepreneurs have less incentive to form political parties when they lack the resources to do so, and they also have less knowledge and experience than their Western counterparts. Consequently, we argue that an equal financial playing field is expected to result in more political parties, especially in those democracies.

We tested our proposition about the interactive effects of fund parity and new democracies on data from 43 European democracies. The idea behind the variable of fund parity is that it combines a number of rules on specific financial matters, where the larger the value of this variable is, the more equal conditions that the political financing rules provide for small and new parties. Our empirical analysis demonstrates that the variation of party system size in European democracies can be explained by the combination of fund parity and particular political contexts. Specifically, we show that fund parity matters in explaining party system size in new democracies but not in established democracies. The mechanism behind this result suggests that because many post-communist countries lack long experiences of democracy, and because many elites in these countries have lower financial ability, when the financing rules provide a more equal chance for small and new parties access to campaign resources, the elites might have more incentives to form parties because their parties are more likely to sustain once established. This finding extends Potter and Tavits’ (Reference Potter and Tavits2015) theory of fund parity by showing the effect of political finance on party competition in a more nuanced way. More specifically, the current study shows that it is not the existence of party finance regime per se that matters, but rather, that it is an equalizing party finance regime in a less-equal political and financial environment that is important. A lesson to be taken from this research is that if intergovernmental organizations, who want to promote democracy through elections, such as IDEA, want to increase the chance of political inclusiveness both on the elite and on the citizen level, they need to assure that the party finance regimes adopted are ones that provide equal opportunities to all contestants, or even better, favor small players and new comers.

While the paper does not test the cartel party thesis directly, it provides a complementary perspective to the thesis. Our empirical results imply that larger parties tend to benefit from the manipulated system of financial rewards that make these parties more advantageous, and this is particularly evident for new democracies. In other words, the cartel party thesis works mainly in new democracies but not in established democracies. This advocates for a number of regulation reconsiderations and suggests that perhaps, it is not a ‘one size fits all’ type of regulation that creates a level playing field in democracy and that we may need to reconsider the design of some of the recently adopted party regulation guidelines at the international level, if we want to stimulate different results.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773919000316

Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate the feedback and suggestions from Magda Giurcanu, Fernando Casal Bertoa, Zsuzsanna Blanka Magyar, the two anonymous reviewers of this article, Professor Carlos Closa Montero and Professor Matt Qvortrup. This work was partially supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (grant number 106-2628-H-004 -004 -MY3).