Introduction

In the European Parliament, national political parties from across the European continent form transnational party groups, which presupposes that its members occupy roughly the same corner of the political space or at least share some ideological traits. An important task for members of the party groupings in the EP is to shape the direction of (further) European Union (EU) integration, which makes it crucial that members of transnational party groups interpret EU integration in similar ways. Therefore, we study how parties’ positions towards European integration relate to their positions on other important issues, and how this varies across EP elections, and between European regions. We find that European integration is understood and interpreted differently by parties across the EU. The longstanding interpretation of EU integration as a mainly economic issue in Southern Europe diminished after the peak of the migration crisis, and EU integration is related to immigration issues in Central-Eastern Europe while this is not the case in the other regions.

In most EU member states, the political issue space is multi-dimensional, with at least one socioeconomic and one cultural dimension (see, e.g., Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006; Teperoglou and Tsatsanis, Reference Teperoglou and Tsatsanis2011; Krouwel Reference Krouwel2012). There is an extensive academic debate on particularly the substance and interpretation of the cultural dimension which is not only connected to religious matters anymore, but also incorporates salient issues regarding immigration, multiculturalism, and European integration (see, e.g., Hooghe, Marks and Wilson, Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Bornschier, Reference Bornschier2010; Hutter, Grande and Kriesi Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016). However, some have argued that two dimensions cannot capture the complexity of the current political climate, and that party positions are better understood by plotting them along three issue dimensions: an (economic) left-right dimension, a social-cultural dimension, and an EU-integration dimension (Bakker, Jolly and Polk, Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012; Costello, Thomassen and Rosema, Reference Costello, Thomassen and Rosema2012). This would imply that parties’ positions towards EU integration are more or less orthogonal to positions on other cultural issues.

EU integration has become a more contentious issue in national elections in many countries over the last decade (Kneuer, Reference Kneuer2019). In addition, the Brexit referendum in the UK resonated across Europe and the anti-EU political mobilization by populist and extreme right-wing parties is also up in many countries (see Gómez-Reino and Llamazares Reference Gómez-Reino and Llamazares2013; Hutter, Grande and Kriesi, Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016; Hernández and Kriesi, Reference Hernández and Kriesi2016). However, the different stages of European integration have created fluctuating levels of saliency of EU issues across time and space (Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016), and dimensionality underlying parties’ issue positions may vary between member states (Louwerse and Otjes, Reference Louwerse and Otjes2012; Otjes and Louwerse, Reference Otjes and Louwerse2014). Moreover, the association between EU-integration positions of both voters and parties and their positions on other issues is context-dependent: under some circumstances EU positions are more related to economic views, whereas under other circumstances they are more related to cultural stances (Otjes and Katsanidou, Reference Otjes and Katsanidou2017; Wheatley and Mendez, Reference Wheatley and Mendez2019; Schäfer, Popa, Braun and Schmitt, Reference Schäfer, Popa, Braun and Schmitt2021). Based on these previous studies, we presuppose that the association between parties’ EU-integration positions on the one hand, and their positions on either the cultural or economic dimension on the other hand is affected by the three major crises that hit the EU around and between the three most recent EP elections of 2009, 2014, and 2019: the financial crisis that started in 2007, the migration crisis that deepened in 2015 when more than a million migrants and refugees crossed into Europe, and the ongoing climate crisis.

We analyse datasets that are uniquely suitable for analysing the associations between various policy issues over time and across regions, collected through pan-European Vote Advice Applications that include issue positions of political parties on a wide range of issues (Krouwel and van Elfrinkhof, Reference Krouwel and van Elfrinkhof2014). With the EU Profiler/euandi Trend File data (Reiljan et al., Reference Reiljan, Ferreira Da Silva, Cicchi, Garzia and Trechsel2020) we aim to contribute to recent studies on the impact of crises on party competition in Europe (e.g. Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019; Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Popa, Braun and Schmitt2021) in several ways. First, this dataset allows studying parties’ positions at the European level on issues that are similarly measured in the EP elections of 2009, 2014, and 2019. Where previous literature studied the impact of the economic crisis, we additionally study the impact of the migration crisis that peaked after the EP 2014 elections. Second, this dataset includes the near universe of political parties from all 28 member states (still including the UK then) and can therefore be used to study the impact of crises both over time and across space. Third, the specific methods that were used to collect the VAA data – like the combination of parties’ self-placement and expert coding based on multiple sources – have several advantages for the purpose of our study (see the “Data and Methods” section).

In the next paragraphs, we first discuss the general dimensional structure of party competition in Europe, and how we think parties’ positions towards EU integration may be differently associated with other issues across time and space. Second, we explore the dimensional structure underlying parties’ issue positions in the three most recent EP elections, to see whether the EU integration issues form their separate dimension. Third, we outline our analytical strategy and test our hypotheses. Finally, we discuss the results in light of previous literature and their implications.

The European political party space

Departing from Lipset and Rokkan’s (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967) seminal work on social cleavages, the political space is often depicted as basically two-dimensional, with a salient socioeconomic left-right dimension and a moral-cultural dimension (Krouwel Reference Krouwel2012). The interpretation of this cultural dimension varies widely and this may suggest that the political party space in European democracies – and by extension in European parliament – has a higher dimensionality than the two-dimensional model. In fact, several authors have suggested there is a separate EU-integration dimension (Marks and Steenbergen Reference Marks and Steenbergen2002; Bakker, Jolly and Polk, Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012; Costello, Thomassen and Rosema, Reference Costello, Thomassen and Rosema2012). Others, like Hooghe, Marks and Wilson (Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002), have argued that issues related to nationalism – including EU issues – align strongly with other cultural issues into a GAL-TAN dimension, which juxtaposes environmental (green), alternative, and libertarian (progressive) issue positions against traditional (conservative), authoritarian, and nationalistic issue positions. Similarly, Bornschier (Reference Bornschier2010) coined the dimensions ‘libertarian-universalistic versus traditionalist-communitarian’, while Kitschelt (Reference Kitschelt1994) used the broad ‘libertarian-authoritarian’ labels for this cultural dimension. The increasing politicization of EU integration (see Gómez-Reino and Llamazares Reference Gómez-Reino and Llamazares2013; Hernández and Kriesi, Reference Hernández and Kriesi2016; Hutter, Grande and Kriesi, Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016; Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kneuer, Reference Kneuer2019) – with the strong emergence of anti-EU populist parties and the Brexit referendum – makes it more likely that a separate EU-integration dimension is present. Since we focus on European Parliament elections, we assume EU-related issues to play an even more prominent role than in national elections (see also Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Popa, Braun and Schmitt2021).

Time-varying associations between EU integration and other issue positions

Our main goal is to analyse the association between parties’ EU-integration positions and their positions on other salient issues. The central premise of our study is that parties are more likely to relate their position on EU integration to their position on another issue, when and where this other issue is more salient. This may be for ideological reasons, when they perceive that the particular issue can only be adequately tackled at the supranational level – by increasing EU integration – or with more national sovereignty. This is arguably the case for the financial crisis of 2008, the migration crisis of 2015, and the ever-more pressing climate crisis. Parties’ Eurosceptic stances may be ideologically rooted in opposition to ongoing market liberalization for left-wing parties but also in opposition towards transferring national sovereignty and fear of rising immigration rates for right-wing parties (e.g. De Vries and Edwards, Reference De Vries and Edwards2009; Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018).

Moreover, parties who ‘own’ a particular issue may also have strategic incentives to exploit the saliency of this issue in EP elections, by linking this issue to their EU-integration position during EP election campaigns. It has to be noted that realigning European integration positions with positions on other issues is relatively difficult for mainstream parties, and therefore initial change mainly comes from rising parties that give EU integration greater salience, for example, radical right and green parties (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; see also De Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020). If these parties have been successful in previous elections, mainstream parties tend to adjust their positions as well (see, e.g., Williams and Ishiyama, Reference Williams and Ishiyama2018; Meijers and Williams, Reference Meijers and Williams2020). Altogether, we expect the three (economic, migration, climate) crises to have affected the association between parties’ EU-integration positions and other issue positions.

First, between the 2009 and 2014 EP elections, the economic crisis and the subsequent government interventions – primarily austerity measures, welfare state retrenchment, and increasing economic precarity for many – dominated the political discourse and shifted relative power between mainstream and anti-establishment parties (Hernández and Kriesi, Reference Hernández and Kriesi2016). Second, in between the 2014 and 2019 European elections, issues related to immigration had taken centre stage due to the substantial influx of refugees from the Middle East and Africa. Relatedly, existing and new populist right parties put extra emphasis on curbing refugee intake which triggered reactions from the major parties and thus impacted party competition (De Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020). Although the link between anti-immigration and EU-integration attitudes did not strengthen in the minds of voters during the migration crisis (Stockemer, et al., Reference Stockemer, Niemann, Unger and Speyer2020), this link may still have increased for parties, since they combine their issue positions in a more coherent way than voters do. Around the same time, the UK voted to leave the EU in the so-called Brexit referendum, which could have emboldened the anti-EU political forces across the continent. Third, the consequences of the climate crisis became increasingly clear over the last decade, which could impact on the saliency of climate issues and was reflected in a strong showing of green, environmental parties in the 2014 European elections. Because of the timing of these crises, we assume that (1) economic issues were most salient in the 2014 EP elections as compared to 2009 and 2014, (2) immigration issues were most salient in 2019 as compared to 2009 and 2014, and (3) the environmental issues increased in salience with each subsequent election. Since we assume that in EP elections political parties relate their position on the EU-integration dimension to their position on salient issues that cannot be solved in a national context, we formulate the following three hypotheses:

H1: Parties’ positions on the EU-related issues will be more strongly related to the socioeconomic dimension in 2014, as compared to 2009 and 2019.

H2: Parties’ positions on the EU-related issues will be more strongly related to the cultural dimension in 2019, as compared to 2009 and 2014, and in particular to parties’ positions on immigration issues.

H3: Parties’ positions on the EU-related issues will be increasingly related to the cultural dimension over the period 2009–2019, and in particular to parties’ positions on climate issues

Hypotheses 2 and 3 both relate to the association between the EU dimension and the cultural dimension, but they presuppose different underlying explanations (saliency of immigration or climate issues). We will come back to how we distinguish these underlying explanations in the analytical strategy and results section.

Similarity across different EU regions

On top of our assumption that the economic, refugee, and climate crises changed the saliency and interrelatedness of particular issue dimensions over time, we acknowledge that economic and migration crises may have hit different regions asymmetrically. There should therefore have been substantial variation in issue saliency and structure of party competition across regions over time.

Previous studies have already shown dissimilarity in the dimensional structure of the political space across EU member states. Party positions in some European countries could be captured by a single dimension, whereas in other countries two or three dimensions were necessary (Louwerse and Otjes, Reference Louwerse and Otjes2012; Otjes and Louwerse, Reference Otjes and Louwerse2014). Also, as Hutter et al. (Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016) have shown, the different stages of European integration have created ‘punctuated politicization’ and fluctuating levels of saliency of EU issues across time and space. Such variation in issue saliency and dimensional structure between member states was already witnessed in voter opinions based on the EUProfiler 2009 VAA data (Kleinnijenhuis and Krouwel, Reference Kleinnijenhuis, Krouwel, Bühlmann and Fivaz2016). Following the suggestion by Bakker, Jolly and Polk (Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012), our main focus is the extent to which EU integration and other issues are interrelated in different ways across Europe, rather than a dichotomous approach of assuming the presence or total absence of distinct dimensions.

Several studies showed that for voters the EU-integration issue is in complex and differential ways related to often multiple issue dimensions (Otjes and Katsanidou, Reference Otjes and Katsanidou2017; Wheatley and Mendez, Reference Wheatley and Mendez2019). We know that political elites – who write up the party platforms and issue positions – are more coherent in their political stances, and that the dimensional structure and issue saliency may differ from that of voters. However, we expect differences across regions in Europe with regard to how parties compete over the EU. These differences may be explained by the saliency of economic and cultural issues in a particular country, as a consequence of levels of immigration and/or the extent to which the country was affected by the Eurozone crisis (Otjes and Katsanidou, Reference Otjes and Katsanidou2017; Taggart and Szczerbiak, Reference Taggart and Szczerbiak2018; Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019). The dissimilarity across European regions of the severity of the economic and migration crises should have made particular issue dimensions more salient in particular places at particular time points. Previous studies showed that parties’ positions towards EU integration were increasingly determined by their position on the cultural dimension between 1958 and 2008 (Prosser, Reference Prosser2016), especially after the signing of the Maastricht Treaty that transformed the nature of the EU from a merely economic to a broader political project (Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Popa, Braun and Schmitt2021). This is in line with our central premise since new cultural issues, like immigration and multiculturalism, have become increasingly salient in the political debate over the last decades (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006). However, this saliency may be different across European regions.

Based on the 2014 European Election Survey, Otjes and Katsanidou (Reference Otjes and Katsanidou2017) concluded that the extent to which voter opinions towards European integration were correlated with the economic dimension depends on the extent to which a country was affected by the Eurozone crisis. They showed that in regions hardest hit by the economic crisis, like Southern Europe, European integration was more linked to the economic dimension, while in other regions this was not the case. These results were replicated by Wheatley and Mendez (Reference Wheatley and Mendez2019) using EUvox VAA data from that same 2014 European election. Similarly, Hutter and Kriesi (Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019) found an effect of the economic crisis on the structure of national party competition in EU-member states. The combined political and economic crisis in the South had increased the saliency of economic issues and issues related to democratic renewal and reforms, including European integration (see also Statham and Trenz, Reference Statham and Trenz2015). Moreover, the Eurozone crisis had a particularly strong impact on Euroscepticism in those countries that were hit hardest by the bailout packages and austerity measures (Taggart and Szczerbiak, Reference Taggart and Szczerbiak2018). To illustrate this, economic arguments were most prevalent to justify pro- and anti-EU attitudes for Greek parties during the height of the economic crisis (Vasilopoulou, Reference Vasilopoulou2018).

In the North-West of Europe, economic issues gained in saliency as well, yet to a lesser extent than in the South (Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019). Due to the fact that the North-West was less severely impacted by the financial crisis compared to the Southern countries and that subsequent economic austerity was much more destructive for welfare state arrangements in the South, it is logical to expect differences between the North and South. In Central- and Eastern Europe, the economic dimension was less pronounced as most parties converged on a pro welfare state, statist development model, partly due to the communist legacy. The crisis did not substantially alter the saliency of economic issues in this region (Hernández and Kriesi, Reference Hernández and Kriesi2016; Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019). This different pattern in saliency of economic issues – highest in SE, less in NWE, and lowest in CEE – could affect how these issues aligned with the European integration dimension. It has to be noted that Schäfer et al. (Reference Schäfer, Popa, Braun and Schmitt2021) showed that this association between economic and EU-integration positions in Southern Europe has always been present and did not substantially change after the start of the financial crisis. However, based on the results of the other studies mentioned above, and on the fact that we use a different dataset that includes a wider sample of EU member states and political parties, we think it is worthwhile to perform an additional test of this expectation.

Altogether, based on the timing of the economic crisis and its asymmetrical impact across regions, we hypothesize the following:

H4: Parties’ positions on the EU-related issues will be more strongly related to the socioeconomic dimension in 2014 in Southern Europe, as compared to North-Western and Central- and Eastern Europe.

Otjes and Katsanidou (Reference Otjes and Katsanidou2017) found that voters’ opinions regarding EU integration were strongly related to issue stances on the cultural dimension in Northern countries with the highest net immigration before the migration crisis in 2015. Similarly, Wheatley and Mendez (Reference Wheatley and Mendez2019) found that in the North of Europe, voters’ opinions regarding EU integration are strongly related to attitudes towards immigrants and gay rights, suggesting that EU integration is associated with one broad and encompassing cultural dimension in this region. At the party level, Hutter and Kriesi (Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019) found important differences between regions regarding the saliency of the cultural dimension. During the economic crisis years spanning 2009–2016, cultural issues diminished in saliency in Southern Europe, while the relevance of cultural issues increased in North-Western- and Central-Eastern Europe. In line with this, Schäfer et al. (Reference Schäfer, Popa, Braun and Schmitt2021) showed that parties’ positions towards EU integration were exclusively shaped by cultural issues in North-Western European countries until 2014.

However, when the migration crisis hit Europe around 2015 this disproportionately impacted the Southern European countries, as they were hit by the stream of refugees trying to reach the EU over the Mediterranean Sea. This was especially true after the EU-Turkey deal through which other legal routes for migrants were closed. This could explain why Conti, Marangoni and Verzichelli (Reference Conti, Marangoni and Verzichelli2020) found that Euroscepticism in Italy increased after the outbreak of the Eurozone crisis, but was strongly linked to anti-immigration sentiments by political actors during the 2019 EP elections. Altogether, we hypothesize:

H5: Parties’ positions on the EU-related issues will be more strongly related to the cultural dimension in North-Western Europe in 2009 and 2014, as compared to Southern Europe and Central- and Eastern Europe.

H6: Parties’ positions on the EU-related issues will be more strongly related to the cultural dimension in Southern Europe in 2019, as compared to North-Western Europe and Central- and Eastern Europe.

Data and methods

We used data from the EU Profiler/euandi Trend File (2009–2019), made available by the Robert Schuman Centre of Advanced Studies at the European University Institute, which were collected during the EP election campaigns of 2009, 2014, and 2019 (Reiljan et al., Reference Reiljan, Ferreira Da Silva, Cicchi, Garzia and Trechsel2020). They include party positions on a wide range of items that were measured in a similar way across all EU-member states.

Using VAA data has several advantages for the purpose of our study. The VAAs measured party positions by combining self-placement of parties with expert coding in an attempt to combine the strengths of both methods and counterbalance their respective weaknesses (Trechsel and Mair, Reference Trechsel and Mair2011; Krouwel and van Elfrinkhof, Reference Krouwel and van Elfrinkhof2014; Garzia, Trechsel and Sio, Reference Garzia, Trechsel and De Sio2017). The inclusion of parties themselves is especially important when it comes to measuring issue positions of smaller or newer parties. Since rising parties are deemed important for affecting the nature of party competition (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018), this feature of the data is particularly important for the purpose of our study. Further, to reduce the number of missing values, the expert coding is not only based on the manifestoes for the specific EP election but also on other sources, like statements of party representatives in parliament or media and on the latest national election manifestoes. Finally, analyses of cross-national variation in issue positions suffer less from biases regarding the timing within election cycles, since the VAAs are developed in proximity to the elections, and from biases regarding institutional and regulatory constraints, since all parties compete for representation in the same institution under the same rules (Trechsel and Mair, Reference Trechsel and Mair2011; Garzia et al., Reference Garzia, Trechsel and De Sio2017).

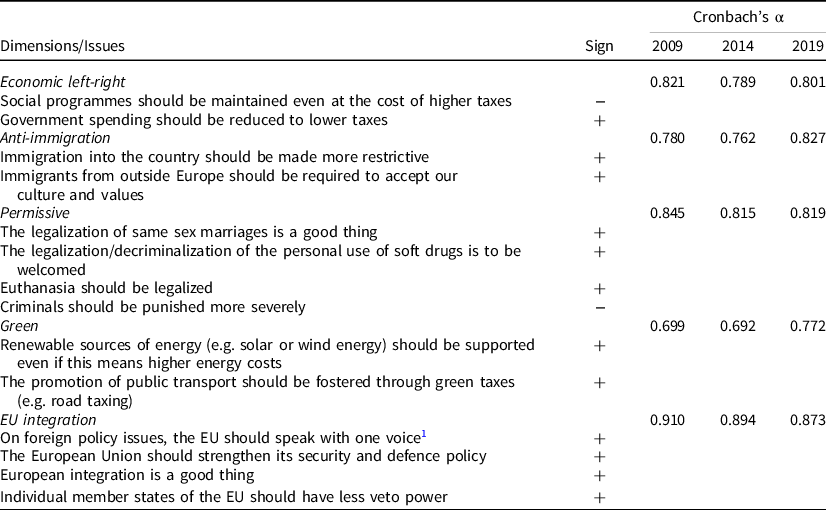

Fifteen of the issues were similarly measured across the three elections and across all member states, which makes the data uniquely suitable for analysing the parties’ issue positions across elections and regions. We do have the near universe of cases as all major and minor parties in each of the 28 member states are included. Although all VAAs included 30 statements, we only use the 15 items that are measured similarly across time and across countries, because our aim is to draw comparisons between EU regions and between elections. Table 1 provides an overview of all cross-national, cross-election items in the VAAs.

Table 1. Overview the issues belonging to the five issues scales and the reliability of the scales

Before we explicitly test our hypotheses, we explored the structure of the political space across the EU over time by performing an exploratory factor analysis for each of the three EP elections. This gives some insight into whether parties’ EU issue positions are in general either related to cultural or economic issues, or whether they form their own separate underlying dimension. The results are discussed in the next paragraph. It has to be noted that these analyses only give insight into the dimensionality underlying parties’ issue positions in the EU as a whole, and cannot be used as an explicit test of our hypotheses. We could not perform these analyses separately for each of the three EU regions, because the number of parties per region per election with a valid score on all 15 items of interest would be too low (ranging from 75 parties in 2019 in NWE to 13 parties in 2009 in CEE). To test our hypotheses, we therefore perform OLS regression models in which we predict parties’ EU-integration positions from their positions on other issues, and we interact the effects of these issues with region and election dummies. The results of this analysis are discussed after the description of our exploratory analysis.

Exploring the dimensional structure

We followed three steps in the factor analysis for each of the elections. First, an initial unrotated solution was performed to infer the number of underlying dimensions by inspecting the scree plot and the eigenvalues of the unrotated factors. For all three elections, the scree plot and eigenvalues suggest two underlying dimensions (see online Appendix 1). Second, a varimax rotation was performed. The structure matrices were inspected to determine whether the underlying factors are correlated. For all three elections, these matrices suggest that the two factors are weakly correlated, and therefore an oblique (promax) rotation was performed to interpret the factor loadings. The pattern coefficients of the factor analyses with oblique (promax) rotation can be found in online Appendix 1.

The exploratory factor analyses show a similar structure for all three elections. The two socioeconomic items, the two immigration items, the climate items, and the four moral-religious items all load on the first factor. Four items regarding EU integration, EU foreign policy, EU security policy, and EU members’ veto rights all load on the second factor. The item regarding EU taxes (‘The EU should acquire its own tax raising powers’) cross-loaded on both dimensions (see also Louwerse and Otjes, Reference Louwerse and Otjes2012) and was therefore dropped from further analyses. Altogether, the results suggest a two-dimensional structure with one broad left-right dimension, encompassing both economic and cultural issues, and one EU dimension. That the economic and cultural issues all seem to constitute one broad left-right dimension is not in line with most of the literature about national party competition that we discussed above. However, the most important result for the purpose of our study is that the EU issues do indeed form a separate dimension. A remarkable result of the three factor analyses is that the correlation between the two factors strongly increased between 2009 (r = 0.094), 2014 (r = 0.241), and 2019 (r = 0.328). With this knowledge, we proceed to the main analysis in which we test whether this increased association between the two dimensions is driven by specific issues (economic, immigration, environmental), and whether this differs between European regions.

Analytical strategy

To test our hypotheses, we performed multilevel regression analyses with parties nested in elections and countries to predict parties’ positions on the EU-integration dimension by their positions on the other issues. Based on the results of the factor analyses, we constructed an EU integration scale that consists of four items regarding EU foreign policy, security and defence policy, integration in general, and veto rights of member states. The reliability of this scale is very high in each election (Cronbach’s α: 0.873–0.910).

Since we formulated hypotheses on the association between parties’ positions on EU integration issues on the one hand, and economic issues and cultural issues on the other hand, we cannot simply proceed with the broad left-right dimension that was suggested by the factor analyses. Instead, we constructed separate scales for each of the four components that constitute this broad left-right dimension. First, the economic left-right scale consists of two items, both related to the trade-off between government spending and taxes. These two items form a reliable scale in all three elections (Cronbach’s α: 0.789–0.821). Second, the anti-immigration scale consists of two items, one regarding restricting immigration and one regarding the assimilation of immigrants. These items form a reliable scale in all three elections as well (Cronbach’s α: 0.762–0.827). Third, we constructed a green scale to be able to explicitly test Hypothesis 3. This scale consists of two items, one regarding renewable energy sources and the other about public transport and green taxes. This scale is less reliable in 2009 and 2014 (Cronbach’s α just below 0.7), while it is reliable enough in 2019 (Cronbach’s α: 0.772). Fourth, the old-cultural, or permissive, scale consists of four items, regarding same-sex marriage, euthanasia, legalization of soft drugs, and punishment of criminals. The reliability of this scale is consistently high as well (Cronbach’s α: 0.815–0.845). Distinguishing between these ‘old’ cultural issues and immigration issues is in line with Otjes and Katsanidou’s (Reference Otjes and Katsanidou2017) study on voters’ positions (see also Kleinnijenhuis and Krouwel, Reference Kleinnijenhuis, Krouwel, Bühlmann and Fivaz2016). We have no specific hypothesis about these issues, but we will use the scale later in a robustness check. Table 1 shows which items we assigned to which issue scales, and how reliable these scales are.

Before formally testing our hypotheses, we present descriptive analyses of the association between parties’ positions on EU integration and the other issues in 2009, 2014, and 2019. Then we tested Hypotheses 1–3 each in four separate steps. In Model 1a, we predict parties’ EU-integration positions from their positions on the economic left-right issues, and we include dummy variables for elections (2009 as reference) and regions (NWE as reference). In Model 2a, we interact the effect of the economic left-right issues scale with the election dummies to see whether the association with the EU-integration position changed over time. Then we additionally account for the possibility that economic left-right issues and EU integration are non-linearly related. In Model 3a, we included a squared term for the economic left-right scale. In Model 4a, we interacted this economic left-right scale and the non-linear term with the election dummies. We repeated these steps with the anti-immigration scale to test H2 (see Models 1b–4b) and the green scale to test H3 (see Models 1c–4c) instead of the economic left-right scale. The complete results of all models are included in the regression tables in Appendix 2. We tested the robustness of these time-varying associations by including the effects of the abovementioned three issues, plus the remaining permissive issues, simultaneously in one model to account for the correlations between these issues (see Models A1–A4 in Table A7, plus Figure A2 in online Appendix 3).

Then we tested whether the associations between EU integration on the one hand and the economic left-right issues or the anti-immigration issues on the other hand differed over time between the three European regions. We tested Hypothesis 4 by interacting the economic left-right scale with the election dummies and the region dummies. Similarly, we tested Hypotheses 5 and 6 by interacting the anti-immigration scale with the election dummies and the region dummies. We tested the robustness of the results of these models in two steps. First, we accounted for any non-linear associations that we observed earlier in Models 3a or 3b. Second, we included the cross-regional time-varying effects of the four issues simultaneously in one model, to account for the correlations between the issues (see Model A5 in Table A8 and Figure A3 in online Appendix 3).

We dropped the observations that had missing values on one of the issue scales,Footnote 2 which means that we analysed a sample of 625 observations (party-election combinations) out of the total sample of 768 observations.

Results

Time-varying associations

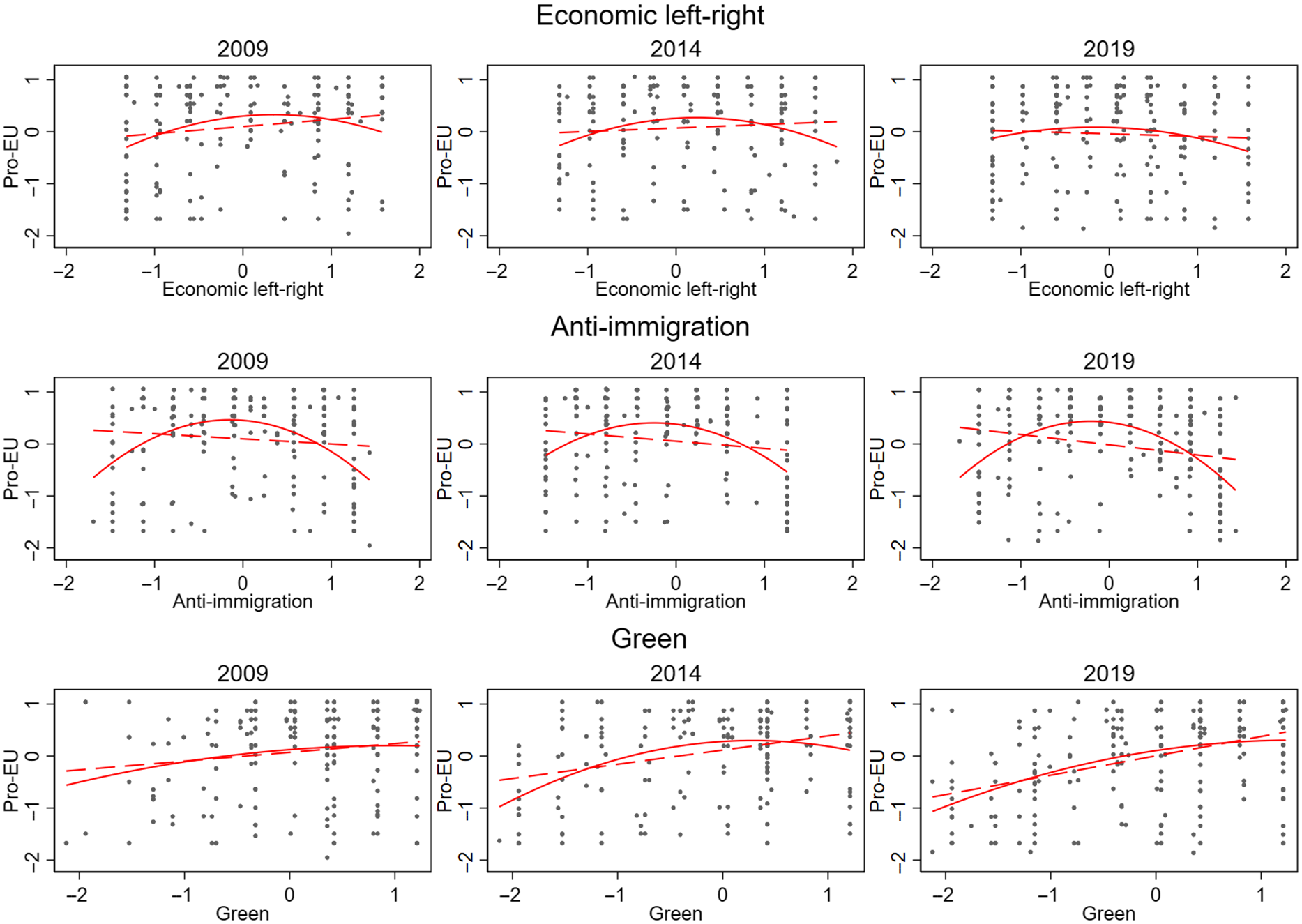

The descriptive plots in Figure 1 show a slight positive association between economic left-right positions and EU-integration positions in 2009, which seems to slightly decrease with each subsequent election. Models 1a–4a formally test Hypothesis 1.

Figure 1. Bivariate associations between economic, anti-immigration, and green issues on the one hand and EU-integration positions on the other hand, for each election year, with linear and non-linear fitted lines.

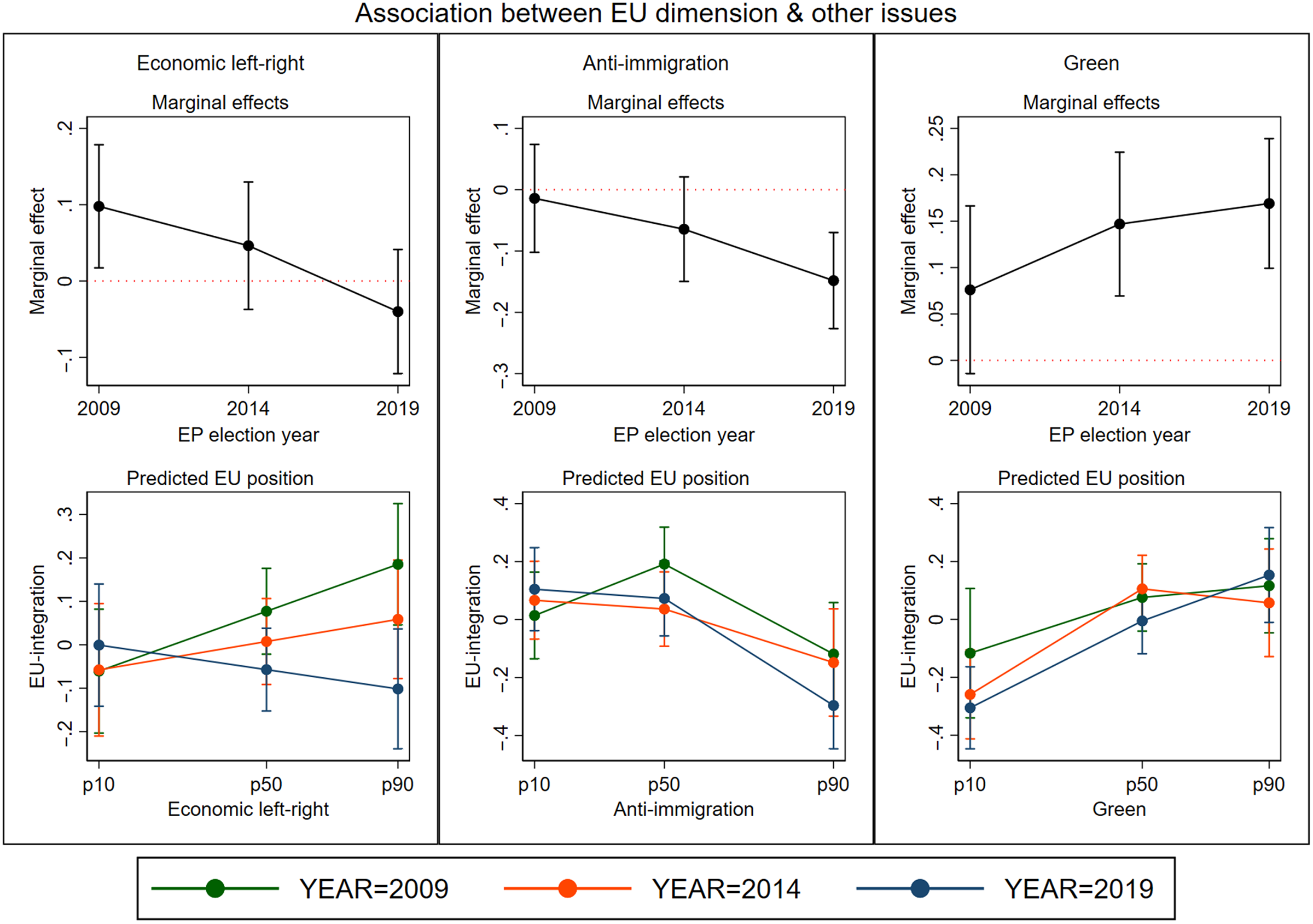

Model 1a shows that – in the EU as a whole – parties’ positions on the economic issues (b = 0.035; SE = 0.034) are not significantly related to their position on the EU-integration dimension. Furthermore, our models show that parties from CEE scored significantly higher on the EU-integration dimension, as compared to parties from NWE, and that parties scored significantly lower on EU integration in 2019, as compared to 2009. Model 2a explicitly tests Hypothesis 1 by interacting economic issue positions with year dummies to predict EU-integration positions, which significantly improved model fit (likelihood ratio test vs M1a: χ2 = 9.93; P = 0.007). The results indicate that the association between parties’ economic position and EU-integration position was significantly positive in 2009, and was significantly weaker in 2019. The marginal effect of economic left-right position by election is visualized in the upper-left panel of Figure 2. For a more substantive interpretation, the lower-left panel visualizes the predicted EU-integration position as a function of economic-left right position. Together, these graphs show that the association between economic left-right and EU-integration positions was significantly positive in 2009 and disappeared afterwards. This is not in line with Hypothesis 1. Additionally, Model 3a does not indicate that the association between economic left-right and EU positions is non-linear (b Econ. L-R = 0.038; SE = 0.034; b Econ L-R 2 = −0.020; SE = 0.032), and Model 4a does not show evidence that this would be different in any specific election. In sum, we found no support for Hypothesis 1.

Figure 2. Marginal effects on economic, anti-immigration, and green issues on EU-integration positions, and predicted EU-integration position as function of these issues, by election year. Note: p10 = 10th percentile, p50 = 50th percentile, p90 = 90th percentile in the distribution of the independent variable.

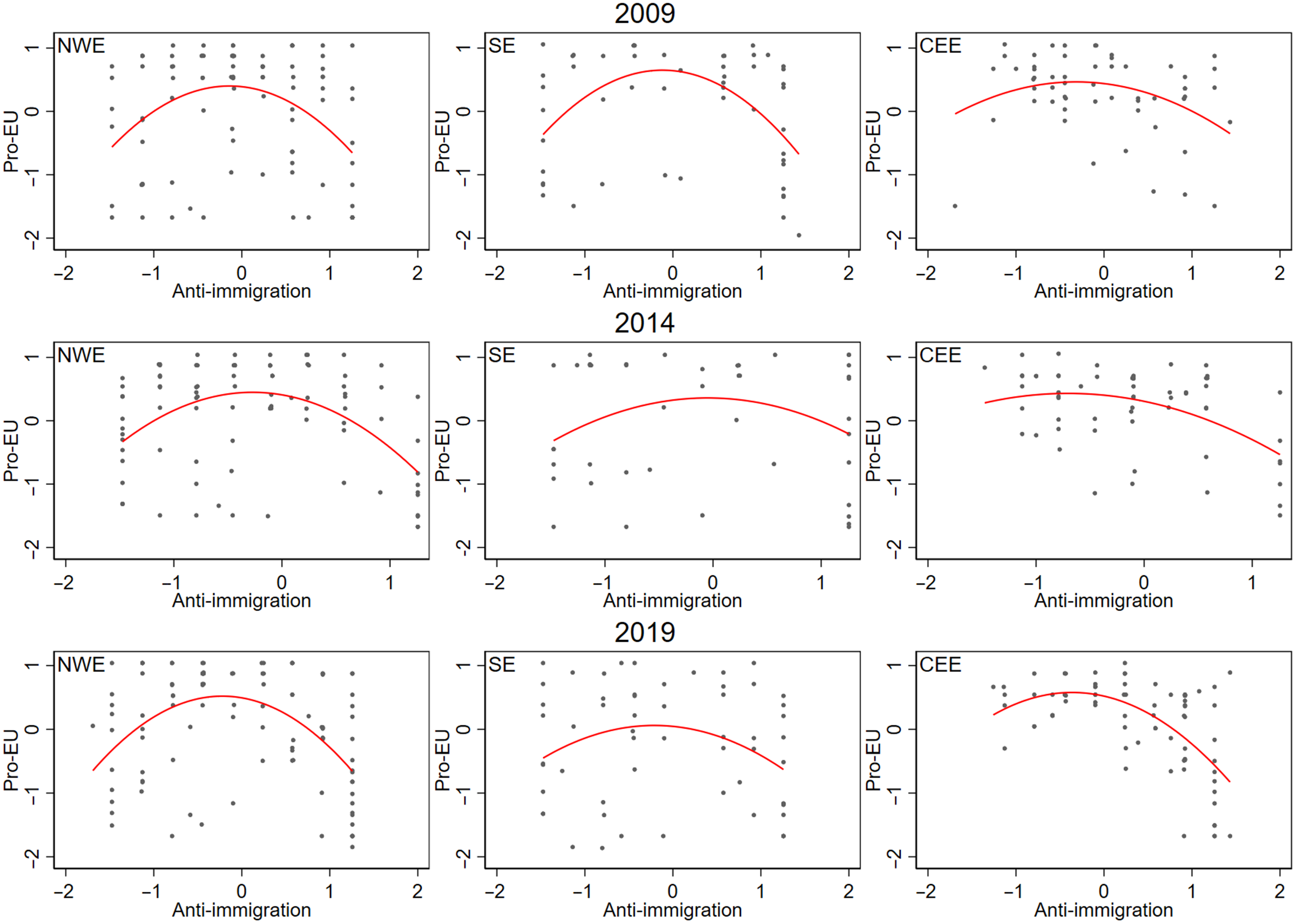

The descriptive plots in Figure 1 show a slight curvilinear association between anti-immigration and EU-integration positions in all three elections, with the parties on both ends of the anti-immigration scale being the least positive towards EU integration. We expected the effect of anti-immigration to be especially pronounced in 2019 (H2). Models 1b–4b formally test this hypothesis.

Model 1b shows a small negative association between anti-immigration and EU-integration positions (b = −0.089, SE = 0.034). Model 2b includes interactions with election dummies, which significantly improved model fit (likelihood ratio test vs M1b: χ2 = 8.48; P = 0.013). This association between anti-immigration and EU positions was not yet present in 2009 and was not significantly different in 2014, but had significantly strengthened by 2019. The centre panel of Figure 2 visualizes that the association between anti-immigration and EU-integration positions was only significant in 2019, which is in line with Hypothesis 2. Model 3b indicates that the effect of anti-immigration positions is curvilinear (b anti-immigration = −0.103, SE = 0.034; b anti-immigration 2 = −0.114, SE = 0.036), which significantly improved model fit (likelihood ratio test vs M1b: χ2 = 8.98; P = 0.002). Model 4b includes interactions between the curvilinear effect and election dummies (likelihood ratio test vs M3b: χ2 = 10.77; P = 0.029). Results are visualized in Figure 2. This shows a slight curvilinear association in 2009, no association in 2014, and a slight negative association between anti-immigration and EU-integration positions in 2019. In sum, we found support for Hypothesis 2.

The descriptive plots in Figure 1 show a slight positive association between green and EU-integration positions that seems to increase with each subsequent election, which is what we expected (H3). Models 1c–4c formally test this hypothesis. Model 1c shows a positive association between green and EU-integration positions (b green = 0.071, SE = 0.051). Model 2c shows that this association did not significantly differ between elections. The marginal effects in Figure 2 indicate that the association between green and EU positions was significantly positive in 2014 and 2019, but not yet in 2009. However, including the time-varying effects did not significantly improve the model fit (likelihood ratio test vs M1c: χ2 = 3.48; P = 0.176). Model 3c includes the non-linear effect of green positions, which significantly improved model fit (likelihood ratio test vs M1c: χ2 = 4.80; P = 0.03), and indicates a slight curvilinear relationship. Model 4c tests whether this curvilinear effect changed over time, but including these interactions did not improve model fit (likelihood ratio test vs M3c: χ2 = 4.82; P = 0.306). In sum, we found no support for Hypothesis 3.

In an additional analysis (see online Appendix 3), we tested the robustness of these patterns by modelling them simultaneously, and also taking the parties’ positions on the ‘old cultural’ permissive issues into account. Model A1 tests the effects of all four issue scales simultaneously. Model A2 includes time-varying effects, which does not improve model fit (likelihood ratio test vs MA1: χ2 = 11.81; P = 0.160). Model A3 takes non-linear effects into account (likelihood ratio test vs MA1: χ2 = 13.24; P = 0.004) and confirms a positive effect of economic left-right positions, and a curvilinear effect of anti-immigration and green positions, and additionally shows that permissive positions are positively related to EU-integration positions. Model A4 includes the time-varying effects for these four issues, but this did not improve model fit (likelihood ratio test vs MA1: χ2 = 18.52; P = 0.070). The results are summarized in Figure A2 in online Appendix 3. The effect of economic left-right still disappeared over time (although not yet in 2014). However, the association between anti-immigration and EU positions in 2019 is no longer significant, so we should be careful in accepting Hypothesis 2.

In sum, first, we found no support for our hypothesis that the association between economic and EU-integration positions was strongest in 2014 (H1). Second, we found some support for our hypothesis that the association between anti-immigration and EU-integration positions was strongest in 2019 (H2), but this finding was not robust to controlling for parties’ positions on the other issues. Third, we found no support for our hypothesis that the association between green and EU positions increased over time (H3).

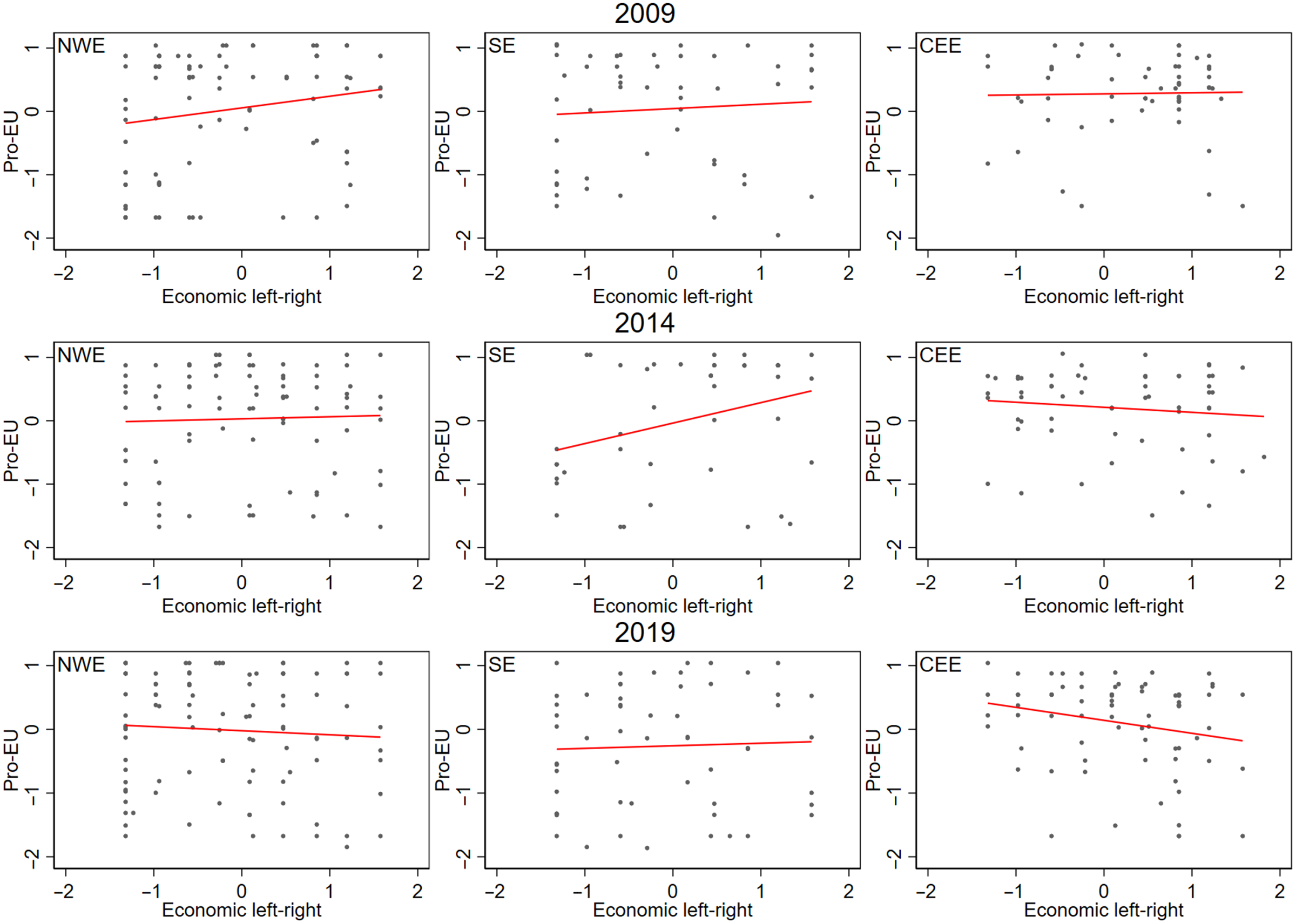

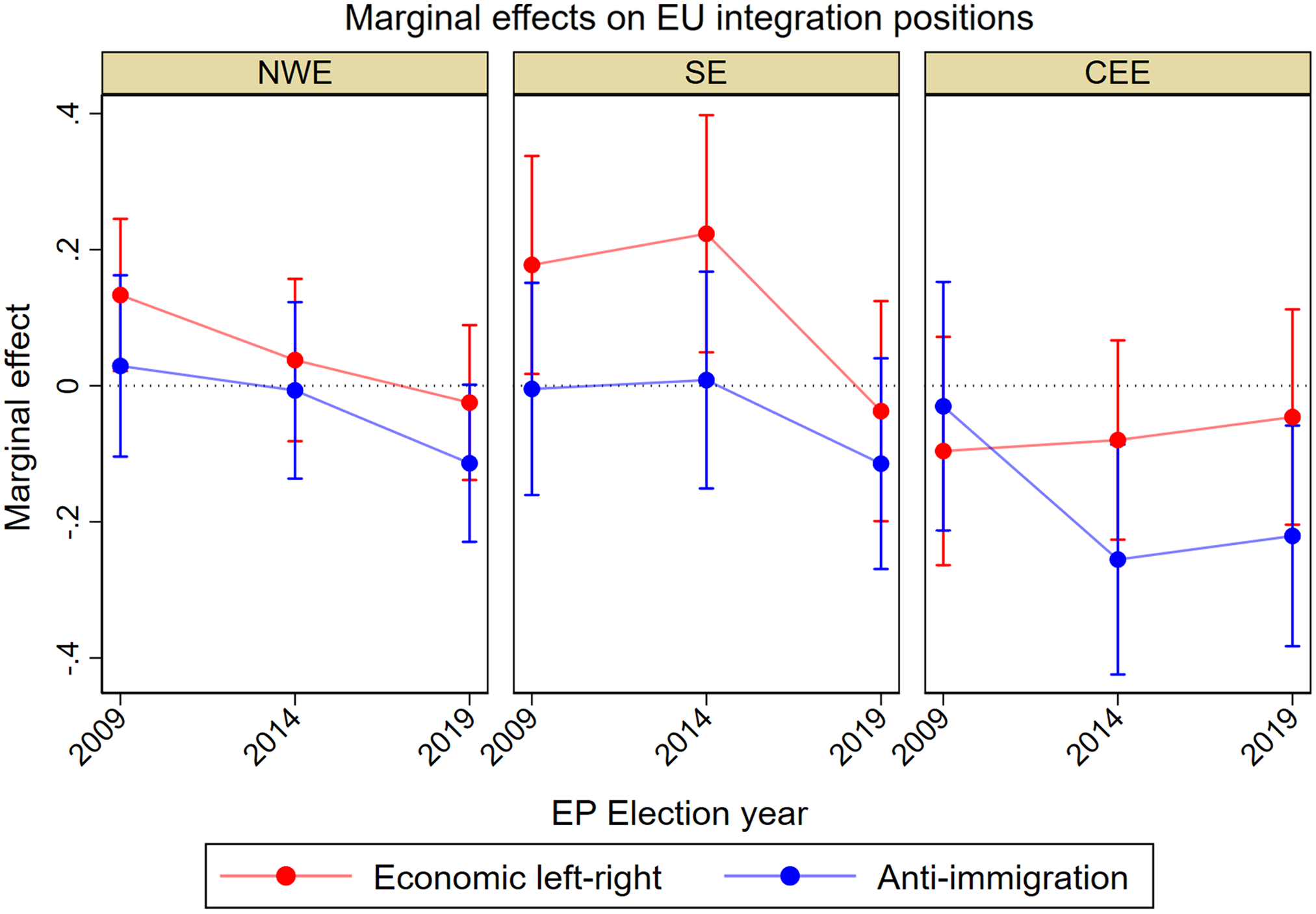

Similarity across regions

What stands out from the bivariate associations in Figure 3 is a seemingly positive association between economic and EU-integration positions in Southern Europe in 2014, which would be in line with our Hypothesis 4. To test this hypothesis, Model 5 includes the three-way interactions between economic left-right position, election dummies, and region dummies, which significantly improved the model fit compared to the model with only time-varying effects (likelihood ratio test vs M2a: χ2 = 23.66; P = 0.008). The results are visualized in Figure 5. Parties’ economic left-right positions were not significantly related to their EU-integration positions in CEE in all three elections. However, in NWE the relationship was significantly positive in 2009. In SE, the relationship was significantly positive in 2009 and 2014. This is largely in line with Hypothesis 4, which predicted a stronger association in 2014 in SE as compared to the other regions. Additionally, this association was already present in both NWE and SE right after the start of the financial crisis in 2009, but the relationship disappeared in NWE whereas it remained in SE.

Figure 3. Bivariate associations between economic and EU-integration positions, for each election year by region, with linear fit lines.

The bivariate associations in Figure 4 suggest that the association between anti-immigration and EU positions did not substantially change over time in NWE, that the curvilinear association in SE slightly weakened over time, and that the association became increasingly negative in CEE. These patterns are not in line with either Hypothesis 5 or 6. Model 6 tests both these hypotheses by interacting anti-immigration positions with both region and election dummies, which significantly improved the model fit compared to the model with only time-varying effects (likelihood ratio test vs M2b: χ2 = 19.54; P = 0.034). Figure 5 shows no significant association in any of the elections between anti-immigration and EU-integration positions in both NWE and SE, which rejects both Hypotheses 5 and 6. Moreover, a clear negative association between anti-immigration and EU positions was present in CEE in both 2014 and 2019. Model 7 takes the non-linear effect of anti-immigration positions into account, but this did not significantly improve the fit of the model (likelihood ratio test vs M6: χ2 = 13.75; P = 0.034). Our conclusions regarding Hypotheses 5 and 6, therefore, do not substantively change once non-linear associations are taken into account.

Figure 4. Bivariate associations between anti-immigration and EU-integration positions, for each election year by region, with linear fit lines.

Figure 5. Marginal effects of parties’ positions on economic and anti-immigration issues on parties’ EU-integration position, by region and election.

Again, we tested the robustness of the patterns by modelling them simultaneously, and also taking the parties’ positions on the other issues (green and permissive) into account. Figure A3 in online Appendix 3 visualizes the marginal effects of economic and anti-immigration positions, based on this model with cross-regional time-varying effects of green and permissive issues included. The only difference with the uncontrolled marginal effects from Figure 5 is the effect of anti-immigration positions in SE in 2019. Figure A3 suggests that pro-EU and anti-immigration positions became positively associated in Southern Europe in 2019. It means that – when positions on economic, green and permissive issues are held constant – there is a slight positive association between anti-immigration and pro-EU positions. Since these economic, green, and permissive issues are all correlated with anti-immigration positions, this result merely reflects a hypothetical situation and should not be overinterpreted. The other patterns – the disappearance of the association between economic and EU positions in SE after 2014, and the emergence of an association between anti-immigration and EU positions in CEE – are robust to this additional test.

Conclusion and discussion

We studied how parties’ positions regarding EU integration are related to their positions on other important issues, and to what extent this varies over time and across three European regions. In doing so, we used the EU Profiler/euandi Trend File with data on parties’ policy positions on 15 issues that were measured similarly across all EU member states in the three most recent EP elections. Based on previous studies, we presupposed that the association between parties’ EU-integration positions on the one hand, and their positions on the cultural and economic dimensions on the other hand, was affected by the three major crises that hit the EU around and between the EP elections of 2009, 2014, and 2019: the economic crisis, the migration crisis, and the climate crisis. We found no clear evidence that these crises significantly altered the associations between parties’ EU-integration positions and other issues when we analysed the EU as a whole. Rather, the economic crisis and the migration crisis impacted these associations asymmetrically across three European macro regions (North-Western-, Southern-, and Central-Eastern Europe).

Before we explicitly tested our hypotheses, we explored the dimensional structure underlying 15 issue positions in the EU as a whole for which we had data across three elections for all parties. This analysis suggests a two-dimensional structure with one broad left-right dimension, encompassing both economic and cultural issues, and one separate EU dimension. That the economic and cultural issues all seem to constitute one broad left-right dimension is not in line with most of the literature on national party competition (e.g. Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1994; Hooghe, Marks and Wilson, Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006; Bornschier, Reference Bornschier2010). However, it may reflect that our EU-wide analysis does not capture significant variation between countries, since party positions in EP elections may be unidimensional in some countries, whereas in other countries two or three dimensions underlie these positions (Otjes and Louwerse, Reference Otjes and Louwerse2014).

The most important result for the purpose of our study is that the EU issues in general form a separate dimension (see also Bakker, Jolly and Polk, Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012; Costello, Thomassen and Rosema, Reference Costello, Thomassen and Rosema2012). Since we formulated hypotheses on the association between parties’ positions on EU integration issues on the one hand, and economic issues and cultural issues on the other hand, we constructed separate scales for each of the four components that constitute the broad left-right dimension.

We expected that parties’ positions on EU integration would be more strongly related to socioeconomic issues in 2014, as compared to 2009 and 2019, as a result of the financial crisis and subsequent welfare state retrenchments (H1). We also expected that parties’ positions on EU integration would be more strongly related to the cultural dimension – particularly to immigration issues – in 2019 as a consequence of the migration crisis. Moreover, we hypothesized parties’ EU-integration positions to be more strongly related to the cultural dimension – particularly to climate issues – in each subsequent election. However, our results do not show such changes in the association between these issues and the EU dimension. Therefore, Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 were not corroborated. It seems that the structure of party competition over EU integration in EP elections is rather immune to external shocks.

Our analysis of regional differences, however, did show that these crises asymmetrically affected the association between cultural and economic issues on the one hand and the EU dimension on the other. In line with our expectations, the EU dimension was more strongly associated with the socioeconomic issues in 2014 in Southern Europe, as compared to North-Western and Central- and Eastern Europe (H4). This is in line with previous studies on the relationship between economic positions and Euroscepticism after the Eurocrisis (Otjes and Katsanidou, Reference Otjes and Katsanidou2017; Vasilopoulou, Reference Vasilopoulou2018; Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019; Wheatley and Mendez, Reference Wheatley and Mendez2019). However, this association between economic and EU-integration positions in Southern Europe was already present and did not intensify after the start of the Eurocrisis, which replicates Schäfer et al.’s (Reference Schäfer, Popa, Braun and Schmitt2021) findings with a different dataset that includes a wider sample of EU member states and political parties.

In addition, we assumed immigration to be a more salient issue in North-Western countries – due to the higher net immigration rates – compared to the other two regions before the migration crisis. That is why we expected that for North-Western parties, EU-integration positions would be more strongly related to their positions on immigration issues in 2009 and 2014, compared to parties in South, Central-, and Eastern Europe (H5). Parties’ anti-immigration positions were not significantly related to EU-integration positions in NWE, so Hypothesis 5 was not supported. However, when the migration crisis hit Europe around 2015, this disproportionately impacted the Southern European countries, Greece and Italy particularly, as they were more affected by the stream of refugees trying to reach the EU over the Mediterranean Sea. Therefore, we expected the strongest association between the immigration issues and EU dimension in the South in 2019, as compared to the other two regions.

This was not supported by our results as we found no significant association between anti-immigration and EU positions in Southern Europe. Only when positions on economic, green, and permissive issues are held constant, is there a slight positive association between anti-immigration and pro-EU positions, which merely reflects a hypothetical situation and should not be overinterpreted. Contrastingly, Central-Eastern European parties with stronger anti-immigration positions were more Eurosceptic in 2014 and 2019, which we did not anticipate. However, this is in line with Hooghe and Marks’ (Reference Hooghe and Marks2018) notion that immigration became a more salient issue after the start of the migration crisis in CEE, and with Taggart and Szczerbiak’s (Reference Taggart and Szczerbiak2018) conclusion that the migration crisis did have a particularly strong impact on parties’ Euroscepticism in Central-Eastern Europe. Perhaps this is explained by parties in Central-Eastern Europe perceiving that the EU forces their countries to take in refugees. The abovementioned results were robust to the inclusion of non-linear effects of anti-immigration on EU-integration positions (see online Appendix 3).

Altogether, our results are in line with previous studies suggesting a longstanding association between EU-integration positions and economic issues in Southern Europe (Taggart and Szczerbiak, Reference Taggart and Szczerbiak2018; Vasilopoulou, Reference Vasilopoulou2018; Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Popa, Braun and Schmitt2021). Despite the increased saliency of economic issues and European integration in the aftermath of the Eurocrisis in Southern Europe (Statham and Trenz, Reference Statham and Trenz2015; Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019), our results reconfirm that the Eurocrisis did not abruptly affect the nature of party competition over EU integration (see Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Popa, Braun and Schmitt2021). Instead, the migration crisis may have made the longstanding interpretation of EU integration as a mainly economic issue disappear in Southern Europe.

Future studies could build upon these findings by explicitly testing whether issue salience can explain how the EU dimension relates to other issues. Moreover, it would be worthwhile to study the extent to which our conclusion holds when other explanations for how political parties compete over European integration are considered. For example, variations in cleavage structures from which political competition in different parts of Europe originate, different compositions of electorates, different economic structures, and variation in EU-entry, may also explain substantial cross-national differences in how EU integration is related to other issues in the three regions during EP elections. Future studies on over-time and cross-regional variation in the politicization of EU integration could therefore more elaborately consider the role of historically underlying national conflict structures (Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2016). In line with this, we investigated the differences between regions, but it may be even more informative to formulate expectations for differences between individual countries (see Taggart and Szczerbiak, Reference Taggart and Szczerbiak2018; Petsinis, Reference Petsinis2020). In doing so, one can more specifically study the impact of immigration rates and economic performance at the country level (e.g. Hernández and Kriesi, Reference Hernández and Kriesi2016). Further, economic, cultural (new/old), and environmental issue positions are not the only substantive reasons why parties may be more or less positive about EU integration. As Taggart and Szczerbiak (Reference Taggart and Szczerbiak2018) showed, parties may also use frames of democracy/sovereignty, or purely national matters, to formulate their position towards EU integration. Finally, it would be worthwhile to specifically study the role of new parties in competition over EU integration, since they are particularly likely to give EU integration greater salience and/or relate it to new issues (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; see also De Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020).

Notwithstanding these limitations, the main take way of this study is that European integration means different things and is understood and interpreted differently by parties across the EU. We argued that this is driven by asymmetric impacts of the Eurocrisis and migration crisis across the EU. Our results suggest that the migration crisis diminished the longstanding interpretation of EU integration as a mainly economic issue in Southern Europe, and that EU integration is clearly related to immigration positions in Central-Eastern Europe while this is not the case in the other regions. Cross-regional differences in the interpretation of EU integration may hinder transnational party groups to accurately represent a coalition of voters across a wide range of member states on this important topic for the future of the EU. Recognizing that EU-integration positions may be associated with other issue positions differently between regions is therefore important to recognize for parties that seek to work together in transnational party groups. This is also important to understand for scholars who aim to understand and interpret EU policy making and to assess how political parties ‘translate’ their national party competition to the EU level.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the journal editors for their helpful comments, and we are very grateful to the team at the Robert Schuman Centre of Advanced Studies at the European University Institute for making the EUprofiler/euandi Trend File dataset publicly available.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773921000242