Introduction

Recent decades have seen dramatic increases in women occupying positions of political power. Such developments have been welcomed in part as a means of achieving better outcomes for women through public policy. An emerging empirical literature lends support to this proposition (Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras, Reference Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras2014; Chattopadhyay and Duflo, Reference Chattopadhyay and Duflo2004; Swiss et al., Reference Swiss, Fallon and Burgos2012). However, female representatives do not always promote or implement policies that benefit women (Wängnerud, Reference Wängnerud2009; Franceschet and Piscopo, Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008). Hence, there is a need to understand the circumstances under which descriptive representation (greater proportions of women in the legislature) translates into substantive representation (improved policy outcomes for women).

We investigate the link between descriptive and substantive representation in multiple ways. First, we argue that having more women in the legislature should tend to promote better outcomes for female citizens given the higher likelihood of shared interests – particularly in societies with circumscribed gender roles. Second, we argue that the link between descriptive and substantive representation is stronger when female citizens are more actively engaged in politics and society; such engagement can facilitate “gendered accountability” even in the absence of free and fair elections. Finally, we hold that the institutional rules and procedures through which representatives are chosen are also consequential.

Our empirical analysis looks across countries in sub-Saharan Africa, which has seen the largest increase in women’s political representation in recent years. Many African countries are also characterized by considerable gender inequality, which manifests in ways that public policy could address (Duflo, Reference Duflo2012). Furthermore, entrenched gender norms and sex segregation in the division of household labor increase the likelihood of gender being a salient cleavage when it comes to policy priorities. Our analysis therefore focuses on the outcomes of two policy areas that we argue women disproportionately prioritize: infant and child mortality. These outcomes also correspond to widely agreed upon international development priorities, lending our study concrete policy relevance.

Analyzing data from the 1960s to 2015, we find that having more women in the legislature is robustly associated with lower numbers of infant and children deaths and that this association appears to be driven in part by greater spending on healthcare. We also find a statistically significant interaction between the share of women in the legislature and women’s participation in civil society and media when it comes to reducing infant mortality, suggesting that female politicians are more likely to further women’s policy priorities when female citizens are monitoring their actions. Furthermore, we show that female descriptive representation is only associated with improved outcomes in countries that have gender quotas. However, the mere adoption of gender quotas does not appear to influence the outcomes we study. We interpret this as suggesting we are picking up effects beyond broader norms of gender equality; at the same time, such norms may be necessary for representation in the legislature to go beyond tokenism. Our results are also confined to countries with some degree of proportionality in their electoral systems.

That there are few other cross-country studies of the relationship between women’s political representation and policy outcomes benefiting women may reflect the challenge of causal inference that this type of analysis entails. For instance, women’s representation tends to be correlated with voter preferences (Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras, Reference Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras2014), and other country-specific factors may affect both the election of women and the enactment of policies that benefit them. We account for such threats to causal inference to the best of our abilities by controlling for variables whose omission could bias our results and including country and year fixed effects. We also test a variety of model specifications, including system-GMM models that are well suited to deal with slow-moving variables and potential endogeneity.

This paper contributes to the literatures on representation, accountability, and public goods provision. We extend existing theories built and tested mainly in the Western world and propose a new analytical framework for achieving substantive representation. We argue that the link between descriptive and substantive representation is not automatic and that women’s presence in the legislature is unlikely to lead to substantive changes absent certain institutional and societal conditions. Importantly, we provide one of the first quantitative tests in the literature about the importance of women’s civil society organizations in advancing women’s policy priorities. Thus, our work provides empirical evidence for those interested in improving public policy outcomes while also providing arguments for the benefits of advancing the role of women in politics.

This paper proceeds as follows. The next section outlines our theoretical framework, after which we describe our empirical strategy and data. We then present our results and discuss their implications as concerned to the present study and future research.

Gendered accountability: achieving women’s substantive representation

Hannah Pitkin’s (Reference Pitkin1967) influential volume presents four main “views” or dimensions of representation. First, formal representation refers to the rules and procedures used to select representatives; descriptive representation captures the similarity (in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, etc.) between representatives and the people they purportedly represent; symbolic representation reflects the degree to which a representative “stands for” the represented; and substantive representation relates to the actions taken on behalf of, or in the interest of the represented. Pitkin presents an integrated notion of these views; however, most empirical work on representation has tended to examine one or two of them in isolation. Footnote 1

Our notion of “gendered accountability” attempts to fill this gap by delineating conditions under which descriptive representation is most likely to generate substantive representation. We argue that this link will be strengthened when female citizens are more actively engaged in politics and civil society (which may be a consequence of symbolic representation). We also show how this link is conditioned by particular aspects of formal representation – the institutional rules and procedures through which female representatives are chosen.

The politics of presence

The expectation that female politicians will better represent the concerns of female constituents requires men and women to diverge in terms of their policy preferences (Phillips, Reference Phillips1995). Empirical evidence indeed suggests women tend to favor redistribution more than men, even controlling for political ideology (Alesina and Giuliano, Reference Alesina, Giuliano, Benhabib, Bisin and Jackson2011; Iversen and Rosenbluth, Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006; Finseraas et al., Reference Finseraas, Jakobsson and Kotsadam2012). Scholars have also identified gender gaps with respect to partisan alignment and voting behavior (Inglehart and Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2000; Corder and Wolbrecht, Reference Corder and Wolbrecht2016). In low-income countries, recent scholarship suggests that divergent preferences may be even more common (Gottlieb et al., Reference Gottlieb, Grossman and Robinson2016; Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, Josefsson, Mattes and Mozaffar2019).

To explain these divergent preferences, scholars highlight differences in the social structures in which men and women live (Khan, Reference Khan2017; Sapiro, Reference Sapiro1981; Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge1999), including the fact that women are socialized to be caretakers of others (Hutchings et al., Reference Hutchings, Valentino, Philpot and White2004). Thus, they tend to be more directly concerned with child health and nutrition (Box-Steffensmeier et al., Reference Box-Steffensmeier, De Boef and Lin2004; Sapiro, Reference Sapiro1998). Therefore, women disproportionately suffer as a result of weak reproductive and child health services (Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras, Reference Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras2014). Such concerns often lead women to favor policies that improve these outcomes (Duflo, Reference Duflo2012). Importantly, Gottlieb et al. (Reference Gottlieb, Grossman and Robinson2016) show that in contexts where women are more vulnerable, the gender gap in preferences widens. Further, the changing roles of women in societies as a result of declining fertility rates, higher divorce rates, and increasing independence of women from their husbands as they enter the workforce also motivate women to support policies that alleviate their traditional roles of taking care of others (Edlund and Pande, Reference Edlund and Pande2002).

Divergent preferences can have real consequences for the enactment and implementation of policies. For instance, the introduction of female voting rights in early 20th century United States qualitatively changed the the political agenda, leading to a sharp increase in health expenditure and a drop of 8–15% in child mortality (Miller, Reference Miller2008). In Africa, Gottlieb et al. (Reference Gottlieb, Grossman and Robinson2016) find that women are significantly more likely to say that health is a top priority the government should address and invest in improving.

Gendered policy preferences can manifest in campaigns and party platforms, with female politicians campaigning more on issues that matter to women, and their election helping to ensure that such concerns are represented in government. Indeed, empirical studies find female candidates talk more frequently about social issues during campaigns, including healthcare, when compared to their male counterparts (Kahn, Reference Kahn1993; Evans and Clark, Reference Evans and Clark2016; Mechkova and Wilson, Reference Mechkova and Wilson2019).

Further, we can still expect female politicians to better represent the interests of female voters even if they campaign on platforms that are not particularly gendered or on party tickets that promote broader interests. As Phillips (Reference Phillips1995: p. 44) points out, “representatives… have considerable autonomy, which is part of why it matters who those representatives are.” As she argues, under a strict definition of representation, politicians only truly represent their constituents on the issues that were explicitly debated during the election campaign. On all other issues, they necessarily rely on their own judgement or prejudice. If we expect that women and men tend to differ on average in terms of their judgments and prejudices, female constituents should be better represented by female politicians even if those politicians do not campaign on “women’s” issues.

Female legislators can act to promote women’s interests by putting women’s issues on the political agenda (Devlin and Elgie, Reference Devlin and Elgie2008), bringing them up during parliamentary debates (Yoon, Reference Yoon2011), and building coalitions across party lines, with grass-root movements and with their male counterparts (Johnson and Josefsson, Reference Johnson and Josefsson2016). Ultimately, this concentrated effort on part of female parliamentarians helps for the adoption of policies that address the issues women face through adopting specific legislation (Wang, Reference Wang2013) and allocating more money from the budget for specific programs that benefit women (Clayton and Zetterberg, Reference Clayton and Zetterberg2018). Importantly, this evidence for the different actions women parliamentarians take comes from case studies of democratic and non-democratic contexts.

Considerably fewer studies have examined how female representation affects the outcomes of public policy – particularly in less developed settings. Notable exceptions include Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras (Reference Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras2014), who find increased women’s political representation is associated with improved public provision of antenatal and childhood health services in India. Also in India, Chattopadhyay and Duflo (Reference Chattopadhyay and Duflo2004) show that female local leaders tend to initiate projects that reflect their female constituents’ concerns. Looking across 102 developing countries, Swiss et al. (Reference Swiss, Fallon and Burgos2012) find that descriptive representation is associated with increased immunization rates and infant and child survival.

Diagonal accountability and substantive representation

While shared preferences help to explain why female politicians may be more likely to implement policies that benefit female citizens, there are also various instances in which descriptive representation does not beget substantive representation. We argue that female politicians will be more likely to implement policies that benefit women when they feel the pressure from their female constituents – that is, when representatives are held accountable to those they purportedly represent. We follow Goetz et al. (Reference Goetz, Cueva-Beteta, Eddon, Sandler, Doraid, Anwar, Bhandarkar and Dayal2008: p. 2) and understand accountability as involving “assessment of the adequacy of performance, and the imposition of a corrective action or remedy in cases of performance failure.”

Such a conceptualization is perhaps most easily understood in the context of a democracy, where citizens-as-voters assess the adequacy of their elected politicians’ performance and then act to correct performance failure by voting them out of office. However, citizens can still impose meaningful corrective actions even when politicians are not elected through free and fair elections by taking various civic actions (Lindberg, Reference Lindberg2013). In addition, civil society and media actors play an equally if not more important role in many settings. Through what has been termed “diagonal accountability,” such actors may constrain governments indirectly by enhancing the effectiveness of other accountability actors (political parties, judicial branches, supreme audit institutions, etc.), or directly by pressurizing them through media or advocacy campaigns (Goetz and Jenkins, Reference Goetz and Jenkins2005; Mechkova et al., Reference Mechkova, Lührmann and Lindberg2019). Indeed, the presence and actions of women’s groups have been shown to play an important role when it comes to the enactment of policies advancing women’s priorities (Htun and Weldon, Reference Htun and Weldon2010; Shiffman and Smith, Reference Shiffman and Smith2007). Relatedly, Dovi (Reference Dovi2002) posits that descriptive representation will confer greater benefits when formal and informal interactions exist between representatives and those being represented.

In many settings, we expect that female citizens – and the diagonal accountability actors who represent their interests – will be more likely to hold female politicians to account. This relates to Pitkin’s notion of symbolic representation, which implies shifts in attitudes and habits. Having more women in positions of political power can break down widely held perceptions that politics is a man’s game, which in turn can improve women’s awareness and participation.

Formal representation and institutional rules

We also expect that formal representation will condition the nature and degree of answerability and sanctions when it comes to achieving gendered accountability. In particular, we expect the following rules and procedures (institutions) to matter: gender quotas, type of electoral system, and democracy.

Quotas have been argued to create a “mandate effect,” obligating female legislators elected under such institutions to act on behalf of women (Franceschet and Piscopo, Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008). Furthermore, by ensuring that a non-negligible number of women are present in the legislature, quotas can improve the likelihood that the interests of “women-as-group and women-as-differentiated-individuals” will be represented (Franceschet and Piscopo, Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008: p. 396). The importance of “critical mass” has been embraced by influential international institutions such as the United Nations (UN Women, 2020) though scholars caution against the notion of a “tipping point” at which change automatically occurs (Childs and Krook, Reference Childs and Krook2009). That said, we may still expect that legislatures featuring greater proportions of women should on average promote outcomes more favorable to them, following a logic similar to that outlined in Section 2.1. Indeed Clayton and Zetterberg (Reference Clayton and Zetterberg2018) find that when quota adoption results in a substantial increase in the number of women in parliament, countries see a shift in government priorities – increasing health budgets at the expense of military spending. Similarly, Swiss et al. (Reference Swiss, Fallon and Burgos2012) find that countries where women make up 20% or more of the legislature are more likely to experience improvements in child health.

Previous research has also shown that electoral systems with some degree of proportionality elect more women to parliament (Matland and Studlar, Reference Matland and Studlar1996). Whereas in majoritarian systems, parties can only nominate one candidate per district, making female candidates compete against existing interests within a party that may be dominated by men, proportional systems allow more flexibility to nominate women (Matland, Reference Matland1998). These systems also provide less of an advantage to incumbents, reducing the barriers to entry for female politicians (Thames and Williams, Reference Thames and Williams2010). Proportionality should matter for substantive outcomes as well, since such systems tend to generate higher levels of policy congruence between voters and governments and promote policy responsiveness (Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler, Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler2005; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Pierce, Thomassen, Herrera, Esaisson, Holmberg and Wessels1999; Stokes, Reference Stokes2001; Powell, Reference Powell2000).

Finally, democracies have more channels through which citizens can pressure their political representatives. As suffrage expands and poorer people are allowed voting rights, the preferences of the median voter shift toward introducing higher taxes and redistribution (Acemoglu and Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2005; Besley and Kudamatsu, Reference Besley and Kudamatsu2006). This shift in preferences incentivises governments to provide public goods to a larger pool of people or else they face the possibility of not being re-elected (Olson, Reference Olson2000). Furthermore, in democracies, state officials are more likely to be selected based on meritocratic reasons (Besley and Kudamatsu, Reference Besley and Kudamatsu2006). This in turn makes it more likely that qualified and impartial officials will implement the designed policies by the government. Empirically, the literature has found a strong relationship between democracy and development (Gerring et al., Reference Gerring, Thacker and Alfaro2012; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Mechkova and Andersson2018), with competitive elections as the main mechanism. Thus, extending the argument made above, we expect that in democracies women parliamentarians will also be more likely to implement policies in the interest of their (female) constituents. Footnote 2

Gendered accountability in Africa

Our theoretical framework is informed primarily by studies of Western Europe and the United States. However, sub-Saharan Africa is characterized by a distinct political history and institutions. That said, there are reasons to believe that certain assumptions are potentially more credible in the African context than in settings with more institutionalized politics. Our theory currently has no role for political parties, which can be important when it comes to selecting women to run for political office and supporting their successful campaigns (Kunovich and Paxton, Reference Kunovich and Paxton2005; Cowell-Meyers, Reference Cowell-Meyers2016). However, political parties in Africa tend to be less important when it comes to aggregating societal interests and serving as a vehicle for candidates to advance those interests. Rather, African parties frequently represent particular ethnic identities or personal interests (Elischer, Reference Elischer2013). Footnote 3 This grants representatives in most African political systems considerably more autonomy than their counterparts in more consolidated party systems. As noted above, it is precisely this autonomy that makes representatives’ personal characteristics (e.g., gender) important when it comes to promoting policies that serve the interests of their constituents.

Furthermore, non-electoral forms of political participation are particularly important in many African countries, where elections often fail to serve as a source of accountability due to a lack of programmatic parties and open and informed public debate (Joshi and Houtzager, Reference Joshi and Houtzager2012). Rather, what often matters more in such contexts is the extent to which civil society and media actors constrain government, either by enhancing the efforts of other accountability actors or by exerting direct pressure (Goetz and Jenkins, Reference Goetz and Jenkins2005; Mechkova et al., Reference Mechkova, Lührmann and Lindberg2018).

Moreover, gender roles in many African societies are highly circumscribed. For example, Kes and Swaminathan (Reference Kes, Swaminathan, Blackden and Wodon2006) analyze time-use surveys in Benin, South Africa, Madagascar, Mauritius, and Ghana and find that women devote substantially more time to care and domestic activities than men and considerably less time to market activities.

Empirical strategy and data

We systematically analyze variation in the extent to which women’s policy priorities are implemented through a series of cross-national, time-series regressions. We first consider how descriptive representation, operationalized as the proportion of women in the legislature, relates to the achievement of two policy outcomes that we argue disproportionately matter to women in the context we study: infant and child mortality. To provide a more convincing account that these outcomes shift partly in response to the actions of female legislators, we also analyze the composition of the budget in all countries and periods for which such data are available. Specifically, we look at the share of public resources for health.

Second, we investigate the conditions under which the descriptive-substantive representation link holds – specifically, whether it is enhanced when women participate in civil society and the media, which we argue is an important channel through which female citizens can hold female representatives to account. Finally, we examine how gendered accountability is conditioned by gender quotas, type of electoral system, and the extent to which a country is democratic.

The following sections describe the data and methods we use to measure our outcome variables, main explanatory variables, and potential confounding variables. Table A1 in the Appendix presents descriptive statistics for all variables, along with coverage, and data sources.

Dependent variables

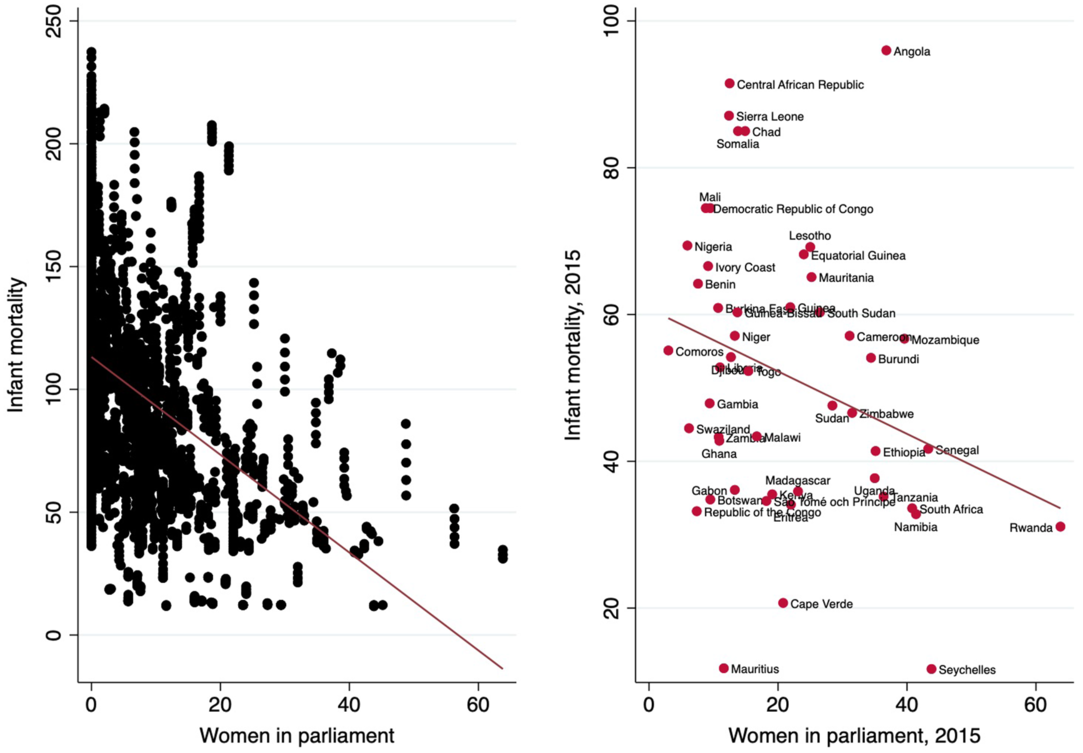

Our analysis focuses on the outcomes of two policy areas that we argue women disproportionately prioritize in our study setting: infant and child mortality. Footnote 4 We use data for infant mortality from Gapminder, spanning 1950 until 2015, and for child mortality from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators, available from 1960 to 2014. Instances of infant and child deaths have been substantially reduced in recent years. However, progress has varied. The lowest rate of infant mortality observed in our data is 11.7 deaths per 1,000 cases in the Seychelles in 2015, and the highest for that year is 96 per 1,000 cases in Angola.

Main explanatory variable: descriptive representation

We operationalize descriptive representation as the percentage of women in parliament, for which data are available from 1900 to 2017 from the V-Dem data set. Rwanda leads the region with a 63.8% of women in parliament in 2015. At the other end, the share of women in Comoros’s parliament was 3% in 2015. As an alternative measure of women’s descriptive representation, we also examine the proportion of women in ministerial-level positions.

Women’s participation

To measure women’s participation, we use V-Dem’s Women civil society participation index, which captures three related aspects: the extent to which women are free to openly discuss political issues, can form and participate in civil society organizations, and are represented in the ranks of journalists (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Lührmann, Marquardt, McMann, Paxton, Pemstein, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Wilson, Cornell, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Ilchenko, Krusell, Maxwell, Mechkova, Medzihorsky, Pernes, von Römer, Stepanova, Sundström, Tzelgov, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2019a, Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Lührmann, Marquardt, McMann, Paxton, Pemstein, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Cornell, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Mechkov, von Römer, Sundtröm, Tzelgov, Uberti, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2019b; Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Marquardt, Tzelgov, Wang, Medzihorsky, Krusell, Miri and von Römer2019).

Institutional rules and procedures

Our theoretical framework also anticipates that certain institutional conditions should affect the realization of gendered accountability. Specifically, we consider the existence of gender quotas and whether there is a mechanism to enforce these in practice. We also examine how our results vary given the type of electoral system that a country has in place. Finally, we test whether the influence of having more women in parliament depends on the country being a democracy. To capture how democratic a country is, we use a measure of how free and fair elections are. Footnote 5

Endogeneity and other potential determinants

Due to the nature of the data, it is difficult to disentangle causality in the relationship we are studying. We follow best practices from previous research to address the two main endogeneity concerns: reversed causality and omitted variable bias.

Reversed causality could be an issue in our analysis to the extent that high infant and child mortality rates could drive voters to choose female candidates in elections, as citizens might believe that female candidates are in better position to address such issues. To mitigate that, our main models use 5-year lags of the independent variables. This lag structure corresponds to the election cycle in many countries and also reflects the fact that our outcome variables are likely to change slowly as the implementation of any policy is time consuming. We also estimate system-GMM models with 5-year average panels, which are designed to address endogeneity concerns and to analyze relationships with slow-changing variables. Footnote 6

We expect variation in progress toward achieving women’s policy priorities to reflect a number of other country-specific factors. We estimate models with women in cabinet and gender quotas as main explanatory variables to rule out the possibility that changes in women’s standing in society are driving the results. We also include in our models several variables which could potentially influence both the dependent and independent variables. The rationale for including these variables is presented below, and the operationalization is provided in the Appendix.

Potential confounders

Foreign aid

Foreign aid to maternal, newborn, and child health accounts for a substantial proportion of overall public spending in many developing countries, including in sub-Saharan Africa (Requejo et al., Reference Requejo, Victora and Bryce2015). The presence of donors and international aid can also shift norms about gender equality in public office (Arriola and Johnson, Reference Arriola and Johnson2014).

Democracy

As noted above, previous research has shown that democracies are superior to non-democratic regimes in providing public health (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Mechkova and Andersson2018), and at the same time, the number of women elected in positions of power is higher in democracies (Kang and Kim, Reference Kang and Kim2018). Thus, in all models, we account for how free and fair elections are in a country, in addition to examining the conditional effects of democracy.

Economic development

More affluent countries tend to devote a greater share of resources to health (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Saksena and Holly2011). Countries with better supported health systems also tend to have a stronger human capital base and thus are more successful economically and might be more likely to elect women to power.

Corruption

Previous research has also pointed out that good governance determines social well-being (Rothstein, Reference Rothstein2011) since corruption and abuse of power can weaken politicians’ incentives to improve population health and lead to the under provision of public goods (Diamond, Reference Diamond2007). At the same time, rampant corruption can restrict women’s access to political parties, public sector jobs, and male-dominated clientelistic networks (Stockemer, Reference Stockemer2011).

Norms

In order to account for shifts in global social norms of the type that have led to the adoption of quotas (and potentially influence our dependent variables), we follow Kang and Kim (Reference Kang and Kim2018) and consider the year 1995 as a milestone date, when the Fourth World Conference on Women was held in Beijing, China. This conference resulted in a major declaration calling for the inclusion of women in public life at all levels. Similarly, we account for before and after the year 2000, when the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were adopted. The MDGs played a key role in promoting the reduction of maternal and child mortality.

Conflict

The presence of international or domestic conflict is another factor that affects socioeconomic outcomes, due to deaths as a result of the conflict or destruction of critical infrastructure. Further, Hughes and Tripp (Reference Hughes and Tripp2015) show that the end of long-standing armed conflict has substantial positive impacts on women’s political representation in sub-Saharan Africa, partially because men are more likely to die in battle.

We also estimate parsimonious models to mitigate posttreatment bias from including some of these controls. For instance, foreign aid is partly endogenous to institutions and politics more broadly and potentially to female representation more specifically. There are also studies suggesting that female politicians engage less in corrupt activities, so corruption may also be partially posttreatment.

Results

Figure 1 presents scatterplots with our main dependent and independent variables, showing at first glance the expected relationship between our main variables of interest. That is, countries with higher levels of women in parliament tend to have lower infant mortality both when looking at the full sample (left panel) and for just one point in time in year 2015 (right panel).

Figure 1. Scatterplot between main dependent and independent variables.

In order to interrogate this relationship more rigorously, Table 1 depicts the results of regression analysis based on an ordinary least square estimator, which specifies an additive linear relationship. We first present the models for infant mortality – Models 1 and 2, followed by Models 3 and 4, which focus on child mortality. The first set of models for each dependent variable includes a lagged dependent variable on the right-hand side to account for dynamic effects and autocorrelation in the residuals (Keele and Kelly, Reference Keele and Kelly2005), Footnote 7 as well as panel-corrected standard errors (Beck and Katz, Reference Beck and Katz1995). A lagged dependent variable also models that the current values of the dependent variable depend on its past realizations, this also helps to control for any potential omitted variable affecting past outcomes. In this set of models, the independent variables are lagged by five years. Footnote 8

Table 1. Regression results with share of women in parliament as main explanatory variable

Standard errors, clustered by country, in parentheses.

* p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Models for infant mortality based on years 1958–2015; child mortality – 1969–2015.

The second specification – Models 2 and 4, respectively – include country and year-fixed effects, which account for stable country factors as well as global trends in the evolution of both women’s political representation and the various development policy outcomes. We also include as a control variable the average of the dependent variable in sub-Saharan Africa which takes into account regional characteristics such as disease epidemics or the introduction of medical treatments specific to the region and time.

Table 1 depicts a significant negative association between descriptive representation and infant mortality. That is, a greater proportion of women in parliament is associated with lower numbers of infant deaths, accounting for past values of the dependent variable and important covariates such as aid, democracy, corruption, urbanization, and wealth. This statistically significant result also holds in the second, stricter specification of the model with two-way fixed effects. This suggests that the the influence of women’s representation on infant mortality is independent from time trends that could affect both development and women’s representation (such as global norm changes or major historical events) and slowly changing country-specific characteristics (such as geography or social norms). The results are robust when we use child mortality as dependent variable (Models 3 and 4), both when estimating panel-corrected standard error and fixed effects regressions.

To illustrate the substantive size of the effects, Figure 2 shows the predicted values for infant mortality with uncertainty estimates around them, as calculated by the dynamic model in Table 1, for two scenarios: when the percentage of women in parliament is 0 (blue dots) and when the share is 60 (historically, maximum value for Africa, shown in red squares), while all other variables are held at their mean. The figure shows that historic declines in infant mortality are accelerated when women are well represented in parliament. When transformed back to the original values, mortality rates at time period ten when there are no women in parliament are estimated to be around 75 deaths per 1,000 (Ivory Coast in 2011), and around 55 deaths (Ghana in 2007) when women in parliament are at their maximum value.

Figure 2. Predicted values of infant mortality by levels of women in parliament.

Finally, the results for the control variables mostly go in line with existing research and theoretical expectations. Stronger democratic institutions and lower levels of corruption tend to be associated with improved outcomes. Foreign aid, urban population, and GDP per capita show less consistent results as predictors of the dependent variables.

Resource mobilization for women’s policy priorities

Progress toward the outcomes we study can require both policy changes and shifting public spending priorities. In order to reduce infant mortality in sub-Saharan Africa, governments need to spend considerable resources on programs such as malaria control, immunizations, and reproductive healthcare. Given our hypothesis that women will prioritize such health-related outcomes, the composition of the budget in legislatures featuring large numbers of women should be characterized by an increased share of public resources for health.

Model 1 in Table A7 in the Appendix depicts the results of regression analysis with the percentage of public health expenditures (as share of GDP per capita) as main outcome variable. The results suggest that having more women in parliament is positively associated with greater public expenditures for health (2.5 percentage points on average). In addition, we estimate a model where military expenditure is the dependent variable (Model 2). This model serves as placebo test – we would not expect the number of women in parliament to have a significant association with military expenditure, and indeed we find that the association with military expenditure is negative.

Impact of women’s participation

According to our gendered accountability framework, the influence of women in the legislature will be enhanced when female citizens are taking action to hold their representatives to account. Such actions may be direct or take place through civil society organizations and the media. We therefore estimate an interaction effect between descriptive representation and the degree of female participation. Model 1 in Table A8 in the Appendix presents our regression estimates. We find a statistically significant interaction between women’s participation and the share of women in parliament when it comes to reducing infant mortality.

Figure 3 depicts the effects from our regression analysis. On the left-hand side of the figure, we present the conditional effect of women in parliament on infant mortality at different levels of women’s participation. The negative effect on infant mortality of having more women in parliament is stronger for countries with higher participation of women in civil society and media. The effect becomes significant around 0.4 on this 0-to-1 measure, or contexts in which the space for civil society and media is not completely restricted.

Figure 3. Interaction of share of women in legislature and women’s civil society participation (DV = Infant Mortality).

The right-hand panel shows that the effect of women’s participation on infant mortality becomes statistically significantly only after the proportion of women in parliament reaches a certain level (around the mean values). Footnote 9 This adds nuance to evidence in favor of critical mass theories.

Gendered accountability and formal representation

Our theoretical framework also anticipates that the rules and procedures to select representatives are important conditions affecting the realization of gendered accountability. Table A9 in the Appendix summarizes the findings from the regression analysis of interaction terms between share of women in parliament and the type of electoral system, existence of quotas, and extent of democracy.

Figure 4 shows the relationship between infant mortality and the interaction between the share of women in parliament and two institutions of formal representation. In Figure 4a, we compare the influence of having more women in parliament on mortality rates when the electoral system is majoritarian (shown in solid black line) and when there is some proportional element (red dashed line). In Figure 4b, we see the effect for countries with electoral quotas (orange dashed line) and for countries without quotas (purple solid line). In both cases, the results go in line with our theoretical expectations: there is a strong negative effect on mortality in countries with proportional or mixed electoral systems and for those that have adopted quotas.

Figure 4. The effect on infant mortality of the interaction between share of women in parliament (logged) and formal representation.

The results are less clear when we consider the degree of democracy. Figure 5 shows that countries with free and fair elections (green dashed line) tend to have lower infant mortality rates than in countries without elections or with highly restricted elections (blue solid line). Note also that the interaction term in the regression analysis is not statistically significant. However, this null finding of interaction effect is inconclusive and should be tested more thoroughly with larger samples, especially given the limited number of democracies in our sample. Footnote 10

Figure 5. Interaction of share of women in legislature (logged) and free and fair elections (DV = Infant Mortality).

Robustness checks

In the following three subsections, we test the robustness of our findings both by employing other estimation strategies and by performing placebo tests. We use several strategies to account for what we see as the main source of potential omitted variable bias – the fact that the general standing of women in societies could lead to improved results both in our dependent and independent variables.

Alternative model specifications

The literature on panel data analysis does not give a clear answer to the question of which models best fit the complex two-dimensional data structure of countries over time. Since we do not know what the true data generating process is for these variables, we compare the results from different models for the dependent variable of interest. Table A2 in the Appendix shows six alternative estimations of the main models presented in the previous section, including a parsimonious model to avoid posttreatment bias; different lag structures of the independent variables and the regional average of the dependent variable; a model using system-GMM estimator, which is appropriate in cases where the dependent variable is slow changing, and affected by its own past values; tests for stationarity of the data. According to these models, the share of women in parliament remains a significant predictor of infant mortality at the statistical significance at level 0.01 or 0.1 no matter the model specification.

Another challenge to our empirical analysis is that there are many country-years for which there are no women in parliament. To explore this, we reestimate the main regression by transforming the main independent variable into a binary one – where 0 corresponds to no women in parliament and 1 to having one or more female legislators. Table A3 in the Appendix shows that the coefficients for this binary variable are not statistically significant on their own (Model 1), and the significant results hold for the continuous variable when we control for the presence of women (Model 2). This finding goes in line with evidence from previous studies that for the presence of women to matter in substantive terms, the number of women is important and introducing just a small share of seats for women might not make a difference (Dahlerup, Reference Dahlerup2006; Grey, Reference Grey2006).

Placebo test

To further interrogate our results, we also test whether greater presence of women in parliament is associated with another key development outcome – electrification, proxied with night-light data. In this way, we aim to test the notion that all good things go together or that all developmental aspects improve. We choose electrification as a placebo since our theory would not predict an association between more women in parliament and improved infrastructure, given that the latter is a development outcome that men are more likely to prioritize (Gottlieb et al., Reference Gottlieb, Grossman and Robinson2016).

This test also allows us to discount an alternative mechanism for the association between female representation and improvement in policy areas that matter to women – that women are in general more trustworthy and public spirited than men and should be more effective in reducing corruption (Dollar et al., Reference Dollar, Fisman and Gatti2001). Given that corruption has been found to be associated with the under provision of public goods, this could represent an alternative channel through which women could promote improved service delivery. If this channel is operating, then we should expect to see improved outcomes across all types of public goods – not only those that women prioritize.

Appendix Table A4 depicts the results of our placebo test. We do not see a significant association between the share of women in parliament and electrification, giving us greater confidence that the preceding empirical results serve to corroborate our theory.

General trends in female empowerment

Finally, an outstanding concern is that some latent trend in society might be causing general improvement of the status of women, which would be reflected in the number of women in parliament. At the same time, this trend might be causing other improvements in gender equality. To address this concern, we estimate models with proxies for the general standing of women in politics and society and also control for major events in recent history to account for changing norms over time.

First, Table A6 shows that the share of women in cabinet is not a significant predictor of infant deaths. We interpret this as support for the fact that women in parliament, and not just a higher number of women in politics is associated with improvements in development. Further, these result strengthen the accountability framework we posit. In many African countries, incumbents use ministerial positions primarily as patronage appointments. This can lead fewer women to be appointed to cabinets in the first place (Arriola and Johnson, Reference Arriola and Johnson2014) and also means that they have less of a mandate to represent the interests of women broadly speaking. Women are frequently allocated “soft” or “feminine” cabinet assignments, which may also be rooted in efforts to marginalize women (Krook and O’Brien, Reference Krook and O’Brien2012). As such, we may expect women in such positions to lack the ability to implement their priorities. Moreover, the fact that cabinet positions are appointed rather than directly elected limits the motivation and ability of (female) citizens to hold their (female) ministers to account.

Additionally, Model 4 in Table A5 includes a dummy variable for whether a country has gender quotas, which we can also interpret as a proxy for the general improvement of the role of women in a society. Our results remain stable to this specification.

Finally, we estimate models with several other factors that might affect our outcome and explanatory variables at the same time – namely, the introduction of the MDGs and the 1995 Beijing conference on women. The results for Models 1 and 2 in Table A5 in the Appendix remain largely unchanged with a statistically significant relationship for infant mortality. Finally, we control for international and internal armed conflict, as shown in the same table.

Discussion

Our analysis shows that increasing descriptive representation can have meaningful implications for the realization of policy goals that matter to women, in democracies and autocracies alike, particularly when female citizens are politically aware and engaged. These findings are highly policy-relevant given that all of the outcomes we study correspond to internationally agreed upon development targets. This is important since many countries, particularly in Africa, did not meet the reductions in infant and maternal mortality targeted in the MDGs. Our results are also important in light of the fact that little research has been done to investigate the implications of having women represented in politics on people’s everyday lives.

We also contribute by delineating societal and institutional conditions under which female politicians will be more inclined to take action to further the interests of female voters. First, we show that the influence of women in parliament is strengthened in countries where women participate relatively more in civil society. This can put increased pressure on female representatives to act in female citizens’ interest. These quantitative results go in line with qualitative evidence from the countries in our sample. For instance, in post-genocide Rwanda, prior to the adoption of gender quotas, women civil society organizations joined forces with the few women MPs in the transitional national assembly to lobby for changes to exclusionary inheritance laws. In addition, women’s organizations played an important role in that country to successfully lobby for the adoption of gender quotas (Bauer and Burnet, Reference Bauer and Burnet2013). In Uganda, the strength of women’s organizations and the relationships between civil society actors and pro-women MPs are seen as essential for the successful advancement of legislation benefiting women (Wang, Reference Wang2013).

Furthermore, we show that efforts at the institutional level matter for policy outcomes, in particular, we demonstrate the importance of gender quotas and proportional representation to strengthen the link between descriptive and substantive representation. Therefore, while there may be systematic differences between women who entered parliament as part of the quota system and women who were elected freely (Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, Josefsson and Wang2014), our analysis shows that institutional efforts to improve women’s representation can have a meaningful impact.

It is also important to note that our empirical results may represent an underestimate of this impact. In many cases, descriptive representation may lead to substantive representation in more process-oriented terms, such as introducing and/or supporting bills that address women’s issues, networking with female constituents or women’s organizations, or advancing women’s issues within committees or party delegations (Franceschet and Piscopo, Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008). However, there are a number of examples of other process-oriented developments in the context we study. For example, in Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda, cross-party coalitions of female Parliamentarians have formed as women have increased their presence in the national legislature and have played an important role to coordinate the development of shared legislative agendas (Devlin and Elgie, Reference Devlin and Elgie2008; Johnson and Josefsson, Reference Johnson and Josefsson2016; Yoon, Reference Yoon2011). Our findings for increased health budgets are a step in that direction.

While such process-oriented developments are necessary for laws and policies to be enacted that ultimately influence the outcomes we study, they are no guarantee that such outcomes will be realized. The gap between policy and implementation is an oft-cited challenge across sectors in many African countries. Such gaps can stem from a given policy outcome not being perceived as a public problem, failures to seize existing windows of opportunity, and a lack of policy entrepreneurs (Ridde, Reference Ridde2009). Further research is needed to better understand the constraints that female politicians confront when it comes to effective advocacy on behalf of their female constituents. One issue may be the nature of women representatives’ contributions to parliamentary debates (Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, Josefsson and Wang2014). To understand additional constraints, ethnographic work along the lines of Bauer and Burnet’s (Reference Bauer and Burnet2013) study of female MPs in Rwanda would be enlightening. Systematic surveys of politicians in the African context that allow for meaningful comparison across gender would also add to our knowledge base. Given that descriptive representation of women in Africa is now on par with the global average, it is high time that we gain a better understanding of the experiences and challenges these legislators face.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773920000272.