Introduction

“COVID-19 will reshape our world. We don’t yet know when the crisis will end. But we can be sure that by the time it does, our world will look different.” These were the words of the High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell, in March 2020.Footnote 1 Like Borrell, many international analysts and scholars saw the COVID-19 crisis as a source of power shifts in the international order. Francis Fukuyama, for example, compared the potential effects of the pandemic to those of other major crises – such as the Great Depression, World War II, the 9/11 attacks, and the 2008 financial crisis – that have transformed international politics and called for researchers to predict the effects of the pandemic (Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama2020, 7).

While global crises demand international cooperation to contain them, they also provide opportunities for states, particularly world powers, to pursue their own foreign policy goals and national interests (Fazal Reference Fazal2020). The crisis choked off global supply chains and generated production bottlenecks that affected the availability of crucial medical supplies, from masks to ventilators. In the face of these shortages, publicly displaying generosity and goodwill and providing material assistance to those who needed it the most emerged as a strong tool of public diplomacy, soft power, and foreign aid delivery. This became apparent in the early days of the crisis, with China providing emergency goods and medical supplies worldwide and promoting the message that, unlike the United States of America (USA), it was a reliable leader in the global response to the pandemic.

Do global crises create an opening for public diplomacy to make a difference in international politics? Can they constitute an opportunity for world powers to improve their international standing? Can public diplomacy contribute to some of the major changes analysts and scholars foresaw in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis? In this article, we tackle these questions. As public perceptions are important for the transformational impact of crises (Lipscy Reference Lipscy2020), we focus on citizens’ attitudes towards world powers. We explore whether, in the context of a USA–China race for regional and international global leadership (Broz, Zhang, and Wang Reference Broz, Zhang and Wang2020; Shambaugh Reference Shambaugh2018), public diplomacy can shape the importance that individuals attach to whether a world power is a democracy or not when forming their attitudes towards world powers.

To do so, we fielded a survey experiment in Italy, the central battleground of what came to be known as “mask diplomacy” in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. We randomly presented participants with “positive” and “negative” information cues about public diplomacy efforts by the USA and China and then asked them how important it was for them that Italy privileged international relations with democratic regimes.

Our findings indicate that public diplomacy can shape peoples’ attitudes towards international politics, at least during major crises and in the short run. Our participants reasserted the importance of privileging international relations with democracies when they were told that a democracy (the USA) effectively assisted Italy in facing the emergency. At the same time, they discounted the importance attached to international allies being democracies when they were presented with positive information about actions carried out by a non-democracy (China). These effects depend on the participants’ support for democracy at home: the effect of the China-positive cue was strongest among those who strongly supported democracy at home. Negative cues stressing insufficient assistance did not sway attitudes, regardless of whether the country was a democracy (USA) or a non-democracy (China). While our vignettes make reference to concrete countries (the USA and China), we offer evidence that the effects we observe are not picking up changes in attitudes towards these specific countries but on whether people think that international allies should be democracies.

As in other Western European countries, most Italians have consistently considered democracy the best form of government, reported more positive evaluations of the USA than of China, and have long preferred the USA as an international ally.Footnote 2 Until Spring 2020, when COVID-19 hit Italy hard, most Italians considered the USA the economic leader in world politics and saw China as a major threat. This makes Italy a hard case for a light-touch intervention to sway public attitudes. Yet, against this backdrop, we argue that a cognitive dissonance framework, where people update their attitudes to decrease dissonant cognitions when they receive information that challenges prior beliefs or expectations, helps explain our findings.

Our article makes three key contributions to current International Relations and Foreign Policy debates. First, by offering empirical evidence of how cues about acts of public diplomacy in times of crisis can shape peoples’ attitudes towards international actors and allies (Weitsman Reference Weitsman2010, Reference Weitsman2013), it furthers a growing literature that moves beyond theoretical treatments of public diplomacy to empirically assess its effectiveness. In doing so, it contributes to research on aid as a foreign policy and soft power tool, which has stressed the importance of exploring the effects of aid not only on recipient governments but also on the attitudes of recipient populations (Blair, Marty, and Roessler Reference Blair, Marty and Roessler2022). Our findings add to recent efforts to evaluate the effect of public diplomacy by non-democracies in the Western hemisphere and among countries traditionally allied with the USA (Hackenesch and Bader Reference Hackenesch and Bader2020; Kurlantzick Reference Kurlantzick2007).

Second, by assessing the effects of public diplomacy in times of crisis, we contribute to debates on whether the COVID-19 pandemic mattered for international politics (Cooley and Nexon Reference Cooley and Nexon2020; Drezner Reference Drezner2020). Our results suggest that the crisis might have opened up opportunities for actors to stir changes in international outcomes, even if these changes fall short of an abrupt transformation in world politics. Finally, our article speaks to a major current debate in International Relations around the rise of China in international politics (Mastanduno Reference Mastanduno2019), the supposed hegemonic transition between China and the United States (Allan, Vucetic, and Hopf Reference Allan, Vucetic and Hopf2018; Brooks and Wohlforth Reference Brooks and Wohlforth2015; Weiss and Wallace Reference Weiss and Wallace2021), and the so-called crisis of the “Liberal International Order” (Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2018; Lake Reference Lake2020; Musgrave Reference Musgrave2019). We provide empirical evidence of the effects of China’s efforts to forge a more positive image of itself among Western societies (Chu Reference Chu2021; Eichenauer, Fuchs, and Brückner Reference Eichenauer, Fuchs and Brückner2021; Goldsmith and Horiuchi Reference Goldsmith and Horiuchi2009) and the USA’s efforts to avoid the decoupling of key allies from its hegemonic system (Lake Reference Lake2020). These insights are particularly relevant, as competition over soft power is one of the central areas where the race to global power is taking place.

What is public diplomacy?

Definitions of public diplomacy abound, yet most tend to converge on the same core attributes. We follow a growing consensus that public diplomacy is a tool of soft power, commonly (but not exclusively) performed by governments, targeted at a foreign public, with the aim of influencing attitudes on the formation and execution of foreign policy to support national interests and values abroad (Gregory Reference Gregory2011; Hartig Reference Hartig2016; Melissen Reference Melissen2005; Nye Reference Nye2008; Rugh Reference Rugh2011).Footnote 3 Hence, “public diplomacy is a form of self-presentation, by which states […] try to affect the attributions that significant others (in this case, foreign publics) make with respect to their identity” (Mor Reference Mor2007, 662).

While traditional diplomacy is about relationships between the representatives of states or other international actors, public diplomacy involves a distinct audience: the general public in foreign societies (Goldsmith, Horiuchi, and Matush Reference Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Matush2021). As such, it is a form of two-way communication, a process of dual dimensions at domestic and international levels, to develop and share a compelling narrative of national values. In sum, public diplomacy “listens to and builds on what people have to say” (Melissen Reference Melissen2005, 18).

Does public diplomacy matter?

While scholars substantially agree on conceiving public diplomacy as a tool to influence the public in foreign countries, less consensus emerges on its actual effectiveness. Efforts to assess whether public diplomacy enhances foreign audiences’ appraisals have recently increased. Yet, the empirical record of this literature, which has predominately focused on the USA as the “sender” and non-European audiences as the “receiver,” remains mixed. For example, in a cross-national study, Goldsmith, Horiuchi, and Wood (Reference Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood2014) found that USA aid targeted to address HIV/AIDS substantially improved perceptions of the country among receiving audiences. In contrast, Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters (Reference Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters2018), in an experimental study in Bangladesh, only found a limited positive effect of foreign aid on general perceptions of the United States and no significant effects on opinions on essential foreign policy issues. Similarly, focusing on Afghanistan, Böhnke and Zürcher (Reference Böhnke and Zürcher2013) found that aid did not improve Afghans’ perceptions of the donors.

Shifting from aid to another form of public diplomacy – high-level visits by national leaders to other countries – evidence is similarly mixed. In an early study, Goldsmith and Horiuchi (Reference Goldsmith and Horiuchi2009) showed that while US international visits after 9/11 had a positive effect initially, this effect weakened as the “war on terror” progressed and eventually exhibited a backlash. More recently, in a cross-national study exploring the effect of visits by leaders from 9 countries to 38 countries, Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Matush (Reference Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Matush2021) found an increase in public approval among foreign citizens, particularly when the media reported these activities well.

Given this mixed empirical record, further studies on the effects of public diplomacy on foreign public opinion are needed. Moreover, given the predominant focus on the USA and a few other non-Western democratic countries (Darnton Reference Darnton2020), little is known about whether the effectiveness of public diplomacy varies across democratic and non-democratic states. While it has been hypothesized that public diplomacy by non-democratic countries is less effective than that by democratic ones (Chu Reference Chu2021), the potential reception of the effectiveness of non-democracies’ efforts has been subjected to relatively limited empirical investigation. This is surprising not only in light of the current hegemonic race between the USA and China, but also given existing arguments that cultural and political proximity can enhance successful public diplomacy (Entman Reference Entman2008; Kohama, Inamasu, and Tago Reference Kohama, Inamasu and Tago2017).Footnote 4

A few recent studies have explored the effects of China’s foreign aid on non-European foreign publics and, here again, the limited evidence is mixed. For example, Blair, Marty and Roessler (Reference Blair, Marty and Roessler2022) find that Chinese aid to Africa does not increase – and might even reduce – beneficiaries’ support for China. Similarly, Eichenauer, Fuchs and Brückner (Reference Eichenauer, Fuchs and Brückner2021) do not find evidence that Beijing’s aid in Latin America affects average attitudes towards China – if anything, it contributes to more polarized opinions about China. In contrast, Mattingly and Sundquist (Reference Mattingly and Sundquist2022) find that, in India, Chinese public diplomacy can effectively improve citizens’ perceptions of China – yet, their study does not focus on the effect of aid directly but on (real) Tweets by Chinese diplomats emphasizing foreign aid generosity.

In sum, while empirical research on the effects of public diplomacy has recently grown, the empirical record remains mixed. Moreover, most of this work has focused on the USA as a “sender,” and little effort has been made to compare its effectiveness across democracies and non-democracies. Furthermore, perhaps because most of this research has focused on the effects of international development aid,Footnote 5 studies have explored effects on developing countries; we need yet to explore effectiveness among different types of “receivers,” such as the European public. Finally, despite the focus on foreign policy in public diplomacy, studies have rarely explored concretely whether it affects citizens’ attitudes towards international allies. Given world powers’ efforts to improve their international standing by offering support and leadership in the global response to the virus, the COVID-19 pandemic offers an opportunity to fill in some of these gaps by empirically assessing the impact of explicit public diplomacy efforts conducted by both democratic and undemocratic states.

The effectiveness of public diplomacy and regime type

What shapes the effectiveness of public diplomacy? Credibility of information, perceived legitimacy, political proximity, and value resonance have been identified as crucial for effective public diplomacy (Goldsmith and Horiuchi Reference Goldsmith and Horiuchi2009; Nye Reference Nye2008). In light of these factors, it has been argued that effectiveness is likely shaped by the “ideational congruence” between the identity of the “sender” and the “receiver” (Schatz and Levine Reference Schatz and Levine2010).Footnote 6 Consequently, a lack of congruence in regime type between the “sender” and the “receiver” is likely to constitute an “ideational barrier” to the effectiveness of public diplomacy (Allan, Vucetic, and Hopf Reference Allan, Vucetic and Hopf2018). While public diplomacy efforts by a democracy should have a strong positive impact on attitudes amongst a democratic public, efforts by non-democracies should not have such an effect.

The USA has long used public diplomacy in both democratic and non-democratic contexts. Yet, it is cognizant of the importance of “ideational congruence.” For example, Frensley and Michaud (Reference Frensley and Michaud2006), after scrutinizing the aims of public diplomacy set out in the 2002 US National Security Strategy,Footnote 7 emphasize that the document assumes that while mass audiences in democratic states “will naturally support U.S. foreign policy goals,” in authoritarian states they “will fail to support USA values, goals, and policies because they lack knowledge of democratic values”(2006, 203).

China has also recognized the importance of international image and soft power (Shambaugh Reference Shambaugh2018) and sees public diplomacy “as a means for telling China’s story to the world” (Hartig Reference Hartig2016, 1). However, while China’s public diplomacy seems to have certain favourable features – for example, a centralized coordination and economic success (d’Hooghe Reference d’Hooghe2011) – it has been argued that the lack of legitimacy of its political system in the eye of a Western democratic public has undermined its efforts to promote compelling public diplomacy. According to Chu (Reference Chu2021, 970), “scepticism of China appears to stem substantially from its domestic political ideology.” The author considers liberal democracy as a cleavage in world affairs, arguing that people from democratic communities “tend to see China as belonging to an out-group and thus evaluate its influence as being relatively negative” (Chu Reference Chu2021, 961).

Is it really the case that a Western democratic public will naturally well receive public diplomacy efforts by an international democratically? Similarly, should we expect Chinese public diplomacy to fail in European contexts due to the “enormous gap between European and Chinese ideas and values” (d’Hooghe Reference d’Hooghe2011)? Is being perceived as a democracy a necessary premise for a Western public to support the establishment of international alliances? Can things change during acute periods of crisis?

Empirical expectations: cognitive dissonance and dissonance reduction

If public diplomacy is about promoting positive images of one’s country abroad to alter public perceptions and attitudes, then an acute emergency can present a great chance for countries to exercise it by providing assistance to deal with that emergency. The COVID-19 pandemic was a case in point: it exceeded most countries’ ability to respond individually, raising the need for external assistance. In this critical context, international actors sought to improve their image and expand their influence through statements of support and by providing material aid in the form of health equipment (e.g. masks and ventilators) and/or health personnel. As such, following scholars like Goldsmith, Horiuchi, and Wood (Reference Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood2014) and Komiya, Miyagawa, Tago (Reference Komiya, Miyagawa and Tago2018), this study focuses on health aid as an instrument of public diplomacy, a relatively new domain of competition between world powers, in particular the US and China (Fazal Reference Fazal2020, 15).

In this context, we explore whether “positive” and “negative” information cues about public diplomacy efforts to provide assistance to deal with the health emergency shape public attitudes in the “receiving” public.Footnote 8 More specifically, we explore whether the identity of the “sender” – the USA, a democracy, or China, a non-democracy – affects the importance a Western and strongly pro-democratic public, Italian citizens, assigns to the fact that its country’s international allies are democratic.

We argue that information cues about the assistance offered by both democracies and non-democracies to deal with an emergency can change public attitudes – at least in the short run. However, the ideational congruence between the “sender” (state) and the “receiver” (citizen) is at the heart of how we expect these attitudinal changes to pan out. We assume that the behaviour that a citizen expects from a given state is based on ideational congruence: if I’m pro-democratic and uphold Western values, I’m more likely to expect assistance from another Western democracy (USA) than from a non-Western autocracy (China). Therefore, whether I update my attitudes in light of assistance received in times of crisis depends on whether or not this assistance runs counter to these expectations. Consequently, we anticipate attitudinal change when there is a possible relative dissonance between “the expected” and “the factual” (or information about the factual).

This argument is grounded on a classical framework elaborated in social psychology according to which peoples’ attitudes can change through a process of cognitive dissonance and subsequent dissonance reduction (Festinger Reference Festinger1962). Cognitive dissonance is defined as “a negative affective state characterized by discomfort, tension, and heightened physiological arousal” triggered when behaviour does not align or openly clashes with a person’s values or beliefs (McGrath Reference McGrath2017, 1). The fundamental premise of dissonance theory is that people on average experience a negative effect following the detection of cognitive conflict. Given that this effect is negative and unwanted, they will seek ways to extinguish or at least reduce this dissonance.

Among several strategies of dissonance reduction, the one that has received the most empirical backing (and attention) is changing one’s attitude to decrease the number of dissonant cognitions (McGrath Reference McGrath2017).Footnote 9 When individuals experience mental discomfort after observing behaviour or receiving information that is perceived to conflict with their starting beliefs or expectations, to diminish or evade this discomfort, they will try to update their attitudes to better align them with the information received. As Barry (Reference Barry1990, 5) notes, “the machinery of cognitive dissonance reduction comes into play to create a pressure towards bringing belief into line with performance.” Our expectations about the possible effects of our information cues are based on this widely used dissonance reduction strategy. In line with a wealth of experimental psychological research, we contend that the induction of dissonance is what creates reasons to change attitudes (Festinger Reference Festinger1962; McGrath Reference McGrath2017).

While cognitive dissonance arousal and reduction have been mainly developed in psychological research, insights from this literature have been used in various subfields of political science, most notably political communication and political choice (e.g. Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018). In International Relations, Jervis’ (Reference Jervis1976, 406) seminal work on how states perceive and misperceive themselves in international politics, also discussed, in detail, the causes and consequences of cognitive dissonance, stressing that “in constructing defensible postures to support their self-images, people must often rearrange their perceptions, evaluations, and opinions.” He was quite explicit about the dissonance reduction strategy we build on here to develop our hypothesis: “reducing dissonance can involve changing evaluations of alternatives, thus altering desires themselves” (Jervis Reference Jervis1976, 384). However, in our case, the dissonance is between individuals’ expectations about the actions of international actors and observed actions (or information about these actions), and the reduction strategy will aim at aligning these expectations with the information provided by changing attitudes. This is, ultimately, what public diplomacy aims to achieve: attitudinal change.

Following the logic described above, positive or negative cues about assistance to deal with the COVID crisis should affect attitudes as long as they run counter to peoples’ expectations. Hence, positive cues should affect average attitudes of a democratic public when the “sender” is an autocracy, like China, because it will create cognitive dissonance in the “receiver,” who would try to reduce it by updating their previous beliefs. By the same token, negative cues should affect attitudes amongst a democratic public if the “sender” is a democracy, like the USA. Our core expectations can be translated into testable hypotheses as follows:

HYPOTHESIS 1: China—Cognitive Dissonance – Positive information cues about China’s assistance reduce the importance the public attaches to establishing international relations with democratic regimes.

HYPOTHESIS 2: China—Expected Behaviour – Negative information cues about China’s assistance do not affect the importance the public attaches to establishing international relations with democratic regimes.

HYPOTHESIS 3: USA—Expected Behaviour – Positive information cues about the USA’s assistance do not affect the importance the public attaches to establishing international relations with democratic regimes.

HYPOTHESIS 4: USA—Cognitive Dissonance – Negative information cues about the USA’s assistance reduce the importance the public attaches to establishing international relations with democratic regimes.

Research design

Between July 3 and July 9, 2020, we conducted a survey experiment in Italy to explore different dimensions of the impact of COVID-19 on attitudes towards international politics. Our sample consisted of 2,100 participants recruited (via an invitation) from an online panel held by the survey firm CSA Research. The sample mirrored the national distribution of the Italian voting-age (18 and above) population in age, gender, education, socio-economic status, and region of residence. The questionnaire, administered online, included 30 questions in total and took participants seven minutes on average to complete.Footnote 10 Participants in the survey were randomly assigned to seven experimental conditions. For the concrete research question addressed in this paper, we focused on five of these experimental conditions and thus, depending on the models’ specifications, we worked with a sample of between 1,100 and 1,500 participants.Footnote 11

Why Italy?

Italy constitutes an appropriate case for exploring the potential effects of public diplomacy on Western European countries. Italy was the first Western country to be hit by COVID-19. When the virus became a national emergency in late-February 2020 and Italy found itself in desperate need of assistance, COVID-19 was already largely under control in China, and it was not yet a problem – at least not an acknowledged one – in the USA. As such, in less than a month, Italy became a laboratory for superpowers’ public diplomacy. In fact, great powers proved hyper-reactive in terms of public initiatives. By mid-March, the Italian public were aware of China’s help, in the form of medical equipment and expertise. Even if public and health diplomacy by the USA appeared to be minimal during COVID-19, relative to past pandemicsFootnote 12 , its response to China’s actions in Italy was blunt. In early April, Mike Pompeo, then Secretary of State, explicitly reassured the Italian public that the USA was there to assist the country: “There is no country in the world that will provide as much aid and assistance through multiple forms as the United States of America will.”Footnote 13 This makes Italy not only an appropriate case for fielding our study, but a particularly significant one within the European context.

At the same time, pre-COVID trends in Italian public opinion towards great powers make Italy a particularly interesting case for our hypotheses. First, as available survey data reveal, a large majority of Italians see democracy as the best form of government and consider it of prime importance to be living under this type of regime. In fact, comparative data from the European Social Survey (2012) and the European Values Study (2017) shows that the percentage of Italians who consider living under a democratic government as “extremely important” is one of the highest (57.9% in European Social Survey) in the continent, shortly behind Germany (60.6%) and Scandinavian countries, and well above other countries, such as France, Spain and the UK (45.5%). Second, over the past decade Italians have consistently reported a preference for the USA over China as an international ally. This contrasts with preferences in other leading European countries, such as France and Germany, where during the same period public opinion has fluctuated much more (Pew Research Center 2020). Similarly, up until the COVID-19 crisis, while public opinion in other European countries had increasingly begun to recognize Chinese economic dominance, Italians consistently considered the USA as the world’s economic leader (Global Attitudes Survey data). Third, at substantially higher rates than other EU counterparts, such as Germany, Spain and Greece, Italians perceive Beijing as a major threat and report a sense of economic vulnerability vis-à-vis China (Dennison Reference Dennison2019).Using data collected between 2006 and 2014, Chu (Reference Chu2021) showed that Italy, among liberal-democratic countries, is the one with the most negative opinion of the overall impact of China on world affairs.Footnote 14

The strength and stability of Italian attitudes towards world powers speaks against our overarching expectation that public diplomacy efforts in times of crisis may sway public attitudes towards China and the USA. Furthermore, pro-democracy, pro-USA, and anti-China attitudes prevalent in pre-COVID times make it hard for Italians to react to positive cues about China’s support by discounting the importance they attach to Italy privileging international relations with democratic regimes. As such, if we are to observe a shift in attitudes among the Italian public, we could expect similar, if not stronger, effects in other countries, where preferences have not been as stable, and where the public are not so pro-USA and anti-China in their perspectives. Moreover, the COVID-19 health emergency might also prove to be an inflection point regarding political attitudes.

Experimental manipulations

After a set of pre-treatment questions relating to socio-demographics and tapping into political preferences, political knowledge, and exposure to COVID-19, participants were randomly assigned to one of five experimental groups. In the control group (Group 1), participants read a short vignette briefly describing the COVID-19 emergency faced by Italy during the spring of 2020, mentioning the shortage of medical supplies and personnel. Participants in Groups 2 through to 5 read this same description, followed by information cues about the efforts made by the two core world powers in the race to assist Italy’s emergency – one representing a democratic regime (the USA) and another a non-democratic one (China). In Groups 2 and 4, the vignette presented the assistance of China and the USA as sufficient in terms of limiting the spread of the virus and its impacts (what we call for simplicity a “positive cue”), while in Groups 3 and 5, this assistance was presented as insufficient (what we call for simplicity a “negative cue”).

Below, we reproduce the English translation of the vignettes that participants read.Footnote 15 The first excerpt is the description that all groups read and the only text that the control group (Group 1) read. The second excerpt is the positive cue that those assigned to Group 2 (China-positive) read. Finally, the third excerpt is what Group 3 (China-negative) read. For those assigned to USA-positive (Group 4) and USA-negative (Group 5) cues, we only changed the international actor from China to the United States.

[description] The COVID-19 virus dramatically hit Italy in the spring of 2020, pushing the country’s health system to its limits. Given the dimensions of the emergency, existing medical supplies and personnel were not sufficient to properly face the situation.

[positive cue] During the peak of the emergency in Italy, it has been argued that China made a relevant contribution to assisting the national health system, sending ventilators, masks, and/or medical personnel. This contribution helped considerably reduce the number of positive cases and saved some lives.

[negative cue] During the peak of the emergency in Italy, it has been argued that China’s contribution to assisting the national health system, sending ventilators, masks, and/or medical personnel, was insufficient. A more substantial contribution could have helped considerably reduce the number of positive cases and could have saved some lives.

We are interested in the importance the public attaches to the regime type of potential allies. Therefore, in our treatments, we used one country representing a democracy (the USA) and one country representing an autocracy (China). While we could have used other countries representing these regime types, to meet our objective of measuring public diplomacy efforts by world powers and contributing to current IR debates on the “race to hegemony,” we specifically used the USA and China instead of other democracies/autocracies or a more abstract claim that a democracy or an autocracy have contributed to assisting Italy. As the USA and China indeed tried to assist Italy during the COVID-19 emergency, to avoid deception, we did not simply state that these actors had/had not assisted. Instead, we presented the assistance provided (equalized in form across both actors) in a positive/negative light, stressing that it has been argued that it was sufficient/insufficient. Finally, stating that “some argued” makes our treatments “claims of unattributed origin.” While this comes at the cost of being less attuned with how often – but not always – public diplomacy efforts are deployed (for example, with claims attributed to embassies or aid/development agencies), we opted for this approach to avoid potentially confounding endorsement effects. Overall, our treatment can be understood as a “conservative one,” as we did not prime respondents with shocking numbers, extreme events, or intense language.

Measures and analysis

Immediately after treatment assignment, the participants moved on to our outcome question. Our dependent variable is a measure of the importance that Italians attach to a country being democratic when it comes to Italy’s international relations. To capture this, we asked the following question: “In your opinion, Italy should privilege international relations with democratic countries, or is this aspect not important?” Participants could answer “Yes, it is important; No, it is not important; or Don’t know.”Footnote 16

We report results from models using order logit where “don’t know” is coded as an intermediate category between “important” and “not important.” In our view, this is the best approach as it does not merge categories that might have different meanings and does not have strong assumptions regarding the data generation process. As robustness checks, which we discuss in more detail in the Results section and report in full in the online Appendix, we worked with different operationalizations and model specifications to evaluate the sensitivity of the results based on our first operationalization. We re-ran our analysis using logit models, treating our dependent as dichotomous and merging “Don’t Know” and “Not Important,” as well as Heckman models for selection bias (Heckman, Reference Heckman1979), treating our “Don’t Knows” as “not don’t know at random” (NDKR).

To increase the precision of our estimates, we control for key socio-demographic and other key covariates(Kam and Trussler Reference Kam and Trussler2017). In addition, we test for COVID-19-related heterogeneous treatment effects, for which we interact with treatment effects and different indicators of “COVID exposure.” Before treatment assignment, we asked participants four different questions about how COVID had affected them and their close relatives.Footnote 17

Finally, before debriefing, we included an “attention check” question, in which we asked participants to recall the international actor that was mentioned in the vignette. 81% of participants recalled the name of the international actor correctly. We do not take this as equivalent to a manipulation check, as the question does not necessarily provide a strict indication of compliance; however, it gives us a sense of how attentive participants were when reading our vignettes.Footnote 18 We estimate treatment effects on both the entire sample and on those who recalled the name of the international actor correctly. Following Harden, Sokhey and Runge (Reference Harden, Sokhey and Runge2019), we present models with both the entire sample and the correct recall subsample to examine whether treatment effects are larger among those who recalled the international actor correctly.

Results

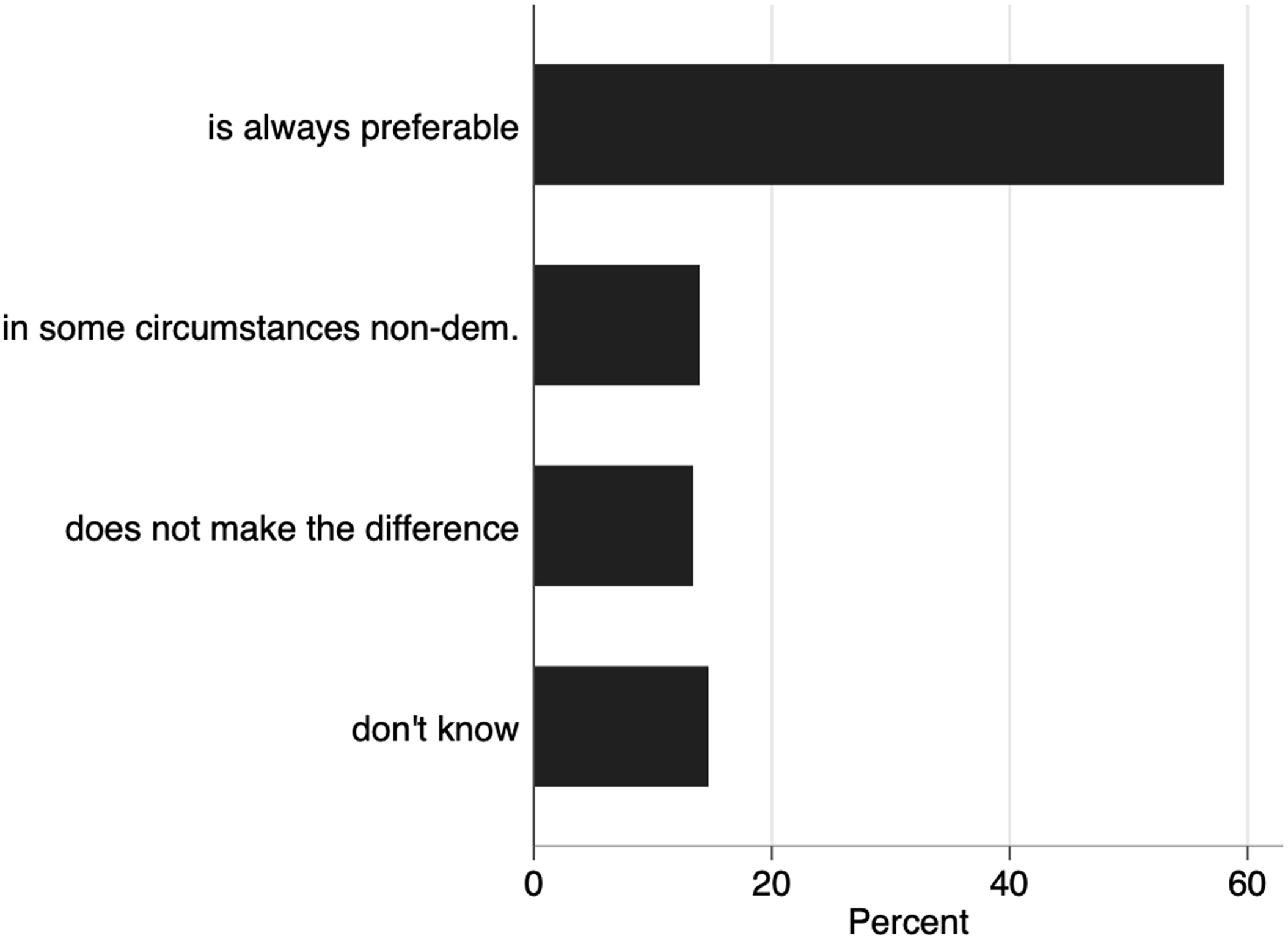

We start by presenting descriptive results for some key pre-treatment questions to set the stage. Figure 1 reports attitudes towards democracy.Footnote 19 It shows that we are indeed working with a largely pro-democratic public: 58% of our respondents consider that democracy is always preferable, 14% state that in some circumstances non-democracy is acceptable, 13% state that living in a democracy or non-democracy does not make a difference and 15% do not know.

Figure 1. Citizens’ attitudes towards democracy in their country.

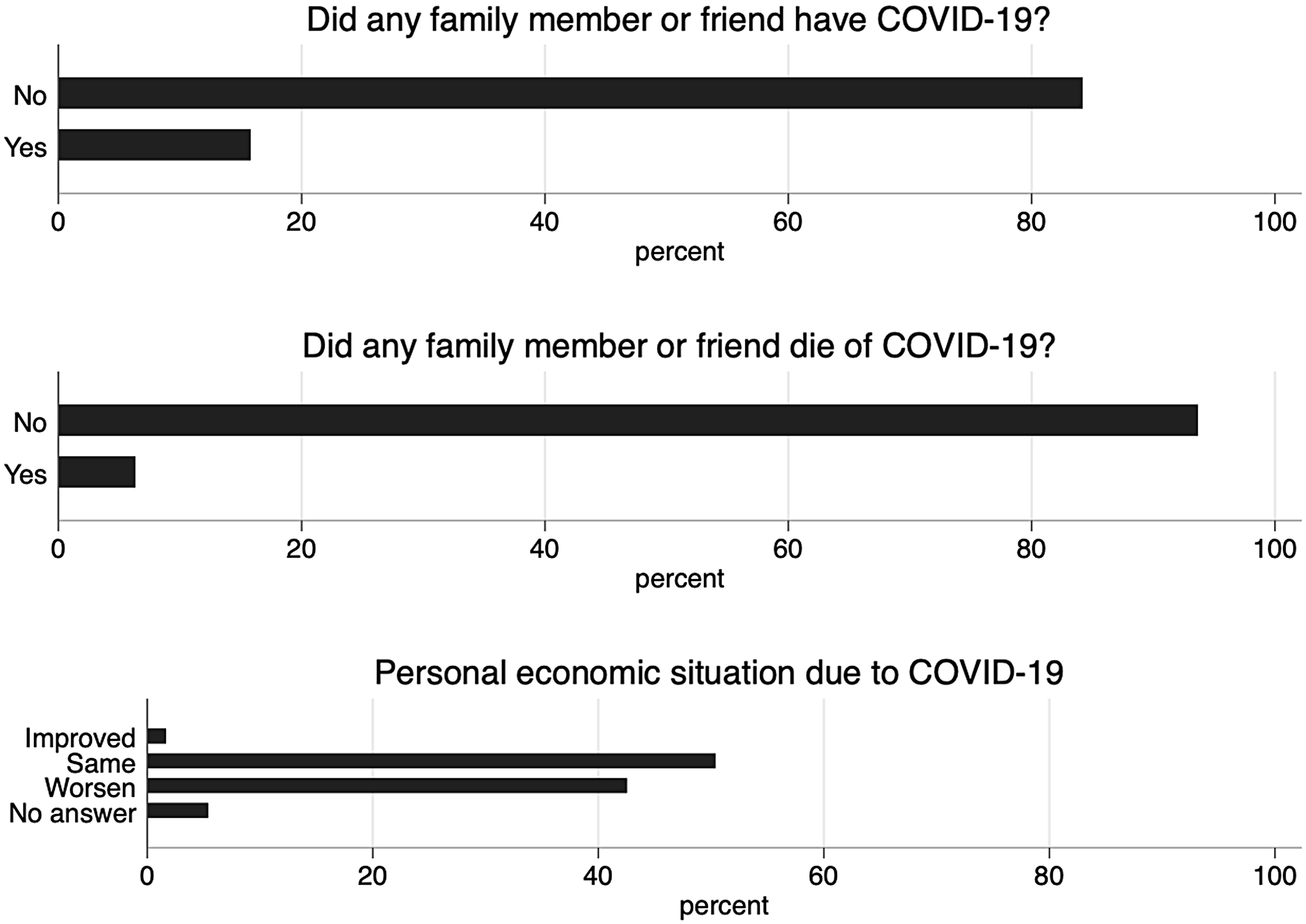

Figure 2 reports data on how our participants experienced COVID-19.Footnote 20 16% know someone who had COVID-19 and 6% reported that someone among their family or friends died due to COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic. Moreover, 43% stated that their economic situation worsened due to COVID-19. Overall, it can be restated that the impact of the pandemic was not marginal for Italians.

Figure 2. Citizens’ experiences of COVID-19.

Average treatment effects

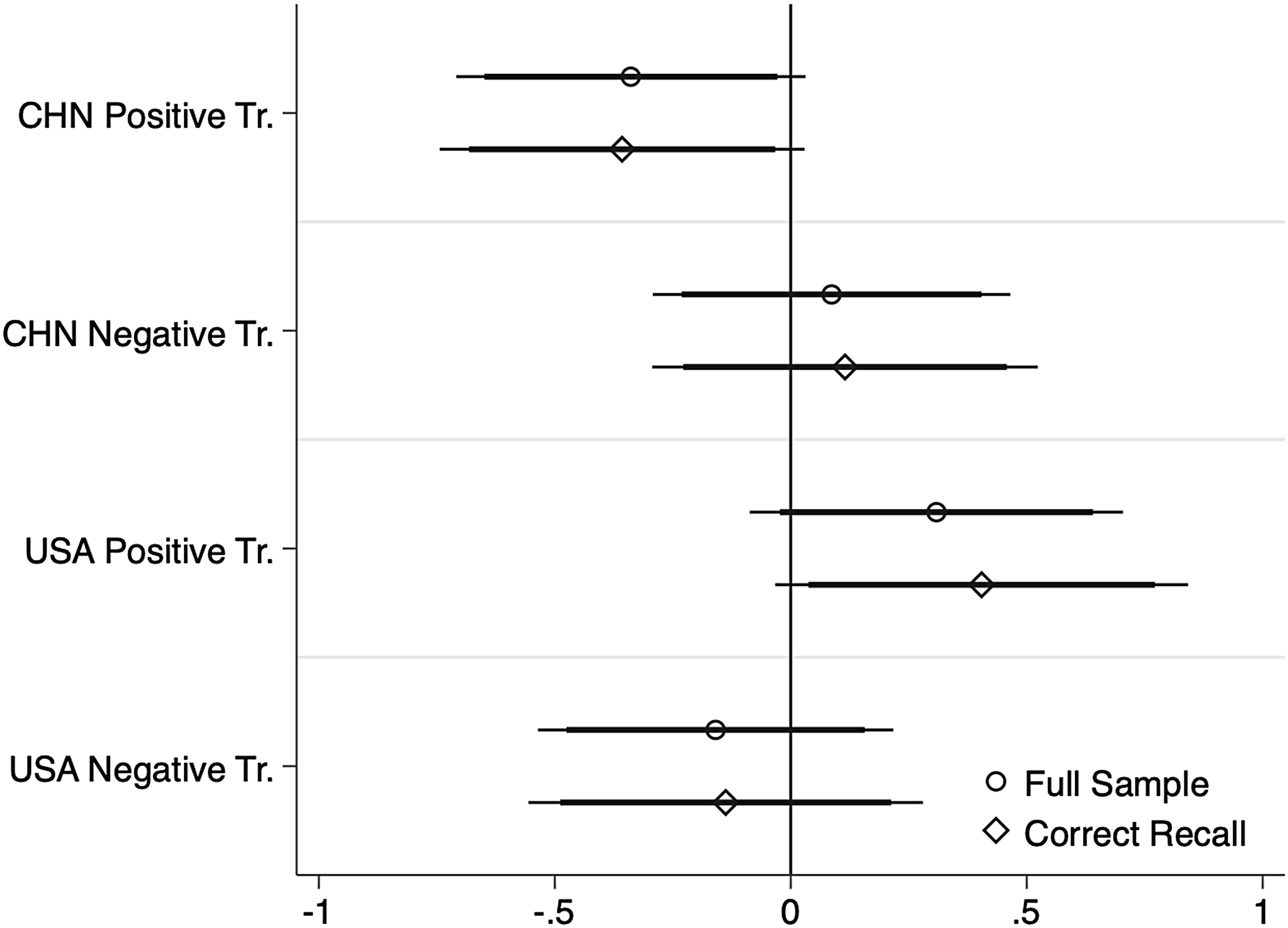

Our results in Figure 3 show that information regarding public diplomacy efforts by world powers can sway peoples’ attitudes towards international politics. However, these attitudinal changes were only partially in the direction we expected, with our results yielding support for our cognitive dissonance framework for China but not for the USA.

Figure 3. Is it important for an ally to be a democracy?

Note: Order Logit regression, confidence intervals of 90% and 95%.

We find support for Hypothesis 1. In contrast to what pre-pandemic attitudes would have suggested, we find that positive cues about China’s effort pushed Italians to discount the importance they attached to international allies being democratic regimes. This effect is statistically significant at 90% confidence. Relative to the control group, the probability that participants who read this vignette state that it is important that international allies are democratic decreases by 7%. In support for Hypothesis 2, we also find that negative cues about China’s efforts do not sway public attitudes. In contrast to Hypothesis 3, where we expected no effects, we find that positive cues about US efforts increased the importance that Italians attached to international allies being democracies. Yet, we see this effect is statistically significant at 90% confidence only when we focus on the “correct recall” subsample. Finally, regarding Hypothesis 4, while we see that attitudes move in the expected direction, we do not find a statistically significant effect that negative cues about US efforts decrease the importance that Italians attach to international allies being democratic regimes.

These estimates are obtained after controlling for other factors that could shape citizens’ attitudes towards intentional politics.Footnote 21 This includes support for democracy at home, consumption of daily information, interest in politics, political knowledge in the international realm, attitudes towards the government, and party identification. We also controlled for our measures of individual exposure to COVID-19. Observational analysis of these other factors shows that participants who stated that “Democracy at home is always important” have a 35% (P>0.000) higher probability of also stating that it is important to have democratic allies internationally. Daily consumption of information (85% of our sample)Footnote 22 and a fair or high interest in politics (46% of our sample)Footnote 23 increases the probability of preferring democracies as allies in international politics by 11% (P>0.007) and 9% (P>0.001), respectively, while having a fair knowledge of international politics (57% of our sample)Footnote 24 has no statistical association.

This analysis also shows that citizens’ attitudes towards the government – which at the time of the survey (July 2020) was composed of an alliance between Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S) and Partito Democratico (PD) – also matter. We created a 7-point scale of trust in the government and found that a unit increase in this scale, ceteris paribus, increases by 2% (P>0.000) the probability of preferring democratic allies abroad.Footnote 25 Finally, our results also show that being a right-wing voter (Lega) decreases by 8% (P>0.032) the probability of stating a preference for democratic allies, whereas being a centre-left voter (Partito Democratico) increases it by 28% (P>0.000), where voting for the M5S does not have a clear effect.Footnote 26 While this suggests that party preferences matter, we did not find heterogeneous treatment effects related to voting preference.Footnote 27

As we used specific countries in our treatments (China and the USA), one could reasonably worry that what we are observing are changes in attitudes towards these two countries and not necessarily towards the regime type they represent. As validation, we re-ran our models with a different dependent variable. We regressed treatment assignment on a dependent variable constructed from the following survey (post-treatment) question: To what extent each of the following actors is an important ally for Italy’s international relations?Footnote 28 Results from these analyses show that our treatments do not affect attitudes towards relations with the USA or China (see Figures A5 and A6 in Appendix). Not observing any effects on attitudes towards China or the USA, strengthens our claim that information about public diplomacy efforts from these countries sway attitudes towards how central the regime type of potential allies is.

As our main models treat “Don’t Know” as an intermediate category, we re-ran our analysis with different operationalizations and models to evaluate the sensitivity of the results based on our initial operationalization. First, we ran logit models where we treat our outcome measure as dichotomous (“important” versus “not important”), collapsing the “don’t know” (DK) and “not important” responses on the assumption that a “DK” did not signal a positive reaction (See Figures A7a and A7b in Appendix). Second, while there is no clear convergence on how to treat DKs best, we found some helpful guidelines in the literature (e.g. King et al., Reference King, Honaker, Joseph and Scheve2001; Kroh, Reference Kroh2006; Little and Rubin, Reference Little and Rubin2019; Luskin and Bullock, Reference Luskin and Bullock2011). The key recommendation from this literature is first to explore what type of “missing data” one is dealing with and then select the appropriate approach in light of the type of “missingness.” There are three basic types: data missing completely at random (MCAR), data missing at random (MAR), and data not missing at random (NMAR). As we report in the Appendix (Figure A8), our DKs are not MCAR or MAR, but “not don’t know at random” (NDKR). Under these conditions, dropping the DKs would likely affect the randomization and imply excluding respondents with systematic characteristics: lower political knowledge, lower preferences for domestic democracy, lower consumption of daily information, and less interest in politics and support of the Democratic Party. Therefore, dropping the DKs was not appropriate. Given that our DKs are not random, randomly imputing them to Yes and No was also problematic. An appropriate alternative is to treat our NDKR with Heckman models for selection bias (Heckman, Reference Heckman1979).

Consequently, we conducted a third robustness check using a Heckman probit selection model (Kroh Reference Kroh2006) with the entire sample and subsampling according to democratic preferences. The results from these tests, which we report in the Appendix (Figure A3), are largely consistent with results from our main models: the directions are the same, but only the effect of our China-Positive treatment remains significant at 95%. The effect of the USA-positive treatment we see when working with the “correct recall” sample in our main models disappears. These findings are even more consistent with our cognitive dissonance framework and support our hypotheses more strongly. Still, we opted to use the order logit model rather than the Heckman model as our main model because we find a core assumption of the selection model too strong: the ability to fully specify the data generation process in the first equation.

Do attitudes towards democracy matter?

Our expectations are based on the theoretical idea that citizens will experience cognitive dissonance based on their democratic congruence/incongruence towards a democracy/autocracy. Our analyses above were performed on the assumption that, on average, the Italian public is pro-democratic. However, there are good reasons to expect heterogeneity in how important citizens think democracy is in their country. Moreover, after performing due balance checks, we found that while most variables were balanced across the experimental conditions, a few were not, even if the randomization procedure was otherwise correctly executed by the survey firm.Footnote 29 Particularly concerning for us was the fact that positive attitudes towards democracy were imbalanced for the “China-positive treatment.” Where the other groups have a mean of 56% with positive attitudes, the mean for the subgroup treated with the China-positive treatment is 64%, with this 8% difference being statistically significant. Similarly, the “China-negative treatment” has a lower mean (51%) than the other groups. Hence, to both correct this imbalance and relax the assumption of democratic congruence among the Italian public, we explore whether subsampling to compare groups with strong attitudes towards democracy at home makes a difference.Footnote 30

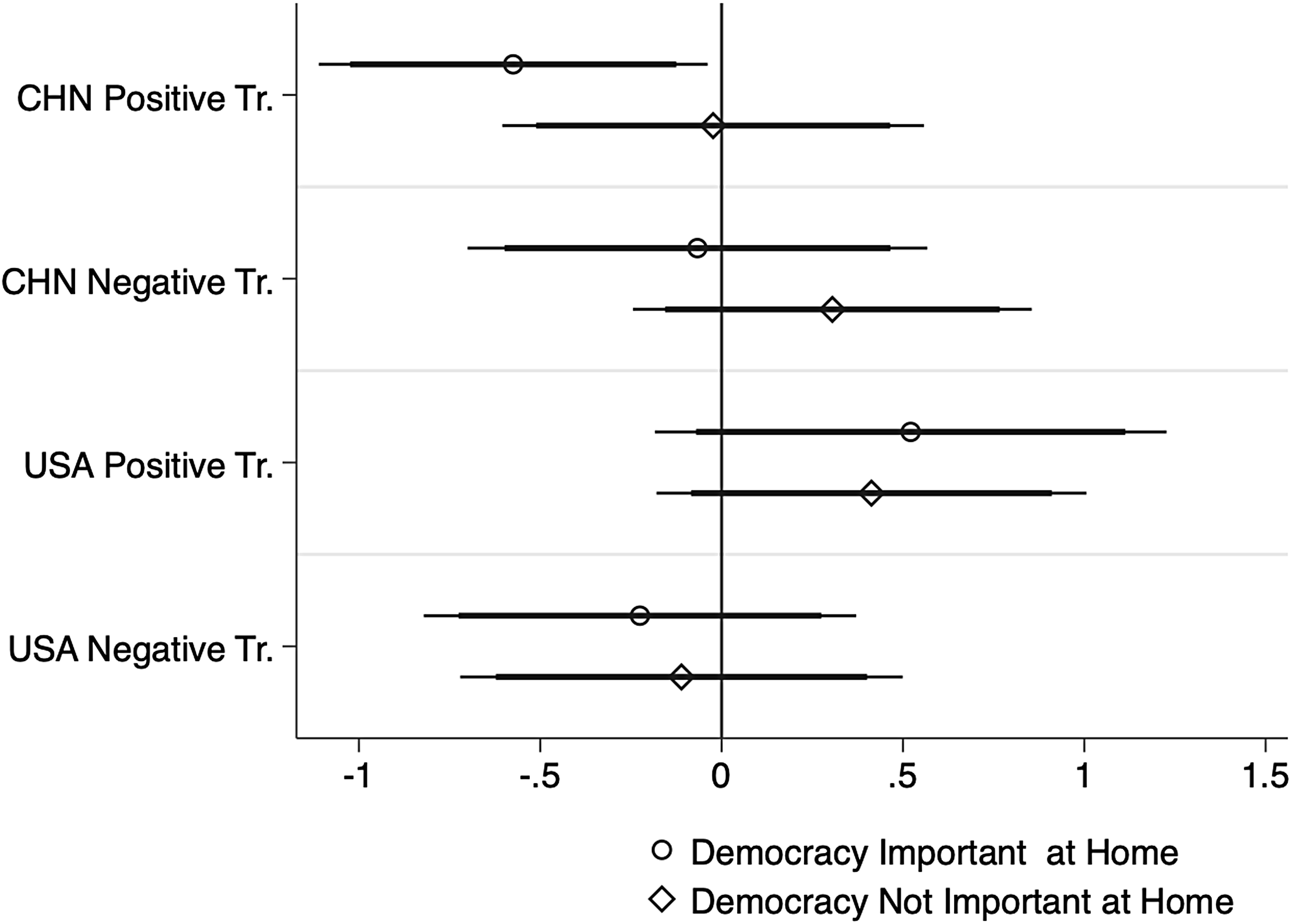

Figure 4 plots estimates of treatment effects comparing a subsample of respondents who answered that democracy at home is always important (circle) with another subsample of respondents who answered that it is not important to have democracy at home (diamond). Our findings are partially consistent with our cognitive dissonance framework: it is supported in the case of respondents that experience a “China-positive treatment” and stated that “democracy is important at home.” For the “USA-positive treatment,” we find that, even though the direction of the effect is consistent for both samples, their statistical significance does not reach standard levels.

On the other hand, the “China-positive treatment” effect is statistically significant only for those who stated that “democracy is important at home.” These respondents discount the importance of allies being democratic because their preference for democracy at home clashes with the positive cue of China. The AME for this treatment decreases by 8% the probability that the respondent will give importance to international allies being a democracy when presented with a positive cue about China’s efforts.

Figure 4. Attitudes towards democracy at home and for allies.

These results show that, on average, having a strong preference for democracy at home is a strong predictor of preferring democratic allies abroad. This is quite an intuitive finding. Yet, they also suggest that the impact of public diplomacy by a non-democratic international actor is stronger among a public with more positive views on democracy at home. The incongruence between the regime type that an individual prefers at home and the positive actions of an international actor of a different regime type pushes that individual to update their preferences about the importance of regime type in international politics. “I care about democracy at home, and yet I receive assistance from an international actor that is not a democracy; hence, regime type might not matter much for international politics.” In other words, if a citizen is a firm supporter of democracy, she expects a lot from democracies regarding international assistance in hard times and little from non-democracies. When she sees other democracies assisting, this does not significantly shift her attitudes as it reaffirms her political views, but when she sees a non-democracy providing assistance, this goes against her expectations and thus invites her to reassess the importance that she attaches to regime type in international politics.Footnote 31 While these results bound the generalizability of our findings, they are perfectly consistent with our cognitive dissonance framework.

Did COVID exposure matter?

How individuals experienced COVID-19 could also mediate our effects, as those more deeply affected by COVID-19 might be less sensitive to positive information about the efforts international actors made to support Italy. Those deeply affected by COVID-19 likely believe that support from any actor, regardless of public diplomacy efforts, was insufficient. Given this possibility, we evaluate a possible dampening effect due to an incongruence between the positive cue and the real lived experience. Doing so is particularly important considering that, while the impact of COVID-19 was particularly profound in Italy (especially in its first wave), there was wide variation in exposure within the country and between individuals. While our models already controlled for how hard COVID-19 hit our respondents, and none of our measures yielded any statistically significant effect, we further estimate heterogeneous treatment effects with exposure to COVID-19.Footnote 32

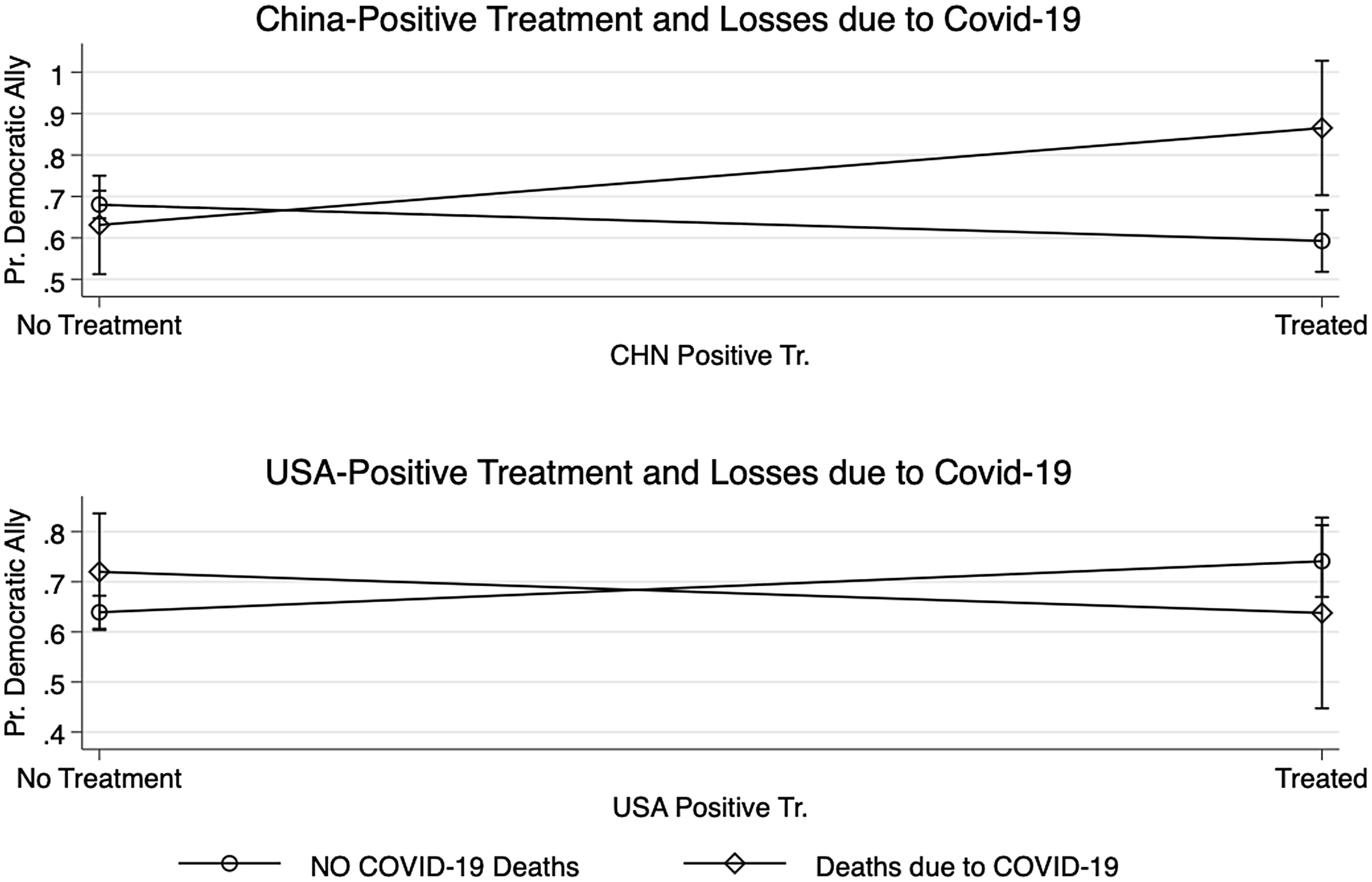

These analyses show that having relatives or close friends who had COVID-19 in the first wave, or considering that the pandemic had a negative financial effect on their economic situation, does not interact with our treatments. Yet, as Figure 5 shows, whether respondents knew someone who had died from COVID-19 (a proxy to “deeper impact”) did affect how they reacted to our treatments. In particular, these results show that the effects of China-positive cues are more sensitive to (deep) exposure to COVID-19. Participants exposed to positive information about China’s efforts to support Italy, who also knew someone who had died from COVID-19 (diamond), have a higher probability of preferring democratic allies than those who did not experience loss (circle).

Figure 5. Treatments and COVID-19 experience.

That this subgroup of people does not react to our treatment the same way as the rest of the treated participants is reasonable, as the dramatic way they experienced COVID-19 offsets any positive information about others trying to assist. This is especially likely if we consider that our cue explicitly noted that, according to some, the assistance provided helped “save some lives.” If someone you know died from COVID-19, it is very unlikely that you would believe that the assistance provided by an international actor actually helped.

Moreover, it is important to recall that during the COVID-19 crisis, especially in the first stages, the perception (justified or not) that China was to be blamed for the situation given that the pandemic started in that country, was widespread. This further helps us make sense of this result: the fact that respondents who were more deeply affected by COVID do not react or react negatively to the China-positive cue may be more likely to look for someone to blame (China), seeking accountability amidst their grief. This makes them insensitive – or even angry – to positive cues about China, which they might perceive as propagandistic messaging.Footnote 33

However, this dampening effect is not as clear when it comes to the USA-positive treatment. While estimates move in the same direction, the difference in the effects between those who experienced loss due to COVID-19 (diamond) and those who did not (circle) is not statistically significant. This might suggest that, given baseline expectations about the behaviour of international actors by a pro-democracy public, the clash between positive information and the real lived experience is stronger when positive cues are about non-democracies. A largely pro-democracy public “punishes” non-democracies for insufficient support more than democracies.

Conclusions

Interventions in domestic affairs come in different forms, one of which is public diplomacy. In their current race for global hegemony, the USA and China saw the COVID-19 emergency as a window of opportunity to exercise public diplomacy backed up by health aid to improve their international standing and (re)establish themselves as the leaders in the global response to the pandemic. This article investigated whether these efforts affect citizens’ attitudes and preferences towards international politics. In particular, we studied attitudes regarding how important it is that the international allies of one’s country are democratic.

We designed and conducted a survey experiment in Italy in July 2020, right after the first COVID-19 wave, and found that information cues about the assistance provided by global powers can shape attitudes towards international relations. Positive information about efforts by the USA to assist Italy in facing the health emergency led citizens to attach more importance to international allies being democratic regimes. While this was to be expected given prior pro-democratic and pro-USA attitudes of the Italian public, we also found that positive information about Chinese efforts led participants to discount the importance they gave to international allies being democratic. We further learned that these effects depend on the citizens’ support for democracy at home. The effect for China was strongest among those who strongly supported democracy at home; we contend that a cognitive dissonance framework and the coping mechanism of dissonance reduction help make sense of these findings.

Overall, our results suggest that health aid as a public diplomacy tool can have discernible effects in times of crisis. Italy – a democracy since the end of WWII, a member of NATO, a founding member of the European Union, and a member of the G7 – is clearly a hard case for Chinese public diplomacy. Yet we have seen that amid the COVID-19 emergency, Italian citizens primed with positive cues about Chinese support had a lower tendency to firmly state that being a democracy should be a central feature of Italy’s international allies. However, we found that public diplomacy from a democratic “old” ally like the USA also mattered, suggesting that preference substitution should not be assumed in the global race for hegemony. Positive attitudes towards the USA can be accompanied by similarly positive attitudes towards China.

While these findings are important and novel, we want to close by stressing clear scope conditions, recognizing limitations, and identifying avenues for further research. First, our findings do not represent the “usual” effect of public diplomacy. The effects we found speak to public diplomacy in times of crisis (and during a particularly acute crisis!). Therefore, we should not assume they are generalizable to “normal” times. Second, the scenario that we explored is one of public diplomacy efforts backed up by actual material supply (e.g. masks and ventilators). As such, whether our findings replicate in situations in which public diplomacy efforts are mainly discursive, with no material backing, is an empirical question that future research should take on. Third, with our research design, we cannot assess how permanent these effects are. Therefore, we can only claim that public diplomacy efforts in times of crisis can shape attitudes in the short run.

Fourth, while Italy is an appropriate and significant case, it remains a single case study, and future work should explore these findings comparatively with other “old allies” of the USA, inside and outside of Europe, and in countries with more positive attitudes towards China. Fifth, future research should explore whether public attitudes towards the importance of regime type in international partnerships change when public diplomacy efforts come from countries different from China and the USA. Finally, we opted to work with claims of unattributed origin, which is often not how public diplomacy efforts are deployed. Future research, perhaps using endorsement experiments, should explore whether the effectiveness of public diplomacy changes according to the identity of the “promoter”: embassies, aid/development agencies, politicians, experts, and the media.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773924000225.

Data availability statement

Under conditional acceptance data and replication procedure will be shared with EPSR and posted on authors’ websites.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Vincenzo Bove, Lorenzo De Sio, Farsan Ghassim, Todd Hall, Davide Morisi and Duncan Snidal for their comments. Three anonymous reviewers with their suggestions improved our article, we thank them.

Funding statement

We acknowledge funding: Unige 100015-2018-FC-CURIOSITY_001.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical statement

The study was pre-registered at Evidence in Governance and Politics (EGAP) and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Genoa 09/06/2020. IRB protocol # 2020.5.