Introduction

Recent literature documents the emergence of a conflict revolving around globalization-related issues: The ‘globalization cleavage’ (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi2012) or ‘transnational cleavage’ (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018) arguably pits ‘cosmopolitans against communitarians’ (Teney et al., Reference Teney2014; Zürn and De Wilde, Reference Zürn and de Wilde2016), ‘cosmopolitans against nationalists’ (e.g., Kuhn et al., Reference Kuhn2017), or ‘liberals against particularists’ (Bornschier, Reference Bornschier2010). In party politics, Green, Alternative and Libertarian (GAL) parties oppose Traditionalist, Authoritarian and Nationalist (TAN) parties (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe2002). Whilst there are different terms used, scholars agree that what we are essentially facing is a ‘struggle over borders’ (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde2019) with some people, parties and other organizations favoring more ‘integration’ – open borders for migration and trade, international collaboration on transnational issues like climate change, within the framework of the European Union (EU) and within international organizations like the World Health Organization – whereas others want the opposite: ‘demarcation’ (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi2008).

Globalization drives this new cleavage, whether through direct exposure or its class-specific consequences (Langsæther and Stubager, Reference Langsæther and Stubager2019). Economic, cultural, and political globalization have reduced the importance of nation state borders (Held et al., Reference Held1999). Some see opportunities in world culture and international careers, while others see a threat to their traditions and livelihood. And yet, how pronounced this globalization cleavage has become varies across countries. All affluent, democratic, industrialized countries are affected by globalization, but they do not all feature the same lines of conflict. If the cleavage was a direct, linear effect of globalization, then the most open economies – small, Western European, rich countries – should see the most pronounced conflict. This is not the case. We do not see a single dimension of conflict over globalization-related issues. Differences of opinion over cultural integration often do not align with differences of opinion over economic integration, and frequently not even with political integration into international systems (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde2019; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi2008). This raises questions of how crystallized the new cleavage is (cf. Bornschier et al., Reference Bornschier2021).

In this article we take on this challenge by posing the overarching question: ‘To what extent is the globalization cleavage crystallized?’ We use the word ‘crystallization’, because it implies both a process of solidification and one of clarification. As something crystallizes, it takes solid rather than fluid form and becomes less opaque, if not fully transparent. A cleavage becomes crystallized, when two opposing societal groups become easier to identify in terms of their structural, organizational, and normative aspects (Deegan-Krause, Reference Deegan-Krause and Berglund2013). The more internally uniform and externally distinct cleavage coalitions become, the more crystallized the cleavage is. Since the globalization cleavage is theorized to contain cultural, political, and economic dimensions (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi2012), it would be more crystallized the more these dimensions align. In other words, the more individuals on the cosmopolitan side approach the theoretical ideal type of what it means to be cosmopolitan and the more individuals on the communitarian side reflect ideal-typical communitarians, the more crystallized the cleavage is.

Our investigation follows a three-pronged approach. First, recent evidence shows that crystallization is directly related to the extent to which globalization-related issues are politicized (Walter, Reference Walter2021). Since this politicization varies between countries due to different opportunity structures and actor strategies (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde2016), our first aim is to investigate to what extent individuals’ preferences for globalization-related policy issues align across different countries. Secondly, we consider the alignment of normative beliefs of individuals along the new cleavage. While political cleavages have three components: structural, organizational, and normative (Deegan-Krause, Reference Deegan-Krause and Berglund2013), research on the normative component of the globalization cleavage appears to be a particular challenge (cf. Mader et al., Reference Mader2020: 1527). At the party level, ideologies including components of environmentalism and libertarianism have been identified on the cosmopolitan side (e.g., Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1988) and components of traditionalism, authoritarianism, nationalism, and nativism on the communitarian side (cf. Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018). At the individual level, however, it has proven to be challenging to capture the depth of the normative component. Policy preferences on cultural issues are often taken as proxies for deeper values, but studies on values, ideologies, and collective identities remain comparatively few and recent (but see Dennison et al., Reference Dennison2020; Baro, Reference Baro2022; Bornschier et al., Reference Bornschier2021).

Our investigation goes beyond policy preference alignment as core of the normative component. While we know preferences over European integration and immigration are often aligned, such attitudes are perhaps only the tip of the iceberg of a fully-fledged normative component. Digging deeper than attitudes, we look into whether the alignment in individuals’ normative beliefs – specifically their definition of collective identity and attending values and virtue perceptions – vary and correlate with their policy preferences. That is, we analyze how and to what extent variations in the prioritization of values and virtues parallel variations in policy preferences. Lastly, we zoom in on a potential crystallization along the organizational dimension. In this step, we focus on two important components, namely the party choice of individuals and the degree to which party preferences match the variance in policy preferences and normative values.

We employ a paired comparison research design (Tarrow, Reference Tarrow2010) by studying novel public opinion data in Norway and the UK. With the Brexit referendum in 2016, the UK recently saw a major catalyzing event to crystallize the new cleavage. EU membership and immigration – the two central issues in the new cleavage – were heavily politicized in the referendum campaign and the negotiation period afterwards. It arguably formed a critical juncture in political discourse (Zappettini and Krzyzanowski, Reference Zappettini and Krzyzanowski2019) and generated lasting affective polarization between leavers and remainers (Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt2020). There were referendums about EU membership in Norway too, in 1972 and 1994, but that is a long time ago. Crucially, the issue of immigration was not a major theme in the Norwegian referendum campaigns. This became a major salient issue in Norwegian politics only from the 2009 election onwards, long after the last referendum (Hesstvedt et al., Reference Hesstvedt2021). Following a controversial referendum campaign, the question of EU membership was effectively depoliticized. Thus, Norway and the UK represent quite different situations. In the latter, there has just been an intense debate over EU membership, to the degree that it has shaped people’s identities (Sobolewska and Ford, Reference Sobolewska and Ford2020), and where this issue was strongly connected to immigration and other globalization issues in the political discourse (Evans and Menon, Reference Evans and Menon2017). In Norway, migration is an important political issue (Bergh and Karlsen, Reference Bergh, Karlsen, Bergh and Aardal2019), but this is mostly a question of non-Western refugees and is rarely related to other globalization issues such as European integration or free trade. The last referendum on EU membership was held three decades ago. While immensely divisive, it did not connect European integration to immigration in the way the Brexit referendum did. Thus, we see these two cases as respectively most likely (the UK) and least likely (Norway) cases for globalization-cleavage crystallization within the West-European context. A comparison between them may shed light on the range of crystallization within Europe.

A new globalization cleavage

According to cleavage theories, societal revolutions led to long-standing conflicts between different groups within societies (Bartolini and Mair, Reference Bartolini and Mair1990; Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967). Cleavage theorists identify three key components to a cleavage (Deegan-Krause, Reference Deegan-Krause and Berglund2013). The structural component reflects individual citizens’ characteristics, like religion and class. The organizational component consists mostly of political parties, but other organizations such as trade unions or churches can also contribute. The normative component of cleavages, however, is not as extensively studied as the others. Attitudes and collective identity are part of it, but the existence of ideologies that are more encompassing than a set of policy preferences remains often overlooked.

Two developments since the 1980s opened new issue venues and new political parties like green parties and populist radical right parties started capitalizing on it. Hence, a discussion about the rise of a new cleavage ensued. First, environmental degradation fueled an environmental movement, including the emergence of green parties (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1988). Supporters of green parties often hold ‘post-material’ values (Inglehart and Welzel, Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005) focusing much less on economic issues than supporters of class cleavage parties do. Second, immigration and worries about the failure of multiculturalism started to fuel the rise of far-right populist parties. Additionally, the process of European integration gained new steam in the mid−1980s with the Single European Act and completion of the internal market. The new cleavage was described as GAL-TAN, pitting GAL forces against Traditional, Authoritarian and Nationalist ones (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe2002). Globalization and its side effects is the societal revolution driving this cleavage, as highlighted by Kriesi and colleagues (Reference Kriesi2008, Reference Kriesi2012), where those favoring integration support mainstream parties while those favoring demarcation support far-right (and to some extent far-left) parties.

Bartolini (Reference Bartolini2005) draws on classic Rokkanian political sociology to focus attention on the role of political center formation. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the Westphalian nation state developed strong administrative capacities and increasingly regulated citizens’ lives. This made it less easy for people to ‘exit’. Citizens opted for ‘voice’ instead of exit and mobilized at national level to influence this power center (Bartolini, Reference Bartolini2005). Deconstructing the nation state through globalization and opening borders provides new opportunities for exit, but only to those with mobile assets like capital and flexible skills obtained through higher education. Calhoun (Reference Calhoun2002) goes as far as to describe cosmopolitanism, the support for globalization, as the class consciousness of frequent travelers. It is thus understandable that mobilization against it comes primarily from those without the mobility to enjoy the opportunities of globalization (Teney et al., Reference Teney2014, Hellwig, Reference Hellwig2015) and that this opposition is more forcefully expressed than support for open borders. In 2016, anti-globalization forces booked two major victories with the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump. In addition, governments in countries like Poland and Hungary have become increasingly hostile to both immigration and the EU. With anti-globalization forces in power in several countries, the backlash to globalization generates its own backlash, in a dialectic turn of events. Liberal mobilization and the pro-European movement reached new heights in the UK after Brexit, and in Poland after the PiS electoral victory. In this way, a catalyzing event like Brexit may first function to galvanize communitarian forces and later to galvanize cosmopolitans, thus functioning to crystallize the cleavage.

The normative component of the globalization cleavage and bones of contention

The first two components of the new globalization cleavage are extensively studied. A range of studies point to education as the key structural factor (Hainmueller and Hiscox, Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2006; Hakhverdian et al., Reference Hakhverdian2013). Older people, men, and whites tend to vote more for anti-globalization parties than the young, women, and people with migration backgrounds (Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2016). Radical right and green/social liberal parties perform a key role in establishing the organizational component of the new cleavage, where the former do so by combining opposition to immigration and the EU often with criticism of the political elite (Mudde, Reference Mudde2019) and the latter do so by integrating a pro-immigration and pro-EU stance with environmentalist positions and ‘older’ liberal issues, such as gender equality and LGBT rights (cf. De Vries, Reference De Vries2018).

We unpack the possible elements constituting the normative component of this cleavage through four ‘bones of contention’ (Zürn and De Wilde, Reference Zürn and de Wilde2016) that allegedly form the building blocks of cosmopolitan and communitarian ideologies. The first consists of attitudes on globalization-related issues that capture preferences for the permeability of borders. Should people, goods, norms, etc. be (more) freely allowed to travel across nation-state borders? Items here capture preferences on immigration, free trade, globally combating climate change, and human rights. We also consider cosmopolitan–communitarian priorities. To what extent should society prioritize different issues (e.g., protecting the environment, national defense, and so on) to face major global challenges? A second ’bone’ considers international authority. To what extent should inter- and supranational institutions like the UN and EU be empowered to decide on a range of policy issues? The third bone of contention captures collective identity, or the relevant community individuals associate with. Finally, the fourth bone of contention captures justifications or the invocation of moral, ethical, and instrumental values to base policy preferences on. Part of the value difference between cosmopolitans and communitarians, as argued by key scholars of populism (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004; Müller, Reference Müller2017), lies in the importance ascribed to majoritarian versus liberal components of democracy. Others see variation in the extent to which people cherish different virtues – particularly courage (MacIntyre, Reference MacIntyre2007) – as the decisive difference between cosmopolitans and communitarians. Together these four bones of contention form the normative component of the globalization cleavage (Merkel and Zürn, Reference Merkel, Zürn and de Wilde2019; Zürn and De Wilde, Reference Zürn and de Wilde2016). These bones are theorized to logically relate, due to the underlying structuring dimensions of universalism vs particularism and individualism vs collectivism. That is, true communitarians will oppose open borders, oppose the transfer of authority to international institutions, hold strong local or national identities, maintain majoritarian understandings of democracy, and cherish courage because of their particularist and collectivist world-views. True cosmopolitans, on the other hand, support open borders and international authority, have an individual or international identity, and cherish liberal understandings of democracy and values as embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights because of their underlying universalist and individualist world-views.

We thus expect:

H1: Individuals who oppose the free travel of goods, services and people across borders are more likely to oppose transferring political authority to institutions beyond the nation state and more likely to feel attached to local, regional and national communities.

Recent research into the normative component of this cleavage focuses on underlying value structures. Going beyond policy preferences, these studies relate voting for Brexit (Dennison et al., Reference Dennison2020) or far-right populist parties (Baro, Reference Baro2022) to individual Schwartz values. In our approach, we start from a different angle. Acknowledging the formative role thinkers like Marx and Hayek have played in the crystallization of the class cleavage, we draw on the works of cosmopolitan thinkers (e.g., Pogge, Reference Pogge1992; Held, Reference Held1995) and their communitarian critics (e.g., Sandel, Reference Sandel1998; Walzer, Reference Walzer1983; MacIntyre, Reference MacIntyre2007) to identify the elements of ideal-typical cosmopolitan and communitarian ideologies at individual level and then proceed to analyze to what extent real citizens approximate those ideal types. The more they do so, the more crystallized the cleavage.

In a fully crystallized scenario: 1) different policy priorities among citizens stem from a different focus between the rights of individuals versus collective needs, 2) communitarians have an inclination to value majoritarian principles of democracy over liberal and representative ones because they flow from the valuation of self-determination rights of the collective; and 3) communitarians place a stronger emphasis on the importance of Aristotelian virtues, particularly courage, arguably lost in the course of the Enlightenment. Cosmopolitanism rests on the three principles of individualism, universalism, and generality (Beck, Reference Beck2005; Held, Reference Held, Brown and Held2010; Pogge, Reference Pogge1992). These underpin a strong support for human rights, by force, if need be. This is because individualism and universalism lead cosmopolitans to value the integrity of human individuals over the sovereignty of nation states, as codified in the Responsibility to Protect principle (Bellamy, Reference Bellamy2009). They also underpin an endorsement of the all-affected principle in democracy and the subsequent argument in support of global governance institutions to address transnational problems. Ultimately, as with liberalism fostered through the Enlightenment, the bedrock to cosmopolitanism is an understanding that the human individual is the ultimate unit of moral concern, not any particular community. This individualism subsequently elevates egoistic practices such as the pursuit of happiness and wealth to the status of values. Key communitarian philosophers, in contrast, stipulate that people are not atoms. Their ability to form relationships of trust is limited to their surroundings, thus deeply embedded, and molded within communities. Whether it is the family, tribe, nation, or something else, these communities shape who we are, whom we can relate to, and thus set the boundaries for the establishment of justice and solidarity. Sandel (Reference Sandel1998) postulates that too much prioritization of individual rights and freedoms comes at the detriment of collective needs. In contrast to individualism fostered through the Enlightenment, the romanticism at the base of many nationalist movements emphasizes the needs of the collective over individual rights. In short, all of the policy preferences, priorities, understandings of democracy and virtue appreciations we analyze as likely building blocks of cosmopolitan and communitarian ideology, ultimately stem from the universalism and individualism underpinning cosmopolitanism and the particularism and collectivism at the core of communitarianism. Building on this, we expect that:

H2: Individuals who are in favour of demarcation with regards to globalization are more likely to see challenges to the collective’s capacity to meet its needs as most important issues facing the country.

Another element underpinning the normative foundations of ideologies is the different understandings of what democracy is and ought to be. Where the individualism in cosmopolitanism resonates with the ‘liberal’ side of liberal democracy, notably rule of law and separation of powers, communitarianism resonates more with the ‘democracy’ part, particularly collective self-determination, and a community’s imperative to ‘… attend to the needs of its members as they collectively understand those needs…’ (Walzer, Reference Walzer1983: 84). Cosmopolitans and communitarians have different ideas about what society’s most pressing problems are. Where cosmopolitans prioritize individual rights, communitarians focus more on the needs of the collective. Hence, they have a different idea about how to pursue justice (Sandel, Reference Sandel1998: 11ff). As Walzer (Reference Walzer1983) suggests, a just society from a communitarian perspective is built on the collective will of its members. If the ideal society results from a negotiation between equal members, the ideal application of democracy becomes a means to foster collective self-determination. Conversely, cosmopolitans imagine just society as one built on safeguarding and nurturing individual liberties. Their understanding of democracy is less focused on collective will-formation and more on the protection of individual rights and freedoms. Building on this philosophical discussion, we expect:

H3: Individuals who have a stronger preference for demarcation are more likely to emphasize collective self-determination as the most important aspect of democracy.

MacIntyre (Reference MacIntyre2007) sees modern day cosmopolitanism as rooted in the Enlightenment and based in the thought of Kant. In the course of the Enlightenment, MacIntyre argues, we slowly replaced virtues such as courage and a sense of duty with individualistic values, such as justice, equality, freedom, and wealth. They align with the modern cosmopolitan ideal where citizens say ‘I chose to do so-and-so, because I wish it’. This stands in contrast to the more romantic ‘heroic societies’ from before the Enlightenment (MacIntyre, Reference MacIntyre2007: 127), where people were motivated to act based on duty. It is communitarian in the sense that courage and duty inherently subordinate the individual to the collective. In the case of full crystallization, one may expect an appreciation of certain classic Aristotelian virtues to be more important to communitarians than to cosmopolitans. This applies particularly to courage, closely related to a sense of duty (cf. Hannah et al., Reference Hannah2007). Thus, we expect that:

H4: Those who are more in favor of demarcation and collective needs are more likely to prioritize courage as an important virtue.

After this elaborate analysis of the depth of and internal consistency of the normative component, we end our research by investigating the relationship between the normative and organizational components. Based on a simple rational framework of voting, we expect that individuals are more likely to vote for political parties advocating demarcation, the more their beliefs are affected by communitarian norms and preferences. Therefore, we expect that:

H5: Individuals who lean more toward the communitarian side of the globalization cleavage are more likely to vote for parties advocating demarcation.

The logics spelled out above are likely to be more advanced in countries where the issues are highly politicized in recent times and where political actors have bundled these issues together in the political discourse. This is because, in the course of politicization, ideologically incoherent arguments – in our case combining elements of both cosmopolitanism and communitarianism – are likely to be victims in the process of polarization, where extreme and consistent sound bites crowd out nuanced and obfuscated arguments. The Brexit referendum of 2016, and subsequent negotiations between the UK and the EU, constitute an ‘episode of contention’ (Tilly and Tarrow, Reference Tilly and Tarrow2007). It is a period in which globalization-related issues were politicized, increasing salience and polarization. The globalization cleavage should be more crystallized during and shortly after such an episode. Hobolt and colleagues (Reference Hobolt2020) confirm that the Brexit referendum created lasting collective identities of Remainers and Leavers and affective polarization between them. Key in the Brexit referendum was the discursive linkage between migration and EU membership. The Leave campaign explicitly argued that leaving the EU was necessary to limit immigration. Brexit thus constitutes a ‘critical juncture’ in the crystallization of the globalization cleavage (Gifford, Reference Gifford2020; Zappettini and Krzyzanowski, Reference Zappettini and Krzyzanowski2019). In contrast, the two EU referenda in Norway were a long time ago. The issue of EU membership was very contentious at the time, but has since been successfully depoliticized (Fossum, Reference Fossum2010). In addition, the Norwegian far-right populist party is not as extreme as many of its ideological brethren. It is skeptical of immigration, but ambiguous about European integration.

On the GAL side of partisan mobilization, Norway seems an unlikely candidate for strong crystallization of a globalization cleavage too, beyond the issue of immigration. The radical left party is pro-immigration but anti-EU (see Jupskås and Langsæther, Reference Jupskås, Langsæther, March, Escalona and Vieiraforthcoming). The green party is not as outspokenly pro-European as other GAL parties in Europe (NTB 2021). It is the mainstream parties that support EU membership in Norway, but they rarely put the topic on the political agenda for various reasons, including internal conflict over the issue as well as electoral strategies, as the Norwegian population has been massively opposed to EU membership since the Great Recession (cf. Aardal et al., Reference Aardal, Bergh and Aardal2019: 78).

Since we expect positions along the four bones of contention to become increasingly coherent due to the politicization of globalization-related issues, we expect there to be more such coherence in the UK than in Norway.

H6: Relationships specified in H1 to H5 are more pronounced in the UK than in Norway.

Research design, method, and data

To test our hypotheses, we commissioned a survey by YouGov on a representative sample (around 1,000 respondents per country) of the population in Norway and the UK in summer 2020. We operationalize the four bones of contention: permeability of borders, allocation of authority, the normative value of community, and valid justificationsFootnote 1 .

The first ‘bone’ consists of attitudes on globalization-related issues pertaining to the permeability of borders. For immigration, we ask whether immigration enriches cultural life, is good for the economy, is a strain on the welfare system, and makes crime problems worse. We construct an additive index of these four items in Norway (Cronbach’s alpha=.88) and the UK (alpha=.92), transformed to go from 0 (pro-immigration) to 10 (anti-immigration). We further ask questions related to the permeability of borders, whether the respondents think the industry should be better protected through import restrictions, whether human rights should be upheld across the globe, even if it requires military intervention, and whether jobs and economic growth are more important than combating global climate change. These are measured through five-point Likert scales from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Finally, we ask respondents about the desired form of relationship between their country and the EU ranging from complete independence to full membership. We dichotomize this variable so that it captures support for or opposition against EU membership. We measure cosmopolitan–communitarian priorities by asking respondents which two items they would like society to emphasize to face major global challenges. They may choose between several items, and we have constructed dummies taking on the value 1 for the ones they mention and 0 if the respondent did not mention each item. Priorities may stem from partisan cueing. GAL parties are likely to cue their cosmopolitan followers on the importance of individuals’ rights, in the form of the right to a clean and safe environment and to move across country borders. TAN parties, on the other hand, are more likely to cue the importance of collective needs, including traditions; national defence; and empowering the prime minister (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe2002).

The second ‘bone’ concerns international authority: to what extent should inter- and supranational institutions like the UN and EU be empowered to decide on a range of policy issues? We ask respondents whether the UN, the EU, national governments, NGOs, or commercial enterprises should decide on policies on international peacekeeping, protection of the environment, aid to developing countries, refugees, human rights, and infectious diseases. We construct an index by giving respondents 1 point for each policy area they want the UN or EU to be responsible for, 0 points for NGOs, private actors or don’t know, and −1 point for choosing national government. The scale then goes from +6 for someone who wants the UN or EU to be in charge of all policy areas, to −6 for someone who wants their national government to be in charge of all policy areas.

The third ‘bone of contention’ captures the collective identity, or the relevant community individuals associate with. We measure this by asking the respondents how closely attached they are to their city/town, their county/region/district, their country, Europe, and finally the world, on a scale from very attached to completely detached. The literature on European integration suggests that citizens may identify both with Europe and their nation-state, but it is primarily those with exclusive national identities who are opposed to European integration (e.g., Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2005; Karstens, Reference Karstens2020; Moland, Reference Moland2021). While dichotomous variables are often employed, we argue that these identities can be more or less exclusive. As we are not only concerned with European integration, and cosmopolitan–communitarian identities are broader than only the nation versus Europe, we create a scale of cosmopolitan–communitarian attachments by subtracting the average score on Europe and the world from the average score on city, region, and nation. The scale then goes from −4 for someone who is very attached to Europe and the world and completely detached from their city, region, and nation, to +4 for someone who is very attached to their city, region, and nation and completely detached from Europe and the world. Citizens who show both a strong international and national/local identity will have values close to the midpoint of the scale. Higher values thus indicate more exclusive communitarian identities, while lower values indicate more exclusive cosmopolitan ones.

The fourth ‘bone of contention’ captures justifications or the invocation of moral, ethical, and instrumental values to base preferences regarding permeability of borders. We include a question aimed at tapping the relative importance respondents ascribe to majoritarian vs liberal components of liberal democracy. Respondents are asked to rank four components of democracy from most to least important: The people decide; my rights are protected by the law; no one is above the law; and we are free to express our opinions. The first is an operationalization of collective self-determination, the second and third of protection of individual liberties and the fourth may be considered relevant to both the liberal and democratic pillars of liberal democracy. It here functions as a baseline.

To test the hypothesis that communitarians attach greater weight to courage than cosmopolitans, we asked respondents to rank order courage, generosity, honesty, humor, and self-control from most to least important virtue. A long-standing debate in public opinion research shows that ranking variables are often demanding on the respondent, hard to administer and susceptible to negativity bias due to their ipsative nature: the ranking of one item constrains the subsequent ranks of the remaining items (Hino and Imai, Reference Hino and Imai2019, s. 369). Negativity bias is mainly a problem when the analysis involves a latent construct measurement such as factor analysis (Hino and Imai, Reference Hino and Imai2019). We do not employ such an analysis. The main remaining problem is using rank ordered items as ordered categorical data. This can potentially lead to overfit in a predictive model (Gertheiss and Tutz, Reference Gertheiss and Tutz2009). For both the democracy components and the virtues, we therefore create dummy variables coded 1 if the respondent rated the component or virtue in question highest, and 0 otherwise.

Finally, we consider to what extent the normative component is related to the organizational component in the two countries, that is, to what extent these attitudes and values are related to party preference. We ask respondents how probable it is that they would ever vote for each party on a scale from 1 (certainly never) to 10 (certainly sometime in the future). This is a standard propensity to vote (PTV) variable as developed and applied elsewhere (cf. Van der Eijk et al., Reference Van der Eijk2006). Respondents who said that they don’t know were excluded. In Norway we focus on the parties that were above the electoral threshold at the latest election, that is, the Radical Left party SV, the Social Democratic Ap, the Agrarian Sp, the Christian Democratic KrF, the Liberal Venstre, the Conservative Høyre, and finally the Radical Right FrP. In the UK we analyze the respondents’ PTV for the Conservative Party, Labour, the Liberal Democrats, and the Brexit Party.

Findings

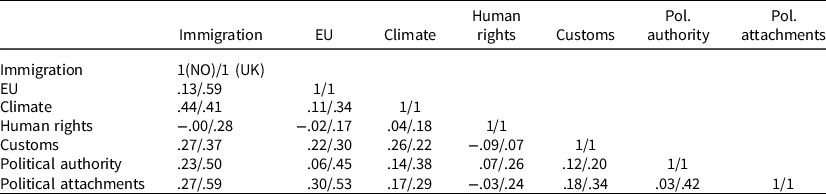

We first test H1, that preferences for open borders are systematically linked to preferences for authority beyond the state. In other words, that people supporting immigration also support EU membership, free trade, etc. –whilst those opposing open borders have similarly consistent preferences across policy fields. We consider here the items measuring cosmopolitan–communitarian preferences as discussed in the data section. As Table 1 documents, these items are much more clearly inter-related in the UK than in Norway, thus lending credence to H6. In fact, the item on global human rights does not correlate substantially with any other items in Norway, whereas there is a moderate correlation in the UK. EU attitudes are weakly correlated to most other globalization attitudes and attachments in Norway, while there is a strong, positive correlation in the UK. Indeed, these seven items could be combined into one rather coherent scale of integration–demarcation preferences in the UK (Cronbach’s alpha = .71) while in Norway they clearly cannot (alpha = .41). A Cronbach’s alpha above 0.7 is usually considered the statistical threshold for a satisfactory scale (see, e.g., Mehmetoglu and Jakobsen Reference Mehmetoglu and Jakobsen2017: 282). By comparison, and to provide a benchmark, scales of economic left-right preferences developed to measure the normative component of the class cleavage have been found to have an internal consistency (alpha) of 0.72 (Bengtsson et al., Reference Bengtsson, Berglund and Oskarson2013). For the education cleavage, an earlier and much-cited attempt at measuring its normative component came up with a scale with an alpha of 0.71 (Stubager, Reference Stubager2008). Finally, for the religious cleavage, scales of preferences related to moral traditionalism (argued to be at the core of its normative component) have Cronbach’s alphas of 0.76 (De Koster and Van der Waal, Reference De Koster and van der Waal2007) to 0.81 (Langsæther, Reference Langsæther2019). In other words, while the integration–demarcation scale in the UK is both statistically acceptable and substantially similar to those of other established cleavages, in Norway it is neither. One may be forgiven for thinking that the results from Norway stem from some sort of Norwegian uniqueness related to its non-EU membership. However, the results here are not only or even primarily due to the EU variable; removing it still yields a Cronbach’s alpha of around .4 for Norway, which means that the internal consistency is unacceptably low, both statistically speaking and compared to established cleavages. In other words, H1 receives support in the UK, but not in Norway, which is consistent with H6.

Table 1. Correlation matrix of cosmopolitan–communitarian attitudes and attachments in Norway and the UK. N = 737 (NO)/804 (UK)

Cronbach’s alpha = .41(NO)/.71(UK). First number in each cell is the correlation in the Norwegian data, second number in each cell is the correlation in the British data.

We now move on to consider to what extent these views are related to citizens’ priorities in terms of global challenges. As discussed, we expect cosmopolitan attitudes and attachments to be related to cosmopolitan priorities such as social equality and solidarity, protecting the environment, and cultural diversity and openness to others. On the other hand, we expect communitarian attitudes and attachments to be more closely related to communitarian priorities, such as traditions, national defense, and empowering the government. We run separate logistic regression models in both countries testing whether this is the case (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1. Binary logistic regression analyses of cosmopolitan and communitarian priorities in Norway.

Significance levels *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. NB! High values = communitarian attitudes. Independent variables have different ranges, so coefficients must be interpreted with that in mind (cf. the data and methods section).

Figure 2. Binary logistic regression analyses of cosmopolitan and communitarian priorities in the UK.

Significance levels *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

Immigration attitudes behave mostly as expected: citizens who are more negative to immigration are less likely to prioritize social equality and solidarity and cultural diversity, while they are more likely to prioritize traditions, national defense, and (only in the UK) empowering the PM, controlling for the other attitudes. However, they are no less likely to prioritize protecting the environment, when controlling for their attitudes to combating climate change.

Similarly, people who are more in favor of economic growth than of combating climate change are much less likely to prioritize protecting the environment, and more likely to prioritize national defense and (only in the UK), traditions. In the UK alone, people who are more opposed to moving political authority to the international level are also less keen on prioritizing climate change. However, the remaining attitudes are not related to priorities about global challenges in either country, when controlling for the other attitudes.

However, it is important to remember that in the UK, contrary to Norway, these items are highly correlated with each other (although not to the extent of inducing serious multicollinearity issues; VIF values range from 1.2 for customs to 2.10, for immigration and tolerance from .83 to .48). This makes it harder to tease out the independent effect of the various items. We also ran separate binary logistic regression models including the items one by one in both countries. For the British case, more communitarian attitudes, allocations of authority, and conceptions of communities individually predict a higher priority of traditions, national defense, and empowering the PM, while cosmopolitanism is associated with a higher priority of social equality, environmental protection, and cultural diversity. All coefficients are also statistically significant apart from the effect of customs, on environmental protection and empowering the PM. To not overwhelm the reader with tables, we report here only the results for the EU variable (in Table 2), while the remaining models are available in the online appendix (see individual Tables A.6.1–A.6.7 for Norway and Tables A.6.9–A.6.14 for the UK).

Table 2. EU attitudes and cosmopolitan–communitarian priorities in Norway and the UK

Significance levels *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

A different picture emerges in Norway. Coefficients are generally smaller than in the UK, many of them are not statistically significant, and some are in the opposite direction of what we expect. Results are the most different for EU attitudes (cf. Table 2). While people who oppose EU membership in the UK are much more likely to oppose the cosmopolitan priorities and support the communitarian ones, in Norway there is no statistically significant relationship with any of the priorities except traditions. There is thus evidence in favor of H2 in the UK, but not in Norway. The normative component of the globalization cleavage is more crystallized among the British public than among the Norwegian one, supporting H6. There is strong evidence of crystallization of policy attitudes in the UK. Evidence of connected values and priorities is decidedly weaker.

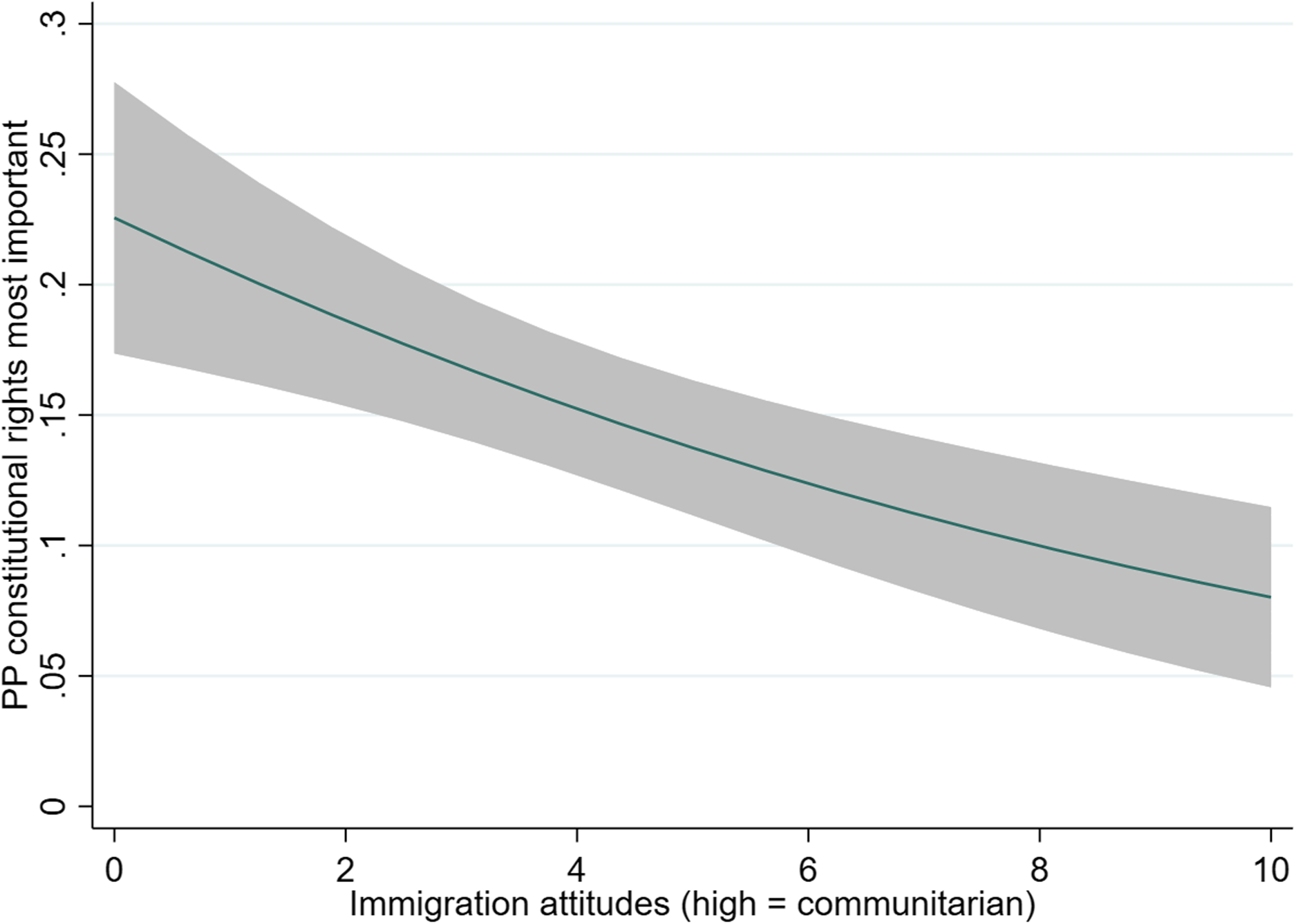

We now turn our attention to H3 to test the relationship between cosmopolitan–communitarian attitudes and citizens’ conception of democracy. As iterated in the theory section, our expectation is that people with stronger communitarian attitudes emphasize collective self-determination aspects of democracy (i.e., democracy is the enactment of the people’s will) while cosmopolitans prioritize the rule of law (i.e., constitutional rights) and equality before the law (i.e., no-one is above the law). We do not find support for these expectations in the models including all items simultaneously (see Tables A.7.1–A.7.2 in the appendix). However, as discussed for societal priorities, the items are highly correlated with each other, notably in the UK. Also, as units missing on any of the variables are excluded, we lose statistical power. We therefore, as for societal priorities, present bivariate analyses in appendix tables A.7.3–A.7.9 (for Norway) and for the UK they are presented in tables A.7.10–A.7.16.

Our results from these analyses for Norway are only weakly in line with H3. Those who prefer demarcation of national borders are less likely to rank equality before the law as the central tenet of democracy. We observe that only climate attitudes, immigration concerns, and political attachments show acceptable statistical significance in predicting rule of law and equality before the law.

The results for the UK, however, support H3 to an extent. In line with expectations, citizens with stronger communitarian attitudes are more likely to prioritize self-determination and are rather unlikely to prioritize constitutional rights as the most important element of democracy (Figure 3). These trends are more pronounced when it comes to communitarian attitudes toward issues of immigration, EU membership, and political attachments, while less so for communitarian preferences regarding allocation of political authority, flow of goods and services across borders, and human rights. Moreover, the observed pattern between communitarian preferences regarding immigration, EU membership, and political attachments are statistically significant at 0.05 level.

Figure 3. Immigration attitudes and predicted probability of reporting constitutional rights as most important component of democracy in the UK.

The difference in results for the two countries can be interpreted as a sign of different degrees of crystallization of the globalization cleavage in the UK and Norway. As mentioned in the theory section, the recent Brexit debate in the UK may have catalyzed the crystallization of the cleavage by compounding such issues. Thus, the results also lend credence to H6 to a certain extent.

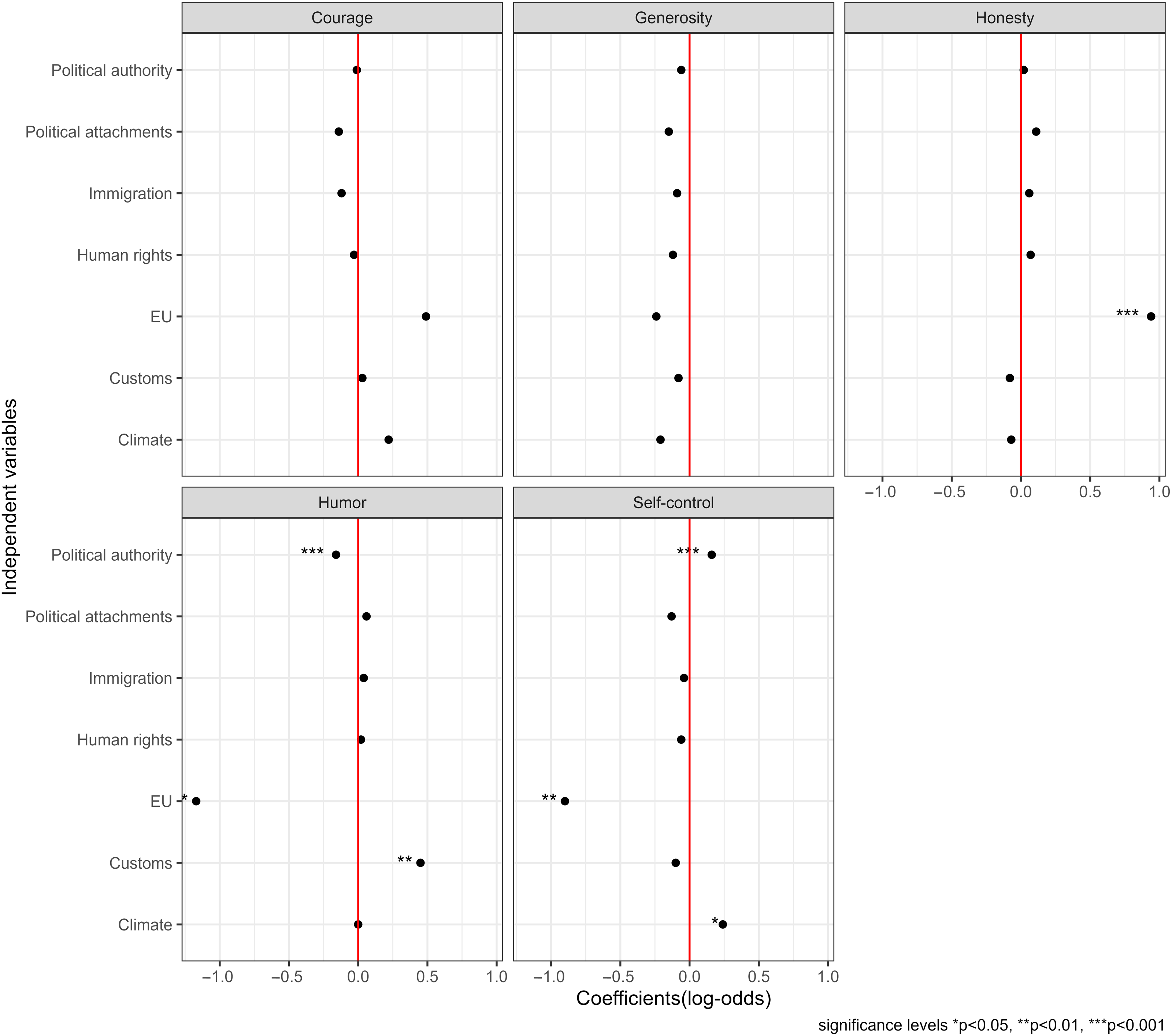

We now move on to test H4 – to what extent are cosmopolitan–communitarian preferences related to deep-seated ideas about virtues? Contrary to expectations, prioritizing courage as a virtue is not related to communitarian preferences, as Figures 4–5 illustrate. We do, in fact, find very few systematic associations between virtue preferences and indicators of the first three bones of contention. However, interestingly, opponents to the EU in both Norway and Britain tend to prioritize honesty as a virtue, while supporters prioritize self-control. There may thus still be a nascent relationship between virtues and the conflict between cosmopolitans and communitarians, albeit not the one MacIntyre envisioned.

Figure 4. Binary logistic regression analyses of virtues in Norway.

Significance levels *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

Figure 5. Binary logistic regression analyses of virtues in the UK.

Significance levels *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

We now move on to the final part, where we consider to what extent the normative component is translated into the organizational component in the two countries. That is, to what extent these attitudes, attachments, and communities are related to party preference.

As shown in Figure 6, immigration attitudes are strongly related to party preference in Norway; full regression results are reported in Appendix table A.8.3.1. Being opposed to immigration predicts less support for the radical left SV, the social democratic Ap, and to a lesser extent the liberal Venstre and the Christian Democratic KrF. There is no relationship (after controlling for all the other attitudes) to the Agrarian Sp, nor to the Conservative party Høyre, while it strongly and positively predicts support for the radical right FrP. Opposition to EU membership reduces the likelihood of supporting KrF, Venstre, and Høyre, but has no clear relationship with support for the other parties.Footnote 2 Prioritizing growth over climate change is associated with reduced support for SV (which is also an environmentalist party), and increased support for Høyre and FrP. Supporting global human rights does not correlate with support for any party. A preference for customs to protect national industry is related to SV, Ap, and – most strongly Sp support, while negatively associated with supporting Høyre. Finally, the political authority and attachments variables are not related to any party support, except for Venstre. Those who prefer a more national approach are less likely to support it. Overall, cosmopolitanism versus communitarianism explains 6–31% of the PTV for the different parties, with the strongest explanatory power for the radical left (25%) and the radical right (31%). For the two largest parties, cosmopolitanism–communitarianism can only explain 12% of Ap support and a meager 7% of Høyre support.

Figure 6. OLS analyses of party preference (propensity to vote for each party) in Norway.

Significance levels *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

Moving on to the UK, immigration opposition is negatively related to LibDem and Labour support, while positively related to Conservative and Brexit Party support, as one would expect (see Figure 7 and Appendix Table A8.3.2). Contrary to the Norwegian case, EU attitudes are strongly predicting support for all the parties, although perhaps surprisingly less for the Brexit party than for the other parties.Footnote 3 Climate attitudes are only related to support for the Conservatives, where those who prioritize economic growth are more likely to be Conservative. Human rights and customs attitudes are not related to party support at all in the UK (controlled for all the other variables), while those who prefer national political authority are less likely to support Labor. Finally, those with more communitarian attachments are less likely to support the Liberal Democrats and the Conservatives and more likely to support the Conservatives.

Figure 7. OLS analyses of party preference (propensity to vote for each party) in the UK.

Significance levels *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

While there is support for H5 in both countries, cosmopolitanism–communitarianism has much more explanatory power for party preference in the UK than in Norway, supporting H6. For no party in the UK is it below 30%, and importantly, we can explain more than 40% of the variation in support for the two major parties in the UK with these attitudes. Also, in the UK most of the associations are soaked up by EU and immigration attitudes, while in Norway they are more varied and depend on the party in question.Footnote 4

Conclusion

Globalization-related issues like immigration and European integration are fiercely contested. They are salient in many European countries; people have strong sentiments about them, and political parties mobilize both supporters and opponents. At the same time, the question remains to what extent these conflicts have crystallized into a political cleavage; one that can fold new issues into existing conflict patterns and thus might structure party competition for years to come. While considerable research has been done on the structural determinants of citizens’ voting preferences and on party ideologies, comparatively little attention has been paid to the normative component of the globalization cleavage at the individual level, beyond attitudes toward immigration and EU integration. We note that cleavage literature in general – and globalization cleavage literature in particular – has spent more resources investigating the structural and organizational component. This paper contributes to the challenge of analyzing the depth of the normative component. We do this through a novel cross-sectional comparative survey in Norway and the UK with innovative items to tap priorities, values, understandings of democracy and virtues that are informed by cosmopolitan and communitarian political thought. We developed new questions on values, understandings of democracy and virtues. This leads to one expected finding: that cosmopolitans consider constitutional rights to be a more important element of democracy than communitarians do in settings where the cleavage is at least somewhat crystallized. It also leads to unexpected findings: that opponents to the EU prioritize the virtue of honesty while supporters prioritize self-control. Finally, it leads to some null findings. Particularly that we have no evidence to support the notion that communitarians value the Aristotelian virtue of courage higher than cosmopolitans do. Future research could further explore the existence of the normative dimension of the globalization cleavage by trying out our items in different contexts, building further on Schwartz values, or developing other ways of analyzing the normative component. This normative component of cleavages at the individual level deserves more scholarly attention than it has received so far.

Our comparative design aims to leverage the effect of the Brexit referendum as a critical juncture on the crystallization of the globalization cleavage. While Brexit has strongly politicized EU membership in the UK, the EU is effectively depoliticized in Norway through the EEA agreement and ‘gag rules’ by coalition parties to downplay it. We therefore consider these two countries to be most likely and least likely cases respectively concerning the crystallization of the globalization cleavage. Our findings show that there is significant correlation in attitudes toward different globalization-related issues in the UK, mirroring findings from Germany (Mader et al., Reference Mader2020), although the internal associations are weaker than one would have expected from a fully crystallized cleavage over globalization in a country where the issue has been extremely salient in recent years. There is no similar connection in Norway. Our investigation goes beyond the usual suspects of immigration and EU membership, to include climate change and trade, views about political authority, and political attachments and identities. We have used the identity items in our survey to generate a single continuum, ranging from exclusive cosmopolitan to exclusive communitarian identity. This fits with our theoretical approach of measuring crystallization, but we acknowledge that other measures exist in the literature and urge future research to apply alternative measures. We show that immigration attitudes are a strong predictor of party choice, linking the normative to the organizational component of the new cleavage. This is more strongly the case in the UK than in Norway. In terms of external validity, we expect the potential crystallization of the globalization cleavage to depend on the politicization and framing of globalization-related issues. In countries where globalization-related issues are highly salient and prominent in public debates, where political polarization on the issues is pronounced, and where political actors link the various issues to each other in political discourse, we think results similar to those we found in the UK are likely. On the other hand, where globalization-related issues are not very salient, political polarization on such issues is relatively low, and political actors do not link these issues, we think it is more likely to find results similar to those in Norway. To what extent this is the case in different countries must of course be assessed in detail in future studies.

Our study comes with limitations. First, a single-shot cross-sectional survey with two countries means we rely on observational data. While we have good reasons to believe that Brexit can account for a number of the observed differences between the UK and Norway reported here, we cannot prove a causal link. There are many more differences between the UK and Norway, such as the electoral system, income inequality, colonial history, and so on, that might have an influence. The choice of cases was deliberate, in terms of recent political events. Yet, we are never fully able to control all possible explanatory factors in a limited comparative design with real-existing cases. The lack of normative crystallization in Norway could potentially be a result of its unique relationship with the EU. We argue, however, that this is unlikely to be the case. First, because other attitudes related to the permeability of borders are also unrelated to each other in Norway – the results do not hinge upon the inclusion of EU attitudes. Second, because even in the most likely case of post-Brexit Britain, crystallization of the normative component is surprisingly limited. In the logic of our paired comparison research design, we expect other European countries to lie somewhere in between these two extremes.

Notwithstanding those limitations, our main conclusion is that there is little evidence to support the notion of a more thorough crystallization of the normative component of the cleavage beyond attitudes. As it turns out, attitudes are only weakly connected to values and hardly at all to virtue perceptions. We thus conclude that the normative component of the new globalization cleavage is not crystallized in Norway, and not fully crystallized even in the extremely politicized context of the UK. These findings imply that the new globalization cleavage remains malleable, depending on political contexts and the behavior of political actors. This is in line with evidence from the class cleavage and religious cleavage (e.g., Evans and de Graaf, Reference Evans and de Graaf2013; Langsæther, Reference Langsæther2019). There is thus no reason to believe that further crystallization of the globalization cleavage will follow automatically in the time to come: it depends on partly exogenous events (refugee crises, EU integration crises, etc.) and the politicization and linking of issues by political actors. This is good news for those who are averse to culture wars, as it opens the possibility that the influence of globalization conflict can weaken in the UK if the political agenda is directed away from immigration and EU membership. At the same time, malleability means that the globalization could be further crystallized by culture warriors, for example via another public EU debate.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773922000534.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the NTNU research group on Elections, Values and Political Communication (EVPOC), 21 May 2021. We would like to thank Elena Baro and Anders Todal Jenssen for very valuable comments.