Introduction

The Korean peninsula is one of the world's most volatile areas. Decades after the collapse of the Berlin Wall Korea remains caught in a dangerous Cold War stalemate. The spectre of war is never far removed. The latest crises emerged in 2017 when North Korea's renewed nuclear ambitions triggered an equally aggressive response from the United States. President Donald Trump publicly vowed to ‘totally destroy’ North Korea.Footnote 1 The situation was subsequently diffused but the conflict is far from solved. Such crisis-detent cycles have taken place many times before without substantial changes to the dangerous security dilemmas that drive them.

The purpose of this article is to use visual autoethnography as a way of rethinking the security situation in Korea. I draw on my experiences of working in the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), where I was stationed as a Swiss Army officer between 1986 and 1988. I employ my own photographs to examine how an appreciation of everyday aesthetic sensibilities can open up new ways of thinking about security dilemmas. In this sense my article is more about the potentials and limits of visual autoethnography than about the situation in Korea. There is no way I can possibly offer either a comprehensive take on the security situation or an account of recent developments. I inevitably have to leave out many important issues. But I want to flag that when selecting the issues to be examined I drew on over thirty years of experience with and research on Korea.Footnote 2

The questions I ask are: what exactly can visual autoethnography add that cannot – or not easily – be revealed through other forms of inquiry? How can my own experiences and photographs possibly be political relevant, all the more since they go back more than three decades?

The key argument I advance is a conceptual one: that visual autoethnography can be insightful not because it offers better or even authentic views – it cannot – but because it has the potential to reveal how prevailing political discourses and practices are so entrenched that we no longer see their partial, political, and often problematic nature.

After introducing visual autoethnography and providing a brief background on the Korean conflict and my work experience in the DMZ, I provide two empirical illustrations of how aesthetic sensibilities developed from everyday visual experiences can provide us with an alternative understanding of both the sources of conflict and the search for solutions.

First: I show how a self-reflective engagement with my own photographs of the DMZ reveals the deeply entrenched role of militarised masculinities that transgress the border and shape security policies on both sides. When I first took my photographs three decades ago, I noticed everything about the DMZ, except its striking gendered nature. As a military officer, and having growing up in a patriarchal society, the discourse of militarised masculinity was so omnipresent and naturalised that I simply accepted it at face value: as how things were meant to be, particularly in the DMZ. A self-critical look at my own positionality, and my changing relationship to my own photographs over a period of three decades, reveals the power of dominant security discourses to disguise their origin and effect.

Second: I reflect on my photographs of everyday life in North Korea. I show how and why it is impossible to see the Korean conflict in neutral ways. Drawing on my positionality and photographs I then reveal a reality that is different from both prevailing political discourses on the peninsula: that of North Korea's glorification of life in a communist paradise; and that of the South Korean and the Western world, which depicts the North as a grim and authoritarian state, solely responsible for the recurring nuclear crises that destabilise the region. I do not deny the massive human rights abuses that take place in the North or trivialise Pyongyang's nuclear programme. Nor do I claim that my photographs offer an authentic or even particularly unique view. What they do highlight, though, is a positionality that reveals how security discourses about North Korea are always partial and have as much to do with who is viewing – and securing – than what is being seen and secured.

In a final part of the article I reflect on both the potential and limits of visual autoethnography as form of inquiry and on the larger implications for the study of politics and security. Taking seriously questions of positionality and how we see and experience the world around us is to acknowledge the interconnected and contingent nature of politics. In the context of Korea, this would entail questioning the prevailing militarised and black-and-white approaches to security policies, which see North Korea as a threat that can only be contained with military force and economic sanctions. To recognise and engage our own bias and complicity – as individuals and collectives – is to question and revaluate the role various actors played in constituting the complex security dilemmas that haunt the peninsula. These insights go far beyond the Korean case because they show how visual autoethnography has the potential to open up innovative solutions to political problems that otherwise remain so entrenched that they often are not even recognised as such.

The nature and power of visual autoethnography

When developing insights from my experience and photographs I explicitly draw on a tradition of autoethnographic research that explores how the experience of the ‘self’ can provide legitimate and systematic scholarly insights. Key contributions here come from a range of different theoretical orientations – feminist, postcolonial, poststructural, or constructivist – but all show how concrete and often policy-relevant insights can emerge from exploring lived experience, be it as a diplomat, refugee, or policy analyst.Footnote 3

One of the key challenges of autoethnographic research is to avoid self-indulgence. My own experiences matter – and should appear here – only insofar as they directly illuminate the political issues at stake.Footnote 4 In this sense, my analysis is not about my own person but about how my experiences and my positionality shed light on political issues in new ways. In pursuing this line of inquiry I draw on feminist research, which has for long argued that positionality is key to rethinking the power structures of international politics.Footnote 5 Some of the most innovative contributions in this realm have been those of Cynthia Enloe. In a series of influential books she has shown how listening to voices from everyday people – in her studies of women at the margins of society – can circumvent entrenched scholarly conventions and reveal power relations that are at the core of how politics is carried out.Footnote 6

Autoethnography is part of a larger scholarly movement that seeks to validate and explore the significance of everyday experience for the study of international relations. Liam Stanley and Richard Jackson, for instance, advance a critique of ‘methodological elitism’ to call for an appreciation of the politics of everyday narratives. But rather than exploring the everyday as ‘a site of practice’ where ‘actors exercise agency’,Footnote 7 I am more interested in the epistemological lessons of the everyday, at what Linda Åhäll called ‘being as a mode of knowing’.Footnote 8

I am taking autoethnography a step further and propose a form of inquiry based on reflections about my own photographs. I call this form of inquiry ‘visual autoethnography’. I draw on photographs I took while working in the Korean DMZ and travelling back and forth between South and North Korea. I acknowledge that these experiences involve a range of sensory perceptions, not just visual ones, but also hearing, touching, smelling, feeling. Neuroscientific studies show that these sensory perceptions are intertwined, so much so that the brain processes ‘perceptual information in much the same way, no matter which organ delivers it’.Footnote 9

I am particularly inspired by a new generation of International Relations scholars who have embarked on creative ways of understanding the links between lived experiences, images, and the political. Consider how Saara Särmä uses a ‘playful visual method’, in her case Internet parody images that challenge commonsensical assumptions about nuclear politics.Footnote 10 Or look at how Leena Vastapuu uses a method that she calls ‘auto-photography’ to observe what becomes visualised when she provides former Liberian girl soldiers, now living in the urban slums of Monrovia, with cameras to document their lives. We then see not only threats that tend to be invisible to Western researchers, but also particular security structures, such as those linked to social networks.Footnote 11

Visual autoethnography has obvious parallels but is also distinct from a range of similar methods, such as ‘visual ethnography’,Footnote 12 ‘photo-elicitation’,Footnote 13 and ‘participatory photography’.Footnote 14 The key distinction here is, of course, that the focus lies on examining the political relevance of my experience though my own photographs.

I was often asked to elaborate on why I took my photographs; how they differ from tourist ‘pics’ or media coverage of the DMZ; what constraints I encountered; and how I selected the photographs for publication. These questions reach across all aspect of autoethnographic work: pre-, in- and post-field, as Cecilie Basberg Neumann and Iver Neumann put it.Footnote 15 They deal with my background, my experiences, and the process through which I subsequently make sense of them. On some level, answering these questions is fairly straightforward. I have always been a passionate photographer, so when I took up my job in the DMZ in 1986 I inevitably had a camera with me – a Minolta with three prime lenses. I simply followed my passion and photographed everything I saw and found interesting, not just in the DMZ and in North and South Korea, but also in China and Japan. As a Swiss Army officer with diplomatic status I was relatively free to photograph what I saw, even in North Korea, but faced restrictions with regard to certain military installations. I never intended to offer a systematic visual documentation and I never envisaged that I would write about my experience or display my photographs. This is why I did not note down the location and exact time of each photograph. I took hundreds of them and I can only reproduce a handful here, though re-viewing them decades later formed an important base for my autoethnographic reflections.

The more important point is: it does not really matter – epistemologically – why I took my photographs, how I selected and framed my views or even how I ended up choosing a few out of several hundred for display. I am not claiming to offer systematic visual insights into the DMZ and the Korean conflict. I am not trying to visualise some kind of authentic experience that either tourist photographs or media depictions fail to deliver.

Rather than being authentic or representative, I use my photographs as tools to re-view, re-evaluate and re-imagine the world. If they are representative, then only of my positionality and of how self-reflective ruminations about this positionality can reveal existing political discourses and the power relationships they embody. In this sense, my photographs illustrate the situatedness of knowledge and, in doing so, are illustrations that stand in a conversation with the text that surrounds them.

Visual autoethnography is a form of ‘seeing as a way of knowing’, as Joan W. Scott puts it.Footnote 16 Perhaps my photographs can offer new evidence and alternative insights into political issues. But experiences, including visual ones, are never free of values. They are inevitably contestable. They are always already interpretations that also need to be interpreted. Visualisations of the world are as much about us as seers than the phenomena we seek to depict. This is why I try to be self-reflective about how my experiences and visual documentations of them are part of the very social-political constellations I analyse and critique.

Visual autoethnography is, in short, an ongoing reflective process that uses positionality to reveal the often arbitrary but largely concealed construction of political discourses and practices.

Inside the DMZ: Seeing and witnessing border politics

Before I begin my autoethnographic inquiries into security discourses on the Korean peninsula some background information is necessary.

The division of the Korean peninsula goes back to the Japanese occupation of the peninsula and the events of the Second World War. In the process of dismantling the Japanese colonial empire, American and Soviet troops occupied the peninsula, dividing it into two parts along the 38th parallel. Separate political regimes were established on each side, reflecting the ideological standpoints of the two superpowers. What happened between then and the outbreak of the Korean War is much debated. Less debatable is the far-reaching impact of the war itself. It started as a civil war but then involved two great powers on opposing sides: first the United States, which intervened, together with other nations through a UN mandate designed to roll back the northern occupation of the South; and then China, whose involvement saved the North from defeat and secured a military stalemate along the original dividing line at the 38th parallel. In 1953 an Armistice Agreement ended three years of intense fighting, which killed more than a million people. But the memory of violence and death continues to dominate politics on the peninsula. More than half a century later Korea remains hermetically divided between a Communist North and a Capitalist South: caught in a tense and anachronistic Cold War stalemate.

The DMZ lies at the physical and symbolic centre of the Korean conflict. It is a buffer zone along the 38th parallel that keeps the two warring sides apart. It is approximately four kilometres wide and 250 kilometres long. Up to two million troops face each other across the border, and so do plenty of weapons of mass destruction. Tensions are a permanent feature of the DMZ and can escalate any time. The DMZ is often depicted as ‘the scariest place on Earth’, as former US President Bill Clinton once put it.Footnote 17

The DMZ is also a highly symbolic marker of the conflict and, as such, both represents and influences political dynamics. Press coverage of the conflict is often accompanied by photographs or films of the DMZ. But very few people have actually seen and experienced the DMZ, for it is largely off limit to civilians on both sides. There are tourist trips to the DMZ but they are limited, tightly controlled, and carefully staged. As a result, and as Suk-Young Kim points out, ‘most Koreans encounter the DMZ not as an actual physical space, but through mediated images: photographs, films and videos’.Footnote 18

The DMZ, then, is as much a visual phenomenon as it is a physical one. Images of the DMZ, and the Korean conflict in general, shape how security issues on the peninsula are represented, perceived, and publicly debated. Images delineate what we can see and what not and, in doing so, inevitably frame how political issues are either highlighted and discussed or ignored and dismissed. The political consequences of these dynamics are particularly important since images – both still and moving ones – provide us with the illusion that they can deliver authentic and neutral insights. It is this seductive ability to make us believe that what we see is real that provides images with an enormous amount of power to influence political dynamics on the Korean peninsula.Footnote 19

A unique place in the DMZ is occupied by the so-called Joint Security Area (JSA) in the border village of Panmunjom. It is the location where the armistice was negotiated and it is the only place in the DMZ where the North and South confront each other face-to-face. The dividing line cuts right through a series of buildings, where occasional meetings are held. Observation posts on either side are permanently guarded in an effort to carefully survey every single move that takes place inside the JSA and across the Dividing Line (Figure 2).

Figure 1. United Nations Command Officer facing Military Demarcation Line (1986–8) © Roland Bleiker.

Figure 2. North Korean officer photographing movements inside the JSA, Panmunjom (1986–8) © Roland Bleiker.

I first arrived in the JSA on a late September day in 1986. In the early hours I was driven from Seoul to Panmunjom, where I took up the position of Chief of Office of the Swiss Delegation to the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission (NNSC). ‘Keep up the fire’, bellowed a young US soldier as we crossed a bridge over the Imjin river and approached the most militarised landscape I had ever seen: the so-called Demilitarized Zone. My new home turned out to be even more surreal: located right at the barbed wire fence that divided the peninsula, our barracks were surrounded by military observation posts and loudspeakers on both sides. The latter were competing with each other every night, blaring propaganda speeches and music into an otherwise pristine and stunningly beautiful landscape.

The commission I worked in for two years, the NNSC, was established with the Armistice Agreement in July 1953. It was meant to supervise two clauses in the Agreement that prohibited the introduction of new military personnel and weapons. The Commission's neutrality consisted of each side choosing two nations that did not actively participate in the war. The North opted for Czechoslovakia and Poland. Switzerland and Sweden were selected by the South, formally represented by the United Nations Command. With the intensification of the Cold War the idea of retaining current levels of military personnel and equipment became a farce. With its official purpose gone, the NNSC radically shrunk. By the time I arrived, in 1986, the Swiss Delegation consisted of only six people and its actual purpose was informal: to establish links across the DMZ at a time when there were few meaningful interactions between North and South (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The author (far right) with other members of the NNSC in Man'gyŏngdae, Kim Il-sung's alleged birthplace in North Korea (1986–8) © Roland Bleiker.

Being able to cross the otherwise hermetically sealed DMZ and travel back and forth between North and South was a rare privilege. At the time, the NNSC members were among the very few able to do so. Even today, the DMZ remains tightly sealed, so much so that crossing over to the other side is still, as Kim Suk-Young points out, ‘a high-stakes performative act’.Footnote 20

Border politics: From the division of space to the delineation of thought

The obvious starting point is the border itself. Arriving in the DMZ triggered in me two seemingly contradictory initial impressions, which I would like to flag as a preliminary point in my visual autoethnographic analysis.

First is the visual encounter with one of the world's most guarded and hostile borders. Marked by barbed wire and surrounded by propaganda loudspeakers and military personnel on both sides, the Military Demarcation Line is perhaps the world's most closely controlled border. It is the line that divides North and South. There is virtually no travel and communication across the 38th parallel. For the past half century the Demilitarized Zone has perhaps been a hermetically sealed border. At the time I arrived, in 1986, we two dozen members of the NNSC were among the very few people able to cross the dividing line.

My second impression was that the DMZ is far more complex and multifaceted than a simple border that divides inside and outside, friend and foe. This is, of course, a point that geographers have highlighted for long: that borders are more complex than commonly assumed. They are not ‘simple, homogenous uncomplicated lines’ but often porous and overlapping. They have multiple dimensions and they shapeshift with time.Footnote 21

In the context of Korea it is far more useful to think of borders as an ‘interface’, as introduced and articulated in a compelling way by Valérie Gelézeau, Koen De Ceuster, and Alain Delissen.Footnote 22 For one, the DMZ is not a straight line, but a four-kilometre wide and 250-kilometre long buffer. And it is a stunningly beautiful and pristine nature zone (see Figures 1 and 4). The very militarised nature of the DMZ, and the fact that it is littered with over a million active landmines, means that it is inaccessible to civilians and largely void of people in general. As Kim Suk-Young put it: both Korean states tried to control the DMZ, but neither can. Civilians on both sides tried to cross it, but few can.Footnote 23 Untouched by people for decades, the DMZ has turned into a unique and highly diverse ecosystem that hosts a great number of unique birds and other species, including endangered ones.Footnote 24

Figure 4. Military Demarcation Line, DMZ (1986–8) © Roland Bleiker.

The key point to make here is that the DMZ as a border delineates not only space but also how individuals and societies see, feel, think, and act. It is a boundary that demarcates and shapes collective consciousness. Nevzat Soguk, for instance, stresses that the function of borders often goes beyond ‘fences and walls’ and includes processes through which collective consciousness is shaped and demarcated.Footnote 25 William Callahan, likewise, highlights how walls and borders mark stories about national identities. This is why, he believes, they need to be recognised and studied as ‘multisensory experiences of sight, sound, touch, smell’.Footnote 26

Borders delineate vision and thought as much as they divide space. This is why the DMZ influences what Jacques Rancière calls the ‘distribution of the sensible’: it determines what can be seen and what not. It delineates the boundaries of vision and thought. This process is highly political for politics is, in essence, about how we – as collectives – visualise, speak, hear, and feel about ourselves and others. The distribution of the sensible establishes, for Rancière, what is arbitrarily but self-evidently accepted as thinkable, reasonable, and doable.Footnote 27 It is in this spirit that I now explore how the DMZ as a border space reveals and conceals and what kinds of implications this process has for security politics on the peninsula.

Exposing militarised masculinities through visual self-reflection

The first key autoethnographic insight I would like to highlight has to do with the militarised nature of the so-called demilitarised zone. While the Armistice prevented each side from placing heavy weapons inside the DMZ, they are stationed in very close proximity. And so are 70 per cent of troops on both sides, which it why the DMZ is often called the ‘the most fortified area in the world’.Footnote 28

Militarism cuts right across the hermetically sealed dividing line. Consider, as a visual example, the JSA, where the border runs right through shared buildings and where North and South Korean troops face each other eye-to-eye. Military marching formations and salutes take on an explicitly performative dimension here since they are staged primarily for the other side to see.Footnote 29 Look at the two photographs below: insiders to the conflict can right away see a clash between two antagonistic and completely different worlds, epitomised by North and South, the latter represented by the US-led United Nations Command. But seen from a distance one can see more similarities than differences between these diametrically opposed political enemies. They are all soldiers marching in uniform and performing the same militarised ritual (Figures 5a and 5b).

Figures 5a, 5b. ‘Northern’ and ‘southern’ soldiers in the JSA, Panmunjom (1986–8) © Roland Bleiker.

One key point struck me when I went through my hundreds of photographs of the DMZ: the almost complete absence of women. As a feminist scholar I look at my photographs from back then and I am stunned. There are only men in my photographs. There are South Korean men, North Korean men, Chinese men. There are Czech, Polish, Swedish, and Swiss men. There are American men.Footnote 30

I had a hard time finding any photographs that feature women. One of the few I found was from a Military Armistice Commission meeting (Figure 6). Discontinued in the early 1990s, these meetings took place inside the barracks of the JSA, where the southern and northern side met right across the table. The meetings did not usually amount to more than an exchange of pre-prepared statements in which each side accused the other of violating the Armistice. The meetings too were part of a militaristic performance act and, as a result, were staged to a limited number of military personnel, press, and other observers.

Figure 6. Female soldier/officer outside a meeting of the Military Armistice Commission, JSA, Panmunjom (1986–8) © Roland Bleiker.

The photograph below shows military personnel looking in on the ‘negotiations’, with US (UN Command) soldiers in the foreground and North Koreans in the background. The photograph sticks out because it is one of the very few featuring a woman. She is not looking at the meeting room but across the border to the northern side. I wonder what she thought about as she surveyed this all-male world.

On some level my observations are not surprising. Of course one would expect soldiers in a militarised zone and, of course, one would expect that most of them, if not all, are men.

The surprising observation about this feature, and the significance of visual autoethnography, has to do with my own experience and my changing relationship to the photographs I took over three decades ago.

When I first arrived in the DMZ, in 1986, I noticed everything except the absence of women and the gendered nature of the DMZ. When settling into the JSA and crossing back and forth between South and North I was struck by many things I saw: the stark political differences, the ideological hatred, the cultural diversity but not the most obvious feature: the absence of women. I took this for granted. All the colleagues I worked with in the NNSC were men. All the soldiers and officers I interacted with were men, no matter what side of the dividing line they were located. It seemed normal to me, in part because I was in a military setting, in part because I grew up in a very patriarchal society – Switzerland – where women were only granted the vote when I was 11 years old, with some cantons holding out until well into my adulthood. I was conditioned by the environment I grew up in. I was drafted into the army at 18 and, in an all-male environment, was trained how to march, salute, fire a gun, throw a hand grenade, and drive a tank. I was taught how to execute orders and obey, but not how to think critically, and particularly not about gender issues. Militarised values had been normalised and I accepted them as common sense without questioning – or even being aware – of the political values they entailed.

I now look back in bewilderment at my inability to see the obvious: the highly gendered nature of politics in the DMZ. This is precisely where the links between power and militarisation are at their most effective: in the construction of common sense, in societal discourse that defines what is accepted as normal and not, even if this construction is based on highly partial, exploitative, and problematic foundations.Footnote 31

This is also where visual autoethnography can provide political insights: in self-reflective accounts of our own experiences, including how our own views change in relation to visual representations of these experiences. It is, indeed, the confrontation with visual evidence that, for me, made me realise most acutely how my own positionality reflected political dynamics that were so naturalised for me – and I presume many men around me – that I did not even recognise them. The fact that three decades had passed since I took the photographs adds, rather than subtracts, from the potential of visual autoethnography. It is, in fact, the elapsed period of time that provides the opportunity of insight, for it is the very changing relationship between me and my photographs that reveals the power of discourse to construct and mask power relations.

My experiences, and my relationship with my own photographs, show how and why the political consequences of the gendered and militarised nature of the DMZ go far beyond the immediate and obvious: men in uniforms, surveillance installations, barbed wire. Militarised masculinities are part of broader societal values. They shape collective attitudes and policy formation.Footnote 32 In Korea, they reach far beyond the DMZ. They can be seen, for instance, in clusters of prostitution that pop up around US military bases in the South or in how military personnel interact in a more general way with the civilian population on both sides.Footnote 33 My entire experience in Korea was gendered, revealing what feminist scholars, such as Linda Åhäll, Laura Shepherd, and Annick Wibben have pointed out for long: the need to theorise how militarised masculinities permeate all aspects of society, from the everyday to foreign policies. They are located and gain key political significance in the clothes we wear, the films we watch, the national anthems we rehearse, and the security policies we deem urgent and compelling.Footnote 34

Militaristic ways of thinking become elevated to the prime and seemingly most reasonable and compelling manner to address security issues. The result is that certain individuals, and the values they espouse, are given greater authority to comment on – and take decision about – questions of national security. This hinders both adequate scholarly understanding and the search for innovative policy solutions.Footnote 35

The power to elevate militarism to the most logical and compelling way to understand and solve security issues is particularly pronounced in Korea. Both sides analyse the conflict in strikingly similar militaristic terms, even though they assign blame in diametrically opposing ways. Militaristic values also permeate the search for solutions, to the point where it is difficult to break out of a cycle of violence in which threats and counterthreats produce ever more dangerous standoffs. Solutions to the conflict that are not based on a tough defence posture tend to be dismissed as well intended and naïve at best, ethically problematic and dangerous at worst.Footnote 36 In North Korea there are no overt challenges to this form of militarism, and even in South Korea opposition is difficult. One of the exceptions is the women's movement, which critiques entrenched practices of militarism both within South Korea and in its relationship with the US.Footnote 37 But these and other dissident movements function at the margins of society and have not yet had a substantial influence on military policy and diplomatic negations.

Positionality and the impossibility of neutrality in the Korean Conflict

The key feature of my autoethnographic account that I identified so far – the deeply entrenched form of militarised masculinity – reinforces the very core of the conflict: the juxtaposition of two diametrically opposed and ideologically driven regimes.

The legacy of war continues to dominate not just the DMZ but all aspects of politics and security on the peninsula. Deeply entrenched hatred, born out of death, fear, and longing for revenge, continue to fuel hatred and legitimise aggressive foreign and repressive domestic policies. The absence of face-to-face encounters across the DMZ makes it even easier to construct the other side as evil and inherently antagonistic. Both Korean states have used their power to promote and legitimise their particular worldviews. Through a variety of mechanisms, from ideology-based education to a tightly controlled media environment, both states were highly successful in disseminating a very peculiar form of nationalism that portrays the political system on the opposite side of the divided peninsula as threatening and inherently evil.

This entrenched and deeply emotional antagonism surrounded all of my experiences in the DMZ as well as my travels in North and South Korea. The North is, of course, well known for its colourful and combative public statements. Hatred is channelled, in particular, towards the legacy of Japanese colonialism, the ongoing practice of American ‘imperialism’ and its South Korean ‘puppet regime’. But hatred for the political system on the other side of the border was as pronounced and widespread in the South as in the North.

I will now start to develop a second key autoethnographic insight into the conflict in Korea. I begin with the recognition that it is impossible to understand the conflict in objective ways. Soon after I arrived in the DMZ I became aware that I could not be completely neutral, even though I was meant to be so as a Swiss official and a member of the so-called Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission.

Acknowledging the limits of objectivity might be commonsensical on some level but also runs counter to the fundamental assumptions that drive security policies. Decision-makers and policy advisers commonly stress how their approach to security is based on detached and objective assessments of threats. Consider, just to take one of many examples, a highly influential policy report commissioned by then-US President Bill Clinton. The report advocated an approach North Korea ‘as it is, not as we might wish it to be’. It called for a ‘realist view, a hard-headed understanding of military realities’.Footnote 38

A self-reflective understanding of positionality very much calls into question the notion that security polices can be based on objective understandings of military realities – free of political, cultural, and personal bias.

When I reflect on my experiences I have no choice but to admit that my background made it impossible for me to approach the issue of national division and inter-Korean relations in a neutral manner. I grew up during the Cold War in Western Europe. At that time, everything was black and white: one was either communist or capitalist, red or blue. The iron curtain that divided the US- and the Soviet-led alliance systems established a world in which one could not be neutral. To be so was to show sympathy for the vilified arch enemy and thus to be a potential danger to one's own state and community. My upbringing as well as my mandatory military service reinforced this black-and-white worldview at every point. For instance, when conducting manoeuvres in the tank unit I served, our maps indicated blue flags as friendly troops and red ones as the enemy. Even in the context of the allegedly neutral Swiss defence context, there was no doubt in anyone's mind about which enemy we were getting ready to fight.

Arriving in Korea there was no question for me as to where my allegiances were located. On weekends I was free to leave the DMZ, except when serving as duty officer. I usually went to Seoul, where we Swiss officers had accommodation in the US Army Garrison in Yongsan. Living on a US Army base or travelling in South Korea were all new and very exciting experiences to me, but I always felt I was in ‘my world’, no matter how different it was. I never had this feeling when crossing the border into North Korea, as we did regularly, mostly for trips to Kaesong or Pyongyang. It was to enter a completely different world and this on numerous levels: political, ideological, aesthetic, emotional. It was the world of the ‘other’.

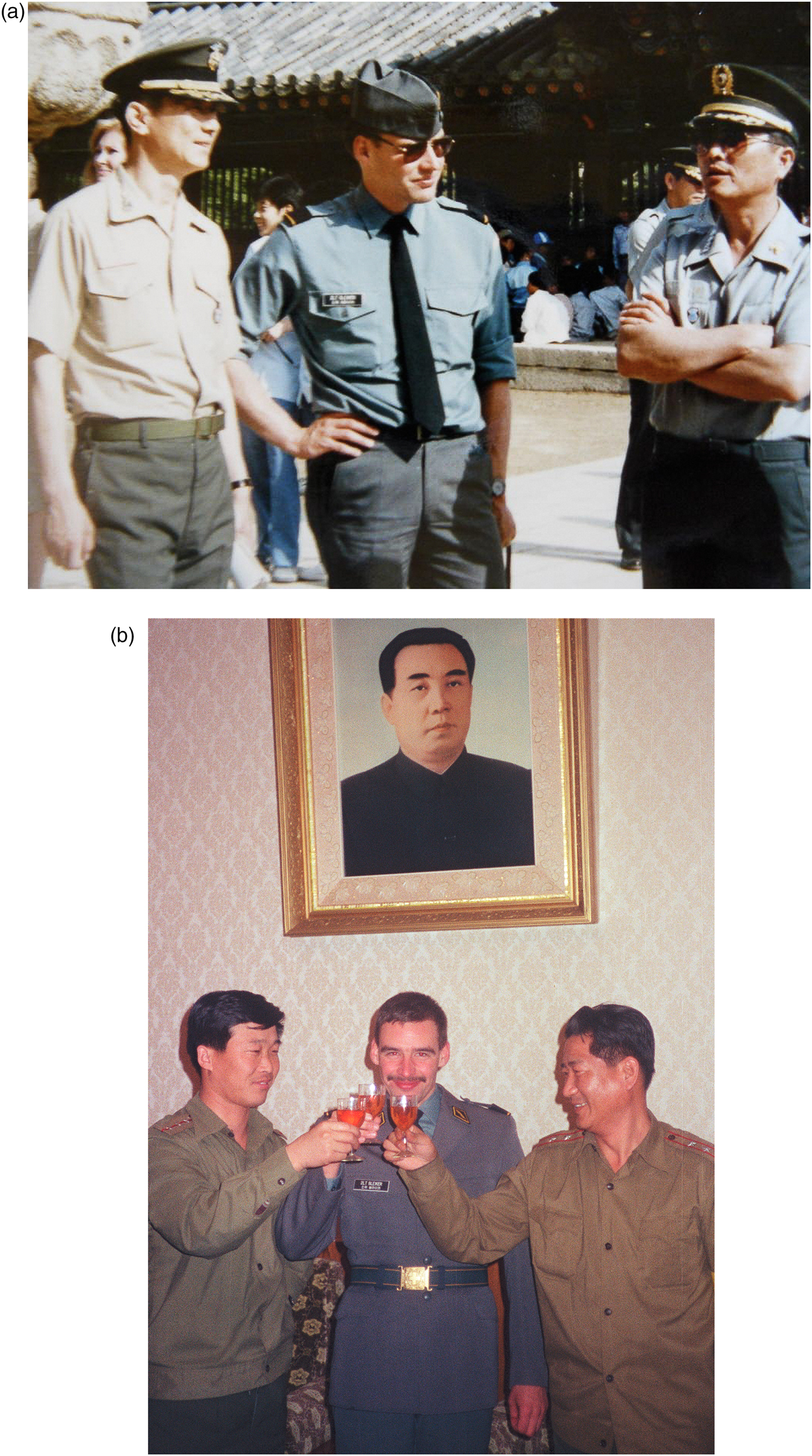

Today I look at the two photographs above (Figures 7a and 7b) from three decades ago and I can see – based on my bodily positions alone – how much more comfortable I felt and behaved when among South Korean officers than when interacting with my North Korean counterparts.

Figures 7. (a) Author with South Korean officers, Seoul (1986–8); (b) Author with North Korean officers, Panmungak, Panmunjom, JSA (1986–8) © Roland Bleiker.

My photographs here serve not only as a way of reliving my own emotional memory but also as visual evidence of an experience that reveals the politics of situatedness. My photographs illustrate how the ideological division on the Korean peninsula, reinforced by the larger dualistic structures of Cold War politics, made it impossible to approach the political issues at stake in a neutral and value-free manner. Mutual antagonisms were running so deep and were so pervasive that it was not possible to step out of their shadows. All this is well illustrated by the prominent feature film JSA, which revolves around a fictional Swiss member of the NNSC who breaks down stereotypes on the peninsula but ultimately realises that she is unable to advance a truly neutral position on the issues at stake.Footnote 39 When faced with an unsolved murder, both North and South allow the fictional Swiss-Korean Sophie Jean to investigate. But, as Youngmin Choe stresses, the neutrality of the Swiss is undermined by the politics of the DMZ and the positions espoused by the key actors. As Choe puts it, Sophie is ‘anything but neutral’, even though she refuses to favour one side over the other: ‘the neutral imperative to stay out of the conflict seems incompatible with the history's dirty hands’.Footnote 40

In short: there is no neutrality in the DMZ. Even just naming ‘Korea’ in the Korean language already involves making a linguistic decision that inevitably associates the speaker with either North or South. The North uses Chosŏn while the South uses Hanguk. Likewise, speaking of North Korea requires, as Shine Choi puts it, to declare ‘whose story of the country should be believed’. The terms for North Korea that the North and South use respectively – Buk-chosun and Bukhan – refer to historical processes and political legitimisations that are incompatible with each other.Footnote 41 As soon as one starts to speak the idea of neutrality vanishes. There is no way to escape ideology, politics, prejudice: the parameters of what can and cannot be said are already circumscribed.

Seeing beyond prevailing narratives: How visual positionality exposes power relationships

If a neutral view of the Korean conflict is impossible the inevitable question is: whose views and political positions have emerged as dominant and what consequences issue from the respective power relationships?

To understand the issues at stake I focus on what is undoubtedly the biggest security challenge in the region: how to understand and deal with North Korea. Pyongyang is the elephant in the room, so to speak: the problem everyone knows about and around which everything revolves. But it also is a problem that we are unable to understand and approach in a neutral and objective manner.

The questions I ask in this section thus are: what are the prevailed visual and political discourses in and about North Korea? What political values are embedded in them? Asking these questions is important because prevailing visualisations inevitably frame our understanding and our approaches to politics and security.

To pre-empt my key point: I want show and argue that my own photographs – and visual autoethnography as a form of inquiry – can reveal the inevitably partial and biased nature of prevailing visual narratives about North Korea. I am not claiming that my photographs offer better or even authentic insights. They cannot. But their positionality can shed light on the power of prevailing discourses to frame and represent political issues, such that it even seems that there is no alternative ‘way out’.

There are two prevailing visual and political narratives about North Korea. I can inevitably only offer a very rudimentary sketch of them here, leaving out a lot of complexities and nuances.

First is the narrative that prevails in North Korea. It is easily summarised: we see a progressive communist country that has emerged out of a struggle against Japanese and American colonialism and successfully managed to establish a thriving society under the leadership of Kim Il-sung and, subsequently, his descendants, Kim Jong-il and, currently, Kim Jong-un. The corresponding visual narrative, embraced and diffused by North Korean media, is one that glorifies the leadership and highlights the struggle against imperialism and the march towards economic and political progress. A strong defence posture, backed up with the ambition to develop a credible nuclear deterrent, is an essential part of this narrative.

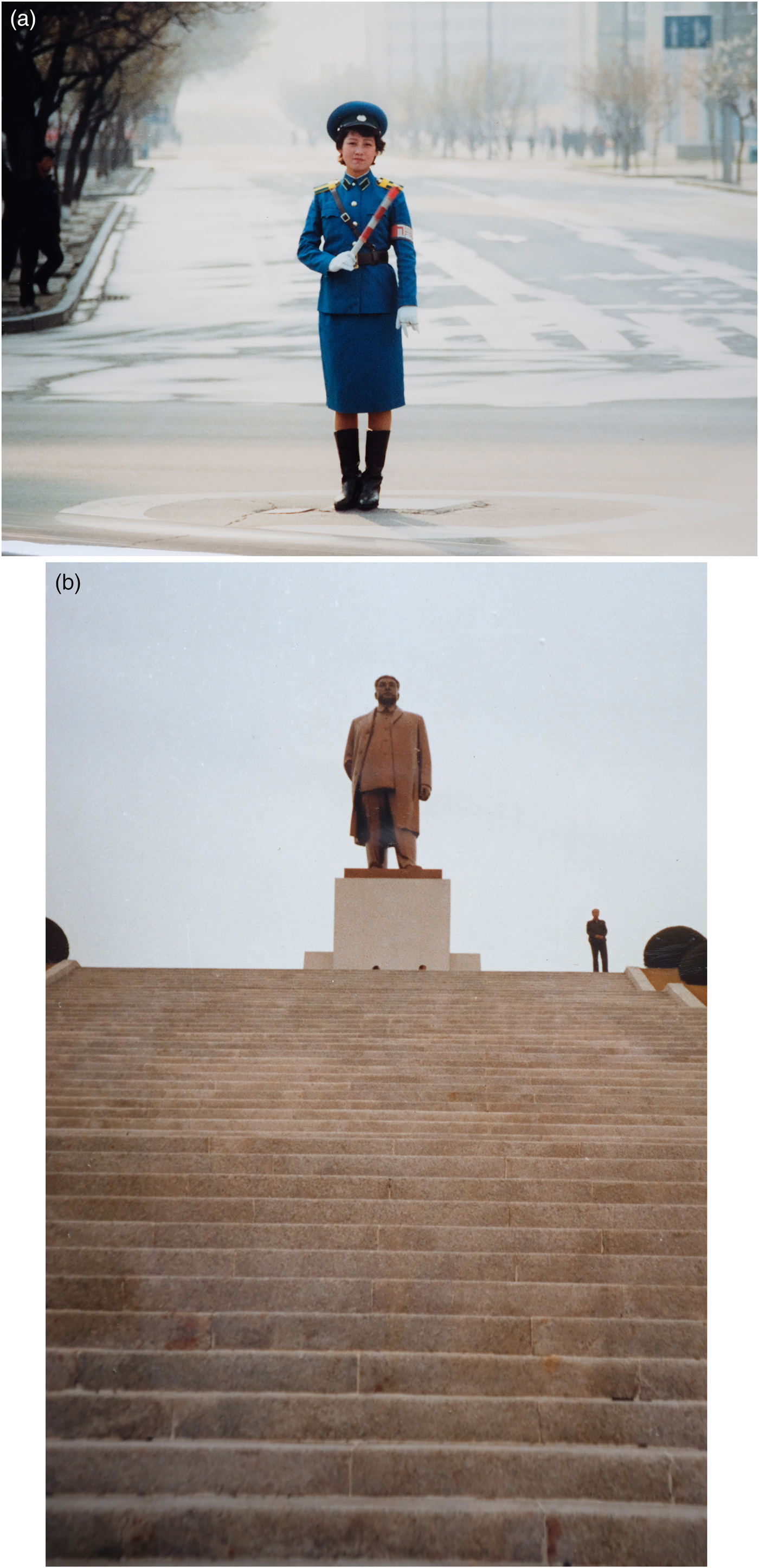

This dominant narrative is reflected in some of my photographs of North Korea, particularly those of Pyongyang. Appearing clean and modern, there are photographs of gargantuan statues and towers and wide multi-lane boulevards (Figure 8a). Uniformed traffic regulators were systematically positioned on the latter, except that there was no traffic to regulate, at least no more than the occasional lost-looking truck limping along. Then there was the personality cult around the country's first leader, Kim Il-sung, which permeated all aspects of life, visually and verbally (Figure 8b). Most rooms had a portrait of Kim and everything revolved around him. For us, this involved visits to the normal sites that make up North Korea's hagiographic narrative: Kim's birthplace Man'gyŏngdae (see Figure 3), museums that celebrated his anti-colonial struggle, or ‘mass games’ that featured tens of thousands of children delivering a stunning but frighteningly flawless performance about the country's foundation and its great leader.

Figures 8. (a) Police officer regulating traffic in Pyongyang (1986–8); (b) Man next to Kim Il-sung statue, Kaesong (1986–8) © Roland Bleiker.

North Korea's visual and political narrative can easily be critiqued. And my own experience and photographs do, indeed, offer plenty of visual evidence that undermines the notion of a progressive and thriving society. Driving from Kaesong to Pyongyang, for instance, one could witness not only beautiful scenery but also extreme hardship: entire roads being built by thousands of workers quite literally by hand. Assault tanks were the only machinery available to flatten the road. Big banners and loudspeakers would fire up the workers, who laboured away in often extreme, sub-zero temperatures. While I was not allowed to photograph the respective sites, I have plenty of visual evidence that documents hardship and inequality in Kaesong, Pyongyang, and elsewhere (Figure 9). This personal photographic evidence is, of course, amplified by what we know happens behind what is visible: the exceptionally ruthless treatment of anyone dissenting with the regime; the horrifying ‘gulags’ that are documented by accounts from defectors.Footnote 42

Figure 9. Woman collecting herbs in Pyongyang (1986–8) © Roland Bleiker.

North Korea is, of course, seen in a completely different light from the outside. When viewed from South Korea and from much of the Western world, we encounter the polar opposite: visualisations of the most closed and most authoritarian society on earth, of a dysfunctional and irrational regime that revolves around a personality cult and an anachronistic communist ideology of self-reliance: juche. Massive human rights violations are part of this view as are shocking economic mismanagement. North Korea here is the exception in a region that, over the past decades, has steadily reduced instances of mass atrocities and moved towards democracy and economic development.Footnote 43 What remains is a seemingly irrational and aggressive ‘rogue regime’ whose nuclear ambitions and brinkmanship tactics regularly create major security crises in the region.

My own experience of living in the DMZ and visiting North Korea on a regular basis confirms this prevailing perspective, at least up to a certain point. North Korea was, indeed, incredibly closed and authoritarian. We regularly travelled to and stayed in North Korea and it was astonishing to observe how the state managed to seal off the country from virtually all information sources other than state-sanctioned ones. The dominant Western view of North Korea advances a depiction of the country that is both accurate and incomplete.

While authoritarian and dangerous, North Korea is also more complex. Take one widely spread view of North Korea, perpetuated by prevailing visualisations in much of the Western media: that of a grim land of destitution where oppression is so omnipresent that there is no space for anything else. This prevailing vision is perfectly captured by one of the most influential photographic essays of North Korea entitled ‘The Land of No Smiles’. Published by Foreign Policy, it features the work by Tomas van Houtryve.Footnote 44 David Shim puts this photographic essay in the context of broader visualisations of North Korea and highlights a prominent theme: the depiction of a country ‘solely by distress, depression and desperation’, a place without ‘happy and cheerful people’.Footnote 45

My experiences in North Korea – and my viewing of the photographs from back then – paint a more nuanced picture. Yes, there was poverty and oppression and despair. But there were also a lot of people going about their everyday life, including doing so with seeming joy. There were certainly many smiles, not only in officially staged settings, but also in everyday life (Figures 10, 12, 13).

Figure 10. ‘The land of no smiles I’, Man'gyŏngdae, North Korea (1986–8) © Roland Bleiker.

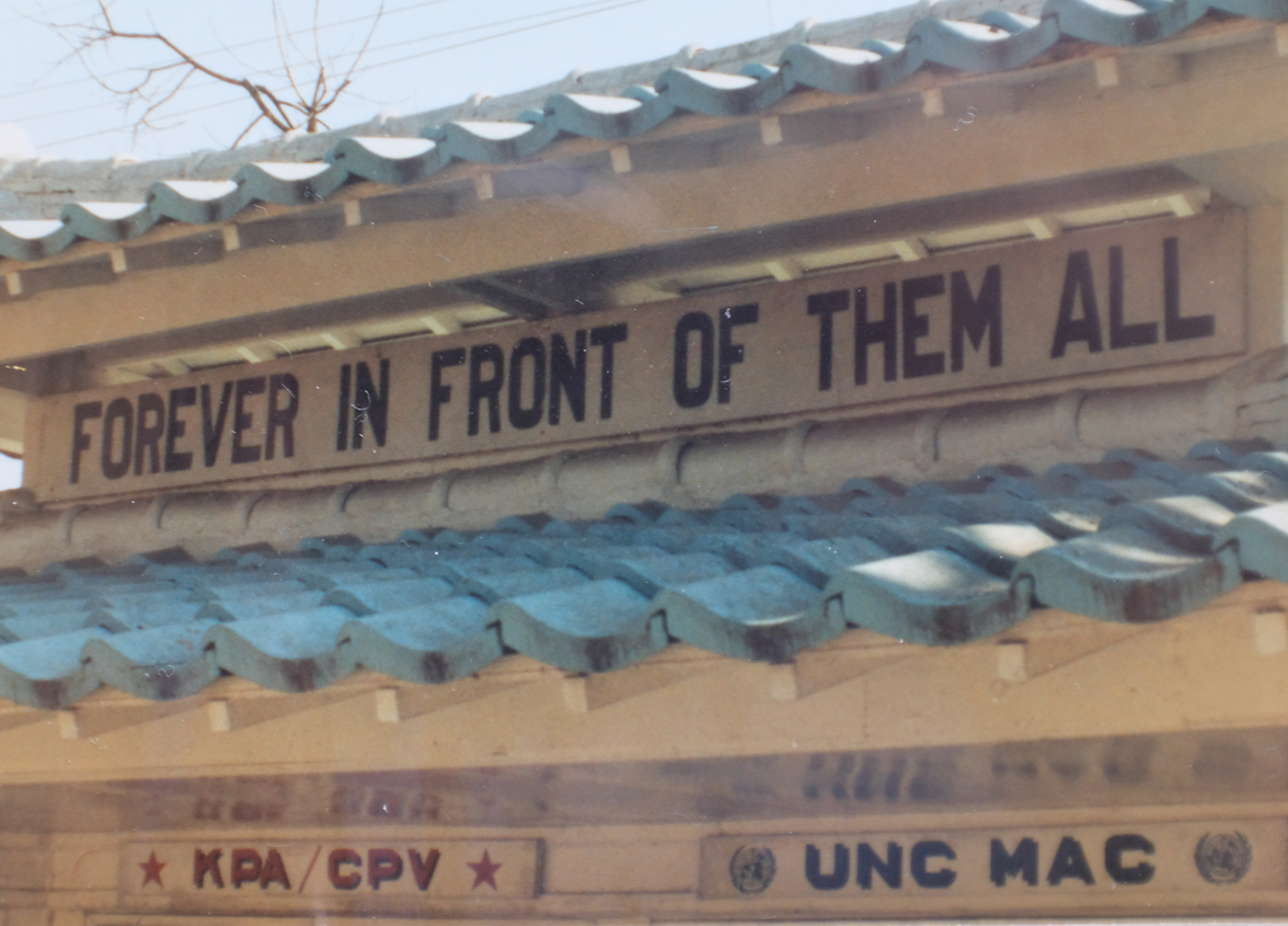

Figure 11. ‘Forever in front of them all’, Camp Bonifas, United Nations Command, DMZ (1986–8) © Roland Bleiker.

Figure 12. ‘The land of no-smiles II’ (1986–8) © Roland Bleiker.

Figure 13. Pyongyang (1986–8) © Roland Bleiker.

In sum: I offer a very short sketch here that tries to make one simple point: that my own photographs of North Korea, subjective as they are, reveal how both prevailing visual narratives of the North – the one promoted in Pyongyang and the one prevailing in the West – are partial and biased in nature. I do not claim that my photographs somehow offer a more authentic take on North Korea. They do not. They inevitably reflect my experience and my aesthetic choices as a photographer. But my photographs – and the positionality they embody – nevertheless reveal something that is of political significance: that both prevailing discourses about North Korea are selective and they are highly political in their selectivity. These discourses reflect the political positions they embody and, in doing so, say as much about the values of the viewers than they do about what is actually visualised: life in North Korea.

Forever in front of them all or, a rogue is a rogue is a rogue

Significant consequences follow from recognising that prevailing visualisations of North Korea are partial. Images frame the world and, in doing so, circumvent not only what is being seen but also how we – as collectives – perceive an issue and view it politically. Visuals construct common sense: they provide us with a view of the world that eventually becomes so accepted and self-evident that its arbitrary origins are no longer recognised.

This is why prevailing visualisations of North Korea shape both international press coverage and the positions espoused by key policymakers, most notably the South Korea and the US.

The image of North Korea as a rogue state is so entrenched that we cannot see anything else: ‘a rouge is a rogue is a rouge’, as I put it a while ago.Footnote 46 North Korea is, in short, the ultimate ‘other’ the communist and authoritarian state that defies the socio-political logic of the international liberal order; the one that stands still even after the collapse of the Soviet Union and even after remaining communist states, such as China and Vietnam, introduced major economic and political changes. Consider the main slogan rehearsed by American or South Korean troops in the DMZ: the notion that ‘we’ are ‘forever in front of them all’, defending freedom against the threat of evil communism north of the dividing line (Figure 11).

This political and visual depiction of North Korea stubbornly persists, even in the face of contrary evidence. And such evidence abounds. There are meanwhile numerous studies about North Korea that challenge the prevailing narratives. But they remain largely ignored by policymakers. These studies document everyday life and reveal it as far more complex than commonly assumed.Footnote 47 There are also studies that show how North Korea has acted largely in a rational and predictable manner. It might be an authoritarian relic of the past, but the mere fact that the country survived against all odds – a small and poor country surrounded by a hostile world – is testimony for how successful its leaders have been in manipulating larger players in international politics.Footnote 48 Despite this evidence the prevailing stereotypical cliché of North Korea largely persists: that of an irrational, unpredictable, and mad country. As late as 2018 mainstream press coverage still presented North Korea's leader, Kim Jong-un, as ‘an unpredictable, unknown quantity capable to lashing out at other countries without reason’.Footnote 49

How, then, can a small visual autoethnography help to stimulate a rethinking of this entrenched image and political dilemma? For one, it can make us aware of the need to question the prejudices we – as individuals and collectives – have about North Korea. We might never be able to see beyond the country as the ‘ultimate other’ but we can, at least, be more informed about the complexities that are entailed in the political dynamics involved, including our own bias. My entire experience in Korea – as well as lots of other evidence – suggest that it is impossible to advance a neutral and objective position. I have flagged in previous studies that there is no such thing as ‘objective reality’, especially not in the context of the deeply divided and hotly disputed Korean peninsula.Footnote 50 Security policy always revolves not only around factual occurrences, but also, and above all, around the projection and evaluation of threats. The latter are inevitably matters of perception and judgement. Strategic ‘reality’ in Korea is the reality seen through the lenses of the strategic studies paradigm. This paradigm filters or selects information in a way that sets limits to what can and cannot be recognised as ‘real’ and ‘realistic’. In view of these dynamics one must inevitably ask: what kind of ‘reality’ is being depicted by the prevailing view? Who is viewing and with what purpose and interests? Who has the power to determine what can and cannot be seen and, thus, what can and cannot be thought? What are the consequences?

Needed, in other words, are not approaches based on North Korea ‘as it is’ but on understanding how the current security dilemmas has emerged and how they can be understood in their complex causes and manifestations. Innovative solutions are required that go beyond the two approaches that policymakers keep coming back to but have not achieved stability or security: countering North Korea with military threats and economic sanctions.

I can only offer one very brief illustration here: the need to make an effort to imagine how life – as well as politics and security – looks like from North Korea. The first and undoubtedly most striking feature to notice from Pyongyang would be the long history of US nuclear presence in the region. Equally obvious and understandable is that this presence must have been – and continues to be – interpreted as a threat to North Korea's security. Issues here include the US use of nuclear weapons in close proximity to Korea – in Hiroshima and Nagasaki – and the deployment of ground-based nuclear weapons to South Korea after the war. As recently as 2017 US president Donald Trump designated North Korea's leader as ‘rocket man’ and stressed that ‘I too have a Nuclear Button, but it is a much bigger & more powerful one than his, and my Button works!’.Footnote 51 In view of such threats it is not surprising that North Korea has aimed to develop a nuclear deterrent. Most Western ‘decisions makers’ would, presumably, have embarked on similar policies if faced with such threats.

Understanding Pyongyang's policy decisions as rational is not to deny that nuclear proliferation is a great danger and a major security problem in the region. Nor is it to justify the country's human rights violations. But appreciating alternative vantage points can help to both understand and predict North Korean behaviour. It might also be a way to find new solution to entrenched political dilemmas. One can agree or disagree with North Korea's dramatic brinkmanship tactic, but one cannot ignore its deeply entrenched existence. Doing so may lead to dangerous miscalculations. At minimum, it prevents us from recognising how Pyongyang may be using its last bargaining chip, its nuclear potential, as a way of entering into dialogue with the US and other key states. But despite numerous and obvious signs, and despite detailed and insightful studies of North Korea's previous negotiation behaviour, most Western decision-makers repeated exactly the same mistakes they committed in the past: they believed that by demonising North Korea as an evil rogue state they could force Pyongyang into concessions. The result was not a solution to the conflict but a further escalation of threats and counter-threats.

Conclusion: What can visual autoethnography add to understanding security dilemmas?

The purpose of this article has been to explore how my experience of working in the DMZ, and my own photographs from that time, can shed new light on the conflict in Korea. This is neither an exercise in policy analysis nor an attempt to explore the latest political developments on the peninsula. A short analysis of this nature can, at best, draw attention to the potential of visual autoethnography to shed light on political phenomena.

The DMZ is far more than a physical border. It delineates what each side can see about the political and what not. In doing so, the DMZ also delineates what can and cannot be sensed, felt, and articulated about the political. The issues at stake here are, ultimately, of core importance to security policies for they influence who has the power to speak about what and whom and in which ways.

I have tried to show how my own experiences and photographs can offer two types of insights into security dilemmas on the Korean peninsula.

First I demonstrated how visual autoethnography can reveal how militarised masculinities are so deeply entrenched that they are taken for granted and, in doing so, shape security policies in fundamental ways. Looking at my photographs of the DMZ today I notice one thing above all: their strikingly gendered nature. There are virtually no women in them. Particularly revealing for me – and politically significant – is that three decades ago, when I took these photographs, I noticed everything except the absence of women: I came from and was embedded in a context that rendered gendered systems of inclusion – and the problematic militaristic polices they facilitate – natural and largely invisible.

Second: reflecting on my positionality and my photographs show how both prevailing discourses about North Korea are partial and highly political: the one emanating from Pyongyang that glorifies the regime as well as the one prevailing in the West, which vilifies the North and presents it as an authoritarian rogue regime whose irrational leadership regularly threatens regional and world peace. Visual positionality here offers pathways to appreciate the more complex nature of the Korean conflict and envisage innovative ways of understanding and addressing its security dilemmas.

Visual autoethnography is, of course, not the only way to question prevailing ways of understanding security dilemmas and to offer alternative ways of addressing them. Innovative solutions can and have been advanced in through different forms of inquiry. But visual autoethnography can make a valuable contribution to debates on security and international politics in general.

This, then, has been the main argument of the article: that the usefulness and the power of visual autoethnography lies in its ability to reveal how prevailing ways of seeing, thinking, and conducting security politics are so deeply entrenched and taken-for-granted that their often problematic nature is no longer recognised, yet alone discussed and addressed. My own photographs have shown this process in Korea not because my visualisations are somehow authentic, unique or systematic, but because they stand in contrast to prevailing images. In this sense, my photographs are not representative of something, but against something and, in doing so, expose how common visual and political discourses have been framed and naturalised to the point that they have the power construct common sense.

At least two broader consequences emerge from my inquiry. They have to do with the larger processes through which seeing, feeling, and understanding the world are inevitably political in nature.

First: visual autoethnography draws attention to the embodiedness of seeing and knowing the world and the political implications that issue from this recognition. When we – as individuals and as collectives – visualise and represent the world we say as much about us as seers and knowers than about the actual situation that is being depicted. Knowledge is inevitably embedded in experience, in how we are situated and how this situatedness shapes our understanding of the world.

Second: a certain level of epistemological modesty, caution, and self-reflection is required once we recognise that experience is mediated, that knowledge is situated and continent on how we see, feel, and represent the world. Every political position or scholarly analysis is inevitably partial. This is not only the case in Korea, where deeply entrenched and emotionally charged antagonisms render neutral positions impossible. Knowledge is never neutral. It is thus all the more important to advance political propositions in a self-reflective manner. Rather than hiding the choices made in the interpretation of political phenomena, scholars should expose them and lay bare the paths taken and forgone. Doing so entails a certain level of scholarly humbleness. Acknowledging the nature of visual and political discourses – and the link between them – is to accept that there is no outside: we are inevitably caught in a web of meanings and we can only be aware of part of them.

Accepting the limits of knowledge should not end up in despair, but quite the contrary, can generate innovative solutions to entrenched political problems. Genuinely new insights rarely emerge from approaches that seek ever more systematic and authentic knowledge. We should, rather, look towards innovative reflections on the contingent nature of all knowledge. We need to investigate how prevailing ways of seeing and understanding the world have created political dilemmas that are so deeply entrenched that they seem intractable. This is precisely where visual autoethnography can help: by exploring and theorising one's own positionality in a self-aware way one can develop the type of empathy necessary to imagine the world – including the political world – from a range of perspectives. How else can we understand and address the key political challenges of our time?

Acknowledgements

This article has gone through several almost complete rewrites. I would like to express my gratitude for the insightful feedback I received along the way, most notably from three anonymous referees, and from April Biccum, Muriel Bruttin, Anthony Burke, Bill Callahan, Federica Caso, Shine Choi, Iain Cowie, Toni Erskine, Sandra Fahy, Emma Hutchison, Lene Hansen, David Hundt, Ihntaek Hwan, Andy Jackson, Anna Leander, Matthew Longo, Iver Neumann, Ximena Osorio, Rune Saugman, Janjira Sombatpoonsiri, Jay Song, David Shim, Shreya Singh, and the editors of EJIS and the Special Issue, in particular Jonathan Austin, Timothy Edmunds, and Christian Brugger. Thanks also for support from my former NNSC colleagues and co-photographers, most notably Urs Fischer and Herbert Amrein, and comments from audiences at the LSE in London, the Graduate Institute Geneva, Thammasat University in Bangkok, Australian National University in Canberra, Monash University in Melbourne, Griffith Asia Institute in Brisbane as well as the 5th European International Studies Association Workshops in Groningen and the IPSA World Congress in Brisbane.

Roland Bleiker is Professor of International Relations at the University of Queensland, where he coordinates an interdisciplinary research programme on Visual Politics. His research explores the political role of aesthetics, visuality, and emotions, which he examines across a range of issues, from security, humanitarianism, and peacebuilding to protest movements and the conflict in Korea. In a previous life he worked in the Korean Demilitarized Zone as Chief of Office of the Swiss Delegation to the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission. Bleiker's books include Popular Dissent, Human Agency and Global Politics (Cambridge University Press, 2000); Divided Korea: Toward a Culture of Reconciliation (University of Minnesota Press, 2005/2008), Aesthetics and World Politics (Palgrave, 2009/2012); and, most recently and as an editor, Visual Global Politics (Routledge, 2018).