Introduction

Britain's fourth National Action Plan (NAP) on Women, Peace and Security (WPS) was published in 2018. For the first time in its history, it referenced women in relation to the international counterterrorism agenda using the language of preventing and countering violent extremism’, or ‘P/CVE’, which became an internationally recognised United Nations policy agenda in the years following 9/11. P/CVE policies and programming respond to the activities of terrorist or violent extremist actors; it refers to the ‘softer’ security-centred activities that occupy a sprawling and (largely) undefined space between international development work and military interventions. Although the integration of P/CVE and WPS was a direct response to the passing of United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 2242 and the UN's call to Member States to more closely integrate gender as a cross-cutting issue in the context of the WPS, counterterrorism, and countering violent extremism efforts,Footnote 3 this move also marks an institutional shift in terms of Britain's discursive and operational practising of development, security, and counterterrorism. This shift represents the crystallisation of the integrated development-security-counterterrorism agenda that had been advancing since 9/11, and which culminated in the dissolution of the Department for International Development (DFID) in 2019.

When it was created in 1997, DFID had hoped to be a beacon of its time, and to ‘give much greater priority to international development than our predecessors’.Footnote 4 However, following 9/11, the UK government proceeded to pursue an integrationist development-security-counterterrorism agenda whereby Britain's development objectives evolved from being entirely grounded in human development and human security to being integrated as a strategic pillar within the broader British national security agenda. The effects of this strategic move had both conceptual and organisational impacts. Conceptually, the move saw the prioritisation of conflict prevention work that was linked to national security priorities, such as counterterrorism and countering violent extremism (CVE). Organisationally, at the ministerial level, institutional discourses of DFID, the Foreign Office (FCO now FCDO), and the Ministry of Defence (MOD) merged and broadened the existing development-security agenda to include counterterrorism-related issues and concerns. The overlapping and contesting discourses between the joint FCO-DFID-MOD agenda for international security, development, and countering terrorism produced new discourses and practices through a ‘development-security-counterterrorism nexus’,Footnote 5 which simultaneously broadened the scope of the development agenda to include counterterrorism aims and objectives, but diluted the focus of international development and its original priorities.Footnote 6 The merging and broadening of the development-security agendas to include counterterrorism issues of women's rights, equality, and (in)security in ‘fragile’ or ‘conflict affected’ nations with fighting terrorism and violent extremism was problematic for three key reasons. Firstly gender-related activities that assumed women's rights and empowerment as outcomes of development-security-counterterrorism policy and programming, rarely actually had gender-sensitive and gender equality principles at the heart of their design. Instead, women's rights and empowerment were instrumentalised for broader security objectives, which not only inherently limited the effectiveness and reach of these projects, but often caused more harm than good to the individuals who were targeted. Second, gender sensitivity efforts were mainstreamed into countering violent extremism and counterterrorism efforts without being grounded in evidence with adverse consequences. Thirdly the security-oriented cultures and interests of the FCO and MOD sat uncomfortably next to DFID's development policies, which created considerable institutional incoherence, affecting how operations and programming were carried out through an integrated FCO-MOD-DFID agenda on the ground.

This research examines the competing and evolving representations of women and gender that are produced and reproduced through the discourses and practices of security, development, and counterterrorism within the ecosystem of actors and institutions of the development-security-counterterrorism nexus. The central research question guiding this research asks: how did gender-sensitive development work evolve after 9/11 and what factors influenced and shaped this evolution? In order to answer this question I have created an analytical framework through which I can examine gendered concepts of ‘security’ ‘counterterrorism’ and ‘development’, how they are practised and how they become institutionalised. Institutional analysis of counterterrorism rules, norms, and practices, and especially their gendered characteristics, has been minimal to date, therefore highlighting an interesting research gap, which this research hopes to address.

This article will be structured in the following way: First I will outline my methodology for conducting empirical institutional research. I will explain how I have developed my analytical framework, which constructs DFID as a site for the institutionalising of gendered discourses and practices. I situate DFID within the development-security-counterterrorism nexus which I suggest is where and how gendered discourses and practices are ‘(re)presented, (re)produced and (re)legitimised’.Footnote 7 There is a co-constitutive relationship between actors, organisations, and discourses within the nexus that does not necessarily see clear boundaries between formal rules, informal norms, and institutional practices.Footnote 8 I locate my framework within the broader theoretical context of feminist discursive institutionalism, specifically owing a theoretical debt to a Foucauldian interpretation of discourse as practice. I conclude this section by referencing the limitations to this research as well as potential contributions it could make to the literature.

The second section comprises my empirical analysis. I first trace the production of the development-security-counterterrorism nexus and its evolution in a post-9/11 context. I focus on how representations of women and gender in relation to development, security, and counterterrorism have evolved through examining the discursive practices of DFID between 1997 and 2019. Next I trace the practices of the nexus through DFID's development, security, and counterterrorism gender programming agendas. Third, I explore how and when the gender and counterterrorism agendas were integrated, and finally I consider how interactions with civil society could provide contesting discourses that may contribute to institutional evolution and which could impact gender agenda in the context of the nexus. I conclude with some key findings that suggest that gendered understandings of security, development, and counterterrorism are reflective the result of institutional hangovers – or legacies of the past – that remain sedimented across the nexus, and are reproduced through the discourses and practices of DFID and the wider nexus actors. Even though some gendered institutional evolution can be observed, these shifts have either been cursory meaning that they have not penetrated the social logics propping up the institution or when they have gone deeper, the change happens extremely slowly.

Designing the analytical framework

This research interrogates how knowledge production and meanings about women, gender, (counter)terrorism, and development have evolved in an institutional context. I am therefore interested in emphasising how discourses are articulated. Using feminist institutionalism and discourse analysis, I trace how concepts of women and gender are articulated through textual material produced by DFID during its tenure (1997–2019) to investigate how and where gender operates within an ecosystem of security actors that occupy different layers within the development-security-counterterrorism nexus.

There are many ways to carry out feminist institutionalist research.Footnote 9 I draw from the tradition of feminist discursive institutionalism because I place a distinct emphasis on language, and the way that it is bound up in systems of meaning and knowledge production. This approach allows me to do the following: (1) to conduct an inter-institutional analysis of DFID and key partners to analyse how gendered development programming evolved over the course of its tenure, and how counterterrorism became embedded within the development agenda; (2) to examine the co-constitutive relationship between informal and formal institutional dynamics (rules, norms, and practices) that will explain how certain discourses remain more resilient than others; (3) to locate gender and reveal the myriad of ways that women (and men) are integrated into development-security-counterterrorism discourses and practices; and finally (4) to be able to capture the practices of DFID and associated institutions in the context of the development-security-counterterrorism nexus.

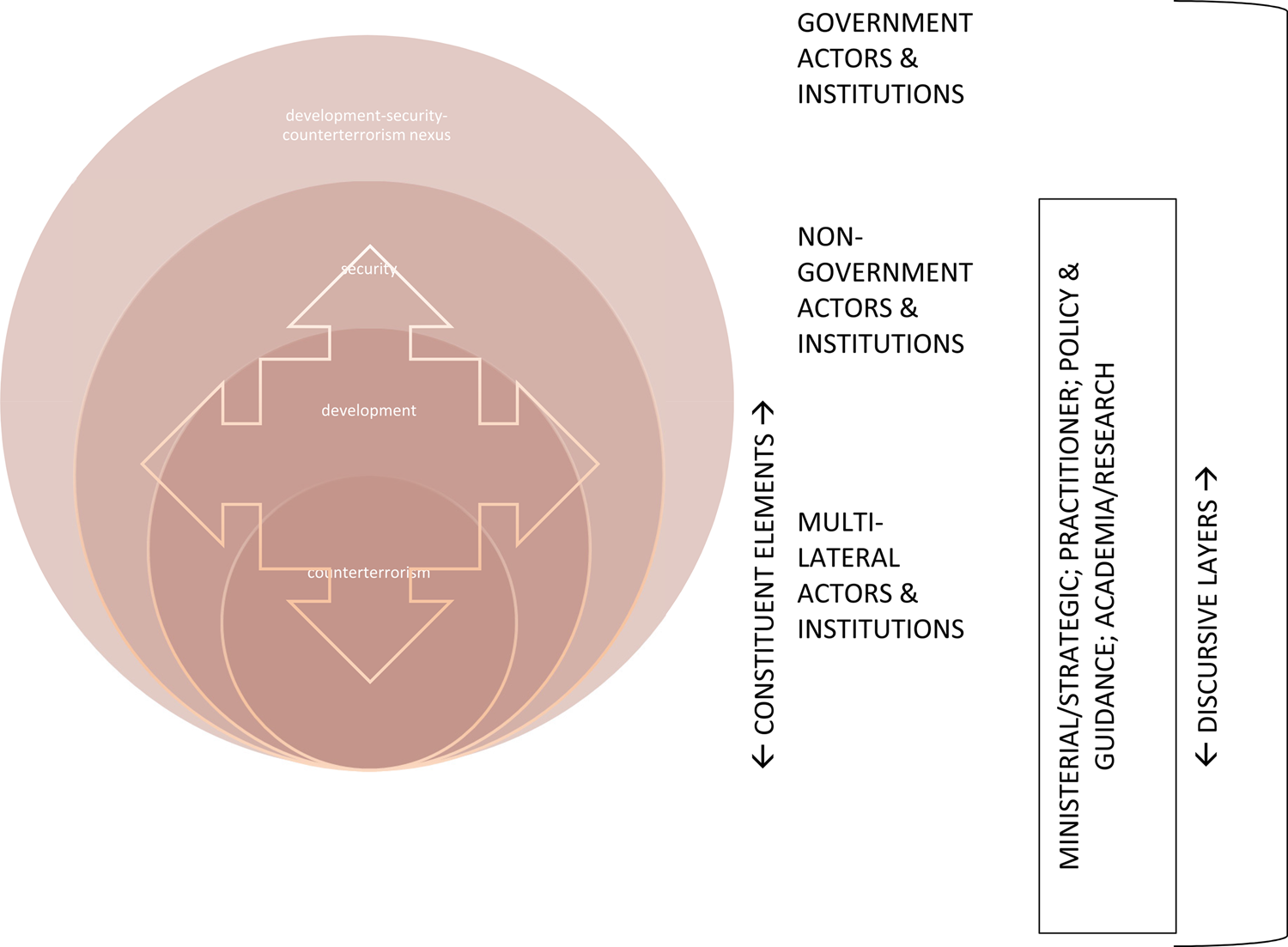

The framework that I have developed allows for inter-institutional gendered discourses and practices to be examined thereby capturing the dynamic ways that institutions produce and reproduce representations about women, as well as how their competing and overlapping discourses interact in the context of the development-security-counterterrorism nexus. Furthermore, the framework is replicable and can be applied to carry out examinations of the discourses and practices produced through and by other institutions operating within the nexus such as the MOD or the FCO, or indeed at the multilateral level such as UN entities participating within the development-security-counterterrorism nexus. I chose to focus on DFID for this research for two key reasons. Being the Ministerial department in charge of designing and implementing Britain's international development policy and programming during this time, DFID represents a core site for both the institutionalisation of gendered discourses and practices and for examining how the reproduction of these discourses and practices have shaped gender-sensitive development policy and programming within the development-security-counterterrorism nexus and its ecosystem of security actors. Additionally, DFID offers a rare opportunity to examine the evolution of a government institution from inception to discontinuation, thereby being an interesting case study through which to form insights about institutional evolution both in terms of its status as a stand alone department and in terms of the way its discourses and practices interacted with those of other institutions within the development-security-counterterrorism nexus. Figure 1 captures the ecosystem of the ‘development-security-counterterrorism’ nexus.

Figure 1. The ecosystem of security actors within the development-security-counterterrorism nexus.

The diagram depicts how discourses and practices are produced and reproduced through an ecosystem of actors and organisations. Within the development-security-counterterrorism nexus there are three institutional policy spheres (‘development’, ‘counterterrorism’, and ‘security’) across which three constituent elements (government actors; non-government actors; multilateral partners) are operating and where four discursive layers (ministerial/strategic; practitioner; policy and guidance; academia/research) are being articulated and practised. Constituent elements are present across all institutional spheres and there are no firm boundaries between them; they are blurred, overlapping, and permeable. DFID is one of the constituent elements, sitting alongside other government departments (for example, FCO, MOD, Cabinet Office), non-government actors (for example, NGOs, civil society organisations, think tanks) and multilaterals (for example, UN, EU, World Bank). All of these constituent elements produce and reproduce discourses about gender and women in the context of development, security, and counterterrorism, and it is through their articulations of these discourses and their associated practices that the nexus is produced.

Through a process of intertextual linking and discourse analysis, I use this framework to examine how gender logics have evolved both within DFID and across partner institutions (constituent elements). I examined over 130 documents produced by DFID, alongside relevant interdepartmental policy documents, civil society documents, programme evaluation reports, and consultation papers as well as academic research. This material is supported by Ministerial speeches and statements and half a dozen elite interviews with former and current development-security-counterterrorism civil servants and practitioners. Taking a Foucauldian approach, the interview data provides insight into how actors (or subjects) are constituted through discourse which captures the ‘actual working of discourse as a constitutive part of social practices situated in specific contexts’,Footnote 10 or in other words, is a helpful way to capture how knowledge about women and gender is both reproduced through discourse and practice and how the actors involved in the nexus are themselves a product of the discourse. I can capture the formal and informal in this way and I can also identify how institutional evolution takes place.

Situating the framework within the literature: Feminist institutionalism, institutional evolution, and representations of women

How do representations of women vary within DFID's articulations of gendered discourse, and how and in what ways does the development-security-counterterrorism nexus reproduce, reinforce, or contest these representations? Feminist institutional analysis provides the tools to answer these questions by revealing the gendered characteristics of institutions and their processes of evolution or stagnation. As argued by Ann-Kathrin Rothermel, ‘feminist institutional analysis provides a useful perspective to expose complex, informal and often contradictory and unintended processes of “institutional stability, change and erosion and reconstruction” which are otherwise easily overlooked.’Footnote 11 Feminist institutionalists emphasise the crucial relationships between institutional norms, rules, and practices – formal and informal – and examine how their interaction sustains the presence of a ‘gender regime’ that operates in all institutional contexts. This process explains how (mostly invisible) gender logics and inequalities are sustained and persist across institutional sites.

Feminist institutionalism is a heterogeneous field with a number of different epistemological pathways of which feminist discursive institutionalism is one. I draw from Carol Bacchi and Malin Rönnblom'sFootnote 12 poststructuralist approach to feminist discursive institutionalism rooted in a Foucauldian understanding of power relations. This approach differs from mainstream feminist discursive institutionalist approachesFootnote 13 most profoundly due to their limited and constrained explanationsFootnote 14 of institutional evolution and the relationship between power, ideas, agency, and discourse(s). A Foucauldian understanding of power, agency, and discourse(s) applies a more fluid and dynamic understanding of power, suggesting that ‘power produces conditions of meaning, instances of meaning, webs of meaning that are both locally specific and “run through the whole social body”’.Footnote 15 Discourse is therefore essential to the construction of knowledge about women, development, security, and (counter)terrorism, and ‘Discourse analytical strategies provide means to assess how particular meanings of gender are set in relation to institutional goals, norms and principles through articulations or practices of institutional actors.’Footnote 16 It is through an examination of the competing and overlapping representations of women that are discursively produced by DFID and reproduced through the nexus that we can locate gender in an institutional context. As argued by Laura Shepherd, ‘Discourses are therefore recognizable [to me] as systems of meaning-production rather than simply statements or language, systems that “fix” meaning, however temporarily, and enable us to make sense of the world.’Footnote 17 Taking a Foucauldian approach to discursive institutional analysis therefore differs from Vivien Schmidt's approachFootnote 18 most profoundly in its explanation of institutional evolution and the relationship between power, ideas, agency, and discourse(s).

If we accept that discourses can fix meaning, then discourses can also produce (and be productive of) change. The ability for sedimented or institutionalised discourses to be ‘destabilised’ is dependent on how ‘sticky’ or resilient they are. ‘Stickiness’ is not a very technical term but it helpfully describes the ways that discourses and practices interact to facilitate or undermine institutional evolution. Thomas JacobsFootnote 19 suggests that institutional evolution is made possible through the process of destabilising homogenising ‘social logics’ – or institutionalised discourses – and introducing ‘political logics’ – or competing discourses. ‘Social logics’ can be understood as institutional characteristicsFootnote 20 or ‘integral patterns of social life’.Footnote 21 ‘Political logics’ can be described as discourses that ‘govern how we try to contest what is normal and how we try to instate new or defend old conventions and “normals”’.Footnote 22 In order for institutional practices to evolve, the social logics, or workplace habits are contested through the presence of counter-discourses or political logics. Political logics are therefore important sites for contesting the dominant discourses; Jacobs writes, ‘political logics thus make the transformation of social patterns possible by revealing the arbitrary nature of the discursive structure in which they are embedded.’Footnote 23 Discursive evolution is a process through which certain discourses become more or less engrained or ‘sedimented’Footnote 24 depending on the presence of alternative ideas and knowledges. Examining this process helps us understand and explain how and why institutions evolve. In other words, the introduction of political logics – or contesting discourses – may lead to an evolution in representations of women and gender. However, the saliency of such discursive evolution is dependent upon the transfer of power through discursive reproduction. For example, Louise Chappell and Georgia Waylen argue that the ‘gender regime’ does not get disrupted because men's bodies become replaced by women's; rather this gender bias is governed by social norms and conventions (social logics) that have become institutionalised in particular settings over time. These gendered logics ‘prescribes (as well as proscribes) “acceptable” masculine and feminine forms of behaviour, rules, and values for men and women within institutions.’Footnote 25 The presence of persistent or competing gendered logics therefore helps to explain how certain representations of women and gender become institutionalised and destabilised at any given time, within different institutional policy spheres or constituent elements.

While there is no correct way to apply institutional analysis to the political field,Footnote 26 the approach that I offer allows me to ‘move beyond the description stage and systematically identify particular gendered institutional processes and mechanisms and their gendered effects’.Footnote 27 This framework captures the dynamic relationship between formal and informal institutional interactions, suggesting that institutional change is the result of discourses shifting their ‘logic positions’. Gendered rules, norms, and practices are therefore products of discursive articulations that become imbued with meaning within specific institutional contexts; this meaning is variable and can shift across institutions and actors within the development-security-counterterrorism nexus.

Although institutionalist theorising of political institutions is a well-trodden field, within (counter)terrorism and security scholarship it remains relatively unusual. Frank FoleyFootnote 28 utilised a sociological and historical ‘new institutionalist’ approach to examine the evolution of counterterrorism in Britain and France, which emphasises causal pathways in understanding institutional evolution. While the research is valuable in terms of explaining why different institutional changes occurred (or did not) within the counterterrorism infrastructure in Britain and France, the focus on external factors, and the lack of attention to the gendered foundations of counterterrorism institutions leaves a clear research gap to be filled. Ann-Katherin Rothermel recently used feminist institutionalism to examine gender in the UN's counterterrorism reform.Footnote 29 Rothermel's framework brings together elements of historical and discursive institutionalisms – such as ‘nested newness’ and ‘institutional layering’Footnote 30 – to ‘uncover different (or even contradictory) coexisting gender representations and the corresponding institutional gendered logics structuring the inter-institutional counterterrorism reform process’Footnote 31 at the UN level. This approach is reflective of Teresa Kulawik's ‘integrated approach’,Footnote 32 which I depart from slightly. The focus of my analysis is not necessarily on ‘inter-institutional reforms’.Footnote 33 Rather, I seek to examine the evolution of discursive representations of women in relation to DFID's development, security, and counterterrorism policies and programming.

This research is situated at an intersection between feminist institutionalism, feminist security studies, and terrorism studies. My framework offers an original approach to feminist discursive institutionalism, which connects debates about gender, development, and (counter)terrorism across all three fields. By asking the question of how Britain's counterterrorism agenda influenced DFID's post-9/11 international development work and what role gender had in this process, I contribute to discussions about the relationship between gender, development, (in)security, and counterterrorism. While feminist theorising of political violence is not new,Footnote 34 feminist theorising of counterterrorism has grown since 2015, with UNSCR 2242 referencing women in the context of terrorism and violent extremism for the first time. I seek to add to this body of feminist scholarshipFootnote 35 specifically through my focus on counterterrorism.

A note here on the limitations of this study. One clear limitation is that I apply a very limited approach to my use of ‘gender’ in this article, which I inextricably link to the articulations and practices about women in the context of development, security, and counterterrorism. I realise that the scope of the framework is dynamic enough to readily be applied to interrogate different conceptualisations of gender such as with reference to men or masculinities or with reference to queer theory and non-binary identification. I chose to omit these important discussions of broader gender-related dynamics for the following reason. As feminist scholars (for example, those cited below) continue to emphasise, there remains an evidence gap with regard to the female experience(s) of terrorism, violent extremism, (in)security, and political violence. The picture we have is incomplete and has been shaped by decades of research and policymaking that have foregrounded a homogeneous male experience of international security and political violence and developed policy responses accordingly. Making the female experiences of international conflict, political violence, and (in)security visible remains important to create an evidence base from which policymakers can draw for future programming infrastructure. Future research could explore the question of ‘masculinities’ in the context of (in)security, political violence, and terrorism in a standalone research paper that focuses on exploring complex questions related to development objectives, links with violent extremism and (in)security. This research would then be able to explore the extent to which ‘male political dominance is reinforced and maintained in political institutions’Footnote 36 of the development-security-counterterrorism nexus, and could examine how constructions of masculinity have gendered implications beyond those on men, and include women's experiences as well.

I would also like to clarify the terms and language that I am using in this article. The terms ‘terrorism’, ‘counterterrorism’, ‘countering violent extremism’, and all related processes (for example, radicalisation, deradicalisation, disengagement, etc.) are inherently contested concepts with multiple meanings and interpretations. Indeed, among practitioners and policymakers, terms are often used interchangeably with no clear definition about what exactly is being referred to or clarity about the specific parameters of interventions. Due to the inconsistencies around what actually constitutes ‘counterterrorism activities’, and due to the constraints imposed by the scope of the article, I use a very broad definition of counterterrorism that encompasses all countering and preventing violent extremism activities. In this context, counterterrorism practices are best understood across a spectrum: at one end is the softer, preventing/countering violent extremism and conflict prevention-type work and at the other end is the hard, military, intelligence and law enforcement infrastructure.

Producing the development-security-counterterrorism nexus: Representations of women and gender pre- and post-9/11

In 1997, DFID was created from the ashes of the Overseas Development Administration (ODA) a division within the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO). The late 1990s saw the beginnings of the globalisation, mass migration, and international connectivity era, which prompted Western liberal democratic foreign aid policy and programming to ensure local and regional conflicts overseas did not affect national security back home. As such, a ‘development-security nexus’ emerged during the late 1990s, which legitimised a new security terrain. The development-security nexus was ‘mainly concerned with practical issues relating to the transition from humanitarian relief to sustainable development’,Footnote 37 however ultimately, ‘would-be recipients [of aid and assistance] have come to see international assistance as an extension of Western foreign policy.’Footnote 38

Prior to 9/11, the key aim of DFID's overseas development programming was focused on poverty reduction work, of which gender-sensitive programming formed a key part. The 1997 White Paper states that 70 per cent of the world's poorest people are women who are ‘the most vulnerable to all forms of violence and abuse, including domestic violence, crime and civil conflict’.Footnote 39 DFID's approach to and understanding of ‘security’ was in the context of security sector reform (SSR) and the 1999 Strategy paper, ‘Poverty and the Security Sector’ DFID cautiously outlined its new commitments to SSR. The paper is very specific about the parameters of security and ‘places definite limits on the relationship between development and security’Footnote 40 outlining a number of threshold conditions and criteria for the ‘boundaries of legitimate development involvement in the security sector’.Footnote 41 This approach to security established intertwined humanitarian aid and development work in ‘underdeveloped’, ‘fragile’, or ‘conflict-affected’ nations with security-related concerns. Through the discourse of ‘human security’ DFID and its international development agenda quickly became an important pillar in Britain's national security arsenal.

In a post-9/11 political environment, British development programming shifted from an entirely humanitarian-led agenda, to becoming part of the national security agenda, through a process of securitisation.Footnote 42 Jude Howell and Jeremy Lind define the ‘securitisation’ of development and aid as ‘the encapsulating of global and national security interests into the framing, structuring and implementation of development and aid’.Footnote 43 The ethos was such that ‘a more secure world is only possible if poor countries are given a real chance to develop.’Footnote 44 Through a process of discursively linking overseas threats such as terrorism, political violence, and war (the other) with British national security, safety, and stability (the self), the connection between development, security, and counterterrorism was established.

Shortly before 9/11 shifted the parameters of international relations forever, the landmark UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325 was implemented (in the year 2000), which finally put ‘women's security issues’ firmly on the international agenda. UNSCR 1325 was the beginning of what became known as the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda, which ‘addressed the impact of armed conflict on women and girls and the ways in which the full participation of women and girls in peace processes can significantly contribute to the maintenance and promotion of international peace and security’.Footnote 45 The Resolution's origins ‘lay in civil society, in the human rights, anti-war and women's movements’Footnote 46 and ‘provided an international framework for applying a gender perspective to international peace operations and security policy that acknowledges women's and men's different needs and experiences of conflict’.Footnote 47 The cross-cutting issues of women's rights, equality, and empowerment and (in)security, articulated through the WPS agenda were harnessed as a means to connect the parallel development, security, and counterterrorism agendas, and also to legitimise their eventual integration. This integrationist agenda to ‘doing’ development, security, and counterterrorism was institutionalised through the increased coordination and integration between DFID, the FCO, and the MOD to better coordinate work across three ‘Ds – development, diplomacy, and defence’,Footnote 48 which was reproduced through a new development-security-counterterrorism nexus. Neclâ Tschirgi argues that after 9/11, the nexus enabled state policies and practices to ‘move indiscriminately from the local to the global, from conflict prevention to peacebuilding, from humanitarian action to terrorism – creating tremendous conceptual as well as policy confusion’.Footnote 49 A strategic ‘whole of government approach’, which attempted to amalgamate poverty reduction, conflict prevention, and counterterrorism undoubtedly blended the development, foreign policy, security, and defence agendas. This strategy was operationalised through the creation of various interdepartmental initiatives (for example, Global and Conflict Prevention Pool and Sub-Saharan Africa conflict prevention pool)Footnote 50 and was reflected in funding terms. DFID's Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) commitments and priority areas for conflict prevention work and aid policy shifted towards nations that had been designated as fragile and vulnerable to violent extremism and terrorism after 9/11. Until 2002, Afghanistan had never received any ODA and until 2003 Iraq had not received any bilateral aid from the UK.Footnote 51 By 2008, Iraq became the top recipient of UK ODA, amounting to £639 million.Footnote 52 The 2010 Strategic Defence and Security (SDSR) review committed 30 per cent of DFID's ODAFootnote 53 to support conflict-affected and fragile states to tackle drivers of instability, which the 2011 counterterrorism strategy, CONTEST (to be discussed in detail below) declared as being ‘consistent’ with its own objectives.Footnote 54 By the time the 2015 SDSR was published, the government pledged 50 per cent of DFID's budget in fragile states and regions,Footnote 55 doubling down on the links between poverty reduction and tackling the root causes of terrorism. This move emphasised ‘a significant shift of UK development policy from a primary focus on poverty to a new dual focus on poverty and fragility’.Footnote 56 The government also announced plans to combine ODA with Non-ODA funding ‘into a resource that supports the implementation of National Security Council (NSC) strategies)’Footnote 57 through investing £1 billion into the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) to ‘prevent threats and build stability, as well as respond to crises more quickly and effectively’.Footnote 58 Counterterrorism work is included in their remit.

The integration of three very different departments, each with their own policy agendas, in pursuit of overlapping goals created a lack of coherence which undermined DFID's priorities and practices. A good example of this was made in a 2009 country evaluation report of Afghanistan. The authors state:

HMG's primary and more immediate focus on counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism – particularly with the UK's engagement in Helmand since 2006 – presents particular challenges for DFID. HMG has pursued simultaneous multiple objectives – counter insurgency, counter-narcotics, stabilisation, peace and development – under an assumption that each is mutually reinforcing. This is not necessarily the case.Footnote 59

Tracing institutional evolution

The consolidation of the integrated development-security-counterterrorism nexus through discourses and practices of securitisation can be traced through DFID policy and strategy documents. For example, in 1997, the White Paper only made 14 references to the word ‘security’, but by 2006, it was mentioned 81 times. In 1997 and 2000, the word ‘conflict’ was mentioned 29 and 47 times respectively in relation to issues such as conflict prevention, environmental degradation and social cohesion.Footnote 60 By 2006, conflict was mentioned 97 times, with more emphasis placed on ‘violent conflict prevention’ and ‘armed conflict prevention’. These challenges were linked strongly with weak governance, security and justice grievances, human rights abuses, insecurity, and conflict. The word ‘fragile’ was mentioned 21 times in 2006 and 50 times in the 2009 White Paper with a further 16 references to ‘fragility’. In these later White Papers, ‘fragile’ and ‘fragility’ are strongly related to state insecurity and underlying drivers of conflict.Footnote 61 The integration between the UK government's development and security agendas could not be more clearly emphasised than in the foreword to the 2005 Strategy paper, which states:

The poor therefore need security as much as they need clean water, schooling, or affordable health. In recent years, DFID has begun to bring security into the heart of its thinking and practice.Footnote 62

By 2006 – the year the first counter terrorism strategy was published – the connection between DFID's conflict prevention work and national security interests were well sedimented in development discourses. The 2006 White Paper states:

violent conflict and insecurity can spill over into neighbouring countries and provide cover for terrorists or organised crime groups.Footnote 63

The 2009 CONTEST strategy highlighted that the integrated approach to development-security-counterterrorism at both policy and programming levels was becoming more emphasised. The Cabinet Committee on National Security, International Relations and Development (NSID) had been established to oversee the delivery of CONTEST at home and overseas,Footnote 64 which reinforced the close cooperation between the FCO and DFID on overseas counterterrorism work. Furthermore, the overlapping FCO-DFID programming described within the document affirms this position. DFID is tasked with ‘addressing the underlying social and economic grievances that can make communities vulnerable to extremist messages’Footnote 65 as a contribution to CONTEST's overall counterterrorism priorities. This objective is considerably similar to that of the £87 million Prevent programme that is overseen by the FCO, which aims to ‘build the resilience of governments and communities … to tackle radicalisation and supporting communities to tackle extremism’.Footnote 66 DFID's local engagement work in Pakistan focusing on addressing underlying drivers of extremism and terrorism, is linked with British Muslim Pakistani communities living in the UK.Footnote 67 This example clearly demonstrates how the discourses connecting insecurity and instability overseas with violent extremism and terrorism were being practised. Not only was the development-security-counterterrorism nexus co-opting DFID's work for its strategic security objectives, but it reproduced a racialised and marginalising discourse that directly implicated British Muslims in constructions of the terrorist threat. Nicola Pratt's argument that ‘at the heart of the war on terror is the re-sexing of race and, through this, the production of the “dangerous brown men” as a threat to international security’Footnote 68 is therefore reproduced through the articulation of this policy discourse, which targets and implicates Muslim men and women in different ways through the practices of the development-security-counterterrorism nexus.

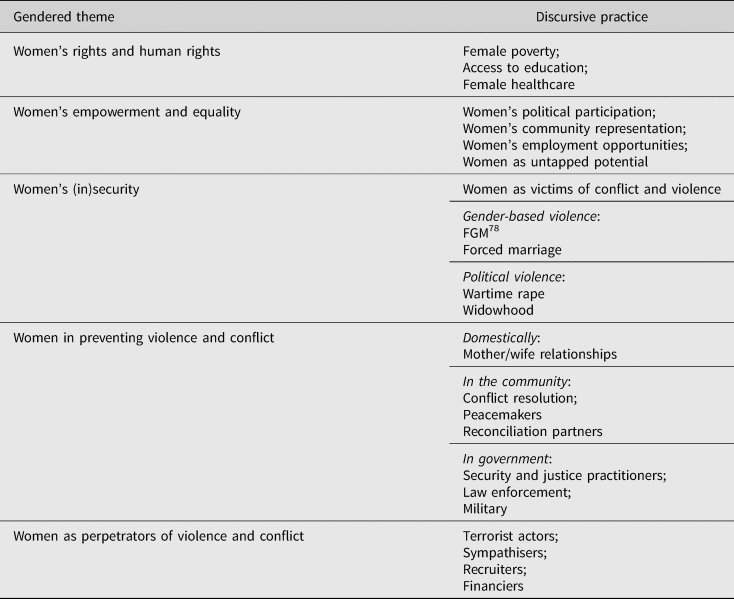

The evolution and securitisation of DFID's gender agenda can also be traced through its textual material. DFID strategy documents overwhelmingly describe women through five key gendered themes: women's rights and human rights; women's empowerment and equality; women's (in)security; women in preventing violence and conflict; and women as perpetrators of violence and conflict. Seven core DFID policy and strategic documents (not including National Action Plans [NAPs] or country-level reports) explicitly name women's rights, equality, and empowerment, and (in)security challenges as their focus.Footnote 69 In 2006, the link between gender and sexual/gender-based violence is first drawn. Until 2009, women are referenced in White Papers in relation to their vulnerability, depicting women as victims of sexual and gender-based violence (S/GBV), domestic abuse, child and forced marriage, and female genital mutilation, as well as emphasising the gendered challenges related to maternal healthcare, education, food production, economic opportunities, employment, and access to resources. These representations appear to be relatively homogenous, and heavily sedimented across all DFID literature until 2017. Although the links between women's equality and international security had been indirectly referenced and alluded to since around 2000/2001, the 2009 White Paper makes the first direct link between overseas insecurity, women's insecurity and British national security:

There is a real risk that the progress the world has made in tackling global poverty … could be reversed, with all that means for the welfare of the poorest and most vulnerable people in the world, particularly women, and also for the well-being and security of people living in the UK.Footnote 70

The reproduction of the securitisation discourse therefore changed how DFID's human rights-centred gender agenda was articulated and practised. The practice of discursively linking gender equality and women's rights with national security objectives was consistently articulated and remains key to the overall nexus project with the Secretary of State for International Development writing in 2018: ‘without progress on gender equality, achieving a safer world and a safer UK is simply not possible.’Footnote 71 The strategic discursive linkages made between under-development, insecurity, and gender inequality provided the UK government and international allies with a powerful and compelling narrative to justify Western interventionist policy overseas. Indeed, the interventions of Cherie Blair and Laura Bush in their addresses to their respective nations on the issue of women's rights in Afghanistan ‘provided the moral, feminine legitimacy to the bombing campaign’,Footnote 72 which commenced in late 2001. Through the articulation of discourses that frame foreign – mostly Muslim – women as being vulnerable on the one hand, and as the ‘missing link’ in counterterrorismFootnote 73 on the other, DFID and associated security institutions within the nexus successfully construct a ‘self’ and ‘other’ paradigm. Through this paradigm, the development-security-counterterrorism nexus reproduces discourse about women, gender, (in)security, connecting the advancement, empowerment, equality, and (in)security of foreign women, to British national security. For example, the 1997 White Paper depicted ‘poor women’ as fragile, vulnerable, incomplete, and unfulfilled; they are constructed as embodying the extreme poverty within which they live and are contrasted with the women living in ‘developed’ countries such as the US or the UK.Footnote 74 The referent object(s) – poor women – are constructed as an external ‘other’ whose plights are not shared by us in our prosperous nations. In this way, the war on terror discourse relies upon the ‘protection myth’ where ‘uncivilised bad men tortur[e] or threaten[ing] vulnerable and powerless women who require rescuing by enlightened and heroic “good” men.’Footnote 75 Furthermore, the juxtaposition between foreign, fragile, vulnerable women needing to be rescued by strong, Western masculinised interventions validates the assumption that (white) women living in developed countries are not just better off in economic and social terms, but that their ‘developedness’ inoculates their (our) societies against the insecurities that make them vulnerable towards conflict or terrorism. The lack of social-participation, education, and access to basic rights for poor women is assumed to be dangerous for everyone as this ‘creates an unstable environment’,Footnote 76 thereby enmeshing narratives about terrorism and conflict with varied and complex sociopolitical and human rights issues. Laura Shepherd convincingly argues further that ‘this duality of spatiality reinforces a whole series of binary oppositions that construct a particular understanding of security and peace: outside/inside; conflict/peace; backwards/civilised; inferior/superior’.Footnote 77 Table 1 illustrates the gendered discourses present in DFID documents since 1997. It is not an exhaustive list but reflects the discussions in this paper:

Table 1. Gendered representations of women in DFID documents (1997–2019).

The development-security-counterterrorism nexus is therefore characterised by state actors and institutions linking a selection of cross-cutting gendered (and racialised) logics about development, security, and (counter)terrorism that produce a specific type of knowledge about (in)security, development, and (counter)terrorism. Through the presentation of gendered and racialised binaries that situate security and insecurity within different spatial and sexual orientations, the link between the empowerment of women and securing Western society from the threats posed by terrorism is continually reinforced. A tension arises through the adjacent competing discourses of these women as simultaneously lacking in agency in their vulnerability, yet also being integral to ensuring British national security as natural peacemakers. DFID struggled to adequately integrate the complex and often contradictory representations of women in its programming as a result of persisting gender stereotypes, institutional ‘hangovers’, and the integrated development-security-counterterrorism agenda that was far from coordinated. This lack of coordination is a direct effect of securitisation. Maria Stern and Joakim ÖjendalFootnote 79 argue that governments and policymakers often tend to blur together different ontologies of security and development, which means that their policy documents and programmes are often not empirically workable or ontologically sound. Thus, as argued by Laura Sjoberg, securitisation ‘can have the effect of militarisation – changing the traditional categories of security without changing the traditional tools (militaries) used to address what is understood as security’.Footnote 80 Sjoberg's assertion suggests that securitising an issue such as development on the basis of a perceived broadening of what constitutes a ‘security issue’, could potentially heighten insecurity (such as for women) due to the fact that the existing infrastructure might not be adequate to address the newly securitised issues.

Practising the nexus

The War on Terror and the ‘securitisation’ of the development agenda marks a turning point for DFID. Three different policy streams were being pursued at the same time through the development-security-counterterrorism nexus, all of which had linked gendered components that evolved and were practised differently: gender and development; gender and security; and gender and (counter)terrorism.

The first observation to make is that across DFID documents, there is no clear application or use of the term ‘gender’. Often, the term is used synonymously with women, or as a variable. Rarely (but sometimes) gender is understood and practised as a process that considers the structural factors involved. Using gender in the context of men, masculinity, or male-specific challenges, is fairly rare, and also inconsistent. For example, back in 2000, DFID's strategy paper ‘Poverty Elimination and the Empowerment of Women’Footnote 81 references the ways in which men and boys are implicated in the wider gendered environment, demonstrating a clear understanding of how gender is implicated in a matrix of institutions, norms, rules and relations of power and domination. The authors of the paper note:

Choices for women, especially poor women, cannot be enlarged without a change in relations between women and men as well as in the ideologies and institutions that preserve and reproduce gender inequality. This does not mean reversing positions, so that men become subordinate and women dominant. Rather, it means … negotiating new kinds of institutions, incorporating new norms and rules that support egalitarian and just relations between women and men.Footnote 82

Unfortunately operationalising these nuanced observations does not seem to have transitioned seamlessly into practice. The nominalFootnote 83 characteristics of gender have been emphasised in the way gender has been understood, referenced, and integrated into policy and programming, which has done little to shift the institutional logics from treating gender as a variable to understanding gender as a practice. Despite the shift to institutionalise gender mainstreaming into all DFID projects first through the Gender Equality Action Plan (2007)Footnote 84 and then the Gender Equality Act (2014), reforms like this can become more of a tick-box exercise, which sometimes do more harm than good. There is a difference between policies and programmes whose primary focus is to promote gender equality and those where gender equality is not the primary focus, but gender dimensions are mainstreamed into the design. While the commitment to institutionalising gender sensitivity in all development programming should be commended, the implications of not doing gender properly as a result of gaps in knowledge, poor training, or an inconsistent understanding of what ‘gender’ means among practitioners, could mean that programmes could end up being ineffective at best and dangerous at worst.

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) provides a comprehensive – but disappointing – assessment of some of DFID's gender-specific programmes. There are six completed DFID-FCO reviews related to ‘women and girls’ between 2011 and 2021. Out of the six, the review titled ‘DFID's Efforts to Eliminate Violence against Women and Girls’ (VAWG) was the only programme to receive a green flag rating indicating UK aid is ‘making a significant positive contribution with strong achievements of good practice across the board’.Footnote 85 Three key takeaways from this review are that DFID VAWG programming is still very small scale and narrow in scope; the aims and objectives are clear, this is a DFID-owned programme, not joint with the FCO (joint FCO-DFID initiative on VAWG in conflict and humanitarian emergencies is separate to this area of programming)Footnote 86 and the gendered challenges of violence facing women are the primary focus of this programme, rather than being integrated as a result of mainstreaming.

The reviews of the other five gender-sensitive programmes received Amber/Red ratings, signifying ‘unsatisfactory achievement in most areas, with some positive elements’. The UK's ‘Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative’ – an FCO-led initiative, cited as a ‘flagship government programme to tackle sexual violence in conflict zones’ was identified as risking letting survivors down due to a lack of senior leadership, poor strategy, and cuts in funding.Footnote 87 Women and girls were the key focus of this initiative, with ICAI observing that ‘the use of sexual violence against men and boys as a war tactic to humiliate them and damage social relationships’Footnote 88 was not addressed. One of the key criticisms highlighted was ‘The initiative has no overarching strategy or theory of change, and programming has been fragmented across countries and between the three main contributing departments, the FCO, the Department for International Development and the Ministry of Defence’,Footnote 89 which underlines how integrating the FCO-MOD-DFID agendas has undermined rather than strengthened DFID's development programming.

I also examined two ‘peace, security and justice’ programmes where gender was mainstreamed rather than integral to the aims and objectives. The 2018 ICAI report on the CSSF's aid spending is based on 34 projects across six case studies, under multi-agency coordination. The report states that despite efforts such as improving proposal design through a gender ‘scoring system’, the CSSF's ‘commitment to gender sensitivity and to furthering the role of women in peace and security is not yet consistently mirrored at programme level’.Footnote 90 ICAI found that CSSF personnel demonstrated an inconsistent understanding of ‘gender equality’, exemplifying the presence of competing institutionalised gender logics. For some, ‘gender equality’ means ‘ensuring that women are included among police trainees, rather than addressing the security and justice needs of women, girls, men and boys’.Footnote 91 This ambiguity among personnel is reflected at the programming level:

the CSSF has a strong focus on gender sensitivity and furthering the role of women in peace and security initiatives. Gender issues feature in its templates for programme design and reviews. The Fund conducts training sessions on gender issues and has gender experts to advise country teams. However, across our sample, the focus on gender was not always fully maintained during implementation.

ICAI's reviewFootnote 92 of DFID's approach to anti-corruption programming in Nigeria and Nepal concluded that DFID's overall approach to anti-corruption in these areas failed to adequately understand or tackle the ‘high barriers women face in their economic and social empowerment, where decisions are made through personal connections and not democratically’,Footnote 93 and that ‘there appears to be no focus on the impact of corruption on women and girls specifically.’Footnote 94 These reviews clearly demonstrate the disconnect between the strategic level and the programming level and highlight tensions between the Ministerial departments. Furthermore, they demonstrate that the joint FCO-MOD-DFID approach to development and security programming has often disadvantaged the women and girls who were supposed to be at the heart of the initiatives.

The WPS agenda represents another cross-departmental policy agenda, which is also indicative of the UK's integrated approach to development, security and, more recently, counterterrorism policy and programming. The WPS agenda is practised through the implementation of NAPs, which are strategic documents implemented at the country level that outline strategies and programmes for various types of security programming work that aim to address and advance the challenges and opportunities for women and girls in situations of violence, conflict, and peacebuilding. Some examples of this work include civil-military partnerships, law enforcement collaboration, and conflict resolution; in 2018 P/CVE programming was also introduced. Since issuing the first NAP in 2006, these documents have become much more coordinated. Much of the conceptual clarity and strategic evolution is owed to the consistent engagement with civil society practitioners, which has greatly advanced and refined how NAPs are designed. The public consultation process through which each new NAP is drafted is a good example of how collaborative efforts can enhance and evolve knowledge and understanding as a range of women's civil society organisations are given the opportunity to review, comment on and make recommendations about drafts of the NAP before publication. Often these recommendations are directly addressed. For example, in 2017, the London School of Economics WPS Consultation Group was invited to comment on the 2014–2017 NAP and make recommendations for the next one. The Group commented on the lack of attention paid to men and boys and the intersectionality between other social issues such as race, class, and disability;Footnote 95 these comments were subsequently directly incorporated into the 2018 NAP. Similarly, the organisation Gender Action for Peace and Security provided expert opinion and advice from a practitioner approach,Footnote 96 which was also incorporated. The result is that the 2018 NAP is the most comprehensive, most thoughtful and most considered version of all four to date. Its implementation requires close monitoring and evaluation; the halfway point review is currently due.Footnote 97

However, in 2018, the P/CVE discourse was integrated into the WPS agenda for the first time. Despite the overall general improvements in the drafting of the NAP, the document is severely lacking in detail about how the P/CVE agenda would be practised on the ground. The NAP states: ‘women also participate in violent extremism’,Footnote 98 and goes on to say

the links between women, peace and security and preventing and countering violence [sic] extremism are an emerging concern for the international community. As such, meaningful indicators have not yet been developed and data is not gathered systematically. We will work to develop meaningful measures over the course of the NAP period.Footnote 99

It is interesting that the NAP considers women's links with P/CVE to be an ‘emerging concern’ in 2018 when women have been engaged in various aspects of terrorism and violent extremism for decades.Footnote 100 Given that the NAP is situated at both national and international levels, it seems obvious that observations, research, and lessons learned from countries that have had long histories of female perpetrators of terrorism and violent extremism could have been drawn from to develop appropriate gender-sensitive P/CVE programming infrastructure.

Since the passing of UNSCR 2242 in 2015, feminist scholars have heralded caution with regard to integrating the P/CVE and WPS agendas; surprisingly, out of the seven ‘strategic outcomes’, the P/CVE outcome is the only one that does not appear to be systematically subjected to the same external scrutiny or oversight as the others. The implementation guidance note for the P/CVE strategic pillar, published a year after the NAP, didn't elaborate on this either and the annual NAP reports to Parliament published in 2020 and 2021 make minimal reference to ‘CVE’ with the word featuring six times in 2020 and twice in 2021. These observations highlight that the NAP's approach to the development of the P/CVE pillar suggests that a lot of trial and error is still required before actually understanding what works, and what does not and that rolling out programmes that tackle issues related to P/CVE from a gender perspective remains largely unknown.

An examination of a DFID project based in Somalia named ‘SEED II’ aimed at reducing conflict and increasing stability between 2011 and 2014 highlights that designing gender-sensitive security programming that also addresses (counter)terrorism without a sound evidence base or without clear strategic priorities is both ineffective and potentially harmful. The foreword to the SEED II report states: ‘the programme did not have an explicit CVET [countering violent extremism and terrorism] objective at the outset’,Footnote 101 but the introduction states ‘the ToC [Theory of Change] is built on the assumption that there is a causal link between the lack of livelihoods and unemployment and recruitment to violent groups.’Footnote 102 There is already a disconnect between the ToC that is guiding the hypotheses for the project and the foreword that is introducing the project. Furthermore, according to a senior DFID-FCO policymaker, the dual objectives of the project were to better understand whether unemployment was a driver of radicalisation and how does mainstream development work interact with radicalisation and extremism?Footnote 103 However, this was not made explicitly clear from the outset and instead the project set out to improve the livelihoods of farmers and to reduce drivers of extremism (towards al Shabab).

The project contained a gender-sensitive approach, which was based on a series of flawed assumptions about: (a) those who were vulnerable to being radicalised; and (b) the roles of women involved in the process: the project targeted men over forty years old and who had land, and 30 per cent of the project's work focused on women as a means to better understand recruitment to al Shabab. The rigorous analysis of granular aspects of the region's topography, clan structure, and inter-clan dynamics among other things, revealed that this was not necessarily the right way to understand recruitment trajectories on the one hand, or to learn about the roles played by women on the other, stating: ‘the concept of radicalisation and the concept of recruitment … are likely to be different depending on the interest of the individual or group that is being recruited.’Footnote 104 According to the report findings, this is not the demographic from which al Shabab recruits and in an interview with a former senior DFID-FCO policymaker I was told, ‘if you're actually trying to reduce drivers of extremism, you might target young men aged around 15–24 in this case.’Footnote 105 With regard to the focus on women, the review stated ‘from a perspective of enhancing stability … the role of women in recruitment and joining armed groups in Somalia remains poorly understood…the 30% women are as such not likely to contribute significantly to stability’,Footnote 106 highlighting that the assumption about women's roles was likely misplaced and therefore the resources spent on this proportion of the programme were not efficiently utilised. A third assumption was that a lack of economic opportunities drove people to join al Shabab; in reality, very slight evidence was available for this. Rather, the clan structure in Somalia was such that a clan leader would decide whether or not they wanted to support al Shabab and then the rest of the clan would follow.

The review's conclusions indicate two things. First, policy design has to be evidence based: setting out to improve socioeconomic livelihoods while simultaneously pursuing the joint objective of reducing drivers of extremism must thoroughly understand who the vulnerable candidates are as well as how and why they are able to be recruited. The evaluation showed that the secondary objective, to reduce drivers of extremism, had not been properly factored into the design of the programme. Second, given that the objectives of the project were grounded on assumptions about males in a certain community at risk of violent extremism, had a thorough gender analysis had been carried out in advance, this could have revealed the impact on women of such programming aimed at men. Gender-based programming is clearly complex and needs to properly understand the local gender dynamics in relation to the specific problem trying to be addressed. Doing this properly can help ensure DFID and other UK government programming enhances and protects women's equality. Doing it badly has limited impact, or at worst, adverse effects. My interviewee told me that this was the first ever evaluation that looked at a mainstream development programme and tried to see whether it actually had any effect on trying to reduce radicalisation and extremism.Footnote 107 They concluded:

if you are going to say it will reduce radicalisation then you really have to think carefully about the design for that. As DFID was designing programmes, it should factor in an element of ongoing evaluation; the big win would be to understand what role does development play in reducing radicalisation and extremism? We know what this looks like in theory, but no one had really tried to look into this empirically. We can't keep making assumptions.Footnote 108

The issues highlighted through the SEED II review emphasised the importance of evidence-based policy and programming with regard to the gender-sensitive counterterrorism agenda and also highlighted how gaps in knowledge affected and influenced policy outcomes. In 2015, DFID commissioned The Royal United Services Institute (RUSI)Footnote 109 and Sarah LadburyFootnote 110 to research different aspects of female pathways into terrorism and violent extremism. Both papers acknowledged that women's support for violent extremist groups has been overlooked in policy circles with Ladbury observing that

to date, most policy and programme interventions on preventing radicalisation and addressing political and economic grievances have been targeted at men and boys … as more detailed studies become available, these gendered assumptions are called into question. It is no longer possible to ignore women on the assumption that they blindly follow the men.Footnote 111

Integrating gender and counterterrorism programming

The cross-cutting nature of terrorism and violent extremism and its various intersections with gender, therefore, started being conceptualised after 2015 and new discourses about gender and (counter)terrorism began to be reproduced through the nexus as a direct consequence of Islamic State's recruitment of women. In an interview with a former departmental employee, I was told:

Until very recently the national security system has been largely ignorant of the roles women can play [in violent extremism and terrorism]. There was the assumption that women are primarily victims of terrorism. There was no concept that they can be active agents of it … No recognition of the range of roles women can play both as engaging and promoting terrorism as well as the powerful roles women can play in preventing and thwarting terrorism … it was not until the Bethnal Green girls incident that these issues were really highlighted.Footnote 112

These comments demonstrate that despite having engaged with gender-sensitive development and security agendas for over 15 years, there was a clear blind spot among institutional actors in terms of engaging with gender-sensitive aspects and challenges of (counter)terrorism. The blind spot among DFID-FCO-MOD policymakers with regard to considering and responding to women's roles and experiences in (counter)terrorism can be understood as a result of ‘sticky’ legacies of representations of women in international relations, security, and development discourses that are produced through the institutions of the development-security-counterterrorism nexus. These sticky gendered legacies of representations of women demonstrate the saliency of sedimented discourses about women's positions, experiences, and responsibilities in situations of peace, violence, and conflict that remain overwhelmingly focused on women's rights, empowerment, conflict prevention, and victimhood and have been reluctant to expand into alternative discourses that consider women's roles in terrorism and violent extremism. Despite the fact that DFID was a newly established institution, gendered legacies of the past have been continually reinforced by constituent actors and organisations within the nexus, meaning new discourses can only become institutionalised through a transfer of power, whereby hegemonic discourses are destabilised and multiple, new discourses circulate.

The 2017 NAP report to Parliament is the first time that women were referenced in relation to preventing or countering violent extremism (P/CVE) in the context of development and security. The document affirms that women's roles and experiences related to all aspects of violent extremism and terrorism have been overlooked, adding that in October 2017 a round table was chaired on ‘countering violent extremism and the role of gender to begin exploring this area’.Footnote 113 Following the October 2017 round table, a number of documents were produced by different state entities within the nexus that were linked to implementing gender-sensitive (counter)terrorism programming.

The Joint International Counter Terrorism Unit (JICTU) Gender Sensitivity and Counter Terrorism Guidance Note (2018) is the first (and perhaps only) government document that details how to carry out gender-sensitive counterterrorism and CVE programming across the four pillars of the UK's counterterrorism strategy, CONTEST ‘from the outset in policy development and project design and implementation’.Footnote 114 The Stabilisation Unit (SU) documentFootnote 115 is part of a longer, more comprehensive ‘strategic communications “how to” guide’, which has clearly paid a lot of attention to understanding many of the structural gender-specific experiences of consuming and communicating information. Both documents provide a much deeper and more nuanced understanding and awareness of gender functioning in a multifaceted way. For example, the JICTU document provides a high-level framework for practitioners working across a range of counterterrorism activities from community-based programming to intelligence collection and surveillance to more physical security activities such as law enforcement or border security work, guiding them through a gender-sensitive approach, and makes clear that ‘gender’ refers not just to women, but also to men and boys. The SU document similarly expands its understanding of gender beyond that of a variable, which also targets men and women in its gender-sensitive approach to designing counter-narratives.Footnote 116 However, as with the NAP and SEED projects, there is a lack of emphasis on monitoring and evaluation and a lack of clarity around how effective programming has been on the ground or what lessons have been learned from past initiatives.

The 2019 Guidance Note to implementing Strategic Outcome 6 of the WPS agendaFootnote 117 is clearly informed by the 2015 Ladbury paperFootnote 118 but greatly expands its scope both in relation to female perpetrators of terrorism and violent extremism and in relation to female prevention and countering roles. Nevertheless, the examples given about the nature of gendered P/CVE roles are generalised rather than country or case specific and there are no clear observations made or conclusions drawn about women holding positions in civil society or in government that could inform future work for women doing P/CVE in different countries and locations. Furthermore, it interestingly introduces the extreme right wing (XRW) into the matrix. Considering this Guidance Note is specifically aimed at implementing Strategic Outcome 6 of the 2018 NAP, it seems like an add-on that has been included without much consideration given that the NAP itself does not mention XRW violent extremism.

These documents demonstrate a good degree of institutional evolution in the production of gendered discourses by the development-security-counterterrorism nexus. However, as already highlighted, a huge limitation is the lack of emphasis on monitoring and evaluation infrastructure. Furthermore, there is little information about the evidence base that has informed strategic changes in policy and programming which reinforces the issues of conceptual clarity and direction in terms of systematically designing and implementing gender-sensitive counterterrorism programming.

Evaluating the concerns

The post-9/11 strategy to more closely integrate DFID's development programming work with the broader international counterterrorism aims and objectives of the FCO and MOD created a lack of coherence the operationalising of specific institutional agendas produced through the development-security-counterterrorism nexus. This had specific impacts on gender-sensitive programming, which left feminist academics concerned about the nature of the integration of (counter)terrorism and gender-sensitive development and security programming.Footnote 119 Even though the academic researchFootnote 120 has been advancing in both theoretical and empirical examinations of gendered (counter)terrorism, policy has taken a long time to catch up. Fionnuala Ní Aoláin argues that ‘the expansion of WPS to include women in the counterterrorism domain does not mean that women will be included in defining what constitutes terrorism and what counterterrorism strategies are compliant with human rights and equality’,Footnote 121 suggesting that women's involvement is rendered to one of superficiality, akin to the ‘add women and stir’ mindset that many feminists have become so frustrated with. Shepherd has also assertedFootnote 122 that issues concerning practitioner training in designing and delivering countering violent extremism initiatives often fall below par, which could be harmful in developing a comprehensive understanding of complex and conflicting roles played by women in counterterrorism and countering violent extremism. Although these concerns and the trepidation with which many feminist scholars have engaged with questions of counterterrorism are valid, if not addressed, they do have practical consequences. Ní Aoláin asserts

terrorism is not a new phenomenon, and its influence on shaping foreign and domestic affairs has been consolidating … to remain outside is to forfeit the possibility of exercising any influence on the decisions and actions that affect lives of millions of women and girls across the globe … this in turn underscores the necessity of the WPS agenda to speak directly to terrorism and counterterrorism imperatives.Footnote 123

Rothermel similarly asserts that there is ‘a need for feminists to further engage with, shape, and critique the P/CVE agenda’.Footnote 124 Both Ní Aoláin and Rothermel's points suggest that if feminists want to have a stake in shaping the ways that women and gender are understood and practised in relation to countering terrorism and violent extremism, we should not turn away as this has only allowed non-feminist, or masculinist voices to set the terms of engagement thus far. Nevertheless, without the right evidence to substantiate programme design, implementation, and monitoring, and without clear objectives, these programmes could likely target the wrong individuals on the wrong basis, which could be damaging/dangerous at worst and a waste of resources at best.

Civil-society partnerships and institutional evolution

The influence of civil society practitioners is a useful way to encourage institutional evolution through the practice of external actors challenging and contesting institutionalised gendered logics circulating within government. Creating openings for such partnerships brings the concerns and wisdom of non-government experts to the attention of policymakers, ensures critique of hegemonic or institutionalised discourses that often go unchallenged, and allows for an evolution in thinking and practising of gender and security. This process has the potential to transform gendered logics about security, counterterrorism, and development through destabilising institutionalised social logics.

The International Civil Society Action Network (ICAN) is an example of a civil society organisation with which DFID and the FCO have engaged with extensively. ICAN was part of the consultation process to develop the 2015 Ladbury report, which remains one of the only documents to date that systematically examines drivers of female radicalisation. In a research interview in early 2021 with Sanam Naraghi-Anderlini, CEO of ICAN, Ms Naraghi-Anderlini emphasised that it is possible to carry out P/CVE work with a positive approach and many women all over the world are doing just this, ‘I find the whole “instrumentalisation of women” thing very disrespectful’,Footnote 125 she said. She states ‘the narrative of Western scholars and NGOs that claim women are being “instrumentalised” further exacerbates the situation as it denigrates the expertise, innovation and courage of women at the frontlines of the struggle against violent extremism.’Footnote 126 She firmly believes that discourse and practice need to move away from the victimhood lens and to examine ‘how women on the ground were countering and standing up, warning about violent extremism and coming up with their own strategies’.Footnote 127 Her comments emphasise that an understanding of women's agency in different development and security contexts is missing from government-led discourse.

In January 2020, the SU published an analysis by Professor Jacqui True, examining its ‘elite bargaining processes’ project. True argues that ‘the EBPD project renders invisible both gender-based violence and women's agency’,Footnote 128 which demonstrates that without engaging with gender scholars, women's rights activists, and practitioners on the ground, DFID and its key partners will not be able to effectively implement successful gender-sensitive projects that ‘do no harm’. This type of engagement with civil society could transform how government actors design and implement gender-sensitive programming across different types of development-security-counterterrorism programming. A deeper engagement with organisations and individuals with contesting representations of women in relation to violence and conflict may help to fracture the resilience of existing gendered stereotypes at the institutional level.

DFID – now the FCDO – would do well to increase its civic-government engagement to improve and expand institutional knowledge, and ensure that meaningful change can be made with the right evidence to support and legitimise new policy and practice. As I have shown, there appears to be some disconnect between different institutional layers, which has meant that often programming and operations on the ground are out of sync with evidence-based academic research. Furthermore, policies and guidance notes which detail the ‘what’ and the ‘why’ aspects of implementing broader strategies are not always supported with the how, which again, highlights a disconnect between the knowledge available and how it is utilised. Feminist scholars and practitioners continue to highlight that the lack of evidence in terms of how gender-sensitive policies and programmes are being designed and implemented remains a key concern, especially when it comes to instrumentalising and securitising women's rights and (in)security for broader state security objectives.

Conclusion

Richard Jackson has suggested that discourse operates at two levels that require examining and linking: the first operates to understand how texts are interpreted linguistically and the second is to examine how texts and speech acts interact with social processes.Footnote 129 As I indicated in my analytic framework, through a process of intertextual linking, I have examined how representations of women within security, development, and counterterrorism discourses have been institutionalised through the broader ecosystem of security and development actors, that comprise the UK government's development-security-counterterrorism nexus, over a 23-year period. The purpose of this article was to examine DFID's institutional evolution over its tenure, using both feminist institutional analysis as well as discourse analysis to reveal how and where women and gender have become emphasised and represented in relation to counterterrorism and countering violent extremism (and where they have been omitted).

My analysis first explained the theoretical aspects of institutionalising gender, counterterrorism, and development discourses in DFID's policies and practices. I subsequently examined how counterterrorism discourses became institutionalised within development policies and programming agendas, and I explained how DFID moved from being a peripheral government department to being an integral piece of the security architecture. Finally, I traced the contours of women's representation in discourses and practices of the development-security-counterterrorism nexus. My findings conclude the following.

First, the gendered development-security-counterterrorism nexus is operationalised through multiple institutional spheres across various constituent elements and through a variety of discursive layers. Despite some clear efforts to bring nuance, depth, and insight into shaping discourses about women, gender, and the development-security-counterterrorism nexus, tensions exist between different constituent elements of the nexus, demonstrating a lack of coherence and overall clarity not only through the nexus, but also within the institutions themselves. The joint FCO-DFID-MOD approach to doing development work that broadened the scope for women's security issues, prioritised the security-oriented cultures and interests of the FCO and the MOD over DFID's development priorities, leading to issues of practitioner training, conflicting understandings of ‘gender’ and lack of evidence informing policies and causing confusion; all these issues need to be addressed if HMG is to implement more wholesome, informative, and considered long-term responses.

Second, women and gender still tend to be used interchangeably, but recent documents (published since 2017) appear to be shifting in their conceptualisation of gender to include men, boys, and masculinity; structural gendered issues faced by men and women in relation to violence, extremism, and terrorism are being discussed in these documents more frequently. There is still a distinct lag in terms of where policy is and where feminist academic research is on these issues, but institutional shifts take time to materialise; the learnings from the 2015 research commissioned by DFID were only really implemented onwards from 2017.