Introduction

There is a long-standing assumption that effective dialogues are those with a wealth of politically powerful attendees. However, some high-level dialogues are perceived as performative rather than functional or as ‘talk-shops’ where a lot is said but little accomplished.Footnote 1 Instead, more impactful policymaking is said to occur in other locations, such as private or bilateral meetings. This perspective doesn't explain why some of these forums endure and thrive and others do not. Moreover, the conditions that allow for some of these forums to be more effective at fostering regional dialogue than strictly formal or informal processes with the same goals are unexplored.

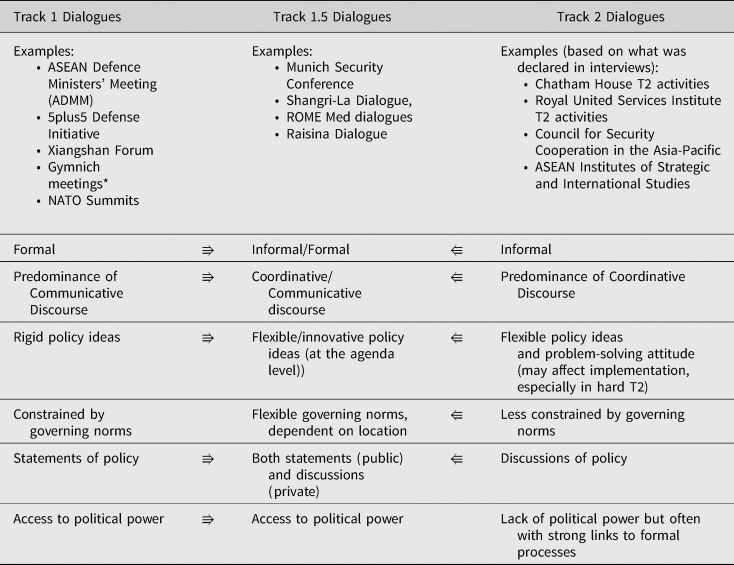

Against this background, the purpose of this study is twofold: first of all, we seek to scrutinise the potential of Track 1.5 processes in contrast to Track 1 (T1) and Track 2 (T2), by unravelling the complex factors rendering specific T1.5 security dialogues more relevant and enduring than other types of regional security dialogues. This is argued by offering a clarification about the three multitrack forms of diplomacy (see Tables 1 and 3).

Table 1. Type of track dialogues and discourse.

*Source: Dalia Dassa Kaye, ‘Rethinking Track Two diplomacy’, in Talking to the Enemy: Track Two Diplomacy in the Middle East and South Asia (RAND Corporation, 2007), pp. 6–8.

While a diversity of dialogues, seminars, or conferences dominated by security issues do exist, only a few of these meetings have become stable events and research on these phenomena remains extremely difficult in terms of ‘continuity of access’. We believe that it is mainly for this reason that T1.5 diplomacy represents a practice that has not attracted – nor asked for – extensive academic attention.

Secondly, we try to meet this challenge and propose an insightful examination of two case studies that are broadly considered to be successful security forums in Europe and in Asia, the Munich Security Conference (MSC) and the Shangri-La Dialogue (SLD), which are intended to serve as exploratory but significant examples of the multitrack diplomacy context and of security practice.

In this article, we borrow from heterogeneous discourse approaches as a theoretical background for analysing T1.5 security dialogues. The added value of adopting a discourse perspective relies not just on the acknowledgement of the reciprocal relationship between ideas and institutions,Footnote 2 but also in the assumption that discourse can produce the social reality it defines. Not only elite discourse produces individual or joint policy practices.Footnote 3 The focus on discourse better explains the role of agents as non-state actors, and individuals, in international politics as legitimate players within regional institutions.Footnote 4

Within this frame, we further develop the concept of discourse first by defining the concept of ‘discursive space’ and then introducing the components of the quality of such space. Indeed, assuming that creating a location for dialogue is not enough to ensure its success, we argue that it is the quality of the discourse that occurs in such spaces that determines which forums will attract politically relevant audiences, earn credibility, gain legitimacy as locations of substantive policy outcomes, and ultimately be considered effective.

We suggest that the effectiveness (ultimately the success) of a dialogue, that is to say its ability to inform and progress the practice of international security, is determined in large part by what we call the quality of its discursive space. As such, the political authority of a dialogue's attendees, while certainly important, is only one of the three factors we identified as being relevant components of our independent variable, ‘the discursive quality’, the other two being: (1) the type(s) and content of discourse used, and (2) the level of formality or informality of the dialogue itself. The necessary condition for a dialogue to become or remain effective has to be found as a balance among these factors.

Out of all forms of regional security dialogues, the focus of our analysis is on T1.5 security dialogues as we found that they can be the most likely venues where one can find a balance among these factors. T1.5 dialogues have not received the same level of scrutiny as their formal (T1) or informal (T2) counterparts. There is a significant empirical gap to be filled, given the little available literature focused on their analysis. This is particularly true on the European side, where there has been a longer and more robust history of effective T1 processes, with more attention possibly dedicated to the role enacted by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), its practices of socialisation in post-Cold War Europe,Footnote 5 and the spread of security communities.Footnote 6 We hypothesise that this has reduced the attention on T1.5 processes. Even so, informal meetings have played important roles as venues of socialisation in less formal arenas,Footnote 7 and have had the ability to impact regional security governance through providing important ideational and institutional blueprints.

A clarification about the two tracks of diplomacy (Track 1 and 2, or T1 and T2) and of the hybrid model (Track 1.5 or T1.5) is therefore introduced in the next part of this article. Indeed, non-state actors regularly organise T2 and occasionally T1.5 discursive spaces, where actors can operate outside of restrictive regional norms. The results are opportunities for security actors to ‘think outside the box’ and to ‘address security issues not yet on governmental security agendas’.Footnote 8 This is particularly important in regions like the Asia-Pacific where security issues are varied, complex, and with a growing role of non-traditional actors filing in the governance gaps in key issue areas.Footnote 9 The quest for informal spaces facilitates a ‘habit of dialogue’ and consensus-building,Footnote 10 as well as the ‘relationship maintenance’ of recent partnerships.Footnote 11

Ultimately, cross-regional comparisons of Track 1.5 regional security dialogues are scarce if not entirely absent. We believe that there are valuable lessons to be learned in determining what drives the creation of these unique types of dialogues, why they exist across vastly different political environments, and how single factors can determine their success and subsequently, their longevity. With the aim of improving the understanding of the role of T1.5 diplomacy in the practice of international security, in what follows, we clarify the research design and methodology of our analysis. We then introduce the theoretical framework and proceed with the analysis of the selected cases.

Research design and methodology

In this article we adopt a comparative approach in order to provide one of the first cross-regional comparative analysis of T1.5 security dialogues. In order to investigate regional security dialogues – a rather unexplored phenomena – we rely on a mix of techniques that will be further examined below: previous research on foreign policy think tanks, participant observation of seminars and conferences, scholarly publications and other public outputs, and interviews with dialogue participants and organisers specifically aimed at clarifying those details that were unavailable through public sources like conference leaflets. Then, we faced the problems of incorporating and interpreting diverse and non-linear data that were gathered during this analysis. Our empirical analysis is not entirely deducted from pre-existing categories, though it borrows from the discursive argument and it introduces new elements aimed at reducing the complexity of our field of analysis. The selected case studies are analysed in light of the three identified factors – as highlighted later in this article – that we hope are a welcomed addition to the cases that support the discursive argument in the analysis of international politics.

Case selection and time period

After preliminary research, we selected the Munich Security Conference (MSC) in Europe and the Shangri-La Dialogue (SLD) in Asia in order to allow a comparison of two cases sharing similar features like their status as Track 1.5 security dialogues and their history of providing high-quality discursive forums in their respective regions. Indeed, both forums enjoy unprecedented legitimacy as governing spaces hosted by non-governmental organisations. It is also worth mentioning that, albeit disputable and merely descriptive of a universe of cases in which we were interested, the 2018 survey of the best think tank conferences conducted by the Think Tank and Civil Societies Program at the University of Pennsylvania, ranked the Shangri-La Dialogue and the Munich Security Conference among the top four in the world.Footnote 12 These rankings are identical to the previous year's, and the MSC was ranked as the overall best think tank conference between 2014–16, while the SLD was ranked third during that time.

We conducted an in-depth study of these two typical cases,Footnote 13 which are broadly considered to be successful security forums in Europe and in Asia, and we compared them along three main qualitative factors that we have identified as being explanatory of their success. Indeed, the MSC and the SLC are significant examples of successful mechanisms in the global context of multitrack diplomacy and security practice. These cases are in contrast, for instance, with forums like the ARF Experts and Eminent Persons (ARF EEP) group, a T1.5 mechanism that is considered rather stagnant,Footnote 14 as it lacks high-quality discursive space as defined in this study. In other words, in this analysis we suggest that, among potential other causes, the ‘quality of the discursive space’ holds explanatory power in respect to dialogue effectiveness (that is, success).

We acknowledge that the concepts of ‘effectiveness’ and ‘success’Footnote 15 are problematic to quantify in terms of ideational and policy change. We use the concept of effectiveness or success of a dialogue – that is, its ability to ultimately inform and progress the practice of international security – to indicate that some dialogues are persistent in: (1) terms of longevity; (2) their ability to attract and retain high-level participants and; (3) being used as locations of significant foreign policy text exchange.

‘Text’ alone may simply refer to knowledge in the form of factual content, but here we are interested in when and how text becomes meaningful and influential, affecting policy debates that occur within the venues under analysis. We argue that text becomes meaningful when it acquires intertextuality, that is, when it is constructed within different possible modalities of authority and knowledge.Footnote 16 When foreign policy text is linked to authority it is transformed into foreign policy ‘discourse’ (which may have Vivien Schmidt's coordinative and/or communicative functions, as we argue in the article). Foreign policy discourse can vary in connection to formal or informal institutions of policymaking (producing official or unofficial discourse). Below, we associate different types and functions of discourse to better explain the three multitrack forms of diplomacy.

Summing up the previous considerations, in this study we understand the ‘quality of discursive space’ to be based on a set of three qualitative factors (level of formality, types of discourse used, and access to governing authority), that were either derived from existing literature or deducted from the empirical analysis and pushed further to be developed into the framework proposed here. We also offer a first attempt to navigate the complex phenomena of security dialogues in Europe and in Asia. Furthermore, we found the qualitative approach more advantageous ‘in studying complex and relatively unstructured and infrequent phenomena that lie at the heart of the subfield’, ‘especially the intensive study of one or a few cases’.Footnote 17 The selected timeframe for our analysis is from 2009 to 2019, which brackets the end of the global financial crisis to just prior to the outbreak of COVID-19.Footnote 18

Data gathering and analysis

Empirical data was generated via a combination of fieldwork trips through Asia and Europe in the period between 2011 to 2019, which involved both the collection of interviews, and direct participation in seminars and dialogues. Interviews were conducted with participants and organisers of regional security dialogues, dialogue participants, and think tank staff.Footnote 19 In Europe, four interviews were collected with possible competitors of the MSC in early 2018, specifically with organisers of the Rome MED dialogueFootnote 20 and with the Italian representative of the ‘5+5 Defence Initiative’.Footnote 21 An email interview was then conducted with the Chief Executive Officer of the Munich Security Conference (MSC), Benedick Franke in June 2018.

The interviews are listed in Table 2. Interviews with dialogue participants and organisers were specifically aimed at clarifying details that were not available through public sources. Text from interviews is not quoted to prove something but it is intended to fill a void of information about the dialogues, due to the difficulty of access for an independent uninvolved researcher. As such, we do not reify the opinions of the interviewees as fact, but rather we use them as internal sources for better understanding the conference setting, format, participants, and organisations.

Table 2. List of interviews.

Note: *The role refers to the period of time when the interview was carried out. Since the interview, the interviewee/s might have changed roles or employment.

In addition to more recent interviews, further preliminary information was gathered from a total of 26 semi-structured interviews conducted between 2013–14 in Europe for previous research on foreign policy think tanks in Italy, the UK, and Germany. These were useful for clarifying the difference existing in the practice of T2 and T1.5. Moreover, other information was collected from more than a dozen respondents who were interviewed under ‘Chatham House rule’ during one author's four-month visiting period at the European Institute for the Mediterranean in Barcelona in 2016.Footnote 22 The latter is worth mentioning because it provided further contrast to the forums analysed in this article, as it is different from T1.5 or T2 platforms that only involve researchers and experts, with little or no direct participation of key policymakers. In Asia and Australia, a total of 16 interviews were conducted between 2011–12.Footnote 23

Additional information was gathered through official documents published by state governments and regional organisations, as well as public outputs by non-state actors, think tanks, websites, and scholarly publications. Overall, we stopped collecting data when we felt that further information no longer provided additional value for the scope of our analysis.

Theoretical framework

Discourse approaches: The state of the art

The existence of comparative analyses of Track 1.5 processes has been largely overlooked.Footnote 24 There is no common understanding of what theoretical framework may best fit the study of this phenomenon. Essentially, realism struggles to explain the existence of the political space occupied by Track 1.5 processes, while constructivism and new institutionalism have made some progress with the ‘turn to ideas’,Footnote 25 which acknowledges that ideas can guide institutional change by determining interestsFootnote 26 and informing institutional responses. Still, these theoretical approaches have struggled to account for certain ‘idea’ actors in international relations, particularly those operating in the opaque space between or across the boundaries between formal and informal political spaces.

Thus, we have grounded our argument in the broader literature on discourse approaches, and we argue that discourse, and specifically foreign policy discourse, is central to analysing T1, T2, and T1.5 processes (see Tables 1 and 3). As already observed, foreign policy discourse can vary in connection to formal or informal institutions of policymaking, by producing official or unofficial discourse. Different types and functions of discourse also exist.Footnote 27 Yet there is still no ‘best’ way to study discourse.Footnote 28 In international relations, it's been acknowledged that a varied collection of conceptual frameworks and analytical lenses of discourse approachesFootnote 29 exists and cohabit.Footnote 30 Some scholars have studied the discursive approach and ‘the power of words in IR’ in order to find alternative explanations to the changing attitudes towards environmental matters, like whaling, when it was clear that mere material interests were not helpful in explaining change.Footnote 31 Much earlier, environmental politics in the Mediterranean provided a strong case for explaining the role of epistemic communities. Footnote 32 Discourse approaches have become central to the explanation, for instance, of case studies involving identity conflict, peacebuilding, postconflict contexts or (in)securities caused by the ‘War on Terror’.Footnote 33 Scholars like Katja Freistein have suggested reading the ASEAN Charter signed in 2007 as a ‘discursive monument’,Footnote 34 acknowledging that ‘new speaking positions and new discursive coalitions that build on them could emerge and contribute to questioning existing hegemonies and pushing their own projects’.Footnote 35 More recently, Stéphanie Martel examined how in the ASEAN context that discursive practices ‘have allowed NGOs to challenge, disrupt, and to some extent reshape ASEAN's identity as a security community in the making’.Footnote 36 These approaches may all be classified as constructivist in the broad sense that ‘they theorize and investigate the co-constitutive relationship between agents and structure, text and context, albeit with differing assumptions on the degree to which agents are masters of discourse’.Footnote 37

Table 3. Dialogue tracks and their respective characteristics.

*Source: See: {https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/fac/2019/08/29-30/}.

Discursive institutionalism (DI), also known as the fourth institutionalism, is part of this broader set of discourse approaches but has certain characteristics that make it a distinct strand. First of all, DI not only acknowledges the complex interaction between ideas and institutions, but it recognises that these interactions are managed and influenced by agents.Footnote 38 Indeed, DI conceptualises discourse as inclusive not only of the ideas being conveyed but how ideas are embodied, how they are communicated, where, by whom, and in what way: ‘DI simultaneously treats institutions as given (as the context within which agents think, speak, and act) and as contingent (as the results of agents' thoughts, words, and actions).’Footnote 39 This opens up an analytical space where ‘idea actors’, particularly those not overtly connected directly to existing power structures like non-state actors, may act as legitimate political actors. It is also significant because institutions outside of the state structure (and without state oversight or legitimacy) can also provide the discursive space where discourse is framed. Adapted from Schmidt's discussion about ‘spheres of discourse’,Footnote 40 discursive spaceFootnote 41 is a location where discourse – the interactive process of conveying ideas – occurs.Footnote 42 The importance of discursive space is bound to the study of multitrack diplomacy, as examined in the next paragraph.

Determining the quality of discursive space

In this article, we argue that the quality of discursive space enables the construction of an effective dialogue. Below, we have identified three factors that we hypothesise play important roles in determining the quality of discursive space:

(a) The level of formality (or rather, informality);

(b) The types of discourse used;

(c) The access to governing authority.

Each of these factors functions in a delicate balance with the other two, so that the overall quality of the discursive space is not found in the individual strength of each factor, but rather in the balance of their relationships to each other.Footnote 43 In Table 3, one can see how T1.5 dialogues are able to carve out a political space between T1 and T2 that encompasses the most discursively valuable aspects from the other two types of dialogue, creating a unique balance between the two.

On one side of the spectrum, T1 is known for its formality, rigidity of processes and governing norms, and strong governing authority. On the other end of the spectrum is T2, which is largely informal and less constrained, with more politically challenging if not even innovative ideas, but lacking direct political power. In the middle ground cultivated by T1.5 organisers, there exists an overlap where the strengths of both tracks can be exploited without succumbing to their accompanying weaknesses.

Levels of formality

Formality is defined broadly by how ‘strict’ a dialogue is in terms of norm adherence, openness to the public, its official status (formal or informal), the political role of attendees, and the dominant type of discourse used (see factor B). It also refers to how the dialogue is structured in terms of agenda, interactions between participants, and the availability of unscheduled time for attendees to hold their own private meetings.

In Southeast Asia, consensus-based decision-making, non-confrontation, and non-interference in domestic politics are the preferred governing norms. These norms place constraints on what issues can be discussed, how, and by whom.Footnote 44 Formal dialogues in the region are also very structured and offer little opportunity for the inclusion of new ideas or political actors. As a result, the higher level of formality has resulted in a lower potential for high-quality discourse.Footnote 45 For these reasons, some formal processes, such as ASEAN and the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) in Asia have been labelled as ‘talk shops’, which have struggled with stagnation and have suffered a subsequent lack of state support.Footnote 46 Under the Bush administration, Secretary of Defence Condoleezza Rice skipped the ARF twice,Footnote 47 which, in turn, encouraged several other country's ministers to forgo attending or to depart early.Footnote 48

Similar dialogues exist in Europe, where certain events are predetermined governmental initiatives. The public aspects of the Munich Security Conference (MSC) or of the MED Dialogues in Rome (not the bilateral meetings), for instance, largely fall in this type of format. These forums are often restricted by largely predefined outcomes (usually in the form of a joint memorandum or letter of intent), and fixed agendas and schedules restrict opportunities for the introduction of new ideas, deliberation, and debate. The resulting dialogues offer little more than performance spaces where government officials can exploit the available discursive space to advocate for and consolidate their narratives.Footnote 49

It was in determining the impact for formality on dialogues where our interviews with T2 and T1.5 processes proved extremely beneficial in clarifying the practice and value of each track. In contrast to the T1.5 forums analysed later in this research, three UK think tanks openly identified themselves as participating in activities related to ‘Track 2/unofficial diplomacy’ activities, as did two in Germany and one in Italy.Footnote 50 The settings provided for unofficial diplomacy activities of the surveyed think tanks were intentionally removed from the media spotlight and not meant to be under scrutiny. According to an interview collected at Chatham House in London in 2014: ‘The Cabinet office sometimes relies on Chatham House, particularly in case of crisis, as a place where some conversations can be facilitated.’ The need for discretion was more explicitly the position of the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) in London, relative to meetings with North Korea.Footnote 51

One of the interviewees at the RUSI referred to these activities as ‘cultural diplomacy’, while another researcher at RUSI says: ‘We can work in more informal settings. This can also mean being used by governments. They have realised that think tanks can be used as a channel for unofficial diplomacy.’ Interviewees in Asia shared similar experiences, in that Track 2 was there to provide informal input to T1 and to act as hosts, but that the success of policy or ideas was strictly reflected by the success of the T1 process (ID12–13).

In sum, unofficial diplomacy or Track 2 includes all the activities that some think tanks may carry out to support bilateral or multilateral meetings between different players relative to political or conflict issues, behind closed doors, away from media attention, and with no expectation of acknowledgement. This is different from the Track 1.5 forums analysed later on in this research, as these actors take a more active role in the discursive process aside from providing a location for dialogue.

The ideal balance of formality appears to exist at the confluence of strictness and structure. Structurally, for a dialogue to be effective it needs to be well planned but not rigid. It requires flexibility in its agenda and format, and for attendees to remain diverse in their political ideas and approaches. It also needs to provide participants with opportunities to engage in coordinative discourse, which should also translate in giving participants the chance to have some time off the schedule to build or strengthen relations. There is a direct relationship between the level of strictness observed by a dialogue and the type of discourse that occurs. Strictness equates to communicative discourse, where acts are mostly performative, and innovative or challenging ideas are not encouraged. The less strict a dialogue is, the higher the propensity for coordinative discourse, which is more deliberative in nature.

Discursive types

The second factor influencing discursive quality concerns the types of discourse used. There are two types of discourse: communicative and coordinative.Footnote 52 Communicative discourse is the to whom of discursive institutionalism, and is used to transmit policy and programmatic ideas to the public and legitimise policy decisions.Footnote 53 It is most often used in situations where policy positions are well defined, the discourse is comparatively unreflective, and the participants are limited in their ability to alter their ‘official’ positions.

The other type is coordinative discourse, which occurs between policymakers, experts, and various stakeholders (like business leaders, for instance). Coordinative discourse is the ‘what’ of discursive institutionalism, and it is used to develop policy ideas and share understandings of current policy issues.Footnote 54 This type of discourse is much more deliberative and often occurs among and between actors who hold less-defined policy positions, are more reflective of alternative policy options, and are open/able to alter policy positions.Footnote 55 Due to the elite nature of participants, coordinative discourse is less public and occurs largely in policy circles, across political networks, within epistemic communities, or via advocacy coalitions.Footnote 56

As Nicola Jo-Anne Smith pointed out, in order to be an effective tool of political influence, discourse must perform a variety of functions, including providing focal points, presenting an idea, developing it, identifying its necessity and appropriateness, and persuading elites of its necessity and legitimacy.Footnote 57 This requires the use of both types of discourse, meaning not only what is said, but to whom and in what manner. Most dialogue processes contain both communicative and coordinative discourse. However, coordinative discourse is the most significant for policymaking as it is used to introduce new ideas, as well as deliberate and disseminate them among policy elites. The more coordinative discourse taking place at a dialogue, the more potential the discursive space has in terms of producing policy-relevant outcomes.

Access to governing authority

A third factor of high-quality discursive space is access to governing authority. Access is the operationalised notion of the to whom in DI, and can be both tangible (participants are government officials or have direct access to such officials) or intangible (participants exercise political power through other means, such as media influence, ideational leadership, and funding). Regardless of their source of power, it is important for dialogues to have participants that have the prestige and reputation to authorise their resultant policy activities.Footnote 58 Without access to the actors who can implement policies, ideas for new or improved policies will not be transmitted, regardless of their quality.

However, it is important to underline that the process of knowledge transfer described in this context is rarely coercive. In expert-to-policymaker relations, it is the policymaker that must be willing to hear and, then, follow the expert advice. In high-level forums, experts need to be considered as an already qualified interlocutor to take part and to have the chance to give their contribution. In many instances, ‘government officials do not want to speak, they want to listen and let the scholars speak’ so they can access new information (ID8). Being heard though, is not at all a direct consequence of access. Access is not a sufficient condition to convey ideas. On the contrary, pressure may exist from the policymaker's side to make sure that expert views are adjusted to the governmental line. This ‘autonomy dilemma’ occurs when non-governmental institutions face the difficult choice between facilitated access to policymakers but at the reduced autonomy and the ability to produce critical policy analysis.Footnote 59 This is where the other two components (formality, and diversity of discourse) come in, and often where the distinction between high-quality and low-quality discursive space can be seen.

In what follows, we apply the proposed framework in order to analyse the case studies on the bases of the three identified factors: level of formality, types of discourse, access to governing authority. In turn, this aids in identifying why some meetings have thrived while others have stagnated.

Security dialogue(s) in Europe

While there is well-established literature on the use of expert knowledge in decision-making, especially related to environmental, health, and migration related issuesFootnote 60 there are limited references on the role of Track 1.5 security dialogues in Europe. These practices have only progressively become institutionalised within single national entities, as different political contexts have not always set the right incentives for cooperation between non-state actors and policymakers in the past.Footnote 61

Despite these limitations, the Munich Security Conference (MSC), founded in 1963, is not only the oldest T1.5 Forum in Europe, but it still represents the European scene in the security domain. The MSC actually predates the provision for setting up a Council of Foreign Ministers and a Political Committee to give a foreign policy dimension to the nascent European Union, as these were laid down in the 1973 Copenhagen Report.Footnote 62 Other, more recent ‘newcomers’ in the European scene are the Rome MED Dialogues (started in 2015), and the Stockholm Security Conference (SSC), which saw its very first events in 2016, but has a more local outreach.Footnote 63 On the contrary, the previously mentioned Euro-Mediterranean Study Commission (EuroMeSCo), established in 1996 but seeing new life in 2015, differs from the previous because participants are mostly researchers and experts (see Table 4).

Table 4. Security events in Europe by longevity, type of participants, and topics discussed.

Differently from the other forums, the MSC is the only one that has existed for more than fifty years, attracting the presence of world political leaders and whose topics of discussion are broad enough to allow for the coexistence of different types of discourse.

The Munich Security Conference (MSC)

According to many observers, the MSC has been the ‘window’ through which contemporary security culture in Europe can be viewed.Footnote 64 While the Conference is no longer the only security event in Europe, it remains the oldest and possibly the most relevant. Like the SLD in Asia, the MSC possesses all of the components we have identified for a high-quality discursive space: access to governing authority, several levels of formality, and tries to represent an abundance of diverse ideas. Founded as ‘a forum that brings together politicians, diplomats and defence officials from around the world for talks on global security policy, the MSC's stated goal is to provide a location for ‘open and constructive discussion about the most pressing security issues of the day’.Footnote 65 Also, the MSC has been the premier gathering each year on NATO security issues: ‘Munich is still the jewel in the crown of the international security conference circuit and the one that is guaranteed to make headlines’,Footnote 66 according to the former Danish premier and NATO Secretary-General, Anders Fogh Rasmussen.

The Munich Security Conference as a discursive space

Despite elite participation, the MSC is comparatively non-hierarchical in nature, or, at least, efforts go in that direction. Large entourages are not permitted in the hotels, with the attempt of reducing the ‘bubble’ around policymakers, and making them more approachable. Furthermore, seating is alphabetical as opposed to hierarchical, which is used by conference organisers to encourage maximum interaction among participants (ID5).

Levels of formality

In terms of formality, the MSC is structured like a conference with speakers, panel discussions, and lunches with specific topics and attendees. However, ample informal spaces are planned, allowing for the creation of less rigid interactions. It also offers off-record and invitation-only sessions (see, for example, in 2017 there were private sessions on global surveillance, cyber security, and OPEC and oil).Footnote 67 Each of these sub-fora are specially designed to provide informal discursive space, welcome new ideas, and foster non-standard access to policymaking authority.

In the MSC all types of participants move between different levels of formality. Unlike more formal dialogues and other high-level meetings in Europe, ‘the character of the MSC does not force political leaders to demonstrate unity’ as it neither aims to ‘produce a final communiqué nor aims to formulate concrete policy’.Footnote 68 Instead, the MSC offers a mix of formal and informal, as well as public and private venues for the discussion of security ideas. This mix of formal and informal fosters both communicative and coordinative discourse and the free expression of ideas. Participants take advantage of the relatively low levels of formality to engage in ‘open and frank’ exchanges of views and have given the MSC a reputation similar to that later considered a defining feature of the SLD. Apparently, conference participants feel able to ‘talk about the current difficulties between allies or to openly confront the prevailing orthodoxy’.Footnote 69 In this context it is worth mentioning as an example the famous speech given by Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2007 that started with the statement:

This conference's structure allows me to avoid excessive politeness and the need to speak in roundabout, pleasant but empty diplomatic terms. This conference's format will allow me to say what I really think about international security problems.Footnote 70

The Conference dialogue's format offers an opportunity for frank criticisms. While this may be true also for other conferences, it is the resonance of the MSC itself and the levels of participants that makes this quite unique. In the same speech against the unipolar model emerging after the Cold War, President Putin went on to both outline the perspectives of his country and strongly criticise the United States and NATO. The format of public statements has been copied by newcomers such as the MED Dialogues in Rome (ID1). The shortcomings of public statements of this kind are evident and depend on their performative nature, but considered in context the strict filtering of more formal dialogues is avoided.

In other occasions at the MSC, the value is not in what is said, but instead by what is left unsaid. For instance, at the first MSC after Donald Trump's inauguration, multiple high-level speakers focused on the need for unity, coherence, and adherence to shared values, with, as observed by Washington Post reporter Anne Appelbaum, no mention whatsoever of the new elected US President Trump. The implications of this omission were clear to those in attendance: that the US president himself was a threat to the Western Alliance.Footnote 71 At the same time, several other members of the US delegation openly criticised the new American President's policies. Conference Chairman Ischinger noted that the ability of different components of a sovereign government – publicly debating and fighting ‘it out in a democratic manner’ – was a testament to the open venue provided by the MSC.Footnote 72

Types of discourse

In addition to offering a clear opportunity for communicative discourse, the MSC also offers both formal and informal behind-the-scenes opportunities for coordinative discourse. Supplementing the main sessions are additional discursive opportunities such as public panels, recently added break-out sessions (which are private), as well as the ‘women's breakfast’, the CEO lunch, and other spaces at the ‘margins of the conference’.Footnote 73 Apart from the main hall, there are indeed many different bilateral affairs rooms set up to host the more than 1,200 bilateral meetings held during the weekend of the MSC. There are also informal and private breakfast meetings and invitation-only lunches. In 2017 alone, there were 150 side events at the MSC. The current Chief Operating Officer of the MSC, Benedikt Franke, noted that with hundreds of confidential side events and thousands of organised bilateral meetings, ‘I do not think you will find more open and frank debates anywhere else’ (ID5).

It is important to underline that ‘the character of the MSC does not force political leaders to demonstrate unity’ as it neither aims to ‘produce a final communiqué nor aims to formulate concrete policy’.Footnote 74 Instead, as former Vice President of the United States Joe Biden wrote, ‘Munich is the place to go to hear bold policies announced, new ideas and approaches tested, old partnership reaffirmed, and new ones formed … Munich connects European leaders and thinkers with their peers from across the world to have an open and frank exchange of idea.’Footnote 75

Access to governing authority

An essential characteristic of effective dialogues is their ability to endure over time, and the MSC has certainly done this. The Conference has a proven capacity to adapt, first with its ideational agenda and then its membership after the end of the Cold War.Footnote 76 The Conference also seeks to increase female participation to 25 per cent (ID5). Its subsequent gains in diversity in terms of including more participants from differing professional backgrounds and political views has kept the conference contemporary.

The MSC has also worked actively to ensure that it ‘brings together a mix of political leaders, government officials, military officers, academics, think tankers and journalists who focus on security issues’.Footnote 77 The MSC has added more participants in the form of ‘CEOs, human rights activists, environmentalists, and other leaders representing global civil society’.Footnote 78 Even so, the Conference has also been criticised for including ‘dictator's henchmen’ alongside the more preferable ‘free citizens’.Footnote 79 Though the Conference still receives criticisms for not being aggressive enough in its adaptation to the changing security landscape, its agenda has evolved beyond ‘hard security’ topics to include so-called ‘non-traditional security’ issues such as climate change, financial insecurity, and cybersecurity.Footnote 80

Lastly, the discursive space provided by the MSC offers substantial access to governing authority. In 2012, the then UN Ambassador to NATO commented that the MSC was essentially the ‘Oscars’ of security policy.Footnote 81 In 2013, ‘more than sixty foreign and defense ministers were in attendance, along with eleven heads of state and government’.Footnote 82 The MSC is so influential that it provides an ad hoc office for the host-country delegation of the German Foreign Office, which coordinates the appointments for the German Foreign Ministers (ID5). Overall in 2017, around forty places were reserved for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; twenty-five for serving prime ministers or presidents; and ninety places for members of parliament. In addition, the conference has hosted the UN Secretary General, vice presidents of the United States, Nobel laureates, and in any given year one-tenth of the full US Senate has been known to attend.Footnote 83

With this calibre of policymaker in attendance, access to governing authority is available for the increasingly diverse contingent of ideas actors who attend the MSC. Selected by Ambassador Ischinger for ‘their level of contribution to the debate or relevance of their work to policy and politics’, the numbers of academics, NGOs, and civil society actors in attendance has steadily gone upFootnote 84 in both number and influence.Footnote 85 The increase in NGOs reflects ‘the increased presence and influence of NGOs in international politics’ (ID5). Together with a more dedicated presence on social media, these are clear signs of an attempt by the MSC to be more inclusive than in the past.

Security dialogue(s) in Asia

The first regional governance organisation in Southeast Asia was the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) founded in 1967. Starting with just five members, ASEAN now includes all the nations of Southeast Asia and engages with the rest of the region via the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF)Footnote 86 and the ASEAN Plus processes. A series of Track 2 processes evolved alongside these organisations and assumed the role of informing Track 1 through research and policy analysis.Footnote 87 For instance, the ASEAN-Institutes for Strategic and International Studies, established in 1988, works alongside ASEAN and is tasked with providing policy advice as well as aiding in regional coordination and cooperation.Footnote 88 The Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia-Pacific (CSCAP) holds a similar role with the ASEAN Regional Forum.Footnote 89 However, these processes, both T1 and T2, were established ostensibly for foreign ministers.

As late as 2001 there was still no regional security dialogue in Asia for defence ministers, despite a growing list of regional security threats.Footnote 90 Separate attempts by both the US Secretary of Defense and the Thai Defense Minister to establish such a gathering were unsuccessful.Footnote 91 Ultimately, it was a British think tank, the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), which established the first high-level defence ministers’ dialogue in Asia as a response to the ‘striking gap in the roster of inter-governmental meetings in the Asia-Pacific region’.Footnote 92 This means that defence diplomacy in Asia started in the unique political spaces of T1.5 diplomacy: this is potentially indicative that existing processes at the time, both formal and informal, lacked some of the essential factors necessary for successful security discourse.

The success of the SLD has led to other defence dialogues, many of which attempt to take on its unique characteristics. ASEAN established the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting (ADMM) and China established the Xiangshan Forum,Footnote 93 both in 2006. The Raisina Dialogue, which has a South Asian emphasis, was established in 2016.Footnote 94 Informal processes have also proliferated, such as the Track II Network of ASEAN Defense and Security Institutions (NADI), which is a think tank network similar to ASEAN-ISIS and CSCAP and closely aligned with the ADMM.Footnote 95 In sum, after decades of catching up to the complex constellation of security diplomacy in Europe, ‘Asia's track two dialogues are numerous and diverse. There is no precise count, but estimates from one reputable source suggest that hundreds of such meetings take place every year (Dialogue and Research Monitor, 2007).’Footnote 96 Despite the present wealth of both formal and informal security dialogues across Asia, the SLD still retains its premier place on the year's agenda. In fact, it often overshadows many state-sponsored and formal dialogues, many of which have been criticised as ineffective and inefficient.

The Shangri-La Dialogue

The International Institute for Strategic Studies hosted the first Shangri-La Dialogue (SLD) in Singapore in 2002.Footnote 97 Since then, the Dialogue ‘has consistently managed to generate favorable opinion among regional elite’Footnote 98 and it is known for having a ‘considerable policy impact’.Footnote 99 For example, spurred by the Sichuan earthquake and Cyclone Nargis in 2008, it was at the Dialogue that attending ministers agreed to a set of principles guiding responses to humanitarian disasters.Footnote 100 The Dialogue was also the location of the announcement for the ‘Eyes in the Sky initiative’, a joint effort between Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia to combat piracy in the Malacca Straits using air patrols. The success of the Dialogue has also had an impact in that it served as evidence that a regional security dialogue was viable and ‘it is reasonable to suppose that the Shangri-La process helped to erode the hesitations within ASEAN about allowing defence ministers to establish their own forum’.Footnote 101 As noted by the then-US Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel, ‘there's no other event, no other venue like it’.Footnote 102

The Shangri-La Dialogue as a discursive space

The SLD is a ‘unique meeting of ministers and delegates from over 50 countries’. It facilitates ‘easy communication and fruitful contact among the region's most important defence and security policymakers. Each year's agenda is intentionally wide-ranging, reflecting the many defence and security challenges facing a large and diverse region.’Footnote 103

The SLD was modelled on the MSC, and the Director General of the IISS, which organises the Shangri-La Dialogue, has been a regular attender of the Munich Security Conference.Footnote 104 Much like the MSC, the SLD has adapted itself to the changing dynamics of the region and has endeavoured to keep the three components of high-quality discourse we identified earlier in this article in balance, albeit in different ways.

Whereas the MSC explicitly portrays itself as an ‘informal’ conference with ‘formal’ attendees, the Executive Director of IISS-Asia stated that he believes the dialogue to be T1, despite the fact that the agenda is controlled by the IISS (ID7). Even so, we maintain that the SLD more accurately fits the description of T1.5 given that it is not organised by a sovereign state but rather a non-governmental entity. Regardless of the label applied, the SLD has placed itself in the nebulous political space between formal and informal governing structures. It is one of the very few which have overtly sought to occupy the space that straddles the boundaries between policymakers and experts, and political power and innovative ideas.

Levels of formality

The SLD enjoys many of the advantages of being an informal structure (control of its own agenda, lack of public scrutiny, no predetermined outcomes), while also benefiting from having high-ranking and influential policymakers attending in their formal capacities.Footnote 105 In fact, the SLD uses this autonomy as a draw for high-ranking officials (ID7).

Like the MSC, its format and participants are fungible and it does not seek to produce an agreed upon communiqué.Footnote 106 This flexibility, previously considered evidence of weakness in other dialogues, is now seen as an indication of diplomatic and institutional maturity.Footnote 107 Regardless of this gradual change in perception, the SLD remains unique. Security expert Desmond Ball noted that ‘it will be a while before the ADMM-Plus will be prepared to tackle the inter-state issues that form the main themes of the SLD. The ADMM-Plus does not provide an opportunity for publicly airing, let alone debating, policy positions.’Footnote 108

Due to its diverse levels of formality, the SLD fosters communicative discourse as it ‘provides an important platform from which the national stakeholders in Asia-Pacific security may rehearse and clarify their defence politics’. It also creates space for coordinative discourse as it offers ‘significant opportunities for more detailed, off-the-record discussions of key security concerns’.Footnote 109 This unique combination of discursive spaces bridges the gap between formal policy and the processes of politics and policymaking in a region where such forums are in short supply.

The levels of formality vary across and within the three-day Dialogue. The most formal aspect is the plenary sessions. These sessions are largely composed of communicative discourse, similar to other regional dialogues, except they differ in that ‘any participant in the dialogue (including journalists and academics) is able to stand up and ask a question without giving prior notice’.Footnote 110 These sessions are considered ‘on the record’ and many important policy announcements, as well as praises and criticisms of other attending countries, have been made at the SLD. Less formal, and private in nature, are special sessions. These are issue specific gatherings hosted by the IISS. While they are open to all attendees, they are considered off-the-record, and speaking slots are largely assigned to governmental representatives. These sessions provide the opportunity for state representatives to both clarify their nation's stance on policy issues (communicative discourse) as well as discuss these issues with those in attendance (coordinative discourse).

The most informal, and the main draw of the SLD, are the opportunities for defence ministers to meet bi- or trilaterally (ID7).Footnote 111 Facilitated by the IISS, these are organised by the respective states and can either be conducted privately or publicly. Within these meetings, defence officials are at liberty to be frank should they choose to be. It is common for defence officials to schedule anywhere from 15–20 such meetings throughout the Dialogue and as David Capie and Brendan Taylor noted, ‘interviews suggest that officials undoubtedly put the greatest value on the short bilateral interactions which occur on the sidelines of the conference’.Footnote 112 By far, these meetings have the most coordinative potential and are one of the few opportunities per year that defence officials get to meet privately with their counterparts from other countries.

Types of discourse

There is diversity in both the types and levels of ideas presented at the SLD. A major contributor to this is the fact that the SLD is not organised by a national government and enjoys multiple sources of funding. This includes governmental funding, particularly from the Singaporean, Japanese, and Australian governments; private grants from companies such as BAE Systems and Boeing, and foundations such as the MacArthur Foundation.Footnote 113 While this funding may be in return for access to security policymakers, the SLD has been able to diversify its funding sources, and the comparative presence and influence of the military-industrial complex has diminished. The attempt was to enhance the quality of discourse by facilitating ‘the participation of greater numbers of non-official participants, to maintain the quality of non-official participants, and to encourage the participation of more non-official representatives from smaller states and younger participants’.Footnote 114 While the SLD claims to host a diversity of actors, it is not an ‘open’ forum. The SLD has striven to keep the dialogue from becoming ‘an old boy's club’ by encouraging civil society participation, and the inclusion of young leaders so that speakers get challenging and astute questions they would not get in a static meeting (ID7). The Dialogue recently started the South Asian Young Leaders’ Program to incorporate more youth in discussion but has had less overt success in including NGOs.Footnote 115 The organisers have also made efforts to ensure that the content of the ideas (via the agenda and selective inclusion of certain civil society participants) is kept dynamic and ‘not prone to stagnation, as can sometimes become the case in the regional dialogue business’.Footnote 116 As Jina Lim recently noted, this is more likely to happen ‘on the sidelines, … involving invited members of the Track 2 community [non-governmental and unofficial, for example, academics, think tanks, media, etc.], a particular niche of the SLD.’ Indeed, ‘each part of the Dialogue has its purpose – public sessions enable signalling of commitment, announcement of policies, … and questioning – even “interrogation” of officials by non-government participants’.Footnote 117

Access to governing authority

While other forums have struggled with waning or inconsistent attendance or high-level support, the Shangri-La Dialogue reliably attracts the highest levels of defence officials to its yearly meeting. At present, the Dialogue is most regularly attended by senior military officers and defence officials, often at the ministerial level. The attendance of such high-level officials is self-reinforcing, as countries that are interested in engaging with regional discourses will send high-level officials if they know that their discourses will be received by other high-level officials.

For instance, the attendance of a ministerial-level attendee, like the then-Chinese defence minister in 2011, gave the Dialogue a certain level of legitimacy, in terms of potential access to governing authority. However, after a particularly confrontational exchange China chose to express its displeasure by then sending a member of the PLA's Academy of Military Science to the Dialogue instead of an official from the Ministry of National Defense from 2016 to 2018. The downgrading of its attendees was an attempt to indirectly censure the Dialogue by removing high-level participants, but rather proved the point that the quality of dialogue was such that it made the Chinese government uncomfortable with the type and the quality of the discourse that takes place at the SLD.Footnote 118 China had to cope with the fact of having ‘little influence over the agenda’, which means that it is often faced with issues it does not wish to discuss and being broached in a manner it is uncomfortable with in an ‘open, multilateral setting’.Footnote 119

Conclusions

This article serves as a preliminarily attempt to unravel the complex factors rendering specific Track 1.5 security dialogues more relevant and enduring than other types of regional security dialogues. It also offers a concrete clarification about the three multitrack forms of diplomacy that we associate with different types and functions of discourse.

Drawing upon existing discourse approaches we have clarified and broadened upon the concept of the quality of discursive space and identified this as an important feature determining the success of regional security processes. We have argued that for a dialogue to have high quality discursive space it must have a balance of at least three identified important characteristics: the level of formality/informality; the types of discourse used, and access to governing authority. In other words, in this article we have found a combination of factors to be a promising explanatory key to improve our understanding of the role of Track 1.5 diplomacy forums.

The empirical analysis carried out in the time frame of a decade, from 2009 to 2019, has applied these factors to the two selected cases studies, the MSC in Europe and the SLD in Asia, after carefully considering the respective emerging competitors and other similar forums. Our findings from the empirical analysis provide an important contribution to the literature on discourse, by developing the concept of discursive space and highlighting the factors that are relevant for discursive quality in the context of multitrack diplomacy and security practice.

When viewed through our proposed analytical framework, both the MSC and the SLD appear to have found their own balance among the mentioned factors: they can boast unique ‘hierarchies of formality’ that allow for a wealth of communicative and coordinative ideational exchanges, and enjoy robust attendance by high-level policymakers, mitigated by representation by other ideational and policy stakeholders. This means that new or innovative ideas can potentially be exchanged in the discursive spaces created within these dialogues. Alongside, relationships between individuals representing state and non-state actors can be further developed and brought home to each single institution.

Furthermore, the enduring relevance of the MSC and of the SLD has not gone unnoticed and there are clear indications that other forums, both state and non-state alike, are actively attempting to recreate their special discursive environments by copying their format. For instance, the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting has adopted many of the characteristics of the SLD (including bilateral meetings, private sessions, incorporating experts, and holding seminars). The ADMM and ADMM + processes are not the only competition to the SLD. Indeed, China arguably established the Xiangshan Forum as a direct competitor to the SLD, with the aim of emphasising the communicative discourses of China. Despite having a decade to mature, this forum has not achieved traction equal to the SLD because the Chinese-controlled agenda has led participants to question its impartiality and thus its utility. In other words, state control over dialogues may create a discursive space with some levels of informality and access to governmental authority, but that is hostile towards ideational diversity and coordinative discourse.

In Europe, potential competition to the MSC comes from a varied array of conferences and dialogues. As of yet, there is no singular security dialogue that is able to compete with the MSC's longevity and ability to be more inclusive over time. In effect, the MSC appears enduring and stable in its capacity to remain ‘The Event’ of security practitioners and policymakers in Europe. As a matter of fact, given the difficulty to fund any other similar project in the long term it is hard to argue that the MSC is at risk of being replaced by other forums. Above all, the MSC has certainly influenced the way in which Track 1.5 security diplomacy is being exerted, and newcomers like the Rome MED Dialogues are adopting formats that are similar to those of the MSC. The attempts by other dialogues, while not definitive, are an additional indication that the importance of a balance between the three identified components is applicable across different contexts.

Ultimately, shortcomings in studies like ours are to be found in the ‘persistent inability to adequately explain the sources of profound transformations in powerful narratives and in terms of the challenges associated with the study of non-material and more diffuse dimensions and effects of power that the concept of discourse entails'.Footnote 120 More contingent limits of this research pertain to the limited access independent researchers external to these security communities may encounter when approaching and attempting to interview participants to these dialogues. We are aware that the limits of generalisability of this study due to the fact that the empirical evidence may be biased because behind-closed-door activities are rarely reported and certain empirical evidence does not appear in interviews.

This article, we hope, lays a solid foundation for additional research in this area. The provided case studies were intended to serve as exploratory examples and, we believe, are only initial forays into the future possible research. Future avenues for research might include applying the developed theoretical framework to other dialogues and contexts, as a way to enhance the understanding of the role of non-state agents in regional security governance and of the new forms of diplomacy.

Acknowledgements

Our names are listed in alphabetical order. The authors are extremely grateful for the useful comments both from the anonymous reviewers and the editors of the journal. We also want to thank all the professionals interviewed in Europe and Asia, who we believe are part of an incredible and sometimes invisible community of knowledge.

Anna Longhini is a researcher at Scuola Normale Superiore (SNS) in Florence, where she also earned her PhD in Political Science with research on foreign policy think tanks in Europe. Her previous work was published by the Central European Journal of Public Policy and the International Journal: Canada's Journal of Global Policy Analysis. Author's email: [email protected]

Erin Zimmerman received her PhD from the University of Adelaide, Australia in 2013. She is an Associate at the German Institute of Global and Area Studies in Hamburg, Germany. Her current research focuses on non-state actors as governance entrepreneurs, emerging governance structures, and non-traditional security. Her most recent book, Governance Entrepreneurs: Think Tanks and Non-Traditional Security in Southeast Asia, was published by Palgrave MacMillan in 2016. Author's email: [email protected]