Introduction

The rise of the far right in Brazil, under the government of Jair M. Bolsonaro (2019–22), represented a clear-cut break with the country’s long-standing commitment and contribution to the International Liberal Order (ILO). Bolsonaro’s foreign policy committed not only to an ideological alignment with kindred far-right and authoritarian governments around the world but also produced several withdrawals in terms of Brazil’s participation in multilateral mechanisms and peace processes both at the global and regional levels.Footnote 1 Brazil’s contestation of ILO involved a combination of conspiracy theories about globalism, home-grown anti-communist sentiments, and religious nationalism.Footnote 2 For the first time in the democratic period, a religious agenda stemming from conservative Catholic and Evangelical groups was channelled into foreign policy decision-making, which resulted in the government frequently chastising the human rights agenda.Footnote 3 This was in stark contrast with the previous cycle of centre-left governments (2003–16), which were internationally hailed for Brazil’s leadership in liberal peacebuilding projects, especially in the case of the United Nations’ (UN’s) Stabilisation Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) (2004–17).

This article seeks to analyse the relationship between foreign and domestic peace processes and far-right forces in Brazil. However, rather than focusing on the ways in which Bolsonaro’s government aligned with and contributed to counter-peace dynamics and alliances, we shift attention to a less intuitive relationship: did Brazil’s participation in recent peace operations contribute to the emergence and mainstreaming of the far right in the country? Underpinning this framing of the problem is the recognition by critical peace scholars that the International Peace Architecture (IPA) has been implicated in the rise of counter-peace due to its ‘rejection of the expanded political claims of the Global South’ with a narrow focus on basic human rights and limited democratisation.Footnote 4 Other studies have also suggested that liberal peacebuilding can contribute to the consolidation of authoritarianism in host countries,Footnote 5 and that while security sector reforms may strengthen the trust and power of state security forces, this can be divorced from the parallel development of accountability mechanisms.Footnote 6 While most of this scholarship focuses on conflict-ridden, underdeveloped countries, we follow a small but growing body of scholarship that argues that liberal peacebuilding can also enable authoritarianism and de-democratisation in the deployer country.Footnote 7

Brazil offers an interesting case in point, as the main elements of the far-right political agenda, namely militarism, Christian moralism, and neoliberalism,Footnote 8 had been previously bundled as orienting principles of pacification efforts at home and abroad. This was the case in pacification operations led by the military in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas from 2008–14, and concurrently in the country’s leadership in Port-au-Prince under MINUSTAH. We follow the suggestion of some scholars who claim that the Port-Au-Prince-Rio connection prefigured BolsonarismoFootnote 9 and seek to contribute to better understanding how to conceptualise this relationship, which remains under-explored in the literature.

We argue that Brazil’s engagement in the pacification of Port-au-Prince and Rio de Janeiro contributed to the process of strengthening the far right in Brazil in two important ways. The first was through a military (re-)capture of politics, as a large portion of the high-ranking military elite that participated in both interventions enabled the military to take a more prominent role in Brazil’s domestic politics, which ultimately weighed in on the far-right turn. Second, Port-au-Prince and Rio de Janeiro became crucial sites for experimentation with a range of policy ideas that Bolsonaro later capitalised on. On the one hand, the stringent and repressive approach utilised by the military in these operations set the backdrop for the advancement of punitive reforms within the domestic security apparatus – actions relied on traditional role conceptions and pre-existing operational experiences by the Brazilian military.Footnote 10 This was justified based on the need for efficiency and legal support in combating crime. On the other hand, the military had also embraced a range of sensibilities underlying the local turn in peace operations – such as human rights and community policing – and reappropriated them to enhance counter-insurgency tactics. The most striking manifestation of this was the mobilisation of a constellation of religious actors and morals to support and justify the military occupation in Rio de Janeiro. Via the military chaplaincy, Evangelical conservative ideology was activated as part of a wider project of order-building and violence regulation in marginalised urban areas in Brazil – a strategy that echoed Bolsonaro’s subsequent instrumentalisation of Evangelicalism for both electoral gains and policy ideals.Footnote 11

The first section of this article briefly analyses the rise of counter-peace dynamics in Brazil, focusing on the dismantling of pro-IPA initiatives after the end of the Workers’ Party governments. The second section analyses the context and dynamics of the Brazilian military’s involvement in peacekeeping operations in Port-au-Prince and Rio de Janeiro, outlining the strategies deployed in the field of operations and their mutual points of connection. The third section unpacks how the military mobilised religious actors and networks via the military chaplaincy to advance counter-insurgent actions in Rio de Janeiro. The last section explores how the military was politically empowered in the aftermath of the militarised interventions in Port-au-Prince and Rio de Janeiro, becoming a key actor in the authoritarian turn in security policies as well as a co-protagonist in the mainstreaming of the far right.

For this study, we rely on a combination of literature review, document analysis, and interviews conducted by Rodrigo during fieldwork for his doctoral research. The literature review is based on scholarship around Brazil’s leadership in MINUSTAH, the armed intervention in Rio de Janeiro’s urban favelas, and the role played by Evangelical actors in the field of security in recent years. Regarding document analysis, we focus on the Brazilian army’s religious doctrine in terrestrial operations, published in 2018, which crystallised years of experience using the military chaplaincy as a counter-insurgency asset in urban warfare operations. Finally, we rely on interviews with two insiders with extensive experience in Rio’s pacification operations: one is a former Evangelical military chaplain who worked for the army’s military-religious project during the occupation, and the other is a researcher who worked many years for NGOs in the occupied territories and conducted fieldwork research with the high commands of the army. Both names have been pseudonymised.

The far right and the rise of counter-peace dynamics in Brazil

Bolsonarismo was part and parcel of an ongoing backlash against ILO with the global rise of the far right and growing geopolitical protagonism of illiberal regimes on the global stage.Footnote 12 Within IPA scholarship, this backlash has been identified as the emergence of counter-peace, defined as ‘formal and informal structures and processes that resist and reshape the political order sought by peace processes’.Footnote 13 By exploiting the weaknesses and unintended consequences of liberal-peacebuilding, counter-peace forces have mobilised nationalism and geopolitics not only to counter norms and practices associated with IPA but also to pose a more systemic challenge to the international system itself.Footnote 14

Since Luiz da Silva’s (or Lula’s) first terms (2003–10), efforts to contribute to the IPA multiplied as Brazil took a much more proactive approach in multilateral forums, engaging in coalition-building with other rising economies across the Global South to reform global governance structures, especially the UN Security Council.Footnote 15 Examples of this were high-level attempts at conflict mediation around Iran’s nuclear deal in 2010; increased budget for demand-driven development cooperation projects with post-conflict countries such as Angola, Zimbabwe, Guinea-Bissau, and Timor-Leste; greater participation in peacekeeping operations, the country’s leadership of the military command of MINUSTAH from 2004 to 2017; and, on the home front, the expansion of its own pacification operations in Rio de Janeiro’s marginalised urban areas, with the Unidades de Polícia Pacificadoras (Pacifying Police Units [UPPs]), created ahead of the World Cup (2014) and the Olympics (2016).Footnote 16

Underpinning Lula’s rationale for deploying the military in peace operations was a belief that it could strengthen civilian control over the armed forces, what the literature has called the ‘diversionary peace hypothesis’, the assumption that peacekeeping missions help professionalise the military and steer them away from politics.Footnote 17 However, efforts to contribute to IPA have developed in step with the maintenance and, to a certain extent, greater institutional autonomy of the armed forces. Despite mild institutional reforms, such as the strengthening of the Ministry of Defence with a civilian character, the military ultimately succeeded in reversing key decisions by civilian authorities.Footnote 18 Significant shifts in Brazil’s foreign policy started being felt already during Michel Temer’s interim office (2016–18), following the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff, Lula’s successor, in 2016. The more reformist, middle-power ambitions on the international stage were sidelined in favour of geopolitical alignment with the United States and the adoption of a neoliberal economic agenda.Footnote 19 Under foreign minister José Serra, humanitarian assistance programmes were deprioritised,Footnote 20 and there were pushes to change Brazil’s position regarding the Israeli–Palestinian conflict at the UN in favour of Israel, although this was met with domestic resistance.Footnote 21 On the domestic agenda, public security policies also went through a markedly authoritarian turn, especially with the Federal Intervention in Rio de Janeiro between February and December 2018, which placed the security apparatus of the state government under military administration, stripping the democratic and humanitarian facade of previous pacification efforts.Footnote 22 On this occasion, Torquato Jardim, then minister of justice, equated the military intervention in Rio’s urban slums as ‘asymmetric warfare’, wherein ‘anyone can be the enemy, there is no uniform, you don’t know what the arms are. You are always ready against everything and everybody.’Footnote 23 The Federal Intervention was preceded by a significant change in Brazilian legislation in October 2017, which posited that military personnel who committed crimes during peace operations or in domestic operations would be prosecuted by the military justice system, rather than in civilian courts.Footnote 24

Bolsonaro’s government radicalised this trajectory. Brazilian diplomacy has historically played a relevant role in peacebuilding debates and practices, especially in the areas of development cooperation, international conflict mediation, and humanitarian assistance.Footnote 25 However, Bolsonaro’s government deepened relations with the Israeli far right, promising to move the Brazilian embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Although this was not carried out, his government opened a commercial office in Jerusalem after an official diplomatic visit in March 2019.Footnote 26 In the same month, the country opposed a series of resolutions at the UN’s Human Rights Council condemning violations against Palestinians perpetrated by Israel.Footnote 27 At the end of 2020, the government decided to phase out its participation in the UN’s Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), where Brazil commanded its maritime force. This resulted in the lowest participation in peacekeeping operations in Brazil’s history.Footnote 28 Ernesto Araújo, foreign minister between 2019 and 2021, was ideologically enthusiastic about this isolationist foreign policy: ‘if this makes us an international pariah, then let us be this pariah’.Footnote 29

Rather than deploying military troops in peace operations abroad, however, the military was politically deployed on the home front. Bolsonaro’s government was the most militarised since the end of the civilian-military dictatorship (1964–85). In 2018, members of the armed forces held 2,765 posts in the federal government. Under Bolsonaro, this number rose to 6,175 in 2020, with the military occupying key areas in government.Footnote 30

However, the political reactivation of the military under Bolsonaro’s government was a testament not only to vestiges of the military regime during the democratic period, but of a much older tradition of militarisation of political life that dates to the colonial period. Historically, Brazil’s development as a dependent capitalist country has been inseparable from the construction of a centralising, militarised state anchored in structures of war, enslavement, and violence directed against marginalised populations, with the imperative to protect and reproduce a racialised, hierarchical, and authoritarian social order.Footnote 31 In the transition from Empire to Republic, the military constituted itself as a ‘moderating force’, periodically intervening in politics to uphold the dominant order when it was challenged either by revolts or attempts to democratise institutions and incorporate the popular sectors through redistributive social policies.Footnote 32 Militarism reached its highest expression during the military dictatorship, in which a far-right regime was sustained via a National Security Doctrine that utilised repression, torture, and political terror to neutralise working-class mobilisation.Footnote 33

With the end of the military dictatorship, security policies saw a shift from discourse and practices based on fighting political subversives to targeting urban criminality and narcotics through an almost-exclusive attention to militarised police models.Footnote 34 However, the National Security Doctrine was re-adapted to policing, with techniques of political repression being transferred to the patrolling of everyday criminality by the military police.Footnote 35 Not only was the military not held accountable for human rights violations in the transitional period,Footnote 36 but military officials have also since become increasingly involved with public security policies at the domestic level.Footnote 37 For instance, many generals have occupied key positions in the security secretariat of different state governments, and security actors continued to participate in electoral politics.Footnote 38 Further, the 1988 Constitution granted that the military can be internally deployed under a legal instrument named the Garantia da Lei e da Ordem (the Law and Order Guarantee [GLO]), which can be summoned by the President of the Republic in cases of depletion of security forces, severe disturbances of order, or for the security of large events. In GLO operations, the armed forces are trusted with police powers for a provisional period to perform ‘actions of preventive and repressive nature necessary to assure the outcome of operations’.Footnote 39 In sum, the boundaries of domestic safety and national security/defence have been continuously blurred since re-democratisation, making it difficult to distinguish, for instance, the roles of policing from militarism.Footnote 40

Bolsonaro, a former captain in the army who throughout his political career echoed a militarist discourse, was able to capitalise on the long-term legacies of militarism, using it as the backbone of his far-right platform. This platform was also shaped, however, by more recent developments. We argue that the far right was strengthened by, and relatively dependent on, the experience of the Brazilian military in peacekeeping operations both in MINUSTAH and in Rio de Janeiro under the UPPs project, both of which took place under the progressive governments of the Workers’ Party and under a liberal ticket of peacebuilding efforts.

The Port-au-Prince–Rio connection

Brazil’s engagement in MINUSTAH (2004–17) was a clear turning point in its history of contributions to peacekeeping. It was Brazil’s largest mission by number of troops since World War II (more than 30,000), with a continuous engagement that lasted 13 years. Brazilian generals were also the military leaders of the mission, occupying the role of Force Commanders. As a Chapter VII mission, MINUSTAH was authorised to use force to fulfil its mandate. This was grounded on the ‘robust turn’ in UN peacekeeping since the late 1990s, contrasting with traditional peacekeeping missions that were based on the principles of limited use of force in cases of self-defence, on impartiality, and on consensus.Footnote 41 In the robust turn, Chapter VII missions have become more commonplace, not only authorising the use of force but deliberately taking sides in conflicts.Footnote 42 In the case of Haiti, as the country was not in civil war, the Security Council considered armed gangs as ‘mission spoilers’, some with a relatively high degree of legitimacy in local communities. Thus, in MINUSTAH military operations were marked by armed intervention in working-class neighbourhoods, the use of snipers, the deployment of special forces units, and the use of informers among the local population.Footnote 43

Although initially reluctant to use force, Force Commander General Augusto Heleno yielded to pressures from Haiti’s transitional government, foreign ambassadors from the United States, France, and Canada, and the business community in Port-au-Prince. He introduced joint military-police interventions in impoverished urban neighbourhoods like Cité Soleil and Bel Air, targeting armed groups labelled as ‘gangs’.Footnote 44 Most of these robust operations were concentrated in the period between 2004 and 2007, and they were usually led by a taskforce comprising foreign military and police personnel as well as members of the National Police of Haiti. On 6 July 2005, for example, in Haiti Heleno commanded the Iron Fist Operation in Cité Soleil, a densely populated area with around 350,000 residents at the time. Reports by human rights organisations highlight the disproportionate use of force by the heavily armed peacekeepers, who fired 22,700 rounds of ammunition and used 78 grenades in a single operation.Footnote 45 According to Wils and McLaughlin,

MINUSTAH closed all exits from and entrances into Cité Soleil, and prevented anyone, including the Red Cross, from entering for between 24 and 48 hours after each UN operation. This prevented gang members from leaving but it also meant that people could not escape the heavy onslaught of fire. Dr. Armstrong Charlot … spoke of his extreme shock at the number of young children who were so badly injured they could not be saved … US Ambassador to Haiti, James Foley, acknowledged that on the night of 6 July 2005 UN forces ‘expended over 20,000 rounds of ammunition’.Footnote 46

MINUSTAH’s ‘robust’ operations followed a military strategy known as ‘stronghold’ (or ponto forte in Portuguese). The objective was to conquer strategic areas and facilities in the neighbourhoods, establish a permanent or temporary base, centralise regular patrols, maintain a constant presence, and extend the state’s control over targeted territories, thereby removing or diminishing the influence of armed gangs. During those missions, it was common for the taskforce to employ resources such as armoured personnel carriers and helicopters.Footnote 47 Stronghold operations were followed by the implementation of so-called Ações Cívico-Sociais (Social-Civic Actions programmes [ACISOs]), a dictatorship-era instrument widely utilised by the Brazilian military in domestic urban operations.Footnote 48 With the aid of non-state actors, the military provided free social services to locals such as medical treatment, football tournaments, and engineering installations. International NGOs, such as the Brazilian Viva Rio, were key partners in the implementation of these initiatives, acting as consultants to the mission and engaging in reconciliation measures within affected communities.Footnote 49

With ACISOs, the Brazilian had the opportunity to experiment with more ‘soft approaches’ to security that were ‘attuned to global sensitivities regarding human rights, democracy, and the rule of law’.Footnote 50 However, they also represented an important tactical element for the military success of operations, which was to obtain legitimation from the population.Footnote 51 These innovations were also related to a doctrinal change in peace operations, in which intelligence gathering became a key aspect of the mission. The UN Security Council established a hub for intelligence collection and analysis, resorting to a network of paid informants to help identify gang members (viewed as ‘peace spoilers’) to arrest or kill.Footnote 52 General Heleno claimed that ACISOs were important to gain locals’ ‘hearts and minds’, resulting in Haitians ‘going overnight [to the base] to pass information about bandits’.Footnote 53

At the same time, in Rio de Janeiro’s working-class neighbourhoods known as favelas, the stronghold strategy was also being mobilised by the Brazilian military in the implementation of the public security program called Unidades de Polícia Pacificadoras (Pacifying Police Units [UPPs]). ‘Pacification’ has a long tradition in Brazil’s political and military history since colonialism, invariably signifying the utilisation of state violence to conquer, subjugate, and control territories and marginalised populations.Footnote 54 Pacification discourses are also routinely deployed as a key concept in the military’s projection of an imagined homogeneous national identity.Footnote 55

UPPs began shortly after the 2007 announcement that Brazil would host the World Cup in 2014 and the Olympics in 2016. Rio had been inserted in the global circuit of sport mega-events (previously, the Pan-American Olympics in 2007 and the Military Games in 2010), which transformed its security governance into a global issue that required engagement from a range of state and non-state actors. The idea of Rio as a ‘global competitive city’, which would place it on a governance network of public policy ‘best practices’ and signal attractiveness to foreign investors, was a key branding component of the UPPs project. Most of UPP units were localised in the southern region of the city, surrounding the famous Maracanã stadium and middle-class neighbourhoods.Footnote 56 In total, 38 UPPs were implemented between 2008 and 2014, covering 196 favelas with around 700,000 residents.

The UPPs represented a strategy to reinstate state control over favelas dominated by drug gangs through military force, and later to establish permanent community policing units, which would include social programmes. The latter aimed to integrate favela spaces and residents into the wider city in terms of services, infrastructure, investments, and rights.Footnote 57 Although the UPPs were a welcomed project by locals at first, perceptions soon shifted as it became clear that the ‘warfare’ logic was much more present than the ‘social’ one. Social movements criticised the rationale behind UPPs, which prioritised the ‘conquering’ of territories, the ‘neutralisation’ of real or suspected enemies, and the establishing of a ‘tutelar’ form of authority.Footnote 58 As a colonel who commanded the Pacifying Force in the Complexo do Alemão, Vladimir Ferreira, claimed about the operation:

The greatest difficulty we have here is in acting against Brazilians. It’s different to other typical military operations where we have a defined physical enemy in uniform. In urban confrontation, we cannot see the enemy on the other side. The drug dealer, the thief and the suspects are among the people.Footnote 59

Similar to the Haitian experience, it was a counter-insurgency perspective that oriented UPPs’ ‘soft’ approach to security once the military occupation had taken place. The idea was that residents could supply security forces with privileged information about ongoing unrest, social mobilisation against police presence, and intelligence about suspected criminals.Footnote 60 Thus, pacification in Rio and in Haiti were much more about the police becoming the regulating force of social order rather than tackling structural problems of inequality, poverty, and lack of public services.Footnote 61

The UPPs and MINUSTAH operations were not isolated from one another. Officials have long recognised the points of intersection between them. General Heleno, for instance, argued that social projects developed in Port-au-Prince ‘helped a lot in the pacification and became the embryo of the Pacification Police Units in Rio de Janeiro’.Footnote 62 By the end of 2010, around 60 per cent of military troops deployed in the pacification of the Maré favela in Rio had participated in MINUSTAH.Footnote 63 According to Müller and Steinke:

Brazil’s MINUSTAH experience allowed for a fine-tuning of previous pacification experiences and their ‘upgrading’ to globally dominant counterinsurgency standards, which, in turn, influenced pacification-related military doctrinal revisions processes and intervention practices at home.Footnote 64

The Port-au-Prince–Rio connection has also been regarded as synergically co-constituted in both Brazil and Haiti, with elements of reciprocal learning between the two contexts.Footnote 65 The techniques of repression and social control, developed in contexts of violent actions and local resistances, have been imported and exported in a ‘boomerang effect’ that crossed international borders.Footnote 66

Perfecting counter-insurgency: The mobilisation of religious actors

One key element that the Brazilian military sought to improve at home based on its experience in MINUSTAH was a strategy of obtaining legitimacy for the intervention among the affected population. According to Oosterbaan and Machado, Haiti forced the military to learn that ‘pacifying practices demand more than enemy identification, weapons and brute force. One also needs symbolic, cultural and political devices to secure and control occupied territories.’Footnote 67 In Rio, this was sought through the mobilisation of conservative Christian ideology, especially Evangelical Pentecostalism. In this process, religion was instrumentalised to bolster legitimacy for militarised forms of intervention and utilised as a blueprint for order-building in urban peripheries.

The relationship between religious actors and security governance is not a new one in Brazil. Since re-democratisation, religious actors have been engaged as mediators, alongside human rights activists and NGOs, in tackling issues of urban violence and crime.Footnote 68 Evangelicals – which in Brazil comprise both mainline Protestants and Pentecostalist traditions – have been at the forefront of this trend, incorporating the security agenda into their discourse and practice both from a top-down and bottom-up approach.Footnote 69 In the case of the former, Evangelical political activism has become entwined with law-and-order, militaristic policies formed in alliances with so-called bullet caucuses in legislative institutions such as city councils, state assemblies, and the National Congress.Footnote 70 In Congress, for instance, the articulation between the Evangelical Parliamentary Front and the Public Security Parliamentary Front reached its peak in the 2015–18 legislature, when it shifted from a survival strategy of fringe political groups to become an influential political force during President Rousseff’s impeachment proceedings. From the 376 votes in favour of her ousting, 101 votes came from MPs that participated in both Fronts.Footnote 71 Additionally, Lacerda’s study found that there was ‘association between being a police or military officer and participating in the evangelical caucus’, and ‘in being protagonist in public security-related commissions and being a member of the Evangelical Front’.Footnote 72

In the case of the latter, the rapid spread of Pentecostalism on the outskirts of urban areas – affected by high rates of violence exercised by both non-state and state actors, and aggravated by neoliberal adjustments – has led to new forms of violence regulation and solidarity networks. These networks navigate the porous borders between licit and illicit activities, and state and non-state actors.Footnote 73 The logic of violence produced on the urban margins, and compounded by a Pentecostalist theology of spiritual warfare, was crucial to the rise of Bolsonarismo as a mass movement.Footnote 74

Machado notes that Evangelicals have developed a ‘very specific repertoire for tackling violence’, ranging from ‘devotional practices focused on the “spiritual battle” against crime, to an intense evangelization of imprisoned criminals, or direct negotiations with criminal gang leaders in order to convince them to release “bandits” condemned to death by “drug gang courts”’.Footnote 75 A noticeable element of these interventions is militarisation: scholars have observed the emergence of Evangelical drug cartels and militias.Footnote 76 Evangelical police culture,Footnote 77 and Evangelical churches and pastors increasingly making use of militarised vocabulary, uniform, and military-style ‘prayer patrols’.Footnote 78

Such religious–military entwinement was also present during the UPP project in Rio de Janeiro. In many UPPs, the military police engaged with religious actors as a strategy of winning the hearts and minds of local residents. Examples ranged from partnering with Evangelical churches controlling so-called therapeutic communities for the treatment of drug addictsFootnote 79 and the organisation of gospel concerts promoted by Rio’s Special Operations Battalion,Footnote 80 to the use of military police chaplains to build trust relations with local residents.Footnote 81 Salem and Bertelsen’s ethnographic work also noted that UPP police officers routinely manifested a form of police moralism in their relationship with locals, anchored in a Pentecostal morality and racialised tropes that cast locals as ‘easily corruptible and morally inferior people in need of salvation’.Footnote 82

However, this post-secular pacification logicFootnote 83 was much more pervasive under the army’s military occupation of three large favela complexes, Alemão, Penha, and Maré. These occupations were staged as preliminary phases before the implementation of UPPs. The occupation in the Alemão and Penha occurred between 2010 and 2014, with a contingent of 1,800 soldiers, and in Maré between 2014 and 2016, with a contingent of 2,400 soldiers.Footnote 84 These interventions were tellingly titled Operation Archangel (Alemão and Penha) and St Francis (Maré) and were designed by the Rio de Janeiro state government to push criminal factions away from rich neighbourhoods adjacent to these territories. This was to secure the flow of business investments and tourists ahead of the World Cup and Olympics.

As in Haiti, the prolonged period of military occupation in Operation Archangel had forced the military to develop strategies of approximation with the local population. Initially this was done via neighbourhood associations and local NGOs, but cultivating these networks proved difficult as the military grew suspicious of their contact and interaction with criminal factions.Footnote 85 In the military’s interpretation, the difficulty and ambiguity in distinguishing friends from enemies in this urban warfare setting, together with growing public criticism towards the occupation, indicated the need to establish partnerships with groups that shared similar values. Local religious actors were thus activated as trustful partners who could be mobilised to mediate the increasingly tense relationship with residents.Footnote 86 According to Jonas (fictional name), a former Evangelical military chaplain who served during the occupation,

The military had this view that the rest of the population was contaminated, that it bears the mark of impurity, especially among neighbourhood associations. And other things were also reason for mistrust, you know? They [the military] would accept dialogue, but always with suspicion. ‘People from hip-hop and from funk [a popular musical genre], who are they?’ ‘These people have contact with and are co-opted by drug trafficking, I don’t trust them.’ ‘Pastors and priests are more trustworthy.’

The establishment of networks with religious actors was assigned to the Department of Religious Assistance of the East Military Command of Rio de Janeiro. Military chaplains were deployed on two simultaneous fronts, internal and external. Internally, they were used as a tool of ideological coherence to boost troop morale. This follows from traditional attributions of the military chaplaincy, which according to a federal law, ‘aims to provide religious and spiritual assistance to the military, civilians of military organisations, and their families, as well as to answer to the incumbencies related to the activities of moral education undertaken within the Armed Forces’.Footnote 87 In practice, it translated to chaplains conveying to young soldiers on the frontline that pacification was part of a divine plan to bring civilisation to urban peripheries.Footnote 88 According to Jonas:

I had an internal function, to give support to the troops, and there is a psychological dimension to this. They were very debilitated, they had little leisure time. At some point they didn’t even shower anymore, only wanted to sleep. They were on their feet the whole day with the sun burning … Stress all day long, and there were fewer soldiers than what was needed in the territory … There was a soldier who died, and in my opinion when his body arrived, it looked like he had killed himself, but the press said it was an accident. So, it’s an explosive combination, a lot of demand, discipline, and guns in hands.

As confrontations with criminal factions soared in 2013 and 2014, with some resorting to guerilla-style attacks on military outposts, the cycle of violence that ensued led Jonas to abandon his military career. In his own words:

I said to myself, I won’t justify this. My role there was to legitimise this, you understand? For the troop but also for the population. I won’t do this anymore, I give up. I left in 2014 … Because I was being instrumentalised, you know? … a good part of my job in the army was to convince the boys that they were sent by God, they wanted me to do that. Sent by God for pacification, it’s a divine call to pacify, a vocation. And that there was the other side which represented absolute evil, [people] who wanted the downfall of the territory.

On the external front, chaplains were enlisted as community brokers tasked with broader counter-insurgency initiatives. Their role was to cultivate trust among religious leaders in order to legitimise the pacification project and to act as intelligence gatherers on criminal activities. Jonas commented that the army started making meetings to invite religious actors to become informal mediators or ‘ambassadors’ of the army in the territories. In turn, they would provide access and mediation with the population. Military chaplains were thus transformed into counter-insurgency agents whose work developed on two lines:

The first is to consider local religious [leaders] as those who are more legitimate and trustworthy local voices … as they wouldn’t have any connection with crime or politics. Thus, when local demands or feedback on the operation were to be heard, they would bring in religious [actors]. The second is through joint actions, where the army would provide the necessary infrastructure to organise large, religious events.Footnote 89

Among the ‘products’ developed by the military on this front were: local events celebrating specific holidays such as Easter, Christmas, and Children’s DayFootnote 90; training courses to engage religious leaders in ‘peace culture’, covering topics such as conflict mediation, drug addiction, and domestic violence; the creation of chambers where religious leaders could express community demands to the occupying forces and public authorities; ecumenical meetings at the Pacification Force’s base; and the promotion of reflections about the pacification process during masses.Footnote 91 While both Catholics and Evangelicals had been mobilised for these activities, the military ended up prioritising Evangelical leaders given their stronger base-building networks in the territories as well as their ideological convergence with the strategic aims of the mission.

Such was the depth of this type of engagement that in 2018 the army published its own doctrine for the mobilisation of religion in operations. Titled Campaign Manual: Religious Assistance in Operations,Footnote 92 the doctrine acknowledges the strategic dimension of the military chaplaincy, or ‘the religious legitimacy to directly contribute with the mission’s success’.Footnote 93 The manual considers two roles for chaplains in military operations. First, that of a religious minister who works to ‘nourish the spirit, assist the ill, and participate in funerary honours’.Footnote 94 While the latter two are related to more conventional pastoral activities, the task of ‘nourishing the spirit’ receives a more detailed elaboration. Its purpose is, among others, to ‘mitigate the stressing effects of continuous action in operations’, ‘trigger competencies of spiritual nature that contribute as mechanisms of confrontation and overcoming of internal conflicts’, and ‘contribute to dissipate dichotomies or ethical dilemmas in face of the difficult and complex decision to kill’.Footnote 95

The second role is that of that of advisor to the Commander, which involves advising on:

the impact of religion within their unit and on the specificities of the religious environment in the area of operation that may affect the mission’s fulfilment. This can include native religions in the area of operations; sacred days that may affect military operations; and the importance of local religious leaders and structures.Footnote 96

Here, the military chaplain is considered as a sort of operations’ ethnographer who (1) surveys ‘information about ethical, moral, and religious issues, which can be of interest to the command’;Footnote 97 (2) has ‘functional knowledge of world religions and the dynamic religion of native populations, afro-descendants, nomads, immigrants, and equivalent’;Footnote 98 and (3) ‘preserves memory’ by ‘gathering and analysing facts that are transformed into information and, from this, contributes to knowledge production’.Footnote 99 Not only does the military chaplain assist in this form of intelligence-gathering service,Footnote 100 it is the chaplain’s responsibility to be directly involved in the psychological front of operations, working closely with the command to ‘settle religious, moral, ethical, and cultural issues related to the programs, civic-social initiatives, exercises, and operations’.Footnote 101 In this sense, the military chaplain is a key instrument in winning the hearts and minds of the local population:

the knowledge of local religious beliefs and its repercussions in the relationship of the troop with the population are fundamental in the formation of public opinion. Military chaplains facilitate the relationship with religious leaders and military Commanders.Footnote 102

This knowledge is then brought back to the ‘Information Operations’ division, where the military chaplain obtains ‘orientation around the ideas-force discussed in the contact with local religious leaders or councils, and which are of interest to the Command, aiding in the formation favourable opinions to operations’.Footnote 103 The emphasis on forming positive public opinion is once again emphasised in the chaplain’s responsibility to ‘integrate communitarian and Civic-Social Actions’, where ‘religious assistance collaborates with the effort of the Command in conquering support from authorities and the population via the provision of religious tasks such as weddings, baptisms, confessions, counselling, among others’.Footnote 104

If this military doctrine reflects an acknowledgement of the centrality of religion in modern-day military operations, as well as the importance of the shifting religious landscape in urban Brazil, it leaves out another important dimension of the experience of pacification in Rio: a politically conservative project of order-building that can be translated as a civilising and spiritually redemptive mission.Footnote 105 Pacification bundled notions of territorial liberation with ‘moral and spiritual liberation’ from crime through the use of force, militarised prayer, and the ideal of citizens converting to both Christ and the state order.Footnote 106 Reports and discourses by military officials during the occupation cast favelas as unruly places. According to one Force Commander, the military’s work was to:

show the population that another form of life exists … It is an enormous cultural work to change this reality. The message of pacification is that there is a pacific and orderly way of life … So if their wish is to live as they do now, they can maintain this, we are giving this instrument to them; the security institutions are entering, the state enters with other structures: school, education, sport, infrastructure, water, sewage, litter, energy, wellbeing. This is progressive, does not come from night to day, and it is the choice they make. Is this what you wish, or would you rather go back to the previous stage?Footnote 107

Bernardo (fictional name), a researcher with over a decade of fieldwork experience in the Alemão and Maré, had the opportunity to participate in official meetings held between military officials and religious leaders and to speak to key military strategists. He claimed that aside from the institutional dimension, many officials themselves espoused a religious justification for the pacifying operations. In his own words, there was a widespread view shared among officials:

as if God had placed them in the army to fulfil a mission of the Kingdom of God. I remember seeing a uniformed colonel wielding a rifle at hands and shouting: ‘[Favela] Complex for Jesus!’ So these individuals, as military, believe that God opened a door for them, the armed wing [of the state], and gave them the power to bring the Kingdom of God – under bullets or force if necessary.

Jonas expressed a similar perception: ‘I think there is really this view [in the army] that these territories are decayed, taken by evil, and in need of salvation.’ A colonel who was commanding operations in Maré had told him, ‘“I entered Maré and could feel spiritual oppression, you know? The dirt, lack of order, social order.”’ For churches participating in the partnership with the military, such a vision could not resonate better. Having negotiated with many churches for support to the military occupation, Jonas recalled the average perception of religious leaders about the occupation:

‘Now we have a collaborator in the task of redemption for the territory and its residents. We have someone joining us to … break away from the claws of evil, the enemy – who is the devil, named in the Bible as the enemy – and deliver Good and order.’ The partnership was [for them] very natural, and even though there was an official convocation, from the moment [religious] people discovered the project, they embraced it. It was an added effort to save Alemão … State and religion together, the cross and the sword.

Moreover, Bernardo claimed that what the army was proposing was a conservative model of citizenship in which subjects would be obedient to the ruling order, would not engage in ‘sexually promiscuous behaviour’ nor contest the standards of traditionally verticalised, patriarchal, authority – a suite of characteristics that ‘pleases the military worldview of society’ as well as the Evangelical.

Pacification and the strengthening of the far right in Brazil

Despite widespread consensus among analysts that Brazilian pacification in Port-au-Prince and Rio failed, these experiences yielded important returns for the military. Besides the modernisation of equipment and technical learning curves in urban operations, one of the most important results of MINUSTAH and UPPs was the return of the military into national affairs and the political mobilisation of a military elite that had not occurred since re-democratisation.Footnote 108 According to General Heleno, MINUSTAH was a ‘fundamental experience for the current generation of officials in the Brazilian Army’, providing the Brazilian troops with more management knowledge in periods of crisis and allowing them to know better ‘their capabilities’, including that of leadership.Footnote 109 According to Bernardo, the military was:

for decades looking for a space of re-signification. They tried first with the Amazon – ‘the Armed Forces as protectors of the Amazon’ – but it didn’t work. But then came Haiti and later Alemão and Penha. Luciano Hulk [a popular TV host] dedicated a full show to the army. Then Esporte Espetacular [a weekly sports TV programme] also dedicated a full show about Haiti. All TV networks were giving fuel to it. It became the theme of a primetime soap opera, Salve Jorge, about an army captain who was in Alemão. Even Prince Harry visited the Alemão Complex in 2012. And in Haiti, they were in contact with a universe of global NGOs and international organisations such as the UN. All this was just hatching the snakes’ egg.

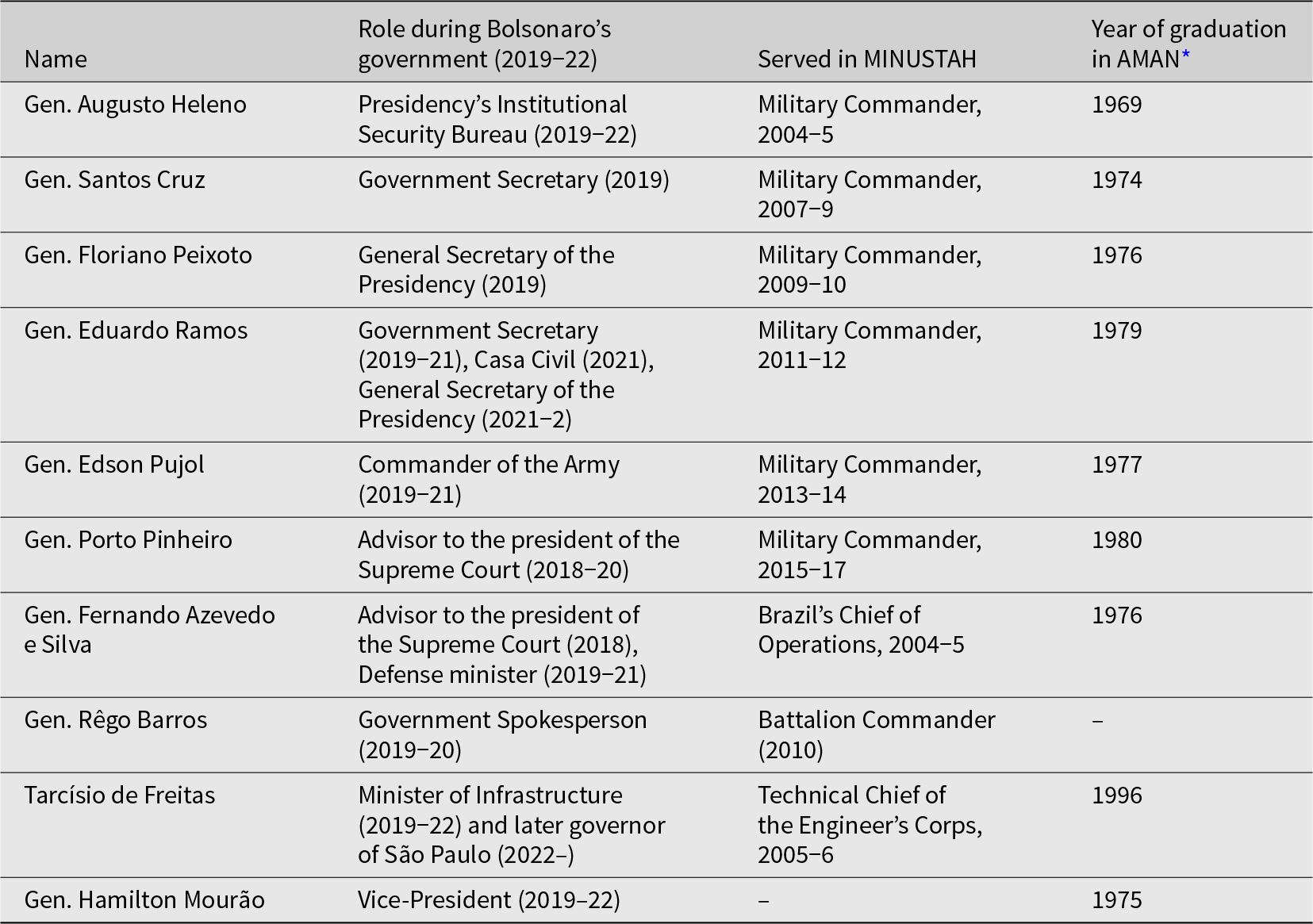

During Bolsonaro’s government, this military elite occupied key political positions in the state (see Table 1).Footnote 110 Generals who were Force Commanders in Haiti became top-tier ministers, such as Floriano Peixoto, who became General Secretary of the Presidency of the Republic; Fernando Azevedo e Silva (Defence Minister between 2019 and 2021); Santos Cruz (Government Secretary during the first semester of 2019 and later a critic of Bolsonaro); Eduardo Ramos (Government Secretary who succeeded Santos Cruz). General Augusto Heleno, the first Force Commander of MINUSTAH, was Bolsonaro’s right-hand man, leading the Presidency’s Institutional Security Bureau (Gabinete de Segurança Institucional, GSI) between 2019 and 2022. Otávio Rêgo Barros, another MINUSTAH veteran who later commanded the Pacification Force in the Alemão Complex, and who oversaw the military–religious partnership, was the government’s spokesperson between 2019 and 2020. General Walter Braga Neto – who was the Commander of the East Military Command in Rio de Janeiro during the occupation in Maré and then became the intervenor of the Federal Intervention in Rio in 2018, which effectively succeeded UPPs, held several posts. He was chosen as Chief of Staff between 2020 and 2021, Minister of Defence between 2020 and 2021, and then Bolsonaro’s running mate in the 2022 elections. Tarcísio de Freitas, a captain who served at MINUSTAH, was Minister of Infrastructure from 2019 to 2022 and was recently elected as the São Paulo state’s governor in the 2022 elections. De Freitas recently made the headlines by saying he was ‘extremely satisfied’ with a police operation in a poor neighbourhood in Guarujá, São Paulo, in which the police left 16 dead. He claimed that ‘there was no excess’ in the operation.Footnote 111

Table 1. High-ranked officials who served in Port-au-Prince and Rio and then in Bolsonaro’s government.

* Academia Militar dos Agulhas Negras (AMAN) is the largest graduation centre for combatant officers in the army. Source: the authors.

As can be seen in Table 1, the majority of officials graduated in the 1970s, at the height of the military dictatorship. Although some of these names left the government and became critical voices against Bolsonaro, others, such as Heleno and Braga Neto, remained loyal allies and were key articulators of the democratic backsliding process, including a coup plot after Bolsonaro lost the elections in 2022.Footnote 112

Besides this recapture of politics by a group of the military elite, the MINUSTAH and UPPs experiences also became crucial sites of experimentation with a range of policies that would later become the hallmark of Bolsonaro’s political agenda. Bolsonaro’s hard-line public security platform had in Haiti a ‘testing ground’, where it was able to be put into practice, improved upon, then reintroduced in Rio de Janeiro, and reapplied by the Federal Government under Bolsonaro and his group of peacebuilding and pacification veterans.Footnote 113

Members of the armed forces with experience in MINUSTAH frequently complained about what they understood as a limited authorisation to deploy use of force during GLO operations domestically.Footnote 114 Compared to the latitude and protections granted to them by the rules of engagement in MINUSTAH, they felt frustrated with the possibility of facing legal consequences, which effectively occurred after the Federal Intervention in Rio de Janeiro in 2018 – authorised under a GLO provision. During such operations, the military was not legally authorised to make arrests or searches in houses solely on the basis of suspicion or intelligence reports. Further, authorisations to engage in exchange of fire was also limited, as troops could only respond to hostilities in self-defence. In contrast, MINUSTAH, a Chapter VII mission, permitted the use of lethal force beyond self-defence, allowing troops to employ it to achieve mission objectives.Footnote 115 The experience in both environments led to a growing demand by the military to widen the legal scope of their actions:

As the military experienced that comparatively fewer restrictions in rules of engagement and more legal protection for soldiers in MINUSTAH were key factors for what they consider a successful mission, they aim to re-import this framework to their internal role.Footnote 116

In an interview for Jornal Nacional – the largest newshour programme from the Globo corporation – during the 2018 presidential campaign, Bolsonaro referred to the initiatives developed by the Brazilian military in Haiti as a ‘success’ and a model to be reproduced in Brazil during operations to deal with organised armed groups in marginalised urban areas.Footnote 117 In fact, the complaints about perceived legal limits of action in domestic public security operations were taken up as one of the main agendas during Bolsonaro’s 2018 and 2022 presidential campaigns. In the same interview, Bolsonaro defended the creation of excludente de ilicitude (exclusion of unlawfulness), a measure to exempt or reduce punishment for security agents engaged in lethal armed conflict. In November 2019, Sergio Moro, then Bolsonaro’s Minister of Justice and Public Security, sent a bill to Congress to include the concept of legitimate self-defence for military and public security officers engaged in GLO operations. The bill stated that ‘there is no crime when the agent practises the fact: in a state of necessity; in self-defence; in strict compliance with legal duty or in the regular exercise of rights’. The project was ultimately rejected, and, in April 2023, Lula’s government withdrew it from Congress.Footnote 118 In February 2019, another bill submitted by Moro attempted to broaden the concept of self-defence by including acts committed out of ‘excusable fear, surprise or violent emotion’. The measure was widely criticised by public security experts and human rights organisations and was subsequently archived later that year.Footnote 119

Despite the broad reporting of human rights violations committed by MINUSTAH personnel – such as sexual abuse, exploitation of women and children, physical threatening of civilians, and disproportionate force – there has been thus far no forms of accountability or reparations to victims.Footnote 120 Similar patterns have been observed in Rio de Janeiro’s UPP project.Footnote 121 In both realities, the military intervention and occupation were based on a perception of them being spaces of violence and exceptionality. This favoured a logic of war and death epitomised by General Heleno’s infamous remark that, in Rio, ‘the verb of the mission is to eliminate’.Footnote 122 The military understood the deaths of innocent bystanders in both operations as ‘collateral damage’, and the appraisal of different national and international stakeholders strengthened this perception.

This widespread silence regarding violations also contributed to the construction of a positive image of Brazilian peacekeepers, fostering the idea of a ‘success case’ in Port-au-Prince and Rio. This, in turn, also influenced military perceptions on domestic public security operations, their view of themselves as a competent ‘political moderator’, with the expertise to manage political instability and social conflicts – a viewpoint which has been cultivated since the 19th century.Footnote 123

The politics of religion is another element to be taken into account. The rise of the far right in Brazil is inextricably linked to the political mainstreaming of the Christian far right. The core of this social force lies in transforming fundamentalist Evangelical and Catholic ideology into a popular political agenda. This agenda opposes progressive social movements and aims to steer state policies towards establishing a religiously infused social order based on patriarchal relations, obedience to authorities, the primacy of militarism, and the naturalisation of racial, gender, and class inequalities.Footnote 124 Bolsonaro’s government effectively weaponised these groups with the widespread use of disinformation campaigns and conspiracy theories that tapped into popular fears about crime, violence, and corruption, associating them with the threat of communism or the ‘globalist elite agenda’. The process of radicalisation that led to violent mobs storming government buildings on 8 January 2023 was equally planned, operated, and ideologically justified by military and religious groups.Footnote 125 As shown in the last section, the lines of division between them are not always clear.

Following Salem and Bertelsen’s insight that the ‘experiment with new policing practices at the UPPs can aid us in understanding the moral framework underpinning Bolsonarismo’,Footnote 126 we consider the pacification in Rio as a laboratory for engaging religious actors in political-military projects. In both Haiti and Rio, the military learned that success for operations could not rely on force alone and that mobilising symbolic elements was an effective way of bolstering ideological support for militarised forms of interventions.Footnote 127 Instead of a top-down imposition – alien to liberal peacebuilding standards and human rights sensibilities – a bottom-up engagement empowering religious networks could generate intelligence gains and shield the military from external criticism by social movements opposing the occupation, as well as deflecting media pressure.

The fact that an official doctrine was published in 2018 enshrining the principles of engagement with religious groups in operations is no coincidence. It shows that the accumulated experience in Rio has been carefully considered by military strategists, in a context of intense politicisation of Evangelicals at the national level. Although Bolsonaro’s government drew support from various ideological sources and social groups, a number of scholars have highlighted that the far-right government should be regarded primarily as a military government. They contend that the higher echelons of the military instrumentalised Bolsonarismo for their own goals and guided many of the government’s policies.Footnote 128 This is no stretch of imagination, as Bolsonaro himself was a former army official and was spotted attending meetings with military leaders before he was officialised as a presidential candidate. Lentz and Penido have suggested that this broader military–religious nexus is also reflective of internal dynamics to the military, such as shifts in recruitment processes that favour demographic growth of Evangelicals within the ranks and convergence between the military’s National Security Doctrine and Christian conservatism.Footnote 129

Exactly how much the military guided the religious affairs of the government is something that warrants further research, but there is evidence that this was pursued by the above-referenced military elite. In an interview with the press in July 2019, General Rêgo Barros, who oversaw the military-religious project in Rio, claimed that the government would ‘naturally seek an ideological alignment [with Evangelicals], which is something natural for those who have in the core of their daily lives the values of family, values against corruption, which is what our country needs so much’.Footnote 130 General Braga Neto, during a campaign rally in an Evangelical church before the second round of the elections, said to the audience that ‘we are all brothers in Christ. I believe in the prophecy that Brazil will be the fatherland of the Gospel. I really believe it. This is not politics, ok?’Footnote 131 Then, he made an association between moral values – which in his views were being destroyed by ‘gender ideology’ – and warfare:

I have been in war, I was in East Timor during combat, and I realised that those who suffer the most are children, the elderly, and women … And I began to worry a lot about children, because I saw many children suffering, both abroad in [East] Timor and in the communities in Rio, where, you know, I was the federal intervenor … [During the intervention] I also learned this: to destroy is easy, but to reconstruct is very difficult.Footnote 132

Reconstruction, or order building, is precisely what pacification operations and doctrine entail.Footnote 133 However, just like in the UPP experiment, Braga Netto was associating the task of reconstruction with the spread of moral religious values. Underpinning this approach is an embrace of the logic of proximity or community policing,Footnote 134 in which the reconstruction phase of pacification implies building trust relations with the population and attending a local community’s needs. Whereas in the case of Rio’s pacification community policing was translated as a conservative alliance with Evangelical organisations, the same process can be observed elsewhere in the country in terms of policing, with many military police forces utilising the Evangelical military chaplaincy to achieve similar goals.

In São Paulo, for instance, the Association of Evangelical Military Police Officers, known as PMs de Cristo (or Officers for Christ), has become the de facto military chaplaincy of the state and since 2015 has established a partnership with the state government to work on community policing projects. According to PMs de Cristo ideologues, community policing is an instrument to ‘orient political transformations’Footnote 135 and the police chaplain, a community broker who can ‘potentialise what is good in society’ so that ‘evil doesn’t take hold of public spaces’.Footnote 136 PMs de Cristo, alongside many other Evangelical police associations across the country, have been key articulators of far-right politicisation within military police barracks.Footnote 137 According to a recent survey, Evangelical police officers have been disproportionately more engaged in online radical activities compared to officers from other religions, agnostic, or atheists.Footnote 138

In Brazil, the introduction of community policing has been hailed as the strengthening of democratisation processes within police institutions and regarded as an important step in modernising security governance to include human rights provisions. Since the 1990s, many military police organisations have undergone institutional reforms and incorporated community policing as a move to distance the image of the police from the authoritarian era. The same logic was present in the military’s engagement in Port-au-Prince and Rio. Incentives for participating in MINUSTAH were part of Lula’s broader foreign policy strategy, utilising the discourse of ‘non-indifference’ and ‘solidarity diplomacy’ to participate in cooperation initiatives and peacekeeping operations with the active role of the Ministry of Defence.Footnote 139 For the Workers’ Party governments, this was also an opportunity to set a new role and public image for the military as an institution guided by human rights principles. The National Defence Strategy of 2008 and the White Book of National Defence of 2012 were official documents that reflect attempts to create a democratic and transparent defence policy.

While community policing and the local turn in the Brazilian military’s international and domestic operations received political support from progressive sectors, these mechanisms were reappropriated as counter-insurgency assets on the one hand, and as a means to enable political projection, on the other. Jonas’s testimonial is instructive here. As a military chaplain during the occupations in Rio, he began his career ‘believing in that which in Public Security people call proximity policing’. In reality however, the experience turned out to be a lot different:

When you see the thing in locus, I became disillusioned completely, and that’s when I left the army. So many things can go wrong, I don’t even know where to start. You expose locals, whoever supports you is exposed … You invite some people to take part in the project, some accept it willingly, but within a year the army leaves [the territory]. There was a pastor who dived deeply in the project with us, but as soon as the army left, he had to flee from the territory. He called me and I couldn’t do anything. What was I supposed to do, put him inside my house?

This passage reflects not only the failure of the military occupation – which, as soon as the military left, opened ways for criminal organisations to rearticulate territorially and seek revenge against supporters of the occupying forces – but also how the instrumentalisation of religious leaders fell short of introducing better public services for the population. Describing similar cases in the United States, Griffith argues the ‘social sentimentalization of community policing’ by Evangelicals does not ‘fundamentally challenge the power, funding, or deployment of police as a response to social problems that could be addressed in other ways’.Footnote 140 In fact, in Brazil it has been an important pathway to strengthening the far right.

Closing remarks

This article explored the connections between Brazil’s recent contribution to peace processes and the rise of the far right. While much scholarship examines how authoritarian tendencies in conflict-ridden nations may be intensified by peacebuilding, this study has shed light on how liberal peacebuilding can contribute to authoritarianism and de-democratisation within the deploying nation itself.Footnote 141 This phenomenon is exemplified by the connections between Brazil’s leading role in the pacification of Port-au-Prince and Rio de Janeiro and its effect on strengthening the process of far-right mainstreaming.

The contradictions of the liberal project of promoting democracy, social justice, and human rights through a militarised logic have brought different results compared to those announced by the official optimism in both Port-au-Prince and Rio. Pacification efforts ultimately meant a strong resort to military and repressive actions. Praise for the military and its ‘robust actions’ in Haiti, without accountability, led to growing demands for a relaxation of the internal rules regarding the use of force by domestic security actors. Violent militarism became one of the hallmarks of Bolsonaro’s government, a trait significantly moulded by the military’s pervasive presence in critical civilian posts. As shown, veterans from Port-au-Prince and Rio became some of the most important agenda-setters in the far-right administration.

Another key vector of this was the mobilisation of religion in the pacification of Rio de Janeiro. The military strategically engaged with religious actors, both internally to boost troop morale and externally to bolster legitimacy for the occupation and as a mechanism of intelligence gathering. This engagement extended to the development of a doctrine recognising the crucial role of religious assistance in operations. Underlying this experiment was a politically conservative project, characterised by a civilising mission entwined with a spiritually redemptive discourse as part of the military’s blueprint for order-building. The military-crafted vision of pacification depicted favelas as places in need of salvation, a narrative embraced by both officials and religious leaders. According to Salem and Bartelsen, at the UPPs, ‘increasing police [and military] involvement in favela sociability reflects broader trends toward a reconfiguration of the social through the logic of security – including the merging of security politics with right-wing moralism and reactionary discourses on gender, sexuality, and race’.Footnote 142 Thus, we have argued that one way in which the far right has been strengthened in Brazil is through the Port-au-Prince–Rio connection. While it certainly did not cause the rise of Bolsonarismo – which also draws on other ideological sources of legitimation and social bases – both experiences prefigured the ways in which Bolsonaro’s government later capitalised the politics of militarism and religion as a far-right platform.Footnote 143

However, the origins of these dynamics were already being created in the heart of democracy and under the progressive governments of the Workers’ Party. With the military elevated to a position of national political significance, it embraced, at least in theory, the core principles of liberal peacebuilding, adapting its own doctrines to reflect new global standards enshrined in the local turn in peacebuilding. The result, however, was a conservative reappropriation of these principles, which were used to advance military counter-insurgency rather than a commitment to contribute towards the development of marginalised communities. This points to the need to further investigate the nuanced forms with which liberal peacebuilding and counter-peace dynamics are co-produced in a hybrid fashion, as well as the impact of peacebuilding in the deployer country.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Ana Cortez and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Ethical standards

The interviews utilised in this research were part of Rodrigo Campos’s PhD fieldwork, and their inclusion in this journal article was conducted in strict adherence to ethical standards. Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Economics, Law, Management, Politics, and Sociology Ethics Committee (ELMPS), of the University of York, on 9 November 2021.

Rodrigo Campos holds a PhD in Politics from the University of York, having previously conducted his MA and BA in International Relations in his home country, Brazil. He currently works as a post-doctoral researcher at the ESRC ‘Vulnerabilities and Policing Futures Research Centre’, on a project about the politics of volunteer groups in policing. His main research interests include far-right politics, Brazilian militarism, religion, and security, and global Evangelicalism.

João Fernando Finazzi holds a PhD and Master’s degree in International Relations from the Interinstitutional Graduate Program in International Relations San Tiago Dantas from the São Paulo State University (UNESP), the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), and the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP). He previously worked as a lecturer at the Pontifical Catholic Universities of Minas Gerais (PUC-MG) and São Paulo (PUC-SP). He is a member of the Research Group on International Conflicts (GECI/PUCSP).