Introduction

The Travels of Marco Polo is an important but questionable historical document (see, for example, Moule & Pelliot, Reference Moule and Pelliot1938: 41; Jackson, Reference Jackson1998: 84–86). This account of lengthy travels along Eurasian land and sea routes around the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries ad constitutes a key document for historians to decipher about the perception of the multicultural society that Polo encountered on his way to China. But the authenticity of Polo's travels, in particular his ‘visit to China’, is still an issue that contemporary historians debate: for instance, many scholars (Yule & Cordier, Reference Yule and Cordier1903; Penzer, Reference Penzer1929; Olschki, Reference Olschki1960; Franke, Reference Franke1966; Haeger, Reference Haeger1978; Wood, Reference Wood1996) argue that Marco Polo did not actually visit many of the localities which he claims to have seen on his journey, including Burma, the Arabian Sea, the Indian subcontinent, Java, and some cities in China; and that Marco Polo reported hearsay about China acquired in Italian merchant colonies positioned around the Black Sea. But supporters of Marco Polo argue (De Rachewiltz, Reference De Rachewiltz1997; Haw, Reference Haw2006) that his return journey from China has been historically recorded in Chinese history and Arab accounts (Yang & Ho, Reference Yang and Ho1945; Pelliot, Reference Pelliot1959–73), and that his detailed descriptions of paper money and salt production provide supporting evidence of his visit to China (Vogel, Reference Vogel2012). The mid-point in this debate argues that Marco Polo did in fact visit China, but that he exaggerated and falsified details about his visit and sojourn: for example, it is possible that Marco Polo did serve in the Imperial Salt Monopoly in Yangzhou, but not as a governor (Morgan, Reference Morgan1996: 233).

This historical debate has not been considered by archaeological studies for many decades. Given that it is such a short-lived historical event, no (or rare) archaeological evidence can be found to link to the travels of Marco Polo. The only discussion on the material culture associated with Marco Polo was undertaken by Oscar Raphael (Reference Raphael1932), when he visited the Basilica of San Marco in Venice. He suggested that a Chinese Qingbai porcelain jar housed in its Treasury was probably brought back by Marco Polo from China (Raphael, Reference Raphael1932; Dubosc, Reference Dubosc1954: 156, cat. no. 565) (see below for a detailed description). Although this has been widely accepted by many archaeologists (Whitehouse, Reference Whitehouse1972: 71–72; Morgan, Reference Morgan1991: 71; Horton et al., Reference Horton, Brown and Mudida1996: 310; Flecker, Reference Flecker2003: 397–98; Kennet, Reference Kennet2004: 63), no further research has examined the manufacturing and dating evidence for this so-called ‘Marco Polo jar’ and similar ceramic finds (so-called ‘Marco Polo wares’) from archaeological sites of the Indian Ocean. It is therefore understandable that, because of the lack of material evidence and discussion, archaeologists have been reticent to engage in the debate over Marco Polo's visit to China.

This article examines the distribution of ‘Marco Polo wares’ across a wide geographical area. It suggests a hypothetical date of the ‘Marco Polo jar’ on archaeological grounds and revisits the production of Chinese ‘Marco Polo wares’ and their consumption across the Indian Ocean. In addition, Marco Polo’ visit to China is re-evaluated.

The Current View: Why is the Dehua Qingbai Porcelain Jar Associated with Marco Polo?

In terms of material cultural evidence, a Chinese Qingbai porcelain jar, known as the ‘Marco Polo jar’, housed in the Treasury of San Marco in Venice, may be the only artefact linked to Marco Polo and his visit to China. This jar is about 12 cm tall, with a maximum diameter of 8.1 cm, a low foot-ring, and a short neck with four small loop-shaped lugs. It has a hard, white, thin body that is coated with Qingbai (青白 literally: bluish white) cream glaze. There are four zones of decoration presented in relief on the surface of the jar, consisting of two bands of floral scrolls in the middle and two bands of petal-like motifs near the top and bottom of the jar (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The ‘Marco Polo jar’ housed in the Treasury of the Basilica of San Marco in Venice (photograph by Lin Meicun).

Originally it was suggested that this Qingbai porcelain jar had been brought back by Enrico Dandolo (Doge of Venice) from St Sophia after the fall of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade of ad 1204 (Raphael, Reference Raphael1932: 14), but initially Oscar Raphael had argued that this dating was too early, following an examination of the shape of Yuan Chinese ceramics (ad 1276 to 1368) (Raphael, Reference Raphael1932: 14). The San Marco jar was associated with Marco Polo because its dating matches the era of the travels of Marco Polo, and therefore might be the only surviving piece of Marco Polo's treasures reputed to have been brought back from China to Venice in ad 1295 (Raphael, Reference Raphael1932: 14). Raphael further suggests that this jar may have been produced in the Dehua kilns in Fujian province in southern China (Raphael, Reference Raphael1932: 13–14). And his argument may be supported by similarly shaped Qingbai stonewares found in vast numbers in many local kilns in Fujian province (Dehua Guciyao Kaogu Fajue Gongzuodui, 1979; Ke & Chen, Reference Ke and Chen1995; Ye, Reference Ye2005).

As for the wider archaeological context, many Dehua Qingbai porcelain fragments of a type similar to the ‘Marco Polo jar’ have been found on archaeological sites and shipwrecks in the Indian Ocean (see below for detailed discussion). It has been suggested that these ceramic finds be called ‘Marco Polo wares’ (Ayers, Reference Ayers1988: 16–17) and this term has been adopted by archaeologists. However, because these findings seem to be ambiguously defined, poorly dated, and vaguely described, confusion has arisen when archaeologists have attempted to understand their chronology. Some basic attempts have been separately made by Whitehouse (Reference Whitehouse1972: 71–72), Morgan (Reference Morgan1991: 71), Horton et al. (Reference Horton, Brown and Mudida1996: 310), Flecker (Reference Flecker2003: 397–98), and Kennet (Reference Kennet2004: 63), who believe that many of these wares were made in the Dehua kilns, Putian kilns, or Anxi kilns in the Fujian province of southern China, following the examples published by Hughes-Stanton and Kerr (Reference Hughes-Stanton and Kerr1980: no. 186). However, no further evidence has been discussed on the parallel production of ‘Marco Polo jars/wares’ within the Chinese ceramic industry.

Historical and Archaeological Evidence for the ‘Marco Polo Jar’

Initial historical discussions of Marco Polo's travels in China have emphasized the Dehua ceramic industries witnessed by Polo (Feng, Reference Feng2001: 375–80; Xiong, Reference Xiong2006: 28), but no study establishes the link between these historical accounts and the archaeological evidence. A general review, from the production of Qingbai porcelain wares in China to their consumption in the Indian Ocean during the era of Marco Polo, serves here to provide a wider geographical overview of the current historical and archaeological evidence.

Description of the ceramic industry in Southern China by Marco Polo

In modern English, the word ‘porcelain’ is thought to have been coined by Marco Polo from ‘porcellino’, which in Italian refers to the piglet-like shape of a cowrie shell, hence a translucent shell. For the first time, Marco Polo linked Chinese ceramics to a thin, white shell to describe porcelain (Hamer & Hamer, Reference Hamer and Hamer1975: 229). Marco Polo claims to have had a chance to view the Dehua kilns in Fujian province, the original manufacturing place of the ‘Marco Polo jar’.

In the Travels of Marco Polo, there are two places that are linked to Chinese ceramic manufacture: ‘Zayton (Zai-tun, Zarten, Zai-zen, Caiton or Tsuen-Cheu)’ and ‘Tingui (Tiunguy, Tin-gui or Tin-giu)’ (see Wright, Reference Wright1854: 343–46; Feng, Reference Feng2001: 375–80; Cliff, Reference Cliff2015: 221–24). Marco Polo wrote:

‘The river that flows by the port of Zai-tun is large and rapid… At the place where it separates from the principal channel stands the city of Tin-gui. Of this place there is nothing further to be observed, than that cups or bowls and dishes of porcelain-ware are there manufactured.’ (Wright, Reference Wright1854: 345)

The identification of the port of Zayton is now agreed to be Quanzhou port (泉州港), which was one of largest sea ports in southern China at that time. The name ‘Zayton’ comes from the Arabic name for Quanzhou, and represents the trees called Citong (刺桐, Erythrina variegate, or the Tiger Claw Tree), which were planted around the city walls (Feng, Reference Feng2001: 378–79; Cliff, Reference Cliff2015: 387, note 64). On the other hand, the interpretation of Tingui varies. For example, it has been thought to be ‘Tingzhou (汀州)’, present-day Changting (长汀), which is located near the western border of Fujian province (Wright, Reference Wright1854: 345; Cliff, Reference Cliff2015: 387, note 66), but Feng Chengjun has a different opinion and suggests that it is Dehua City (德化) near Quanzhou. He argues that Tingui might represent the name for Quanzhou, and, geographically, that Dehua is part of Quanzhou. Marco Polo was using Zayton to describe Quanzhou port and Tingui is therefore used to describe Dehua (Feng, Reference Feng2001: 378–80).

There is parallel evidence to match Marco Polo's description concerning the southern Chinese ceramic industry, and the archaeological material seems to indicate that Dehua is correct. Indeed, from Marco Polo's description, there is nothing but the ceramics industry in Tingui City. Marco Polo further notes that: ‘Great quantities of the manufacture [of porcelain] are sold in the city, and for a Venetian groat you may purchase eight porcelain cups’ (Wright, Reference Wright1854: 345; Cliff, Reference Cliff2015: 387, note 66). The archaeological discoveries in Changting County showed that there was a small-scale ceramics industry, which mostly dates to the Song dynasty (ad 960–1274) (Deng, Reference Deng1993), i.e. earlier than Marco Polo's time. By contrast, Dehua City had a well-established ceramics industry in Marco Polo's time (Dehua Guciyao Kaogu Fajue Gongzuodui, 1979; Fujiansheng Bowuguan, 1990). In addition, as already mentioned, the so-called ‘Marco Polo jar’ in the Treasury of San Marco is thought to have been produced by a Dehua kiln. It seems therefore reasonable to accept that Dehua City is the Tingui City mentioned by Marco Polo.

The Qingbai ceramic industry in Fujian province, china

In order to better understand the ‘Marco Polo jar’ and ‘Marco Polo wares’, a comprehensive overview of the Chinese Qingbai ceramic industry is necessary (Figure 2). It is believed that Qingbai ware was first manufactured in the tenth century in the Jingdezhen kilns in Jiangxi province of southern China, and gradually became popular over the following three centuries (see Jiangxisheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo & Jingdezhen Minyao Bowuguan, 2007). With the concurrent development of maritime trade, Qingbai stoneware became a popular ceramic commodity on cargo lists. In addition to the Jingdezhen-produced Qingbai wares, the bluish-white/greyish-white wares produced in the local kilns of Fujian and Guangdong were also widely exported. Consequently, during the twelfth to thirteenth centuries there was an economic and industrial boom in the Fujian local ceramic kilns (see Ho, Reference Ho and Schottenhammer2001). During the time of this large-scale production of Qingbai ceramics in southern China, the Dehua kilns in Fujian province became important for producing moulded Qingbai ceramics in the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries (see Dehua Guciyao Kaogu Fajue Gongzuodui, 1979; Fujiansheng Bowuguan, 1990; Lin & Zhang, Reference Lin and Zhang1992: 564).

Figure 2. A sketch map of the Chinese ceramic industry and locations of Qingbai ceramic producers in Fujian province during the fourteenth century (drawing by Ran Zhang).

The history of Qingbai stonewares at the Dehua kilns can be traced back to the early twelfth century and production continued up to the sixteenth century (Dehua Guciyao Kaogu Fajue Gongzuodui, 1979: 57; Chen, Reference Chen1999; Fujiansheng Bowuyuan, Dehuaxian Wenwu Guanli Weiyuanhui & Dehua Taoci Bowuguan, 2006). There are two major kiln sites that have been excavated: the Wanpinglun kiln site (碗坪仑窑址) (see Fujiansheng Bowuyuan, 1990) and the Qudougong kiln site (屈斗宫窑址) (see Dehua Guciyao Kaogu Fajue Gongzuodui, 1979; Fujiansheng Bowuguan, 1990), which can be independently dated to the twelfth to thirteenth centuries (Chinese southern Song dynasty) and late thirteenth to fourteenth centuries (Yuan dynasty: ad 1274–1368) (see Lin & Zhang, Reference Lin and Zhang1992). The moulded reliefs on the Qudougong Qingbai stoneware products can be distinguished from the wares found at the Wanpinglun kiln site (Lin & Zhang, Reference Lin and Zhang1992: 564), and are very similar to the jar housed by the Treasury at San Marco in Venice (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Drawings of Qingbai stonewares from the Qudougong site. 1) cup; 2–3) bowls with lids; 4–8) bowls; 9–10) plates; 11) jar with lid; 12) pot; 13) kendi (re-drawn by Ran Zhang, after Dehua Guciyao Kaogu Fajue Gongzuodui, 1979).

When considering the dating of the Dehua sites, it has been argued that the Qudougong kiln site is later than the kiln at Wanpinglun, and that the Qudougong site dates to the late thirteenth century and mostly the fourteenth century ad (see Lin & Zhang, Reference Lin and Zhang1992). The dating evidence for the Qudougong site is mainly based on some ceramic figures with Mongolian garments, which could suggest that the northern Chinese culture was imported to southern China during the Yuan dynasty (Dehua Guciyao Kaogu Fajue Gongzuodui, 1979: 57), and also on some pieces of kiln furniture excavated at the Qudougong kiln sites which have inscriptions in Phags-pa script (Dehua Guciyao Kaogu Fajue Gongzuodui, 1979: 57). This was a new alphabet introduced by Kublai Khan in ad 1269, and its implementation in southern China would therefore date to after ad 1274, when the Mongolian rulers conquered the whole of China. Kiln furniture fragments with Phags-pa script have also been found at the Laohudong kiln site in Hangzhou City (e.g. Wang, Reference Wang2004: 89, fig. 45) and the Longquan kiln sites in Zhejiang province (Zhu, Reference Zhu and Ting1989: 28), which can be dated to the Yuan dynasty. Finally, some clay boxes with a cyclical date of ‘dingwei (丁未)’ were unearthed at the Qudougong site, which suggest two possible years during the Yuan Mongols’ reign, i.e. ad 1307 and 1367 (see further discussion below) (Fujiansheng Bowuguan, 1990: 140–42; Lin & Zhang, Reference Lin and Zhang1992: 565).

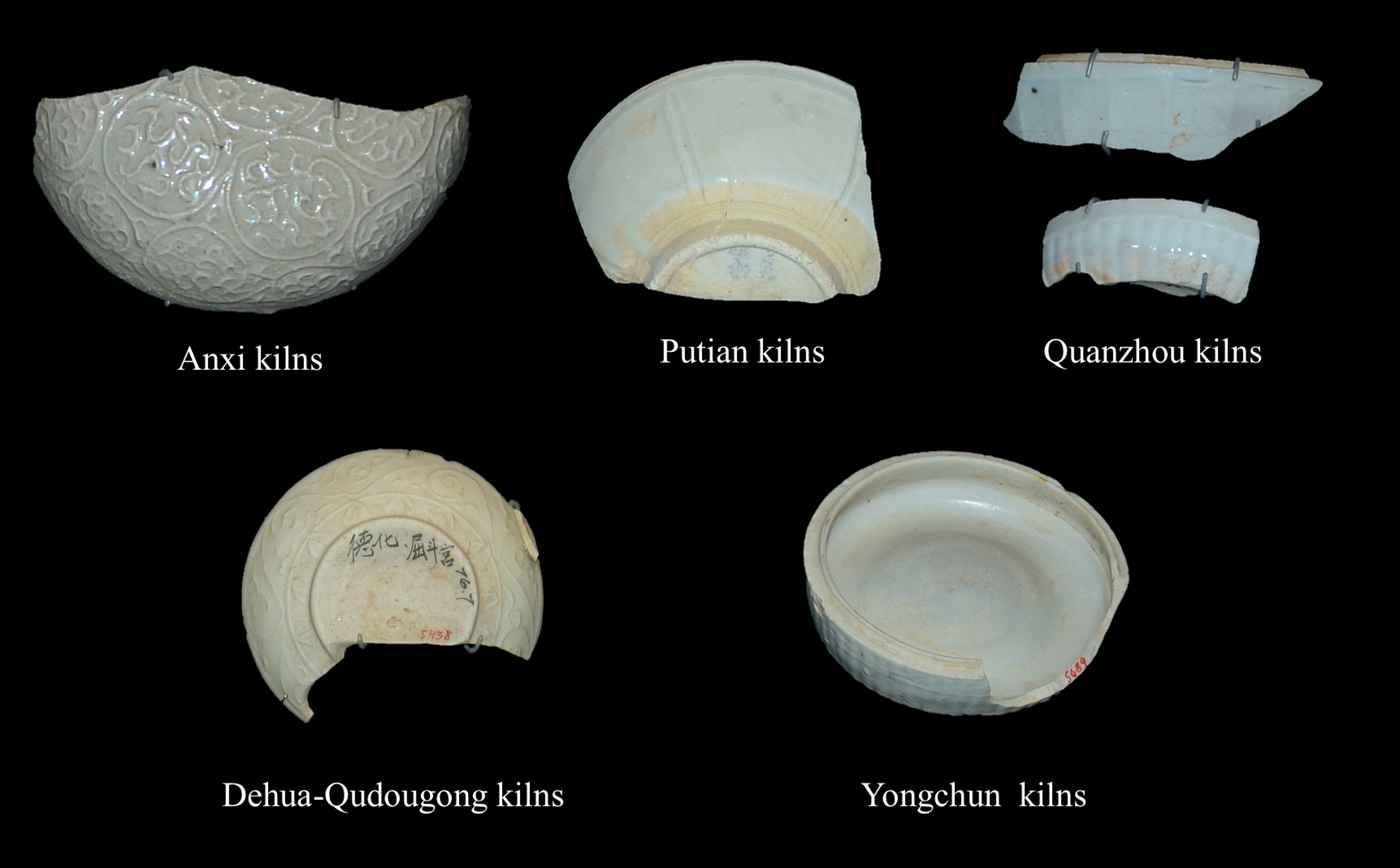

Finally, rather than just being produced at the Dehua kilns, it seems that ‘Marco Polo wares’ were widely produced in the southern Fujian province at kiln sites such as Yongchun (永春窑) (Zeng, Reference Zeng2001: 173), Putian (莆田窑) (Li, Reference Li1979; Ke & Chen, Reference Ke and Chen1995: 612), Anxi (安溪窑), and Quanzhou (泉州窑) (Li, Reference Li1960; Anxixian Wenhuaguan, 1977; Zhang, Reference Zhang1989; Lin, Reference Lin1999). The wares from these sites all seem to share the same style and firing techniques as Qingbai wares and are dated to the Yuan dynasty (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Qingbai ceramic wares from Fujian local kilns, from the collections in the Palace Museum, Beijing. © Wu Ning. Reproduced by permission of Wu Ning.

An overview of the ‘Marco Polo jar’ finds in the Indian Ocean

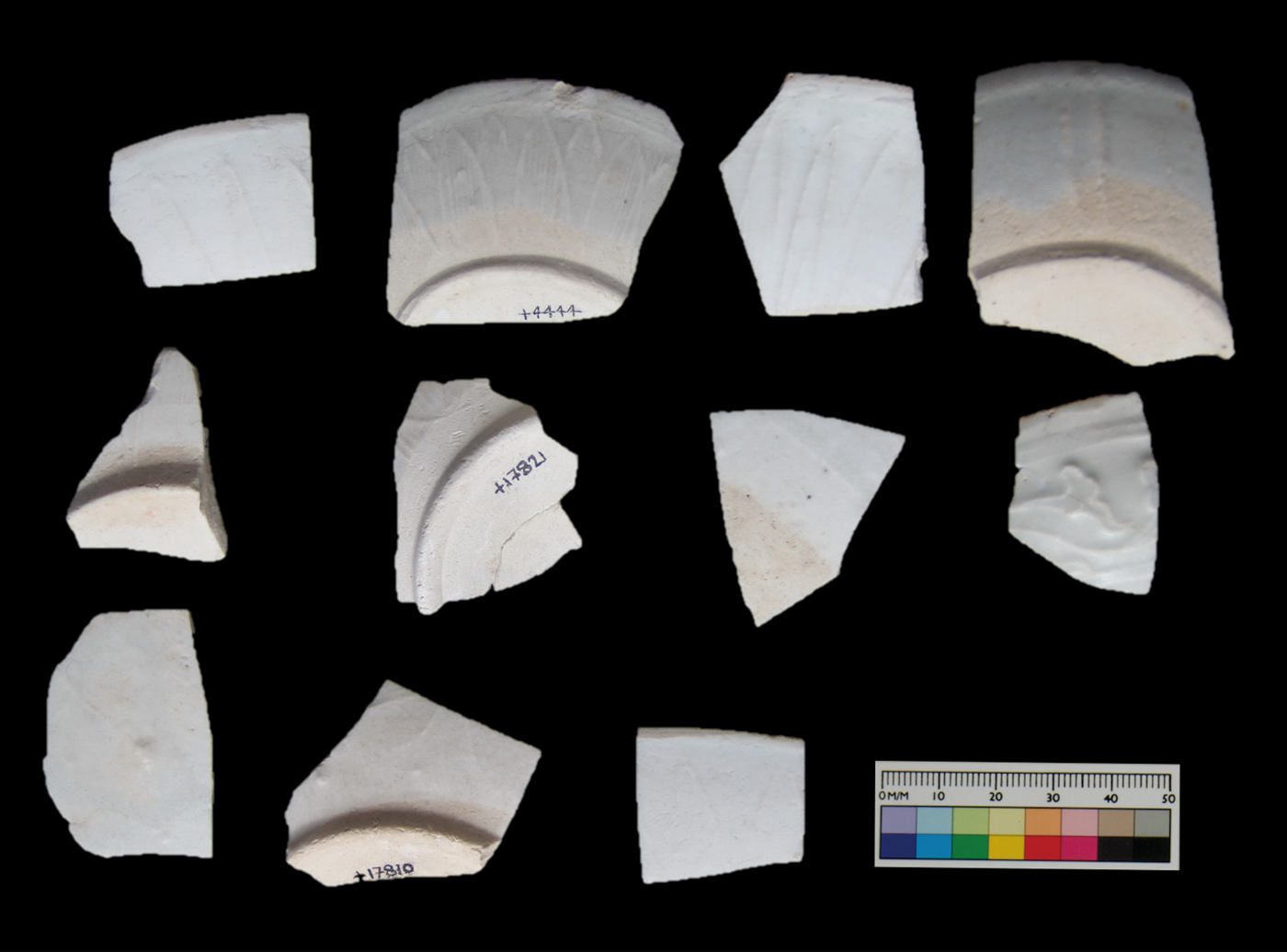

‘Marco Polo wares’ normally have a Qingbai glaze, which is thin, glassy, and not very hard. The well-fired fabric is bluish-white, but pure white, yellowish-white, and greyish-white are also found, and some wares have crazing (Dehua Guciyao Kaogu Fajue Gongzuodui, 1979: 55). In terms of shapes, the most common are bowls, bowls with a pointed body, plates, covered boxes, kendi (pouring vessels with a spout, see Figure 3.13), and jars. They are normally not very large, with the mouth diameter of the bowls and plates usually no larger than 23 cm. Unglazed rims and flat-bases are common, and some tablewares are half glazed on the outside. According to the archaeological findings from the Qudougong site, Qingbai ceramic forming, setting, and firing techniques were not standardized, resulting in variations in shape (Dehua Guciyao Kaogu Fajue Gongzuodui, 1979: 55–56). As for decorations, moulded patterns are very common and mainly consist of lines, a band of classic scroll, flowers (including decorative lotus petals, lotus, chrysanthemums, peonies, and plum blossom), clouds, and phoenixes, while on plain wares carved decorations and applied patterns can also be found (Dehua Guciyao Kaogu Fajue Gongzuodui, 1979: 57–58) (Figures 5 & 6).

Figure 5. Dehua Qingbai stoneware sherds discovered in the Minab area, southern Iran, from the Williamson Collection (photograph by Lin Meicun).

Figure 6. Dehua Qingbai stonewares from the thirteenth-century Java shipwreck, from the collections in the Field Museum, Chicago (photograph by Lin Meicun).

The distribution of Marco Polo type/Dehua Qingbai wares across the Indian Ocean is mainly in the Malacca area, southern India, the Persian Gulf, and eastern Africa (Figure 7). In the eastern region of the Indian Ocean ‘Marco Polo wares’ have been mainly found around the Malacca area. For example, the Pengkalan Bujang port site in north-western Malaysia, which dates to the twelfth to thirteenth centuries, has yielded some creamy white and opaque glazed sherds decorated with thin lines in relief. These are also believed to have been produced in the Dehua kilns (Leong, Reference Leong1973: 216–19). Similar finds have been noted on sites in Kota Cina on the north-eastern coast of Sumatra, which date from the twelfth to early fourteenth centuries (McKinnon, Reference McKinnon1984), on Tioman Island, off the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia (Lam, Reference Lam1985), and on the Temasik sites in Singapore (Miksic, Reference Miksic1985, Reference Miksic, Miksic and Low Mei Gek2004). ‘Marco Polo wares’ from the Philippines are only found around Manila, which was probably the only major entrepôt for Chinese products in the thirteenth century (Fox, Reference Fox1967: 55).

Figure 7. Distribution of Dehua Qingbai wares across the Indian Ocean c. ad 1274–1350 (drawing by Ran Zhang).

In southern India. the sites at Periyapattinam, Palaya-Kayal, Motupalli, Kunnattur, Pondicherry (see Subbarayalu, Reference Subbarayalu, Prabha Ray and Salles1996; Karashima, Reference Karashima2004), and Pattanam (authors’ data), together with the site at Polonnaruwa in Sri Lanka (Prematilleke, Reference Prematilleke, Bandaranayake, Dewaraja, Silva and Wimalarante1990; Prickett-Fernando, Reference Prickett-Fernando and Ho1994; Karashima, Reference Karashima2004: 62–63), have produced a large number of sherds of Fujian local kiln-produced or Dehua kiln-produced white/bluish-white stoneware.

In the Gulf, site K103 in the Minab area and other sites along the southern Iranian coast have also yielded these classes of wares and ‘Marco Polo wares’ have also been recovered from the port of Qalhat in the east of Oman and the port of al-Nudud, as well as in Kush in the UAE (Morgan, Reference Morgan1991: 70–71; Kennet, Reference Kennet2004: 48–49; Priestman, Reference Priestman2005: 294–95; Scalet, Reference Scalet2016: 24). Only a limited number of reports of similar findings have been noted in Yemen and the Red Sea: al-Shihr has yielded so-called fine Dehua sherds, and a few sherds of Dehua Qingbai stoneware have been reported from the site in Quseir in Egypt (Whitcomb, Reference Whitcomb1983; Hardy-Guilbert & Rougeulle, Reference Hardy-Guilbert and Rougeulle1997; Hardy-Guilbert, Reference Hardy-Guilbert2001, Reference Hardy-Guilbert2005). But it appears that no finds of Dehua Qingbai stonewares have been reported in Fustat, even though it is an important site in northern Egypt (Ma & Meng, Reference Ma and Meng1987: 4–5; Yuba, Reference Yuba2014). In East Africa, a limited number of ‘Marco Polo type’ wares have been discovered at the sites of Kilwa (Chittick & Wheeler, Reference Chittick and Wheeler1974), Shanga (Horton et al., Reference Horton, Brown and Mudida1996), Mahilaka in Madagascar (Radimilahy, Reference Radimilahy1998: 180), and Gedi (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Qin and Kiriama2012).

Discussion: How Strong is the Association of the Dehua Porcelain Wares with Marco Polo?

Using the evidence described above, the following section aims to further explore the association of Dehua porcelain wares with Marco Polo. It will be seen that the so-called ‘Marco Polo jar’ and wares are contemporary with Marco Polo and his return journey from China back to the West.

Dating the ‘Marco Polo jar’ and the Dehua Qingbai wares

As mentioned, two possible dates, ad 1307 and 1367, feature on the clay boxes bearing a cyclical date of ‘dingwei (丁未)’ unearthed at Qudougong, and these two dates remain open to debate by scholars (Fujiansheng Bowuguan, 1990: 140–42; Lin & Zhang, Reference Lin and Zhang1992: 565; Ho, Reference Ho and Schottenhammer2001: 251). The second date was proposed by Ho Chuimei (Reference Ho and Schottenhammer2001: 251), who suggests that this later date is highly probable. Ho links some white stonewares, also from Qudougong, to wares that were found in association with Yuan blue and white porcelain in burials in the Philippines. Given that no mature blue and white porcelain was made before the early fourteenth century (around the 1330s) (Zhongguo Guisuanyan Xuehui, 1982: 339–42), the production of white stonewares at Qudougong could have lasted into the late fourteenth century, and Ho therefore argues that ad 1367 is the likely date (Ho, Reference Ho and Schottenhammer2001: 251).

On the basis of the distribution pattern presented in the previous section, another observation, however, counters Ho's argument, and links it more directly to Dehua Qingbai wares. In the Gulf, the distribution of Dehua Qingbai wares in the Minab area of southern Iran has no association with blue and white porcelain, while many blue and white porcelain sherds but no finds of Dehua Qingbai wares have been discovered on the island of Hormuz (see Morgan, Reference Morgan1991; Priestman, Reference Priestman2005). The Kingdom of Ormus re-settled Hormuz Island from Minab in ad 1325 (Aubin, Reference Aubin1953: 102; Piacentini, Reference Piacentini1992: 171–73); it therefore seems that the absence of Dehua wares from Hormuz Island would argue against the later date of the ‘dingwei’ clay boxes. A similar situation was observed at Fustat, where Dehua Qingbai wares do not occur but many blue and white porcelains do (Ma & Meng, Reference Ma and Meng1987: 4–5; Yuba, Reference Yuba2014). Similarly, the cargo found in the Sinan shipwreck off the coast of Korea contained some Dehua Qingbai wares but no mature blue and white porcelains, and this can be dated to ad 1323 (Shen, Reference Shen2012: 18, 212–13). On this basis, the ‘dingwei’ clay boxes date to ad 1307, and the dating of Dehua Qingbai wares of the ‘Marco Polo type’ should be dated from the late thirteenth to the early fourteenth century. It therefore appears that the date range of Dehua Qingbai wares produced at the Qudougong kiln site can be been narrowed down to match the era of Marco Polo's travel to China.

Longquan celadon pottery versus ‘Marco Polo wares’

When taking a general view of the Chinese ceramic trade during the Yuan dynasty, it should be noted that Longquan celadon pottery, the type which dates to the late thirteenth to fourteenth centuries, has been found in vast quantities across the Indian Ocean (Morgan, Reference Morgan1991; Zhang, Reference Zhang2016: 281–85) (Figure 8). It has even been reported that, on rare occasions, the Longquan celadon reached Venice at that time (Ye, Reference Ye2000: 12). Celadon pottery was also being produced on a huge scale in the Longquan County of the Lishui City prefecture (丽水市) in southern China, although the latter was named Chuzhou during the Yuan dynasty. Archaeologically, approximately 445 individual ceramic kiln-workshops have been reported in Longquan and these can be dated to no later than the early fourteenth century (Qin & Liu, Reference Qin and Liu2012: 10).

Figure 8. Yuan Chinese Longquan celadon finds from southern Iran, from the Williamson Collections. 1–2) Longquan celadon small jars; 3) Longquan celadon bowl. © Jeff Veitch. Reproduced by permission of Jeff Veitch.

The production of celadon ceramic in Longquan County and its consumption across the Indian Ocean was on a much larger scale than that of Dehua Qingbai wares, yet there is not a single word about it in Marco Polo's account. He only very briefly mentions Lishui (Chuzhou); ‘…at the end of this three-day journey lies the city of Chuzhou (Cugui/Guiguy), which is very big and beautiful…’ (Cliff, Reference Cliff2015: 215). Thus it appears that Marco Polo did not notice that there was a large ceramic industry based around Chuzhou, namely within Longquan County. This could be merely due to the fact that he was not focused on ceramic industries. Or it may be that, because the period of great prosperity of the celadon industry in Longquan County was during the middle to late period of the Yuan Dynasty (Qin & Liu, Reference Qin and Liu2012: 10), the industry grew after the time of Marco Polo's visit, and may not have been sufficiently developed to attract his attention.

Marco Polo's return route from China to Europe

It is reasonable to suggest that Marco Polo's return journey included three important stops: i.e. Malacca, Mabar, and Hormuz. Along with the maritime voyage from China to the West, the first stop, Malacca, cannot be omitted for geographical reasons. As for southern India and the Persian Gulf, they were very well recorded by Marco Polo.

Marco Polo claims that his return voyage from China was with an embassy that was taking a bride from the Mongol Royal House to marry her cousin, the Ilkhan of Persia, and this royal marriage has been recorded in both Chinese and Persian sources (Cleaves, Reference Cleaves1976). However, there is no direct historical evidence to demonstrate that Marco Polo left China and travelled with these ambassadors, as there is no note of the name of Marco Polo. But Marco Polo clearly mentions the names of the ambassadors he travelled with as Oulatai, Apousca, and Coja, and this could indicate that he did return from China with the embassy (De Rachewiltz, Reference De Rachewiltz1997: 47–53). These names were recorded by Yongle Dadian (永乐大典Yongle Encyclopaedia) (Yang & Ho, Reference Yang and Ho1945; Cleaves, Reference Cleaves1976). It seems that this not only reports that Marco Polo left China sometime in late ad 1290 or the very beginning of ad 1291, but it also gives the voyage's final destination, Mabar (Pandya dynasty) in southern India. After his visit to Mabar, Marco Polo claimed he voyaged to the entrance of the Persian Gulf, where he visited Old Hormuz, the Minab area in southern Iran, in ad 1294/1295. He states that this is a regional capital but without describing the fortifications, which were attacked by the son of the ruler of Kish in the 1310s. Ibn Battuta provides descriptions, dating from ad 1329 and 1347, of two places called Hormuz: one on the mainland and another on an island, Hormuz Island (Morgan, Reference Morgan1991: 71, 78). Marco Polo's claims that during his visit to the southern part of the Persian Gulf he saw ‘many heavily laden ships arrive [at Qalhat] from India. They find a ready market for their wares, because from here the spices and other goods are carried to many cities and towns in the interior…’ (Cliff, Reference Cliff2015: 300).

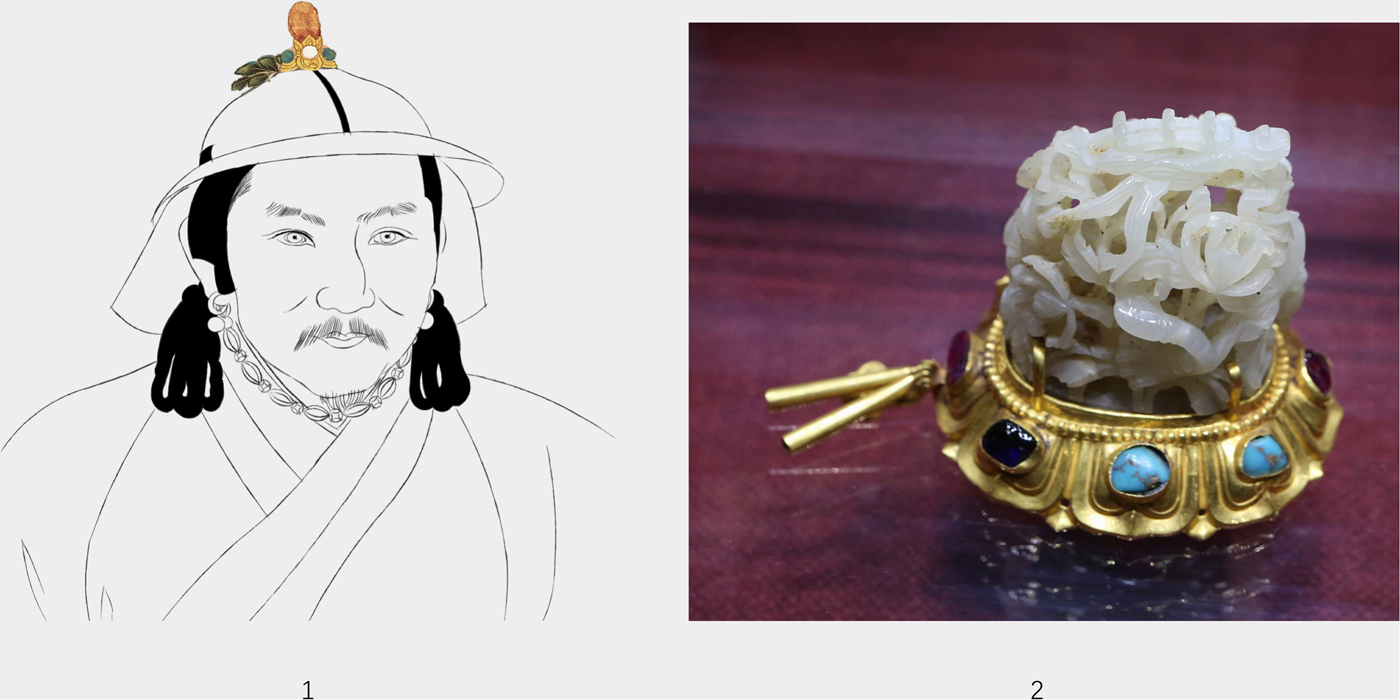

Marco Polo's return sea voyage to Europe was probably along one of the regular trade routes from China to the West across the Indian Ocean. This is because, historically, knowledge of Mabar was well recorded in Chinese Yuan history, and diplomatic relations were established between Yuan China and Mabar in ad 1281 (Song, Reference Song1984: the Countries of Mabar, 4669–70). The Mabar's tribute trade and its commodities have been listed in detail in a book entitled Jie Xing Yu (解醒语) (Ma, Reference Ma2005: 21). Moreover, archaeological evidence shows that the Chinese ceramic trade was first introduced to southern India on a large scale (Zhang, Reference Zhang2016: 281–85). In addition, some jewellery and gemstones from southern India have been discovered in China, including some Mongolian-style hat ornaments which were found in the Ming (ad 1368–1644) mausoleum of the King of Liang Zhuang in Hubei province (Liang, Reference Liang2003). These finds are identical to those shown in the Yuan Mongolian Khan's portrait (Figure 9), and can be considered part of the war trophies of the Chinese Ming armies when they re-took the throne from the Yuan Mongolian empire. These items of jewellery and gemstones were given to members of the Ming royal family. Finally, an examination of the distribution map of ‘Marco Polo wares’ shows that these three locations (Malacca, southern India, and the Persian Gulf) have separately yielded a large number of Dehua Qingbai wares, thereby signifying that Chinese ceramic productions were traded in the Indian Ocean along this regular maritime route.

Figure 9. Re-drawing of a portrait of the Mongolian Khan, Emperor Wen-zong, with a hat ornament (1), and Mongolian-style hat ornaments discovered in the mausoleum of King Liang Zhuang (2) (re-drawn by Ran Zhang, after Shi & Ge, Reference Shi and Ge2002: 28; photography by Jian Liang). Photograph © Jian Liang. Reproduced by permission of Jian Liang.

Conclusions

The association of the Qingbai porcelain jar housed in the Treasury of San Marco in Venice with Marco Polo was originally made by Oscar Raphael (Raphael, Reference Raphael1932), but it has been widely accepted by many archaeologists without further analysis. This article presents the archaeological evidence on the production and consumption patterns of the Dehua Qingbai porcelain wares that can be dated to the time of Marco Polo. It emerges that the so-called ‘Marco Polo jar’ and ‘Marco Polo wares’ are not only dated to the period when Marco Polo visited China, but also that their provenance matches the city where these wares were manufactured, which Marco Polo visited. The claims about the Dehua ceramic industry made by Marco Polo are reasonable and reliable, although he might not have been particularly interested in Chinese ceramics, because he obviously missed the Longquan celadon industry in Chuzhou which he claims to have passed through. Moreover, the archaeological evidence presented here indicates that Marco Polo travelled back to Venice along the route via which ‘Marco Polo wares’ were traded. He could have therefore acquired the Chinese Qingbai porcelain jar in Dehua city in southern China, or on his journey home.

Behind Marco Polo, there must have certainly been other merchants from Europe, the Persian Gulf, and India who travelled and traded with China; yet Marco Polo's stories are the only historical account that indicate that European merchants could travel to China by both land and sea routes at this time. The ‘Marco Polo jar’, namely an item of Dehua Qingbai ware, is also the only archaeological evidence that could be linked to Marco Polo, indicating that the European merchants were trading with China in the early fourteenth century. The archaeological finds of Dehua wares presented in this study demonstrate the economic boom in the Indian Ocean trade between China and the West during the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to the Williamson Collection Project run by Dr Derek Kennet (Department of Archaeology, Durham University), to Professor Robert Layton (Department of Anthropology, Durham University), and Professor Robin Skeates (EJA) for support and suggestions.