Introduction

When facing hard cases, especially in human rights disputes, courts are not able to rely on standard interpretative methods. Consequently, courts often tend to use abstract principles and values as second-order justification instruments. Footnote 1 The problem with applying abstract values and principles as legal arguments is that they are often understood and interpreted differently by judges and legal scholars in different countries.

Imagine, for example, if particle physicists examined an interaction of the same elementary particles in a hundred different laboratories and produced a hundred different results. Even though they would be able to describe each of the hundred interactions in detail, they would not be able to say anything general about the interaction of these particles, and consequently, be unable to predict the behaviour of these elementary particles beyond their laboratories. This would be a great inconvenience. Although this problem is unlikely to occur in particle physics research, it occurs frequently in social sciences, the nature of the studied objects in these research fields being determined strongly by culture and history, etc. A research approach which does not reach beyond its cultural and historical context and prevents any results from being generalised across various countries or cultures is generally characterised as extremely relativistic in cross-cultural research. Footnote 2 Unfortunately, almost without exception, an extremely relativistic approach is also applied in the analysis of abstract values in legal argumentation.

The present article focuses specifically on human dignity, a construct where an extremely relativistic approach has already led to noticeable and unwanted consequences and been the topic of frequent discussion. Footnote 3 Indeed, an enormous quantity of literature has been published concerning human dignity in constitutional and international law. Footnote 4 Much of it, however, has focused predominantly on the substantive meanings of the concept in various countries and therefore adopted an extremely relativistic view. Consequently, a clear idea can be formed of the varied interpretations of dignity by the courts. Footnote 5 Some of the most frequently applied substantive meanings of human dignity refer to the prohibition of treating humans as mere objects of state power, Footnote 6 the prohibition of torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Footnote 7 the right to personal autonomy, Footnote 8 the right to life, Footnote 9 freedom of speech, Footnote 10 respect for one’s reputation, Footnote 11 the right to recognition and equal treatment (for both individuals and social groups), Footnote 12 the right to financially and materially sufficient life conditions, Footnote 13 and even the obligation to live and act in a dignified manner. Footnote 14

My objective, however, is to move beyond a description of these regional differences and similarities in the interpretation of human dignity and to adopt a more universalistic approach towards the construct. This would allow me to produce much more general results applicable to human dignity, regardless of the cultural and historical context of a country. To achieve this aim, I focus on human dignity from a functional perspective, where function refers to the role human dignity has in legal argumentation before the courts. The functional analysis therefore investigates questions that concern how different functions of human dignity impact legal reasoning rather than what human dignity substantively means. I applied a functional perspective because the functions of human dignity, in contrast to substantive content, are highly context-invariant and can thereby achieve construct equivalence across countries. Hence, I believe that the functional perspective is able to not only overcome the context-specific variances in the interpretation of human dignity, but also help reveal and solve several core issues of the concept which are shared across legal and cultural contexts and have hitherto been neglected in the literature.

It is worth noting that, to date, the number of articles which have presented an analysis of the functions of human dignity is few, Footnote 15 and none have provided a comprehensive theoretical and methodological framework to analyse dignitary argumentation exclusively from a functional perspective and enable a universalistic perspective. In the present article, I suggest such a theoretical framework and support it with a qualitative analysis of several rulings by supreme, constitutional, and international courts from around the world.

First, I use three variables (content width, argumentative power, and applicability before the courts) and an analysis of historical thought on human dignity to define its three basic functions in current legal argumentation (source of human rights, objective value, and relative individual right). Second, I explain how undesirable hybrid functions are created from basic functions and why they are problematic in terms of the rationality, soundness, and predictability of legal argumentation and the decisions based on it. Finally, I suggest a set of principles for minimising the emergence and adverse effects of hybrid functions of human dignity.

The three basic functions

To analyse from a functional perspective the issues in adjudicating human dignity, the first step is to define the basic functions of human dignity. I do so through three analytical criteria (variables): (a) content width (i.e. how limited is the scope of the substantive meaning of dignity); (b) argumentative power (i.e. where dignity is placed in the hierarchy of human rights law and how much it can be limited); (c) applicability before the courts (i.e. whether and how dignity can be used as a legal argument in specific cases before the courts). Each of these variables holds three values (strong, medium, and weak) according to whether they strengthen or limit the particular function of human dignity in comparison to other functionsFootnote 16 Each function can, therefore, be described as a combination of these three variables (or characteristic features).

To match the specific value of each variable to a particular basic function of human dignity, I analysed the historical views on human dignity and separated them into three eras, namely the era of ancient dignitas, the era of iusnaturalistic inherent human dignity, and the era of achieving dignified life. I argue that each of these eras has left its traces in current legal systems, since each corresponds to one of the three distinctive basic functions of human dignity in legal argumentation, interpretation, and adjudication today (i.e. relative individual right, source of human rights, and objective value). Footnote 17

Relative individual right

The first step of the historical analysis examines the context of ancient Greece and Rome, where dignity (or dignitas) was understood as a level of acquired (or attributed) social status and reputation. Footnote 18 In modern words, dignitas refers to an individual human right protecting one’s level of social status in society earned throughout life. Footnote 19 Dignitas was not distributed equally across society: the level of dignity was determined by the previous actions and behaviour of the citizen. Only the right to protection of the acquired level of dignity against unlawful encroachment was truly equal. Footnote 20

Understanding dignity as dignitas resembles the first and the simplest function of human dignity in modern human rights law, namely the relative individual right,Footnote 21 which seeks to protect one’s already acquired reputation Footnote 22 and honour Footnote 23 (i.e. dignity as opposed to shame). Footnote 24 I linked human dignity as a relative individual right to the following characteristic features. A clear benefit is that, as an individual right, it can be applied directly in individual cases (i.e. strong applicability before the courts). However, it also has clear substantive content and meaning and should not, therefore, be interpreted extensively or interchangeably with other distinct individual rights (i.e. weak content width). Furthermore, as a relative right (as opposed to absolute rights), human dignity cannot be granted any privileged position among other rights and may therefore be proportionally weighed against and potentially also outweighed and limited by these rights in individual cases (i.e. weak argumentative power).

A good example of the proper use of human dignity as a relative individual right is found in the judgment of the Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic Footnote 25 concerning a dispute between former Czech pop star, Helena Vondráčková, and a music critic, Jan Rejžek. In Vondráčková’s opinion, Rejžek violated her dignity by publishing an article which criticised her past as tainted by cooperation with the former communist regime. The Court had to resolve the conflict of the individual right to human dignity understood under the Czech Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms as the right to protect one’s reputation and honour Footnote 26 and the individual right to freedom of speech. Footnote 27 The Court weighed each right proportionally to the other and decided, in this case, in favour of freedom of speech over the right to dignity.

Source of human rights

The second historical understanding of human dignity is first observable in the thoughts of Cicero, who understood it as a natural feature of every human being regardless of social status or earnings. According to Cicero, human dignity is the feature which distinguishes humans from animals. Footnote 28 An understanding of human dignity such as this was expanded by Christian philosophers. Aquinas, for instance, claimed that every human is born with inherent human dignity emanating from the similarity of human beings to God (imaginatio dei). Footnote 29 Human dignity should, therefore, be understood as a universal and inherent feature granted to humans equally, solely because they are human. This understanding was also adopted by Pico della Mirandola, who argued that all creatures apart from humans are determined by the law of nature. Only human beings are granted the free will to determine their nature, which gives rise to their dignity. Footnote 30 Centuries later, Kant separated Footnote 31 the concept of natural human dignity from theology and highlighted reason and autonomous will as sufficient criteria for intrinsic human dignity. According to Kant, a rational being with an autonomous will disposes of the ability to discover moral laws and transforms them into moral maxims to guide its thoughts and behaviour. Such an autonomous and rational being is consequently an end in itself, and therefore cannot be instrumentalised or objectivised. Hence, all human beings are granted inherent, intrinsic, and equal dignity. Footnote 32

Dignity as an inherent human feature resembles the second function of human dignity in contemporary human rights law, namely the source of human rights. Footnote 33 As with the first function, I linked human dignity as a source of human rights to the following characteristic features. In this case, the function of dignity is limitless in terms of its substantive content because it is a source of all individual rights (i.e. strong content width). Footnote 34 An example of this concept is found in the judgment of the Supreme Court of Canada: the Court stated that ‘The idea of human dignity finds expression in almost every right and freedom guaranteed in the Charter [i.e. The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms]’. Footnote 35

Human dignity as a source of human rights also sits at the top of the human rights system. It cannot be weighed against any value or right or be limited by them (i.e. strong argumentative power). This perspective is found in several judgments of the German Federal Constitutional Court, which understands human dignity as the ‘highest legal value’ Footnote 36 or ‘fundamental principle and highest value’, Footnote 37 signalling its superior status under German constitutional law. Footnote 38

However, I argue that the use of this function of dignity in adjudication requires significant restriction (i.e. weak applicability before courts). It should serve as an interpretative framework for legal argumentation rather than the legal argument itself (i.e. the binding legal rule applied in a specific case or dispute). A good example of this perspective is found in a judgment of the European Court of Human Rights, in which the Grand Chamber stated:

Respect for human dignity forms part of the very essence of the Convention (…). The object and purpose of the Convention as an instrument for the protection of individual human beings require that its provisions be interpreted and applied so as to make its safeguards practical and effective. Any interpretation of the rights and freedoms guaranteed has to be consistent with the general spirit of the Convention (…). Footnote 39

Two important reasons for this restriction exist. First, as a source of all human rights, human dignity does not have any specific legal normative content since it hypothetically refers to any individual right. Therefore, it does not carry any specific legal rule which could be applied as a legal argument before a court. Hence, I consider the use of terms such as ‘mother right’ Footnote 40 or the ‘right to have rights’ Footnote 41 unfortunate, as they suggest that human dignity as a source of human rights is in fact an individual right with specific substantive content.

Second, human dignity is the source of all human rights. Consequently, any conflict of human rights would be unsolvable, because human dignity, if directly applicable, would be associated with every conflicting human right and render them all absolute (i.e. resistant to any weighing or limitation since all of them would be considered vital components of inviolable human dignity). Such a situation would lead to either the inability of the court to resolve the dispute or an arbitrary decision of the court claiming that the inherent dignity associated with one of the conflicting human rights is actually not absolute nor inviolable and can be limited, which is impossible, because dignity cannot be simultaneously inviolable and violable. Footnote 42 In other words, any attempt to directly apply human dignity understood as a source of human rights to a specific case would necessarily lead to an illogical and unsolvable situation which endangers the legitimate expectations and legal certainty of the disputing parties before the court.

Objective value

The third historical view of human dignity emerged in the nineteenth century, mainly under the influence of socialist ideology and continental republicanism. In this case, dignity is understood as a societal objective to be achieved rather than an inherent feature in humans. This objective can be described as a dignified life or the dignified being Footnote 43 of a person in society and can be achieved when a person is granted a sufficient standard of living (i.e. when their civil, political, social, and other rights are granted and protected to a sufficient level by the state). Footnote 44 This approach to dignity is therefore strongly normative, as it presents a desirable state of human life which should be sought by society and which can be demanded by its citizens. Footnote 45 The content of dignity as an objective of human life is partially inspired by the ancient dignitas, which also refers to dignified living within a society. However, dignity as an inherent human feature influenced this third view through its universal character, as a dignified life should be obtainable by all people. Linking these two former (and to some extent contradictory) approaches, this third approach states that every human has the right to ‘dignities’ which have hitherto belonged solely to the nobility. Footnote 46 The most important and distinct feature of this third view of dignity lies in its objectivity. Dignity is not an inherent feature of humans but an objective condition of their lives, a real goal to be achieved rather than an abstract thought.

Similarly to the aforementioned historical views, dignity as an objective condition of human life corresponds to a specific function of dignity in current human rights law, namely dignity as an objective value obtainable through the recognition and protection of human rights. Again, I linked this function of dignity to the following characteristic features. Dignity as an objective value is hierarchically situated between individual rights and the ultimate source of all human rights. As a value, human dignity lies above individual human rights and cannot be outweighed solely by these rights because it gives them the final purpose (objective) of their existence. Dignity can, however, be outweighed and limited by other values which stand at the same level, Footnote 47 such as justice, liberty, or equality (i.e. medium argumentative power). Footnote 48

Good examples of the use of human dignity as an objective value are scarce, since it is often combined with one of the other functions. However, one particular judgment of the Constitutional Court of South Africa Footnote 49 can demonstrate it. Even though the Court tended to (rather unfortunately; see the following section) combine all the functions of human dignity at a general level, Footnote 50 it was able to specify its function in this particular case and use it as an objective value, stating that

When the rights to life, dignity and equality are implicated in cases dealing with socio-economic rights, they have to be taken into account along with the availability of human and financial resources in determining whether the state has complied with the constitutional standard of reasonableness. Footnote 51

and that

A society must seek to ensure that the basic necessities of life are accessible to all if it is to be a society in which human dignity, freedom and equality are foundational. Footnote 52

Human dignity here is understood as an end to be (alongside other values) achieved by protecting individual (in this case, socio-economic) rights. It is not, however, claimed as absolute since it needs to be weighed proportionally against the availability of human and financial resources.

Objective values, including dignity, can be applied in legal argumentation, but only indirectly. They emanate as legal arguments into specific cases through a selected set of individual rights, especially in cases where more than one individual right from the selected set is at stakeFootnote 53 (i.e. medium applicability before the courts). Footnote 54 The logic here is that each objective value is achieved (realised) through a set of individual rights associated with it, giving those rights the final purpose (or objective) of their existence.

Direct applicability of human dignity as an objective value means that it would directly face the individual rights conflicting with it. This would result in a hierarchically uneven conflict between individual rights and the final purpose of the existence of (other) individual rights. A conflict such as this can be resolved in only two possible ways: (i) human dignity a priori wins the conflict, violating several due process rights of the disputing parties; (ii) or human dignity (i.e. the objective value) loses the conflict with individual rights, rendering the mere existence of objective values in the legal argumentation completely pointless.

Another issue arises when we ask precisely which individual rights are associated with human dignity as an objective value. Multiple answers based on the specific social, philosophical, or even ideological background are possible. A socialist (or in a wider sense, left-wing) ideology might associate a dignified life with social rights. Footnote 55 A liberal approach would prefer an association with personal autonomy and individual freedoms. Footnote 56 A conservative doctrine might associate a dignified life with rights to personal respect and reputation and possibly even with a duty to live in a dignified (decent) manner. Footnote 57 The final characteristic feature of human dignity as an objective value is, therefore, that the value of dignity can mean any individual right, Footnote 58 although, contrary to dignity as a source of human rights, not all individual rights concurrently (i.e. medium content width). Footnote 59 The set of rights associated with the value of dignity must be selected before it commences its role in legal reasoning as a legal argument, otherwise, when applied in individual cases, the aforementioned problems typical for human dignity as a source of human rights would emerge.

Again the decision of the Constitutional Court of South Africa provides a good example of this feature: the Court ruled that ‘there can be no doubt that human dignity, freedom and equality, the foundational values of our society, are denied those who have no food, clothing or shelter’. Footnote 60 According to the Court, the right to adequate housing

is entrenched because we value human beings and want to ensure that they are afforded their basic human needs. A society must seek to ensure that the basic necessities of life are provided to all if it is to be a society based on human dignity, freedom and equality. Footnote 61

In other words, the Court understands social rights as instruments to achieve the aforementioned objective values. These values therefore give purpose to (and justification for) the existence and protection of (in this case) social rights. Footnote 62

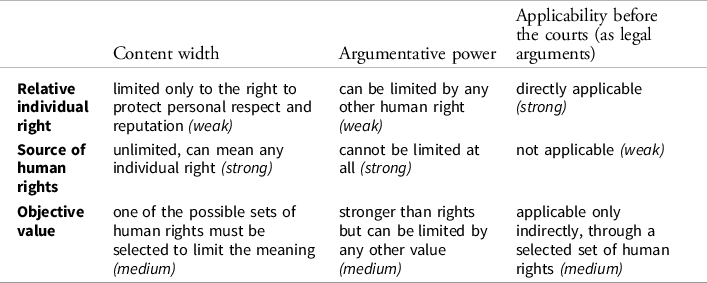

In summary, the three basic functions of human dignity described according to the three analytical criteria (variables) are outlined in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Basic functions of human dignity

Any of the three basic functions of human dignity can be legitimately used by the courtsFootnote 63 if the restrictions for each function are respected. The analytical criteria assist in not only defining each of the three functions but also, more importantly, in clearly distinguishing these functions from each other by identifying and balancing their strong, medium, and weak characteristic features.

Hybrid functions

Having described the basic functions of human dignity, I now introduce the hybrid functions and discuss what they are, how they emerge and work, and why I consider their use in legal argumentation problematic and potentially dangerous. First, I explain how the hybrid functions are created by combining the medium or strong characteristic features of more than one basic function. Second, I describe how their hybrid nature transforms these functions into axiomatic arguments which are based on presuppositions of an a priori greater importance of human dignity over other individual rights or objective values. Finally, I argue that both types of hybrid function (i.e. strengthened and absolute functions, and broadened and empty functions) are illegitimate argumentative fouls through their axiomatic nature and ought to be avoided in legal argumentation.

Derivation from the basic functions

Continuing with the analytical framework, I argue that hybrid functions are legal arguments which emerge when characteristic features of more than one basic function are combined. These functions can be derived from the basic functions according to the two conditions described below.

First, because the hybrid functions are meant to serve as legal arguments in individual cases, they must be applicable as arguments before the courts. Therefore, when the variable of applicability before the courts is applied, only two options (i.e. strong and medium) are possible. Let us label each hybrid function of human dignity which is directly applicable before a court (strong feature) as an individual right (since it is derived from the basic function of relative individual right), complemented by adjectives to describe other characteristic features. Similarly, let us label each hybrid function which is applicable only indirectly through a selected set of human rights (medium feature) as a value (since it is derived from the function of objective value), again complemented by various adjectives.

Second, let us assume that the purpose of using the hybrid functions is to strengthen the argumentation, not weaken it. Hence, we can claim that each hybrid function has at least one of the two remaining characteristic features (i.e. content width or argumentative power) which is elevated over the basic function from which it is derived. By derivation, I mean selecting a basic function which satisfies the first condition (i.e. relative individual right or objective value) and elevating at least one of its remaining two characteristic features to a higher level.

When the content width is changed from weak to medium, I use the adjective ‘broadened’ to indicate that dignity can have more meanings than only the right to protect one’s reputation. In the case of changing the content width from weak or medium to strong, I use the term ‘empty’ to indicate that dignity can be described as an empty shell Footnote 64 which can be filled with any content and consequently refer to any individual right or any objective value.

If the argumentative power is elevated from weak to medium, I use the adjective ‘strengthened’ to highlight that dignity is hierarchically elevated and cannot be further limited or outweighed by other individual rights. Finally, I use the word ‘absolute’ to describe when the argumentative power of dignity is elevated from weak or medium to strong, signalling that dignity cannot be limited at all.

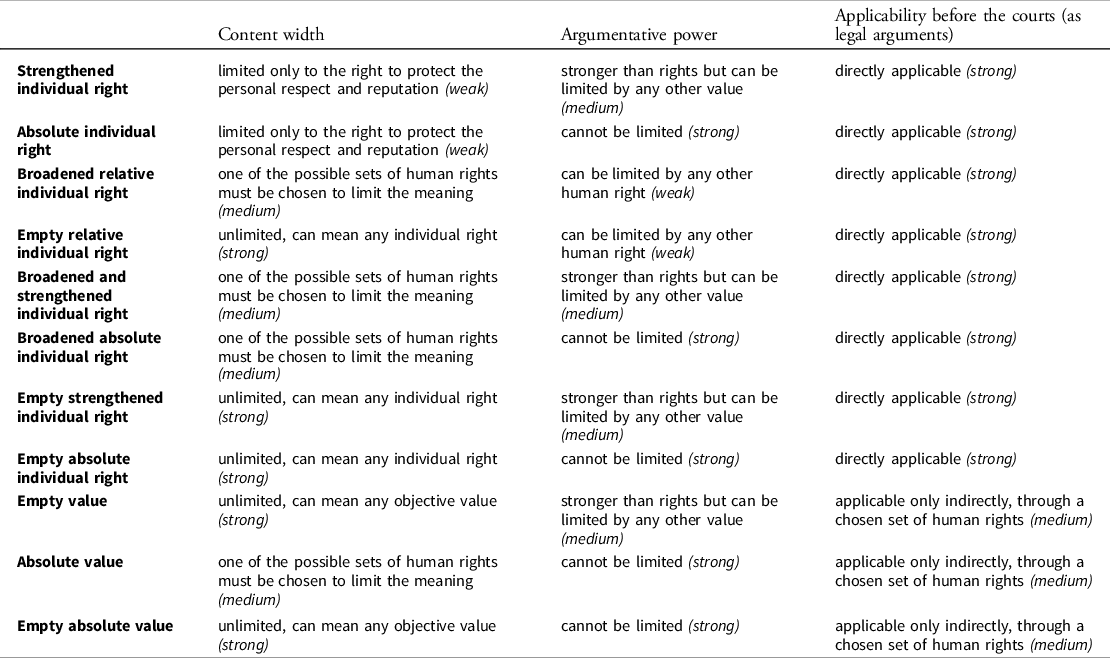

Applying these conditions, eleven distinct hybrid functions of human dignity can be theoretically derived. These are listed below in Table 2.

Table 2. Hybrid functions of human dignity

It is worth noting that not all of these theoretically predicted hybrid functions of human dignity can be observed in the legal argumentation before the courts or by the courts. The theory, however, would not be complete without mentioning them all since they share the same logical and argumentative problems.

The axiomatic nature of hybrid functions

The second aim of this section brings me to an explanation of how and why I believe the use of hybrid functions in legal argumentation is problematic. The following general (yet crucial) statement, which will be analysed and explained later, establishes the argument: Ignoring the limitations given by the weak (or medium) characteristic features of the three basic functions of human dignity gives rise to new hybrid functions which combine the strong (or medium) features of more than one basic function. These hybrid functions of human dignity consequently tend to behave axiomatically or lead to logically unresolvable situations, which in turn must again be overcome through axioms. Footnote 65

By axiom, I refer to an assumption which can neither be proved nor disproved and which serves as a basis from which logical consequences can be drawn. Footnote 66 Even though axioms are irreplaceable in scientific theories, their use in argumentation (and especially legal argumentation) is deeply problematic. This is because an axiom, once accepted by the court as an argument, can neither be disproved nor outweighed in any manner, Footnote 67 leaving the argumentation against itself impossible and the disputing party toothless.

The examples below demonstrate that if legal argumentation begins with an axiom, it inevitably leads to an outcome (i.e. decision) which is the logical consequence of that axiom. As a result, any counter-arguments conflicting with the initially accepted axiom are a priori rejected as irrelevant since the already accepted axiom and its consequences cannot be ignored or limited from the perspective of formal logic. Footnote 68 Hence, I argue that the use of axioms in legal argumentation is an illegitimate argumentative foul which: (a) deprives the disputing parties of some of their due process rights; (b) reduces the quality and persuasiveness of legal reasoning; (c) tends to transform any legal conflict into a dignitary one; (d) prevents proper use of proportionality and weighing instruments; and (e) can violate the principles of legitimate expectations and legal certainty.

These initial thoughts are explained in more detail and demonstrated through examples in the following two subsections, which present an analysis of the problems caused by a) strengthened and absolute hybrid functions which possess a higher level of argumentative power than the original basic function from which they were derived and b) broadened and empty hybrid functions of human dignity whose content width are boosted.

Problems of strengthened and absolute functions

Any strengthened or absolute function of human dignity can be understood as a hybrid function since it behaves in legal argumentation as either a relative individual right and concurrently an objective value or source of human rights which cannot be limited or outweighed by other individual rights respectively cannot be limited at all, or an objective value and concurrently a source of all human rights which cannot be limited at all. This hybrid nature makes the strengthened and absolute functions of human dignity inherently axiomatic and means that these functions, once used by a court as legal arguments, are in fact assumptions which cannot be proved or disproved and thereby determine the outcome of the entire dispute.

In the case of a conflict at the level of individual rights, a court assumes that, compared to other rights, human dignity is a priori (automatically) a more important individual right because it is not only a right but concurrently an objective value or even a source of all human rights, and therefore it must have priority over any possible conflicting relative individual rights (i.e. to be incommensurable with them). Footnote 69

In the same manner, in the case of a conflict at the level of objective values, a court assumes that human dignity is a more important objective value (i.e. a value of a higher order) Footnote 70 because it is not only a value but concurrently a source of the entire human rights system, and therefore it is given priority over any possible conflicting objective values. Moreover, the absolutisation of dignity as an objective value also leads to the absolutisation of any selected set of rights associated with it, preventing other rights (i.e. those not included in the protected set) from any chance of outweighing the ‘rights linked to dignity’. Footnote 71 Since dignity as an objective value can be associated with different sets of human rights in different disputes, a court could potentially pick and absolutise any set of human rights and end the dispute before it even begins or before any argumentation by a disputing party is presented.

Two good examples can be analysed more deeply to demonstrate this issue. First, let us examine the Luftsicherheitsgesetz decision of the German Federal Constitutional Court, concerning the constitutionality of shooting down an aircraft which is hijacked for use against human lives. Footnote 72 The Basic Law of Germany states that ‘Human dignity shall be inviolable. To respect and protect it shall be the duty of all state authority’. Footnote 73 Human dignity is therefore understood as absolute (inviolable), even though the substantive meaning of this concept is unclear, leaving a broad space for judicial interpretation. Footnote 74 In this particular case, the Court applied a purely Kantian interpretation, stating that dignity requires human beings not to be treated as mere objects of state power or action. Footnote 75 The Court also associated dignity with the right to life, stating that ‘Human life is the vital basis of human dignity’. Footnote 76 This association led the Court to the argument that the passengers in a civil aircraft hijacked by people who want to abuse them by using them as weapons in a targeted crash are (in the case of shooting down) treated by the state as ‘mere objects of its rescue operation for the protection of others’. Footnote 77 Consequently, ‘Such a treatment ignores the status of the persons affected as subjects endowed with dignity and inalienable rights’. Footnote 78

The second example is the decision by the European Court of Human Rights in the case of Al Nashiri v Poland. Footnote 79 Contrary to the Basic Law of Germany, the European Convention on Human Rights, with one exception, Footnote 80 does not contain a reference to human dignity. Yet two of the arguments the Court used to decide on the matter were based on the concept of dignity. Referring to the famous decision in the case of Pretty v United Kingdom, Footnote 81 the Court again expressed the idea that ‘the very essence of the Convention is respect for human dignity and human freedom’. Footnote 82 The original decision in Pretty v United Kingdom linked dignity to two specific rights protected by the Convention, namely the prohibition of torture Footnote 83 and the right to respect for private and family life. Footnote 84

Both rights had a significant role in Al Nashiri v Poland, and both were considered absolute by the Court. The reasons for their absolutisation, however, were different. The absolute nature of the prohibition of torture is explained by the fact that ‘unlike most of the substantive clauses of the Convention, Article 3 makes no provision for exceptions and no derogation from it is permissible under Article 15 § 2 even in time of war or other public emergency threatening the life of the nation’. Footnote 85 This is a usual Footnote 86 and legitimate systematic interpretation which does not necessarily need to use a hybrid function of human dignity to be valid. In contrast to Article 3, Article 8 is absolutised purely as a consequence of using the hybrid function of human dignity. After claiming that dignity is the essence of the Convention (even though it is not mentioned in the Convention itself), the Court argued that various aspects (e.g. the right to personal development, the right to establish and develop relationships with other human beings, and the mutual enjoyment by members of a family of each other’s company) of the right to private and family life were violated, and consequently ‘the interference with the applicant’s right to respect for his private and family life must be regarded as not “in accordance with the law” and as inherently lacking any conceivable justification under paragraph 2 of that Article’. Footnote 87

Both examples are clear cases of using hybrid functions of human dignity as axioms, the consequences being those introduced in the previous subsection. In the former case, the Court argued that since (absolute) human dignity is at stake, no counter-arguments (such as the lives of the thousands of people who could have potentially died if the terrorists had succeeded and the civil aircraft under their command had indeed crashed) could be taken into account and shooting down the aircraft is (always and under any circumstances) therefore unconstitutional. Footnote 88 In the latter case, the Court concluded that because the right to privacy and family life is linked to human dignity (the very essence of the Convention), it cannot be limited, since any limitation inherently lacks any justification, even though Article 8 paragraph 2 states otherwise. Again, any counterarguments (in this case, for example, the opportunity to gain information about potential future terrorist attacks which could save innocent lives) are a priori invalid.

The purpose of this analysis is not to argue that the state must be allowed to shoot down aircraft or torture terrorists for information. The aim is to show that these issues were not solved or reasoned by the courts in a logically sound or persuasive manner, as their reasoning contained axiomatic arguments.

As we saw in the examples, the assumption (axiom) of the greater importance of human dignity, once accepted, cannot be disproved or argumentatively overcome. Consequently, the proportionality test or any other type of test based on weighing the entities of equal argumentative power against each other in individual cases cannot be conducted correctly, as one of the weighted entities is strengthened or even absolute and therefore automatically prevails under any circumstances Footnote 89 (e.g. dignity as a prohibition of instrumentalisation of the people in an aircraft is always more important than the lives of the people on the ground, or dignity as a right to the privacy and family of the suspected terrorist is always more important than the lives of their potential victims).

In other words, when a strengthened or absolute hybrid function of human dignity enters the argumentative arena, it cannot lose and it decides the dispute before it even starts. It does so by transforming the argumentative arena into a dignitary one, where only dignitary arguments are relevant since the axiom that says dignitary argumentation is hierarchically superior to any other argumentation has already been accepted.

Such an approach, however, is an irreconcilable contradiction to the common sense of justice and due process rights since it deprives the party to the dispute of the opportunity to defend and argue in its favour through any argument other than dignitary arguments. In addition, the reasoning of the court does not (or indeed is not even able to) properly and persuasively deal with the majority of potential counter-arguments, thereby reducing its legitimacy to those who did not identify themselves with the initial axiom. Moreover, since the court can (quite arbitrarily) accept or reject the axiom at the beginning of the reasoning, and since this acceptance or rejection determines all the outputs of such reasoning, the results of the dispute cannot be predicted. This approach is therefore also in direct contradiction to the principles of legitimate expectations and legal certainty since it cannot be foreseen whether and when the court will again use axiomatic dignitary argumentation.

Problems of broadened and empty functions

Following on from the above argument, the fact that only dignitary argumentation is relevant in the dignitary argumentative arena encourages both disputing parties and the court to translate all other arguments into dignitarian language. Each individual right or value must hide behind the veil of dignity for it to succeed in a dignitarian argumentative arena. Therefore, once the strengthened or absolute functions of dignity are used, we can expect that broadened or even empty functions emerge as an attempt by the other, ‘defending’ party to eliminate the unfair advantage of dignitarian arguments.

However, when a hybrid function of dignity possesses a higher level of content width than the original basic function from which it was derived (i.e. when it is broadened or empty), the second group of problems emerges. Footnote 90

Broadening the meaning of one of the original basic functions (i.e. relative individual right or objective value) is unnecessary. I argue that no logical reason exists for the use of dignity as a relative individual right with any substantive content (meaning) other than the protection of reputation and honour, because the other individual rights are worthy of protection themselves without the need to be ‘identified’ with human dignity as a relative individual right. For example, why should we use dignity as a right to life when the right to life itself is explicitly protected by almost every international and national catalogue of human rights? Dignity is not a right to live, because the right to life is a right to live. Similarly, no need exists to use dignity, for example, as a prohibition of cruel treatment or punishment, because the right to physical and moral integrity provides equally strong protection in a substantively much clearer manner.

Moreover, I believe that using the broadened or empty hybrid functions of dignity can also lead to absurd situations where the courts need to resolve the conflict of two individual rights, each claiming to be human dignity, or two objective values, each (again) insisting on being human dignity. However, these conflicts are impossible to resolve logically. To ask what should be given priority, whether dignity understood, for example, as the right to protect one’s reputation, or dignity understood, for example, as the right to freedom of speech, is the same as asking whether one kilogram of iron bars or one kilogram of feathers is heavier. The answer in both situations is that it cannot be decided since both are equally important (heavy) until we abandon the restrictions given by the term ‘dignity’ (or the unit of one kilogram). When we remove ‘one kilogram’, we can finally state that the answer which is heavier depends on the volumes and densities of iron bars and feathers. In other words, the result in the specific case depends on the circumstances of the individual case. This is precisely what makes weighing (i.e. using the rules of proportionality to solve the issue of conflicting individual rights) possible. Footnote 91

If, however, dignity (or one kilogram, to continue with the analogy) remains on both sides of the dispute, the conflict can be overcome (once again) only by using axioms which assume that one of the conflicting meanings of dignity is somewhat ‘more dignitarian’ (i.e. closer to the dignity of higher, and ideally absolute, argumentative power) than the other and should therefore outweigh its conflicting opponent (i.e. that iron bars are heavier than feathers regardless of their actual mass in a specific case). As in the previous problem caused by applying the strengthened and absolute functions of dignity, the proportionality test cannot be applied properly, even in this case. Instead of proper weighing, the only usable tool is a ‘deformed proportionality test’ which does not analyse which of the conflicting individual rights should be given priority, but rather which of them is generally ‘more dignitarian’ than the other. Footnote 92

Numerous cases of conflict between ‘two dignities’ can be found, for example, in Israel, Footnote 93 Germany, Footnote 94 and the USA. Footnote 95 For a deeper analysis, I examined a judgment of the Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic, Footnote 96 where the problematic nature of the ‘deformed proportionality test’ is demonstrated. In this case, the Court needed to answer whether it was constitutionally acceptable to release archival documents which contained sensitive personal data from the communist era. The Court set up the dispute as a conflict between dignity understood as the privacy and reputation of people whose personal information is contained in the archival documents (i.e. those who were investigated and persecuted by the communist authorities) and dignity understood as the right to access information by the family and friends of the investigated and persecuted persons concerning their fate.

Although the Court could have solved the dispute as an ‘ordinary’ conflict of several relative rights which can be balanced, it transformed the argumentative arena into a dignitary one by applying the strengthened (i.e. axiomatic) hybrid function of dignity. More specifically, the Court held that individual rights to personality, privacy, family life, and dignity are ‘absolutely necessary conditions for the dignified existence of man’. Footnote 97

Consequently, a proportionality test between the conflicting rights became impossible because dignity – being not only the balanced right but also the criterion for balancing itself – would always prevail. This ‘forced’ the Court to set dignity on the other side of the balance: the Court claimed that ‘the denial of the right of other interested persons from the circle of the persecuted (i.e. the persecuted persońs family members, relatives, friends, descendants) to access archives containing the persecuted persońs personal information, would force such interested persons to remain in undignified ignorance of the destiny of the persecuted person’. Footnote 98 Associating the right to information with human dignity allowed the Court to overcome the disadvantage of this right when it faced the axiomatic function of dignity as reputation and privacy, and consequently, it was able to hold that the right to information takes precedence over the inviolable right to dignity (as reputation), Footnote 99 because it is, after all, also a right to dignity.

I find the outcome of the ‘deformed proportionality test’, in which dignity as one right is balanced against dignity as another right using a criterion which again is human dignity, completely arbitrary. The court may simply choose one of the balanced dignities and hold that this dignity is more dignitarian and therefore must take precedence. In the case above, the Court gave priority to dignity understood as the right to information. However, the dissenting opinion of 7 of the 15 judges, written by Judge Rychetský, stressed that once human dignity understood as a right to reputation and privacy was raised, it should have been given priority since they saw ‘an insurmountable limit in the fact that the interest in “knowledge of the past” cannot prevail if the statutory regime of viewing should result in an interference with the dignity of the persons concerned’. Footnote 100 Therefore, if at least one judge had changed their mind, the result of the deformed proportionality test could have been the converse.

Regardless which of the balanced dignities prevails, the problems of arbitrariness and unpredictability in the decision remain the same. This is so because the only argument which can be used to resolve the deformed proportionality test is an axiomatic argument which associates dignity as a balanced entity with dignity as a criterion for balancing. In other words, when a broadened or empty function of dignity is used, it necessarily leads to the use of a strengthened or absolute function of dignity to overcome these problems.

In this section, I show that two potential problems emerge as a result of using either the strengthened and absolute or broadened and empty hybrid functions of human dignity. These problems disable the use of rational and proportional legal argumentation, replacing it with the need to use axioms, which are (in the context of legal argumentation) argumentative fouls which jeopardise the principles of a fair trial, legitimate expectations, and legal certainty centred in the normative ideal of the rule of law. Footnote 101 Moreover, these two types of hybrid function are mutually supportive or even constitutive. Once one of the hybrid functions is used as a legal argument, it encourages the use of the other. Finally, I would like to state that, as shown in Table 2, these two types of hybrid function can be combined. This can lead to an accumulation and intensification of the problems they cause, making their use even more dangerous.

Avoiding hybrid functions

This section aims to suggest a solution to the problems associated with the use of hybrid functions of human dignity in legal argumentation and especially judicial reasoning. The core of the suggested solution must (naturally) implement a set of principles which enable us to avoid or minimise the use and negative impact of hybrid functions.

A good starting point would be the attempt already accomplished by Shultziner, who offered a set of four principles which argued that ‘the application of human dignity in judicial decisions should be based on a written law’ (i.e. written background), ‘judges should try to define what human dignity is and be explicit about its meaning’ (i.e. clarity), ‘judges should attempt to use human dignity consistently in the same rulings and in future decisions’ (i.e. consistency) and ‘human dignity should advance human rights rather than limit them’ (i.e. fostering of rights). Footnote 102

This set of principles, however, needs to be adjusted for the purposes of a functional approach, in the following manner: (a) courts should use only those functions of human dignity which are explicitly contained in a written law; (b) if a written law explicitly contains more than one function of human dignity, courts should explicitly define which function is applied in the decision; Footnote 103 (c) if a written law explicitly contains a hybrid function (or functions) of human dignity, courts should interpret them as restrictively as possible and consistently apply this restrictive interpretation.

Shultziner’s third principle is unnecessary for basic functions, as consistency is either required as a result of the first principle (if a written law explicitly contains only one of the functions of human dignity) or not required at all (if a written law contains more than one basic function, enabling a court to choose different functions in different cases). It is also worth noting that Shultziner’s fourth principle is not included, as several of the functions, including two basic functions, can be proportionally weighed against conflicting individual rights or values and consequently legitimately outweigh and limit them in individual cases.

In a deeper examination of the adjusted general principles, we find that they can lead to several specific situations which could be solved by the following sub-principles. First, if a written law does not contain human dignity or if it is contained only in a not directly enforceable segment such as the preamble, the only possible basic function which can be used is human dignity as a source of human rights. In other words, dignity, in this case, cannot be applied directly or indirectly as a legal argument but may serve as an interpretative framework for judicial reasoning. This is the case, for example, in the European Convention on Human Rights or The Constitution of the United States.

Second, if a written law explicitly contains one basic function of human dignity, courts should use only this explicitly mentioned function. Examples are the Constitution of Sweden, which contains dignity as a source of human rights, Footnote 104 and the Constitution of San Marino, which contains dignity as an objective value. Footnote 105

Third, if a written law explicitly contains more than one basic function of human dignity, courts should in every decision transparently choose only one rather than a combination of more. This principle would apply, for example, to the Constitution of Slovakia, which contains all three basic functions, i.e. the relative individual right, Footnote 106 objective value, Footnote 107 and source of human rights. Footnote 108

Fourth, if it is not clear which function (or functions) of human dignity the written law contains, courts should interpret and use the function as a basic function rather than a hybrid function. For example, the preamble of the Constitution of the Czech Republic mentions the spirit of the inalienable values of human dignity and freedom. Dignity here can therefore be understood as an absolute value (hybrid function) or a source of human rights (basic function). The former interpretation can be supported by the text itself since the preamble explicitly refers to inalienable values. However, in favour of the latter interpretation, the following can be mentioned: (a) the text is contained in the preamble; (b) not only dignity but also freedom is characterised as inalienable, which could thus potentially cause unsolvable conflicts if both are applied as legal arguments before the courts; (c) the Czech Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms, which concretises the spirit mentioned in the preamble into enforceable provisions, contains dignity as a source of human rights Footnote 109 and as a relative individual right Footnote 110 but not as a value. Since both options are theoretically possible, the fourth principle states that the latter understanding should be applied to avoid the hybrid function.

Fifth, if a written law explicitly and clearly contains a hybrid function of human dignity, the courts have no other option than to use it. The interpretation should, however, be as restrictive as possible to prevent the combination of different types of a hybrid function. Hence, in the case of a strengthened or absolute function, courts should specify its substantive meaning and consistently apply it while avoiding any extensive interpretations. An example is the Basic Law of Germany, which states that ‘Human dignity shall be inviolable. To respect and protect it shall be the duty of all state authority’. Footnote 111 The inviolable [unantastbar] character of dignity clearly refers to it as an absolute function. According to the fifth principle, the proper approach should therefore be to interpret the substantive meaning of dignity as narrowly as possible and consistently apply dignity in only this specific interpretation.

In the case of a broadened or empty function, courts should, in the same manner, minimise its argumentative power and consistently avoid its strengthening or absolutisation. For example, the previous Constitution of Hungary stated that ‘(1) In the Republic of Hungary, everyone has the inherent right to life and to human dignity. No one shall be arbitrarily denied of these rights. (2) No one shall be subject to torture or to cruel, inhuman or humiliating treatment or punishment. Under no circumstances shall anyone be subjected to medical or scientific experiments without his prior consent’. Footnote 112 It is clear from the context that dignity is understood as an individual right, and yet it does not mean the right to protect one’s reputation and can therefore be classified as a broadened function. Hence, according to the fifth principle, the proper approach should be to use dignity as a broadened relative individual right to avoid its strengthening or absolutisation. More specifically, the right to dignity should be understood as limitable if: (a) its limits are not arbitrary; and (b) the absolute prohibitions included in the second paragraph of the cited article are respected.

Finally, if a written law contains both basic functions and hybrid functions of dignity, the courts should prefer the use of the basic function to minimise axiomatic argumentation. A good example of this is the Constitution of South Africa, which contains the functions of empty value, Footnote 113 source of human rights, Footnote 114 empty relative individual right, Footnote 115 broadened relative individual right, Footnote 116 and objective value. Footnote 117

The application of these six sub-principles should minimise the emergence of hybrid dignitary functions in legal argumentation and consequently enable courts to avoid the problems these functions cause. Principles 1, 2, and 3 should eliminate the creation of hybrid functions by courts without a basis in written law. Principles 4 and 6 should significantly lower the frequency of hybrid functions in legal argumentation, even in cases where hybrid functions are stated in written law. Finally, principle 5 serves as an instrument to minimise the negative effects of hybrid functions on legal argumentation in situations where their use is unavoidable.

My final remark is that these sub-principles also take into account the variety of substantive meanings of human dignity, not only across countries but also within individual legal systems (i.e. context-dependency of human dignity). The application of these principles should not reduce the construct’s diversity. On the contrary, it allows diversity to be maintained while avoiding the potential problems in legal reasoning that could be caused by such diversity. In other words, avoiding the problems caused by the hybrid functions of human dignity (i.e. the cause) would naturally assist in solving the problems caused by the variety of its substantive meanings (i.e. the symptoms).

Conclusion

The article introduced a comprehensive theoretical framework for dignitary legal argumentation based on a functional approach. The article presented two important reasons why focusing exclusively on functions instead of content is more productive.

First, analysis of the functions is methodologically easier. While perhaps infinite possible substantive meanings of human dignity exist, a functional approach based on three analytical criteria (i.e. content width, argumentative power, and applicability before courts) enables the identification of only three separate basic functions of this construct in legal argumentation, namely the relative individual right, the source of human rights, and the objective value. This simplification allows a comparison of not only constitutional and international documents but also case law across nations, with less influence from the cultural specifics of these countries.

Second, the functional perspective enables us to bypass the problems caused by the variety of substantive meanings of human dignity and address the key issues of the construct, which can be identified as misunderstandings regarding its functions rather than its substantive meaning. I argue that the critical problem lies in the creation of hybrid functions of human dignity created by combining the characteristic features of more than one basic function. The article explains why the use of hybrid functions is an argumentative foul which causes axiomatisation of the legal argumentation and consequently reduces the quality, soundness, persuasiveness, and predictability of legal reasoning. A potential solution to this problem is the set of six sub-principles discussed in the article. These principles should provide the tools to minimise the emergence of hybrid functions of dignity and its negative effects in legal argumentation. They should facilitate high-quality dignitary legal reasoning while maintaining the diversity of substantive meanings of human dignity.