Principle of equality of elections in Polish Constitution pertains to all types of self-government elections – Direct consequence of the constitutional guarantee of equality of all citizens before the law – Provisions of the 2011 Polish Election Code on procedures for creating single-seat constituencies – Substantive equality does not apply in the case of elections to councils of small and middle-sized communes – Permissible departures from the demographic norm regulating the size of constituencies – Possible size discrepancies between individual single-seat constituencies (1:3) lead to serious disparities between residents of the same commune in their potential impact on local self-government institutions – Compatibility with standards concerning the substantive equality of elections formulated in the Code of Good Practice in Electoral Matters by the Venice Commission

Introduction

The principle of equality of elections plays an important role in the process of establishing who are the power elites in democratic societies. It is widely believed that it, along with the principles of universality, directness and secrecy of elections, is one of the foundations of the electoral system. With the restoration of democracy in Poland after the period of the Communist regime, these principles have been recognised by Polish legal scholars as the basic assumptions underlying all kinds of procedures shaping the political representation of citizens (at both the national and local level), which ultimately determine their democratic nature.Footnote 1 ‘Thus, if these principles are not actualised’, writes Garlicki, ‘the elections by definition cannot have a democratic character’.Footnote 2 Determination of the fundamental character of the electoral principles is accompanied in most cases by a recognition of their equal weight as specific safeguards against abuses of the democratic system of government: in a variety of studies dealing with electoral law they are most frequently considered together, without being in any way hierarchised. Nevertheless, as noted by Dudek, each of them is characterised by a different ‘axiological potential’: universality and equality are related, in his view, to substantive justice, whereas directness and secrecy relate to the procedural fairness of elections, the essential point being that the ‘realisation of universality of elections necessarily implies respect for their equality’ (with the contemporary, i.e. fully egalitarian and prejudice-free meaning of ‘universality’ underlying the latter statement).Footnote 3

The profound significance of the general principles of democratic elections is the main factor behind their being proclaimed directly in most modern constitutions, whereby they gain the status of fundamental rules underlying the whole system of public governance.Footnote 4 In the case of Poland, the constitutionalisation of those principles is effected by the Constitution of the Republic of Poland in Articles 96 § 2 (elections to the Sejm, the lower chamber of the Polish Parliament), 97 § 2 (elections to the Senate), 127 § 1 (presidential elections) and 169 § 2 (local elections). Three of the four electoral procedures – for election to the Sejm, to the office of President of the Republic and to legislative bodies representing territorial units – are characterised in the aforementioned provisions of the Constitution as being compliant with the principle of equality. Polish constitutional law does not, however, ascribe the characteristic of equality to elections to the Senate.Footnote 5

Critically important to the fairness of electoral procedures, the principle of equality of elections nonetheless constitutes a significant challenge for legislators, especially with regard to its substantive aspect, i.e. the fixed ratio between the number of seats electable in any constituency and the number of residents in it, or the number of citizens/residents eligible to vote/actually voting for any of the contenders for the seats in question. In line with internationally accepted standards, substantive equality of elections can be implemented by taking into account any of the following features of the constituencies in which elections are held (or a combination thereof): their total population, the number of resident nationals (including minors), the number of registered voters, or the number of people actually voting.Footnote 6 The most efficient way to ensure strict implementation of that aspect of electoral equality amounts to holding elections in a single national constituency (or, in the case of local elections, a single constituency covering the whole territorial unit whose representative body – e.g. the local council – is being elected). As such a solution might in most cases entail a disproportionate distribution of political significance between parts of the electorate residing in different regions/localities – the densely populated administrative centres gaining an unfair advantage over the remaining parts of the country/territorial unit – in most electoral systems an adequate territorial balance of national/local policy-making is sustained by division of the country/territorial unit into smaller constituencies. One possible arrangement aimed at the direct anchoring of a national/local government’s political legitimacy in an evenly-structured electoral area is a system of single-seat constituencies. It is the rules by which such constituencies are created that become crucial to the preservation of the substantive equality of elections. In formulating such rules, especially careful attention is needed in the event a system of single-seat constituencies is meant to function alongside a proportional system and regulate only certain electoral procedures (e.g. local elections in a specific type of territorial unit). An attempt to devise a versatile set of election law provisions concerning the formation of constituencies – both single and multi-seat, the latter type used in the proportional system – while disregarding the key mathematical differences between the two systems, might result in a manifest failure to protect the substantive equality of elections.

The Election Code, passed in January 2011 by the Polish Sejm, introduced into Poland’s election law, for the first time, a requirement to create single-seat constituencies in elections for councils in communes which are not cities with county rights.Footnote 7 Thus, in 97.7% of the territory of the country, inhabited by 67% of its population,Footnote 8 elections for self-government bodies of basic territorial units turned into procedures implementing the classic type of the first-past-the-post electoral system. Although the new law was passed almost unanimously, it was presented by the Polish, liberal-leaning party Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska) – which, at the time, formed a ruling majority with the Polish Peasant Party (Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe) – as evidence of its long-term commitment to promoting greater empowerment of the electorate. By maximally simplifying the election procedure – and thus entrusting to voters, to the greatest possible extent, the appointment of their representatives in county councils – the new regulations were expected to put a curb on party politics at the local government level. The single-seat constituencies were supposed to prove highly instrumental in identifying/forging local leaders capable of challenging the entrenched political establishment (which is clearly privileged in the proportional system, e.g. due to its being in charge of preparing strictly hierarchised candidate lists for local councillorships).

A particularly sensitive aspect of the 2011 regulations enforcing the formation of single-seat constituencies in all small and middle-sized communes was the way in which they afforded protection to one of the most fundamental features of local elections, namely their constitutionally guaranteed equality. Analysis of the relevant provisions of the Election Code and their mode of application by local councils in the period 2011–2018 clearly demonstrates that, under current Polish legislation dating back to the passing of the Election Code in 2011, equality of elections to these councils, regarded substantively, has not been properly secured.Footnote 9 With permissible deviations from the relevant substantive-equality-benchmarks of up to 50% (internationally recognised standards in this respect prescribe that such deviations be no more than 10% or, in special circumstances, 15%), potential size discrepancies between individual single-seat constituencies can reach levels of almost 200% (1:3), which, in turn, leads to serious disparities between residents of the same commune in their potential impact on local self-government institutions. Unaccompanied by a thorough review of the provisions related to substantive equality of elections, enforcement of the basic version of first-past-the-post in Polish local elections was the culmination of prolonged piecemeal tinkering with election law, and as such appears to have been an example of an intrinsically flawed reform of a fundamentally important, constitutionally sensitive, piece of legislation.

The current paper analyses the basic constitutional flaw inherent to the substantive-equality-related provisions of the Polish Election Code, and consists of five parts. It begins with a brief outline of the concept of substantive equality of elections as interpreted in Polish constitutional law. The second part of the paper presents a short history of modifications to the 1990 legislation on the substantive equality of Polish local elections (as well as some modifications to the corresponding regulations governing Polish parliamentary elections inasmuch as they impacted the standards of equality of local elections), and thus provides an essential background to the discussion on current provisions of Polish election law concerning that matter. In the third part, the provisions in question are analysed in detail, and a simple mathematical formula is proposed to demonstrate a glaring discrepancy between standards of substantive equality in elections to councils of small and middle-sized communes and standards in other types of election. The potential consequences of applying the substantive-equality-related provisions of the Election Code are illustrated in the fourth part of the paper, a discussion of a hypothetical case of a commune divided – in full compliance with Polish election law – into strikingly unequal single-seat constituencies. Finally, a short review is presented of the reception by Polish legal scholars of the Code of Good Practice in Electoral Matters prepared by the Venice Commission, including very detailed guidelines for the implementation of substantive equality of elections. With the overt departure from these guidelines in the relevant provisions of the Election Code of 2011, and the lack of any serious debate on that issue in Poland in recent years, the survey of the opinions of Polish leading jurists concerning the normative status of guidance offered by the Venice Commission is very intriguing, even more so now in the context of fierce debate on purported violations by the current Polish legislature of the principle of constitutional supremacy and the rule of law – as pointed out by the very same Venice Commission.

Substantive equality of elections in Polish constitutional law

Established doctrine of Polish constitutional law distinguishes between two aspects of electoral equality. Formal equality means that, in elections to representative bodies, each voter has the same number of votes as other voters and can only vote once.Footnote 10 Considered substantively, equality of elections is a guarantee of equal voting power for each voter, i.e. it ensures that any vote cast impacts the final outcome of the election in the same (or a very similar) way as any other vote cast.Footnote 11 In order to fully implement the principle of electoral equality, both aspects must be taken into account: guaranteeing merely the formal equality of voting might easily lead to a more or less disproportionate distribution of political significance among the various parts of the electorate (e.g. two groups of voters consisting of, respectively, 1,000 and 10,000 people, each group having the right to elect 10 representatives, with every individual voter voting only once). It is widely believed that the principle of equality of elections is a consequence of the constitutional principle of equality before the law expressed in Article 32 § 1 and 2 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland.Footnote 12

The distinction between the formal and substantive aspects of the equality of the vote, as recognised in Polish jurisprudence, corresponds to analogous distinctions upheld within other jurisdictions. French constitutional law distinguishes between numerical equality (égalité de décompte), which guarantees each voter the same number of votes (the principle of ‘one person, one vote’), and equality of representation (égalité de représentation), thereby ensuring an adequate division of the electoral territory into constituencies whose number of electable seats is proportionate to the number of inhabitants.Footnote 13 Similarly, according to the German Constitutional Court, each vote cast needs to have the same numerical value and the same legal chance of success (den gleichen Zählwert und die gleiche rechtliche Erfolgschance). The latter is secured in the first-past-the-post system by a delimitation of constituencies ‘as equal as possible in size’ (möglichst gleichgroßer Wahlkreise), and in the proportional system by deployment of a method of distribution of mandates to particular lists of candidates such that each voter has the same degree of influence on the composition of the elected body.Footnote 14 An analogous approach to the concept of electoral equality is taken by Czech constitutional jurists; they emphasise – with reference to the proportional system – the equal weight of each vote cast in support of a given party in relation to the number of mandates gained by the party.Footnote 15 It is interesting that US electoral jurisprudence, which is based entirely on the principle of ‘one person, one vote’, seems to take the numerical equality of each vote for granted and is almost entirely preoccupied with the idea of the demographically equal and socially unbiased delineation of single seat constituencies. Thus, in a famous ruling, the US Supreme Court presented the principle of equal voting power as stemming from the ‘one person, one vote’ principle.Footnote 16 In contrast to the constitutional regimes of many countries, the European Convention on Human Rights does not enshrine, nor do the corresponding rulings of the European Court of Human Rights uphold, the principle of equality of elections.Footnote 17

In the opinion of most constitutionalists, implementation of the principle of substantive equality of elections involves ensuring that – in the process of creating constituencies for elections to a given representative body and then attributing to them a particular number of electable seats – the number of seats attributed to each of these constituencies is proportionate to the number of people living in that constituency.Footnote 18 The key issue, therefore, is whether the boundaries between these constituencies have been drawn, first and foremost, in full compliance with the requirement to maintain a constant ratio between each electable seat and the number of citizens (inhabitants of a local community) to which it is assigned. According to the Polish Election Code, when drawing a map of constituencies one should employ a strictly defined parameter – calculated separately for each type of election – known as the uniform standard of representation.Footnote 19 In the case of elections to commune councils, this is the number which results from dividing the total number of residents of a commune by the number of seats in the council of that commune. The general understanding of the principle of substantive equality of local electionsFootnote 20 precludes any substantial deviation from strict application of this parameter in the delimitation of constituencies: each member of the council should have a similar number of residents of the commune assigned to him/her (one should obviously allow for some small deviation due to specific circumstances occurring in individual communes). A permissible departure from the uniform standard of representation as defined in Polish legislation should be exceptional, and must always be justified by an appeal to rational considerations.Footnote 21

In order to determine the precise normative potential of the principle of equality of elections, i.e. to specify the maximum allowable deviation from a strict mathematical application of the uniform standard of representation, it is necessary to refer to the notion of so-called fixed concepts.Footnote 22 When establishing the principle in question in the provisions of the Constitution or any ordinary legislative act, legislators ‘do not redefine its content, providing its legal definition, but assume that the meaning of the principle has already been determined in the course of its historical development’.Footnote 23 The lack of definitional clarity regarding the substantive aspect of the principle of equality of elections implies that when determining the meaning of this principle, it is necessary to refer to the ideas and solutions put forward in the process of the democratisation of Poland’s electoral system (which itself can be understood as having been influenced by the development of international standards in this field).

A blueprint for establishing the specific numerical requirements stemming from the principle of substantive equality of local elections can be found in a set of provisions contained in the Act of 8 March 1990 – Electoral Law for Commune Councils (hereinafter the Electoral Law of 1990). The law enjoined taking into account – in the process of drawing boundaries between constituencies – the territorial, economic and social factors impacting the interests of and mutual relations between residents of the constituency being created; in subsequent modifications of the electoral law, this requirement was replaced by an obligation to take into account – when creating constituencies – formally established auxiliary units of a commune such as the village community (sołectwo), district, ward, housing estate or settlement (kolonia).Footnote 24 At the same time, Article 13 of the Electoral Law of 1990 specified, for each constituency, a permissible range of deviation from the uniform standard of representation, and therefore also for single-member constituencies, the creation of which in communes/cities whose resident population is equal to or smaller than 40,000 had been ordered by Article 12 § 1 of the act: ‘With the creation of constituencies for the elections to the council one must apply the uniform standard of representation resulting from dividing the number of inhabitants of the commune (city) by the number of councilors set for that council. Deviations from the standard of representation specified in this way are allowed within the limits of 20 per cent, if it is justified on the grounds set out in Article 11 § 2 and 3’.Footnote 25

The slippery slope: from compromising the clarity of electoral-equality-related regulations to legislating (unconstitutional) inequality of local elections

The history of modifications to Polish electoral legislation after 1990 is marked by a gradual lowering of standards concerning the implementation of substantive equality of local elections. By passing the Act of 16 July 1998 – Electoral Law for Councils of Communes, County Councils and Regional Councils (hereinafter the Electoral Law of 1998), which replaced the Electoral Law of 1990, Polish legislators abandoned the idea of providing detailed rules governing permissible deviation from the uniform standard of representation in creating constituencies for elections to the councils of communes. Although Article 91 of the Electoral Law of 1998 preserved the obligation to apply the uniform standard representation in the creation of these constituencies; deviations from this standard were only allowed if they served to maintain the territorial integrity of individual village communities (sołectwo) intended to constitute ‘natural’ constituencies in rural communes. The provisions of the new law – in contrast to those of the Electoral Law of 1990 – did not specify the legitimate extent of such deviations.Footnote 26 The legislature’s acting on the presumption of the existence of limits to such deviations was confirmed by the content of Article 89 § 3 of the Electoral Law of 1998, according to which the division of particular village communities into two or more constituencies was allowed ‘only if the number of councilors elected in a village community was greater than that provided for in Article 90’, i.e. greater than five in communes with up to 20,000 residents and greater than 10 in communes with over 20,000 residents.Footnote 27 At the same time, the Electoral Law of 1998 did not enforce the creation of single-seat constituencies in any communes, and thus made it possible to circumvent the problem of potential violations of substantive equality of elections:Footnote 28 in Article 90 § 1, it left the issue to be decided by the councils of the individual communes in question.

Despite a lack of appropriate regulations in the Electoral Law of 1998, immediately after the act came into force it became common practice to apply – in the process of creating constituencies for elections to commune councils – the corresponding provisions relating to the elections to county (powiat) councils. The constituencies were thus first roughly delimited by taking into account the territorial/social cohesion of specific areas, and then readjusted according to the presumed substantive equality requirement, i.e. the rule formulated with regard to constituencies used in elections to county councils: ‘a fraction of the number of seats electable in a constituency equal to or greater than 1/2, which results from the application of the uniform standard of representation, shall be rounded up to the nearest integer’.Footnote 29

Up to 2001, the aforementioned procedure, i.e. a simple implementation of the mathematical formula of rounding up decimal fractions of the universal standard of representation to the nearest integer, was also used for the preliminary delimitation and subsequent readjustment of parliamentary constituencies for elections to the Sejm (the lower chamber of the Polish Parliament).Footnote 30 At the same time, both in the Act of 28 June 1991 – Electoral Law for the Sejm of the Republic of Poland – as well as in the Act of 28 May 1993 which replaced it, the content of provisions aimed at maintaining a constant ratio between a single mandate and the number of residents attributable to it amounted to requiring that the boundaries of constituencies, as well as the number of deputies elected by them, be determined ‘in compliance with the uniform standard of representation’.Footnote 31 The principle defining how to round up fractions of mandates when calculating the number of seats per constituency created for elections to the Sejm was articulated only in the Act of 12 April 2001 – Electoral Law for the Sejm and the Senate of the Republic of Poland. The relevant provision of the act was worded almost identically to Article 136 § 1, point 1, of the Electoral Law of 1998.Footnote 32

In 2002, analogous modifications were introduced into the provisions of the Electoral Law of 1998 concerning the creation of constituencies for elections to commune councils.Footnote 33 Legislators thus accomplished a seemingly successful unification of the law on application of the concept of the uniform standard of representation in creating constituencies for parliamentary elections, with the law on elections to local self-government bodies. The provisions in question were subsequently transferred, substantially unchanged, to the Election Code passed by the Polish Sejm – by an almost unanimous vote – on 5 January 2011.

The provisions of the Election Code concerning the substantive equality of elections to commune councils

The principle of equality in local elections set forth in Article 169 § 2 of the Polish Constitution is repeated in Article 369 of the Election Code. With regard to elections to the Sejm and election of the President of the Republic of Poland, the principle of equality of elections finds its statutory anchoring in Articles 192 and 287 of the Election Code respectively.Footnote 34 Since the Code was enacted, all three provisions intended to ensure equality in the various election procedures have thus become components of a single normative act. It should be emphasised that enactment of the Election Code to replace previous electoral laws was widely welcomed by both Polish legal scholars and representatives of Poland’s electoral administration as an opportunity to move away from ‘the multiplicity of legal acts regulating election procedures’, as well as from ‘incomprehensible discrepancies in dealing with the same issues in different laws’.Footnote 35

Until 1 January 2019, the preliminary delimitation and final adjustment of the boundaries of constituencies in particular communes – crucial for enforcement of substantive equality of elections – is entrusted to the councils of those communes.Footnote 36 The division of a commune into constituencies is to be made ‘in compliance with a uniform standard of representation calculated by dividing the number of inhabitants of the commune by the total number of councillors elected to the council’, with ‘a fraction of the number of mandates elected in constituencies equal to or greater than 1/2, which arise from the application of a uniform standard of representation, [to] be rounded up to the nearest integer’.Footnote 37 The implementation of substantive equality of elections in the case of elections to commune councils in general is also significantly affected by a number of other regulations such as the recognition of auxiliary units of a commune as ‘natural’ constituencies in rural communes, the requirement to take into account – when creating constituencies in towns and cities – the established auxiliary units of these towns (cities), and the specification of the method of distribution of mandates following the announcement of election results (Article 443 and Article 444).Footnote 38 However, taking into account the specific content of the provisions of the Election Code concerning the application of a uniform standard of representation in the creation of constituencies, one cannot fail to notice that the efficiency of enforcement of substantive equality of elections ensured by these regulations ultimately depends on the provisions regulating the minimum number of seats electable in one constituency. It is these provisions of the Polish Election Code that substantiate the claim that – in the case of the elections to councils of villages and small cities – the principle of substantive equality of elections does not, in fact, apply.

If the actual parameters determining the voting power of a single voter are considered, the achievement of consistency of the Election Code with regard to its provisions aimed at securing substantive equality of elections turns out to be illusory. Despite the almost identical wording of the corresponding provisions,Footnote 39 the way in which they determine the implementation of the principle in question is completely different with respect to elections to the Sejm, on the one hand, and elections to councils of communes which are not cities with county rights, on the other. In either case, the actual content of the statutory guarantee of substantive equality of elections manifests itself only when one considers the relation of the aforementioned provisions to, respectively, Arts 201 § 2 and 418 § 1 of the Election Code.Footnote 40 While the former constitutes a literal restatement of the earlier regulationFootnote 41 (in force until adoption of the Election Code), the latter reintroduces to the Polish electoral system – after a hiatus of a dozen or so years – the principle of obligatory single-seat constituencies for elections to all village councils and the councils of towns and cities with a population equal to or smaller than 20,000.Footnote 42

The regulations in question determine the number of seats per constituency in elections to the Sejm and elections to the councils of villages, towns and small cities; they dictate an identical procedure for rounding up fractions of that numberFootnote

43

to generate the maximum permissible deviation from the uniform standard of representation, i.e.

![]() ${1 \over {14}}$

(or roughly 7%) for the Sejm, and almost

${1 \over {14}}$

(or roughly 7%) for the Sejm, and almost

![]() ${1 \over 2}$

(i.e. 50%) in the latter case. Both numbers are the result of dividing the largest decimal constituting a downward deviation from a strict application of the uniform standard of representation in determining the number of seats allocated to a constituency by the minimum number of seats electable in it, i.e. equal distribution among all the individual mandates attributable to a given constituency of the ‘shortage of population’ demonstrated by that constituency in relation to the minimum number of these mandates. With regard to the constituencies created for elections to the Sejm, the calculation in question takes the following form:

${1 \over 2}$

(i.e. 50%) in the latter case. Both numbers are the result of dividing the largest decimal constituting a downward deviation from a strict application of the uniform standard of representation in determining the number of seats allocated to a constituency by the minimum number of seats electable in it, i.e. equal distribution among all the individual mandates attributable to a given constituency of the ‘shortage of population’ demonstrated by that constituency in relation to the minimum number of these mandates. With regard to the constituencies created for elections to the Sejm, the calculation in question takes the following form:

![]() ${1 \over 2}$

of the uniform standard of representation divided by seven (the minimum number of seats in a constituency to the Sejm) equals

${1 \over 2}$

of the uniform standard of representation divided by seven (the minimum number of seats in a constituency to the Sejm) equals

![]() ${1 \over {14}}$

(roughly 7%) of the uniform standard of representation; with regard to elections to the councils of villages, towns and small cities it is as follows:

${1 \over {14}}$

(roughly 7%) of the uniform standard of representation; with regard to elections to the councils of villages, towns and small cities it is as follows:

![]() ${1 \over 2}$

of the uniform standard of representation divided by 1 (the number of seats in a constituency created for elections to a commune council) equals

${1 \over 2}$

of the uniform standard of representation divided by 1 (the number of seats in a constituency created for elections to a commune council) equals

![]() ${1 \over 2}$

(50%) of the uniform standard of representation.

${1 \over 2}$

(50%) of the uniform standard of representation.

A similar calculation concerning the cases of rounding ‘down’ the fractions of seats electable in particular constituencies produces only marginally different results; this time the greatest decimal fraction of the uniform standard of representation making it necessary to round ‘down’ the number of seats assigned to a constituency should be divided by the minimum number of seats electable in it, i.e. one should equally distribute among all the individual mandates attributable to a given constituency the ‘excess of population’ demonstrated by that constituency in relation to the minimum number of these mandates. With regard to the constituencies created for elections to the Sejm, the calculation in question takes the following form: just short of

![]() ${1 \over 2}$

of the uniform standard of representation divided by seven (the minimum number of seats in a constituency to the Sejm) equals just short of

${1 \over 2}$

of the uniform standard of representation divided by seven (the minimum number of seats in a constituency to the Sejm) equals just short of

![]() ${1 \over {14}}$

(almost 7%) of the uniform standard of representation; and, correspondingly, with regard to elections to councils of villages, towns and small cities: just short of

${1 \over {14}}$

(almost 7%) of the uniform standard of representation; and, correspondingly, with regard to elections to councils of villages, towns and small cities: just short of

![]() ${1 \over 2}$

of the uniform standard of representation divided by 1 (the number of seats in a constituency created for elections to a commune council) equals just short of

${1 \over 2}$

of the uniform standard of representation divided by 1 (the number of seats in a constituency created for elections to a commune council) equals just short of

![]() ${1 \over 2}$

(almost 50%) of the uniform standard of representation.

${1 \over 2}$

(almost 50%) of the uniform standard of representation.

In terms of legally acceptable differences between the voting power of individual voters living in different constituencies, the abovementioned provisions make it possible that, in elections to the Sejm, the maximum voting power of an individual voter will be greater than the minimum voting power of another voter by up to

![]() ${2 \over {13}}$

(slightly more than 15%), whereas in elections to councils of villages, towns and small cities the same difference will amount to almost two (almost 200%). In other words, in the latter case the maximum voting power of an individual voter will be almost three times greater than the minimum voting power of a single voter – the luckier voter lives in a constituency that really ‘deserves’ half a seat but actually gets a whole seat, and the unluckier voter lives in a constituency ‘deserving’ of just short of 1

${2 \over {13}}$

(slightly more than 15%), whereas in elections to councils of villages, towns and small cities the same difference will amount to almost two (almost 200%). In other words, in the latter case the maximum voting power of an individual voter will be almost three times greater than the minimum voting power of a single voter – the luckier voter lives in a constituency that really ‘deserves’ half a seat but actually gets a whole seat, and the unluckier voter lives in a constituency ‘deserving’ of just short of 1

![]() ${1 \over 2}$

seats although it, too, gets just one seat. The maximum allowable difference in voting power of voters from two different constituencies in elections to a given representative body can be determined as follows: the largest allowable fraction of the uniform standard of representation attributable to one seat in a single constituency should be divided by the smallest allowable fraction of the uniform standard of representation attributable to one seat in a single constituency.Footnote

44

In the case of elections to the Sejm, this calculation becomes: just short of

${1 \over 2}$

seats although it, too, gets just one seat. The maximum allowable difference in voting power of voters from two different constituencies in elections to a given representative body can be determined as follows: the largest allowable fraction of the uniform standard of representation attributable to one seat in a single constituency should be divided by the smallest allowable fraction of the uniform standard of representation attributable to one seat in a single constituency.Footnote

44

In the case of elections to the Sejm, this calculation becomes: just short of

![]() $1 {1 \over {14}}$

/

$1 {1 \over {14}}$

/

![]() ${{13} \over {14}}$

=just short of

${{13} \over {14}}$

=just short of

![]() ${{15} \over {13}}$

(the maximum permissible difference in voting power is slightly more than 15%), while in the case of elections to councils of communes which are not cities with county rights: just short of 1

${{15} \over {13}}$

(the maximum permissible difference in voting power is slightly more than 15%), while in the case of elections to councils of communes which are not cities with county rights: just short of 1

![]() ${1 \over 2}$

/

${1 \over 2}$

/

![]() ${1 \over 2}$

=just short of 3 (the maximum permissible difference in voting power is almost 200%).

${1 \over 2}$

=just short of 3 (the maximum permissible difference in voting power is almost 200%).

In order to calculate, for a given constituency, the percentage of deviation of its real ‘share’ in the formation of the corresponding representative body from the uniform standard of representation calculated for that body, the (decimal) fraction (or the fractional deviation ‘downwards’ from the nearest integer) obtained when dividing the number of inhabitants of that constituency by the uniform standard of representation should be divided again by the number of seats electable in that constituency (i.e. the ‘deficiency’/‘excess’ of the constituency’s population in relation to the number of mandates attributable to it should be distributed equally among all these mandates). The greatest degree of that deviation will always be displayed by constituencies with the smallest number of seats attributable to them – the lower the number of seats, the greater the part of the equally distributed ‘shortage’/‘excess’ of the constituency’s population corresponds to each of them. One can observe the rate of change of the maximum allowable difference in voting power of individual voters taking part in different types of election in relation to the allowable scope of deviation (‘upward’ and ‘downward’) from the strict implementation of the uniform standard of representation in particular constituencies created for these elections by analysing the graph of the following function:

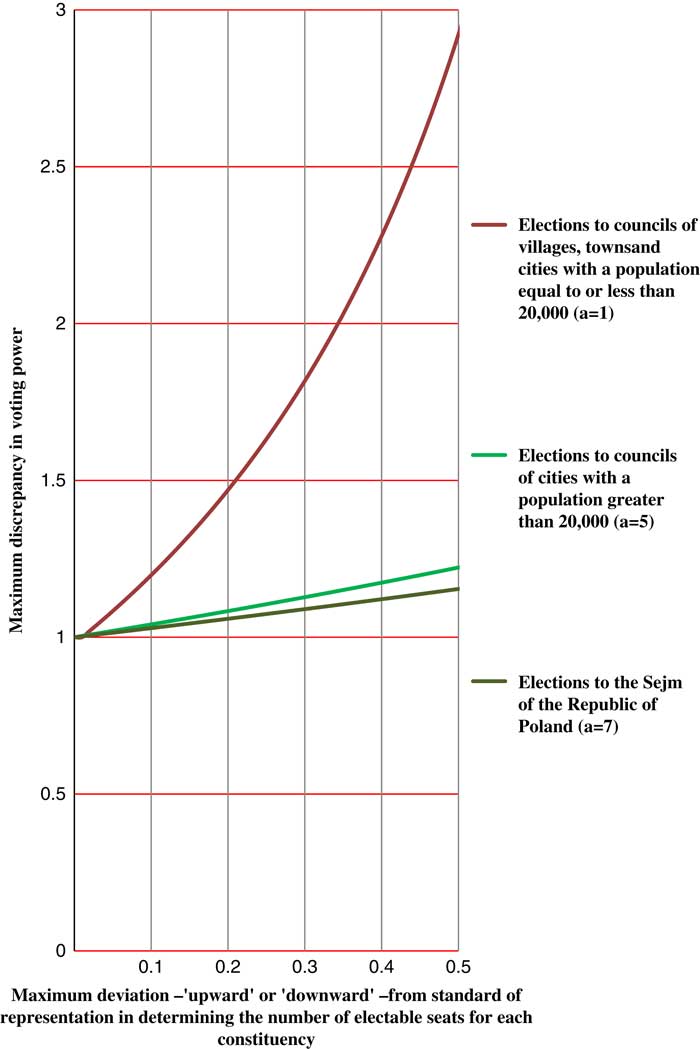

where ‘a’ is the minimum number of seats attributable to a single constituency, ‘x’ is any number in the range (0, 0.5) denoting the maximum allowable fractional deviation (either ‘upward’ or ‘downward’) from ‘a’, and ‘y’ is the ratio of the maximum possible fraction of the uniform standard of representation attributable to a single mandate in a constituency to the minimum possible fraction of the uniform standard of representation attributable to a single mandate in a constituency. Figure 1 presents three variants of the graph of the above function for three different values of ‘a’: 1) a=7 (constituencies created for elections to the Polish Sejm); 2) a=5 (constituencies created for elections to councils of cities with a population greater than 20,000); 3) a=1 (constituencies created for elections to councils of villages, towns and cities with a population equal to or smaller than 20,000). As one can see, in all three cases, the analysed functions grow more than linearly in the range from 0 to 0.5, but the growth turns out to be most spectacular for a=1, i.e. for the function demonstrating the consequences of the provisions of the Election Code concerning elections to councils of villages, towns and small cities.

Figure 1 Maximum discrepancy in voting power as related to maximum deviation from standard of representation (elections to the Polish Sejm, elections to cities with a population greater than 20,000, elections to cities with a population equal to or smaller than 20,000)

Both the content of the aforementioned provision of the Election Code as well as the guidelines of Poland’s National Electoral Commission addressed to community councilsFootnote 45 leave no doubt that the uniform standard of representation should be understood as a specific number – the ratio of the number of inhabitants of a commune to the number of councillors elected in that commune. It is by reference to this number that the initial division of the commune into particular ‘prototype’ constituencies is to be made – these provisional constituencies are then further adjusted in accordance with Article 419 § 2, point 1, of the Election Code.Footnote 46 One specific feature of elections to councils of small and middle-sized communes, i.e. the fact that they are held in single-seat constituencies, makes it possible however, to draw the boundaries between these constituencies – in full compliance with the mathematical requirements concerning the number of electable seats as well as the size of particular constituencies – based not on the uniform standard of representation understood as a specific number, but on the range of permissible deviations from that number – falling between 0.5 and 1.49 of the number in question – without even considering its significance as a benchmark of equal distribution of seats between constituencies (delineating multi-seat constituencies requires such a consideration, e.g. in multiplying the standard of representation by the allowable number of seats per constituency). It is important to note that such a procedure has obtained the full approval of the National Electoral Commission.Footnote 47

Consequently, it must be concluded that Article 419 § 2, point 1, of the Polish Election Code passed on 5 January 2011 read in conjunction with Article 418 § 1 of that Code could legitimise the creation of local self-government constituencies for elections to councils of villages, towns and small cities in such a way that the number of inhabitants of separate constituencies – and, consequently, the voting power of particular voters living in these constituencies – could differ from each other by nearly a factor of three.

It is difficult to think of any reason why the standards for statutory protection of substantive equality of elections are allowed to remain so drastically different in the case of elections to the Polish Sejm, on the one hand, and for elections to councils of villages, towns and small cities, on the other. Considered in the light of the above parameters, the abandonment of the original wording of the provision implementing the principle of substantive equality of elections in the Electoral Law of 1990, and putting in its place Article 92 § 2, points 1 and 2, of the Electoral Law of 1998, appears to have led to a completely unjustified abandonment of the universally recognised understanding of that principle. The direct transfer of the latter provision to the Election Code resulted in a situation in which existing regulations in this area suffer from the same defect. You could reasonably argue that the Election Code, by requiring – in its original wording of 5 January 2011 – the creation of single-member constituencies in all communes which are not cities with county rights,Footnote 48 caused the substantive equality of local elections to be distorted by this defect to an even greater extent: the Electoral Law of 1998 did not dictate the creation of single-seat constituencies in all such communes – it left the issue to be decided by the individual councils of the communes in question.Footnote 49 The recently amended version of Article 418 § 1 of the Election Code, in force since 31 January 2018, only slightly reduces the number of communes with mandatory single-seat constituencies (from 2,412 to 2,136) due to the introduction of a proportional system for middle-sized cities (i.e. with a population of over 20,000). At the same time, it leaves the general mode of implementation of substantive equality of elections principally unchanged.

It is worth noting that the legitimacy of creating single-seat constituencies with numbers of inhabitants differing by a ratio of 1:3 extends universally to all of the various above-mentioned communes. It concerns not only communes with established auxiliary units, such as the village community (sołectwo) and housing estate (osiedle), but also communes which do not have such units, e.g. cities with a completely uniform residential space. In the case of the latter, the threefold discrepancies between individual single-seat constituencies are legitimate both in the situation in which such differences could find some justification in the additional criteria related to the implementation of the principle of substantive equality of elections discussed by legal scholars, such as the criterion of a constituency’s economic, territorial, ethnic or religious unity (justifying e.g. the creation of demographically smaller constituencies covering large areas with a lower population density or demographically larger constituencies, covering smaller areas with a higher population density),Footnote 50 and in situations in which the demarcation of constituencies stands in direct contradiction to such criteria. One could, for instance, create demographically smaller constituencies that occupy a small area and demographically larger constituencies that occupy a vast area (a larger area always implies a greater diversity of interests among its inhabitants, a lower level of social integration, much more difficult contact between residents and councillors, etc – all of these complications intensify with the increase in number of people living in a given area).Footnote 51

A possible delineation of single-seat constituencies in a commune with a population of 15,000

The ultimate result of the division of a commune into single-seat constituencies – carried out, it must be emphasised, in full compliance with the provisions of the Election Code – can therefore amount to certain substantial and completely unjustified inequalities in the voting power of voters living in different parts of the commune. This may be expressed, among other ways, in:

(i) significant demographic disparities between the smallest and the largest constituencies;

(ii) the creation of enclaves of ‘miniature-constituencies’ and ‘giant-constituencies’ – areas of concentration of demographically small constituencies characterised by the lowest level of correspondence between their number of inhabitants and the uniform standard of representation – and clusters of large constituencies with the highest level of correspondence between their number of inhabitants and the uniform standard of representation;

(iii) arbitrary disparity between the average voting power of voters living in clusters of neighbouring constituencies located at opposite ends of a commune (e.g. the entire northern part of a commune, consisting of a number of ‘under-represented’ constituencies, and its southern part, consisting of a number of ‘over-represented’ constituencies).

Certain systemic consequences of the specific interpretation (endorsed by the Polish National Electoral Commission) of the provisions of the Election Code concerning the manner of applying the concept of uniform standard of representation in creating single-seat constituencies in villages, towns and small cities can be illustrated with the following simulation. The acknowledgement that, in the absence of established auxiliary units,Footnote 52 any division of a commune into single-seat constituencies with the number of inhabitants ranging from 0.50 to 1.49 of the uniform standard of representation is correct would entail recognition of the legitimacy of the following delineation/modification of boundaries of single-seat constituencies in a hypothetical town X:Footnote 53

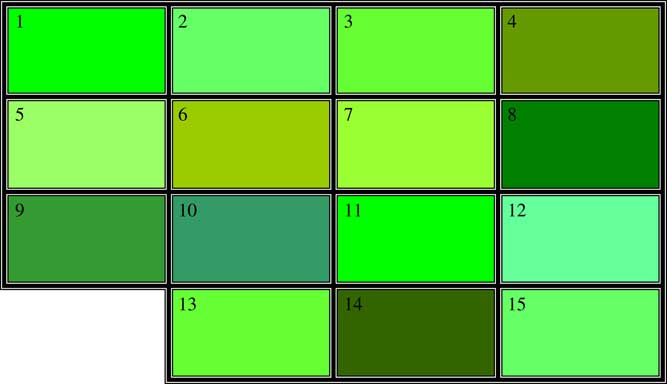

I. Initial situation: town X, having 15,000 inhabitants, without any established auxiliary units, characterised by the same population density over its entire area, dividable/divided into perfectly even, single-member constituencies with a number of inhabitants equal to the uniform standard of representation, i.e. 1,000. Figure 2 is a ‘map’ of town X showing the (possible) boundaries between the constituencies, and Table 1 shows the corresponding demographic data:

II. The situation after modification of the boundaries of all 15 constituencies in X – Figure 3 shows the new boundaries between the constituencies and their number of residents:

Figure 2 Possible (perfectly equal) division of town X into single-seat constituencies

Figure 3 Possible (maximally unequal) division of town X into single-seat constituencies

Table 1 Demographics behind single-seat constituencies in Figure 2

A cursory analysis of the two ‘maps’ shows that the new division of the town into 15 constituencies (similar to many other alternative configurations of identical nature) could be part of a completely natural course of events – it might be the result of an agreement between the councillors elected in constituencies 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 11. For seven of those councillors, the new division would mean a narrowing of their own constituencies by almost 50% (e.g. to the immediate vicinity of their place of residence); for one of them – the councillor elected in constituency 5 – the population of his/her constituency would remain unchanged in spite of a slight change of its boundaries. For all of these councillors – as well as for the inhabitants of their constituencies – it would be a fully rational decision, certainly resulting in a significant shift in local public expenditures towards investments in their parts of town: the councillors from constituencies 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 11 would have a majority on the 15-seat town council. It is not difficult to imagine a whole list of reasons ‘justifying’ this type of arrangement, e.g. ‘The need to strengthen the ties between the residents of the historical / central / higher (etc.) parts of the town’. Table 2 illustrates the basic electoral parameters of town X after the introduction of the changes:

Table 2 Demographics behind single-seat constituencies in Figure 3

As a result of such a division of town X into 15 constituencies, the resident-voters from constituencies 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 11, representing 24% of the total number of the town’s inhabitants (3,570 people) would have the same impact on the outcome of the elections as the resident-voters from constituencies 1, 4, 8, 12, 13, 14, and 15, representing 70% of the total number of the town’s inhabitants (10,430 people); each group would elect 7 councillors to the 15-seat council of town X. Thus, the voting power of resident-voters living in constituencies 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10 or 11 would be about 2.9 times greater than that of resident-voters living in constituencies 1, 4, 8, 12, 13, 14, or 15.

An additional factor increasing the severity of the above-described discrimination of the inhabitants of smaller constituencies is the durability of a commune council’s determination regarding the division of the commune into constituencies. In a recent decisionFootnote 54 concerning recently passed legislation requiring – in analogy to the Act of 5 January 2011Footnote 55 – that all commune councils divide their communes into constituencies within 60 days of the date the act came into force,Footnote 56 the National Electoral Commission referred to the principle of stability of the divisions of communes into constituencies,Footnote 57 stating that actual modification of these divisions is only possible under the conditions enumerated in Article 421 § 2 of the Election Code, i.e. only if ‘they are necessitated by changes in the territorial division of the state, changes in the boundaries of the auxiliary units of a commune, changes in the number of inhabitants of a commune, changes in the number of councillors electable to the commune council or changes in the number of councillors electable in any of the constituencies’.Footnote 58 What is more, in a number of individual resolutions concerning recent modifications of the boundaries between constituencies effected by certain commune councils, the National Electoral Commission expressed the opinion that even if the last of the above conditions is fulfilled, i.e. if the deviation from the standard of representation in a particular constituency were to exceed 50%, the commune council (from 1 January 2019 the relevant Electoral CommissionerFootnote 59 ) is only allowed to modify the boundaries of the constituency in question and – consequently – of the constituencies adjacent to it. In other words, even with the assent of all councillors – reached in view of a significantly disproportionate increase or decrease in the number of inhabitants of some of the largest or smallest single-seat constituencies respectively – to comprehensively re-adjust the division of their commune into constituencies and thus make it more proportionate (and more stable) as a whole, the commune council is forbidden from doing that – according to the National Electoral Commission – because of the importance of maintaining the stability of that division.Footnote 60

International standards of substantive equality of elections

Finally, it is important to point out the significant divergence between provisions of the Polish Election Code protecting the substantive equality of Polish local elections, and the common standards applicable in this field in most European countries. One should consider in this respect the status of recommendations defining the minimum conditions for the preservation of the substantive equality of elections formulated in the Code of Good Practice in Electoral Matters issued by the Venice Commission. Article 2.2, points 1-4, of this document state:

‘2.2. Equal voting power: seats must be evenly distributed between the constituencies.

i. This must at least apply to elections to lower houses of parliament and regional and local elections:

ii. It entails a clear and balanced distribution of seats among constituencies on the basis of one of the following allocation criteria: population, number of resident nationals (including minors), number of registered voters, and possibly the number of people actually voting. An appropriate combination of these criteria may be envisaged.

iii. The geographical criterion and administrative, or possibly even historical, boundaries may be taken into consideration.

iv. The permissible departure from the norm should not be more than 10%, and should certainly not exceed 15% except in special circumstances (protection of a concentrated minority, sparsely populated administrative entity)’.Footnote 61

It should certainly be noted that that the document prepared by the advisory body of the Council of Europe is not an international convention in the classic sense of the term.Footnote 62 In spite of this, a number of leading Polish legal scholars have argued that the recommendations of the Venice Commission should at the least be regarded as not indifferent to, if not fully binding with respect to, the creation of specific electoral regulations. An immediate opportunity to articulate such a conviction was presented by the debate on the verdict of the Constitutional Tribunal of 3 November 2006 concerning the constitutionality of changes introduced in the Act of 6 September 2006 to the Electoral Law to Councils of Communes, County Councils and Regional Councils (in force at the time). In justification of the ruling confirming the constitutionality of both the substance and the procedure of passing the Bill into law, the Tribunal stated that the recommendation, issued as part of a document that was not a classic international convention, could not constitute a conclusive presumption for the assessment of the conformity of a legislative procedure with the Polish Constitution. The Tribunal’s position was challenged in a dissenting opinion by Justice Marek Safjan. Although he shared the view of the majority of the panel on the specific status of the Code of Good Practice as falling short of the standard form of an international convention, he also stressed the need to respect the guidelines contained therein as important directives for the optimal model of electoral law in states that respect the principles of democracy and human rights. Considered in this way, the document of the Venice Commission should be read, in the opinion of Safjan, in connection with Article 9 of the Constitution; by joining the Council of Europe under an international treaty, Poland had ‘committed itself at least indirectly to respecting common ideals and principles constituting a common heritage [and] implemented through the organs of the Council of Europe (see Article 1 of the Statute) at least in terms of a certain legislative direction or legislative tendencies’.Footnote 63

A similar opinion was presented in a commentary on the Constitutional Tribunal’s ruling published by Masternak-Kubiak. According to her, the impact of soft law acts created by the Council of Europe, such as the Code of Good Practice in Electoral Matters, consists not so much in pointing out clear obligations incumbent on the Member States, but in presenting standards for assessment of the legitimacy of law-making, and in serving as a benchmark for the rightfulness of legislation. Although the document in question cannot be regarded as a separate source of international law, the basis for its significance is the Statute of the Council of Europe, ratified by Poland, and it should therefore be considered in the light of Article 9 of the Polish Constitution. Consequently, any derogation from the rules formulated therein should be interpreted as – in fact – a breach of binding international obligations.Footnote 64 A slightly less radical position, which in essence coincides with the opinion of Masternak-Kubiak, was presented by Ferdynand Rymarz (former Chairman of Poland’s National Electoral Commission). He does not see grounds for believing that the guidelines included in the Code of Good Practice are directly binding on state institutions, yet at the same time claims that ‘by virtue of their origin, and because of Poland’s membership in the Council of Europe as well as electoral standards acceptable in democratic states, they may not be indifferent from the point of view of the Polish constitutional principle of the democratic state ruled by law, under which these guidelines are strongly supported’.Footnote 65 Thus, the normative influence of the recommendations of the Venice Commission on the contours of the Polish electoral system is somewhat indirect, realised through the creation of a fundamental conceptual basis for the interpretation of Article 2 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland.

In the context of such opinions, the provisions of the Polish Election Code concerning the substantive equality of elections to councils of communes with a population equal to or smaller than 20,000 appear to be a completely arbitrary derogation from common understanding of one of the most fundamental concepts of constitutional law endorsed by the most authoritative international institution. It remains an open question as to why this situation has not yet raised any major concerns, or even aroused serious interest, from representatives of the Polish judiciary or political establishment.

Conclusion

In conclusion: the principle of substantive equality of elections, also referred to as ‘the principle of equal suffrage under its aspect of equal voting power’, is generally recognised as one of the essential foundations of genuinely fair electoral procedures. According to the recent report by the Venice Commission, equal voting power – ‘deeply interrelated with the more general principle of electoral representative democracy’ – constitutes ‘a crucial element of parliamentary democracy’, and must thus – also in local elections – be considered the underlying principle of the latter.Footnote 66 The practical guidelines concerning substantive equality issued by international bodies such as the Venice Commission, having, admittedly, only the status of soft law, should, nevertheless, be viewed as important determinants in specifying the basic rules for conducting democratic elections, also at the local level.

In the case of Poland, the principle in question, embedded in relevant provisions of the Polish Constitution, must be understood as a natural consequence of the constitutional guarantee of equality of citizens before the law (Article 32, Constitution of the Republic of Poland). This position is almost unanimously endorsed by Polish legal scholars, who generally accept that ‘the principle of equality of elections is a concretisation within the framework of electoral law of the principle of equality of citizens in all spheres of life’.Footnote 67 Yet, with the specific content of the provisions of the Election Code concerning the application of the uniform standard of representation in the creation of constituencies in communes with a population equal to or smaller than 20,000, the principle of substantive equality of elections does not in actual practice apply in such communes. The single-seat constituencies created in certain communes by their respective commune councils can, and in 51% of those communes actually do, differFootnote 68 in terms of number of residents by a factor of between 2 and 3. Such differences contribute significantly to the emergence of serious inequality between residents of the same commune in their ability to influence the policies of local self-government.

The passage of the abovementioned legislation containing a number of amendments to the Polish Election CodeFootnote 69 created an opportunity to ameliorate the substantive equality standards of Polish local elections. The originally proposed version of the Act of 11 January 2018 – aimed at modifying the Election Code ahead of local elections scheduled for the autumn of 2018 – was supposed to completely eliminate the first-past-the-post system from local elections and replace it with a proportional system based on 5-to-8-seat constituencies. In view of the above analysis, such a change would have automatically fixed the problem of affording adequate statutory protection to the substantive equality of local elections. At the same time, it would have brought an abrupt end to an almost 30-year-old tradition of single-seat constituencies used for these types of elections. After having been heavily criticised by both the opposition parties and the representatives of local authorities, the ruling majority decided to leave the general system unchanged, while narrowing the scope of application of the first-past-the-post system: from all communes which are not cities with county rights (2,412 out of a total of 2,478 communes in Poland) to communes with a population equal to or less than 20,000 (2,136 communes).

Because of the exceptionally close ties they generate between the voters and their elected representatives, single-seat constituencies seem to be a perfect fit for legitimising democratic power structures at their most basic level. To complete the types of task faced by local government, direct communication with the electorate is crucial, and such channels are effectively guaranteed by the first-past-the-post voting system. However, to ensure an at least minimally fair distribution of the electorate’s impact on the policy of local authorities, one has to devise an effective method of protecting the substantive equality of election procedures. The standards of substantive equality proposed in the Electoral Law of 1990, i.e. the maximum allowable deviation from the standard of representation of 20%, constitute the toughest possible compromise with the demands of political pragmatism – even if administrative, geographical, historical, or ethnic loyalty ties between voters are taken into consideration. It must be stressed, however, that the specific understanding of the principle of substantive equality of elections, which paved the way for acceptance of the current consequences of Article 419 § 2 of the Election Code, contradicts one of the most fundamental assumptions of the law-making process, i.e. the assumption of rationality on the part of the legislator. It remains to be seen whether, and must be hoped that, the problems concerning elections required by the Polish Constitution to be equal elections will quickly find an adequate legislative resolution.