Article contents

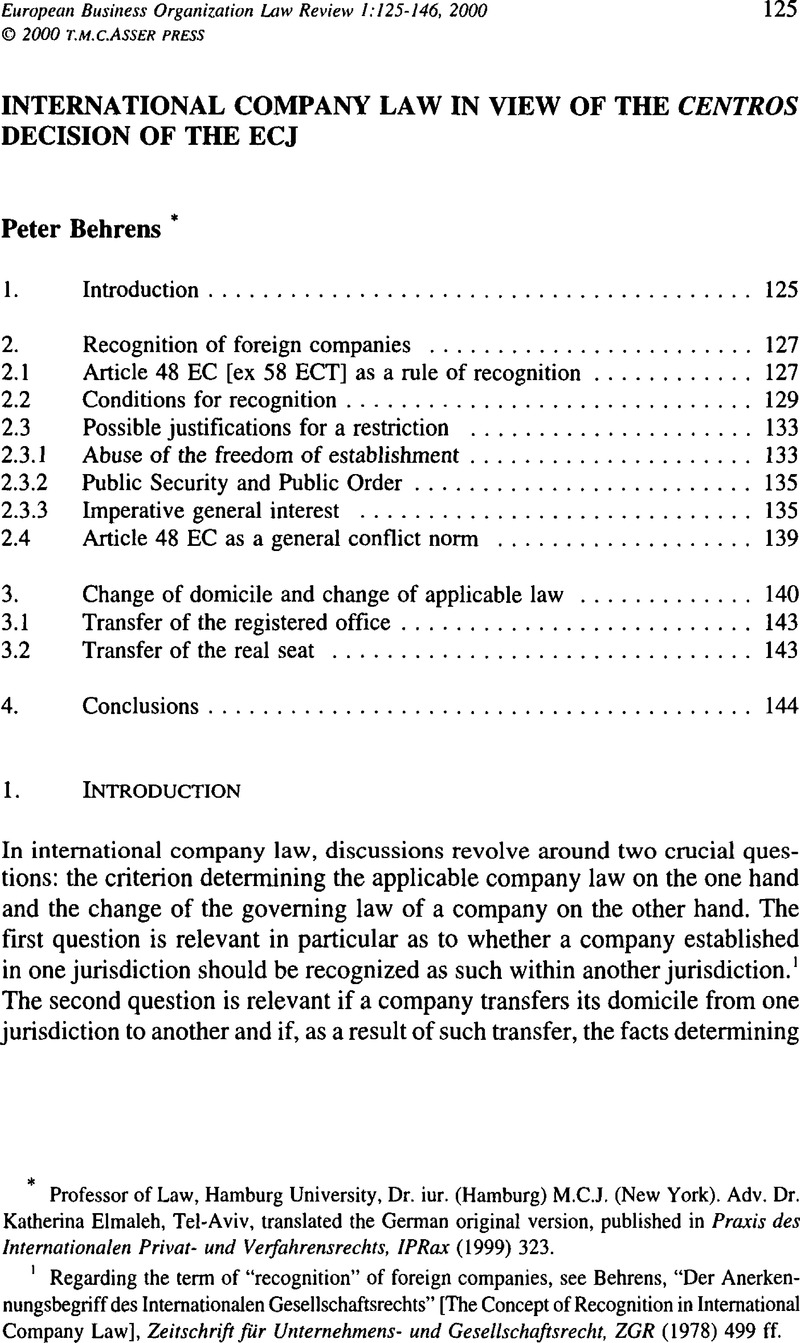

International Company Law in View of the Centros decision of the ECJ

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 17 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Case Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © T.M.C. Asser Press and the Authors 2000

References

1 Regarding the term of “recognition” of foreign companies, see Behrens, , “Der Anerken-nungsbegriff des Internationalen Gesellschaftsrechts” [The Concept of Recognition in International Company Law], Zeitschrift für Unternehmens- und Gesellschaftsrecht, ZGR (1978) 499 ff.Google Scholar

2 On questions relating to a company's transfer of domicile, see Behrens, , Die Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung im internationalen und europäischen Recht [The GmbH in International and European Law], 2nd edn. (1997)Google Scholar, Abschnitt: Internationales Gesellschaftsrecht und Fremden-recht [Section: International Company Law and Foreign Law], para. IPR 61 ff. with further references.

3 See Behrens, , “Niederlassungsfreiheit und internationales Gesellschaftsrecht” [Freedom of Establishment and International Company Law], 52 Rabels Zeitschrift (1988) 498 ff.Google Scholar; idem, “Die Umstrukturierung von Unternehmen durch Sitzverlegung oder Fusion über die Grenze im Licht der Niederlassungsfreiheit im Europäischen Binnenmarkt (Art. 52 und 58 EWGV)”, [The Reorganization of Enterprises by a Cross-Border Transfer of Domicile or International Merger in the Light of the Freedom of Establishment, Arts. 52 and 58 ECT], ZGR (1994) 1 ff.Google Scholar; see in particular the extensive survey by Brodermann in Brödermann and Iversen, Europäisches Gemeinschaftsrecht und Internationales Privatrecht (European Community Law and Private International Law), 57 Beiträge zum ausländischen und internationalen Privatrecht (1994), pp. 60 ff. at para. 96 ff.

4 C-81/87 The Queen v. Daily Mail and General Trust PLC, [1988] ECR 5483 = IPRax (1989) 381 ff.

5 See hereto critically Behrens, , “Die grenzüberschreitende Sitzverlegung von Gesellschaften in der EWG” [The Cross-Border Transfer of Company Domicile within the EEC], IPRax (1989) 354 at 359.Google Scholar

6 IPRax (1999) 364, n. 40.

7 C-212/97 Centros Ltd. v. Erhvervs- og Selskabssyrelsen, [1999] ECR I-1459.

8 Generally, a company may be established exclusively by registering as prescribed by law. Such registration is usually made only at the company's registered office as specified in its statutes. Consequently, the incorporation theory leads to the application of the laws of the company's registered office.

9 See hereto Behrens, op. cit. n. 2, para. IPR 3 ff. and Staudinger (-Großfeld), Internationales Gesellschaftsrecht [International Company Law] (1998), para. 26 ff.

10 Zimmer, , Internationales Gesellschaftsrecht [International Company Law] (1996) p. 233Google Scholar; see also the review hereto by Behrens, , 63 Rabels Zeitschrift (1999) 391 ff.Google Scholar

11 See the convincing explanations in Brödermann, supra n. 3, pp. 78 ff, para. 126 ff.

12 Since 1986, the direct applicability of Article 58 ECT [now Article 48 EC] has been repeatedly confirmed by the ECJ: C-270/83 Commission v. French Republic, [1986] ECR 273 at 304, recital 18; C-79/85 Segers v. Bestuur van de Bedrijfsvereniging voor Bank- en Ver-zekeringswezen, Groothandel en Vrije Beroepen, [1986] ECR 2375 at 2387, recitals 12-14 and 16; particularly clearly the Daily Mail decision, supra n. 4, recital 15.

13 This priority of Article 48 EC follows from the general principles of Community law as developed by the ECJ.

14 In the past: Wiedemann, , Gesellschaftsrecht I: Grundlagen [Company Law I: Principles] (1980), 793–794Google Scholar and Staudinger (-Großfeld), Internationales Gesellschaftsrecht (10th/11th edn. 1981) para. 92; see now for the opposite view Staudinger (-Großfeld), supra n. 9, para. 120.

15 Critically BayObLG (Bayerisches Oberlandesgericht) 21 March 1986, BayObLGZ 1986, 61at 73 = Neue Juristische Wochenschrift, NJW (1986) 3029 at 3032; BayObLG 18 September 1986, BayObLGZ 1986, 351 at 359-360 = Recht der internationalen Wirschaft (Zeitschrift), RIW (1987) 52 at 54; sceptical even after the Daily Mail decision is Ebke, , “Die ‘ausländische Kapital-gesellschaft & Co. KG’ und das Europäische Gemeinschaftsrecht” [The Limited Partnership with a Foreign Company Limited by Shares as General Partner under European Community Law], ZGR (1987) 245 at 250.Google Scholar

16 In the past: Wiedemann and Staudinger (-Großfeld), supra n. 14; Ebke, supra n. 15.

17 See supra n. 6.

18 Explicitly Drobing, “Gemeinschaftsrecht und internationales Gesellschaftsrecht – ‘Daily Mail’ und die Folgen” [Community Law and International Company Law – Daily Mail and its consequences], in: von Bar, (ed.), Europäisches Gemeinschaftsrecht und Internationales Privatrecht [European Community Law and Private International Law] (1991) pp. 185 ff., 190.Google Scholar

19 This must be strictly separated from the additional condition that an agency, branch or subsidiary must be “established” within the Community in the sense of Art. 43 para. 1, 2nd sentence EC [ex Art. 52 para. 1, 2nd sentence ECT]. See hereto infra n. 26.

20 See supra n. 8.

21 See Behrens, supra n. 1.

22 See also in detail most recently Brödermann, supra n. 3, pp. 81 ff., para. 133 ff.

23 See supra n. 12.

24 Zimmer, op. cit. n. 10.

25 To the fact that the reference in Article 48 EC is limited to the substantive laws of the state of establishment and, therefore, does not include the conflict rules, see Brödermann, supra n. 3, pp. 75 ff., para. 121 ff.

26 See the ECJ decisions cited supra n. 12.

27 Such discrimination was discussed in the decisions cited supra n. 12.

28 See Daily Mail decision, supra n. 4, recital 21.

29 See the EEC Council in Title I of its General Programmes for the Abolition of Restrictions to the Freedom of Services and to the Freedom of Establishment, both of 18 December 1962, OJ English Special Edition (2nd Series) IX, p. 3 (services) and p. 7 (establishment).

30 C-33/74 Van Binsbergen, [1974] ECR 1299, recital 13.

31 C-206/94 Paletta, [1996] ECR I-2357, recital 24.

32 According to this theory, pseudo-foreign companies without any cross-border relations except their foreign law of incorporation should be judged exclusively under domestic law, see supra n. 10.

33 EEC Rome Convention on the Law Applicable to Contractual Obligations of June 19,1980, OJ [1980] L 266/1 = 19 ILM (1980) 1492.

34 See hereto Brödermann, supra n. 3, pp. 151 ff., para. 274 ff.

35 This has clearly been stated in the decisions referred to in the Centros decision: C-19/92 Kraus, [1993] ECR 1-1663, recital 32 and C-55/94 Gebhardt, [1995] ECR 1-4165, recital 37.

36 “If the business of a company formed under foreign law is conducted in or from Switzerland, the liability of the persons acting on behalf of the company shall be governed by Swiss law.” Regarding the exception from the general applicability of the law of incorporation by favouring the domestic law of seat, see the supporters of a “restricted theory of incorporation”; Behrens, op. cit. n. 2, para. IPR 23; sceptical hereto see Zimmer, op. cit. n. 10, p. 215.

37 Bull. EC Suppl. 2/69.

38 See supra n. 6.

39 Similarly already BayObLG 7 May 1992, BayObLGZ 1992, 113 at 115 = Europäische Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsrecht, EuZW (1992) 548Google Scholar with comments by Behrens.

40 Critical in this context Behrens, supra n. 3, 512.

41 Extensively hereto Zimmer, op. cit. n. 10, pp. 241 ff.

42 See hereto idem pp. 327 ff.

43 Correctly idem pp. 327 ff.

44 Idem, pp. 387 ff.

45 Eidenmüller, and Rehm, , “Gesellschafts- und zivilrechtliche Folgeprobleme der Sitztheorie” [Company and Private Law Problems Resulting from the Real Seat Theory], ZGR (1997) 89–114.Google Scholar

46 This has been repeatedly emphasized by Zimmer, op. cit. n. 10, e.g., on p. 188.

47 See supra n. 6.

48 On the conflict rules of liability see Behrens, , “Der Durchgriff über die Grenze” [Piercing the Corporate Veil across National Borders], 46 Rabels Zeitschrift (1982) 308 at 331ff.Google Scholar

49 Hereto already Behrens, supra n. 3, at 518.

50 See hereto Behrens, , “Identitütswahrende Sitzverlegung einer Kapitalgesellschaft von Luxemburg in die Bundesrepublik Deutschland” [The Transfer of Domicile from Luxembourg to Germany Without Destroying the Legal Personality of the Company], RIW (1986) 590 ffGoogle Scholar; idem ZGR (1994), supra n. 3,1 at 24; K., Schmidt, “Sitzverlegungsrichtlinie, Freizügigkeit und Gesell-schaftsrechtspraxis” [The Directive on the Transfer of Domicile, Freedom of Movement and Company Law Practice], ZGR (1999) 20 at 22 ff.Google Scholar

51 Regarding this characterization see Behrens, supra n. 50.

52 The draft, issued by the Commission, was published in Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsrecht, ZIP (1997) 1721 ff.Google Scholar (Doc. XV/D2/6002/97-REV02, 5 March 1998); see also K. Schmidt, supra n. 50.

53 On completion of this study (July 1999) the following reviews were published on the decision: G.H., Roth, “Gründungstheorie: ist der Damm gebrochen?” [Theory of incorporation: a breakthrough?], ZIP (1999) 861 ff.Google Scholar; Werlauff, , “Ausländische Gesellschaft, inländische Aktivität” [Foreign Company, Domestic Activities], ZIP (1999) 867 ff.Google Scholar; Freitag, , “Der Wettbewerb der Rechtsordnungen im Internationalen Gesellschaftsrecht” [Competition of Legal Systems in International Company Law], EuZW (1999) 267 ff.Google Scholar; Höfling, , “Die Centros-Entscheidung des EuGH – auf dem Weg zu einer Überlagerungstheorie für Europa” [The Centros Decision of the ECJ – on the Way to an Overlapping Theory for Europe], DB (1999) 1206 ff.Google Scholar; Ebke, , “Das Schicksal der Sitztheorie nach dem Centros-Urteil des EuGH” [The Fate of the Theory of Domicile after the Centros Decision of the ECJ], JZ (1999) 656 ff.Google Scholar; Ulmer, , “Schutzinstrumente gegen die Gefahren aus der Geschäftstätigkeit inländischer Zweigniederlassungen von Kapital-gesellschaften mit fiktivem Auslandssitz” [Instruments of Protection against the Dangers Imminent in Doing Business with Domestic Branches of Companies with a Fictitious Foreign Seat], JZ (1999) 662 ff.Google Scholar; Kindler, , “Niederlassungsfreiheit für Scheinauslandsgesellschaften? – Die Centros-Entscheidung des EuGH und das internationale Privatrecht” [Freedom of Establishment for Pseudo Foreign Companies? – The Centros Decision of the ECJ and Private International Law], NJW (1999) 2064 ff.Google Scholar; see also the following short comments: Leible, , Neue Zeitschrift für Gesellschaftsrecht, NZG (1999) 300 ff.Google Scholar; Neye, , Entscheidungen zum Wirtschaftsrecht, EwiR (1999) 259Google Scholar; Meilicke, , DerBetrieb (Zeitschrift) DB (1999) 625 ff.Google Scholar; Sedemund, and Hausmann, , Betriebs-Berater, BB (1999) 810.Google Scholar

- 5

- Cited by