An artist's biography, and the personal circumstances under which an artwork is made, can add to our understanding of his or her work. Biography should not be our first concern as we view an artwork, but can play an important role in our full understanding of an artist's work.

There are infinite possibilities to what a painting can look like. In the paintings of William Scott (b. 1964), we see self-portraits, cityscapes, buildings and pictures of imaginary friends. Aesthetically, these works have compelling associations with photorealistic paintings, West African signage, and architectural studies. Yet the content of these works depict an altered reality that at first may not be immediately understood. Together, these images depict a utopian world filled with renewed urban structures, revised personal histories and the rebirth of entire cities and their citizens.

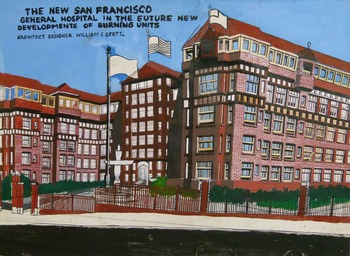

There is evidence of artists with autism having the capacity to study and store visual detail and to call forth these memorised elements in their work (Cardinal, Reference Cardinal2009). William Scott is such an artist. His architectural depictions of skyscrapers, hospitals and urban landscapes are drafted from memory, often with acute attention to detail and mapping (Figs 1 and 2).

William's vision of the future, and his talent as an artist, are influenced by his dual diagnosis. Living on the autistic spectrum, and with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, William has developed a style of work that incorporates both his outstanding attention to detail, and his belief in a fantasied utopian reality.

Fig. 1. William Scott, Untitled (Billy the Kid), 2010, Acrylic on paper, 18 × 24 inches. Collection of Sophie Berdah.

Fig. 2. William Scott, Untitled (The New San Francisco), 2004, Acrylic and ink on paper, 22 × 30 inches. Collection of Mitzi Johnson.

As a child with disabilities growing up in an often violent and economically poor neighbourhood in San Francisco, William was exposed to random street violence, scenes of poverty and neglected urban housing projects. Seeking to rise above these circumstances, he assigned himself a herculean task: to paint away these injustices, and to craft a new order of wholesome positive people living in a renewed and positive world.

With the support of a local librarian, Scott made his way to the Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland, California, a noted centre for artists with disabilities. Working there for over 25 years, his painting technique and his path towards fantasy increased. ‘The distance between what Scott believes and imagines and what the audience responds to are different, reflecting the difference between the painting being a kind of time machine to alter reality and a mere depiction of an imaginary new work’ (Trainor, Reference Trainor2006).

As an example, in a self-portrait, Scott depicts himself in 1977 as ‘Billy the Kid.’ Using the painting as a vehicle to travel back to his childhood, he imagines his young self as happy, successful at basketball, popular and without disabilities. The painting becomes a transformative tool, one that reinvents the past with the hope that it will turn his current reality into the life he fully desires.

His memory painting of San Francisco General Hospital is not merely a startling image constructed from recollection, but also a time machine designed to transport Scott back to the moments before an accident sent him to the hospital's burn unit. Preoccupied by the permanent scar left on his body from the incident, he attempts to paint away the accident itself by going back in time and erasing it from his personal history.

Most striking are Scott's space ships that fly under the banner of ‘Inner Limits.’ The glowing faces of young African-American men and women who seem to have just stepped from the craft surround these vessels. What we are witnessing is their rebirth. These are people that William cares for, those killed by drugs and street violence. His spaceship is the vehicle for bringing those taken from this world back to us for a second life filled with hope and a new reality.

In the exhibition called Alternative Guide to the Universe, at the Hayward Gallery in London, Ralph Rugoff presented artists whose work seeks to change reality. Scott was in good company with others whose numbering systems, scientific investigations and fantasied realties teetered on the edge of invented new worlds. There, Scott's work ‘invites us to think outside of our conventional categories and ultimately to question our definitions of ‘normal’ art and science’ (Rugoff, Reference Rugoff2013).

One must ask if Scott's paintings fulfil the hope of the artist, if they do in fact change the reality in which he lives. Scott often struggles with reality not changing in accordance with his paintings. Sparkling new housing projects have not been built; those tragically killed from random violence have not come back to life. However, his art has indeed changed his life. From his early years as a child with disabilities in an under-privileged environment, to an adult whose work has now been acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Studio Museum of Harlem, one can argue that his method of transforming reality into a more vibrant and wholesome encounter with the world seems to be working.

About the author

Tom di Maria is Director of the Creative Growth Art Center, Oakland, California since 2000. Creative Growth was founded in the early 1970s and is the world's oldest and largest art center for people with disabilities in the USA. Today the centre serves over 150 artists with developmental disabilities every week in its spacious art studio and gallery. Under di Maria's administration Creative Growth gained a high-visibility position in the Contemporary Art scene and an impressive market success. Art pieces from Creative Growth are displayed at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; at the Oakland Museum of California; at the Museum of Modern Art, New York; and were recently acquired by Facebook, Christie's and the Smithsonian. Prior to pushing the boundaries from Outsider Art into Contemporary Art, di Maria was Assistant Director of the Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive at UC Berkeley and Executive Director of GLAAD/San Francisco, and Director the San Francisco International Lesbian & Gay Film Festival. He recently released the new publication The Creative Growth Book (5 Continents Press) and speaks around the world on Creative Growth's artists and programmes.