Introduction

Suicide, the intentional ending of a person's own life, accounts for approximately 817 000 deaths and 2.2% of all years of life lost worldwide annually (Naghavi and Global Burden of Disease Self-Harm Collaborators, Reference Naghavi2019). Self-harm is a broader concept, which encompasses degrees of intentionality that are hard to separate: from attempted suicide (which the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates dwarfs death by suicide by at least 20-fold) to non-suicidal self-injury (Gvion and Apter, Reference Gvion and Apter2012; World Health Organization, 2014). Thoughts of suicide is also a complex area and these are sometimes considered in terms of active thoughts of suicide (considering intentionally ending one's life) and passive thoughts of suicide (thoughts about not wishing to live any longer) (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Kovacs and Weissman1979). The epidemiology of suicide and self-harm show marked differences in terms of age, gender and culture (Skegg, Reference Skegg2005; Colucci and Martin, Reference Colucci and Martin2007; Angst et al., Reference Angst, Hengartner, Rogers, Schnyder, Steinhausen, Ajdacic-Gross and Rössler2014; Fazel and Runeson, Reference Fazel and Runeson2020).

An epidemic occurs when a disease significantly exceeds the expected number of cases in a given population. A pandemic is an epidemic that occurs over multiple countries or continents (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). Infectious epidemics can be caused by a large range of pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, parasites and prions (‘WHO | Disease Outbreaks by Year’ (WHO, 2020)). The current COVID-19 pandemic is caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus and has spread with unprecedented speed, resulting in intense speculation as to its effects on physical and mental health (Douglas et al., Reference Douglas, Katikireddi, Taulbut, McKee and McCartney2020; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, O'Connor, Perry, Tracey, Wessely, Arseneault, Ballard, Christensen, Cohen Silver, Everall, Ford, John, Kabir, King, Madan, Michie, Przybylski, Shafran, Sweeney, Worthman, Yardley, Cowan, Cope, Hotopf and Bullmore2020; Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Chesney, Oliver, Pollak, McGuire, Fusar-Poli, Zandi, Lewis and David2020; Wang and Tang, Reference Wang and Tang2020).

Disasters and existential threats may result in higher rates of suicide and there was some evidence that suicide rates increased during the 2008 financial crisis in Europe (Parmar et al., Reference Parmar, Stavropoulou and Ioannidis2016). However, this is not automatic and rates may even fall, perhaps due to increased social cohesion (Lester, Reference Lester1994; Claassen et al., Reference Claassen, Carmody, Stewart, Bossarte, Larkin, Woodward and Trivedi2010), as postulated by Durkheim in the 19th century (Durkheim, Reference Durkheim1897). There is a reason for concern about the impact of infectious outbreaks on the frequency of suicide and self-harm. Possible reasons for an increase include fear of infection, the stigma for those infected, pressure on health care systems – with a detrimental impact on health care workers – financial pressures, unemployment, social isolation, increased stress on intimate relationships, increasing access to lethal means, worsening substance misuse and media alarmism (Aquila et al., Reference Aquila, Sacco, Ricci, Gratteri, Montebianco Abenavoli, Oliva and Ricci2020a, Reference Aquila, Sacco, Ricci, Gratteri and Ricci2020b; Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Brambilla and Solmi2020; Kawohl and Nordt, Reference Kawohl and Nordt2020; Moutier, Reference Moutier2020; Reger et al., Reference Reger, Stanley and Joiner2020; Salazar de Pablo et al., Reference Salazar de Pablo, Vaquerizo-Serrano, Catalan, Arango, Moreno, Ferre, Shin, Sullivan, Brondino, Solmi and Fusar-Poli2020; Wasserman et al., Reference Wasserman, Iosue, Wuestefeld and Carli2020). Concerns have also been raised about the particular impact on certain groups, namely those actually infected (Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Chesney, Oliver, Pollak, McGuire, Fusar-Poli, Zandi, Lewis and David2020), health care workers (Aquila et al., Reference Aquila, Sacco, Ricci, Gratteri, Montebianco Abenavoli, Oliva and Ricci2020a; Reger et al., Reference Reger, Stanley and Joiner2020; Salazar de Pablo et al., Reference Salazar de Pablo, Vaquerizo-Serrano, Catalan, Arango, Moreno, Ferre, Shin, Sullivan, Brondino, Solmi and Fusar-Poli2020), those with pre-existing psychiatric illness (Gunnell et al., Reference Gunnell, Appleby, Arensman, Hawton, John, Kapur, Khan, O'Connor and Pirkis2020) and the elderly (Aquila et al., Reference Aquila, Sacco, Ricci, Gratteri, Montebianco Abenavoli, Oliva and Ricci2020a). Case series of suicides that are apparently related to the COVID-19 pandemic have emerged from India, Germany and Pakistan, highlighting issues of pre-existing mental health problems, fear of the pandemic, financial and occupational problems, loneliness, stigma related to infection and alcohol withdrawal (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Khaium and Tazmeem2020; Buschmann and Tsokos, Reference Buschmann and Tsokos2020; Dsouza et al., Reference Dsouza, Quadros, Hyderabadwala and Mamun2020; Mamun and Ullah, Reference Mamun and Ullah2020; Rajkumar, Reference Rajkumar2020; Shoib et al., Reference Shoib, Nagendrappa, Grigo, Rehman and Ransing2020; Syed and Griffiths, Reference Syed and Griffiths2020).

The International Association for Suicide Prevention has noted the paucity of data on the effects of the current pandemic on suicide and has issued an urgent call for further evidence on the subject (IASP Executive Committee, 2020). One systematic review examined the psychological experience of survivors of Ebola virus disease and reported a high frequency of thoughts of suicide in a small population (Keita et al., Reference Keita, Taverne, Sy Savané, March, Doukoure, Sow, Touré, Etard, Barry and Delaporte2017; James et al., Reference James, Wardle, Steel and Adams2019). A recently published review examined suicide in viral epidemics, but articles published after 7 April 2020 were excluded, so it does not consider evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic (Leaune et al., Reference Leaune, Samuel, Oh, Poulet and Brunelin2020). Another review including articles up to May 2020 was also unable to include any peer-reviewed studies on COVID-19 and did not conduct any meta-analysis (Zortea et al., Reference Zortea, Brenna, Joyce, McClelland, Tippett, Tran, Arensman, Corcoran, Hatcher, Heise, Links, O'Connor, Edgar, Cha, Guaiana, Williamson, Sinyor and Platt2020). To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive review of suicide and self-harm in infectious epidemics and the first to include substantial data on the COVID-19 pandemic.

This review aimed to assess the impact of infectious epidemics on individuals in the geographical area of the epidemic (whether or not they were infected) in terms of actual cases of suicide, self-harm, and thoughts of suicide or self-harm, both during the epidemic and in the subsequent two-year period, during which time the effects may still be felt economically and socially. We also aimed to identify any risk factors that would highlight especially vulnerable groups.

Method

Objectives

We aimed to establish whether – during an infectious epidemic – there is a change in rates of (a) death by suicide, (b) self-harm, and (c) thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The population was people in a region where an infectious epidemic took place. The comparison groups (where available) were either the same population during a different time period or a different population during the same time period. Our primary outcome was the change in death by suicide; secondary outcomes were self-harm and thoughts of suicide or self-harm. An additional objective was to establish the frequency of these three outcomes during an infectious epidemic. We initially intended to meta-analyse the incidences of these outcomes, but, while incidences for death by suicide were available, the other outcomes were generally reported in terms of period prevalences. In such cases, meta-analysis of period prevalence was completed instead. Studies were included if they reported original research published in peer-reviewed journals and they described randomised controlled trials, cohort studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional surveys or ecological studies.

We included studies that reported suicide, suicide attempts, non-suicidal self-injury, thoughts of suicide and thoughts of self-harm, either self-reported or elicited by a clinician. However, many studies did not distinguish between these outcomes. Specifically, suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury were not always distinguished, and thoughts of suicide and thoughts of self-harm were not always distinguished (often because studies used a measure, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) that includes both symptoms in a single question). We, therefore, reported our outcomes in three groups: (a) death by suicide, (b) self-harm (including suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury) and (c) thoughts of suicide or self-harm. We also included studies that examined internet search trends for suicide-related terms, as a proxy measure for thoughts of suicide.

Search strategy and selection criteria

This systematic review followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, as shown in the online Supplementary material (pp. 2–5). The study review protocol was pre-registered on the PROSPERO database and is available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020193926.

We included original studies that reported suicide, suicide attempts, actual self-harm, thoughts of suicide, or thoughts of self-harm among populations where an infectious epidemic had occurred, either during or in the two years following the epidemic. We examined for control groups that were either the same population during a different time period or a different population during the same time period. We did, however, include studies that lacked control groups, as they have value in calculating pooled prevalences. There were no exclusions based on language; where a paper was not in English, screening and data extraction were conducted in consultation with a co-author who was a native speaker of that language. In order to enable us to observe the relationship between exposure and outcomes, we made a pragmatic decision to exclude epidemics (such as HIV) that lasted longer than three years and events recorded more than two years after the end of an epidemic.

We used OVID to search MEDLINE (and Epub ahead of print, in-process and other non-indexed citations, Daily and Versions(R)), Embase (Classic + Embase), APA PsycINFO and AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine) from inception until 24 June 2020; the search was subsequently updated to 9 September 2020. The overall search strategy was to combine epidemic AND infection AND (suicide OR self-harm), along with the comprehensive use of synonyms and subject headings to search within titles, abstracts and keywords without limits. The entire search strategy is in the online Supplementary material (pp. 9–16). In addition, we searched the reference lists of other relevant papers, examined the references from a related live systematic review (https://f1000research.com/articles/9-1097) and contacted experts in the field to identify unpublished data.

De-duplication was conducted manually by one reviewer (NB) in consultation with a second (JPR). Two reviewers (JPR and EC) screened titles, abstracts and full texts of extracted articles sequentially. Where there was disagreement on the inclusion of a title or abstract, it was retained for the next round of screening. Where there was disagreement on the inclusion of a full text, it was discussed with a third reviewer (DO). Reasons for exclusion of full texts were recorded.

Data extraction

Data extraction included the citation, geographical region, infection, date of the epidemic, study design, data collection method, population, control group, number of cases, number of controls, age, gender, time period, outcomes reported, and number of individuals with each outcome. Data for each paper were independently extracted by two of the authors (EC, NB, AS and JPR). Where reviewers disagreed, a third author (JPR or EC) arbitrated. Where there were missing data, investigators were contacted with a request to provide these data.

Data analysis

A systematic review of the literature was conducted, summarising results with one table for each of the three specified outcomes. The meta-analysis was also planned for each of these outcomes if at least five studies with relevant data were available. Studies were included in meta-analyses where there was the systematic assessment of outcomes for every individual. A random-effects model was employed because high heterogeneity was expected. A logit transformation was used to better approximate a normal distribution, as required by the assumptions of conventional meta-analysis models. Following the analysis, the synthesised result was back-transformed for ease of interpretation. The effect size measure for death by suicide was incidence; the effect size measure for self-harm or thoughts of suicide or self-harm was period prevalence. Period prevalences were defined as the proportion of cases over the sample size during the stated period (Barendregt et al., Reference Barendregt, Doi, Lee, Norman and Vos2013). If data from multiple populations (e.g. patients and healthy controls) were reported, these were considered as separate estimates of period prevalence in the analysis. Due to a lack of studies presenting data from a control group, we were unable to assess change in incidence or prevalence in the meta-analysis. Subgroup analysis was planned by geographical region, specific disease epidemic, age group, gender, outcome operationalisation (thoughts of self-harm v. thoughts of suicide) and presence of pre-existing mental disorder. Actual subgroup analysis was performed for age group (children and adolescents), pre-existing mental disorder, infection status, health care worker status and phase of the epidemic (intra-epidemic v. post-epidemic) with a meta-regression for outcome operationalisation. I 2 was calculated as a measure of between-study heterogeneity. Funnel plot asymmetry was not assessed as meta-analysis was used to calculate pooled prevalence, which is not characterised by the potential for negative or undesirable results that could have biased publication (Sterne et al., Reference Sterne, Sutton, Ioannidis, Terrin, Jones, Lau, Carpenter, Rücker, Harbord, Schmid, Tetzlaff, Deeks, Peters, Macaskill, Schwarzer, Duval, Altman, Moher and Higgins2011). To assess the robustness of the results, we performed sensitivity analyses by sequentially removing each study and re-running the analysis. We also performed a sensitivity analysis by study quality. Meta-regressions to investigate the impact of the type of assessment (thoughts of suicide plus thoughts of self-harm v. thoughts of suicide alone) were conducted on a subgroup level if more than ten studies reported relevant data on the same outcome. Data were analysed using R version 3.3.2 and the meta-package version 4.11. The threshold for two-tailed statistical significance was set to p < 0.05.

Assessment of quality and risk of bias were performed at the study level using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (Wells et al., Reference Wells, Shea, O'Connell and Peterson2000). Studies scoring 0–3 point were deemed to be of low quality, those scoring 4–6 were of moderate quality and those scoring 7–9 were of high quality.

Results

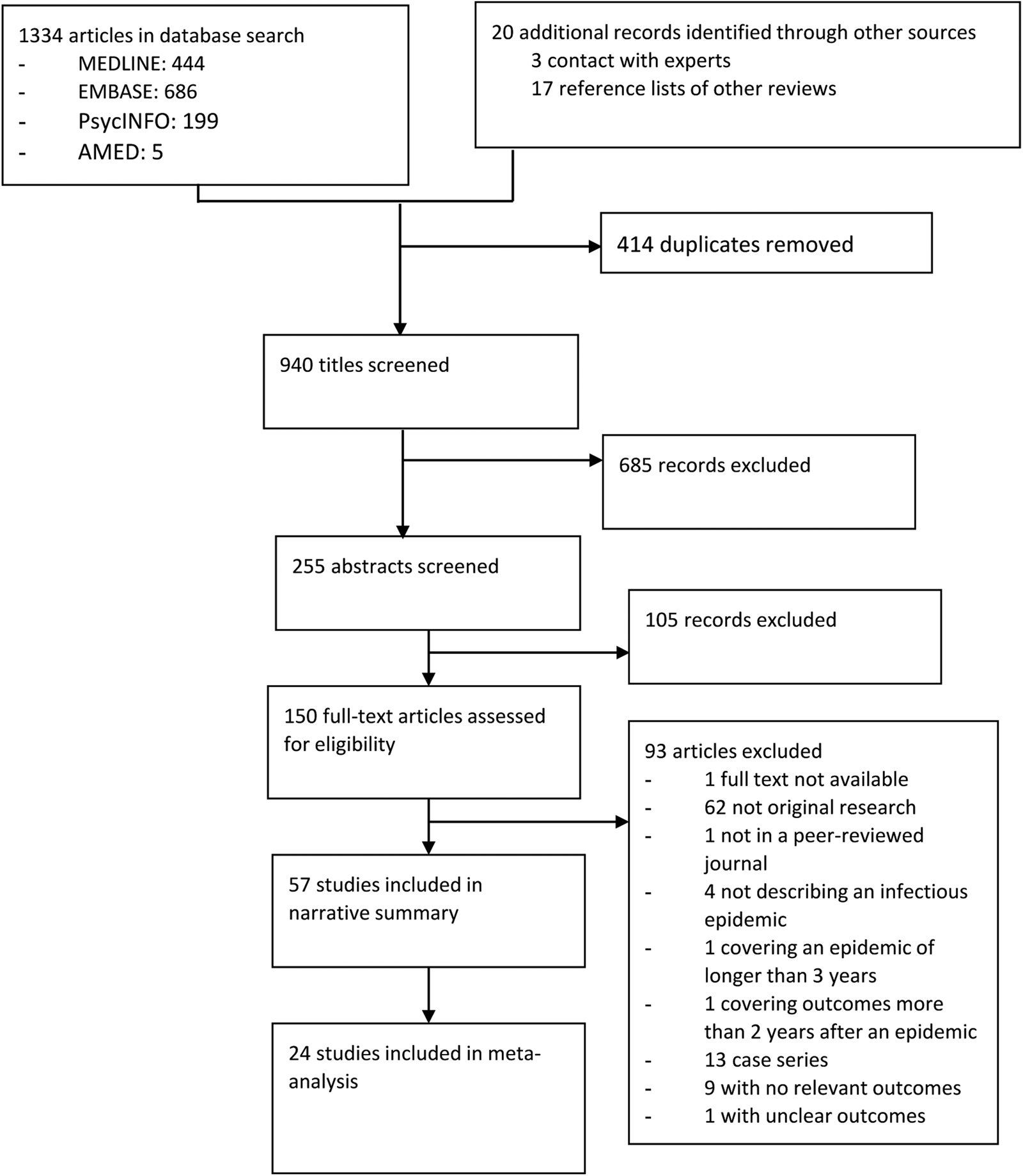

In total, 1354 articles were screened with 57 meeting eligibility criteria, as shown in Fig. 1, 32 of which were added after the literature search was re-run 77 days later. Seven studies described suicide, 9 self-harm and 45 thoughts of suicide or self-harm (some studies reporting more than one relevant outcome). Sample size ranged between 21 and ~87 000 000. The mean age of the samples, where reported, ranged from 19.9 years [standard deviation (s.d.) 1.6] to 74.9 years (s.d., 5.7). The date of study period ranged from 1910 to 2020 and included the following epidemics: Spanish flu (USA, 1918–1920) (one study), severe acute respiratory syndrome (Hong Kong and Taiwan, 2003) (five studies), human monkeypox (Nigeria, 2017) (one study), Ebola virus disease (Guinea, Uganda and Sierra Leone, 2000–2016) (four studies) and COVID-19 (Australia, Bangladesh, China, Denmark, France, Greece, India, Iran, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, UK, USA and worldwide, 2019–2020) (45 studies), all of which were due to viral infections.

Fig. 1. PRISMA diagram.

Systematic review

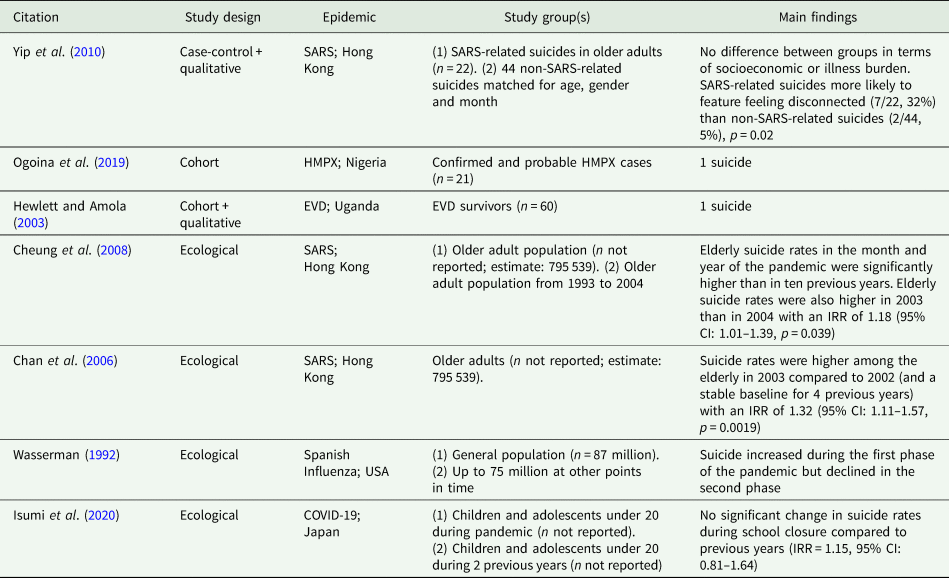

Death by suicide

In the seven studies describing death by suicide (Table 1), there were two cohort studies, one case-control study and four ecological studies, which reported at least 167 suicides.

Table 1. Studies reporting death by suicides

CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; EVD, Ebola virus disease; HMPX, human monkeypox; IRR, incidence rate ratio; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; USA, United States of America.

Four studies compared suicide incidence in epidemic and non-epidemic periods (Wasserman, Reference Wasserman1992; Chan et al., Reference Chan, Chiu, Lam, Leung and Conwell2006; Cheung et al., Reference Cheung, Chau and Yip2008; Isumi et al., Reference Isumi, Doi, Yamaoka, Takahashi and Fujiwara2020). One ecological study examining the impact of Spanish flu, World War I and the prohibition of alcohol on suicide in the general population found that all-cause mortality risks were positively correlated with death by suicide (Wasserman, Reference Wasserman1992). The author noted that suicide increased after the first wave of the pandemic in 1919, but that a similar effect was not evident after the second wave (Wasserman, Reference Wasserman1992). Two ecological studies examined the incidence of death by suicide among the elderly population in Hong Kong during the SARS epidemic. One study compared the year of the outbreak with the previous year, having shown stable suicide rates for four years prior to the outbreak, and found that suicides increased with an incidence rate ratio of 1.32 (95% CI: 1.11–1.57%) (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Chiu, Lam, Leung and Conwell2006). The peak was in April, at the worst point of the epidemic. Further analysis found the increased rate was restricted to older women and did not affect younger age groups. A second study confirmed this peak using a more complete data set (due to delays in suicide reporting) and also found a trough in suicides two months later, eliminating a usual seasonal peak and suggesting that some suicides may have been brought forward by the epidemic (Cheung et al., Reference Cheung, Chau and Yip2008). The study also found that the rate of suicide in the year following the epidemic remained above the pre-pandemic levels, despite having declined from the previous year. One cohort study in Japan of children and adolescents under the age of 20 found no significant change in suicide rates during the period of pandemic-related school closure compared to previous years (Isumi et al., Reference Isumi, Doi, Yamaoka, Takahashi and Fujiwara2020).

One study compared suicides believed to be related to SARS to suicides unrelated to SARS from the same year (Yip et al., Reference Yip, Cheung, Chau and Law2010). There were no differences between the groups in sociodemographic variables, history of psychiatric disorder, medical comorbidity or level of dependence on others, but feeling disconnected was more common in the individuals with SARS-related suicide. Among the suicides thought to be related to SARS, common problems were fear of infection, social isolation, disrupted routines and fear of being a burden to society.

Two small cohort studies each reported a single suicide in confirmed cases of Ebola virus disease (n = 60) and human monkeypox (n = 21) (Hewlett and Amola, Reference Hewlett and Amola2003; Ogoina et al., Reference Ogoina, Izibewule, Ogunleye, Ederiane, Anebonam, Neni, Oyeyemi, Etebu and Ihekweazu2019).

Self-harm

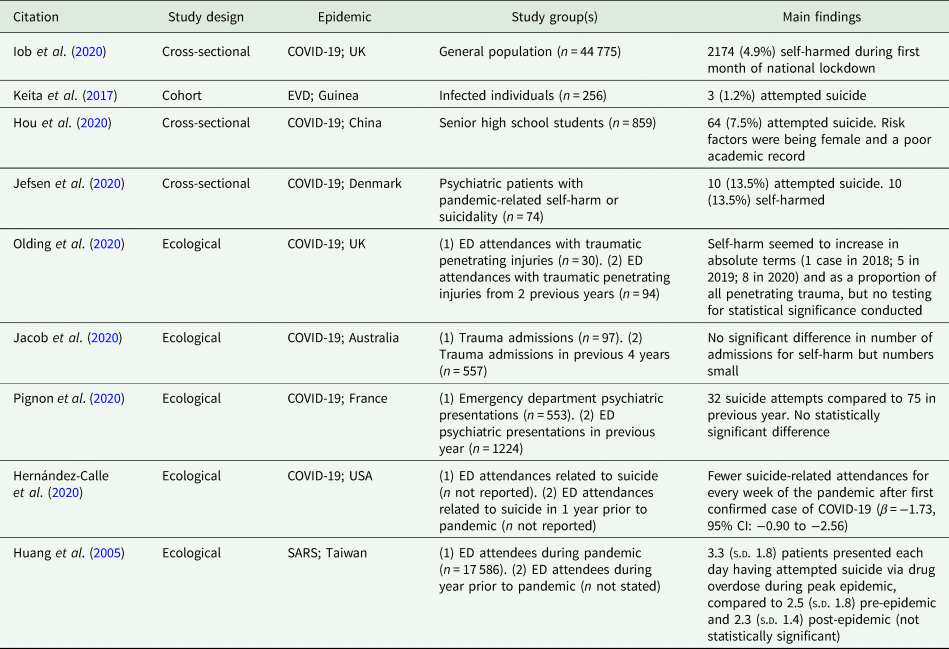

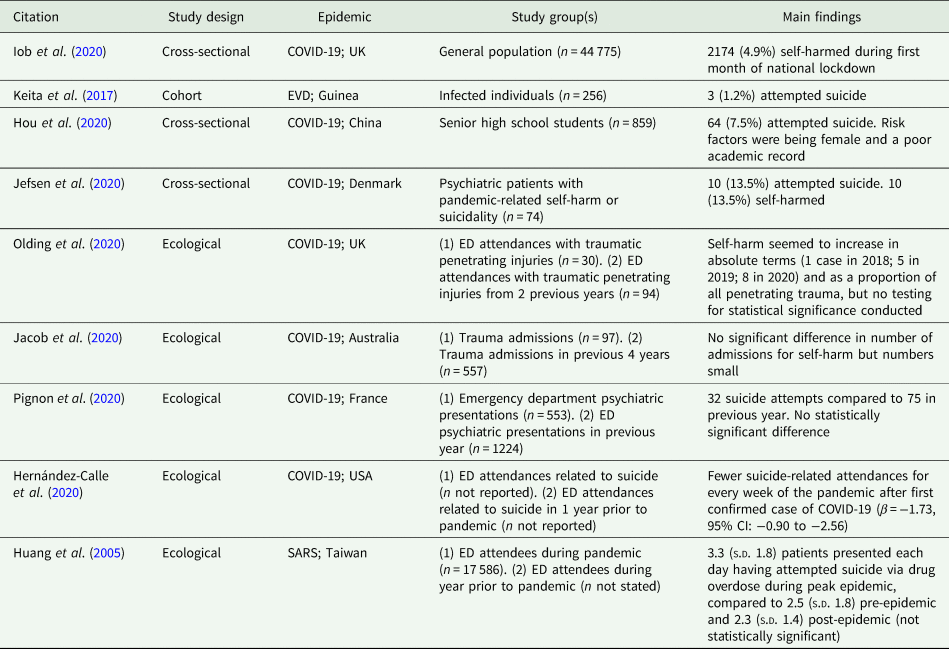

Of the nine studies describing self-harm summarised in Table 2, there were two cohort studies, two cross-sectional studies, and five ecological studies.

Table 2. Studies reporting self-harm

CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ED, emergency department; EVD, Ebola virus disease; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; s.d., standard deviation; USA, United States of America.

Five studies provided comparative data for epidemic and non-epidemic populations, all of which examined emergency department attendances for self-harm (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Yen, Huang, Kao, Wang, Huang and Lee2005; Hernández-Calle et al., Reference Hernández-Calle, Martínez-Alés, Mediavilla, Aguirre, Rodríguez-Vega and Bravo-Ortiz2020; Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Mwagiru, Thakur, Moghadam, Oh and Hsu2020; Olding et al., Reference Olding, Zisman, Olding and Fan2020; Pignon et al., Reference Pignon, Gourevitch, Tebeka, Dubertret, Cardot, Dauriac-Le Masson, Trebalag, Barruel, Yon, Hemery, Loric, Rabu, Pelissolo, Leboyer, Schürhoff and Pham-Scottez2020). One study during SARS examined attendances for suicide attempts via drug overdose, finding that on a background of reduced attendances overall and reduced attendances for psychiatric problems, in particular, attendances for overdose appeared to have increased, but this was not statistically significant (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Yen, Huang, Kao, Wang, Huang and Lee2005). Three studies of the COVID-19 pandemic showed no evidence of a difference in numbers of attendances (Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Mwagiru, Thakur, Moghadam, Oh and Hsu2020; Olding et al., Reference Olding, Zisman, Olding and Fan2020; Pignon et al., Reference Pignon, Gourevitch, Tebeka, Dubertret, Cardot, Dauriac-Le Masson, Trebalag, Barruel, Yon, Hemery, Loric, Rabu, Pelissolo, Leboyer, Schürhoff and Pham-Scottez2020) and one showed a reduction (Hernández-Calle et al., Reference Hernández-Calle, Martínez-Alés, Mediavilla, Aguirre, Rodríguez-Vega and Bravo-Ortiz2020), though numbers tended to be small.

Of the studies that did not present comparative data for epidemic and non-epidemic populations, four studies reported that between 1.2% (95% CI: 0.4–3.4%) and 13.5% (95% CI: 7.5–23.1%) of individuals self-harmed over a time period of between 30 days and 24 months (Keita et al., Reference Keita, Taverne, Sy Savané, March, Doukoure, Sow, Touré, Etard, Barry and Delaporte2017; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Mao, Dong, Cai and Deng2020; Iob et al., Reference Iob, Steptoe and Fancourt2020; Jefsen et al., Reference Jefsen, Rohde, Nørremark and Østergaard2020). In a cohort study of confirmed Ebola virus disease cases, three patients [1.2% (95% CI: 0.4–3.4%)] attempted suicide after discharge (Keita et al., Reference Keita, Taverne, Sy Savané, March, Doukoure, Sow, Touré, Etard, Barry and Delaporte2017). During COVID-19, one large representative survey found that 4.9% (95% CI: 4.6–5.1%) of the general population in the United Kingdom self-harmed in the first month of lockdown (Iob et al., Reference Iob, Steptoe and Fancourt2020). A much smaller sample of senior high school students in China during COVID-19 found that 7.5% (95% CI: 5.9–9.4%) had attempted suicide (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Mao, Dong, Cai and Deng2020). The highest prevalence was in an enriched sample of 74 psychiatric patients in Denmark with COVID-19-related self-harm or suicidality, of whom 10 (13.5%) attempted suicide and 10 (13.5%) self-harmed (Jefsen et al., Reference Jefsen, Rohde, Nørremark and Østergaard2020).

One study examined risk factors for suicide attempt among high school children, finding that being female and having a poor academic record were associated with increased risk (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Mao, Dong, Cai and Deng2020).

Thoughts of suicide or self-harm

In the 45 studies reporting data on thoughts of suicide or self-harm, as described in Table 3, there were six cohort studies, one case-control study, 30 cross-sectional studies, three ecological studies and five studies of internet search engine results.

Table 3. Studies reporting thoughts of suicide or self-harm

a Supplemented with additional information from the author.

aRR, adjusted risk ratio; BSI, Beck Suicide Ideation Scale; CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CRP, C-reactive protein; DSI-SS, Depression Symptom Index-Suicide Subscale; EVD, Ebola virus disease; ICU, intensive care unit; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; MTurk, Mechanical Turk; OCD, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; OR, odds ratio; SBQ-R, Suicide Behaviours Questionnaire-Revised; s.d., standard deviation; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America.

Five studies reported comparative results for epidemic and non-epidemic populations, all of which studied the COVID-19 pandemic. The most generalisable was a large web-based survey of US populations which reported that 10.7% of respondents reported having seriously considered suicide in the previous 30 days, which was compared to similar survey data from two years prior indicating a comparable figure of 4.3% (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019; Czeisler et al., Reference Czeisler, Lane, Petrosky, Wiley, Christensen, Njai, Weaver, Robbins, Facer-Childs, Barger, Czeisler, Howard and Rajaratnam2020). One study found that emergency department attendances with thoughts of suicide fell compared to the same period in the previous year (Smalley et al., Reference Smalley, Malone, Meldon, Borden, Simon, Muir and Fertel2020). Another study of individuals undergoing psychological assessments found no difference in the frequency of thoughts of suicide compared to individuals referred in the months prior to the epidemic (Titov et al., Reference Titov, Staples, Kayrouz, Cross, Karin, Ryan, Dear and Nielssen2020). One small cohort study that followed elderly people with depression before and during the epidemic found no evidence of a difference in frequency of thoughts of suicide (Hamm et al., Reference Hamm, Brown, Karp, Lenard, Cameron, Dawdani, Lavretsky, Miller, Mulsant, Pham, Reynolds, Roose and Lenze2020). A study of pregnant women found that thoughts of self-harm were more common during the pandemic than prior to it (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Zhang, Liu, Duan, Li, Fan, Li, Chen, Xu, Li, Guo, Wang, Li, Li, Zhang, You, Li, Yang, Tao, Xu, Lao, Wen, Zhou, Wang, Chen, Meng, Zhai, Ye, Zhong, Yang, Zhang, Zhang, Wu, Chen, Dennis and Huang2020b).

To consider the prevalence of thoughts of suicide and self-harm, we divided our studies by population into the general population, children or adolescents, health care workers, psychiatric patients, infected patients and recovered patients.

Studies of general populations found that reported frequency of thoughts of suicide or self-harm were present in between 0.9% (95% CI 0.0 to 5.0%) and 20.3% (95% CI 18.9 to 21.8%) over a time period of between 1 week and 2 weeks (Czeisler et al., Reference Czeisler, Lane, Petrosky, Wiley, Christensen, Njai, Weaver, Robbins, Facer-Childs, Barger, Czeisler, Howard and Rajaratnam2020; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Tan, Jiang, Zhang, Zhao, Zou, Hu, Luo, Jiang, McIntyre, Tran, Sun, Zhang, Ho, Ho and Tam2020; Iob et al., Reference Iob, Steptoe and Fancourt2020; Kaparounaki et al., Reference Kaparounaki, Patsali, Mousa, Papadopoulou, Papadopoulou and Fountoulakis2020; Killgore et al., Reference Killgore, Cloonan, Taylor, Allbright and Dailey2020a; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Park, Shin, Lee, Chung, Lee, Kim, Jung, Lee, Yum, Lee, Koh, Ko, Lim, Lee, Lee, Choi, Han, Shin, Lee, Kim and Kim2020; Li et al., Reference Li, Ko, Chen, Wang, Chang, Yen and Lu2020; Tan et al., Reference Tan, Hao, McIntyre, Jiang, Jiang, Zhang, Zhao, Zou, Hu, Luo, Zhang, Lai, Ho, Tran, Ho and Tam2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Hegde, Son, Keller, Smith and Sasangohar2020; Xin et al., Reference Xin, Luo, She, Yu, Li, Wang, Ma, Tao, Zhang, Zhao, Li, Hu, Zhang, Gu, Lin, Wang, Cai, Wang, You, Hu and Lau2020). In children and adolescents, one study found thoughts of suicide to be present in 31.3% (95% CI: 28.3–34.5%) over a time period of 6 months (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Mao, Dong, Cai and Deng2020). Among health care workers, thoughts of suicide or self-harm were found to be present in between 2.4% (95% CI: 0.3–8.2%) and 13.9%. (95% CI: 12.3–15.6%) over a time period of between 14 days and 30 days (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Feng, Huang, Wang, Wang, Lu, Xie, Wang, Liu, Hou, Ouyang, Pan, Li, Fu, Deng and Liu2020; Sharif et al., Reference Sharif, Amin, Hafiz, Benzel, Peev, Dahlan, Enchev, Pereira and Vaishya2020; Shen et al., Reference Shen, Zou, Zhong, Yan and Li2020; Xiaoming et al., Reference Xiaoming, Ming, Su, Wo, Jianmei, Qi, Hua, Xuemei, Lixia, Jun, Lei, Zhen, Lian, Jing, Handan, Haitang, Xiaoting, Xiaorong, Ran, Qinghua, Xinyu, Jian, Jing, Guanghua, Zhiqin, Nkundimana and Li2020). Among patients with pre-existing mental illnesses, thoughts of suicide or self-harm occurred in between 9.1% (95% CI: 2.5–21.7%) and 27.5% (95% CI: 25.1–30.0%) over a time period of 14 days (Benatti et al., Reference Benatti, Albert, Maina, Fiorillo, Celebre, Girone, Fineberg, Bramante, Rigardetto and Dell'Osso2020; Hamm et al., Reference Hamm, Brown, Karp, Lenard, Cameron, Dawdani, Lavretsky, Miller, Mulsant, Pham, Reynolds, Roose and Lenze2020; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Tan, Jiang, Zhang, Zhao, Zou, Hu, Luo, Jiang, McIntyre, Tran, Sun, Zhang, Ho, Ho and Tam2020; Titov et al., Reference Titov, Staples, Kayrouz, Cross, Karin, Ryan, Dear and Nielssen2020). Among infected individuals who were acutely unwell, thoughts of suicide or self-harm were present in between 2.0% (95% CI: 0.5–6.9%) (measured in retrospect) and 24.5% (95% CI: 16.7–33.8%) (measured contemporaneously) over a time period of 14 days (Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Cheng, Lau, Li and Chan2005; Qian et al., Reference Qian, Caihong, Renjie and Yuan2020). Five studies examined individuals who had recovered from the epidemic infection, finding the frequency of thoughts of suicide or self-harm of between 0.0% (95% CI: 0.0–3.6%) and 15.7% (95% CI: 13.9–17.7%) over a time period of between ‘several days’ and a mean of 42 days (Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Cheng, Lau, Li and Chan2005; Bowen et al., Reference Bowen, Smith, Steinbach, Billioux, Summers, Azodi, Ohayon, Schindler and Nath2016; Keita et al., Reference Keita, Taverne, Sy Savané, March, Doukoure, Sow, Touré, Etard, Barry and Delaporte2017; Secor et al., Reference Secor, Macauley, Stan, Kagone, Sidikiba, Sow, Aronovich, Litvin, Davis, Alva and Sanderson2020; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Hu, Song, Yang, Xu, Cheng, Chen, Zhong, Jiang, Xiong, Lang, Tao, Lin, Shi, Lu, Pan, Xu, Zhou, Song, Wei, Zheng and Du2020a).

Risk factors identified for thoughts of suicide or self-harm in the general population were young age (Czeisler et al., Reference Czeisler, Lane, Petrosky, Wiley, Christensen, Njai, Weaver, Robbins, Facer-Childs, Barger, Czeisler, Howard and Rajaratnam2020; Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick, Harris and Drawve2020; Li et al., Reference Li, Ko, Chen, Wang, Chang, Yen and Lu2020), ethnic minority background (Czeisler et al., Reference Czeisler, Lane, Petrosky, Wiley, Christensen, Njai, Weaver, Robbins, Facer-Childs, Barger, Czeisler, Howard and Rajaratnam2020; Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick, Harris and Drawve2020), essential worker status (Czeisler et al., Reference Czeisler, Lane, Petrosky, Wiley, Christensen, Njai, Weaver, Robbins, Facer-Childs, Barger, Czeisler, Howard and Rajaratnam2020), families with children (Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick, Harris and Drawve2020), being unmarried (Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick, Harris and Drawve2020), prior psychiatric disorder (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Tan, Jiang, Zhang, Zhao, Zou, Hu, Luo, Jiang, McIntyre, Tran, Sun, Zhang, Ho, Ho and Tam2020), poorer physical health (Li et al., Reference Li, Ko, Chen, Wang, Chang, Yen and Lu2020), current lockdown (Gratz et al., Reference Gratz, Tull, Richmond, Edmonds, Scamaldo and Rose2020; Killgore et al., Reference Killgore, Cloonan, Taylor, Allbright and Dailey2020a), less social support (Li et al., Reference Li, Ko, Chen, Wang, Chang, Yen and Lu2020), lower psychological resilience (Killgore et al., Reference Killgore, Taylor, Cloonan and Dailey2020e), concern about COVID-19 (Ahorsu et al., Reference Ahorsu, Imani, Lin, Timpka, Broström, Updegraff, Årestedt, Griffiths and Pakpour2020; Islam et al., Reference Islam, Bodrud-Doza, Khan, Haque and Mamun2020; Killgore et al., Reference Killgore, Cloonan, Taylor, Fernandez, Grandner and Dailey2020c; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Zhang, Liu, Duan, Li, Fan, Li, Chen, Xu, Li, Guo, Wang, Li, Li, Zhang, You, Li, Yang, Tao, Xu, Lao, Wen, Zhou, Wang, Chen, Meng, Zhai, Ye, Zhong, Yang, Zhang, Zhang, Wu, Chen, Dennis and Huang2020b), lower adherence to infection control guidance (Li et al., Reference Li, Ko, Chen, Wang, Chang, Yen and Lu2020), loneliness and (Killgore et al., Reference Killgore, Cloonan, Taylor and Dailey2020b, Reference Killgore, Cloonan, Taylor, Miller and Dailey2020d) insomnia (Killgore et al., Reference Killgore, Cloonan, Taylor, Fernandez, Grandner and Dailey2020c). There was no evidence for the difference in the prevalence of thoughts of suicide when comparing hospital staff to the general population (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Wang, Sun, Qian, Liu, Wang, Qi, Yang, Song, Zhou, Zeng, Liu, Li and Zhang2020), or when comparing frontline v. non-frontline health care staff (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Feng, Huang, Wang, Wang, Lu, Xie, Wang, Liu, Hou, Ouyang, Pan, Li, Fu, Deng and Liu2020). Among children, risk factors were being female, poor academic attainment and having no siblings (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Mao, Dong, Cai and Deng2020).

Three studies considered the relationship between economic factors and outcomes. One found a weak positive correlation between a recent job loss and suicide risk (r = 0.12, p < 0.01) (Gratz et al., Reference Gratz, Tull, Richmond, Edmonds, Scamaldo and Rose2020). The other two presented period prevalences by income brackets. A large UK study found a higher prevalence in lower-income groups (28.2% in the lowest stratum compared to 12.1% in the highest) (Iob et al., Reference Iob, Steptoe and Fancourt2020), whereas there was little difference in a large US survey with a tendency towards the opposite trend (9.9% in the lowest stratum compared to 11.6% in the highest) (Czeisler et al., Reference Czeisler, Lane, Petrosky, Wiley, Christensen, Njai, Weaver, Robbins, Facer-Childs, Barger, Czeisler, Howard and Rajaratnam2020).

5.3.1.1 Search engine results

Five studies assessed trends of searches for terms related to suicide as a proxy measure for thoughts of suicide using the search engine Google (Halford et al., Reference Halford, Lake and Gould2020; Jacobson et al., Reference Jacobson, Lekkas, Price, Heinz M, Song, O'Malley and Barr2020; Knipe et al., Reference Knipe, Evans, Marchant, Gunnell and John2020; Rana, Reference Rana2020; Sinyor et al., Reference Sinyor, Spittal and Niederkrotenthaler2020). One study in the United Kingdom, United States and Italy examining data from January to March 2020 found that suicide-related searches fell as the number of COVID-19 deaths started to rise but increased again after the lockdown was announced in each country (Knipe et al., Reference Knipe, Evans, Marchant, Gunnell and John2020). However, another study looking at data in the United States made comparisons between states and examined the relationship between frequency of suicide-related searches and enactment of official stay-at-home orders, finding that an increase in suicide-related searches prior to the enactment of orders levelled off once these were implemented (Jacobson et al., Reference Jacobson, Lekkas, Price, Heinz M, Song, O'Malley and Barr2020). One study of data from India found that there was a positive but weak correlation between the daily number of COVID-19 death reports and suicide-related searches over 52 days (Rana, Reference Rana2020). Two studies compared search frequency with a period prior to the pandemic, both of which found overall reductions in suicide-related search terms, although Halford et al., found that use of terms related to some known suicide risk factors, such as unemployment, was increased (Halford et al., Reference Halford, Lake and Gould2020; Sinyor et al., Reference Sinyor, Spittal and Niederkrotenthaler2020).

Quality assessment

Overall, across the 57 studies, the mean score on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was 3.0 (s.d. 2.0). In total, 42 studies (74%) were deemed of low quality, 9 (16%) of moderate quality and only 6 (11%) of high quality. In terms of the domains of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, the mean score was 1.9 out of a maximum score of 4 (47%) on the selection domain, 0.8 out of 2 (42%) on the comparability domain, and 0.7 out of 3 (24%) on the outcome domain. The Main weaknesses were a lack of demonstration of an outcome at baseline, inadequate follow-up duration and high rates of loss at follow-up. The quality assessment rating for each paper is provided in the online Supplementary Material (pp. 6–9).

Meta-analysis

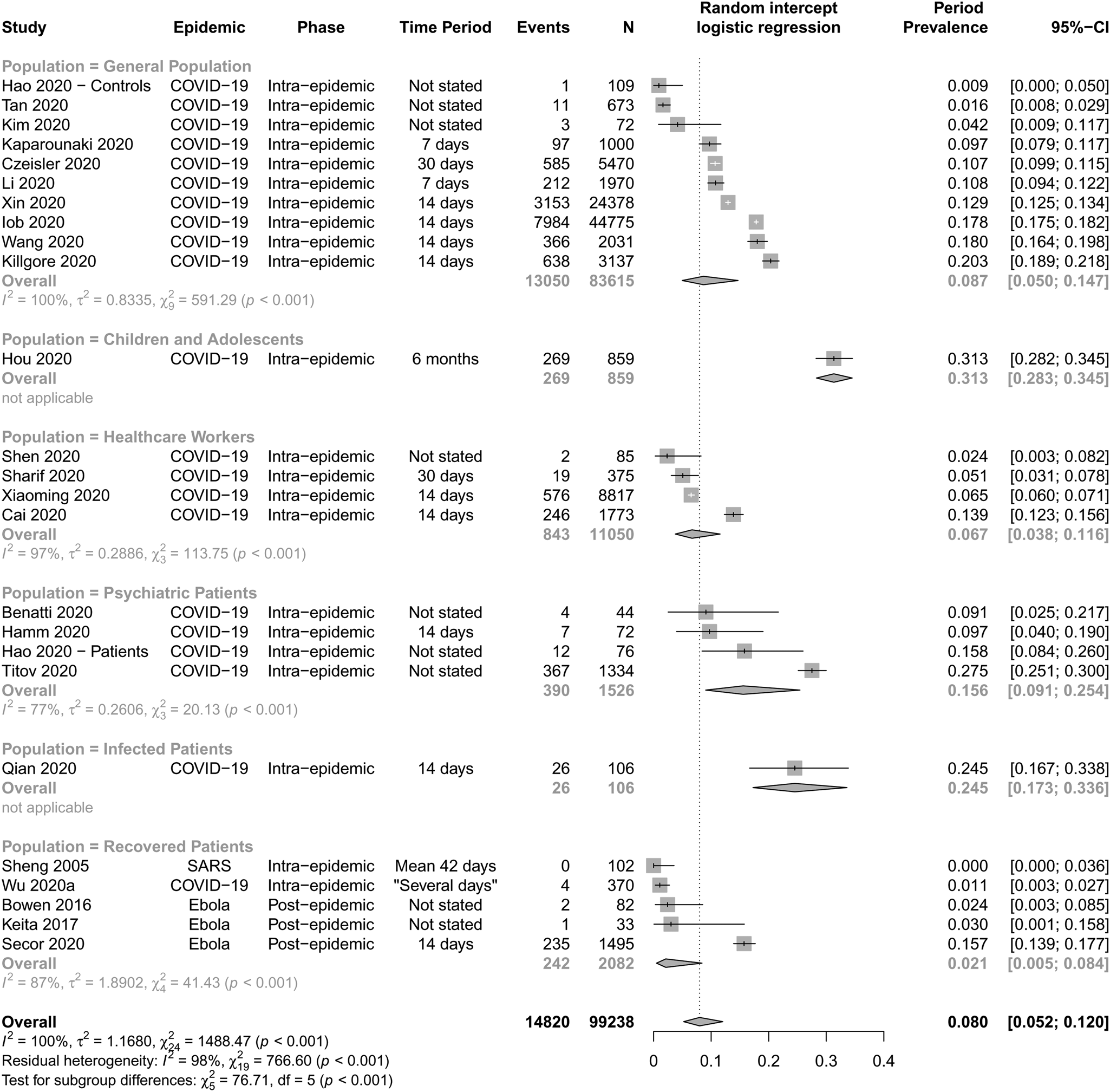

Meta-analysis was not possible for suicide or self-harm because results were not reported consistently between studies and actual numbers of events were frequently not available. For thoughts of suicide and self-harm, 24 studies contributed data on period prevalences with a total of 25 separate samples (see Fig. 2). These were separated into six distinct population subgroups (general population, children and adolescents, health care workers, psychiatric patients, infected patients and recovered patients). Overall, the period prevalence of thoughts of suicide and self-harm was 8.0% (95% CI: 5.2–12.0%; 14 820 of 99 238 cases in 24 studies) over a time period of between 7 days and 6 months. Among subgroups, prevalence was 8.7% (95% CI: 5.0–14.7%; 13 050 of 83 615 cases in ten studies) in the general population, 31.3% (95% CI: 28.3–34.5%; 269 of 859 cases in one study) in children and adolescents, 6.7% (95% CI: 3.8–11.6%; 843 of 11 050 cases in four studies) in health care workers, 15.6% (95% CI: 9.1–25.4%; 390 of 1526 cases in four studies) in psychiatric patients, 24.5% (95% CI: 17.3–33.6%; 26 of 106 cases in one study) in infected patients, and 2.1% (95% CI: 0.5–8.4%; 242 of 2082 cases in five studies) in recovered patients (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Forest plot for the period prevalence of thoughts of suicide or self-harm.

There were significant differences between certain population subgroups. Prevalence was significantly higher in children and adolescents compared to recovered patients (p < 0.001), psychiatric patients (p = 0.005), health care workers (p < 0.001) and the general population (p < 0.001). Prevalence was significantly higher in infected patients than in health care workers (p < 0.001), the general population (p = 0.003), and recovered patients (p < 0.001). Prevalence was significantly lower in recovered patients than in psychiatric patients (p = 0.023). There were no significant differences in prevalence between other subgroups (p > 0.05). There was one very high estimate, which was distinct in being the only study examining children and adolescents and in studying the longest time period (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Mao, Dong, Cai and Deng2020). In a subgroup analysis by phase in the epidemic (Online Supplementary Fig. 7), only three studies were post-epidemic, while the rest were during an epidemic; there was no significant difference between these subgroups (p = 0.58) (online Supplementary material p. 23).

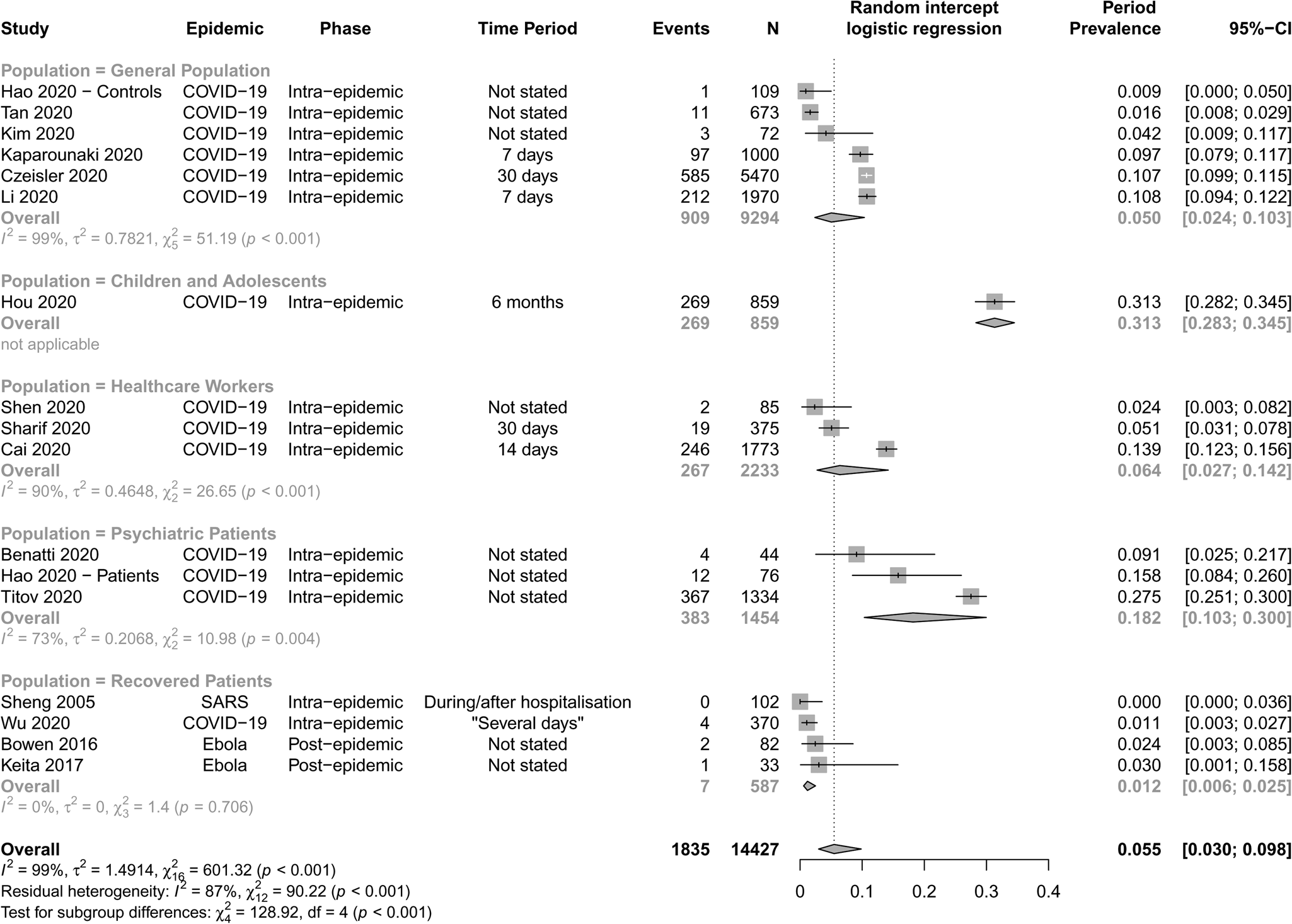

Between-study heterogeneity was high (I 2 = 100%, p < 0.001) and remained high when stratified by population subgroup (I 2 = 98%, p < 0.001). Meta-regression of type of assessment showed a significantly higher period prevalence of thoughts of suicide or thoughts of self-harm (14.9%, 95% CI: 11.3–19.4%; 12 985 of 84 811 cases in eight studies) compared to thoughts of suicide alone (5.5%, 95% CI: 3.0–9.8%; 1835 of 14 427 cases in 16 studies). Studies describing only thoughts of suicide are shown in Fig. 3. Sensitivity analysis did not suggest that the meta-analytic estimate changed when removing any one study (online Supplementary Material pp. 17–21), but a sensitivity analysis did show a higher prevalence in the two moderate quality studies, compared to the others (all of which were of low quality) [10.7% (95% CI: 9.9–11.5%) v. 7.5% (95% CI 4.7–11.7%); p = 0.04] (online Supplementary material p. 22).

Fig. 3. Forest plot for the period prevalence of thoughts of suicide.

Discussion

This study aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature on suicide, self-harm and thoughts of suicide or self-harm during infectious epidemics. We found little high-quality evidence comparing these outcomes to non-epidemic periods and the scope for generalisation is very limited. This work highlights the need for real-time monitoring of suicide, self-harm and thoughts of suicide or self-harm both during epidemics and in non-epidemic periods that can act as comparison groups.

In terms of death by suicide, studies of only two populations provide clear comparative evidence for the relationship between suicide and infectious epidemics, although both use an ecological design. The first describes an increase in suicides among the elderly in Hong Kong during SARS (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Chiu, Lam, Leung and Conwell2006; Cheung et al., Reference Cheung, Chau and Yip2008), but this was restricted to women and did not extend to other age groups. The second examined suicide in Japan in those under the age of 20 and found no difference in frequency compared to previous years (Isumi et al., Reference Isumi, Doi, Yamaoka, Takahashi and Fujiwara2020).

In terms of self-harm, attendances to emergency departments showed no evidence of change compared to previous years in four studies (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Yen, Huang, Kao, Wang, Huang and Lee2005; Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Mwagiru, Thakur, Moghadam, Oh and Hsu2020; Olding et al., Reference Olding, Zisman, Olding and Fan2020; Pignon et al., Reference Pignon, Gourevitch, Tebeka, Dubertret, Cardot, Dauriac-Le Masson, Trebalag, Barruel, Yon, Hemery, Loric, Rabu, Pelissolo, Leboyer, Schürhoff and Pham-Scottez2020), and a decrease in one study (Hernández-Calle et al., Reference Hernández-Calle, Martínez-Alés, Mediavilla, Aguirre, Rodríguez-Vega and Bravo-Ortiz2020), although numbers were generally small. Again, several studies found that a significant minority of individuals during an epidemic self-harmed, but the lack of comparison groups limits conclusions.

There is a greater quantity of evidence regarding thoughts of suicide and self-harm, although little of it provides a comparison to non-epidemic populations. One large US survey found that suicidal ideation was substantially more common than in previous years (Czeisler et al., Reference Czeisler, Lane, Petrosky, Wiley, Christensen, Njai, Weaver, Robbins, Facer-Childs, Barger, Czeisler, Howard and Rajaratnam2020), as did a study of pregnant women (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Zhang, Liu, Duan, Li, Fan, Li, Chen, Xu, Li, Guo, Wang, Li, Li, Zhang, You, Li, Yang, Tao, Xu, Lao, Wen, Zhou, Wang, Chen, Meng, Zhai, Ye, Zhong, Yang, Zhang, Zhang, Wu, Chen, Dennis and Huang2020b), but three studies of specific populations found no difference (Hamm et al., Reference Hamm, Brown, Karp, Lenard, Cameron, Dawdani, Lavretsky, Miller, Mulsant, Pham, Reynolds, Roose and Lenze2020; Smalley et al., Reference Smalley, Malone, Meldon, Borden, Simon, Muir and Fertel2020; Titov et al., Reference Titov, Staples, Kayrouz, Cross, Karin, Ryan, Dear and Nielssen2020). Meta-analysis showed that overall the prevalence of thoughts of suicide or self-harm was 8.0% (95% CI: 5.2–12.0%) and prevalence of thoughts of suicide was 5.5% (95% CI: 3.0–9.8%) in those affected by an infectious epidemic, which is somewhat higher than the 12-month prevalence estimate of 2.0% (95% CI: 1.9–2.2%) from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys conducted in 21 countries (Borges et al., Reference Borges, Nock, Haro Abad, Hwang, Sampson, Alonso, Andrade, Angermeyer, Beautrais, Bromet, Bruffaerts, de Girolamo, Florescu, Gureje, Hu, Karam, Kovess-Masfety, Lee, Levinson, Medina-Mora, Ormel, Posada-Villa, Sagar, Tomov, Uda, Williams and Kessler2010). However, when the results were broken up into subgroups, differences emerged. Notably, one study of high-school students found higher rates of thoughts of suicide or self-harm than in the general population (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Mao, Dong, Cai and Deng2020), although this is commonly the case outside of epidemics (Borges et al., Reference Borges, Nock, Haro Abad, Hwang, Sampson, Alonso, Andrade, Angermeyer, Beautrais, Bromet, Bruffaerts, de Girolamo, Florescu, Gureje, Hu, Karam, Kovess-Masfety, Lee, Levinson, Medina-Mora, Ormel, Posada-Villa, Sagar, Tomov, Uda, Williams and Kessler2010; McKinnon et al., Reference McKinnon, Gariépy, Sentenac and Elgar2016). There was also evidence from a single study that thought of suicide or self-harm may be common in infected patients (Qian et al., Reference Qian, Caihong, Renjie and Yuan2020). These results must be interpreted with caution, however, due to the diversity in measures used and the lack of head-to-head comparisons. In other subgroups that might be hypothesised to be at high risk (health care workers, recovered patients and psychiatric patients) we found no greater prevalence than in the general population. Moreover, it is established that only a minority of those with thoughts of suicide will attempt or die by suicide (Turecki and Brent, Reference Turecki and Brent2016).

Monitoring internet search engine terms related to suicide is an even more indirect measure of suicides and risks conflating increased interest in suicide secondary to media concerns with thoughts of suicide per se. It does, however, offer the promise of real-time monitoring of a population and studies have noted a longitudinal or geographical association between suicide-related search terms and death by suicide (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Tsai, Huang and Peng2011; Hagihara et al., Reference Hagihara, Miyazaki and Abe2012; Gunn and Lester, Reference Gunn and Lester2013; Barros et al., Reference Barros, Melia, Francis, Bogue, O'Sullivan, Young, Bernert, Rebholz-Schuhmann and Duggan2019). Although this has not been a universal finding (Sueki, Reference Sueki2011) to date, the data concerning COVID-19 suggest that at the level of day-by-day variation, there is a positive association between suicide-related search terms and the COVID-19 death rate (Jacobson et al., Reference Jacobson, Lekkas, Price, Heinz M, Song, O'Malley and Barr2020; Knipe et al., Reference Knipe, Evans, Marchant, Gunnell and John2020; Rana, Reference Rana2020), but not when a larger time frame is examined (Halford et al., Reference Halford, Lake and Gould2020; Sinyor et al., Reference Sinyor, Spittal and Niederkrotenthaler2020).

Our study has several limitations, both in terms of the underlying evidence of the original articles and in the data synthesis. In terms of the original articles, in spite of the wealth of publicly available data on suicides globally, it was striking how little high-quality evidence was present in the peer-reviewed literature. The quality of studies was generally poor, with only 6 (11%) constituting high-quality evidence. The most common deficits were in the study outcomes, where follow-up was frequently inadequate and there were few studies that examined the years following an epidemic. Most studies focused on thoughts of suicide and self-harm, rather than death by suicide and self-harm and many studies relied on small samples. In addition, much of the data has been collected and reported whilst partway through a pandemic, giving an incomplete picture and not allowing longer-term follow-up. Some studies, particularly those relying on online surveys, are susceptible to selection bias because of variability in internet access and a tendency for completion rates to be related to demographic, financial and health-related outcomes of interest (Couper et al., Reference Couper, Kapteyn, Schonlau and Winter2007). Measurement bias is also likely since epidemics might change reporting practices for suicide, potentially resulting in under-reporting. The low quality of the majority of studies and the lack of control groups mean that our conclusions must be cautious. Our sensitivity analysis by study quality demonstrated that poor-quality studies may underestimate the prevalence of thoughts of suicide or self-harm. There are also issues with the generalisability of the results, given the high proportion of studies originating from China and the United States as well as a focus on quite specific subgroups. Interpretation of ecological studies risks conflating the exposure of a population with the exposure of individuals.

In terms of the process of conducting this systematic review, there were also inherent limitations, not least the extremely rapid growth of the literature, which more than doubled between the first and second database search. It is, therefore, impossible to be completely up-to-date, though we can discuss the different forms of data available, their contributions and their limitations. Our original protocol had to be adapted because it became apparent that some of our planned subgroup analyses would not be feasible because of lack of reporting of certain population characteristics and two of the eventual six subgroups only contained a single study each. Because original data were generally not available, our meta-analysis relied on aggregate – rather than an individual participant – data, which resulted in a loss of potentially interesting trends within studies. Very high heterogeneity between studies, which remained even after stratification by population subgroup, weakens the strength of any conclusions. Reasons for this heterogeneity likely include the populations studied, the period in question and the specific outcome measure. In particular, our results showed that the outcome used markedly affected prevalence figures for thoughts of suicide or self-harm, as studies that reported thoughts of suicide alone showed much lower estimates than those which also included thoughts of self-harm. The different time periods investigated in the various studies means that the pooled figures should be regarded with caution.

Our first conclusion must be that there is a substantial lack of evidence on the important and urgent question of whether the frequency of suicide, self-harm and thoughts of suicide or self-harm change during infectious epidemics. This is consistent with the findings of previous, less exhaustive reviews (Leaune et al., Reference Leaune, Samuel, Oh, Poulet and Brunelin2020; Zortea et al., Reference Zortea, Brenna, Joyce, McClelland, Tippett, Tran, Arensman, Corcoran, Hatcher, Heise, Links, O'Connor, Edgar, Cha, Guaiana, Williamson, Sinyor and Platt2020). The evidence that exists is generally of low quality and is inadequate to answer the relevant questions. There have been only two epidemics in two populations where robust data have been published in the peer-review literature examining the impact on death by suicide, finding that suicide was more frequent among the elderly during SARS and that there was no evidence of a difference in suicide frequency among children and adolescents during COVID-19 in Japan. However, more evidence is now starting to accumulate. Recent data from outside the search window of this systematic review in Norway and Australia have found no change in suicide rates during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to previous years (Knudsen et al., Reference Knudsen, Stene-Larsen, Gustavson, Hotopf, Kessler, Krokstad, Skogen, Øverland and Reneflot2021; Leske et al., Reference Leske, Kõlves, Crompton, Arensman and de Leo2021). A Swedish study has recently found no correlation between influenza deaths over almost nine decades – including Spanish Flu – and a modest drop in suicides during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the previous year (Rück et al., Reference Rück, Mataix-Cols, Malki, Adler, Flygare, Runeson and Sidorchuk2020).

Most of the available evidence suggests that the frequency of actual self-harm presentations to emergency departments does not change during a pandemic, but this is likely a small and unrepresentative sample of total self-harm. It is unclear whether thoughts of suicides change in prevalence during infectious epidemics. The largest study reviewed suggested a substantial increase in the United States (Czeisler et al., Reference Czeisler, Lane, Petrosky, Wiley, Christensen, Njai, Weaver, Robbins, Facer-Childs, Barger, Czeisler, Howard and Rajaratnam2020), which is echoed by more recent data from the Czech Republic (Winkler et al., Reference Winkler, Formanek, Mlada, Kagstrom, Mohrova, Mohr and Csemy2020). However, the findings from smaller studies were variable. Results from studies of internet search trends actually suggest a reduction in thoughts of suicides compared to non-epidemic periods. There was some evidence that certain groups, such as the young and ethnic minorities, may be at higher risk of thoughts of suicide. It is unclear to what extent evidence collected during previous epidemics may be relevant to the COVID-19 pandemic, as the global reach of COVID-19 and the relatively low case-fatality rate distinguishes it markedly from SARS and Ebola virus disease (Chan-Yeung and Xu, Reference Chan-Yeung and Xu2003; Kucharski and Edmunds, Reference Kucharski and Edmunds2014; Rajgor et al., Reference Rajgor, Lee, Archuleta, Bagdasarian and Quek2020).

The most urgent application of this study is for the development of up-to-date suicide estimates or even near real-time surveillance systems, which can inform policy making in the same way that a daily COVID-19 death toll does. There would be caveats to such data, as corrections may emerge at a later date, given difficulties in determining the cause of death in some cases. However, it is possible to undertake and UK data have already been presented, although not yet in peer-reviewed journals. These have shown that in several parts of England, there was no evidence of change in monthly suicides after the initiation of a lockdown (Appleby et al., Reference Appleby, Kapur, Turnbull and Richards2020) and that nationally child suicides may have become more frequent, but this did not reach statistical significance (Odd et al., Reference Odd, Sleap, Appleby, Gunnell and Luyt2020). Second, existing national and international suicide data should be analysed to ascertain the relationship with past epidemics. Third, in the aftermath of the current pandemic, studies of the impact of suicide will be required with robust geographical, temporal and policy-related comparisons, investigating the impact of interventions such as lockdown on suicide. These will need to have a prolonged follow-up period, as the effects of the economic crisis on suicide have been shown to be delayed by up to several years (Iglesias-García et al., Reference Iglesias-García, Sáiz, Burón, Sánchez-Lasheras, Jiménez-Treviño, Fernández-Artamendi, Al-Halabí, Corcoran, García-Portilla and Bobes2017). Fourth, studying thoughts of suicide may benefit from the timely use of electronic health apps. Fifth, reproducible and representative studies should be regularly conducted during non-epidemic periods to provide a point of comparison for subsequent studies. Lastly, in the context of suicide research, we note limitations on the use of certain measures – such as the PHQ-9 – that do not distinguish thoughts of suicide from thoughts of self-harm, as the information they provide may be too non-specific to be useful.

Beyond the need for further policy-driven research, there must be consideration of the potential changes in the numbers of suicides (mediated by unemployment, loneliness and reduced access to mental health services) in the models of the effects of efforts to control the pandemic. The media and policy-makers must avoid contributing to public alarm about suicide without sufficient evidence, given that data are so scarce on the subject; guidance for responsible reporting of suicides should be followed, including ensuring that suicides are not presented simplistically as caused solely by the current pandemic (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Marzano, Fraser, Hawley, Harris-Skillman and Lainez2020; Independent Press Standards Organisation, 2020; Reger et al., Reference Reger, Stanley and Joiner2020). As has previously been suggested, there are steps that policy-makers can take to reduce suicide that could have positive results far beyond the present pandemic (Moutier, Reference Moutier2020).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796021000214.

Data

Data extraction tables and R code will be made available to any interested parties on request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Mark É. Czeisler and Dr William D. S. Killgore for their advice in preparing this manuscript.

Author contributions

JPR, EC and ASD originally designed the study. NB conducted the de-duplication in consultation with JPR. JPR and EC screened the studies. EC, NB, AS and JPR extracted the data in consultation with GL and ASD. DO conducted the meta-analysis with advice from PFP. JPR, AS, EC and DO conducted the quality assessment. SW assisted with data extraction and quality assessment in Chinese. JPR wrote the first draft of the manuscript with input from EC and DO. All authors contributed to the final design of the study and the final manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (JPR, grant number: 102186/B/13/Z), the UK National Institute for Health Research (EC, grant number: NIHR300273), the UK Medical Research Council (DO, grant number: MR/N013700/1) and the NIHR University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre (GL; ASD).

Conflict of interest

PF-P reports personal fees from Lundbeck, outside the submitted work. All other authors declare no competing interests.