Introduction

Family planning has been shown to improve women's and children's lives in a multitude of ways (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Li, Liu and Tsui2012; Cleland et al., Reference Cleland, Conde-Agudelo, Peterson, Ross and Tsui2012). Although much research to date has focused on socio-economic determinants of the uptake of family planning (Tadele et al., Reference Tadele, Abebaw and Ali2019), few investigators have studied the impact of poor mental health on women's reproductive behaviours in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). There is evidence from high-income countries that depression is associated with increased rates of unintended pregnancy in young adulthood and shorter pregnancy spacing (Patchen et al., Reference Patchen, Caruso and Lanzi2009; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Kusunoki, Gatny and Barber2014; Corcoran, Reference Corcoran2016). Depression and stress have also been found to be associated with lower rates of contraceptive use and choice of less effective methods, mostly in clinical samples from North America (Garbers et al., Reference Garbers, Correa, Tobier, Blust and Chiasson2010; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Moreau, Trussell and Barber2013a, Reference Hall, Moreau, Trussell and Barberb). Despite the high prevalence of common mental disorders (CMDs) in women of reproductive age in LMICs (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Cabral de Mello, Patel, Rahman, Tran, Holton and Holmes2012) and mounting evidence of the impact of CMDs on infant illness rates (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Iqbal, Bunn, Lovel and Harrington2004; Ross et al., Reference Ross, Hanlon, Medhin, Alem, Tesfaye, Worku, Dewey, Patel and Prince2011), and reduced help-seeking of the mother on behalf of her child (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Iqbal, Bunn, Lovel and Harrington2004), less focus has been given to how maternal CMDs may impact a woman's behaviours pertaining to her own health.

Ethiopia embraced the Family Planning 2020 commitment (Family Planning, 2020), aiming to increase contraceptive use prevalence to 55% and reach an additional 6.2 million women by 2020 (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Druce, Bunting, Radloff, Koroma and Gupta2014). Although evidence shows that the rates of family planning uptake were increasing rapidly in Ethiopia pre-FP2020 pledge, the growth rate seems to have stalled in recent years (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Choi, Rimon, Alzouma, Gichangi, Guiella, Kayembe, Kibira, Makumbi, OlaOlorun, Omoluabi, Otupiri, Oumarou, Seme, Shiferaw, Anglewicz, Radloff and Tsui2019). In the Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey (DHS) 2016, 22% of married women reported unmet need for family planning (CSA Addis Ababa and ICF, 2016); the number was higher in rural than in urban areas and there were wide regional and socio-demographic variations. The follow-up mini DHS 2019 showed a contraceptive prevalence rate of 41%, an improvement from 35% in 2016 but still below the FP2020 pledge (EPHI and ICF, 2019). Previous population studies in Ethiopia have shown that CMD symptoms are common in the perinatal period and are associated with impaired maternal functioning (Senturk et al., Reference Senturk, Hanlon, Medhin, Dewey, Araya, Alem, Prince and Stewart2012), however to our knowledge, no previous studies have explored if CMD symptoms impact women's uptake of family planning.

We therefore aimed to investigate (1) if CMD symptoms were prospectively associated with unmet need for contraception and (2) if high CMD symptoms impacted fertility rate in a cohort of women in rural Ethiopia.

Methods

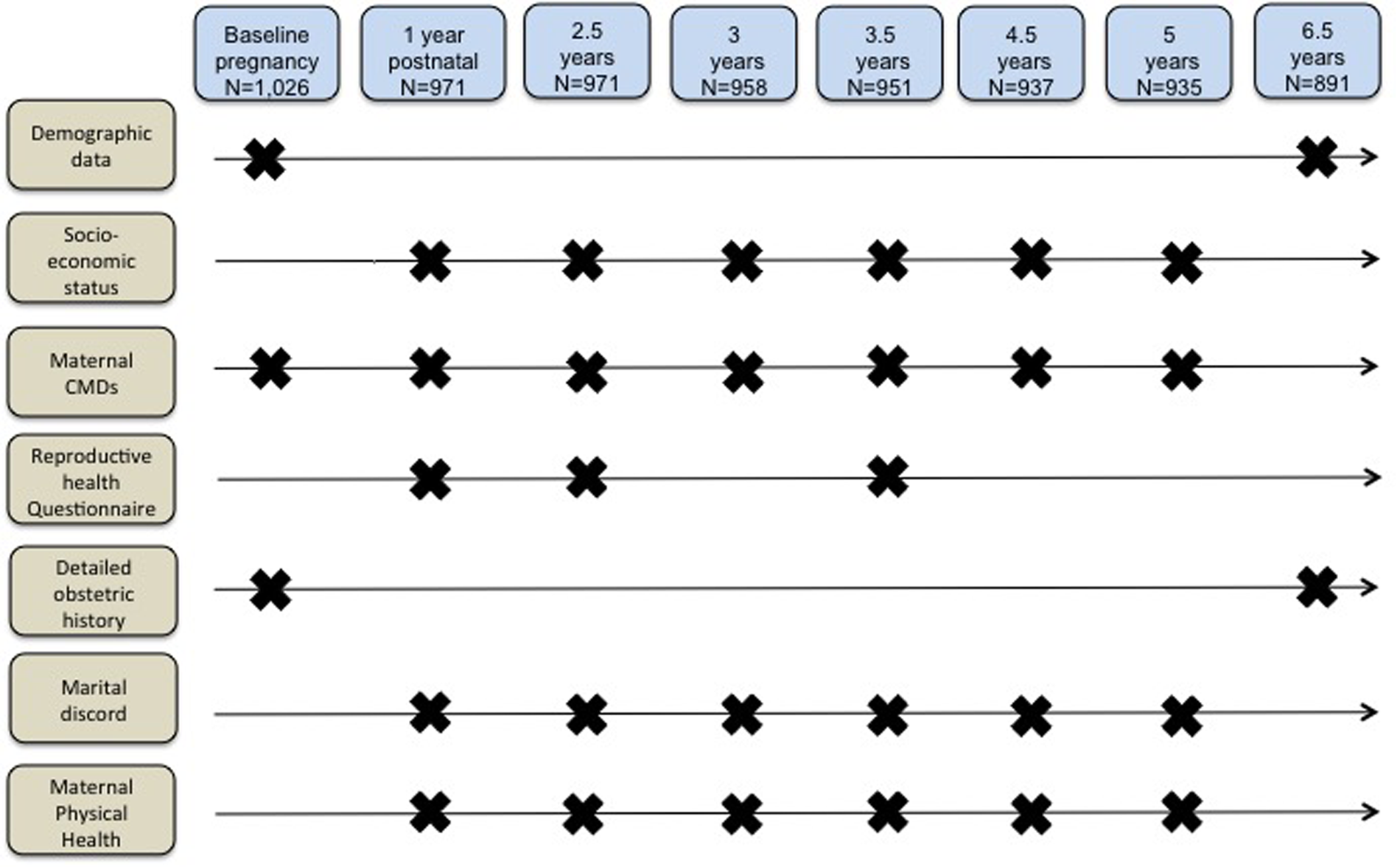

This cohort study is part of the C-MaMiE project (Child health, growth and development in relation to maternal mental disorder in Ethiopia), a population-based sample of 1065 pregnant women recruited between July 2005 and March 2006 (Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Medhin, Alem, Tesfaye, Lakew, Worku, Dewey, Araya, Abdulahi, Hughes, Tomlinson, Patel and Prince2009a, Reference Hanlon, Whitley, Wondigmagegn, Alem and Princeb) and followed up at 12 months postpartum, 2.5 years and at regular intervals of 6–12 months up to 6.5 years (Fig. 1). The primary aim of the project was to evaluate the public health impact of maternal CMD upon infant and child outcomes; this study was a hypothesis-driven secondary analysis.

Fig. 1. Assessment time-points.

Study setting

The study was situated in the health and demographic surveillance site (HDSS) at Butajira, a predominantly rural area of Ethiopia located 130 km south of the capital city, Addis Ababa, in the Gurage Zone, Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR) of Ethiopia (Berhane et al., Reference Berhane, Wall, Kebede, Emmelin, Byass, Muhe, Andersson, Deyessa, Högberg, Gossaye, Alem and Dahlblom1999). Fertility levels in this region remain high, with a total fertility rate of 4.4 births per woman in 2016 (CSA Addis Ababa and ICF, 2016), compared to 5.6 in 2005, at the time of the start of our study (CSA Addis Ababa and ORC Macro, 2006). Modern contraceptive use in SNNPR was estimated to be 11.9% in 2005, which has increased to 44.6% among married women age 14–49 years in 2019 (EPHI and ICF, 2019). Over the past decade, the Ethiopian government has invested in the Health Extension Programme (HEP) with a strong emphasis on improving rural health care services by task sharing and capacity building (Ethiopia FMOH, 2012a). Two female health extension workers (HEWs), who receive 1 year of training on 16 essential health packages including maternal and child health, family planning and adolescent reproductive health, staff health posts serving a population ranging from 3000 to 5000 in a village (kebele) (Ethiopia FMOH, 2005). The programme has a strong community focus. HEWs spend a substantial amount of time on home visits and train model families on HEP health packages so these households are able to implement their knowledge and influence neighbours to adopt these practices (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Tesfaye, Ramana and Chekagn2016).

Study participants

For the original cohort, eligible women were between the ages of 15 and 49 years, able to converse in Amharic (the national language of Ethiopia), living in the HDSS and in the third trimester of pregnancy during the study recruitment period (Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Medhin, Alem, Tesfaye, Lakew, Worku, Dewey, Araya, Abdulahi, Hughes, Tomlinson, Patel and Prince2009a, Reference Hanlon, Whitley, Wondigmagegn, Alem and Princeb). For the current study, we restricted our data analysis to women aged between 15 and 38 at recruitment so that all would be within the reproductive window throughout the study period [n = 1026 (96.3% of original cohort)]. The women were identified by the Butajira Rural Health programme (BRHP) enumerators in the course of their 3-monthly surveillance interviews and, after giving informed consent, were interviewed by the project data collectors (Berhane et al., Reference Berhane, Wall, Kebede, Emmelin, Byass, Muhe, Andersson, Deyessa, Högberg, Gossaye, Alem and Dahlblom1999).

Measures

Maternal CMDs

Maternal CMD was measured at baseline, 12 months postpartum and at five other time points up to 6.5 years post-recruitment (Fig. 1) using Self-Reporting Questionnaire, 20-item version (SRQ-20). The SRQ is a 20-item scale that asks about depressive, anxiety and somatic symptoms present in the preceding month, generating a continuously distributed scale score indicating the level of overall psychological morbidity. The SRQ-20 was extensively validated for use in a mixed sample of pregnant and postnatal women in the Butajira population (Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Medhin, Alem, Araya, Abdulahi, Hughes, Tesfaye, Wondimagegn, Patel and Prince2008).

Reproductive health behaviours and pregnancy

The project data collectors administered a reproductive health questionnaire at 12 months, 2.5 years and 3.5 years post baseline (Fig. 1). The questionnaire covered questions on current pregnancy status, pregnancy spacing intentions, knowledge of specific contraceptive methods, current use and reasons for not using contraception. Detailed parity information was collected at baseline and at 6.5 years. Number of pregnancies per woman during this cohort study was calculated by subtracting initial parity from total number of pregnancies reported at 6.5 years.

Unmet need for family planning

We adapted the definitions of unmet need for contraception from the Guide to DHS Statistics (Croft et al., Reference Croft, Marshall, Allen, Arnold, Assaf and Balian2018). Unmet need for limiting was defined as the percentage of women who reported they did not want to have more children and were neither pregnant nor using contraception at the time. Unmet need for spacing was operationalised as the percentage of women not using contraception and not pregnant who answered they would like to wait 2 years or more for the next pregnancy. At each time point, some women were pregnant but reported they did not want to be pregnant. Their numbers have been presented as a separate column in the unmet need for contraception. Women pregnant due to contraceptive failure were not included. Total unmet need for family planning was, therefore, defined as the proportion of women who were not pregnant and wanted to postpone their next birth for 2 or more years or stop childbearing altogether, but were not using a contraceptive method or had a mistimed or unwanted current pregnancy.

The denominator for unmet need was the total number of women completing the reproductive health questionnaire in each cohort time point. A further condition for unmet need is that women are fertile. All women in our cohort were in their third trimester of pregnancy at recruitment and their upper age limit was restricted to 38 years.

Confounders

Confounders were selected on the basis of published evidence (CSA Addis Ababa and ICF, 2016). Socio-demographic variables including age, marital status, religion, maternal and paternal educational level were collected at baseline.

A composite variable measuring socio-economic status (SES) was created by adding the following poverty indicators: self-reports of indebtedness, hunger in the last month and perceived lower relative wealth (Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Medhin, Alem, Tesfaye, Lakew, Worku, Dewey, Araya, Abdulahi, Hughes, Tomlinson, Patel and Prince2009a, Reference Hanlon, Whitley, Wondigmagegn, Alem and Princeb). This was measured at baseline and at five other time points. The number of times the woman reported two or more poverty indicators was calculated across the sample.

Similarly, marital discord was indicated through self-report that (i) the husband was not providing enough help, (ii) the relationship was ‘average, bad or very bad’, (iii) they sometimes or often quarrelled or (iv) the woman felt that her husband drank too much alcohol (Servili et al., Reference Servili, Medhin, Hanlon, Tomsinson, Worku, Baheretibeb, Dewey, Alem and Prince2010). Poor physical health was defined as a self-reported episode of malaria, diarrhoea or fever measured for the 6 months preceding each time point (Smartt et al., Reference Smartt, Medhin, Alem, Patel, Dewey, Prince and Hanlon2016). The number of time points with the described measures were added across the whole sample (Fig. 1).

Analyses

Stata version 15 software was used for data analysis (StataCorp, 2017). The initial analysis strategy was hypothesis-driven, using logistic regression to investigate the association between (1) CMD symptoms (SRQ20 as continuous variable) at 12 months upon total unmet need for family planning as defined above at 2.5 years and between (2) CMD symptoms (SRQ 20 as continuous variable) at 3 years and unmet need for contraception at 3.5 years. We separated the analyses for these time points because the time interval between exposure and outcome was different and there could be different patterns of associations over the time since the index pregnancy. These hypotheses were partially and fully adjusted to confounders identified a priori, including demographic and socio-economic characteristics. A further exploratory model calculated crude and adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for the effect of these other variables on unmet need for contraception.

In addition, simple and multiple Poisson regression was used to test the hypothesis that maternal CMD would be associated with higher number of cumulative pregnancies during the project follow-up period. A fully adjusted exploratory model calculated incidence rate ratios (IRRs) with the corresponding confidence intervals (CIs) for the effects of other variables, including contraceptive use, socio-demographic and obstetric factors on the number of pregnancies the during study period. Missing data were addressed by case-wise deletion.

Results

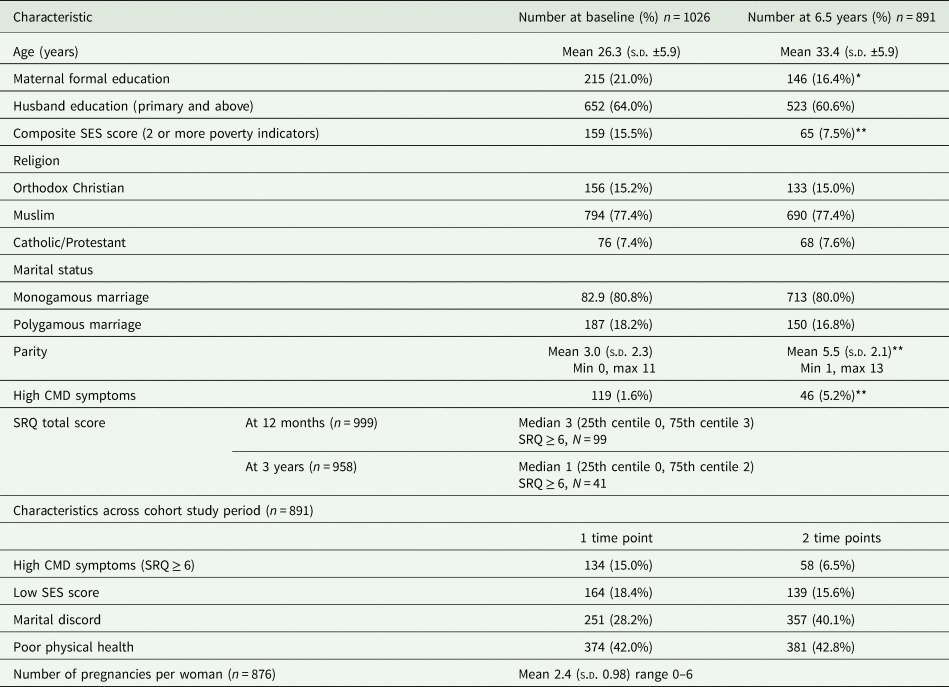

Follow-up rates were 94.6% (n = 971) at 2.5 years, 92.7% (n = 951) at 3.5 years and 86.8% (n = 891) at 6.5 years (Fig. 1). Women who were lost to follow-up did not differ by age, religion or husband's education, but were less likely to have formal education and more likely to have a lower socio-economic score and higher CMD symptoms at baseline (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of the cohort

Significant difference between characteristic at baseline and 6.5 years.

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Mean maternal age for women at time of recruitment into the study was 26.3 years (s.d. ±5.9) at baseline and almost all women were married (99.0%), with 18.2% at baseline and 16.8% at 6.5 years in a polygamous marriage. Only 21.0% of women at the time of the index pregnancy had formal education, whereas over 50% of husbands had attended primary school or above. Over two-thirds of women were Muslim. At baseline mean parity was 3.0 (s.d. ±2.3) whereas at 6.5 years parity was 5.5 (s.d. ±2.1).

Two or more poverty indicators were endorsed by 15.6% women at two or more time points. Marital discord was reported by 40.1% of women at two or more time points and 42.8% reported recent poor health at two or more time points (Table 1).

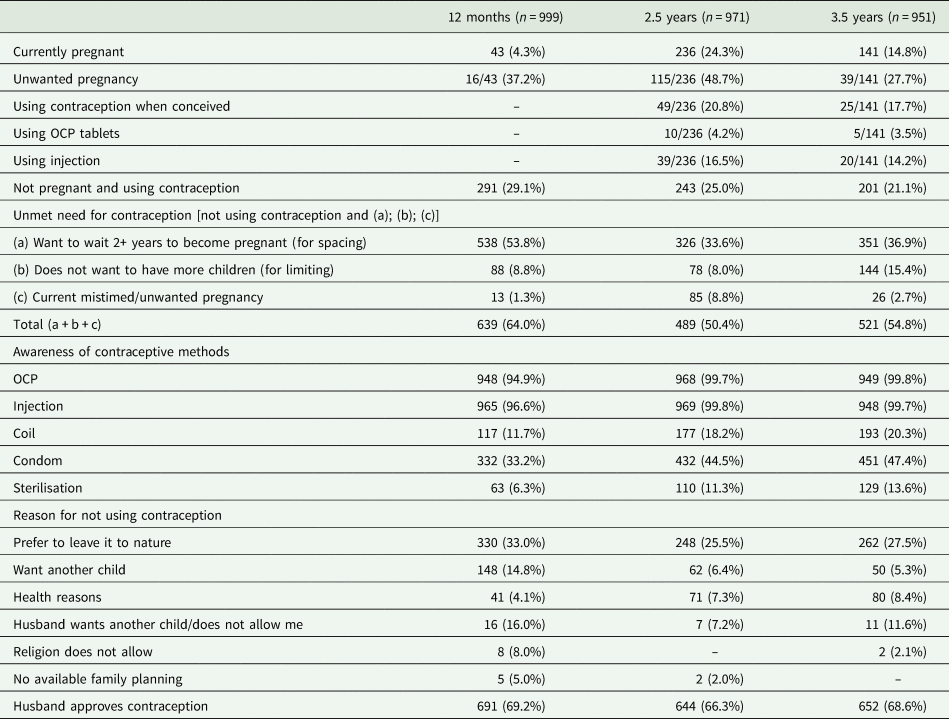

High levels of CMD symptoms (SRQ ≥ 6) were experienced by 15.0% of women at one time point and 6.5% at two or more time points during the follow-up period. At 1 year postnatal, 43 women (4.3% of total sample) were pregnant again. At 2.5 years and 3.5 years, 24.3 and 14.8% of women reported current pregnancy, respectively. Of these, 37.2% at 12 months, 48.7% at 2.5 years and 27.7% at 3.5 years were unwanted pregnancies and 20.8% at 2.5 years and 17.7% at 3.5 years were due to contraceptive failure (Table 2). Some women became pregnant while using a long-acting modern contraceptive such as injection: 16.5% of all pregnancies at 2.5 years (n = 39); 14.2% of all pregnancies at 3.5 years (n = 20).

Table 2. Reproductive health questions (number of affirmative answers/total sample)

Unmet need for contraception

Less than one-third of women reported current use of contraception at each of the time points. Unmet need for spacing was higher at 12 months, with over half of women (n = 538, 53.8%) not using contraception and wanting to wait for 2 or more years before the next pregnancy. Unmet need for contraception for limiting was higher at 3.5 years when 206 women (21.6%) reported not wanting to have more children. Total rates of unmet need for contraception were calculated to be 64.0% at 12 months, 53.1% at 2.5 years and 62.7% at 3.5 years (Table 2).

Most women were familiar with modern contraceptive methods and over 95% of women knew about the oral combined pill and long-acting injectables. Less than half reported familiarity with condoms. The most commonly reported reasons for not using contraception was a preference to leave it to nature (33.0% at 12 months, 25.5% at 2.5 years and 27.5% at 3.5 years). Only a very small proportion reported not using contraception for religious reasons or lack of access (<5%). More than two-thirds of women reported that their husbands approved of contraception.

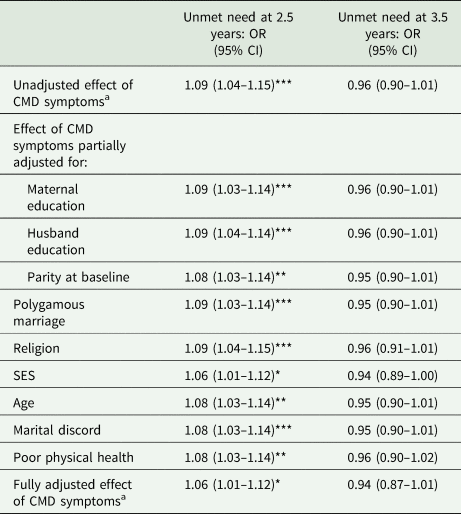

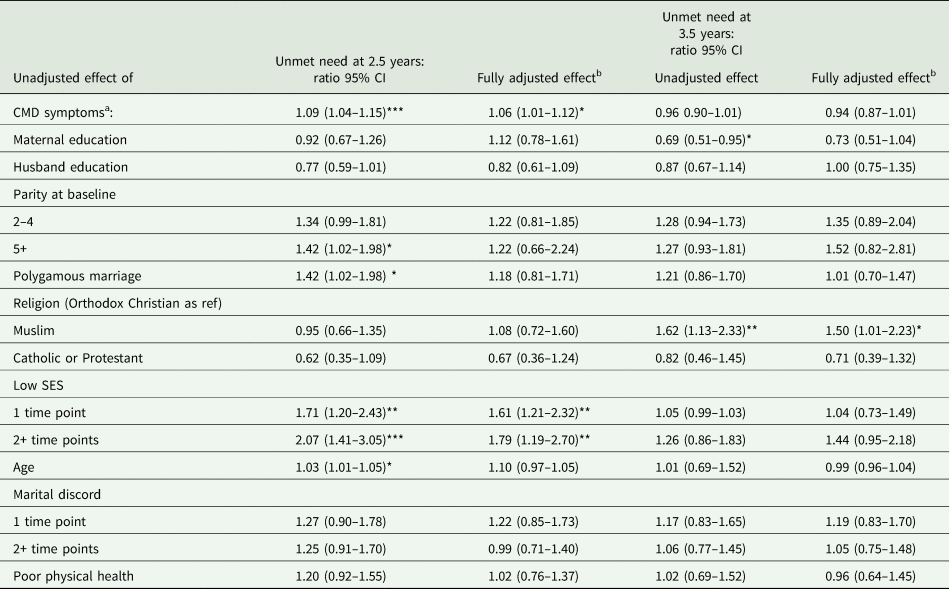

Effect of CMD symptoms on unmet need for contraception

CMD symptoms were higher at 12 months (median SRQ score 3, 25th centile 0, 75th centile 3, n = 99) than at 3 years (median SRQ score 1, 25th centile 0, 75th centile 2, n = 41) and other subsequent points in the study period. Higher levels of CMD symptoms at 12 months post-index pregnancy were associated with higher levels of unmet need for contraception at 2.5 years in both the crude (OR 1.09; 95% CI 1.04–1.15 for every 1 point increase in SRQ score) and fully adjusted hypothesis-driven models (aOR 1.06; 95% CI 1.01–1.12), including potential confounders of maternal and husband education, SES, age, parity at baseline and religion. However, higher levels of CMD symptoms at 3 years were not associated with unmet need for contraception at 3.5 years in either the unadjusted or adjusted model (Table 3).

Table 3. Hypothesis-driven model of the effect of CMD symptoms on unmet need for family planning at 2.5 and 3.5 years

a CMD symptoms at 12 months for 2.5 year model and at 3 years for the 3.5 year model.

*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001.

In the fully adjusted exploratory model, only CMD symptoms and lower SES (OR 1.79; 95% CI 1.19–2.70) continued to be significant (Table 4).

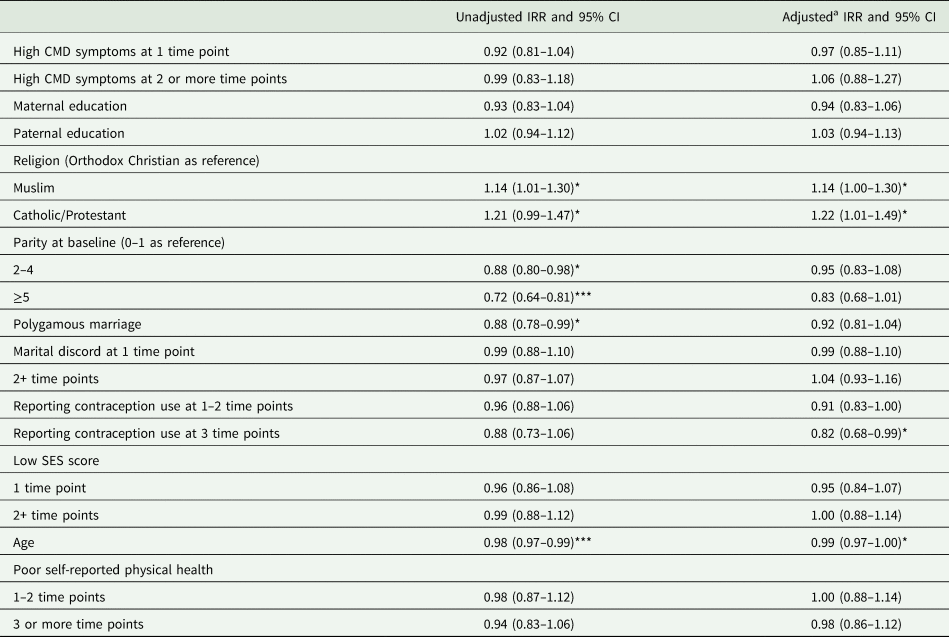

Table 4. Multivariable model for factors associated with cumulative number of pregnancies during study period

*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001.

a Adjusted model = multiple Poisson regression with all variables included.

Cumulative number of pregnancies

During the 6.5 year follow-up period the mean number of pregnancies per woman (n = 876) was 2.4 (s.d. 0.98), ranging from 0 to 6 pregnancies (Table 2). There was no association between maternal CMD and number of pregnancies over the follow-up period in either the univariate or multivariable models [adjusted IRR (adj IRR) 0.97; 95% CI 0.85–1.11 for high CMD at one time point, aOR 1.06; 95% CI 0.88–1.27 at two or more time points]. In the fully adjusted multivariable model, consistent use of contraception led to a decrease of 18% in the number of pregnancies (adj IRR 0.82; 95% CI 0.68–0.99), and the effect of age was a decrease of 1% per year (adj IRR 0.99; 95% CI 0.97–1.00) (Table 5).

Table 5. Exploratory model for factors affecting unmet need for family planning at 2.5 and 3.5 years

a CMD symptoms at 12 months for 2.5 year model and at 3 years for the 3.5 year model.

b Fully adjusted model includes all factors in the table.

*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001.

Discussion

Main findings

In our study we found that high CMD symptoms at 1 year postnatal were associated with higher unmet contraceptive need at 2.5 years. This result was significant even after adjusting for other confounders known to traditionally impact adoption of modern contraception including maternal education, SES, parity and age (Tadele et al., Reference Tadele, Abebaw and Ali2019). An association was not seen between high CMD symptoms at 3 years and unmet contraceptive need at 3.5 years. There was also no association between CMD symptoms and number of pregnancies during the follow-up period.

We also found that unmet need for contraception was high in rural Ethiopia (range 56.3–64.0% in our cohort), particularly in the first year post-delivery (Borda and Winfrey, Reference Borda and Winfrey2010 ; Tegegn et al., Reference Tegegn, Arefaynie and Tiruye2017). Our findings also highlight the dynamic nature of women's reproductive needs over time. Although at 12 months post recruitment the larger amount of need was for spacing (53.8%), the number of mistimed and unwanted pregnancies peaked at 2.5 years (11.5%) and the need for limiting increased at 3.5 years (15.4%) compared to the two previous time points. Importantly, around one-fifth of women became pregnant despite adoption of modern contraception (20.8% at 2.5 years and 17.7% at 3.5 years).

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of our study include the large, representative sample of women from a rural setting in a low-income country, the use of locally validated measures of CMD and the prospective design with high rates of follow-up. Although previous studies have focused on child outcomes, the impact of CMDs on women's health behaviours has been largely neglected in published literature. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first from a low-income country to examine impact of mental health on reproductive behaviours, with potential generalisability to other similar settings. Our study also has several potential limitations. There was differential attrition of women with higher baseline CMD and poverty. We expect that the association between maternal CMD and family planning might be higher in this group, although it is not possible to know the direction of any selection bias. Data collection for our cohort spanned from 2005 to 2012, which preceded the latest DHS survey of 2019, and therefore would not have captured the increase in contraceptive use that has occurred in the last few years. The observed association may, therefore, have changed as mental health interacts with different emerging barriers to uptake of family planning. However, our expectation is that women's mental health will become more salient as more structural barriers to access diminish in importance.

Our study is limited by the reliance on self-reported data for outcomes such as use of contraception and number of pregnancies which may be subject to reporting bias. We also lacked data on women's menstruation status therefore we cannot exclude women who are postpartum amenorrhoeic or menopausal at later cohort points from our unmet need calculations. However, our first collection point for reproductive health questions was 12 months post-partum and lactation amenorrhoea as a contraceptive method should not be considered effective more than 6 months post-delivery (Kennedy and Visness, Reference Kennedy and Visness1992; Van der Wijden and Manion, Reference Van der Wijden and Manion2015). Evidence from other rural regions of the country showed an important reason for women not using contraception in the late postpartum period is the erroneous belief that they are not a risk of pregnancy if their periods have not returned (Tegegn et al., Reference Tegegn, Arefaynie and Tiruye2017; Embafrash and Mekonnen, Reference Embafrash and Mekonnen2019). In order to avoid capturing women that may become menopausal during the study we restricted upper age of cohort to 38 years. Mean age for menopause is 51 globally however there are large geographical differences (Melby et al., Reference Melby, Lock and Kaufert2005). There is limited data on average age of menopause in Ethiopia but regional studies have reported it to be around 42.5 years (Yisma et al., Reference Yisma, Eshetu, Ly and Dessalegn2017) and 45.3 years (Kibret and Mariam, Reference Kibret and Mariam2019), therefore lower than in other nations.

For the contraceptive outcomes, the CMD exposure does not capture the longitudinal course of mental ill-health. In the analysis of CMD in relation to subsequent pregnancies, exposure to CMD over time is captured through measurement at repeated time points, but we do not have data to investigate the effect of CMD in the perinatal period v. at other times on subsequent pregnancies. Also, we cannot exclude that other confounders not used in our models which may play a significant role in our hypotheses. For example, we lacked data on breastfeeding which may be an important mediator in some of the associations studied. We also did not use a standardised and validated measure of social support. However, previous qualitative study with this cohort indicated that the most important source of support for women is from their partner (Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Medhin, Alem, Tesfaye, Lakew, Worku, Dewey, Araya, Abdulahi, Hughes, Tomlinson, Patel and Prince2009a, Reference Hanlon, Whitley, Wondigmagegn, Alem and Princeb) and we therefore adjusted for marital discord. We were unable to explore reasons behind contraceptive failure in our sample. We also lacked information about what other medications, including psychotropic medication, the women may be receiving. However, it is expected that psychotropic medication would be very rarely accessed by study participants given the non-availability of appropriate services at the time when the study was conducted.

Implications

With the ongoing global efforts to mitigate unmet need for family planning we believe our results provide important evidence to support integration of mental health and physical health services as well as identification of vulnerable populations that are hard to reach within the current models of care. Studies from high-income countries and mostly from clinic-based samples have previously highlighted an association between depression and/or stress and contraceptive non-use and use of less effective methods (Garbers et al., Reference Garbers, Correa, Tobier, Blust and Chiasson2010; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Moreau, Trussell and Barber2013a, Reference Hall, Moreau, Trussell and Barberb). In those settings, suggested mechanisms underlying this association are that psychological distress may negatively impact the decision making and risk assessment abilities of women with regards to contraceptive behaviour (Yuen and Lee, Reference Yuen and Lee2003; Hall, Reference Hall2012). An alternative possible mechanism is that women with CMD symptoms may be more susceptible to perceive somatic side effects of hormonal contraception and therefore discontinue use more readily (Hall et al., Reference Hall, White, Rickert, Reame and Westhoff2012). Conversely, recent evidence from a high-income country also suggests women who develop postpartum psychiatric disorders are less likely to go on to have further children (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Plana-Ripoll, Ingstrup, Agerbo, Skjærven and Munk-Olsen2020). We did not find any studies examining the effect of symptoms of depression and anxiety on family planning or fertility in low- or middle-income country settings. Contextual differences may mean that other mechanisms underlie the association between mental health and family planning. In the rural, low-literacy setting of this study, there are many structural barriers to accessing family planning, in particular due to low SES and low empowerment of women. Poorer mental health in a woman may lead to social withdrawal, decreased exposure to health education messages and diminished motivation or capacity to mobilise support to access family planning services. Although an association was found between CMD symptoms at 12 months and unmet need for contraception at 2.5 years, no significant association was found for CMD symptoms at 3 years and unmet need at 3.5 years or between CMD symptoms and number of pregnancies during the study period. Therefore, the relationship between CMD symptoms and adoption of family planning may have a temporal element and be affected by the stage of a woman's reproductive life. Further studies are required to explore these potential mechanisms and inform intervention development.

Our results highlight a need to take a more holistic and person-centred approach to family planning services, including the identification and support of women experiencing psychosocial distress. The World Health Organization mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) seeks to integrate mental health care into all general health care services (WHO, 2008). Although this should include family planning services, there has been limited consideration of the importance of mental health in this area to date. The Ministry of Health of Ethiopia has been supporting integration of services into primary care by issuing a National Mental Health Strategy (Ethiopia FMOH, 2012b) based around mhGAP (WHO, 2013). In addition, mental health is now one of the packages of care for level IV HEWs (Tilahun et al., Reference Tilahun, Hanlon, Araya, Davey, Hoekstra and Fekadu2017). However, the extent to which HEWs are implementing mental health care is limited by a lack of integration of mental health into supervision structures or the health management information system (Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Eshetu, Alemayehu, Fekadu, Semrau, Thornicroft, Kigozi, Marais, Petersen and Alem2017). Effective brief psychological treatments have been developed for CMD symptoms in LMICs and most of these are delivered by community health workers and have been developed for women (Singla et al., Reference Singla, Kohrt, Murray, Anand, Chorpita and Patel2017). The HEP in Ethiopia with its strong community focus and delivery of home visits by female HEWs would, therefore, be well equipped to identify women who might be experiencing mental health symptoms and would benefit from these interventions but may not access other parts of the health system.

Conclusion

To our knowledge this was the first study to investigate the impact of poor mental health on unmet need for contraception and fertility rate in a rural sample of women from a lower income country. We showed that high level of CMD symptoms at 1 year postpartum is associated prospectively with higher unmet need for contraception independently of SES and educational status. There is a lack of models of care promoting integration of mental and physical health in the family planning setting and further research is necessary to study the burden of preconception mental disorders and how these can be best addressed.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset included for the analyses within this manuscript can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the women who participated in the study for generously giving their time and energy to complete interviews, and the staff of the Butajira Rural Health Programme for their kind co-operation.

Financial support

C-MaMiE cohort study and open access to this paper was funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant numbers: 071643, 081504 and 093559). MP and CH are funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research Unit on Health System Strengthening in Sub-Saharan Africa, King's College London (GHRU 16/136/54) using UK aid from the UK Government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. CH receives support from AMARI as part of the DELTAS Africa Initiative [DEL-15-01].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests. Full disclosure of interests available to view online as supporting information.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was obtained from the National Ethical Review Committee for Ethiopia and the Research Ethics Committee of King's College London in the UK. Written, informed consent was obtained for all women. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.