If there can be ‘no health without mental health’ (Prince et al. Reference Prince, Patel, Saxena, Maj, Maselko, Phillips and Rahman2007), then a health system does not function properly if it cannot protect and take care of the basic health rights and needs of people who are unwell or vulnerable – including people with mental illness (Chisholm et al. Reference Chisholm, Flisher, Lund, Patel, Saxena, Thornicroft and Tomlinson2007). In most low- and middle-income countries (LAMICs), resources and services for mental health are meagre in the extreme, with low-income countries allocating on average 0.5%, and lower-middle income countries 1.9% of their health budget to the treatment and the prevention of mental disorders, even though they represent over 10% of the overall disease burden (Saxena et al. Reference Saxena, Thornicroft, Knapp and Whiteford2007; World Health Organization, 2011). In LAMICs, there is on average one psychiatrist per 1.7 million inhabitants and one psychiatric inpatient bed per 42 000 inhabitants (Jacob et al. Reference Jacob, Sharan, Mirza, Garrido-Cumbrera, Seedat, Mari, Sreenivas and Saxena2007). Most of the funds that are made available by governments are directed towards the running costs of mental hospital service provision. This limits the development of more equitable and cost-effective community-based services. The result of inadequate, inequitable and inefficient resourcing for mental health is a substantial treatment gap (Thornicroft, Reference Thornicroft2007). An international survey supported by WHO showed that 76–85% of people with severe mental disorders in low-income countries had not received any treatment in the previous 12 months (Demyttenaere et al. Reference Demyttenaere, Bruffaerts, Posada-Villa, Gasquet, Kovess, Lepine, Angermeyer, Bernert, de Girolamo, Morosini, Polidori, Kikkawa, Kawakami, Ono, Takeshima, Uda, Karam, Fayyad, Karam, Mneimneh, Medina-Mora, Borges, Lara, Ormel, Gureje, Shen, Huang, Zhang, Alonso, Haro, Vilagut, Bromet, Gluzman, Webb, Kessler, Merikangas, Anthony, Von Korff, Wang, Brugha, Guilar-Gaxiola, Lee, Heeringa, Pennell, Zaslavsky, Ustun and Chatterji2004). The adverse consequences of this unmet need include the violation or abuse of human rights (Callard et al. Reference Callard, Sartorius, Arboleda-Florez, Bartlett, Helmchen, Stuart, Taborda and Thornicroft2012), long-term disability and ill-health (Chisholm et al. Reference Chisholm, Van Ommeren, Ayuso-Mateos and Saxena2005), and increased mortality (Thornicroft, Reference Thornicroft2011; Wahlbeck et al. Reference Wahlbeck, Westman, Nordentoft, Gissler and Laursen2011).

It is therefore clear that the quantity and quality of mental health care in LAMICs are grossly deficient. Is there sufficient relevant evidence from LAMICs on cost-effective interventions that do need to be put into practice? To date much of the mental health research undertaken in LAMICs has been on classification, epidemiology and identification of mental disorders. Yet recent developments include improved policy guidance, treatment guidelines and generation of evidence on the cost-effectiveness of interventions in LAMICs, especially those relevant for primary and community care staff (Patel & Thornicroft, Reference Patel and Thornicroft2009). Accordingly, the knowledge base for what to do about the escalating burden of mental disorders has improved significantly over the last decade (World Economic Forum, 2011). Landmark developments include the World Health Report in 2001 (World Health Organization, 2001), two Lancet series on global mental health in 2007 and 2011, the establishment of a Global Movement for Mental Health, the development of WHO's mhGAP programme for scaling up services for mental, neurological and substance use disorders (complete with its evidence-based intervention guide) (Barbui et al. Reference Barbui, Dua, Van Ommeren, Yasamy, Fleischmann and Clark2010; World Health Organization, 2010; Dua et al. Reference Dua, Barbui, Clark, Fleischmann, van Ommeren, Poznyak, Yasamy, Thornicroft and Saxena2011), and the recent Grand Challenges in Global Mental Health review (Collins et al. Reference Collins, Patel, Joestl, March, Insel, Daar, Anderson, Dhansay, Phillips, Shurin, Walport, Ewart, Savill, Bordin, Costello, Durkin, Fairburn, Glass, Hall, Huang, Hyman, Jamison, Kaaya, Kapur, Kleinman, Ogunniyi, Otero-Ojeda, Poo, Ravindranath, Sahakian, Saxena, Singer and Stein2011), which singled out improved treatment and access to care as the core agenda for future research and development efforts. There is therefore now a strong and growing international consensus that the shortage of specialist mental health care staff requires a policy shift to a clear commitment that LAMICs horizontally integrate mental health care into primary care and into maternal health care (Eaton et al. Reference Eaton, McCay, Semrau, Chatterjee, Baingana, Araya, Ntulo, Thornicroft and Saxena2011; United Nations, 2011). Such integration now also provides opportunities for reducing the stigma of mental illness, which in itself is a major barrier to accessing care and to social inclusion (Thornicroft et al. Reference Thornicroft, Brohan, Rose, Sartorius and Leese2009).

The problem is how to translate this body of knowledge into practice. At its root these are health systems issues. Past failures have been partly due to a shortage of political will and funding, and also reflect a technical set of challenges around how best to address health system issues and constraints as they relate to integrated mental health service provision in non-specialized settings, including human resources and capacity building, information systems, health financing and service delivery (Saraceno et al. Reference Saraceno, van Ommeren, Batniji, Cohen, Gureje, Mahoney, Sridhar and Underhill2007).

The recently developed World Health Organization mhGAP Intervention Guide therefore offers a step change opportunity to practitioners in LAMICs with its practical guidance on the identification and treatment of mental disorders in primary and community care settings. The fundamental public health questions are: (i) can such guidelines be put into practice in routine clinical settings, (ii) if so, do they confer patient benefit and (iii) does their use contribute to an increase in the treated prevalence rate for specified conditions?

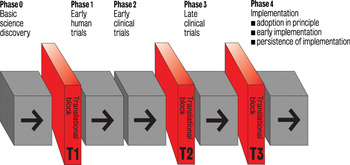

It is clear from over two decades of research that the creation of guidelines is necessary but not sufficient for evidence-based practice, whether in high- or low-income settings. As a consequence there has been the recent rapid development of ‘implementation science’ (Madon et al. Reference Madon, Hofman, Kupfer and Glass2007; Eccles et al. Reference Eccles, Armstrong, Baker, Cleary, Davies, Davies, Glasziou, Ilott, Kinmonth, Leng, Logan, Marteau, Michie, Rogers, Rycroft-Malone and Sibbald2009), with some applications in the field of mental health (Bauer, Reference Bauer2002; Michie et al. Reference Michie, Pilling, Garety, Whitty, Eccles, Johnston and Simmons2007; Evans-Lacko et al. Reference Evans-Lacko, Jarrett, McCrone and Thornicroft2010). A recent review has summarized the factors that have been identified as facilitators or barriers to the implementation of mental illness-related clinical guidelines (Tansella & Thornicroft, Reference Tansella and Thornicroft2009) and distinguished between: (i) the adoption in principle of guidelines; (ii) early implementation and (iii) their sustained use over time, namely actions at Phase 4 as shown in Fig. 1 (Thornicroft et al. Reference Thornicroft, Lempp and Tansella2011).

Fig. 1. Five phases and three blocks in the translational medicine continuum. (Thornicroft et al., 2011)

The two critical needs are clear. First, well designed, sufficiently statistically powered, properly conducted, and openly reported intervention studies (including randomized controlled trials) of interventions (at both the patient/practitioner and at the clinical team/facility level), which are utterly realistic and practical in low- and middle-income settings. This requires immediate investment from research funding councils and donors in high-income countries. When this evidence base is in place then mental health service provision in LAMICS can be based on information that is fit for the purpose. Until then using the limited information that has been directly derived from LAMCs, along with the unsatisfactory proxy of adapting evidence from high-income settings, is the least bad basis for action. Second, there a requirement to understand more clearly how and why guidelines can be implemented in low-and medium-income settings so that clinical practice is more often based on relevant evidence that does lead to patient benefit.

Acknowledgements

G.T. is funded in relation to a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Programme grant awarded to the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (GT), and in relation to the NIHR Specialist Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre at the Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London and the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. All opinions expressed here are solely those of the author. The author would like to acknowledge the contribution of Professor Michele Tansella towards this approach to implementation science.

Conflicts of Interest

None.