INTRODUCTION

Shortly after the discovery of antimicrobials and their introduction into clinical practice, acquired antimicrobial resistance was observed to adversely impact clinical outcomes [Reference Forbes1]. As antimicrobial resistance threatens the efficacy of antimicrobial treatment for bacterial infections in any animal species, it is a topic of much research in the human, veterinary, agri-food and environmental sectors. The epidemiology of antimicrobial resistance is complex and involves links between humans, animals and the environment, including the transmission of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria within and between these niches. Public health concerns about the transmission of antimicrobial resistant foodborne pathogens or genes through the food chain have existed for decades. These concerns continue with the isolation of extended-spectrum cephalosporin- [Reference Seiffert2] and carbapenem-resistant [Reference Seiffert2–Reference Woodford4] E. coli and Salmonella enterica in livestock.

Human acquisition of bacteria carrying antimicrobial resistance genes from cattle and other farmed animals may occur by direct animal contact, via the food chain, or through contamination of the environment. Consumption of beef products has been linked to foodborne outbreaks of infection including those caused by antimicrobial-resistant bacteria [Reference Varma5]. Infection with antimicrobial-resistant organisms has been associated with more adverse health outcomes compared to infection with pan-susceptible strains. For example, patients with antimicrobial resistant Salmonella were at greater risk of hospitalization, increased duration of hospitalization and bloodstream infections [Reference Varma5]. Because of the adverse human health outcomes and the emergence of resistance in animals and food to antimicrobials of notable public health importance [Reference Seiffert2, Reference Woodford4], determining modifiable factors or interventions to reduce the occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in cattle populations is desirable.

Antimicrobial resistance is a broad, widely researched topic with a large volume of peer-review published research. Links between antimicrobial uses in agriculture with antimicrobial resistance in human health have been documented [Reference Hummel, Tschape and Witte6–Reference Otto14]. Consequently, some interventions that focus on reduction of antimicrobial use have been applied in certain agricultural settings to mitigate the transfer of antimicrobial resistant bacteria or determinants along the food chain [Reference Cheng11, 15]. However, modifiable non-antimicrobial factors or interventions may also contribute to a reduction in the transfer of resistant bacteria or determinants and a reduction in the occurrence of antimicrobial resistance. Modifiable non-antimicrobial factors are factors other than antimicrobial use or exposure that may be changed to alter the occurrence of antimicrobial resistance such as type of production system (conventional or non-conventional), stocking density and hygiene. The relationships of non-antimicrobial factors to antimicrobial resistance may be direct, but likely also have relationships with illness, antimicrobial treatment and use, other routes of antimicrobial exposure and each other. Modifying non-antimicrobial factors may impact the occurrence of antimicrobial resistance through more than one causal pathway. A structured synthesis of published research is required to more fully understand the current state of knowledge, to identify plausible and practical non-antimicrobial interventions, and to identify and prioritize research needs and knowledge gaps.

The scoping review is a newer method of review with over 70% of scoping reviews in the health sector published since 2010 [Reference Pham16]; notably, they have also been employed in the agri-food research arena [Reference Wilhelm17–Reference Tusevljak19]. Scoping review methodologies are appropriate for the review of broad topics [Reference Arksey and O'Malley20] and they can be used to map the distribution and characteristics of a particular topic or issue, summarize the state of knowledge, identify research gaps and inform future research, provide data to stakeholders, and help prioritize questions for more focused systematic review [Reference Arksey and O'Malley20]. Our research question was: What modifiable non-antimicrobial factors or interventions have the potential to decrease the prevalence of organisms with phenotypic or genotypic expression of resistance, to decrease the populations of organisms carrying resistance genes, or to prevent the accumulation of resistance (i.e. reduce selection pressure for resistance) in North American cattle production systems? The scoping review approach was a better fit to our broad research question than the more focused systematic review method. We searched for, and reviewed, published peer-reviewed English-language literature (without geographical limitations) covering animal populations with additional data arising from human populations and in vitro studies to identify, characterize, and summarize potential modifiable non-antimicrobial interventions in order to reduce the occurrence of antimicrobial resistance among enteric bacteria in North American cattle populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search terms and strategy

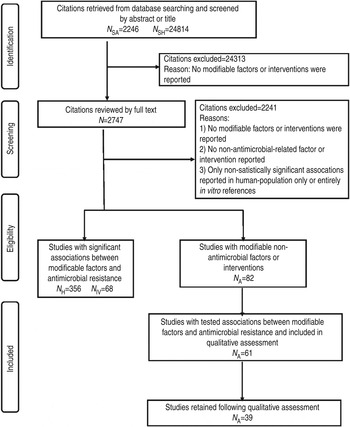

Using the research question stated above, searches were developed to return citations of investigations into non-antimicrobial factors associated with antimicrobial resistance in animal populations, human populations and in vitro (Fig. 1). For animal population citations, the search focused on antimicrobial resistance in enteric or faecal bacteria and used multiple broad and specific search terms for antimicrobial susceptibility and animal population (Supplementary Appendix 1, available online). This search used eight databases in the OVID platform (Medline, EMBASE, CAB abstracts, Biosis, Zoological Records, Agris, Global Health, Food Science) as well as three databases through the Proquest, formerly Cambridge Scientific Abstracts (CSA), interface (Agricola, Biological Sciences, Toxline) and was performed from 12 June to 13 July 2011. The search for citations of studies conducted in human populations or in vitro included general and specific terms for bacteria (e.g. Enterobacteriaceae or Enterococcus or Escherichia coli), general antimicrobial susceptibility terms, terms related to changing antimicrobial susceptibilities (e.g. affect or effect or reduce or decrease), and factors or interventions related to particular actions (e.g. infection control) or pharmacology (e.g. dose-response relationship, pharmacodynamics) (Supplementary Appendix 2). Medline and CAB Abstracts were searched from 13 October to 31 December 2011. All searches included all available years of the databases, all geographical locations and were limited to those published in English. All citations were exported and de-duplicated (electronically and manually) in a web-based bibliographical database manager (RefWorks 2.0; http://www.refworks.com/).

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow chart documenting the literature retrieval* and inclusion/exclusion criteria for citations to identify modifiable non-antimicrobial factors or interventions to reduce the occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in cattle production systems. (* N SA, Search designed to return citations studying animal populations. N SH, Search designed to return citations studying human or in vitro populations. N H, Citations studying human-only populations. N IV, Citations studying entirely in vitro populations. N A, Citations studying animal populations.)

Relevance screening of abstracts and full-text citation

Each abstract (or title only, where no abstract was available) was screened using the question: ‘Does this citation describe modifiable non-antimicrobial interventions that may change antimicrobial resistance, or else modifiable factors that may be associated with antimicrobial resistance’? Citations reporting modifiable factors or interventions were retained, and citations reporting only non-modifiable factors such as breed, sex, or geographical location were excluded. Full text citations were screened with the same question as the abstracts. All screening of abstracts and review of full text citation was performed independently by two reviewers. The review team included three veterinary epidemiologists with expertise in the subject matter, a veterinary pharmacologist and a research assistant. Citations were included in the review or excluded with complete agreement by the two reviewers. In the case of disagreement, the citation was included or excluded on the basis of a review by a third member of the team.

Data extraction from citations of studies investigating non-antimicrobial use interventions or factors

Data on the following were extracted from full-text citations of studies conducted in animal populations (including studies also involving a human population): animal species, study design, reported modifiable non-antimicrobial risk factors and interventions, referent or control group, bacteria or bacterial genes isolated, antimicrobial susceptibility or antimicrobial resistance genes, the association(s) between antimicrobial susceptibility and non-modifiable risk factors (i.e. significant, non-significant), and the direction of the associations. Multiple drug resistance was extracted from those studies where multiple drug resistance was defined and investigated, and from studies where susceptibility to two or more antimicrobials in combination was reported (excluding the combinations of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and quinpristin-dalfopristin).

For exclusively human or in vitro studies, extracted data were limited to study population, study design, modifiable factor or intervention, and the direction of the associations. We placed this limitation because data from studies conducted in animal populations were assumed to be of greater relevance to our objective, and the much larger volume of citations in human populations exceeded our capacity for full data extraction. Thus, resources were mainly allocated to detailed data extraction from animal population studies and their qualitative review (see below).

For all studies, specific modifiable non-antimicrobial factors and interventions were aggregated into categories. The categories were not established a priori, but were developed iteratively by two independent reviewers. Separate categories were developed for studies in animal, human and in vitro populations, and the categories were then reviewed and evaluated qualitatively for common themes.

Quality assessment of animal-population studies

An assessment was made of the quality of studies in animal populations only. Any studies reporting only descriptive or raw data were excluded from the assessment. The purpose of the assessment was to identify and remove from the review any studies with methodological flaws or biases that would adversely affect the validity of the scoping review. This quality assessment instrument was a pretested questionnaire that was adapted from the GRADE assessment and risk-of-bias approach [Reference Guyatt21] (Supplementary Appendix 3). Two reviewers independently evaluated the stated inclusion/exclusion criteria for observational studies, or group allocation for randomized or experimental studies, assessed the impact of randomization (or lack of randomization) where appropriate, evaluated appropriateness of the statistical analysis, reviewed whether other procedures were defined, appropriate and used correctly, and determined if biases or uncontrolled confounders may have influenced the validity of the results. Studies were ranked either as high, moderate, or low quality, or else unreliable. In cases of disagreement, a third person reviewed the study, which was then classified on the basis of the third review. Only those studies ranked as being of high or moderate quality were retained.

RESULTS

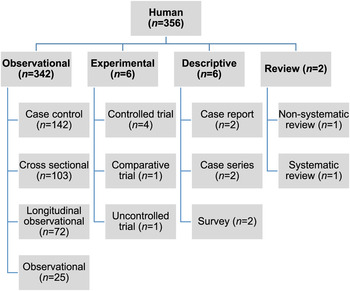

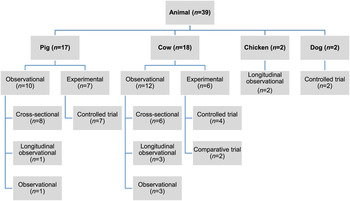

Of the 27 060 de-duplicated citations, 506 reported on modifiable non-antimicrobial factors or interventions. Most of these described studies in human populations exclusively (n = 356, 70%), 16% (n = 82) involved animal populations, and 13% (n = 68) were conducted entirely in vitro (Fig. 1). Of the retained citations involving human and animal populations, the most common study type was observational (n = 366, 93%) (Figs 2 and 3).

Fig. 2. Numbers of citations by study type reporting statistically significant results between non-antimicrobial factors and antimicrobial resistance in human populations.

Fig. 3. Distribution of study design from retained citations studying non-antimicrobial factors associated with antimicrobial resistance in animal populations.

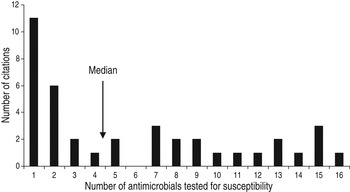

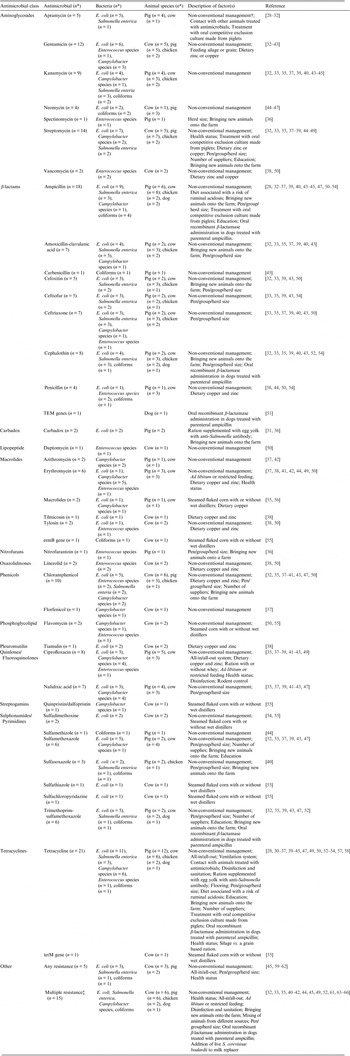

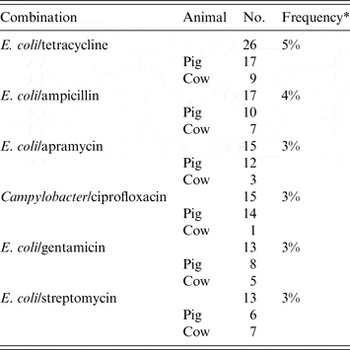

The animal populations studied in the retained studies after the qualitative assessment (n = 39) were cattle (n = 18), pigs (n = 17), chickens (n = 2) and dogs (n = 2). There were five bacterial genera, species or types investigated individually or in combination: E. coli (n = 21, 54%), Salmonella enterica (n = 8, 20%), Campylobacter species (n = 7, 18%), coliforms (n = 5, 13%), and Enterococcus species (n = 3, 8%). Two studies investigated antimicrobial resistance genes. Most studies examined only one bacterial genus or species (n = 31, 79%), 15% (n = 6) studied two and 5% (n = 2) studied three. Overall, antimicrobial susceptibility to 40 different antimicrobials from 14 antimicrobial classes was reported (Table 1), and the median number of antimicrobials included in a study was three (range 1–16) (Fig. 4). There were 485 associations between specific modifiable factors or interventions and antimicrobial susceptibility (or genes in a specific bacterial species) reported, and specific bacteria/antimicrobial susceptibility combinations (e.g. E. coli and tetracycline) occurred at a frequency of ⩽5%. The most frequent combinations were E. coli and tetracycline, ampicillin, apramycin, gentamicin, or streptomycin, and Campylobacter species and ciprofloxacin (Table 2).

Fig. 4. Number of antimicrobials* tested for susceptibility in in animal population citations reporting associations between non-antimicrobial factors or interventions and antimicrobial resistance. [* Including ‘any resistance’ (as defined by the authors) or multiple drug resistance (as defined by the authors) or any two or more antimicrobial combinations reported (excluding trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and quinpristin-dalfopristin).]

Table 1. Descriptions of non-antimicrobial factors, tested antimicrobials, bacteria and, animal species in animal population citations (n = 39) that investigated associations between antimicrobial resistance and non-antimicrobial factors

* Number of citations.

† The following management systems as defined in the studies were aggregated under non-conventional management systems: organic, antimicrobial-free, extensive (e.g. pasture raised pigs), natural production, animal friendly or ecological.

‡ Multiple drug resistance was captured from studies where multiple drug resistance was defined and investigated, as well as any study where susceptibility two or more antimicrobials in combination were reported (excluding trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and quinpristin-dalfopristin).

Table 2. The most frequently* identified bacteria/antimicrobial/species combinations reported from retained citations (n = 39) in animal populations that investigated the associations between modifiable non-antimicrobial factors or interventions and antimicrobial resistance.

* Denominator was total number of associations reported in ‘reliable’ studies (n = 485). All other bacteria/antimicrobial combinations were identified at a frequency of < 2%.

Specific associations between a given factor or intervention with antimicrobial resistance in a given animal population (e.g. the association between non-conventional management and tetracycline susceptibility in E. coli from cattle) were reported in only a small number (range 1–3) of studies. The majority (n = 303, 62%) of specific associations were reported in only one study, 24% (n = 115) were reported in two studies, and 14% (n = 67) were reported in three studies.

Most reported associations between antimicrobial susceptibility and a modifiable non-antimicrobial factor or intervention were not statistically significant (60%, n = 290), 27% (n = 132) (27%) of the associations were interpreted as significant [P⩽0·05 and confidence interval (where reported) that excluded 1] and the remainder of the associations that were reported (n = 63, 13%) were descriptive in nature or else raw data (Table 3). Use of a non-conventional management systems (e.g. organic, antimicrobial-free, extensive systems), increasing herd, group or pen size and all-in/all-out systems were the factors with the greatest number of reported associations (n = 183, 68 and 52, respectively). For the factors of non-conventional management systems and increasing herd, group or pen, most associations were non-significant (64% and 90%, respectively); however, the majority (83%) of the associations for all-in/all-out systems were significantly associated with a decrease in antimicrobial resistance.

Table 3. Direction of effect of associations between modifiable non-antimicrobial factors or interventions and antimicrobial resistance in retained citations (n = 39) in animal populations

NRC, National Research Council Canada.

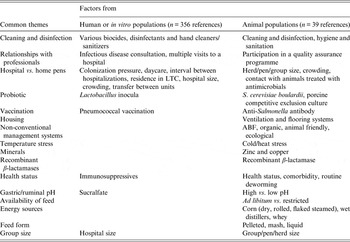

In the retained studies from human and in vitro populations (n = 424) (Table 4), most factors were associated with an increase, rather than decrease in antimicrobial resistance. The most frequently reported factor (n = 289, 68%) was the duration of hospitalization (or time spent in the intensive care unit or in another ward).

Table 4. Distribution of categories of modifiable non-antimicrobial factors or inventions described retained citations in human populations (n = 356) where there was a statistically significant association with antimicrobial resistance

Considering combined data from human, animal and in vitro populations, 16 common themes were observed (Table 5). These themes reflected aspects on the use of compounds (e.g. vaccinations, probiotics, and recombinant b-lactamases), infection control (e.g. cleaning and disinfection, hospital vs. home pens), health (comorbidity, stressors, immunosuppression), education and relationships with professionals (infection disease consultations, participation in quality assurance programmes) and others. Studies in animal populations were represented in all themes despite fewer studies retained (n = 39) compared to retained studies in human populations (n = 356) or entirely in vitro studies (n = 68). Studies performed in human populations or entirely in vitro belonged to only 50% (n = 8) of the themes and belonged to themes identified in animal populations.

Table 5. Common themes of modifiable non-antimicrobial factors or interventions reported in citations from retained animal, human or in vitro populations

LTC, Long-term care; ABF, antibiotic free.

DISCUSSION

Using scoping review methodology, we identified the evidence supporting use of non-antimicrobial factors or interventions for reduction of antimicrobial resistance with particular emphasis on animal populations. We also assessed the quantity and quality of this evidence, as well as the distribution of antimicrobials selected for susceptibility testing in enteric bacteria, the distribution of enteric bacteria investigated and the populations studied (animal, human, in vitro) in a transparent, reproducible manner.

An important finding of this review was the wide breadth of data on non-antimicrobial factors associated with antimicrobial resistance; however, the depth of research supporting effect measures for these factors was limited, particularly concerning any specific factor for any particular antimicrobial/bacterial combination in any particular animal population. The limited depth of applicable research in animal populations is perhaps somewhat offset by similar research in human populations, from which some analogies may be drawn.

Another key finding of this review was that most of the non-antimicrobial factors or interventions tested in animal populations were not significantly associated with antimicrobial resistance. Additionally, where significant associations were reported, they were not generally in a single direction (either associated with an increase or decrease in the occurrence of antimicrobial resistance, or both). In light of the general paucity of research in this area, we did not identify any modifiable non-antimicrobial factors or interventions that could on the basis of available evidence be strongly recommended for consideration, application or adoption by the North American cattle industry without additional research, or unless the factor(s) or intervention(s) have other well established positive industry impacts and would likely not propagate antimicrobial resistance.

When considering together the results of studies in animal and human populations, some non-antimicrobial factors (e.g. health management, improving sanitation) may be sufficiently well-established principles for disease prevention that they may not need additional research; that is, before veterinarians and beef producers could be convinced of the value in adoption by the North American cattle industry. Some of these factors (e.g. diet, reducing pen size, heat/cold stressors, limiting contact with animals treated with antimicrobials, reducing time in a hospital pen) may also result in other positive outcomes (i.e. improved animal health and welfare, public health, food safety) in addition to reducing antimicrobial resistance. To the extent that implementation of such disease prevention strategies reduces the need for antimicrobial treatment, benefits in reduced resistance selection pressure could indirectly arise. However, adoption by sectors of the cattle industry may be technically or practically more difficult and require additional resources, changes to facility design, management style, or systems. Regardless, additional research is needed to adequately demonstrate the efficacy of any of these factors to reduce the occurrence of antimicrobial resistance, either as a whole or in specific ‘bug/drug’ combinations, in public health or animal health settings.

One specific intervention that has been studied in human populations, but not to our knowledge in cattle populations, is the use of vaccination to address resistance concerns in bacterial populations. There is good evidence that pneumococcal vaccination reduces antimicrobial resistance in pneumococcal bacteria in humans. This finding has been attributed to a reduced incidence of disease and a shift to less phenotypically resistant pneumococcal strains. In cattle studies, vaccination for bovine respiratory disease complex or undifferentiated fever was associated with reduced frequency of respiratory disease and systemic antimicrobial treatment [Reference Makoschey22, Reference Booker23]; however, effects on antimicrobial susceptibility were not reported. It would be helpful if future studies of vaccine efficacy in food animals included evaluation of effect on antimicrobial resistance in both the pathogen of interest and commensal bacteria in target (e.g. lung) and non-target sites, such as the gastrointestinal tract.

Several knowledge gaps were identified concerning non-antimicrobial interventions against resistance. For example, no studies were found on the impact on resistance of some common North American cattle industry practices such as preconditioning (as a whole) or factors associated with preconditioning (e.g. vaccination, reducing stressors associated with weaning, transportation, feed introduction), the impact of different bedding packs and materials, the use of hospital or sick pens vs. ‘treat and go-home’ practices, impact of veterinary consultations, and other educational actions directed at producers. Factors such as mixing groups of treated and untreated animals, open vs. closed population management, and all-in/all-out systems that have been studied in other animal species (e.g. pigs) need to be assessed for relevance to the various cattle production sectors. Associations between biosecurity measures in cattle production and antimicrobial resistance are also areas worthy of additional research, based on the findings in human populations related to time spent in the hospital or intensive care wards.

Although the findings of this review may be limited by the decision to not update from 2011 the searches during the review process, it has been reported that updates to Cochrane Reviews altered conclusions in only 9% of updated reviews [Reference French24, Reference Young25]. Our review included comprehensive searches (multiple databases and all years searched) and, a large number of citations screened (27 060). To our knowledge, similar reviews have not been published. The findings provide a baseline for evidence-based recommendations on interventions to reduce the occurrence of antimicrobial resistance, identify areas for future research including knowledge gaps and establish a framework upon which data from more recent and future studies can be added.

The findings may also have been limited by the decision to include only English language publications, but the impact of this is difficult to determine [Reference Moher26, Reference Juni27]; other agri-food reviews have reported that the number of relevant non-English-language citations were few and therefore unlikely to impact findings [Reference Young25]. As many of the countries with influential research on antimicrobial resistance publish in English-language peer-reviewed journals or provide other documents in English, this potential bias was likely small.

CONCLUSION

A diverse but shallow body of evidence presents investigated factors or interventions associated with antimicrobial resistance and the addition of human studies strengthened the data reported in animal populations. However, the results of this review could not identify any modifiable non-antimicrobial factors or interventions that could be recommended for consideration, application or adoption by the North American cattle industry without additional research. Research is needed to more comprehensively study these interventions on the occurrence of antimicrobial resistance as a whole and in specific ‘bug/drug’ combinations of public and animal health interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0950268815000722.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the guidance, assistance, advice and input from Paul Morley from Colorado State University and Lisa Waddell from the Public Health Agency of Canada.

This research was supported by the National Integrated Food Safety Initiative of the United States Department of Agriculture (Grant 2010-51110-21083).

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.