INTRODUCTION

Measles is a highly contagious acute viral disease characterized by fever, cough, conjunctivitis and a generalized maculopapular rash [Reference Griffin and Knipe1, Reference Rima and Duprex2]. The disease is caused by the measles virus, a member of the genus Morbillivirus within the family Paramyxoviridae.

An efficient vaccine conferring long-lasting protection against measles has been available since the 1960s [3]. Measles was a typical childhood disease in the pre-vaccination era, but at present measles also affects non-immunized adolescents and adults, and international travellers [Reference Kondova4–Reference Pervanidou7].

Measles immunization with monovalent vaccine started in Serbia in 1971. The bivalent measles/mumps immunization programme was introduced in 1981. Since 1994, the trivalent measles/mumps/rubella (MMR) vaccine is given at age 12–15 months with a second dose at 7 years. Regular reviews of the immunization records are conducted throughout the year and if a child has missed the second dose, revaccination should be done before the age of 15 years [8]. During recent years MMR coverage rates in Serbia were above 95% [9], but recent results from a UNICEF survey showed that only 53% of children aged between 24 and 35 months from Roma settlements had received the vaccine [10].

Between 2002 and 2004 the Institute of Public Health (IPH) of Serbia initiated a supplementary immunization programme specifically targeting Roma communities in 17 districts. During this campaign 36 611 Roma children aged 0–14 years were registered and included in the Serbian healthcare system. The programme was initially designed to reach 23 339 Roma children. However, only 12 090 children actually received the MMR vaccine since some refused immunization or had changed their place of residence. The proportion of Roma children having received two doses of measles-containing vaccine increased from 36·3% before the campaign to 69·3% after. Supplementary immunization activities against measles have been conducted annually for the general population during ‘European Immunization Week’ since 2006. For instance, in 2011 a supplementary immunization activity was conducted in 27 municipalities where the first-dose routine MMR coverage was <95% [11].

After the introduction of measles immunization in Serbia in 1971, measles outbreaks were initially recorded every 3–5 years. The outbreak in 1997 with 4000 cases was the last large outbreak in the country. A smaller outbreak with 191 cases was recorded in Vojvodina in 2007 [Reference Nedeljković12]. Between 2008 and the end of 2010 only a few sporadic measles cases were reported in Serbia. This paper analyses the epidemiological and virological surveillance data of a measles outbreak with 363 registered cases between December 2010 and August 2011.

METHODS

Ethics statement

The investigation of this outbreak was done within the framework of non-research national public health surveillance for measles and did not comprise any previously planned activities that could have been reviewed by an ethics committee or institutional review board. Sample collection was done for laboratory diagnosis as part of standard patient care and did therefore not require written informed consent.

Case definitions

A laboratory-confirmed measles case was defined as a person with generalized, maculopapular rash lasting >3 days, temperature ⩾38·3 °C, cough, coryza or conjunctivitis (= clinical case definition), who has measles-specific IgM antibodies in the blood and/or measles virus RNA in nose/throat swabs. An epidemiologically linked case is an individual that meets the clinical case definition, has not been confirmed in the laboratory and is geographically and temporally linked (rash onset 7–21 days apart) to a laboratory-confirmed case or to another epidemiologically confirmed measles case in the same transmission chain [13]. According to Serbian legislation a single measles case may mark an outbreak in an elimination setting.

Data source

The epidemiological data analysed in this paper originate from the surveillance database of the IPH of Serbia ‘M. Jovanović-Batut’ in Belgrade.

Sample collection and laboratory testing

Clinical samples were collected from the initial 5–10 reported cases per outbreak location. From 141 patients only serum was available, from six patients only nose/throat swabs and from 46 patients serum and nose/throat swabs were collected.

Sera were collected within 21 days, nose/throat swabs within 12 days after onset of rash. Laboratory investigation included the detection of measles-specific IgM antibodies using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Enzygnost®, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Products GmbH, Germany) and/or the detection of measles RNA in nose/throat swab samples by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers and probes kindly provided by the Statens Serum Institute, Denmark (MB f: 5′-GGCAAGAGATGGTAAGGAGGT-3′, MB r: 5′-CGGCAGTGATACCGAGTTC-3′, MB probe: 5′-FAM-TGGAAAGGTCAGTTCCACATTGGCAT-TAMRA-3′, Nielsen LP, Department of Microbiological Diagnostics and Virology, 2009, unpublished data).

Phylogenetic analysis

Nose/throat swabs of 36 PCR-positive patients were sent to the WHO European Regional Reference Laboratory in Luxembourg for sequencing and genotyping. Phylogenetic analysis was based on the Kimura two-parameter method and the Neighbour-Joining algorithm using the 450 nt at the carboxyl-terminal of the nucleoprotein gene. The sequences from Serbia shown in the phylogenetic tree are available under GenBank accession numbers FR850160 and KM281809–15.

RESULTS

Outbreak description

On 31 December 2010 the IPH Leskovac reported a measles outbreak in the Roma settlement at Brestovac, a municipality of Leskovac in the district of Jablanica. Nine cases were initially laboratory confirmed. The presumed index case had returned from a prolonged stay in Duisburg (Germany) on 28 November and developed measles on 6 December 2010. The infection was laboratory confirmed by detection of measles-specific IgM antibodies. From December 2010 until January 2011 the infection spread within the Roma population throughout Leskovac. By the end of March 2011, three measles outbreaks were reported also affecting the general population in different parts of the city. The infection had been spread during contacts between the general population and infected Roma, for example during work. Overall, 279 cases were recorded in Leskovac and epidemiological investigations confirmed that all outbreaks were connected with each other.

In February 2011, a measles patient from Leskovac was hospitalized at the Children's Clinical Centre in Niš, causing a nosocomial outbreak in the Department of Internal Medicine. In total, 23 people were affected including 16 children aged ⩽9 years and seven healthcare workers aged >30 years. All people infected during this nosocomial outbreak were unvaccinated. The infection also spread to the general population of Niš increasing the total number of cases to 56.

Family clusters of measles cases linked to the ongoing outbreak were also detected in Belgrade in March 2011 and by April in Ruma in the North of Serbia, both in Roma communities and both after patients from Niš had travelled to visit their relatives. A single epidemiologically unrelated case was reported from Valjevo in the Western part of the country in May 2011. The affected person was a bus driver who had travelled to Prague, Slovenia and Italy at the time of infection, but did not recall any contact with a rash/fever case. In Zaječar district in the Eastern part of the country close to the border with Bulgaria seven cases were serologically confirmed in July 2011. The source of infection was unknown and these cases could not be epidemiologically linked to any other cases. No samples for genotyping and molecular epidemiology and no further data were available from these patients.

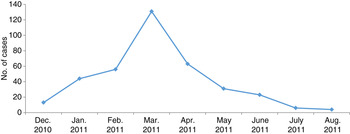

Overall 371 measles cases were reported from throughout Serbia between December 2010 and August 2011, of which 363 cases were epidemiologically linked to the same transmission chain and are further analysed below. The overall disease incidence during the outbreak period was 4·93 cases/100 000 population, with a peak in March 2011 (Fig. 1). A total of 130 (35·8%) of the 363 patients were hospitalized, 15 (4·1%) with pneumonia, but there were no fatalities. Although information about ethnicity was not recorded, based on the place of residence (in locations with or without Roma settlements) an estimated minimum of 75% of the cases were from Roma communities.

Fig. 1. Number of measles cases per months reported in Serbia between December 2010 and August 2011.

In reaction to the outbreak, the vaccination records of all children aged between 1 and 14 years were checked and unvaccinated as well as incompletely immunized children were vaccinated. The public health authorities disseminated information about the measles outbreak and infected persons were isolated as much as possible. Additionally, people who had been in contact with measles patients were placed under medical surveillance and were immunized if necessary.

Age and sex distribution of the cases involved in the outbreak

Almost 38% of the 363 patients with clinical signs of measles were pre-school children aged ⩽4 years (19·3% were aged <1 year and 18·5% were aged 1–4 years) and 27·3% were aged ⩾30 years. The other age groups comprised 8·3% (5–9 years), 6·9% (10–14 years), 6·3% (15–19 years) and 13·4% (20–29 years) of all patients. Considerably more females than males (57·0% vs. 43·0%) were affected.

Vaccination status

According to the medical records of the patients, only five (1·4%) out of 363 patients were immunized with two doses of measles-containing vaccine (n = 3, 1 and 1 in the 5–9, 10–14 and 15–19 years age groups, respectively), while 18 (4·9%) had received only one dose of vaccine (n = 11, 5, 1 and 1 in the 1–4, 5–9, 10–14 and 15–19 years age groups, respectively). For 229 (63·1%) patients the vaccination status was unknown and 111 people (30·6%) were unvaccinated. Children aged <1 year had not yet received any measles vaccine. Of the 99 patients aged ⩾30 years, 68 (68·7%) had an unknown vaccination status and 31 (31·3%) were unvaccinated.

Laboratory confirmation

Of the 141 patients of whom only serum was collected, 77 were measles IgM positive and 55 were negative (Table 1). Equivocal test results were obtained for nine patients, but no convalescent sera were available for confirmation. Of the 46 patients with serum and nose/throat swab samples, 27 were positive for measles-specific IgM antibodies and RNA. For three patients the sera collected within 3 days after rash onset were equivocal in the ELISA, while the swabs were PCR positive. An additional two patients were positive for measles-specific RNA, while no IgM antibodies were detected in the serum collected within 2 days after rash onset. Four of the six patients with nose/throat swabs only were PCR positive (Table 1). Laboratory confirmation was obtained for 16 (72·7%) of the 22 patients aged <1 year and for 36 (72·0%) out of 50 patients aged >29 years.

Table 1. Laboratory investigation results

n.a., Not available.

Overall 113 (58·5%) of 193 patients tested or the entire 363 cases (31·1%) recorded were laboratory confirmed. The remaining 250 recorded cases (68·9%) were epidemiologically linked to laboratory-confirmed cases.

Age, gender and vaccination status of the laboratory-confirmed cases

The youngest laboratory-confirmed patient was aged 3 months and the oldest was 56 years. The age group distribution was similar to the overall cohort except for an underrepresentation of <1-year-olds since sample collection from these infants was difficult and permission was not obtained in all cases.

None of the 113 laboratory-confirmed cases had a record of measles vaccination; 28 (24·8%) patients were unvaccinated and for 85 (75·2%) the vaccination status was unknown. Similar to the overall cohort more females than males were affected (57·0% vs. 43·0%).

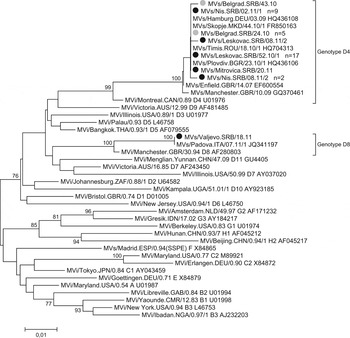

Phylogenetic analysis

From 31 of the 36 measles RNA-positive nose/throat swabs N450 sequences for genotyping were obtained. All of these sequences except for the one obtained from the patient from Valjevo belonged to genotype D4 (Fig. 2). Three different sequence variants were identified with most (n = 27) of the sequences belonging to D4-Hamburg. The two additional D4 variants detected in Niš and Leskovac differed by 1 nt each from the main variant. D4-Hamburg strains and another variant differing by 1 nt had already been detected earlier in 2010 in Belgrade (grey dots, Fig. 2). Interestingly a D8 strain was detected in the epidemiologically unrelated patient from Valjevo (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Phylogenetic tree showing measles viruses detected in Serbia between 2010 and 2011. The phylogenetic tree is based on the Neighbour-Joining and Kimura two-parameter methods using 450 nt of the measles virus N gene. Measles strains detected in Serbia before the outbreak are marked with grey dots, strains found during the outbreak period with black dots. The numbers behind the strains show how often this sequence was found in that location. Only bootstrap values of ⩾70 are shown.

DISCUSSION

The present study describes a measles outbreak in Serbia that lasted from December 2010 to August 2011 and involved 363 cases. During the same time period, an additional eight unrelated cases were identified. Measles infection was confirmed serologically and/or by PCR in 113 of 193 patients with specimens. Most sera were collected within 2–4 days after rash onset, which could explain a number of the IgM-negative results. It was not possible to obtain convalescent sera for additional testing from the mostly affected Roma population. In addition, all PCR-positive nose/throat swabs were obtained within 5 days after rash onset corresponding to the time of highest viral load (within 3 days after rash onset [14]). Besides a late collection time point, inadequate sample collection or transportation may have contributed to negative PCR results. Thus, the overall low laboratory confirmation rate might have been caused by the sample collection time points, sample quality and the lack of a second serum for IgM-negative patients.

A total of 130 (35·8%) out of 363 cases were hospitalized. The hospitalization was in most cases a preventive measure since the health authorities were concerned that patients with inappropriate home care conditions were at increased risk of disease complications. In all cases hospitalization was done with the consent of the children's parents or guardians. The most frequent complication in hospitalized patients was pneumonia (4·1% of the reported outbreak cases). More females than males were affected, especially children and adolescents, but the reasons for this are unclear.

Phylogenetic analysis revealed that all cases linked to the outbreak belonged to the measles D4-Hamburg lineage which has been detected in many European countries during the previous years. This strain was introduced from the UK to Germany at the end of 2008. By 2011 it had spread to many European countries, including Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) causing more than 25 000 cases. The spread of this strain was often linked to movements of Roma throughout Europe [Reference Mankertz15]. The D4-Hamburg strain had already been detected in Serbia at the beginning of 2010 in the Roma population of Belgrade (five cases). The same measles variant had also caused an outbreak in neighbouring FYROM, starting in the second half of 2010. The source of infection was unknown for these initial cases from Belgrade and the infection did not spread to the general population. Except for a case in an unvaccinated child in week 43 (Fig. 2), there were no other measles cases in Serbia until end of December 2010. The presumed index case of the 2010/2011 outbreak in Serbia came from Germany for the Christmas and New Year holidays and was classified as imported according to epidemiology and the WHO case definition. After its introduction from Germany, the infection spread mostly in the unvaccinated population in Serbia. Although the exact numbers are unknown, Roma communities were mostly affected, which is similar to outbreak observations from other countries [Reference Pervanidou7, Reference Hegasy16].

Measles virus genotype D8 was identified in the epidemiologically unrelated case from Valjevo, who had travelled to different countries during the incubation period including Italy where identical D8 strains were reported in 2011 [Reference Filia17].

Children aged ⩽4 years and adults aged between 30 and 40 years were most affected.

A similar age distribution has been reported from outbreaks in other countries, such as France and Romania [Reference Huoi18, Reference Stanescu19]. In France, a high measles incidence was observed in children aged <1 year, probably because they were not yet vaccinated and no longer protected by maternal antibodies [Reference Huoi18]. This is also the most likely explanation for the 19·3% of cases aged <1 year reported during the Serbian outbreak. While no information is available about the measles IgG antibody status of the mothers, none of these children had received measles vaccination and due to difficulties with sample collection and lacking parental consent, only a few samples were available for laboratory confirmation. In Romania, where the highest numbers of cases were registered in 1- to 4-year-old unvaccinated children, parental concerns about the benefits of vaccination were identified as an explanation for the accumulation of susceptibles [Reference Stanescu19]. According to our data, 93·7% of the measles cases were not vaccinated or had no information about their vaccination status and therefore were most likely to be unvaccinated. A significant immunity gap was observed in adults aged ⩾30 years probably because they were never vaccinated (about one third were not vaccinated, the remaining two thirds had unknown vaccination status) or had lost protective antibodies after the single-dose vaccination offered during their childhood.

The high number of adults with unknown vaccination status may at least in part be explained by the fact that a large number of refugees from other former Yugoslav Republics settled in Serbia in the mid-1990s and it was difficult to monitor their migration and immunization status. Thus, several cohorts of susceptibles with very low vaccine coverage emerged with an increasing risk for large outbreaks [Reference Batzing-Feigenbaum20, Reference Roggendorf21]. On the other hand, the relatively low incidence in the 5–19 years age group is likely due to the vaccination campaign between 2002 and 2004.

To prevent disease spread and eventually stop the outbreak, measles cases were isolated and unvaccinated contacts were immunized according to national regulations. In addition, the previously mentioned annual supplementary immunization activities were performed, which in 2011 included 27 municipalities. The last confirmed case related to this outbreak was notified in August 2011 and only two laboratory-confirmed cases were reported in 2012/2013, both of them classified as imported. No further cases were detected until end of 2014, when a resurgence of measles was observed in the country.

CONCLUSIONS

The present report provides a thorough retrospective analysis of the measles outbreak in Serbia from 2010 to 2011. The epidemic comprising 363 cases occurred after several years of very low disease incidence and despite a high routine immunization coverage in Serbia. This suggests that special efforts to identify and vaccinate susceptible population groups are required even in countries with apparently good disease control.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to the laboratory staff at the Institute Torlak and at the Institute of the Medical Faculty in Niš for their technical assistance and to the epidemiologists and health workers at the Serbian public health centres involved in measles surveillance. The authors also express gratitude to Dr Nielsen, Statens Serum Institute, Denmark (Department of Microbiological Diagnostics and Virology) for providing sequences of MB primers and the probe. Many thanks to Professor Bata Tiodorović from the Medical Faculty in Niš for very useful comments. The authors also thank Emilie Charpentier from the Department of Infection and Immunity of the Luxembourg Institute of Health for her excellent technical assistance.

The authors are grateful to the Serbian Ministry of Health for financially supporting measles surveillance and the laboratory investigations performed during the outbreak. They also thank the Luxembourg Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financially supporting the work done in Luxembourg.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.