Introduction

Tropical forests house exceptional biodiversity and play a disproportionate role in global ecosystem services, including climate and precipitation regulation (Staal et al. Reference Staal, Tuinenburg, Bosmans, Holmgren, Van Nes and Scheffer2018). However, these ecosystems face significant threats due to climatic and local anthropogenic disturbances (Moura et al. Reference Moura, Noriega, Cerboncini, Vaz-de-Mello and Klemann-Jr2021, López-Bedoya et al. Reference López-Bedoya, Bohada-Murillo, Ángel-Vallejo, Audino, Davis and Gurr2022, Lapola et al. Reference Lapola, Pinho, Barlow, Aragão, Berenguer and Carmenta2023). With the strong global demand for timber and the widespread nature of timber-harvesting operations, logging is one of the main drivers of tropical forest degradation (Putz et al. Reference Putz, Zuidema, Synnott, Peña-Claros, Pinard and Sheil2012).

The impacts of selective logging on tropical biodiversity are commonly assessed using taxonomic diversity metrics (e.g., species richness and composition) and ecological processes (Slade et al. Reference Slade, Mann and Lewis2011, Burivalova et al. Reference Burivalova, Şekercioğlu and Koh2014). However, selective logging can also affect functional diversity by favouring species with some specific traits (Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Edwards, Larsen, Hsu, Benedick and Chung2014b, Ding et al. Reference Ding, Zang, Lu and Huang2019) – for example, specialists in canopy gaps and vine tangles (Schnitzer et al. Reference Schnitzer, Michel, Powers and Robinson2020). Studies have also shown that integrating functional traits can complement taxonomic diversity metrics (Cerullo et al. Reference Cerullo, França, Finch, Erm, Griffiths and Louzada2023), providing valuable insights into the resilience of species and ecosystems to environmental degradation (Mouillot et al. Reference Mouillot, Graham, Villéger, Mason and Bellwood2013). Moreover, functional diversity tends to better predict biodiversity–ecosystem functioning relationships than taxonomic diversity metrics (Tilman Reference Tilman2001, Gagic et al. Reference Gagic, Bartomeus, Jonsson, Taylor, Winqvist and Fischer2015).

Despite the increasing use of functional diversity metrics to investigate the impacts of land-use change on tropical biodiversity, there remains limited understanding of how selective logging affects faunal functional diversity. For example, only three out of 35 such publications have assessed the influence of logging on fauna functional diversity within Tropical America forests (see Table S1 in Appendix S1 for details). Moreover, most empirical studies in tropical logged forests are focused on single taxa (e.g., Hamer et al. Reference Hamer, Newton, Edwards, Benedick, Bottrell and Edwards2015, Cerullo et al. Reference Cerullo, Edwards, Mills and Edwards2019; but see Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Woodcock, Edwards, Larsen, Hsu and Benedick2012, Bicknell et al. Reference Bicknell, Struebig and Davies2015) and/or have compared functional diversity metrics between selectively logged and undisturbed forests without accounting for differences in harvesting intensities (e.g., Baraloto et al. Reference Baraloto, Hardy, Paine, Dexter, Cruaud and Dunning2012a, Ewers et al. Reference Ewers, Boyle, Gleave, Plowman, Benedick and Bernard2015). However, selective logging is not a uniform disturbance, and mean effect sizes and the mechanisms driving biodiversity responses to logging may vary among taxonomic groups (Burivalova et al. Reference Burivalova, Şekercioğlu and Koh2014) and with time since logging (Ernst et al. Reference Ernst, Linsenmair and Rödel2006, Kpan et al. Reference Kpan, Ernst and Rödel2021). Consequently, we need empirical evidence on how logging intensification and time since logging influence multiple metrics of faunal functional integrity to better understand post-logging biodiversity recovery and inform effective management and conservation strategies for tropical forests.

Here, we assess the influence of selective logging intensification and time since harvesting operations on the taxonomic and functional diversity of birds and dung beetles (Coleoptera: Scarabaeinae) in the Brazilian Amazon. We focus on birds and dung beetles as our focal taxa due to their cost-effectiveness as bioindicators (Gardner et al. Reference Gardner, Barlow, Araujo, Ávila-Pires, Bonaldo and Costa2008) and contributions to key ecological processes such as seed dispersal and nutrient cycling (Nichols et al. Reference Nichols, Spector, Louzada, Larsen, Amezquita and Favila2008, Godínez-Alvarez et al. Reference Godínez-Alvarez, Ríos-Casanova and Peco2020). Our dataset includes 7892 dung beetles and 5081 bird records from 45 and 182 species, respectively, surveyed within 48 logging management units distributed along a logging intensification gradient. We draw on this unique dataset to investigate the ecological impacts of selective logging on tropical forest fauna, asking three questions. First, how do bird and dung beetle functional and taxonomic diversity respond to logging intensification and time since disturbance? Here, we predict that logging intensification will result in lower bird and dung beetle functional and taxonomic diversity (Burivalova et al. Reference Burivalova, Şekercioğlu and Koh2014), which will be lower in recently logged forests (Fig. 1a; Kpan et al. Reference Kpan, Ernst and Rödel2021). Second, are beetle and bird responses to logging and time since disturbance driven by the loss of individuals across all species or by a non-random replacement of individuals among species? We expect logging to act as an environmental filter selecting for more functionally similar species (Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Tobias, Sheil, Meijaard and Laurance2014a), which will drive higher compositional dissimilarity through losses in abundances of forest-specialist species (i.e., abundance gradients) without significant abundance replacement (i.e., balanced variation in abundance; Fig. 1b). Thirdly, how do changes in disturbance-sensitive species influence biodiversity responses to logging and time since logging? We expect that taxonomic and functional diversity changes will be driven by the loss of rare and more disturbance-sensitive species (Fig. 1c; Leitão et al. Reference Leitão, Zuanon, Villéger, Williams, Baraloto and Fortunel2016).

Figure 1. Expected influence of logging intensification and time since logging on Amazonian fauna (a) taxonomic and functional diversity metrics, (b) abundance-based dissimilarity components and (c) community-weighted rarity index. Taxonomic metrics include species richness (i.e., total number of species per sampling site), abundance (i.e., total number of individuals per sampling site) and community-weighted biomass (i.e., average biomass of each species weighted by their abundance in each sampling site), whereas functional metrics include diversity (FDq; i.e., functional dissimilarity between species in a community), specialization (FSp; i.e., level of specialism in a community based on generalist/specialist species distribution across the functional space) and originality (FOr; i.e., level of functional redundancy between species in a community); see the ‘Methods’ section for further details. Abundance-based Bray–Curtis dissimilarity components include abundance gradients (i.e., individual loss of all species from one site to another) and balanced variation in abundance (i.e., individuals’ turnover between species losing and gaining individuals between sites). The community-weighted rarity index is based on species’ abundance, geographical range (distribution in a given space) and habitat breadth (occurrence across different habitats); further details are provided in the ‘Methods’ section.

Methods

Study region

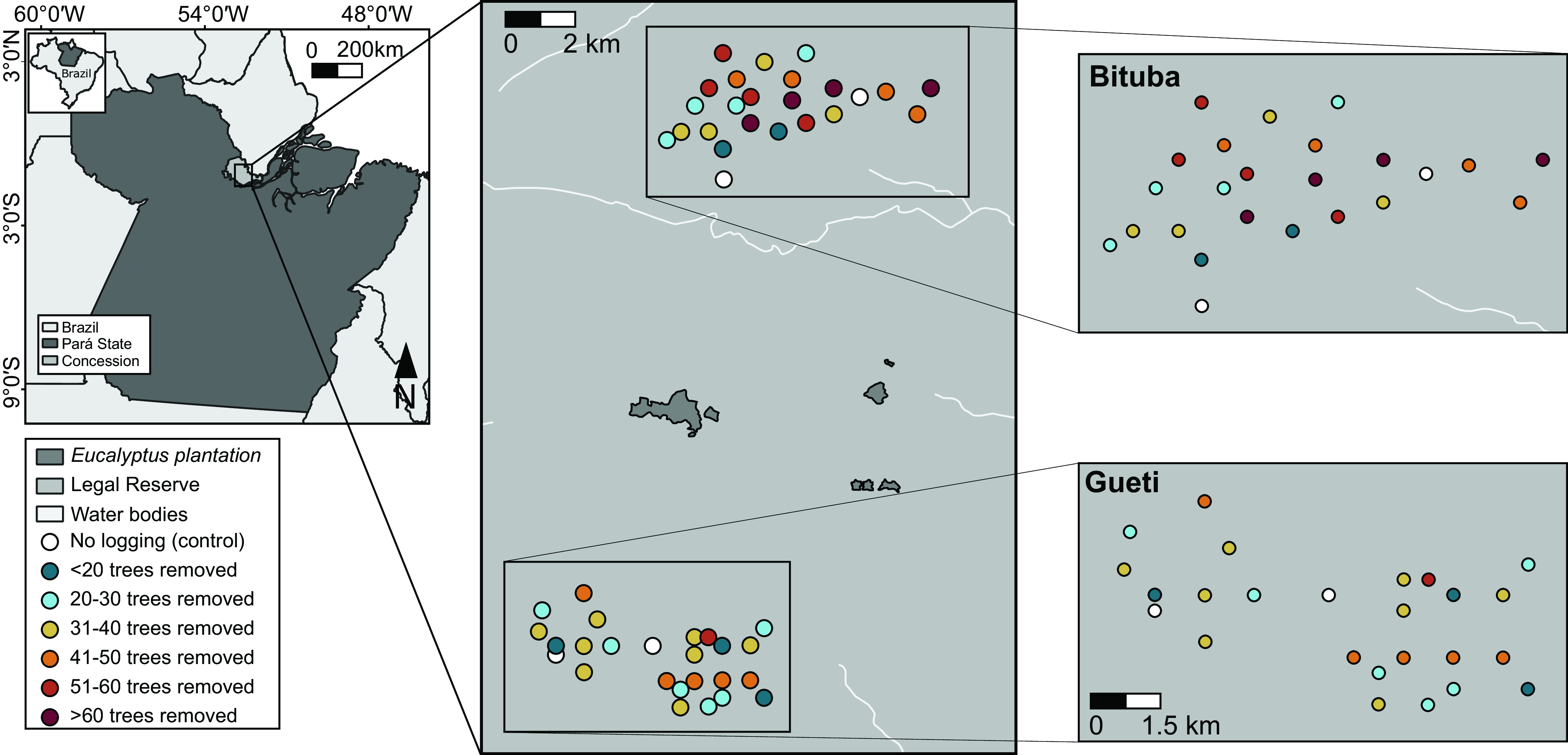

Our study focuses on the 1.7 Mha Jari Florestal forest concession in the north-eastern Brazilian Amazonia (00°27′–01°30′S, 51°40′–53°20′W; Fig. 2). The region experiences a tropical monsoon climate (Amw, Köppen) and has an average altitude of 203 m, annual temperature of 26.6°C and annual rainfall of 2357 mm. The logging concession covers c. 544 000 ha of native forest and follows reduced-impact logging (RIL) practices on a 30-year rotation. The native forests are often dominated by Dinizia excelsa Ducke (Fabaceae, Mimosoideae), which represents c. 50% of timber species harvested in some Amazonian regions (Barbosa Reference Barbosa1990). Logging operations are conducted within 10-ha logging management units (250 × 400 m) and involve mapping, measuring and identifying commercially viable trees with a diameter at breast height of ≥45 cm. Logging intensities (i.e., the number of removed trees; França et al. Reference França, Louzada, Korasaki, Griffiths, Silveira and Barlow2016) vary across logging management unities, and RIL practices include directional felling to minimize damage to other trees and cutting lianas on large trees during the inventory stage (Putz et al. Reference Putz, Zuidema, Synnott, Peña-Claros, Pinard and Sheil2012).

Figure 2. The location of our 10-ha sample sites (circles) within the Jari landholding. Bituba and Gueti regions were selectively logged in 2006 and 2009, c. 1.5–2.0 and 5.0–6.0 years before faunal surveys, respectively.

Experimental design

We followed the operational plan provided by the logging concession to select 48 management units (hereafter ‘sampling sites’) distributed across two regions of the concession: Bituba (selectively logged in 2006) and Gueti (selectively logged in 2009), which are ≥10 km apart, while distances among sampled sites ranged from 0.25 to 19.00 km (average 9.70 ± 7.00; mean ± SD) within each region. To assess logging impacts on a continuum, we chose sampling sites along a gradient of increased logging intensity, ranging from 0 (two unlogged control sites per region; Fig. 2) to 76 removed trees during harvesting operations (31.9 ± 20.5 across both regions) – which is within the average harvesting intensities in both study regions (Bituba: 32.60 ± 16.55 and Gueti: 23.20 ± 14.30 removed trees).

Fauna surveys

Fieldwork took place between January and March 2010 for dung beetles and between July and September 2011 for birds, c. 1.5–2.0 and 5.0–6.0 years after logging operations in the Gueti and Bituba regions, respectively. We conducted bird and beetle surveys in the 48 sampling sites, including 44 logged and 4 unlogged sites. We included three additional control areas for dung beetles in the same study concession, which demonstrated that beetle assemblages in our control units accurately represent undisturbed primary forests in the study region as a whole (see Appendix S2, Table S2).

At each sample site, we established three fixed-width (75-m) point counts (PCs) spaced at least 170 m apart (the maximum distance between PCs within a site was 200 m) and located c. 50 m from the sampling site’s border. Each PC had four 10-min visits on 2 consecutive days and at different times of the day (from 30 min before sunrise to 10h30 and from 15h30 to 30 min before sunset). All bird surveys were conducted by one experienced observer (CBA), who recorded all observed and heard birds during each survey. The highest number of individuals recorded for a species during any of the four visits was considered the final count for that species at each PC. Vocalizations were recorded using digital audio recorders (Sound Device 701 or Sony PCM D50) and a shotgun microphone (Sennheiser ME 66), and these were further examined by two ornithologists (CBA and TVVC) to determine bird identification. All recordings are archived at the Arquivos Sonoros da Amazônia Library of the National Institute of Amazonian Research (Brazil).

Dung beetles were collected using six pitfall traps baited with c. 35 g of fresh dung (4:1 pig-to-human ratio; Marsh et al. Reference Marsh, Louzada, Beiroz and Ewers2013). Traps were spaced 100 m apart in a 2 × 3 rectangular grid and located at least 75 m away from the sampling site edges to ensure even coverage and spatial independence (Mora-Aguilar et al. Reference Mora-Aguilar, Arriaga-Jiménez, Correa, da Silva, Korasaki and López-Bedoya2023). Pitfall traps were plastic containers (19 cm diameter and 11 cm deep) buried flush with the ground, part-filled with a saline-killing solution (c. 200 mL) and protected from the rain with a plastic lid. We restricted our sample window to 24 h to minimize the probability of attracting dung beetles from outside the sample sites and logging units with different intensities (Da Silva & Hernández Reference Da Silva and Hernández2015). All trapped dung beetles were processed and identified to species level (or morphospecies level when the former level was not possible) using a key to the New World’s Scarabaeinae genera and subgenera (Boucomont Reference Boucomont1928, Génier Reference Génier1996, Canhedo Reference Canhedo2006, Vaz-de-Mello et al. Reference Vaz-de-Mello, Edmonds, Ocampo and Schoolmeesters2011, Cupello Reference Cupello2018, Cupello & Vaz-de-Mello Reference Cupello and Vaz-de-Mello2018, González-Alvarado & Vaz-de-Mello Reference González-Alvarado and Vaz-de-Mello2021). Voucher specimens are deposited at the Federal University of Lavras (UFLA/CREN: Coleção de Referência de Escarabeíneos Neotropicais) and the Entomological Section of the Zoological Collection in the Federal University of Mato Grosso (Brazil).

Amazonian fauna taxonomic and functional responses to selective logging

To investigate how bird and dung beetle functional and taxonomic diversity respond to logging intensification and time since disturbance (first question), taxonomic diversity metrics were the total abundance, species richness and biomass for each sampling site (see details in Fig. 1). To estimate the biomass of each taxonomic group, we used the species community-weighted mean body mass (CWMbm), which was calculated by averaging the body mass of each species weighted by its relative abundance and summing these values for all species present at each sampling site (for more details, see Lavorel et al. Reference Lavorel, Grigulis, McIntyre, Williams, Garden and Dorrough2008).

For functional diversity, we used the following bird attributes: activity period, foraging stratum, feeding guild and body mass. Species-level body mass and activity period data were obtained from EltonTraits 1.0 (Wilman et al. Reference Wilman, Belmaker, Simpson, de la Rosa, Rivadeneira and Jetz2014). Foraging strata, feeding guilds and other missing information were extracted from Terborgh et al. (Reference Terborgh, Robinson, Parker, Munn and Pierpont1990) and Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Stouffer and Vargas2011). For dung beetles, we obtained activity period, dietary preference, body mass and functional traits from previous experiments conducted in our study region (Beiroz et al. Reference Beiroz, Slade, Barlow, Silveira, Louzada and Sayer2017, Reference Beiroz, Sayer, Slade, Audino, Braga and Louzada2018). Dung beetle species-level body mass was measured as the mean dry mass of sampled individuals. Nesting behaviour (e.g., rollers, tunnellers or dwellers) was assigned at the genus level. We adopted these bird and dung beetle functional attributes to calculate three functional metrics: (1) diversity (FDq) using Rao’s quadratic entropy index, which incorporated all mentioned traits for each taxonomic group in the ‘picante’ R package (Kembel et al. Reference Kembel, Cowan, Helmus, Cornwell, Morlon and Ackerly2010); (2) specialization (FSp), which determines the average distance of a species from the others in the functional space (Mouillot et al. Reference Mouillot, Graham, Villéger, Mason and Bellwood2013); and (3) originality (FOr), which measures redundancy or singularity (Mouillot et al. Reference Mouillot, Graham, Villéger, Mason and Bellwood2013) and was calculated by dividing the minimum functional distance of each species (>0) by the maximum overall distance in the principal coordinate analysis generated by Gower’s distance between species in each sampling site.

Partitioning Bray–Curtis dissimilarity into abundance gradients and balanced variation

To assess whether beetle and bird responses to logging and time since disturbance are driven by the loss of individuals across all species or by a non-random replacement of individuals among species (second question), average Bray–Curtis dissimilarities were calculated and compared between logged and control sites to assess the impact of logging intensification, as well as among control sites to represent natural variation in unlogged forests (i.e., control dissimilarity), which demonstrated that Bituba and Gueti had faunal assemblages with similar species compositions (see Table S3). We used the ‘betapart’ package (Baselga & Orme Reference Baselga and Orme2012) to calculate the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity partitioned into two components (Baselga Reference Baselga2017): (1) balanced (i.e., individuals’ substitution among different species) and (2) gradient (i.e., subsets resulting from individuals’ loss from one site to another across all species; see details in Appendix S2 & Fig. S1). Abundance data were log-transformed before calculating Bray–Curtis dissimilarity components.

Determining species rarity as a proxy of disturbance-sensitive species

To examine whether changes in disturbance-sensitive species influence biodiversity responses to logging and time since logging (third question), we used data from a long-term monitoring project conducted in the same concession and following standardized methodological protocols (from 2009 to 2013; see Gardner et al. Reference Gardner, Barlow, Araujo, Ávila-Pires, Bonaldo and Costa2008). Using only 2011 data for both taxa, we obtained species’ distributions and abundances beyond the logged regions and encompassing primary forests and Eucalyptus spp. plantations (Beiroz et al. Reference Beiroz, Slade, Barlow, Silveira, Louzada and Sayer2017). Our rarity index therefore is based on species’ local abundances, geographical range and habitat breadth (following Leitão et al. Reference Leitão, Zuanon, Villéger, Williams, Baraloto and Fortunel2016; see details in Appendix S3).

For each species, we calculated local abundances as the mean number of individuals excluding sites where species were not observed. The geographical range was determined using the coordinates of all sampling points where species were recorded, calculating the relative area of occurrence. If a species was sampled in up to two sampling points, we calculated the area of a 1–km buffer around the sampling points. Habitat breadth was determined using the Outlying Mean Index, which measures the species’ realized niche based on environmental conditions axes in a principal component analysis (Palomares et al. Reference Palomares, Fernández, Roques, Chávez, Silveira and Keller2016). Environmental conditions considered were annual mean temperature, temperature annual range, annual precipitation and the precipitation of the driest month from the WorldClim database with 30-s resolution (Fick & Hijmans Reference Fick and Hijmans2017), in addition to the forest classification provided by the logging concession (lowland forests, submontane forests and Eucalyptus plantations). Rarity also incorporated two field-surveyed environmental metrics: (1) canopy openness, assessed using semi-hemispheric photography at 1.5 m above ground level and Gap Light Analyser software to analyse photos (Frazer et al. Reference Frazer, Canham and Lertzman1999); and (2) soil sand content (g/kg), collected at up to 10–cm depths beside each trap and combined into a composite sample for each sample unit (for methodological details, see França et al. Reference França, Louzada and Barlow2018).

We calculated the rarity index as the mean values of the species traits weighted by their Pearson’s correlation (following Leitão et al. Reference Leitão, Zuanon, Villéger, Williams, Baraloto and Fortunel2016). Before calculating the integrative rarity index, we standardized the species traits to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 (Schielzeth Reference Schielzeth2010). This ensured that the rarity index ranged from 0 to 1, mirroring the metrics’ range. We slightly modified the index used in previous studies by subtracting our values from 1, indicating that a rarity index of 0 represents the most common species, whereas values of 1 indicate the rarest species.

Data analysis

To examine the influence of logging intensification and time since disturbance on bird and dung beetle responses (first question), we built generalized linear models (GLMs) using logging intensity, concession region (i.e., Bituba × Gueti; as a proxy of time since logging) and their interaction as our explanatory variables. For both taxa, we used the following distributions: (1) quasi-Poisson for species richness; (2) negative binomial for abundances; and (3) Gaussian for biomass, FDq, FSp and FOr (see details in Table S4). To assess whether beetle and bird responses to logging intensification and time since disturbance were driven by abundance losses or replacements (second question), we applied GLMs having total Bray–Curtis dissimilarity and their balanced and gradient components as response variables. A Gaussian model was fitted for the beetle Bray–Curtis gradient component, while a Gamma distribution was used for all of the other models with beetle and bird Bray–Curtis dissimilarities. Finally, to investigate the influence of logging intensification and time since disturbance on disturbance-sensitive bird and beetle species (third question), we used the community-weighted rarity index per sampling unit as the response variable and a linear model (LM) with a Gaussian error distribution. All analyses were run in R software (R Core Team 2023). See Table S4 (Appendix S2) for a summary of models and variables for each research question.

Results

We recorded 5081 bird records and collected 7892 dung beetles from 182 and 45 species, respectively. We found 44.7 ± 2.8 and 41.4 ± 8.2 (mean ± SD) bird species in control and logged sites, respectively. For dung beetles, we registered 193.7 ± 56.7 and 161.0 ± 99.4 individuals and 20.7 ± 1.7 and 19.0 ± 3.8 species in control and logged sites, respectively.

Logging intensification

We found a significant negative effect of logging intensification on dung beetle abundance (χ2 = 11.13, p = 0.0008; Fig. 3a), species richness (F1,46 = 11.13, p = 0.01; Fig. 3b), functional specialization (F1,46 = 9.68, p = 0.0032; Fig. 3c) and functional originality (F1,46 = 4.42, p = 0.04; Fig. 3d). We also observed that logging intensification enhanced taxonomic dissimilarity (χ2 = 0.67, p = 0.0016; Fig. 3e) and the Bray–Curtis gradient component (χ2 = 4.62, p = 0.016; Fig. 3f). Except for a negative effect on bird body mass (F1,46 = 3.91, p = 0.05; Fig. 3g), we did not find any significant effects of logging intensification on bird responses.

Figure 3. (a) Dung beetle abundance, (b) species richness, (c) functional specialization, (d) functional originality, (e) Bray–Curtis dissimilarity, (f) Bray–Curtis gradient component and (g) bird body mass responses to selective logging intensification (i.e., number of removed trees per hectare) in the Brazilian Amazon. Grey dots show 10-ha sampled units with different logging intensities and the grey shadow in regression lines represents their 95% confidence intervals. See Fig. S1 for details on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity components.

Time since logging

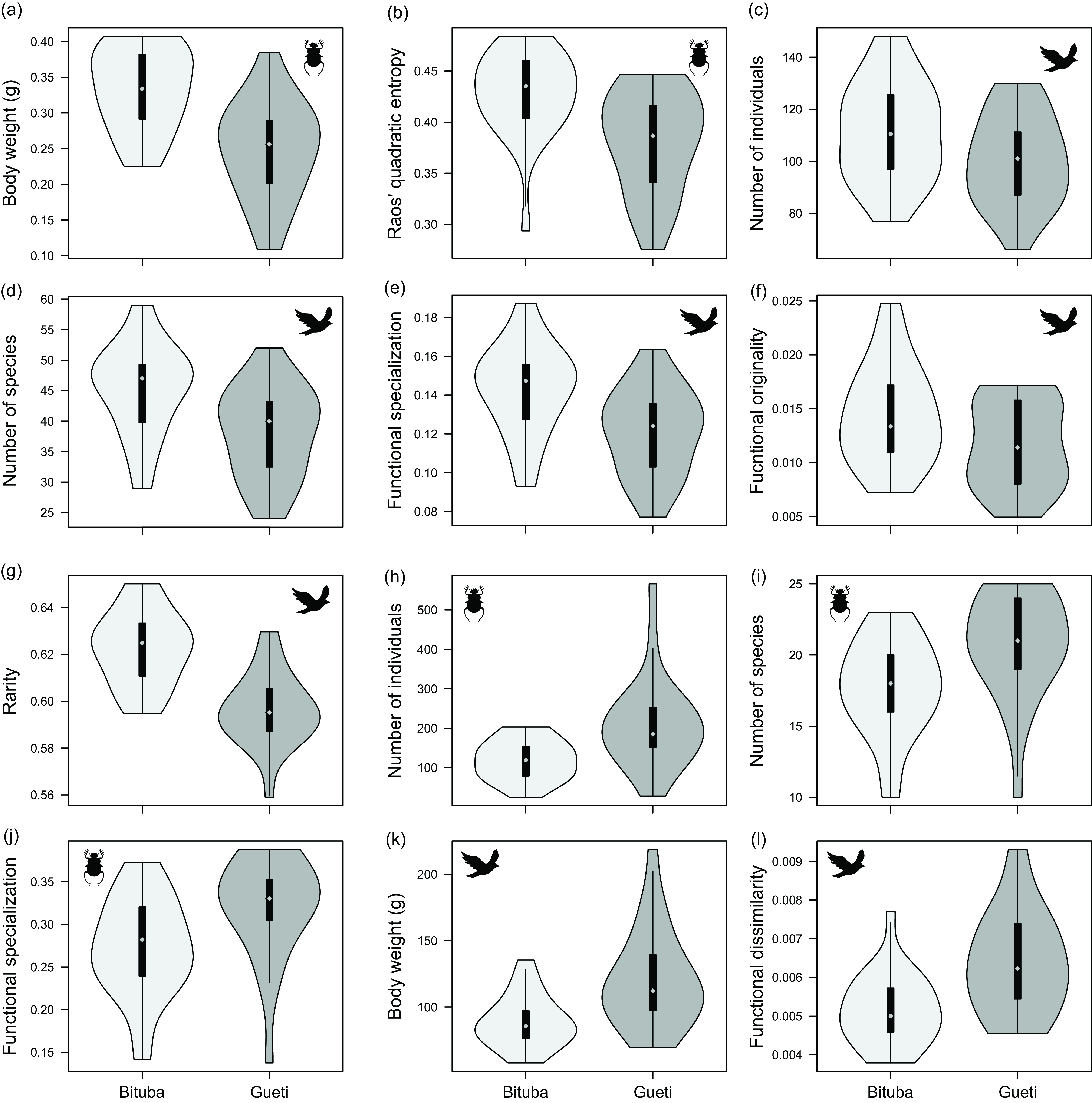

We observed higher dung beetle biomass (χ2 = 21.5, p ≤ 0.0001; Fig. 4a) and functional diversity (χ2 = 13.14, p = 0.0007; Fig. 4b), as well as bird abundance (χ2 = 4.8, p = 0.0008; Fig. 4c), species richness (χ2 = 11.07, p = 0.001; Fig. 4d), functional specialization (χ2 = 11.51, p = 0.001; Fig. 4e), functional originality (χ2 = 5.25, p = 0.026; Fig. 4f) and species rarity (χ2 = 40.93, p ≤ 0.0001; Fig. 4g) within forests with greater recovery times since selective logging. By contrast, recently logged forests had higher dung beetle abundance (χ2 = 11.87, p = 0.0006; Fig. 4h), species richness (χ2 = 6.19, p = 0.016; Fig. 4i) and functional specialization (χ2 = 5.53, p = 0.02; Fig. 4j), as well as higher bird biomass (χ2 = 13.93, p = 0.0005; Fig. 4k) and functional dissimilarity (χ2 = 0.54, p = 0.0001; Fig. 4l).

Figure 4. Dung beetle and bird responses to time since selective logging in the Brazilian Amazon. Bituba (light grey) and Gueti (dark grey) forests were selectively logged in 2006 and 2009, c. 5.0–6.0 and 1.5–2.0 years before data collection, respectively. (a) Dung beetle body weight, (b) dung beetle Raos’ quadratic entropy, (c) number of bird individuals, (d) number of bird species, (e) bird functional specialization, (f) bird functional originality, (g) bird rarity, (h) number of dung beetle individuals, (i) number of dung beetle species, (j) dung beetle functional specialization, (k) bird body weight and (l) bird functional dissimilarity.

Discussion

We provide novel empirical evidence of the impacts of selective logging on tropical fauna biodiversity. Logging intensification drove declines in bird body mass and dung beetle taxonomic and functional responses whilst increasing dissimilarity in dung beetle species composition. We also demonstrate that recently logged forests displayed lower dung beetle body mass and functional diversity, as well as lower bird richness, functional specialization, originality and rare species. Combined, these findings support previous research demonstrating that logging intensification impacts can vary among biodiversity groups (Burivalova et al. Reference Burivalova, Şekercioğlu and Koh2014) whilst highlighting the importance of post-logging time for biodiversity recovery in tropical American forests.

Logging intensification’s impacts on tropical fauna vary across taxa and biodiversity metrics

We provide empirical evidence that dung beetles may be more sensitive to selective logging compared to birds; most dung beetle taxonomic and functional metrics varied across our logging intensification gradient, but only bird body mass showed a significant decline with increasing logging intensity (Fig. 3). The steeper beetle responses could be attributed to their heightened sensitivity to environmental changes, including warmer and drier microclimates in logged forests (Asner et al. Reference Asner, Broadbent, Oliveira, Keller, Knapp and Silva2006, Yamada et al. Reference Yamada, Yoshioka, Hashim, Liang and Okuda2014). Dung beetles may also face increased competition for limited food resources (Horgan & Fuentes Reference Horgan and Fuentes2005), potentially impacted by logging’s negative effects on mammals (Felton et al. Reference Felton, Felton, Foley and Lindenmayer2010, Poulsen et al. Reference Poulsen, Clark and Bolker2011). Additionally, changes in sunlight exposure and drying winds, particularly in forest gaps that are more common in highly and recently logged forests (Asner et al. Reference Asner, Keller and Silva2004, Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Fischer, Coomes and Jucker2023), could affect the quality of food resources for dung beetles. Consequently, selective logging may lead to the loss of forest interior-specialist dung beetle species (as supported by observed changes in beetle functional specialization; Fig. 3c), resulting in decreased overall dung beetle diversity as logging intensity and its impacts on microclimate increase (Hosaka et al. Reference Hosaka, Niino, Kon, Ochi, Yamada and Fletcher2014, Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Finan, Graham, Larsen, Wilcove and Hsu2017). The observed increases in Bray–Curtis dissimilarity and the abundance gradient component further support logging-induced effects on beetle assemblage dissimilarities being primarily driven by the loss of individuals rather than their substitution across sampled sites (Baselga Reference Baselga2017).

There are three potential reasons for the impacts of logging intensification on bird species richness, composition and functional diversity metrics being masked. Firstly, our study region consists mainly of primary forests with minimal disturbance levels (Hethcoat et al. Reference Hethcoat, Edwards, Carreiras, Bryant, França and Quegan2019), providing resources for birds’ foraging and breeding (Kupfer et al. Reference Kupfer, Malanson and Franklin2006) whilst facilitating the dispersal of individuals from undisturbed to logged forests (Gilroy & Edwards Reference Gilroy and Edwards2017). Secondly, the relatively low logging intensities in our forest concession compared to other tropical regions could contribute to maintaining avian biodiversity (Wunderle et al. Reference Wunderle, Henriques and Willig2006). Low-intensity logging and RIL have been associated with increased flowering and fruiting, supporting generalist species’ ability to forage in logged forests (Peh et al. Reference Peh, Jong, Sodhi, Lim and Yap2005, Burivalova et al. Reference Burivalova, Şekercioğlu and Koh2014). Lastly, our findings could also be influenced by methodological biases related to the lack of pre-logging baseline data (Christie et al. Reference Christie, Abecasis, Adjeroud, Alonso, Amano and Anton2020) and the easier bird detection in logged tropical forests (Woltman Reference Woltman2003). Nonetheless, our findings align with previous studies on temporal changes in bird assemblages (Wunderle et al. Reference Wunderle, Henriques and Willig2006) and demonstrate their high functional redundancy in Amazonian forests (Hidasi-Neto et al. Reference Hidasi-Neto, Barlow and Cianciaruso2012).

Post-logging recovery of tropical biodiversity fauna

Forests that were sampled some 5–6 years after selective logging exhibited higher bird species richness, abundance, functional specialization and functional originality, as well as higher dung beetle body mass and functional diversity (Fig. 4). While underscoring the positive relationship between post-disturbance recovery time and biodiversity in logged tropical forests, these findings may be explained by the availability of food resources for faunal communities – for example, forest structure can recover with time since logging (Broadbent et al. Reference Broadbent, Zarin, Asner, Peña-Claros, Cooper and Littel2006), which may result in higher rates of energy flow (Malhi et al. Reference Malhi, Riutta, Wearn, Deere, Mitchell and Bernard2022), flowering and fruiting (Ewers et al. Reference Ewers, Boyle, Gleave, Plowman, Benedick and Bernard2015) within older logged forests. Moreover, the higher functional specialization, originality and rarity of birds in older logged forests suggest that functionally unique and rare species may also increase with post-logging forest recovery. These results also indicate a reduced functional space in recently logged forests, probably due to logging-induced environmental filters to sensitive species (Baraloto et al. Reference Baraloto, Hardy, Paine, Dexter, Cruaud and Dunning2012, Ding et al. Reference Ding, Zang, Lu and Huang2019). Rare species are often the first to be lost following disturbances, attributable to their sensitivity to environmental changes (Montejo-Kovacevich et al. Reference Montejo-Kovacevich, Hethcoat, Lim, Marsh, Bonfantti and Peres2018) and smaller habitat ranges and population sizes (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Williams, VanDerWal, Isaac, Shoo and Johnson2009, Harnik et al. Reference Harnik, Simpson and Payne2012). Their unique combination of functional traits (Umaña et al. Reference Umaña, Zhang, Cao, Lin and Swenson2017) and position at the edge of community functional spaces (Leitão et al. Reference Leitão, Zuanon, Villéger, Williams, Baraloto and Fortunel2016) further contribute to the observed decrease in functional specialization and originality in recently logged forests.

Implications for biodiversity research, conservation and sustainable forest management

Understanding the trade-offs between the conservation value and timber production in Amazonian logged forests is globally significant. The region holds the largest remaining stock of tropical timber and over 10% of known species worldwide (Guayasamin et al. Reference Guayasamin, Ribas, Carnaval, Carrillo, Hoorn and Lohmann2021). As African and Asian timber stocks decline, the demand for tropical hardwood is expected to increase, putting pressure on expanding timber concessions and intensifying harvesting in Amazonia’s forests.

Our study provides valuable insights for future research, sustainable management and biodiversity conservation in tropical logged forests. The heightened sensitivity of dung beetles compared to birds demonstrates the relevance of research investigating multi-taxa responses to forest disturbances (Pardini et al. Reference Pardini, Faria, Accacio, Laps, Mariano-Neto and Paciencia2009, Silveira et al. Reference Silveira, Louzada, Barlow, Andrade, Mestre and Solar2016), emphasizing that conservation and management practices should consider the varying responses of different taxa to enhance biodiversity outcomes in tropical logged forests. Yet, current environmental regulations in the Brazilian Amazon focus solely on tree populations (CONAMA, Resolution 1/2015), overlooking the cascading effects of harvest operations on faunal assemblages, soil biodiversity and ecological processes. Given that timber concessions in Brazil’s public forests cover 1.6 million ha, with an estimated potential for 35 million ha (Sist et al. Reference Sist, Piponiot, Kanashiro, Pena-Claros, Putz and Schulze2021), there is a pressing need to improve forest conservation legislation and its enforcement by addressing the consequences of logging on various biodiversity groups and their associated ecological processes (França et al. Reference França, Frazão, Korasaki, Louzada and Barlow2017).

Our findings indicate that older logged forests are likely to recover rare and disturbance-sensitive species when compared to recently logged forests. This result, combined with the large amount of old-growth forests within our study region (Hethcoat et al. Reference Hethcoat, Edwards, Carreiras, Bryant, França and Quegan2019), elucidates the relevance of maintaining logged forests free of additional disturbances and designing concessions that incorporate undisturbed patches and logged forests at varying post-harvesting ages to enhance concession-level forest biodiversity and recovery (Chazdon Reference Chazdon2003). Future research should explore how concession design and selective logging practices can further improve the recovery of logging-sensitive species across a longer post-logging timeframe, ideally through a before–after control–impact approach (Christie et al. Reference Christie, Abecasis, Adjeroud, Alonso, Amano and Anton2020). This knowledge would advance understanding of the conservation value of production forests, providing guidance for cost-effective post-harvest interventions aimed at conserving biodiversity and restoring the environmental resilience of selectively logged tropical forests (Cerullo & Edwards Reference Cerullo and Edwards2019).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892923000334.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Jari Florestal for logistical support and soil texture analyses. We owe special thanks to Edivar Correa, Jucelino dos Santos and Maria Orlandina for their invaluable assistance during fieldwork; Amanda P Arcanjo for supporting dung beetle identifications; and Vanesca Korasaki, Jos Barlow and Toby Gardner for support with funding and experimental design. We are also grateful to Alexander Lees, two reviewers and Nicholas Polunin for their valuable contributions that improved our manuscript.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: FMF and WB. Investigation: FMF, WB, CBA and TVVC. Data curation: FMF, WB, CBA, TVVC and FZVM. Formal analysis: FMF and WB. Funding acquisition: FZVM, JMS and JL. Resources: FZVM and JL. Project administration: FMF, WB, CBA and JMS. Writing – original draft: FMF and WB. Writing – review & editing: FMF, WB, TVVC and JMS. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Financial support

This research was funded by grants from the Brazilian Research Council (CNPq): MCTI/CNPq/FAPs (No. 34/2012) and CNPq-PELD site 23 (PELD-JARI; 403811/2012-0). FMF acknowledges funding provided by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq; Synergize: MCTIC/Sinbiose 442354/2019-3) and the University of Bristol via PolicyBristol (SynPAm; ID: 1989427), Climate and Net Zero Impact Awards (Scaling-up TAOCA; ID: 170839), Cabot Seedcorn 2023 (Voices of Amazonia; ID: 2258319) and Elizabeth Blackwell Institute Rapid Research Funding (CO-SPACE; ID: 2208557) during data analysis and manuscript writing; and funding that was awarded by CAPES (BEX5528/13-5) and CNPq (383744/2015-6) during the fieldwork. FMF, WB, FZVM and JL also acknowledge CNPq for funding support through the INCT-SinBiAm (INCT 406767/2022-0) and PPBio-AmOr networks (441257/2023-2). FZVM thanks CNPq for the 1A productivity fellowship (313397/2021-0).

Competing interests

No potential competing interests were reported by the authors.

Ethical standard

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with applicable national and institutional ethical guidelines. Insect surveys occurred with appropriate state and federal permits (Brazil: SISBIO #1620-3/10068). Datasets used in this manuscript are available at the TAOCA biodiversity platform (https://www.taoca.net/).