INTRODUCTION

Globally, habitat transformation is causing unprecedented loss of biodiversity (Butchart et al. Reference Butchart, Walpole, Collen, van Strien, Scharlemann, Almond, Baillie, Bomhard, Brown and Bruno2010). In turn, this affects ecosystem functioning and stability, the flow of ecosystem services and human well-being (Foley et al. Reference Foley, DeFries, Asner, Barford, Bonan, Carpenter, Chapin, Coe, Daily, Gibbs, Helkowski, Holloway, Howard, Kucharik, Monfreda, Patz, Prentice, Ramankutty and Snyder2005; Cardinale et al. Reference Cardinale, Duffy, Gonzalez, Hooper, Perrings, Venail, Narwani, Mace, Tilman and Wardle2012). Conflicts between biodiversity conservation and human development needs, which are driving habitat transformation and biodiversity loss, are difficult to resolve (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Pringle, Ranganathan, Boggs, Chan, Ehrlich, Haff, Heller, Al-khafaji and Macmynowski2007).

In order to identify beneficial solutions for all involved, conservation agendas are focusing on ecosystem services (Balvanera et al. Reference Balvanera, Daily, Ehrlich, Ricketts, Bailey, Kark, Kremen and Pereira2001; Armsworth et al. Reference Armsworth, Chan, Daily, Ehrlich, Kremen, Ricketts and Sanjayan2007). Ecosystem services are ‘the benefits people obtain from ecosystems’ (MA [Millennium Ecosystem Assessment] 2005; p.1), which depend on biodiversity (Mace et al. Reference Mace, Norris and Fitter2012) and sustain human well-being in everyday life (MA 2005). A number of assessments have combined biodiversity conservation and sustainable development objectives (see White et al. Reference White, Halpern and Kappel2012; Bateman et al. Reference Bateman, Harwood, Mace, Watson, Abson, Andrews, Binner, Crowe, Day and Dugdale2013). However, studies on the spatial congruence between ecosystem services and biodiversity show that priority areas do not always match (see for example, Chan et al. Reference Chan, Shaw, Cameron, Underwood and Daily2006; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Armsworth, Eigenbrod, Thomas, Gillings, Heinemeyer, Roy and Gaston2009; Egoh et al. Reference Egoh, Reyers, Rouget, Bode and Richardson2009; Di Minin et al. Reference Di Minin, Fraser, Slotow and MacMillan2013 b). In addition, gaps in ecosystem services science (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Mooney, Agard, Capistrano, DeFries, Díaz, Dietz, Duraiappah, Oteng-Yeboah, Pereira, Perrings, Reid, Sarukhan, Scholes and Whyte2009), and lack of political support (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Pringle, Ranganathan, Boggs, Chan, Ehrlich, Haff, Heller, Al-khafaji and Macmynowski2007), challenge implementation on the ground (Tallis et al. Reference Tallis, Kareiva, Marvier and Chang2008). Consequently, new information is needed to evaluate ecosystem services (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Mooney, Agard, Capistrano, DeFries, Díaz, Dietz, Duraiappah, Oteng-Yeboah, Pereira, Perrings, Reid, Sarukhan, Scholes and Whyte2009) and assess their contribution to help identify strategies that benefit both biodiversity conservation and human well-being (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Pringle, Ranganathan, Boggs, Chan, Ehrlich, Haff, Heller, Al-khafaji and Macmynowski2007; Norgaard Reference Norgaard2010; Saunders Reference Saunders2013).

Ecosystems provide material (for example, water availability, crop diversity, and climate regulation) and non-material (such as cultural, recreational, and spiritual) benefits to people (MA 2005). The evaluation of material services is crucial to inform the society about the importance of natural capital (Costanza & Daly Reference Costanza and Daly1992). Importantly, the evaluation of material services provides information that can be used to inform conservation planning (Egoh et al. Reference Egoh, Rouget, Reyers, Knight, Cowling, van Jaarsveld and Welz2007; Tallis et al. Reference Tallis, Kareiva, Marvier and Chang2008) and decision-making processes (Daily et al. Reference Daily, Polasky, Goldstein, Kareiva, Mooney, Pejchar, Ricketts, Salzman and Shallenberger2009; Bateman et al. Reference Bateman, Harwood, Mace, Watson, Abson, Andrews, Binner, Crowe, Day and Dugdale2013). However, the evaluation of the intangible benefits of most of the non-material, cultural, services has been largely overlooked (MA 2005).

By bridging the gap between different academic disciplines, the evaluation of cultural services may help inform real-world decision-making (Milcu et al. Reference Milcu, Hanspach, Abson and Fischer2013; Saunders Reference Saunders2013). Among cultural services, ‘sense of place’, which people develop in connection with ecosystems (Russell et al. Reference Russell, Guerry, Balvanera, Gould, Basurto, Chan, Klain, Levine and Tam2013), has been indicated as a concept that may potentially bridge existing gaps between ecosystem science and environmental management (Williams & Stuart 1998). By understanding, anticipating, and responding to peoples' relationships with places, managers are better equipped to develop management activities that will avoid conflict and gain public support (Williams & Stuart 1998). Sense of place is, however, one of the most neglected cultural services and information on how to integrate it into conservation decision-making is scarce (MA 2005).

We reviewed the existing literature on sense of place, with an aim to identify the potential contributions of sense of place to both human well-being and biodiversity conservation. We started by defining sense of place in fields outwith conservation science. We reviewed the literature to: (1) clarify the importance (social and economic benefits) of sense of place as an ecosystem service, (2) discuss how sense of place has been accounted for in conservation science, and (3) identify how to further integrate sense of place values into conservation decision-making.

METHODS

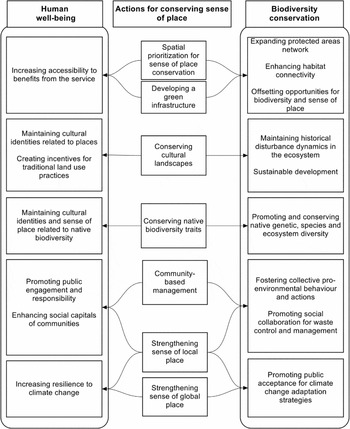

To explore the implications of sense of place in biodiversity conservation, we searched existing publications on sense of place, using the Thomson Reuters’ Web-of-Science database (accessed 1 September 2014). Since the term ‘place attachment’ has also been used as an alternative term for sense of place (Brown & Raymond Reference Brown and Raymond2007), this was also included in our literature search. We used the phrase ‘TOPIC: ((‘sense of place’) OR (‘place attachment’))’ as a baseline for the search (1441 results). In order to select papers that looked at sense of place in biodiversity conservation, we also included in the search AND ‘conservation’ as TOPIC (114 results). We subsequently refined the results by using ‘biodiversity’ (21 results) and ‘ecosystem service*’ (11 results) and ‘management’ (57 results). We thus identified a total of 62 unique articles (see Supplementary material for the complete list); those that were most relevant are cited. In each of the studies, we looked at (1) implications for human well-being and biodiversity conservation; and (2) insights addressing gaps in conservation science. Next, we identified gaps in conservation science, and issues related to the integration of sense of place in conservation decision making. The resulting information on gaps was used to develop a conceptual framework (Fig. 1), summarizing insights gained from other disciplines, and emphasizing ways sense of place may be incorporated in conservation decision-making to promote positive benefits for both biodiversity conservation and human well-being.

Figure 1 Conceptual framework incorporating sense of place in conservation decision-making; pathways outline potential ways to mitigate threats to biodiversity conservation.

Sense of place

Sense of place represents all dimensions of human perception and interpretation of the environment in an emotional, spiritual and cognitive way (Tuan Reference Tuan1977; Jorgensen & Stedman Reference Jorgensen and Stedman2006). People develop a sense of place as a result of biological, individual and sociocultural processes that take place while people experience (namely by interacting, knowing, perceiving, or living; Russell et al. Reference Russell, Guerry, Balvanera, Gould, Basurto, Chan, Klain, Levine and Tam2013) the physical environment (Table 1). In the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, sense of place was referred to as the relationship between people and ecosystems, this relationship representing a natural condition indispensable for human existence (MA 2005). However, the concept has had a long history of application in multiple disciplines, and has only recently been recognized as an ecosystem service (MA 2005).

Table 1 Components of the development of sense of place and attributes of each component affecting peoples’ perspectives.

The terminology surrounding sense of place varies across different disciplines (Table 2). For example, in environmental psychology and sociological studies, sense of place is referred to as peoples’ attachment to, identification with, and dependence on places, and has been used to describe connections with, and perceptions of, environments affecting human behaviour (Stedman Reference Stedman2002). In human geography, sense of place entails all the meanings that people assign to places, which define the perceived value of their attributes and appearance (Tuan Reference Tuan1990). In health sciences, peoples’ connection with the natural environment has been described as a biologically-based condition, essential for human health (such as mental health and recovery; Maller et al. Reference Maller, Townsend, Pryor, Brown and St Leger2006). In ecosystem management, sense of place refers to public attitudes toward the environment and its management (for example in urban planning, natural resource management, and land-use planning), and has been used to assess social impacts of specific management decisions (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Wallner and Hunziker2009). Finally, sense of place plays a key role in tourism development, and has been studied to understand its contribution to tourists’ perceived value of experience, expectations, and satisfaction in relation to a specific destination (Kil et al. Reference Kil, Holland, Stein and Ko2012).

Table 2 Concepts related to sense of place that have been used in different disciplines to describe various aspects of the human relationship with the natural environment.

Health benefits

Contact with nature promotes physical, mental and psychological well-being, enhancing peoples’ assessment of quality of life in ways that cannot be satisfied by alternative means (Abraham et al. Reference Abraham, Sommerhalder and Abel2010; Maller et al. Reference Maller, Townsend, Pryor, Brown and St Leger2006; Russell et al. Reference Russell, Guerry, Balvanera, Gould, Basurto, Chan, Klain, Levine and Tam2013). For instance, exposure to nature has been shown to promote recovery from surgery (Ulrich Reference Ulrich1984) and lower blood pressure (Lohr & Pearson-Mims Reference Lohr and Pearson-Mims2006); relieve stress (Leather et al. Reference Leather, Pyrgas, Beale and Lawrence1998); increase positive mood (Maller et al. Reference Maller, Townsend, Pryor, Brown and St Leger2006); reduce mental fatigue (Staats et al. Reference Staats, Kieviet and Hartig2003); reduce crime and the tendency for aggressive behaviour (Kuo & Sullivan Reference Kuo and Sullivan2001); promote social integration (Kweon et al. Reference Kweon, Sullivan and Wiley1998); and contribute to the integrity of a personal or community identity (Horwitz et al. Reference Horwitz, Lindsay and O'Connor2001; Maller et al. Reference Maller, Townsend, Pryor, Brown and St Leger2006). These benefits are received by people everywhere, by interacting with nature in a variety of environments, from urban areas (such as public gardens and parks; Tzoulas et al. Reference Tzoulas, Korpela, Venn, Yli-Pelkonen, Kaźmierczak, Niemela and James2007), to countryside (for example cultural landscapes; Phillips Reference Phillips1998) and natural environments (or wilderness; Fredrickson & Anderson Reference Fredrickson and Anderson1999). For example, experiencing solitude in wilderness areas enhances self-perception, personal fulfilment and promotes emotional, physical and intellectual improvements (Fredrickson & Anderson Reference Fredrickson and Anderson1999). Experiencing wilderness has been used as a therapy for rehabilitating adolescents with emotional and behavioural problems (such as impulsivity, suicidal thoughts, and drug and alcohol use; Harper et al. Reference Harper, Russell, Cooley and Cupples2007). Conversely, urban environments seem to be associated with a number of negative effects on human health. Being born and raised in an urban environment, for example, increases individual risk for anxiety, and depressive and psychotic disorders (Pedersen & Mortensen Reference Pedersen and Mortensen2001; Weich et al. Reference Weich, Twigg and Lewis2006).

Moreover, people obtain benefits by contact with nature either directly, for example having indoor plants at the workplace (Larsen et al. Reference Larsen, Adams, Deal, Kweon and Tyler1998), a view from a window (Ulrich Reference Ulrich1984; Leather et al. Reference Leather, Pyrgas, Beale and Lawrence1998), and/or actively experiencing nature through recreation, or indirectly by knowing its existence in the world (Russell et al. Reference Russell, Guerry, Balvanera, Gould, Basurto, Chan, Klain, Levine and Tam2013). In particular, understanding sense of place as self-perception in a global environment has been suggested as critical for further studies, as it amplifies the importance of sense of place benefits from a local to a global scale (Devine-Wright Reference Devine-Wright2013).

Economic benefits

In economics, ecosystems are referred to as ‘natural capital’ and are evaluated according to the goods and services they provide to individuals and societies (Costanza & Daly Reference Costanza and Daly1992). The economic values of sense of place have not yet been assessed, resulting in an incomplete evaluation of the natural capital (MA 2005). The economic value of sense of place, as for other cultural services (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Satterfield and Goldstein2012), has been overlooked due to the difficulties related to its quantitative assessment (Williams & Stewart Reference Williams and Stewart1998).

Cultural services have been mainly evaluated for their recreational and aesthetic services (see Chan et al. Reference Chan, Shaw, Cameron, Underwood and Daily2006; Bateman et al. Reference Bateman, Harwood, Mace, Watson, Abson, Andrews, Binner, Crowe, Day and Dugdale2013), neglecting the sense of place value (MA 2005). For example, the aesthetic perception of ecosystem is influenced by components of attachment and emotions (Ulrich Reference Ulrich, Altman and Wohlwill1983), which might be related to observers’ expressions of its sense of place. Moreover, sense of place has been shown to drive tourists’ preferences for the choice of destination (Um & Crompton Reference Um and Crompton1990), and the intention to revisit (Kil et al. Reference Kil, Holland, Stein and Ko2012). However, there is no empirical evidence about the ability of aesthetic and recreational values to act as surrogates of sense of place in the assessment of the natural capital. In other words, the use of these values to assess the economic importance of ecosystems may overlook other aspects that sense of place in turn entails.

Sense of place includes other aspects of economic benefits, which are not confined to recreational and aesthetic values. For example, contact with nature at the workplace increases work productivity (Leather et al. Reference Leather, Pyrgas, Beale and Lawrence1998) and reduces health care costs by preventing mental illness (Dewa et al. Reference Dewa, Lesage, Goering and Caveen2004). Moreover, the improvement of social connections (Fredrickson & Anderson Reference Fredrickson and Anderson1999), as a result of sense of place development, enhances the value of social capital (namely social collaborations that encourage collective and productive activities; Lewicka Reference Lewicka2005), by encouraging interpersonal bonds between people in groups and communities (Pretty & Ward Reference Pretty and Ward2001). This strengthens peoples’ commitment to places, enhancing pro-environmental behaviour, responsible use of resources and waste reduction (Pretty & Ward Reference Pretty and Ward2001; Ramkissoon et al. Reference Ramkissoon, Weiler and Smith2012).

Use in biodiversity conservation and management

Sense of place plays a key role in predicting and promoting public support for conservation in diverse socioecological contexts (Garcia-Llorente et al. Reference Garcia-Llorente, Martín -Lopez, Iniesta-Arandia, Lopez-Santiago, Aguilera and Montes2012; Lokhorst et al. Reference Lokhorst, Hoon, le Rutte and de Snoo2014). In conservation science, sense of place has been explored as part of attitudes toward accepting conservation policies (for example, conservation easements in private lands; Farmer et al. Reference Farmer, Knapp, Meretsky, Chancellor and Fischer2011), and supporting environmental conservation (Garcia-Llorente et al. Reference Garcia-Llorente, Martín -Lopez, Iniesta-Arandia, Lopez-Santiago, Aguilera and Montes2012; Lokhorst et al. Reference Lokhorst, Hoon, le Rutte and de Snoo2014). Connection to nature increases peoples’ perceptions of sense of place, promoting personal involvement in conservation (Lokhorst et al. Reference Lokhorst, Hoon, le Rutte and de Snoo2014). In urban areas, green spaces (like public parks, private gardens, or allotments for horticulture) provide access to nature and sense of place (van Riper et al. Reference van Riper, Kyle, Sutton, Barnes and Sherrouse2012; Meurk et al. Reference Meurk, Blaschke, Simcock and Dymond2013), increasing awareness for environmental conservation (Bendt et al. Reference Bendt, Barthel and Colding2013), and social collaboration for their management (Andersson et al. Reference Andersson, Barthel and Ahrne2007; van Wyk et al. Reference van Wyk, Breen and Freimund2014). Moreover, the conservation of soundscapes related to sense of place (such as natural quietness or the sounds of wildlife) may be a way to alleviate human pressure on ecosystems and promote biodiversity conservation (Dumyahn & Pijanowski Reference Dumyahn and Pijanowski2011). Communities that perceived such values and understood the threats to sense of place were helpful in informing land-use planning (Brown & Raymond Reference Brown and Raymond2007), and identifying sites of environmental concern (Raymond et al. Reference Raymond, Bryan, MacDonald, Cast, Strathearn, Grandgirard and Kalivas2009).

One of the main issues hindering the integration of sense of place into ecosystem management is the high variability in how people perceive the environment (which may vary according to cultural background or personal experience; Borrie & Birzell Reference Borrie, Birzell, Friedmund and Cole2001). Insights designed to overcome this issue may be found in previous studies (see Sevenant & Antrop Reference Sevenant and Antrop2010; Di Minin et al. Reference Di Minin, Fraser, Slotow and MacMillan2013 a), where latent class analysis was used to account for heterogeneity when exploring people preferences for environmental attributes. A latent class model implies that preferences are not unique to individuals, but belong to a finite and identifiable number of homogeneous classes of preferences. Individual membership of a class is explained by the sociodemographic profile (Boxall & Adamowicz Reference Boxall and Adamowicz2002). However, the application of latent class modelling to explain variability in sense of place perceptions still needs to be explored.

Another issue is related to the unclear relationship between sense of place and biodiversity (Williams & Stuart 1998). Horwitz et al. (Reference Horwitz, Lindsay and O'Connor2001) stated that biodiversity, and its spatially distinctive features (such as species endemism, genetic diversity, and species abundance), is essential if ecosystems are to provoke attachment and stimulate an individual's identification with a particular place. Attractive landscapes elicit stronger emotional responses (Kaltenborn Reference Kaltenborn1998; Larson et al. Reference Larson, De Freitas and Hicks2013), while interest in a particular species (such as charismatic megafauna) or ecosystems (like wilderness areas or national parks) is positively related to peoples’ attachment to and willingness to conserve such items (Kaltenborn Reference Kaltenborn1998; Martín-López et al. Reference Martín-López, Montes and Benayas2007). Although people recognize the intrinsic value of biological diversity (Martín-López et al. Reference Martín-López, Montes and Benayas2007), Larson et al. (Reference Larson, De Freitas and Hicks2013) found that biodiversity was not valued by people for sense of place.

Evidence suggests that playing and exploring in natural environments during childhood may lead to the development of a sense of place and raise environmental awareness (Measham Reference Measham2006). At the same time, human geographers describe sense of place as a centre of meanings developed by experiencing environments (Tuan Reference Tuan1977). While people can experience the environment through knowing, perceiving, interacting and living within it (Russell et al. Reference Russell, Guerry, Balvanera, Gould, Basurto, Chan, Klain, Levine and Tam2013), the characteristics or activities associated with natural environments (such as fishing, hunting, or beauty of landscape) are also important to establishing a sense of place (Larson et al. Reference Larson, De Freitas and Hicks2013). Biodiversity features (for example species or ecosystems), and physical attributes related to natural environments, may also affect the way people develop a sense of place.

Interests in species and landscapes are expressions of perceived benefits (such as stress relief; Hartig & Staats Reference Hartig and Staats2006) and reflect demand for cultural services (Cardinale et al. Reference Cardinale, Duffy, Gonzalez, Hooper, Perrings, Venail, Narwani, Mace, Tilman and Wardle2012) like sense of place. Preferences and willingness to pay are often used to assess the economic importance of perceived values for biodiversity (Martín-López et al. Reference Martín-López, Montes and Benayas2007; Di Minin et al. Reference Di Minin, Fraser, Slotow and MacMillan2013 a), and may be explored to assess the value of sense of place for biodiversity-related experiences. There is guidance to quantitatively assess sense of place (Mendoza & Moren-Alegret Reference Mendoza and Moren-Alegret2013) and estimate the economic value of cultural services (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Satterfield and Goldstein2012). Among these, stated preferences methods (Adamowicz et al. Reference Adamowicz, Boxall, Williams and Louviere1998), used in environmental economics, have been suggested for estimating the marginal utility value of non-marketed goods and services (see Chan et al. Reference Chan, Satterfield and Goldstein2012). These approaches can be applied to assess what people value most highly for sense of place when experiencing ecosystems.

Threats, actions and sense of place

Habitat destruction, overexploitation of resources, species introduction, pollution (Diamond Reference Diamond and Nitecki1984), and climate change (Heller & Zavaleta Reference Heller and Zavaleta2009) are major drivers of biodiversity loss. We developed a conceptual framework (Fig. 1) of where sense of place could be included in conservation decision-making, and how it could be used to potentially mitigate threats to biodiversity conservation.

Sense of place development depends on the environment (namely physical features and attributes; an ecosystem's appearance and conditions), and is therefore also subject to threats affecting biodiversity. For example, land transformation occurring in ‘special’ places for sense of place (visited for recreational purposes; Kil et al. Reference Kil, Holland, Stein and Ko2012), as well as loss of access to traditional place-related lifestyles (resources harvesting or spiritual and religious symbolic meanings; Alkan et al. Reference Alkan, Korkmaz and Tolunay2009) may negatively affect individual psychology and a community's cultural values (Devine-Wright Reference Devine-Wright2009). Alien plant invasion can affect environmental features and landscape appearance (by for example increasing soil erosion; Pejchar & Mooney Reference Pejchar and Mooney2009), affecting traditional uses and customs connected to places (MA 2005). Pollution may also negatively affect sense of place, including exposure to noise pollution (Dumyahn & Pijanowski Reference Dumyahn and Pijanowski2011), or perceptions of environmental risks and concern for the future (Bickerstaff Reference Bickerstaff2004). Climate change causes environmental changes (such as rising sea levels, increasing temperatures, and extreme weather events) that alter the physical characteristics of places, causing both identity and emotional disruptions between people and ecosystems (Reser et al. Reference Reser, Morrissey, Ellul and Weissbecker2011).

Understanding how people respond to environmental changes (impacts on psychological health and well-being, response at local, national and global scales; Fresque-Baxter & Armitage Reference Fresque-Baxter and Armitage2012; Devine-Wright Reference Devine-Wright2013) is critical in order to identify management actions for adaptation (such as adjustments of structures, processes and practices). Moreover, it has the potential to provide new conceptual understandings that may help build resilience of both human and ecological systems (Devine-Wright Reference Devine-Wright2013). Integrating sense of place into ecosystem management may help identify opportunities that both mitigate threats to biodiversity, and foster human well-being in ecosystem management (Fig. 1).

Mapping communities’ sense of place (see Raymond et al. Reference Raymond, Bryan, MacDonald, Cast, Strathearn, Grandgirard and Kalivas2009) could help identify human-valued priority areas, such as ‘critical natural capital’, that may have been overlooked (Chiesura & De Groot Reference Chiesura and De Groot2003) (Fig. 1). For example, recreational sites provide access to sense of place (Kil et al. Reference Kil, Holland, Stein and Ko2012), and recreation demonstrates increased value of lands, provides competitive financial support to local stakeholders, and improves species diversity and conservation (Bateman et al. Reference Bateman, Harwood, Mace, Watson, Abson, Andrews, Binner, Crowe, Day and Dugdale2013; Di Minin et al. Reference Di Minin, Fraser, Slotow and MacMillan2013 b). Moreover, companies transforming natural habitats to alternative land uses (such as mining) could help conserve and enhance the service in other areas (McKenney & Kiesecker Reference McKenney and Kiesecker2010), thus compensating for habitat destruction (Fig. 1).

In urban planning, the development of a green infrastructure fosters psychological well-being by providing daily access to natural settings and sense of place (Maller et al. Reference Maller, Townsend, Pryor, Brown and St Leger2006; Tzoulas et al. Reference Tzoulas, Korpela, Venn, Yli-Pelkonen, Kaźmierczak, Niemela and James2007; Bendt et al. Reference Bendt, Barthel and Colding2013), while ensuring a range of ecosystem services in urban areas (such as air filtration, microclimate regulation, and noise reduction; Gaston et al. Reference Gaston, Ávila-Jiménez and Edmondson2013). Urban green spaces may enhance biodiversity through the promotion of ecological corridors and habitat connectivity (Rudd et al. Reference Rudd, Vala and Schaefer2002), as well as providing a refuge for native biodiversity (Goddard et al. Reference Goddard, Dougill and Benton2010). Psychological benefits of green spaces increase with species richness (Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Irvine, Devine-Wright, Warren and Gaston2007). Management strategies enhancing biological diversity (such as mosaics of habitat patches; Thwaites et al. Reference Thwaites, Helleur and Simkins2005) and sense of place experiences in urban green space, could contribute to both human well-being and biodiversity conservation (Fig. 1).

In rural areas, the promotion of low impact, traditional land uses (such as subsistence agriculture and small-scale farming) could also promote human well-being through sense of place (Phillips Reference Phillips1998) and sustainable development (Halladay & Gilmour Reference Halladay and Gilmour1995) (Fig. 1). Cultural landscapes represent those areas where human influence (traditional use of land and resources; Urquhart & Acott Reference Urquhart and Acott2014) has been part of ecosystem dynamics over the centuries, affecting landscape appearance (Phillips Reference Phillips1998), and species adaptation and diversity (Halladay & Gilmour Reference Halladay and Gilmour1995), while maintaining ecological processes (nutrient cycling and connectivity). This is particularly important in developing countries, where the maintenance of traditional systems would help create incentives for traditional land-use practices (Halladay & Gilmour Reference Halladay and Gilmour1995). Enhancing the value of native biodiversity for sense of place experiences could help identify critical native species, such as local cultivar varieties for agricultural practices (Perreault Reference Perreault2005) or wildlife for ecotourism (Martín-López et al. Reference Martín-López, Montes and Benayas2007; Di Minin et al. Reference Di Minin, Fraser, Slotow and MacMillan2013 a), and enhance their conservation (Fig. 1).

Globally, sense of place has the potential to contribute to actions for climate change adaptation (by increasing the network of nature reserves, alleviating pressure on land use practices, and creating culturally appropriate management interventions; Heller & Zavaleta Reference Heller and Zavaleta2009). However, of greater importance is the value of the collective actions and pro-environmental behaviours that sense of place, at a local (neighbourhood) and global scale, elicits in people (Lewicka Reference Lewicka2005). Moreover, the development of a sense of ‘global place’ (Feitelson Reference Feitelson1991) increases public concern for worldwide environmental issues, such as environmental changes (Devine-Wright Reference Devine-Wright2013) and land transformations (Foley et al. Reference Foley, Ramankutty, Brauman, Cassidy, Gerber, Johnston, Mueller, O'Connell, Ray and West2011), enhancing social collaborations and public acceptance of management intervention for global resilience goals (Devine-Wright Reference Devine-Wright2013).

Integrating sense of place in community-based management (Manzo Reference Manzo2006) and environmental impact assessment (Kaltenborn Reference Kaltenborn1998) (Fig. 1) provides an opportunity to tap into peoples’ attachment and stimulate pro-environmental behaviours (Brehm et al. Reference Brehm, Eisenhauer and Stedman2013). Involving local people in decision-making reduces conflicts with communities (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Pringle, Ranganathan, Boggs, Chan, Ehrlich, Haff, Heller, Al-khafaji and Macmynowski2007) and provides support to the long-term success of conservation actions (Tallis et al. Reference Tallis, Kareiva, Marvier and Chang2008). This is relevant in avoiding public opposition to environmental development in places considered important for sense of place (referred as the ‘not in my backyard’ [NIMBY] attitude; Devine-Wright Reference Devine-Wright2009). This reaction may be the result of imposed changes, often unrelated to local identities, and may generate conflicts between institutions, conservation and people (Devine-Wright Reference Devine-Wright2009).

While conserving sense of place may produce positive benefits (Fig. 1), peoples’ preferences for environmental attributes and qualities may, in some cases, be misaligned with biodiversity conservation objectives (Kerley et al. Reference Kerley, Geach and Vial2003). This is the case, for example, with species introduction (ornamental plants or horticulture; Reichard & White Reference Reichard and White2001), human-wildlife conflict (involving overkilling of predators to avoid livestock predation, concerns for the future, and concerns about maintaining quality of life; Treves et al. Reference Treves, Naughton-Treves and Shelley2013), or natural environment transformation (Buijs et al. Reference Buijs, Elands and Langers2009). People may perceive heavily-managed landscapes (such as commercial forests or monocultures) as aesthetically pleasing, while natural habitats (such as wetlands or deserts) may appear unattractive (Buijs et al. Reference Buijs, Elands and Langers2009). Although sense of place conservation does not necessarily match ecologically important ecosystems, peoples’ cultural values related to sense of place (Phillips Reference Phillips1998) may promote beneficial opportunities to address threats to biodiversity. As stated by Saunders (Reference Saunders2013, p. 17) ‘incorporating local cultural aspects into conservation interventions does not necessarily mean privileging local material concerns, but it would mean that local embodied experiences and interests can be more fully integrated into conservation planning decisions’.

CONCLUSION

Sense of place can potentially provide positive solutions for both human well-being and biodiversity conservation. While sense of place provides a variety of benefits to people in various contexts (Table 1), the economic value of sense of place is usually neglected. Experiencing biodiversity is also an essential component of sense of place and human well-being that needs to be further explored in future studies. Biodiversity loss (for example the loss of iconic species like rhinoceros or elephant; Di Minin et al. Reference Di Minin, Laitila, Montesino Pouzols, Leader-Williams, Slotow, Conway, Goodman and Moilanen2015) may have negative effects on sense of place, related to changes in environmental qualities and the physical characteristics of places, and loss of peoples’ identity, attachment and the meanings attributed to places. At the same time, the ‘construction’ of a sense of place could sometimes result in an increase in human disturbance and in enhanced threats to biodiversity (via habitat transformation or species introduction). Providing a sense of place experience (through recreation) should have a minimum impact on natural ecosystems.

Improved assessment and knowledge of the benefits that biodiversity-related experiences provide as a sense of place, and the inclusion of these into policies for land-use and resource management planning, could uncover positive benefits for both biodiversity conservation and human well-being. In particular, recognizing the value of sense of place in ecosystem management processes (through environmental impact assessment, land-use planning, ecotourism development, and climate change adaptation) is essential to ensure human access (through sites for outdoor activities, urban green spaces, and cultural landscapes) to sense of place benefits, while promoting biological conservation (by expanding the network of protected areas, enhancing habitat connectivity, promoting sustainable development, and gaining public support; Di Minin & Toivonen Reference Di Minin and Toivonen2015). Our research indicates that sense of place must be integral to the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (www.ipbes.net).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0376892915000314.