Introduction

The historical literature on the telecom sector has emphasized the close relations between operators and equipment suppliers. This article examines this relationship and draws a new picture of how it worked in a Norwegian context. It builds both on archival records and interviews with key actors in the sector, in particular those from Telenor, the former Norwegian public telephone operator (PTO; now a privately listed company). (I note here that at one time both the Norwegian and Swedish PTOs were named Televerket, but the Swedish PTO changed its name to Telia in 1992, and the Norwegian PTO changed its name to Telenor in 1995. For the sake of simplicity, I use Telenor and Telia.) This article aims to expand the view of how the Scandinavian telecom sector developed.

Buyer-supplier relations in broader normative narratives have often been commended as trusting, collaborative, and critical for innovations in the telecom sector. First, a public innovation narrative promotes a government’s role in corporate innovation and technological development through research funding, development contracts, and public procurement. Second, a collaborative narrative claims that buyer-supplier relations should be based on lasting and trusting collaboration. These are often based on particular narratives.Footnote 1 A case in point of the second narrative is the Telia-Ericsson relationship between the Swedish PTO and the equipment supplier, respectively. The literature and historical understanding of the Scandinavian telecom sector has been framed and dominated by this narrative.

This article tells a different story; namely, Telenor diverted drastically from this dominant narrative. Post–World War II, Telenor had difficult relations with its equipment suppliers, including high transaction costs. This contributed to Telenor’s poor reputation. This was in stark contrast to Telia, which was perceived as one of the best PTOs in world. The emergent digitalization starting in the 1970s allowed Telenor to pursue its own procurement strategy. It chose arm’s length relations with its equipment suppliers by using tenders and strict legal contracts, and by insisting that only price and quality would be criteria for procurement. This was a radical concept, given that buyer-supplier relations in the telecom industry had been both riddled with stakeholder obligations and praised for its valuable externalities, such as innovation, technological development, and employment.

The existing literature does not account for Telenor’s successful development over the last several decades to become the largest service provider in the Scandinavian telecom sector. This is a significant gap in the literature, which this article seeks to fill. The main aim of this article is to explain why Telenor chose such a different path than its Scandinavian counterparts; namely, a strict focus on price and quality with its equipment suppliers, and keeping equipment suppliers at arm’s length starting in the 1970s.

The article also seeks to answer two other questions. First, why is the Telia-Ericsson narrative so prevalent, especially after the new telecom regime made it anachronistic? One finding is that the Telia-Ericsson narrative grew stronger in the 1990s through important contributions from Swedish scholars. This was at the same time that digitalization, liberalization, and globalization transformed the telecom sector, and one effect was that buyer-supplier relations became more market-based.

Second, why has the story of Telenor not been told? It would have been fitting to call Telenor’s procurement strategy a counter narrative; however, to be a narrative, the story needs to be told. It is striking that very few historians interested in the Norwegian telecom sector know about this story, but this is also true within Telenor itself. According to Per Hansen, “historical events that are not narrated are not remembered, and therefore, do not ‘exist.’”Footnote 2 The article seeks to contribute to the discourse on narratives in business history, mainly on why some narratives become prevalent while others are not told at all.Footnote 3

The article is structured as follows. The next section reviews the relevant literature, first on narratives and then on telecoms in Scandinavia, and finally on important differences between Norway and Sweden. The second section shows how Telenor’s procurement power diminished in the postwar years due to increasing transaction costs and stakeholder obligations. The third section looks at how the public innovation narrative played out in Norwegian telecom with increased research and development. The fourth section looks at how Telenor’s transaction costs decreased starting around 1970, and how the company established links with international suppliers. The fifth section looks at how Telenor was able to exploit its procurement powers by arranging tenders to buy digital switches. The sixth section briefly looks at Telenor’s development after 1990. The conclusion returns to the research questions posed in this introduction.

Literature Review

There has been considerable interest in narratives within many academic disciplines; however, it is only recently that this tendency has reached business history.Footnote 4 Narratives are important not only to reduce complexity but also to increase sense making. As such, they share similarities with other concepts, such as culture, discourses, norms, notions, mental frameworks, models, and metaphors.Footnote 5 Moreover, the increased interest in narratives has been part of a cultural turn. Hansen says that business historians should move their “focus from whether narratives are true or false to narratives’ origins and effects.”Footnote 6 A key motivation for this change has been to tone down reductionism and instrumental rationality in business history. Moreover, narratives accentuate the social and cultural embeddedness of actors, where culture is defined as “a system of values, ideas, and beliefs which constitutes a mental apparatus for grasping reality.”Footnote 7

This article shows that Telenor followed a strategy that was founded on rationality and reductionism; that is, it chose to reduce the complexity in its procurement and buyer-supplier relations to consist of only price and quality of the product. It was a conscious decision to prevent “irrelevant” factors that could limit Telenor’s freedom of choice.Footnote 8

Companies use narratives in marketing, public relations, and “impression management”; they are integral to power games in the sense that “authoritative sensemaking relies on a compelling narrative.”Footnote 9 Both Telia and Ericsson have promoted their narrative on their respective websites and it has been repeated in commissioned history books. Narratives are often used to legitimize organizational and strategic changes. There are no signs, however, that Telenor either constructed a narrative to legitimize its strategy toward its equipment suppliers or that one developed naturally. Thus, Telenor’s strategy does not represent a counter narrative. Still, the PTO’s “rational” and reductionist approach did not develop from thin air. As Kenneth Lipartito says, “Culture inheres in all business decisions.”Footnote 10 Telenor’s approach may have emanated from or been part of a culture that was “not in the minds of the subjects.”Footnote 11 It is an interesting question whether practice theory could have exposed the culture behind Telenor’s strategy, but the sources available for this article do not allow for such an analysis. They do, however, show that Telenor implicitly and explicitly rejected numerous times both the public innovation narrative and collaborative narrative (like the one espoused by Telia-Ericsson).

One reason Telenor did not construct a strategic narrative may be that in order to be engaging, narratives should focus on a greater purpose than profits.Footnote 12 These can include trust, care, national identity, science, or progress.Footnote 13 This suggests that the aesthetic qualities of narratives are important for their continuance. In a comparison of “two discourses, the ‘knowledge-based economy’ and ‘shareholder value,’” Thompson and Harley “demonstrate that, while the [first] gained much more attention, [the latter] discourse had much more significant material outcomes.”Footnote 14 This suggests two things, the first being that the prevalence of a narrative does not necessarily translate into impact. The second is that it is more difficult for shareholder-friendly narratives to become dominant. This last point is in line with the fact that most cultural expressions of business, such as in Hollywood movies, are critical toward the shareholder value ideology.Footnote 15

Telenor suffered from a poor public image in the postwar period.Footnote 16 The organization was pictured as the incarnation of the inefficient and bureaucratic state institution and was ridiculed by comedians, so much so that its employees were reluctant to reveal their employment in social situations out of embarrassment and fear of harassment.Footnote 17 The public debates at the time and scholarly literature on Telenor accord with this opinion.Footnote 18 In a comparison of the Nordic PTOs’ procurement policies in 1985, Telenor was ranked lowest in terms of both “commercial orientation (and) technical orientation.”Footnote 19 It allegedly “had no vision for the technological development that took place,”Footnote 20 and it opposed “impulses and pressures from the industry and R&D establishment.”Footnote 21 The reason for Telenor’s alleged weakness, according to the literature, was that it did not engage with or cooperate within the industry. Hence, the literature embraced the public innovation narrative and criticized Telenor for not providing sufficient support to the Norwegian industry, as Telia had done in Sweden.

The international telecom literature emphasized relationships between operators and equipment suppliers,Footnote 22 yet these relations were also criticized for being cozy market arrangements.Footnote 23 The Telia-Ericsson narrative stands out as mainly positive both by international scholarsFootnote 24 and certainly by Swedish scholars.Footnote 25 It was, allegedly, not a cozy relationship because Telia produced a substantial part of its own equipment, and Ericsson did not have a captive market in Sweden. Mats Fridlund has described “the long-term user-producer relation that, since the 1920s, had developed between” Ericsson and Telia.Footnote 26 This relationship was strengthened in 1969 at a lunch when Telia’s and Ericsson’s chief executive officers met with Marcus Wallenberg, who was the largest owner in Ericsson. The CEOs wanted to discuss the establishment of a joint venture, Ellemtel, to develop a digital switch. This “lunch story” is told many times to explain Sweden’s leading role in the telecom sector,Footnote 27 most recently in a 2015 public report on digitalization from the Swedish government.Footnote 28 The Telia-Ericsson narrative is a classic integration of historical genesis and retrospection, with roots that start in the 1920s that explain Ericsson’s success in the 1990s.Footnote 29

The Telia-Ericsson story, which originated with public procurement, is one of many such buyer-supplier relationships in Sweden.Footnote 30 Fridlund’s publications in support of the Telia-Ericsson narrative is based on the following. Ellemtel produced a digital switch that allowed Ericsson to sell it on export markets and for Telia “to have one single system for the whole country.”Footnote 31 It provided Sweden with one of the best networks in the world, so the technological partnership benefited both parties and the country. These points were confirmed by other Swedish scholars.Footnote 32 Ericsson has also actively promoted the Telia-Ericsson narrative.Footnote 33 For example, for Ericsson’s centennial anniversary history in 1976, the Telia-Ericsson relationship was given much attention, and the joint venture of Ellemtel was described as “unique in the world.”Footnote 34 On Telia’s website, too, Ellemtel is characterized as “a gigantic success both in Sweden and worldwide.”Footnote 35

This narrative was coupled to larger Swedish national narratives of science and progress,Footnote 36 and it had other positive dimensions, such as stakeholdership, trust, and cooperation.Footnote 37 Lindmark et al. commented that “geographic proximity promotes the repeated interaction and mutual trust needed to sustain collaboration.”Footnote 38 In doing so, they echo other acclaimed Swedish scholars.Footnote 39 Thus, in praising the Telia-Ericsson relationship, the literature became part of the broader public innovation and collaborative narratives.Footnote 40 This can be seen in the various post-Fordist and postindustrial narratives or discourses from the 1960s.Footnote 41 Some of these narratives gained pace in the late 1970s in reaction to evolving political liberalization.Footnote 42 Moreover, some “re-emerged strongly in the early 1990s.”Footnote 43 The latter is when Fridlund’s publications pushed the Telia-Ericsson narrative, which should be considered in relation with the growing prevalence of the systems of innovation approach at the time.Footnote 44

The collaborative narrative advocated a movement away from Oliver Williamson’s transaction cost theory—with its emphasis on self-interest, opportunism, arm’s length and adversarial relationsFootnote 45—and toward long-term relationships based on collaboration, trust, and sharing information.Footnote 46 Attempts to pit suppliers against each other in tenders was considered counter-productive, and Villena et al. note that “the literature […] is unequivocal regarding the value of collaborative buyer-supplier relationships.”Footnote 47 Stories of the collaborative narrative are particularly strong in Swedish academia,Footnote 48 in research on marketing, international business, and innovation.Footnote 49

The public innovation narrative and collaborative narrative had strong support in Norway as well, which is evident in both the literature on Telenor and on the politicized petroleum industry.Footnote 50 Nevertheless, in Norway these narratives never escaped a liberal and economistic skepticism.Footnote 51 Maybe because the country was more influenced by the school of Adam Smith than was Sweden.Footnote 52 Additionally, Oliver Williamson has had a much stronger impact on Norwegian business studies than on Swedish ones.Footnote 53 This accords with that the Swedish economy was geared more toward manufacturing and innovation than transactions.Footnote 54 Multinationals like Ericsson, ASEA/ABB, Electrolux, Aztra (Zeneca), and Volvo fueled Swedish national pride and confidence.Footnote 55 Norway, on the other hand, was marked by its cash flow-oriented businesses, like shipping, and in harvesting its natural resources.Footnote 56 The Norwegian mindset was to exploit comparative advantages for exports and to import technology-intensive products, often from Sweden.Footnote 57

The innovations resulting from public procurement and buyer-supplier relations in Sweden are impressive, as is much of the research on these relations and innovations. Still, it is noteworthy that so few Swedish scholars have addressed this from the perspective of power and interests, not least because most companies that benefited from public procurement was part of the powerful Wallenberg sphere.Footnote 58 The Telia-Ericsson relationship, and other collaborative relationships, have been presented as the result of smart design and a rational and functional economy,Footnote 59 not of economic interest and power. The national dimension of Sweden’s industrial policies became more apparent to Norwegians, as it was a host country to many technology-intensive Swedish multinationals.Footnote 60 With this as a background, the article now turns to Telenor’s relationship with its equipment supplier in the twentieth century.

From Procuring Power to High Transaction Costs

The telecom sector was consolidated during the first decades of the twentieth century when European PTOs first monopolized operations of long-distance networks that linked with private networks, which they then eventually absorbed. The arrival of automatic switches further consolidated the industry.Footnote 61

Elektrisk Bureau (EB), a Norwegian manufacturer of telecom equipment, tried to develop an automatic switch, but without success.Footnote 62 It did not receive any support from Telenor or the government, and EB’s demands for increasing tariffs were not heeded. Norway’s cabinet “rejected [higher tariffs] because these products ought to be ‘as cheap as possible’ in consideration of ‘our nation’s communication system.’”Footnote 63 Ericsson took over control of EB in 1928.Footnote 64

As the PTOs gained monopolies, they became monopsonists of telecom equipment. When installing automatic switches in Oslo in the 1920s, Telenor exploited its power by pitting suppliers against each other in tenders. It selected a switch made by Western Electric, which established a subsidiary in Norway that later became Standard Telefon og Kabelfabrik (STK), the Norwegian subsidiary of International Telegraph and Telephone (ITT).

ITT/STK and Ericsson/EB signed an agreement in 1934 that divided the Norwegian market between the two companies, which undermined Telenor’s ability to arrange tenders.Footnote 65 It should be noted that similar agreements appeared throughout Europe before 1940.Footnote 66 This was due to rising transaction costs caused by specificity and information asymmetry.Footnote 67 There were particularly three interrelated factors that increased the transactional costs and allowed the equipment supplier to make market agreements. First, switching equipment lacked common interfaces, so it was difficult and/or expensive for equipment from different suppliers to interact. At least this was claimed by the suppliers, which points to the second factor: Telenor lacked sufficient competence in the field and was vulnerable to the suppliers’ opportunism. While the first-generation automatic switches were discussed at international conferences, generating knowledge for PTOs, switching “disappeared entirely from international meetings” from 1922 onward.Footnote 68 Third, PTOs, including Telenor, thus became reliant on suppliers for repair, maintenance, and upgrading of switches. Two additional factors were related to the telecom industry being part of the political economy, or “negotiated environment.”Footnote 69 When procuring equipment, Telenor was expected to take stakeholder considerations into account and to appreciate externalities seen as positive for society. One factor was the interests of ITT/STK and Ericsson/EB workers, and another factor was to support the technological and industrial developments in Norway that were in line with the public innovation narrative. Together, these five factors allowed the industry to have an oligopolistic grip on Telenor.Footnote 70

Telenor’s reputation declined in the postwar period when the Labor government did not prioritize telecoms in its allocation of scarce resources; the telephone was instead regarded as “a noble need.”Footnote 71 The result was queues of people waiting to have a telephone installed in their homes, a problem that haunted Telenor into the 1980s. It was little comfort that Norway shared this problem with other European nations.Footnote 72

Telenor hoped to solve some of its problems by importing modern equipment. It was persuaded to be the first procurer of an electro-mechanical switch in the 1950s, produced by Bell Telephone Manufacturing (BTM), ITT’s Belgian subsidiary. The switch was called 8B, and Telenor was enticed by its alleged futuristic high tech features, which indicates Norway’s inclination to import technology-intensive products. The purchase backfired when no other PTO bought the switch, making Telenor the only user.

Fixing problems with the 8B, and other switches, required craft-like skills, including tacit knowledge, which were difficult to codify and standardize. STK and EB would often fix issues with some homemade solutions.Footnote 73 In an internal Telenor document, the network was referred to as “a true weed flora of equipment variants.”Footnote 74 These problems increased transaction costs, and Telenor did not know if it was a victim of opportunism by its equipment suppliers.Footnote 75

Telenor’s relationship to its suppliers was maybe the worst of all options: an arm’s length relationship with high transaction costs and strong stakeholder responsibilities. If a transaction costs analysis had been conducted, it would probably have found that Telenor should have internalized its manufacturing; that is, made its own equipment. It did consider minor production in 1946, inspired by Telia, which allegedly benefited from producing much of its own equipment.Footnote 76 However, nothing came out of the considerations. In the 1960s, the Ministry of Industry said it was content to depend on foreign firms in telecom “since we do not have specific advantages” in this field.Footnote 77 This affirms the notion that Norway was content to import technology-intensive products.

The Research Revolution

Telia remained an important reference for Telenor, and it was assessed that the Swedish PTO’s costs for equipment was half of what Telenor paid.Footnote 78 A Telenor engineer visited Telia in Stockholm for some months in 1958 and came back full of praise, not least because of the research and development (R&D) Telia conducted.Footnote 79 During the 1960s, the public innovation narrative gained ground in Europe as nations emulated the American policy of increased public funding for R&D.Footnote 80 In this decade in Norway, the government’s funding of technical-industrial R&D increased six-fold.Footnote 81 The rapid developments in information and communication technologies (ICT) promoted the public innovation narrative.Footnote 82 The Norwegian strategy of “research driven industrialisation” in the 1960s was mainly aimed at ICT.Footnote 83

In Norway, the debate about the government’s role in innovation was shaped by a harsh critique of Telenor and, in particular, its procurement of radiolink (microwave) equipment from ITT through STK.Footnote 84 Meanwhile, the government refused to buy similar equipment from the Norwegian company Nera, because it distrusted the company’s capacity to deliver. Nera had developed radiolink with the National Defense Research Establishment for the armed forces. Several people engaged in military communication were critical, bordering on hostile, against Telenor. Bjørn Rørholt, head of the Norwegian Defense Communications Administration, and an influential colonel, was photographed standing on his head, claiming he wanted to see the world from Telenor’s point of view.Footnote 85

The problems with Telenor reached the cabinet, which established the Committee for Electronics to “present propositions […] to stimulate the development of the electronics industry in Norway.”Footnote 86 The committee published a report that was critical of Telenor while lauding Telia for its R&D and its “intimate relation with the domestic industry.”Footnote 87 In response, Telenor created a research institute, Televerkets Forskningsinstitutt (TF), in 1967. Even TF’s employees did not hold Telenor in high regard. Ole Petter Håkonsen, who worked at TF before he, ironically, became technical director at Telenor, said that in the 1960s “only jerks would start to work at Telenor.”Footnote 88 Moreover, the institute was located quite a distance from Telenor to avoid being entangled in its everyday work. Thus, the institute was kept estranged from Telenor’s internal workings.Footnote 89

One goal of TF was to stimulate Norwegian companies via development contracts. Other goals were to get access to ITT’s and Ericsson’s knowledge pool and to help STK and EB “win the internal competition in the multinational among the subsidiaries. Thus, resources and mandate could be allocated to Norway with possibilities for export.”Footnote 90 TF had a fruitful development contract with STK on pulse code modulation (PCM), not least because other ITT subsidiaries were sharing knowledge with TF and Telenor.Footnote 91 STK experienced successful industrial development because of a PCM contract and other contracts with the National Defense Research Establishment.Footnote 92

EB also received many contracts from TF, but little came out of them. Telenor thought Ericsson was difficult to work with, as they were reluctant to share knowledge. Moreover, they kept a tight control over EB.Footnote 93 For example, Ericsson’s CEO told EB’s managing director that EB’s main task was to supply Telenor with Ericsson’s telecom equipment, and its “second large task—but after its main task—was to develop its own products.”Footnote 94 Nera and other Norwegian companies received more support and development contracts from TF and other government bodies, but still not much happened.Footnote 95 In 1976 the government requested that EB take over Nera to rescue the company, as part of this operation, Ericsson agreed to reduce its ownership in EB so Norwegians would hold the majority of EB’s shares. The Wallenbergs hoped this would improve EB’s standing in Norway. It should be noted that these operations were managed by the Ministry of Industry, and that Telenor was not involved.Footnote 96

The Nordic Mobile Telephone (NMT) system was the most important outcome of the Norwegian R&D efforts within ICT in the 1970s, and it was a result of cooperation among Nordic PTOs starting in 1969.Footnote 97 NMT was a platform for the next generation of system—namely, the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM)—which was developed in the 1980s and 1990s, and in this Telenor played a leading role. This article does not question the significance of the Nordic PTOs on creating NMT and GSM, or in forwarding Nokia’s, Ericsson’s, and Telenor’s successes. This is a discussion beyond the scope of this article and is covered in other publications. As McKelvey et al. write, “The history of mobile telecommunication in Sweden is to a large extent the history of the firm Ericsson and its relationship to the Swedish PTTs.”Footnote 98 However, given the great public effort, there was very little industrial development in the Norwegian telecom industry,Footnote 99 and especially with mobile telephony. A senior researcher from Telenor said that this lack of development was the “the largest disappointment that has been seen in the history of Telenor R&D.”Footnote 100 For Telenor, the public innovation narrative lost much of its pull, which allowed it to modernize its network in the 1970s.

From High Transaction Costs to Procuring Power

Telenor’s transaction costs fell in the 1970s, one reason being its increased knowledge. The PTO improved its planning and control for the whole network in relation to the growth in long-distance and international calls, and it completed automation of its network. The system required specifications for signaling, billing, transmission, and directing, which in turn required cooperation with international bodies.Footnote 101 These bodies became important sources of further information and knowledge. After being absent for decades, switching reappeared in international forums in the 1960s.Footnote 102 There were also fruitful interactions between research and internationalization.Footnote 103 TF was important in these activities, although its role in switching is disputed, as its approach was considered too theoretical and its relationship with Telenor’s switching department was strained.Footnote 104 Additionally, starting in the 1960s, larger numbers of students were graduating with degrees in electronics and computing, which provided Telenor with more and better candidates.Footnote 105

Unfortunate developments at STK were also critical to the changing buyer-supplier relations. The above mentioned 8B switch created problems for Telenor, which STK struggled to fix.Footnote 106 Moreover, in the late 1960s, ITT convinced STK to take over a project with a rural switch. STK was enthusiastic about this work and invited Telenor to take an active part in “one of the largest development projects in telecommunication in the country.”Footnote 107 Telenor welcomed this opportunity, but was not carried away; it wanted a product, not a project.Footnote 108 Ultimately, the rural switch project was a disaster for STK because of delays and increased costs;Footnote 109 and as with 8B, Telenor was the only user. Even though the rural switch was far more expensive than other alternatives, Telenor bought a considerable number of them. STK was hit hard by other problems, but Telenor needed STK for repair and maintenance of the switches.Footnote 110

The Norwegian Auditor General had more impact in the late 1960s, and the office took particular interest in Telenor’s procuring methods.Footnote 111 Starting in the early 1970s, it ordered Telenor to use tenders when possible. In areas where interfaces impeded tenders, it required the PTO to use cost contracts and to inspect suppliers’ books. Equipment suppliers, of course, tried to avoid these inspections. They showed that STK’s price for the 8B was high, but fair, and accurately reflected STK’s costs. EB, however, was severely criticized for setting the price “much higher than costs and a reasonable profit implied,” and it was ordered to lower the price of the switch by 40 percent.Footnote 112 EB’s and Ericsson’s standing was harmed when this opportunistic behavior was exposed. Meanwhile, STK’s reputation suffered from its inferior and expensive products. Both of these events furthered Telenor’s distrust of the Norwegian subsidiaries.

Telenor concluded that it needed to be much tougher on its suppliers. It also needed to invest in future technology, including computerized switches, also known as Stored Program Control (SPC) switches, with “an urgent need” to acquire “better competence and insight in [these] switches.”Footnote 113 Telenor sent engineers to Ericsson in Stockholm and BTM in Antwerp to study SPC switches. The computerized switches did not have the same trouble with interfaces, so Telenor requested that STK and EB submit offers for two tenders in 1971.Footnote 114 The equipment suppliers were informed that Telenor would disregard the market agreement from 1934 and consider only price and quality. The agreement was actually broken when EB/Ericsson won a contract in Oslo, STK’s home market. The head of STK’s telecom business was furious with Telenor, arguing in a meeting that the contract was a result of Telenor’s incompetence.Footnote 115 He tried to reinstate the company’s oligopolistic control by claiming that Telenor neglected its stakeholder responsibilities toward STK’s workers.

Still, BTM and STK won a contract for a local SPC switch in Oslo, and BTM invited Telenor to send personnel to Antwerp. Several Telenor engineers worked at BTM in the mid-1970s, with some staying as long as eighteen months. A key task was to program relevant features of the Oslo network into the SPC switch’s software, forcing Telenor to systematize and register all general and specific traits and features of the network. The specifications for signaling, billing, transmission, and directing had to be worked out for the local networks’ mechanical switches, and handwritten schemes had to be programmed into the SPC switches.Footnote 116

Buyer-supplier relations are often presented as either having a pure market or an interactive approach.Footnote 117 This is too simplistic, because many relations entail interaction. Thus, the question is the nature of those interactive relations. Is it mainly collaborative and trusting, or mainly arm’s length and framed by formalized contracts? Telenor’s relationship with BTM was the latter. The involved parties praised the good working relations, but BTM felt Telenor’s contracts were very demanding, including both strict specifications and time limits. One BTM employee said this “was unheard of in the business in the 1970s.” This action made Telenor a frontrunner in this style of business. According to another BTM interviewee, Telenor was becoming the most professional and demanding PTO in Europe.Footnote 118 BTM was very pleased with its relations with Telenor; an important factor was probably that it did not have to pay any fines for delays. STK was Telenor’s contractual partner, and thus it had to paid all the fines to Telenor related to delays on the SPC project.Footnote 119

Telenor demanded all features for the SPC switches, including automatic redirection, wake-up calls, and speed dialing.Footnote 120 This required additional programming and increased memory on the computer of the SPC switches. BTM was more than happy to further develop its SPC switches with the Norwegian PTO. At the same time, in the mid-1970s, Telenor was struggling with its bad public image. The network in Oslo occasionally broke down because of old equipment. The Norwegian public, living with these problems, had no idea that Telenor was considered a “professional and demanding PTO.” The same goes for key people in STK, EB, and TF; they either did not know of or appreciate Telenor’s new gained knowledge.Footnote 121 Telenor realized that no matter how much effort was put into these old switches, they would never work well.Footnote 122 It would only be wasting money, and thus it would be better to allocate resources and efforts on future equipment and new relationships.

Digitalization and Liberalization

While installing the SPC switches, Telenor was also developing a strategy on digital switches: how and when to procure and install them. Companies like Ericsson and ITT, as well as newcomers like Nokia and Alcatel, were developing their own digital switches.Footnote 123 Telenor considered a Norwegian digital switch, but “the Norwegian market [was considered] too small,” and the PTO had “few good experiences with maintenance and upgrading of special Norwegian types.”Footnote 124 In 1990, Telenor’s director of communications claimed publicly that the development costs of digital switches were so high that “no one in their right mind” could mean that Norway should try to do this.Footnote 125

Digital switches could be programmed to interact with other switches, meaning idiosyncratic interfaces were no longer obstacles in arranging tenders. This provided the PTOs with power, which some used to make demands toward the equipment suppliers. When the Australian PTO procured a digital switch from Ericsson, it demanded R&D activity from the Australian subsidiary of the Swedish multinational.Footnote 126 French authorities nationalized the French subsidiaries of ITT and Ericsson.Footnote 127 Telenor invited STK and EB to a series of meetings in 1980 and 1981 on the pretext that it was a “now or never” chance to change the Norwegian telecom industry.Footnote 128 Telenor proposed a merger between STK and EB: a united company could have licensing agreements with Ericsson and/or ITT. The initiative came from Telenor’s top management, but there is little reason to believe that Telenor’s technical or switching departments supported the initiative. Nevertheless, Telenor asked the subsidiaries to come up with ideas for future business opportunities, but STK and EB refused.Footnote 129 Telenor realized the subsidiaries were more loyal to their mother companies than to the Norwegian stakeholders.Footnote 130 As a consequence, Telenor felt relieved of any stakeholder obligation. For Telenor, digitalization led to liberalization.

It is worth remembering that Telenor still struggled with a bad public image, and few had confidence it would manage the transition to digital technology. This concern prompted the establishment of the National Telecommission in 1981. The head of TF was a prominent member of this commission, but he stated that he only represented himself, not Telenor, and, this was understood as he shared the general negative impression of Telenor. Another illuminating story is that a Telenor employee fell off his bike on the way to the commission’s first meeting. He looked bloody and beaten up. When he arrived, he said, “You all understand where I come from!,” suggesting that he had been beaten up by angry telephone subscribers.Footnote 131 Nevertheless, and despite general skepticism, Telenor’s board and management had confidence in the PTO’s switching department.

Telenor arranged a tender in 1982 to install digital switches for half of the Norwegian network, which was considered the “contract of the century.” Other international suppliers were invited to participate, in addition to STK and EB. STK presumed that EB would win because of its increased Norwegian ownership, so STK asked Telenor to consider its stakeholder responsibilities and thus buy from both STK and EB. Telenor rejected such responsibilities, and it made it clear to STK, the public, and all the involved parties that it would consider only price and quality in the offer.Footnote 132 Liberal politicians and business magazines welcomed that STK and EB had to compete. They were characterized “as two laidback ‘fat cats’ who had lain beside each other and produced some of the most expensive tele-products in the world.”Footnote 133 Telenor did not indulge in such attacks either publicly or privately, but only talked about price, quality, and how the selected switches would improve the network and thus services to their customers.

BTM convinced ITT to use Telenor as a showcase for its digital switch, as “all the other PTOs looked to Norway.”Footnote 134 STK was told to dump the price and was promised that ITT would cover any losses. The STK price offer was allegedly 40 percent lower than EB’s offer, and that was the deciding factor for Telenor to choose ITT’s/STK’s switch in 1983. The loss came as a shock to both Ericsson and EB.Footnote 135 There was some schadenfreude in Telenor that the “Big Swede” lost, yet the sources are clear that only price and quality mattered in the decision making. There was a sense of pride at Telenor that the company had become a demanding procurer. Telenor employees reveled in solving problems and working out specifications.

The installation of the first ITT/STK switches was delayed due to difficulties with programming. This again fueled the public’s opinion that Telenor was not capable. The negative evaluation Telenor received in 1985 in the Nordic comparison—that it “had no vision for the technological development that took place”—was reflective of the general attitude at the time.Footnote 136 Nevertheless, despite initial delays, the installation was a success for Telenor and ITT. It allowed ITT to divest its telecom business to Alcatel.Footnote 137 ITT’s switch and Telenor’s solutions were showcased internationally. Delegations came from South Korea, Australia, the Netherlands, Spain, China, Italy, Belgium, and Switzerland, and some of these countries “bought Telenor’s specifications.”Footnote 138 Telenor was satisfied with the switch and the cooperative relationship with BTM, but it was disappointed with STK’s contribution.Footnote 139 It proved to be a Pyrrhic victory for STK, which incurred heavy financial losses from the delays and resulting fines, and then ITT did not stand by its promise to cover STK’s losses.Footnote 140 STK hoped it would regain some of these losses when the digital switches were installed across the rest of the network.

Telenor issued a second tender in 1990 to complete the digitalization of the network. STK promised more production in Norway if it won the contract, but Telenor was not interested in such aspects. It was eager, however, to convince Ericsson that it was open to operating two systems, and that, again, only price and quality would count in decision making. Ericsson dumped the price, as it felt compelled to win in Norway. Telenor concluded “that Ericsson had defined a totally new price level with the offer.”Footnote 141 Word was that Telenor paid half of what Telia did for the same equipment.Footnote 142 Telenor wanted two systems, as this laid the foundation “for a real competition also at the next tender round.”Footnote 143 Telenor even added an extra monopoly tariff on STK’s prices because it was certain that STK would exploit an eventual monopoly in the future.Footnote 144

The two tenders provided Telenor with a top quality network at a very good price, yet Telenor never created a narrative about its success. This is most likely why so few people know of this process. A telling example is when the Norwegian Minister of Communication said in 2002: “It may sound weird today, but the National Telecommission actually found it pertinent to recommend [Telenor] a strategy for replacing outdated equipment and implement new technology, as if that was not a matter of course.”Footnote 145 This was very far from the truth.

Digitalization, Liberalization, and Globalization

Mats Fridlund presented his work on the Telia-Ericsson relation at a seminar in 1996. Ole Petter Håkonsen, who was Telenor’s technical director at the time and a key figure in Telenor’s digitalization strategy in the 1980s, was present, and commented on Fridlund’s talk. Håkonsen explained that he was relieved that Telenor was not caught up in a similar relation like Telia-Ericsson.Footnote 146 He maintains that Telenor wanted equipment “according to [our] open, international specification and interfaces, at competitive prices.” Moreover, he says that Telenor “would at any cost avoid being dependent on one supplier [ . . .] which would limit our freedom to choose in the future.”Footnote 147 This was contrary to the normative message of the Telia-Ericsson collaborative narrative.

Håkonsen said the digital switch’s success allowed the PTO to feel confident, which was new for Telenor. Their installation provided Norway with “one of the most modern and digitized (networks) in Europe.”Footnote 148 In the 1990s, Telenor was eager to talk about the enormous savings and improvements the network provided. It boasted that Norwegians had among the lowest prices for telecom services in Europe.Footnote 149 The general opinion of Telenor rose in the general public.Footnote 150 If anything, Telenor might have had too much confidence. “We were so satisfied with ourselves,” one employee said, “that the only thing we lacked was the Lord’s official blessing.”Footnote 151

The contrast to the Swedish story is marked. Lindmark and colleagues said that in the new telecom regime, the “locus of influence changed from operators to suppliers.”Footnote 152 In Norway, it was the opposite. STK and EB more or less fell apart as companies in the 1990s, and other Norwegian IT companies shut down. This benefited Telenor because it could cherry-pick the best employees from these companies.

In 1990, Telenor had about 2.2 million subscribers on fixed lines in Norway.Footnote 153 These numbers expanded through foreign direct investment in Eastern Europe in the 1990s, so that by 2000 it had 15 million customers.Footnote 154 The main ownership advantages were superior knowledge of the GSM system and an ability to roll out mobile networks efficiently.Footnote 155 The foreign direct investments were financed by revenues from the Norwegian network, which accounted for the bulk of Telenor’s revenues in the 1990s.Footnote 156 This, again, was possible because of the high quality and low price Telenor attained through its tenders in 1982 and 1990.

European PTOs were key actors in the public innovation narrative in conducting and financing R&D. Martin Fransman notes that in the new telecom regime, a “new breed of operators emerged, flexible and with little or no R&D since technology could be readily supplied by the manufacturers.”Footnote 157 To compete with the new entrants, the former PTOs scaled down their research, as had Telenor.Footnote 158 Moreover, as the equipment became standardized off-the-shelf products, technology and equipment became necessary but not sufficient conditions for a company to succeed.Footnote 159 Jon Fredrik Baksaas, Telenor’s former CEO (2002–2015), said in a public lecture in 2015 that “the technology advantage in telecommunications hardly exists. Mobile operators are using more or less the same equipment all over the world.”Footnote 160 The former technology director in Telenor, Berit Svendsen, said in an interview, “Telenor should not do basic research.”Footnote 161 What was needed was knowledge on how to build a network and how to increase its capacity. “The most important thing is to be able to use others’ ideas and commercialize them successfully.”Footnote 162 Thus, Telenor focused more on marketing and services while Telia was rooted in the physical network.Footnote 163 The difference between Telia and Telenor became apparent in 1999.

Telenor and Telia merged in 1999, but it was cancelled almost immediately when the parties failed to agree on the location of the headquarters for mobile telephony. Given that it was the company’s best interests that should determine the location, most Swedes presumed that meant Stockholm, which was home to Kista, a global center for telecom and mobile telephony. The Telia-Ericsson narrative was again activated and applauded in the media.Footnote 164 However, Håkonsen and other Norwegians did not want the merged company to have a special relationship with Ericsson, as they thought this had impeded Telia’s development.Footnote 165 Swedish commentators mocked this argument as an expression of Norwegian nationalism and feelings of inferiority.Footnote 166 There were rumors that Ericsson simply would not accept headquarters in Norway.Footnote 167 The low point occurred when the Swedish Ministry of Industry said that Norwegians “are so incredibly nationalistic.”Footnote 168

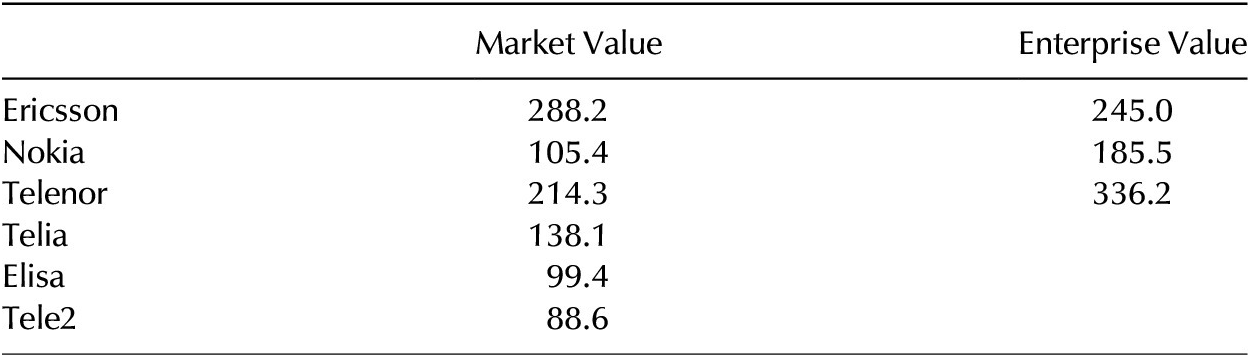

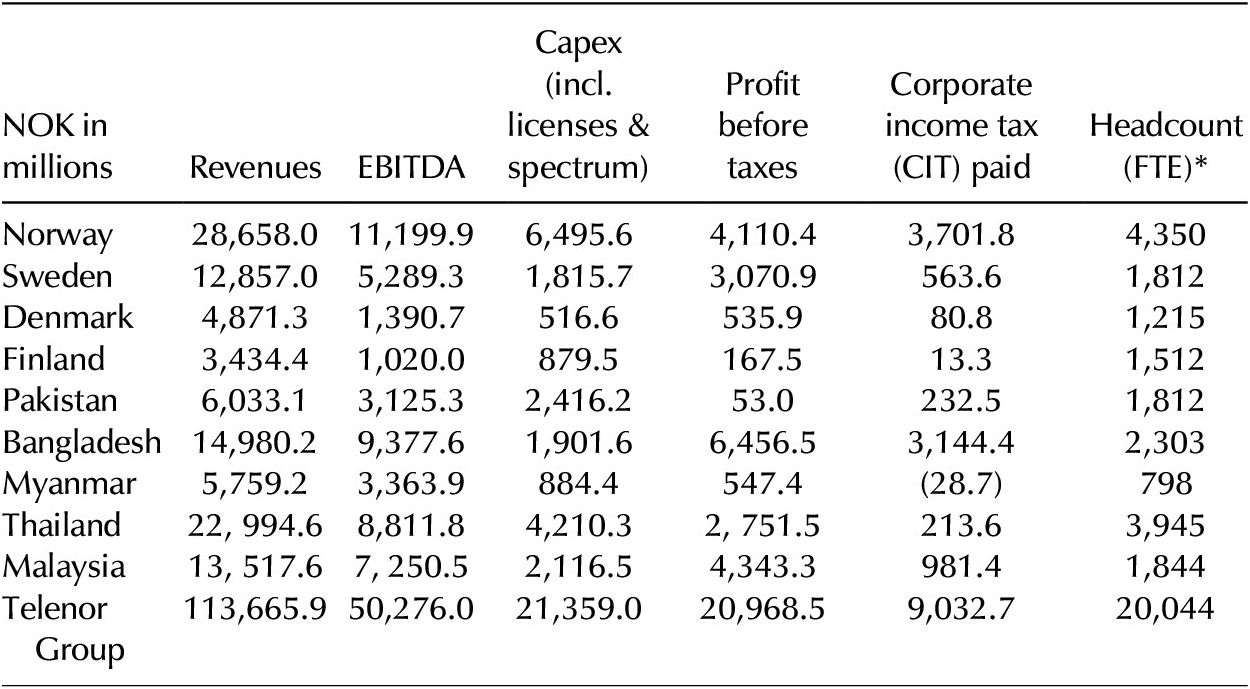

Telia was believed to be almost twice as valuable as Telenor in 1999. In the Telenor/Telia merger agreement, the ownership split was 60/40 in Telia’s favor, and Telenor was considered lucky to get that ratio.Footnote 169 Telia became even more valuable after it merged with the Finnish operator Sonera in 2002. Now, however, Telenor has a larger business operations (Table 1), and Telia is worth only two-thirds of Telenor (Table 2). In 2019, an analyst estimated that Telia’s shares had increased by 24 percent, adjusted for dividends, over the preceding twenty years. During the same time period, Telenor’s shares increased by over 850 percent.Footnote 170 An important reason is that Telenor was a shrewd dealmaker, making a profit of NOK 21 billion in 2001 by exercising two put-options: Telenor sold its shares in the German Viag Interkom and in the Irish East Digifone, to British Telecom, at a prearranged price after the dot-com had burst.Footnote 171 The most important reason, however, is that Telenor turned mobile telephony into a mass market in many Asian countries(Table 3).Footnote 172 The number of its customers increased to 186 million by 2019.Footnote 173 Ericsson and Telenor are currently the largest telecom companies in Scandinavia (see Table 2).

Table 1 Key financial figures for Telenor and Telia, 2019

Source: Based on Telenor, Telenor Annual Report 2019; https://www.telenor.com/investors/annual-report-2019/; Telia, Telia’s Annual Report 2019, https://www.teliacompany.com/globalassets/telia-company/documents/reports/2019/telia-company--annual-and-sustainability-report-2019.pdf

Table 2 Largest telecom companies in Scandinavia, billions NOK

Note: Enterprise value is market capitalization plus debt. The debt to enterprise value is derived from annual reports. Market value is from May 7, 2020.

Source: Computations from an analyst at DnB ASA (using Bloomberg.com); e-mail to author, May 7, 2020, in author’s possession.

Table 3 Telenor’s country-by-country reporting, financial year 2019

Note: FTE = full-time employees, as of December 31, 2019.

Source: Telenor, Annual Report 2019 (https://www.telenor.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/2201011-Annual-Report-2019-Q-a97d1b270234873cebe5901dfe14e8c2-1.pdf).

Telenor is the first Norwegian company to succeed on a global scale in a consumer market. Despite its success, there is no dominant public narrative or captivating corporate narrative about Telenor’s development over the last thirty years. Telenor has struggled to come across with a captivating corporate narrative. It has tried to accentuate that mobile communication empowers poor people in Asia. Still, the emphasis by the media and commentators is often on the successful transformation from an old bureaucratic institution to a profitable multinational company.Footnote 174

Telenor has delivered impressive value to its shareholders, of which the Norwegian government is the largest. However, shareholder value alone does not appeal to a greater purpose, which is necessary in creating engaging narratives. One hurdle is that there are few positive externalities from Telenor’s business in Norway, except for financial returns and greater value for the business community.Footnote 175 This means there is limited foundation for impression management. This may be at heart of Telenor’s troubles related to others writing its history. Telenor commissioned a history book for its sesquicentennial anniversary in 2005, but was allegedly reluctant to publish the last volume, which covered the modern era. The author, Lars Thue, was critical of the fact that revenues from the Norwegian network subsidized Telenor’s foreign investments, and that Telenor had scaled down its R&D to prioritize shareholder value.Footnote 176 Telenor commissioned another book, but it halted the work in 2019 for reasons never made public.Footnote 177

Time and again, Telenor has been criticized for cutting back on research,Footnote 178 which is a testimony to the enduring strength of the public innovation narrative. This constant critique has exhausted senior Telenor managers. For example, at a closed seminar in 2017, Jon Fredrik Baksaas was asked why Telenor had reduced its research activities. He sounded fed up when he responded: “Yes, we could have continued to research ourselves to death, or we could go abroad and make money. We did the latter.”Footnote 179

Conclusion

This conclusion will return to the initial research questions. First, why did Telenor choose an arm’s length relationship with its equipment supplier starting in the 1970s? Second, why has the Telia-Ericsson narrative remained so prevalent, even after it seemed anachronistic? Finally, why has this story of Telenor not been told?

In the postwar years, Telenor was criticized for neither cooperating with nor supporting the telecom industry. This critique was based on the public innovation, collaborative, and Telia-Ericsson narratives. Telenor rejected the critiques and the narratives from the 1970s, asserting that it would have limited its freedom to choose the best equipment in terms of price and quality. Telenor was a pioneer in using tenders and strict legal contracts with suppliers. Its historical experience is important in explaining its strategy. First, it had little reason to be inspired by the public innovation narrative. Despite continuous efforts from different government bodies, the Norwegian telecom and IT industries had proved unable to develop themselves. Second, the memory of specific interfaces that limited Telenor’s choice left a strong mark, and key actors were exceedingly careful to avoid a similar situation in the future. Finally, Telenor’s history provides little resonance for the collaborative narrative. Telenor’s leadership did not have to read Oliver Williamson to be familiar with opportunism and “self-interest with guile”; they learned it firsthand from the equipment suppliers.Footnote 180

Although Telenor’s procurement strategy in the 1970s was based on its historical experience, the PTO had shown an early preference for using tenders and importing technology. This accords with the notion that the Norwegians lacked confidence and tradition in making technology-intensive products, and contributes to our understanding of why Telenor embraced a new regime based on sourcing and procuring technology on an arm’s length basis.

The liberalization that swept over Western countries in the late 1970s reduced stakeholder obligations across several industries, resulting in the increased use of tenders and arm’s length contracts in buyer-supplier relations, not only in the telecom but also in a number of other industries.Footnote 181 It is a paradox that when digitalization, liberalization, and globalization transformed much of Norwegian and international buyer-supplier relations, the public innovation and collaborative narratives grew stronger, not least the Telia-Ericsson narrative.

One explanation is that the Telia-Ericsson narrative was merely an account of the past, although publications also highlight policy implications. A more plausible explanation is that it was in line with the growth of other post-Fordist and postindustrial narratives in the 1990s, and many scholars were opposed to liberalization. The Telia-Ericsson narrative included positive features, or aesthetics qualities, such as trust, cooperation, and innovation; and it was a key component in a larger national industrial narrative in Sweden that emphasized trusting and collaborative relationships. Without pointing at any causality, it is also relevant that the narrative served powerful interests, such as Ericsson and the Wallenbergs.

Finally, this narrative was promoted by numerous Swedish scholars. It is obvious that Ericsson benefited from the cozy relationship, but did Telia and Sweden? There are three propositions that suggest the answer is yes. First, Sweden benefited by gaining a world-class telecom network; and second, Telia benefited from having only one type of switch in its network. Third, Telia benefited in general from its close relations with Ericsson. It is difficult to validate these assertions. The fact that Telenor chose a different strategy, with considerable more success, does not support these propositions.

The point I make here, however, is not whether these propositions are valid but why Swedish scholars do not question them. Historians and other scholars should always bring a Popperian approach to their analysis by trying to falsify critical assumptions and propositions. This is especially important when their research feeds into a strategic narrative. Business historians should keep investigating the validity of narratives and their implications, and this does not have to be at the expense of researching the “narratives’ origins and effects.”Footnote 182

Finally, this story has remained in the dark, as Telenor did not create a narrative to legitimate its strategy in dealing with equipment suppliers. It could have incorporated several elements from its own history or from the emerging liberalization, but it did not. Telenor remained focused only on price and quality, facts and data, and being apolitical in its decision making. When asked about the importance of narratives, feelings, or animosity toward the “Big Swede,” interviewees from Telenor deny any of that had an impact on their work. They were much keener to talk about how efficient the network had become.

Telenor’s “rationality” could be perceived as a narrative in itself, in that it functions as a model that reduces complexity and provides sense making. It also bestows legitimacy to the strategy, both the process and the result, of using the tenders. Still, it has never been presented as a story. Maybe business history has been too focused on reductionism and instrumental rationality in general, but it seem apposite in this story. Telenor was eager to convince equipment suppliers, as well as others, that there were no greater purpose to their relationships or procurement style other than getting the best deal in terms of price and quality. The Telia-Ericsson narrative, with its aesthetic qualities, trust, wider stakeholder interests, and assumed positive externalities, was rejected by Telenor because it would limit their decision making as related to procurement. Telenor’s strategy was to be fact-based, transparent, and fair. Future research should look deeper into the role of narratives and culture of companies that pursue market-conforming strategies. This picks up on Lipartito’s challenge: “Locating culture in what we have assumed to be non-cultural.”Footnote 183

Telenor did not use any narrative to promote its successful strategy in the 1970s and 1980s, but why has the company not promoted this history, and why have others, including researchers and commentators, not picked up this story? One reason is that the nature of buyer-supplier relations became less important after the 1980s. Their own equipment and technology were not deemed essential for Telenor’s success. Given that buyer-supplier relations and technology is now perceived as less important, maybe this has little to offer Telenor’s present business challenges. Finally, this story is related to the disappearance of STK and EB; while this is not problem for those familiar with the need for creative destruction, it is hardly a good selling point. Still, the history of Telenor’s buyer-supplier relationship has one quality that could be brought forward; namely, that it offers a connection and transition between Telenor’s troublesome past and its successful present. The past difficulties are what motivated the former PTO to invest in knowledge of equipment and to put price and quality first, leading it to become a first-class service provider. The company could use this in a narrative that combines historical genesis and retrospection.

Telenor has struggled to create a narrative about its successful development because it can neither draw on positive values such as trust, innovation, and cooperation, nor can it offer positive externalities to Norwegian society other than shareholder value. Key elements in Telenor’s success are related to transactional costs; legal contracts; distrust; and emphasis on price, quality, put-options, and shareholder value. Many may appreciate such features and values, but there is a lack of soft values or greater purpose. It is probably no coincidence that Baksaas made his comment about research and money making at a closed seminar that was shareholder-friendly; it probably would have backfired if he had said it in public.

George Orwell’s famous aphorism from 1984—“Who controls the past controls the future … who controls the present controls the past”—has been cited in support of narratives that are performative.Footnote 184 It does not sit well with this story. Those who control the past, Telia and Ericsson, do not control the present, and those who control the present—in as much as Telenor does that—do not control the past.