Introduction

The Scotch whisky industry is one of the UK’s key export earners, contributing £5.5 billion to the UK economy,Footnote 1 and it underpins the international spirits portfolios of Diageo (e.g., Johnnie Walker Black Label) and Pernod Ricard (e.g., Glenlivet). Firms producing Scotch whisky—and their highly influential trade association, the Scotch Whisky Association (hereafter, SWA)—engage in various policy matters, especially taxation and access rights to all international markets. Given the global consumption of Scotch whisky, it is of little surprise that the SWA is a seasoned geopolitical actor interacting with the regulatory and legal systems in most major economies. Indeed, the industry’s success owes much to the endurance and political skill of the SWA as an outward-looking organization as well as its ability to channel collective action among its members at crucial periods in its history.

The SWA was formed in 1942 and became a limited company in 1960. The origins of the SWA, however, are in the early attempts of the grain whisky trade to establish a viable trade association for the express purpose of controlling prices. Following several failed attempts between 1856 and 1876, the 1877 merger of six grain distillers to form the Distillers Company Limited (hereafter, DCL) created “an Association in perpetuity.”Footnote 2 The industry progressed with gradual consolidation under the auspices of DCL for two decades. However, the need for a new trade association was prompted by the prospect of extensive political interference after a precipitous increase in excise taxes in the 1909 “People’s Budget” of the new Liberal government. The Wine & Spirits Brand Association was formed in 1912, from which the Whisky Association (WA) emerged in 1917 as a dedicated champion of Scotch and Irish whisky interests. The WA was located in London—the heart of the UK’s political system, with a general purpose committee inaugurated in Edinburgh in 1918 under the chairmanship of DCL’s William Ross.Footnote 3 The importance of the industry collective, and its anchoring in the leadership of DCL, was evident in the association’s response to Prohibition. Funds raised from the WA’s member firms were channeled via the WA to whisky importers who lobbied as independent entities in their own jurisdictions. William Ross, for example, occupied a prominent role in the International Alliance of Opponents of Prohibition, which was formed in 1922.Footnote 4

Brands such as Dewar’s and Johnnie Walker were established in the 1800s.Footnote 5 For example, John Walker, a Kilmarnock grocer had “dabbled in whisky retailing through his shop” prior to his son joining the business in 1856. Within six years, they were selling half a million liters per annum, with the Red Label and Black Label marques created in 1908.Footnote 6 George Ballantine and the Chivas Brothers were also shopkeepers who created their own house vattings that became their brands, and whisky blender John Dewar was the first to sell branded whisky in bottles. These brands were marketed internationally prior to World War I via family networks of agents in the English-speaking world. John Dewar & Sons Ltd. established a London branch office in 1891, and had branch offices in New York, Calcutta, Sydney, Melbourne, and Johannesburg by 1914. Similar structures and agency networks were established by Buchanan’s, John Walker, DCL, and Arthur Bell. By 1914 industry exports were some 39 percent of sales, the bulk of which was to the United Kingdom’s colonies and the United States.Footnote 7 Their continued growth required protection from both domestic and international regulatory interference as well as from potential threats in markets where they were not in full control of their brands’ distribution, stocking, and pricing policies. Their ability to control their destiny beyond their own boundaries, especially in the international marketplace, was rudimentary and thus required both interindustry cooperation and the assistance of their trade association.

Although marketing was an established and professional endeavor for Scotch whisky firms and was of preeminent importance to the industry, paradoxically it was the preeminence (that is, the unique qualities and properties) of the product that “provided whisky men with an unrivalled marketing opportunity”; yet “only Johnnie Walker could claim to be marketed as a worldwide range of brands by the 1970s.”Footnote 8

A central aim of the SWA after 1945 was to “protect the industry’s interests in the overseas markets by seeking legal recognition and enforcement of the principle that Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland.”Footnote 9 “Whisky” is generic, denoting a liquor produced by the distillation of cereal grains that impart flavor and aroma. Scotland is the largest producer of whisky,Footnote 10 but Canada, Ireland, and the United States are also important suppliers. Scotch whisky is a particular type of whisky, but “Scotch” denotes provenance; specifically, that this whisky has been distilled and matured in Scotland for at least three years, though many of the leading brands of Scotch whisky, for example Diageo’s Johnnie Walker Black Label, are matured for twelve years. Hence, Scotch denotes both provenance and maturity. Because whisky is consumed globally, the SWA has had to campaign in domestic and international markets to protect the integrity of Scotch whisky.

However, the SWA’s view of what constitutes Scotch whisky has not always been consonant with public understanding of this term. For example, as we show below, use of Scottish imagery—clan chiefs, glens, and highlands—and ambiguous nomenclature—might convince the public that a spirit is Scotch whisky without this marque. Similarly, did the term “blended Scotch whisky” imply that the spirit was composed of only Scotch whiskies or that a proportion of Irish whisky was used in the blend?Footnote 11 Furthermore, public response to the ways in which companies altered their branding sometimes undermined or obscured the visibility of “Scotch whisky.” For example, the Johnnie Walker brand evolved from the original brand name of Alexander’s Old Highland Whisky, which was referred to by the public as Walker’s whisky, Kilmarnock whisky, and Square-bottle whisky. Johnnie Walker’s brands of Old Highland, Very Old Highland, and Extra Special Old Highland were commonly referred to by the public as White Label, Red Label, and Black Label.Footnote 12

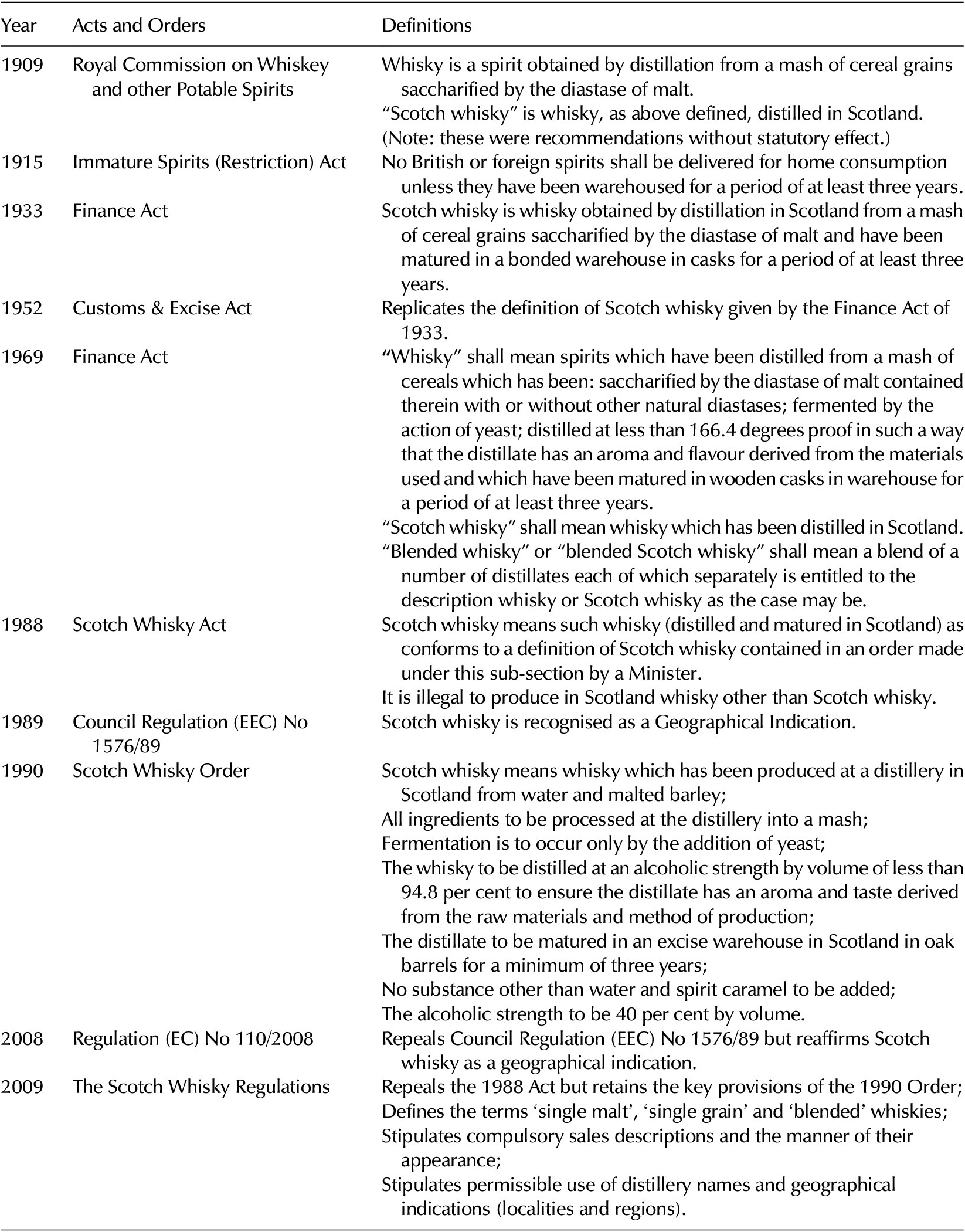

Clearly, the terminological issues surrounding Scotch whisky were complex and required the SWA to exercise considerable political influence. For example, although a UK statutory definition of Scotch whisky has existed since 1933, there was no such definition for whisky and blended whisky until 1969 (Table 1). Another problem was that the Acts of 1933 and 1969 did not define Scotch whisky as an appellation; they applied only to Customs and Excise (or Exchequer) policies, not the protection of producers or consumers. Appellations are a type of registered trademark recognizing the legal rights of their owners to sell products using the name of a particular region, for example, Burgundy wine and Idaho potatoes. By facilitating actions for infringement, these rights either eradicate or limit misrepresentation while simultaneously benefiting producers and consumers.

Table 1. Timeline of UK parliamentary acts and orders related to Scotch whiskey

Sources: Final Report of the Royal Commission on Whiskey and other Potable Spirits; 5 & 6 Geo. 5, c.46, s.1; 23 & 24 Geo. 5, c.19, s.24; 15 & 16 Geo. 6 & 1 Eliz. 2, c.44, s.243 (b); c.32, Schedule 7: s.1; c.22, s.1, s.3; S.I. 998; S.I. 2890, s.2; s.3; s.6; s.8; s.10.

It was not until 1988 that legislation specific to the definition of Scotch whisky was enacted (see Table 1). Prior to this date, the industry operated at a disadvantage when forced to protect its marque in rapidly growing European markets in which appellations were recognized.Footnote 13 Although the Scotch whisky industry embraced internationalization relatively early, with exports accounting for some 40 percent of total industry sales by 1914,Footnote 14 exports have dominated the industry’s fortunes since 1945, with a particularly precipitous increase from the late 1960s to the early 1980s.Footnote 15

Our analysis of the Scotch whisky industry complements and extends topical debates in business history, strategic management, and the historical evolution of brands in alcoholic beverages. Specifically, our article informs a wider debate on the role of trade associations and their interactions with governments, a key aspect of nonmarket strategy. As strategic organizations in their own right, trade associations are active agents of industry self-regulation.Footnote 16 Scholars in strategic management have identified trade associations as pertinent to the field of corporate political activity (hereafter, CPA),Footnote 17 but calls for comprehensive analyses of how trade associations actually operate remain largely unanswered. Indeed, some of the most recent work suggests that a comprehensive understanding has been hindered because associations have been studied by too diverse a range of disciplines.Footnote 18 Some scholars have emphasized the unique position of business historians, with their archive-based evidence, to enrich the understanding of nonmarket strategies.Footnote 19

Historians have added to a body of research on litigation between firms that has featured prominently in analyses of brands in alcoholic beverages. From the mid-nineteenth century, producers of famous champagne and cognac brands—Moet & Chandon, Ponsardin (Veuve Clicquot), Hennessy, and Martell—were active combatants in the courts.Footnote 20 Firms producing Scotch whisky also became embroiled in court actions. However, this litigation was not motivated simply by a desire to protect a company’s brand but also the marque of “Scotch.” Indeed, as we indicate below, the SWA, although not identified as a plaintiff, was the instigator of many actions in which a company’s brand and “Scotch” were being misrepresented.

Appellations were crucial to the evolution and growth of the European wine industry during the nineteenth century. Port was officially recognized as an appellation in 1756. Alessandro Stanziani has argued that the evolution of the appellation d’origine contrôlée wine classification in France was important because it helped prevent the names of wine regions—Bordeaux, Champagne, and Cognac—from becoming generic.Footnote 21 Similarly, the first Spanish Wine Law (1933) referred to Jerez as a Denomination of Origin. One important consequence of an appellation becoming legally recognized and protected is the generation of a strong and symbiotic relationship between company brand and appellation: wine and spirit brands indicate both trade origin and geographical provenance. For example, champagne can only be produced using grapes harvested in the Champagne region. In contrast, Scotch whisky is made using grains that are often produced outside Scotland, but to qualify as “Scotch whisky” the whisky must be distilled and matured in Scotland. Another consequence is to foster bilateral agreements between countries.Footnote 22

Blended and bottled Scotch whiskies have always dominated Scotch whisky production and exports. In 2018 the former accounted for 65 percent of both volume and value of exports, with bottled single malt comprising 10 percent of volume and 28 percent of value. The remainder is largely Scotch whisky shipped in bulk. Similarly, the largest grain distilleries—Diageo’s Cameronbridge and William Grant & Sons’ Girvan—have annual capacity of 110 million liters per annum (mlpa). By contrast, the largest malt whisky distillery, Pernod Ricard’s Glenlivet, has annual capacity of 21 mlpa; and Edrington Group’s Macallan, the mostly highly prized single malt whisky, has annual capacity of 15 mlpa. Although there exist many famous blended and single malt Scotch whisky brands, including Johnnie Walker, J&B Rare, and Macallan, these brands became iconic despite Scotch not being recognized as an appellation until 1989.Footnote 23 This latter observation begs the question: Would Johnnie Walker have become a global brand if Scotch whisky was perceived to be generic?Footnote 24 Its success before the early 1900s has been attributed to its remarkably consistent quality. Until that time, the firm had largely eschewed branding and advertising.Footnote 25

The inability to register “Scotch” whisky as an appellation in the United Kingdom until the late twentieth century placed the SWA at a significant legal disadvantage when trying to protect “Scotch” in international markets, especially continental Europe, where registered appellations benefited from an unqualified right to protection. The major international protocols safeguarding these appellations date to the Madrid Agreement for the Repression of False or Deceptive Indications of Source on Goods in 1891 (hereafter, Madrid Agreement) and the Special Union for the Protection of Appellations (hereafter, Special Union) established by the Lisbon Conference in 1958. The implications of the Madrid Agreement and the Special Union and the extent to which they debarred court actions are discussed in subsequent sections. Because Scotch whisky was neither wine nor a wine-based product, courts in the United Kingdom were empowered by the Madrid Agreement to determine whether Scotch whisky was, in fact, being misrepresented. The Special Union prohibited the sale of wines and spirits accompanied by terms such as “kind,” “style,” or “type” even when the true origin of the product was indicated—for example, “British sherry.”Footnote 26 However, because the United Kingdom did not accede to the Special Union, it was not strictly illegal to sell Scotch whisky using a variety of ambiguous terms. Consequently, before 1989, the defense of Scotch whisky relied on the precarious legal action of passing-off. Essentially, passing-off is concerned with misrepresentation, and it was “traditionally confined to misrepresentations that the goods, services or business of the defendant were those of the plaintiff or closely connected with him.”Footnote 27

This article also complements on-going debates because it focuses on the nonmarket activities of the SWA to secure legislative changes in the United Kingdom and Europe. Our data is based on a rich archive of previously confidential government letters and official memoranda, in addition to a portfolio of domestic and European litigation. We argue that the Scotch whisky industry’s ascendency to international dominance owed much to the successful lobbying activities of the SWA. Our analysis is facilitated by reference to earlier works that were based in part on prior access to the DCL archive, the research of archivists, and a compendium of industry data.Footnote 28 Finally, we refer to recent literature that places the Scotch whisky industry at the center of key themes in strategic management.Footnote 29

This article proceeds as follows. In the next section we discuss the relevance of trade associations to CPA and contextualize this within business history. We then explain why litigation in the United Kingdom was necessary and demonstrate that the SWA’s actions were hampered by the absence of an appropriate statutory definition of Scotch whisky. We extend the analysis to Europe, especially landmark judgments in Belgium following the collapse of negotiations to coordinate liquor regulations at the Council of Europe. This is followed by an examination of the SWA’s long history of lobbying to secure increasingly rigorous statutory definitions of Scotch whisky in the United Kingdom, culminating in the Scotch Whisky Act of 1988 and subsequently enshrined in European Economic Community (EEC) Regulations of 1989. We then present our conclusions.

Trade Associations in Historical Perspective

It has been suggested that trade associations were not actively engaged in political lobbying before 1945,Footnote 30 but Tony Freyer notes that their involvement in politics was fostered by the Depression and the need to promote a coordinated and restrictive environment for business. However, Freyer argues that the survival of trade associations post-1945 was threatened because they were blamed for stifling competitiveness.Footnote 31 Nonetheless, trade associations survived. In the United States, proponents of resale price maintenance ensured that trade associations acted as intermediaries between citizens and the state. Thus, trade associations gained a public regulatory function.Footnote 32 Even the advent of antitrust and labor laws did not extinguish the cozy “dinner club” behavior common of trade associations and their price-fixing activities.Footnote 33

For Luca Lanzalaco, business interest associations significantly impacted the evolution of capitalism by fostering experimentation with different models of collective action. Lanzalaco distinguishes two different types of business interest association: trade associations and employers’ associations. Trade associations, by their nature, are delimited by sector, category, or product. Employers’ associations tend more toward a nonsector-specific mode of organizing that reflects the territorial configuration of the labor market on which they depend. Both are subject to a challenge that trade unions do not confront: managing the diversity of interests that they represent. Their main advantages to both their membership and society are based on information exchange, improved decision making, and actions that support and complement markets.Footnote 34

After these associations consolidated, “their strategies and policies may influence the evolution of firms . . . by promoting specific types of industrial and economic policy.”Footnote 35 The transition from the guilds was based on merchants’ growing recognition of the need for coordinated economic development via collective action and political lobbying.Footnote 36 Although membership of the merchant guilds that emerged in the United States in the early 1800s was voluntary,Footnote 37 they were conceived as collective attempts to overcome the void between informal reputation mechanisms and absent state regulations.Footnote 38

Business historians have explained how industrial and corporate change emanated from the socio-political activity of trade associations. William Becker described how the US wholesale hardware association instigated an approved list of traders to strengthen producers’ price agreements, thereby supporting an alternative organizational form to the multifunctional and vertically integrated firm.Footnote 39 Extending the debate to “legitimacy,” Gunnar Svendsen charted the political coalition that emerged between the Danish Dairies Buttermark Association and the Danish state that led to legislation in 1906 stipulating that Danish dairies had to use the Lur brand on Danish butter exports. However, this cooperation did not survive; the state essentially expropriated the Lur brand as a national trademark in 1911, prompting the dissolution of this trade association.Footnote 40 Conversely, a study of regulatory capture in the Finnish forestry and paper industry between the late 1960s and early 1970s demonstrates that policy makers and the industry’s trade association collaborated to protect Finland’s natural resources from overexploitation.Footnote 41 Industry-level endorsement or certification models to protect reputations and engender legitimacy are evident in other industries.Footnote 42 Recently, Teresa Da Silva Lopes explained how UK chocolate producers sought legitimacy via the Society of Friends and by third-party certification and endorsement, a prototype of the Fairtrade collective.Footnote 43 Patricio Sáiz and Rafael Castro point to a wide-ranging academic interest in this relationship.Footnote 44 Such activities often complement firms’ efforts to safeguard the legitimacy of their trademarks and the economic rents thereby obtained.

Nonmarket strategies are essential to firms because government policy affects the competitive environment.Footnote 45 A powerful trade association acting as an “insider” is a potent mechanism by which firms can obtain preferred regulations. Howard Aldrich commented that trade associations enjoy access to government officials that is quite different from other associations.Footnote 46 Because trade associations operate at the nexus of collective strategy and the nonmarket environment, they enhance their members’ performance by influencing nonmarket forces.Footnote 47 Notwithstanding the impressive body of literature on nonmarket strategy,Footnote 48 some of which discusses discrete silos (e.g., corporate social responsibility and corporate political activity),Footnote 49 little is known about the channels through which firms engage in nonmarket processes, particularly in a multijurisdictional context.Footnote 50 This lacuna has prompted calls for insights from history and legal studies, such as Andrew Perchard and Niall MacKenzie’s exposé of organizational path dependence at the British Aluminium Company Ltd. and its practice of hiring senior military and top-ranking civil servants.Footnote 51

What Is Whisky? Litigation in the UK Market

Litigation was, and remains, a key part of the SWA’s game plan to protect the integrity of “Scotch whisky.” By the 1990s, it was reported that the SWA had initiated over one hundred actions across the globe. Although the SWA was not named as a plaintiff in all proceedings, it often requested member companies to bring actions.Footnote 52 Compared to the SWA, companies were in a strong position when petitioning the courts to protect their registered trademarks. The SWA was seeking to protect a genus, Scotch whisky, which was not registered as such, and for which only the risky legal remedies of passing-off and unfair competition existed.Footnote 53 In a UK context, the broad parameters governing the SWA’s legal activity originated from the Madrid Agreement.Footnote 54 We note here that the 1994 Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, which is binding on all members of the World Trade Organization, refined and enhanced the global protection afforded geographical indications (that is, appellations).

With the exception of wine, Article 4 of the Madrid Agreement entrusted the courts in each Member State the responsibility for determining which appellations were generic. Therefore, since 1891, the Scotch whisky industry operated in a domestic market where “only the United Kingdom courts can authoritatively determine, in any particular case, whether a given description is unlawful.”Footnote 55

Consequently, UK courts needed to demarcate Scotch whisky from whisky. In 1939, the Glasgow merchant Henderson & Turnbull Limited was successfully sued for applying the false trade description “Scot’s Whisky” to whisky that was a blend of 33 percent Scotch pot still whisky and 67 percent Northern Irish patent still whisky, contrary to the Merchandise Marks Acts.Footnote 56 The High Court of Justiciary ruled that “when whisky is sold as Scotch whisky, the representation that it is Scotch whisky carries the meaning that the entire contents of the container in which it was sold were distilled in Scotland.”Footnote 57 According to Charles Craig, the practice of blending Irish patent still whisky with Scotch malt whisky was pervasive since at least 1898.Footnote 58 Such blending occurred because the characteristics imbued in a blended whisky derive from the pot still malt whiskies, not the (neutral) patent still grain whiskies. Even experts could not distinguish between two blended products containing identical pot still components blended with different patent whiskies. Congenerics are complex alcohols from the same chemical series as ethyl (neutral) alcohol that remain in malt whisky after pot distillation, but which remain as only a trace in grain whisky due to the patent distillation process. Most consumers can likely distinguish between Scottish and Irish pot still whisky and between the malt whisky derived from the different Scotch whisky-producing regions. The High Court noted that the contemporaneous definition of Scotch whisky (which we discuss below) would, “cover in terms either “Bourbon” whisky or “Rye” whisky, if either of these were in fact manufactured in Scotland.”Footnote 59

Litigation in 1905 precipitated the first formal definition of Scotch whisky. The summonses alleged that a blend of Scotch (or Irish) whiskies was not of the “nature, substance and quality” of the liquor legally defined as whisky, thereby breaching the Sale of Food and Drugs Act of 1875.Footnote 60 This meant that unlike malt whisky, grain or blended whisky could not claim to be authentic Scotch whisky. The case pitched small malt distillers—reeling in the aftermath of Pattison’s financial collapse and the subsequent slump in whisky salesFootnote 61 —against the better capitalized DCL and its arch-rival North British. Two years of court wrangling ensued.Footnote 62 A Royal Commission was finally established in 1908 to investigate whisky and potable spirits, and its final report was published in 1909.Footnote 63

The Royal Commission supported the views of the blenders and grain producers: their product was no lesser a whisky. This commission provided the first formal definition of whisky and Scotch whisky. “Whisky” is a spirit obtained by distillation from a mash of cereal grains saccharified by the diastase of malt, while “Scotch whisky” is whisky, as above defined, distilled in Scotland.Footnote 64 However, these definitions were only recommendations. Further, the Royal Commission indicated there was no need to make it compulsory that bottle labels contain designations of origin, composition, or age because sufficient protection existed in the United Kingdom from the Sale of Food & Drugs Acts and the Merchandise Marks Acts.Footnote 65 The first official definitions of Scotch whisky were provided by the Finance Act of 1933 and the Customs and Excise Act of 1952. The official UK definition of Scotch whisky in the Finance Act of 1969 remained largely unchanged until 1990 (see Table 1).

The admix trade refers to the export of bulk single malt whiskies to foreign countries, where it is mixed with local spirits. The admix trade was not illegal per se if the end-product was labeled accurately. Both the DCL and the SWA had concentrated their power in Scotland, which allowed them to be consistent in their approach to controlling bulk shipments by imposing stricter bottling criteria. Nevertheless, bulk shipments of malt whisky grew rapidly throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Japan accounted for nearly 70 percent of bulk malt whisky shipments, raising wide-spread concerns that this trade would reduce sales of Scotch blends in markets such as the United States and Australia and damage the image of whisky “in the sense that the uniqueness of the product was diminished.”Footnote 66 However, Japanese whisky, which adhered closely to Scotch whisky in terms of quality, ingredients, and the manufacturing process, failed to make a significant impact on the international stage until the 1990s.Footnote 67 That is when Suntory, the leading Japanese whisky firm, acquired secure supplies of Scotch malt whisky for its own Japanese whisky blends and built a platform from which to establish an international branded portfolio. It made strategic investments in the publicly listed Macallan-Glenlivet in 1986 (increasing its shareholding to 25 percent in 1991) and in privately owned Morrison Bowmore in 1989 (taking full control in 1994).Footnote 68

UK legislation prescribed that bottles of liquor had to be accompanied by labels indicating alcohol by volume (abv.) and the name of the country in which the liquor originated. When a liquor was described in terms that falsely suggested it originated in a particular country or locality, this description also had to include the true country of origin.Footnote 69 Nevertheless, the use of misleading labels was a perennial problem for the SWA. Terms such as “Whisky Flavoured British Spirit”Footnote 70 accompanied bottles often containing Irish, not Scotch, whisky, or a mixture of 80 percent Cyprus brandy and 20 percent Scottish malt whisky.Footnote 71 Similarly, the labels Whisky McAndy, The Cameron, and Highland Bonnie evoked Scotch whisky imagery but were applied to bottles containing neither whisky nor Scotch whisky.Footnote 72 Other labels breached the Food Labelling Order by not listing the ingredients, “which are alleged to be blended with fine old Scotch whisky.”Footnote 73

Another problem facing the industry was the mis-selling of foreign liquor in the United Kingdom. For example, Danish liquor was imported and sold as Danish whisky, even though it was allegedly made from unmatured potato spirit, not grains. The SWA claimed that this whisky was passed-off in Scotch whisky bottles,Footnote 74 but it was unable to convince the Food Standards & Labelling Division (hereafter, FSLD) to initiate litigation. One obstacle was that of Her Majesty’s Customs and Excise (hereafter, HMCE), which was formed in 1909 by the merger of HM Customs and HM Excise. The HMCE had sampled this Danish whisky and pronounced it “satisfactory.” Notwithstanding a possible breach of the Labelling Order, the FSLD was emphatic that “we would want something more than mere unsubstantiated allegations . . . to persuade us that it is worthwhile trying to get a food and drugs authority interested.”Footnote 75 Undeterred, the SWA insisted that the FSLD contact British ministers in Copenhagen to determine the composition and maturation of this Danish whisky,Footnote 76 following which the Danish producer agreed to submit a sworn certificate with all future shipments attesting to the following facts: the whisky was a blend of neutral grain spirit that did not contain potato distillates and that all of the spirits were aged for a minimum of three years.Footnote 77

A related problem was the sale of “Scotch” whisky using ambiguous nomenclature. As noted in the introduction, in the United Kingdom only the courts could determine whether the sale of wines and spirits using the terms “type” or “style” was prohibited. But because each case had to be determined on its merits, there remained considerable leeway for whisky to be sold as Scotch whisky. This latitude generated confusion that was satirized by cartoonists (Figure 1). It also anticipated litigation on the fundamental question: What is Scotch whisky?

Figure 1. Cartoon satirizing sales of imitation Scotch whisky, 1947

Source: MAF 101/699, TNA. Reproduced by permission of The National Archives.

Between 1950 and 1951, a protracted legal case ensued involving false labeling of whisky by London-based merchants Messrs. Henry Lewis Ltd. The litigation pertained to “Old Masters 100 per cent Whisky, produce of UK, and Ireland” and “Glen Gor fine old Scotch Whisky.”Footnote 78 The defendants were accused of supplying bottles purporting to contain whisky but which were “a mixture of Whisky, Rum and dilute rectified Spirit.” One expert witness claimed that although the samples had a definite flavor of rum, “[c]hemical analysis alone was not a conclusive measure for establishing whether or not a product was genuine Whisky.” Another expert described the two samples as “unadulterated Irish and Scotch Whisky, respectively,” and commented that the apparent presence of rum could be a function of storing whisky in old sherry barrels prior to bottling. It was acknowledged that whisky was also stored in barrels that previously contained port and rum.Footnote 79 Nonetheless, the defendants were found guilty, with total fines of £300, costs of almost £1,000, and with one defendant being jailed for three months.Footnote 80 In UK criminal law, a fine is a sum of money ordered to be paid to the Crown by an offender as a punishment for his offense. Costs are the charges that a solicitor is entitled to make and recover from the client or person employing the solicitor in remuneration for professional services.

However, the case was appealed, and the central question was, again, “What is whisky?” The original prosecution was claimed to be flawed and that the plaintiffs did not prove that the whisky being sold was not whisky. In the appeal, the defense counsel stated, “[N]o one knows [what whisky is]. There is no standard as to what Whisky actually is.”Footnote 81 The presiding magistrate agreed that the case had not been proven beyond reasonable doubt and thus the case was overturned. A trade publication concurred that there was no standard by which whisky could be defined, and it suggested that the weight attached to the judgments of chemical analysts was not fair: “[T]here is a limit to the powers of the analytical chemist. . . . It has been proved, time and time again, that chemistry has no re-agent capable of determining qualitatively, let alone quantitively, the basic material of aromas or odours of organic origin.”Footnote 82

Chemical analysis of foodstuffs accelerated from the late nineteenth century following growing public concerns about food adulteration.Footnote 83 The adverse consequences of consuming “unwholesome” food such as beer containing arsenic or beef from diseased cattle seem obvious enough. Food adulteration also meant consumers were cheated economically because they were paying a higher price without knowing the true qualities (or composition) of the product. According to Benjamin Cohen, adulteration involved “matters of trust, legitimacy, and authenticity.”Footnote 84 For the SWA, “adulteration” meant that the composition of whisky, sold as Scotch whisky, did not conform with even the basic definition laid down by the 1909 Royal Commission (see Table 1). Although adulterated whisky was not necessarily unwholesome, the economic consequences of the sale of this spirit as Scotch whisky were potentially severe. For example, in the minds of consumers, Scotch whisky would not be perceived as a product of Scotland and the term would become generic, thereby ruling out any possibility of Scotch whisky securing appellation status.Footnote 85

The above cases as well as others generated difficulties for the SWA. Unlike litigation involving Champagne,Footnote 86 in which the name of the wine is identical with the locality in which it is produced, whisky had not monopolized to itself the names “Scotland” or “Scotch.” Further, to what extent did the distinctiveness of Scotch as applied to whisky depend on this marque compared with other indications of Scottish origin, for example, tartan imagery? As the Messrs. Henry Lewis case demonstrated, because it was not possible to prove what was Scotch whisky, producers of the genuine product who employed implicit indications of Scottish provenance as part of their brand were at risk of suffering financial damage. Although Scottish origin was an indicator used in relation to whisky, the term “Scotch” by itself did not mean “Scotch whisky.” Was the SWA entitled to seek protection of “Scotch” when this did not apply exclusively to Scotch whisky?Footnote 87

A crucial consideration in passing-off cases is whether consumers are misled,Footnote 88 but determining this is risky. In litigation involving a Uruguayan company, J. Walter Thompson, of Argentina, conducted a street survey of respondents in Montevideo to gauge consumer perceptions of Gregson’s Fine and other indirect indications of Scottish origin. It was reported that 56 percent of the respondents believed the liquor was produced in Scotland while only 40 percent thought it was imported.Footnote 89 Indirect use of indications suggesting Scottishness would not diminish goodwill in Scottish indicia if consumers did not expect the product to be Scottish. Successful litigation involving the sale of whisky as “Scotch whisky” when it was a blend of Scotch whisky and whisky from other nations required that consumers expected the liquor to be distilled in Scotland (see Table 1). It was argued that misrepresentation endangered the reputation of Scotch whisky because it weakened the distinctiveness of indications of Scottish origin when used in relation to Scotch whisky.Footnote 90

Perhaps the most famous passing-off case involved John Walker & Sons Limited in 1970.Footnote 91 Most of the plaintiffs in this action were subsidiaries of DCL and members of the SWA.Footnote 92 The two defendants were Henry Ost & Co Ltd. and Vinalco S.A. Productora Ecuatoriana de Licores. It was alleged the first defendant sold deceptive labels to the second defendant, who used these labels to pass-off as Scotch whisky an admix consisting of Scottish malt whisky and local cane spirit, and that both defendants colluded to sell the admix as Scotch whisky in Ecuador. This litigation was important to the SWA because total shipments of Scotch whisky to Ecuador between 1959 and 1965 were 1.5 million bottles, of which the plaintiffs exported around half. Ecuador was a relatively small market in the context of Scotch whisky sales, both in absolute terms and relative to South America and Central America.Footnote 93 However, by the late 1970s, the importance of South America as an emerging market of some significance was apparent in export sales to close neighbor Venezuela.Footnote 94 A negative verdict would have damaged SWA members’ sales to Ecuador and throughout South America.

Again, the key issue was: What did consumers in Ecuador understand by the term “Scotch whisky”? The use of indirect indications of Scottish origin—“White Abbey . . . Blended Very Old Whisky . . . Scotch Malt” and “Scottish Archer . . . De Luxe Blended Whisky . . . Scotch Malt Glenvale Distillery” in addition to tartan colors and a Tam O’Shanter led customers to believe they were buying genuine Scotch whisky.Footnote 95 The plaintiffs established that in Ecuador, Scotch whisky meant a blend of Scotch whiskies, not a blend of Scotch whisky and local liquor. One feature of this case that is especially pertinent to this article is that it reaffirmed the rights of producers to sue even when their own brands were not being misrepresented.Footnote 96

The SWA and the Protection of Scotch Whisky in Europe

To facilitate reconstruction after 1945, European politicians focused on the establishment of a Common Market that involved major directives on antitrust and competition policy.Footnote 97 There are two reasons why the Scotch whisky industry provides a useful case-study for discussing the evolving institutional environment within the EEC. First, the SWA and its members featured in test cases involving conflict between the Treaty of Rome (1957) and Member States with the potential to damage supply networks based on exclusive dealerships. For example, Vat 69, a Scotch whisky, was exported by William Sanderson & Sons Ltd. to a distributor with sole marketing rights in West Germany. Parallel imports of VAT 69 from the Netherlands and South America threatened both this distributor and the trademark “VAT 69” owned by Sanderson, a DCL subsidiary and member of the SWA.Footnote 98 Second, the SWA sought consonance between UK and EEC regulations on spirits.

The pressing issue for the SWA was how to protect the designation “Scotch whisky” when dealing with legal systems that were quite distinct from the United Kingdom.Footnote 99 Prior to negotiations on the UK’s accession to the EEC, there had been a growing admix trade across Europe prompting several legal disputes. The SWA sought from the UK government a tighter domestic legislative definition of whisky to counter fraudulent sales of Scotch whisky in Europe. Whisky-type beverages comprising mixtures of malt whisky (not always from Scotland), neutral spirit distilled from the cheapest materials (not necessarily grain-based), and without maturation (not matured in barrels for at least three years) were being sold throughout the Common Market.Footnote 100 Problems in Italy and Spain, for example, were already apparent by the late 1950s, before the admix trade accelerated at the end of that decade. The SWA insisted HMCE issue a Certificate of Age to deter bulk shipments of three-year-old Scotch whisky for blending abroad and its subsequent passing-off as Scotch whisky. Official correspondence reveals that the SWA hoped to secure the elimination of paralleling via the black market at a time when limited supplies undermined authorized distributors and eroded the profit margins of SWA members.Footnote 101 It was usual for overseas sales to be handled by single distributors.Footnote 102 For example, J&B Rare, a leading brand, had been distributed in the United States by New York-based Paddington since 1937 under an exclusive distribution agreement. Paddington became part of the US conglomerate Liggett Group, which was ultimately acquired by Grand Metropolitan, thereby consolidating brand and distributor within the same firm.Footnote 103 Similarly, Guinness eventually acquired Schenley, the long-time US distributor of many of the major brands of its recently acquired DCL, including Dewar’s and Gordon’s, to “strengthen the British company’s control over its brands in the United States.”Footnote 104 This was trade in genuine-branded Scotch whisky as opposed to an adulterated product. With supply shortages forcing distillers to limit what they could ship to their authorized distributors, robust demand in Italy was met by Scotch whisky bought from importers in other countries, where demand was less robust. It was then imported into Italy and sold profitably at a price that undercut the authorized distributor. The British embassy was reluctant to engage with the SWA on this matter, instead arguing that finding a solution was the SWA’s responsibility and suggested that a reduction in profit margins would make selling Scotch whisky less alluring to unauthorized distributors.Footnote 105 Similarly, the SWA was unsuccessful in persuading the Board of Trade through the conduit of the British embassy in Madrid to apply pressure on the Spanish government to restrict the operation of a newly constructed distillery in Madrid that intended to produce a Scotch-type whisky.Footnote 106

Against this backdrop, the Council of Europe in 1958 established a Committee of Experts on Wines and Spirits (hereafter, Committee). The objective of this Committee was to “lay down the general lines of a common policy for the production and marketing of vine products and spirits and for the protection of trade names which are warranties of origin.”Footnote 107 The Committee sought coordination of domestic regulations, international agreement on definitions, and the suppression of false or misleading indications of geographical origin.Footnote 108 UK officials acknowledged that the “primary purpose of the United Kingdom’s participation in the work of the Council of Europe Committee of Experts was to try to secure . . . a satisfactory definition of ‘whisky.’” Footnote 109 The SWA appointed its own representative to this Committee.Footnote 110

By the early 1960s, the Committee agreed that Scotch whisky should be protected as an appellation.Footnote 111 In 1961, the Committee’s definition of whisky corresponded to the UK’s definition of 1933 (see Table 1). Because of the different ways in which whisky was produced in Europe, the Committee recommended that regulations governing its production should conform to those of the major European whisky-producing countries—Ireland and Scotland—“in order both to preserve the distinctive characteristics of the whiskies and to respect—subject to international regulations governing appellations of origin—the manufacturing processes whereby each particular brand of whisky is produced.”Footnote 112

Nonetheless, by the mid-1960s, it was apparent that the divergent interests of European countries meant that an agreement was jeopardized.Footnote 113 The Committee was beset by disparate opinions on the scope of the drinks categories to be included in its recommendations. The biggest obstacle to progress was the failure to secure consensus on Article 14: “The Contracting Parties undertake to ensure in their territory . . . the protection of the geographical names, indications of source . . . and appellations of origin. . . . They prohibit any usurpation or imitation even if the true origin of the product is mentioned.”Footnote 114

Significant opposition to this article was raised by wine producers in Australia, Cyprus, and South Africa. The Australians argued that “Australian Burgundy” had been sold in the United Kingdom for over one hundred years and over 70 percent of Australian wine exports went to the United Kingdom, so any change in established wine names would be devastating. South African sherry producers argued that consumers would know that the true origin of the wine was Spain, and thus an indication of “South Africa” would not mislead them. Spanish producers were equally strong in their opposition: Xeres, Jerez, or Sherry could only be legitimately applied to wine products originating from the Jerez region of Spain.Footnote 115 These conflicts meant that the Committee never ratified a protocol on the definitions governing spirits. A comprehensive definition of whisky and other spirits was only provided in 1989 by EEC Council Regulation 1576/89.

Failure to achieve ratification of Article 14 was arguably a mixed blessing for the UK government. Acceptance risked political difficulties with the Commonwealth and threatened the government’s traditional policy of relying on UK courts to determine the veracity of descriptions applied to wines and spirits. The UK government acknowledged, however, that it “seemed right that we should try to help the industry by including in UK legislation a definition of ‘whisky.’”Footnote 116 By the late 1960s, the SWA was blaming the breakdown in Committee negotiations on the French preference to wait for the EEC to produce its own definitions. Even more galling to the SWA was that sales of imitation whisky in Germany exceeded exports of the leading brand of Scotch whisky to Germany. The SWA recognized that to protect the meaning of whisky and the geographic meaning of Scotch, “we shall be forced to continue to engage in legal action after legal action with all the hazards, delay and expense which these entail.”Footnote 117

The SWA was especially concerned about Belgian litigation in the 1960s, which was among the earliest initiated by the SWA in Europe.Footnote 118 Mr. Kirke of the SWA claimed that “quite a good drink” could be made consisting of just 15 percent Scotch whisky.Footnote 119 The SWA estimated that there were over one hundred brands of imitation Scotch whisky on sale in Belgium at the time, and that if a customer ordered a whisky without specifying the brand, they would “probably be given the locally-made product which in some cases could have cost only half the price of ‘Scotch,’ despite well-known brands of Scotch Whisky being on view in bars.”Footnote 120 The SWA acknowledged that failure to secure convictions in Belgium would have set a damaging precedent in case law:

If [we] are unsuccessful in that litigation I think we can conclude that the last opportunity of establishing our own definition of whisky in the Common Market will have been lost . . . [and we will be] faced with the increased competition of products cheaply made from neutral spirits and which masquerade as whisky, exports of Scotch whisky . . . [and these] are likely to be considerably less [quality] than they would be if the reputation and prestige of whisky had been upheld by suitable definitions.Footnote 121

In each action in Belgium, the SWA was named as a party and, in some cases, so too were some of its members.Footnote 122 The fundamental issues in this litigation were that Scotch whisky was imported to Belgium, mixed with neutral spirit, and then sold as whisky with the labeling “Blended Scotch Whisky,” “Duns Scot,” and “Old Scotch” to suggest it was genuine Scotch whisky.Footnote 123 Once again, this litigation highlighted the absence of a UK sui generis definition of whisky, which created more problems for the SWA. The defendant argued that it was valid to sell the admix liquor as whisky because this drink derived its taste and aroma from the genuine Scotch whisky used in its manufacture. Because the word “whisky” in isolation did not constitute a protected designation—it was a generic term denoting a type of liquor characterized by its taste—why was the SWA insisting on its definition of whisky? Doubts were expressed about whether use of the English language on the labels was illegal or deceptive because English was a universal language and its use in the sale of alcoholic beverages was ubiquitous.Footnote 124

Nonetheless, the SWA received a favorable verdict. Two aspects of this judgment deserve attention. First, the court emphasized that the purchaser must not be deceived. The Belgian public was unaware of the nuances of the English language and might not appreciate that “Scotch” could be used to denote Scottish origin. On this basis, the court found that the defendants had practiced a “deliberately dishonest manoeuvre” because they had juxtaposed bottles of the admix with bottles of genuine Scotch whisky. Second, the court ruled that the addition of neutral alcohol to whisky did not constitute whisky. As applied to Scotch whisky, blended meant a mix of different types of Scotch whiskies, not a blend of Scotch whisky and neutral alcohol.Footnote 125

Scotch Whisky: Securing a Definition

An official UK definition of Scotch whisky was enacted in 1990, but prior to that successive governments had adopted the definitions provided by the Royal Commission and recognized these were accepted by the public and the trade. Nevertheless, government officials questioned why the SWA had not filed a court case to establish the meaning of whisky: “It may be that they feel there is a possible risk that the case might go the wrong way—in which event, of course, their position would be seriously weakened.” Footnote 126 These doubts were expressed when the SWA was pressing the government for assistance in an upcoming court case in Belgium.Footnote 127 The SWA wanted the government to state that a court case in the United Kingdom would likely go in the SWA’s favor, even though it was an untested theory. Unfortunately, the UK government’s legal advice cautioned: “One cannot conjecture about a court’s decision on such a matter . . . although one would expect a court to take account of the meaning assigned to the word in the licensing trade and possibly the finding of the Royal Commission.”Footnote 128 As noted, in the absence of internationally agreed definitions, the SWA was obliged to protect the generic meaning of whisky and the geographical meaning of Scotch by litigating in foreign courts. The prospects of success were limited because, outside of HMCE and Treasury regulations, there were no UK definitions for whisky and blended whisky.Footnote 129 Exacerbating matters, foreign courts might question why Scotch whisky was defined in UK statute only in 1969.Footnote 130

Problems emerged for the SWA, and its forerunner the WA, during the interwar period when the industry faced restricted supplies of patent still whisky and had to deal with Prohibition in the United States, its main export market. With the active support of the UK government, the first problem was resolved by importing Irish patent whisky into Scotland, blending it with pot still whisky, and selling it as Scotch whisky.Footnote 131 Evidence from the WA revealed it had “considered the question of either registering a trademark or of obtaining from His Majesty’s Government some authoritative definition of ‘Scotch Whisky’ which should limit the use of that term.” Turning to Prohibition, it was noted that “firms domiciled in Scotland, who are of the highest repute and who conduct a world-wide trade in merchanting whisky . . . blend pot still whisky distilled in Scotland with patent still spirit distilled in Canada and . . . advertise the blend in Canada as ‘Scotch Whisky.’”Footnote 132

Another weakness in the Royal Commission’s definitions of whisky and blended whisky was that they did not specify that Scotch whisky had to be bottled in Scotland. It was customary for all types of Scotch whisky to be labeled with “Distilled in Scotland and bottled in the United Kingdom under Government Supervision.”Footnote 133 The SWA wanted this to be changed to “Distilled and Bottled in Scotland under British Government Supervision” to optimize the geographical indication of ScotlandFootnote 134 and curtail the adverse consequences of growing exports of bulk Scotch whisky during the 1950s, some of which fueled the admix trade.

London-based bottling interests resisted the move to “Bottled in Scotland” (hereafter, BIS), stating, “We have already expressed our unalterable objection to the proposed wording.”Footnote 135 The owners of J&B Rare claimed that as it was relatively cheaper to export Scotch whisky in bulk, marketing strategies could be used to persuade US consumers to switch from Bourbon to locally bottled Scotch whisky, and to trade up to BIS Scotch brands in the future.Footnote 136 London-based bottler Gilbey argued that the SWA’s definition placed its products at a disadvantage to BIS brands, even though they were an identical product.Footnote 137 The SWA ignored representations on the wording of labels made by Berry Brothers & Rudd, whose top selling US brand—Cutty Sark—was bottled in Scotland.Footnote 138 Cutty Sark was blended by Robertson & Baxter under a long-term agreement with Berry Brothers & Rudd. Propelled by sales in the United States, it was the first Scotch whisky brand to record overseas sales of one million cases.Footnote 139 What makes the SWA’s snub all the more remarkable was that Robertson & Baxter had been a key member of the SWA from its inception as the WA. James Robertson had acted as vice president of the General Council of the WA and continued in this role when the latter organization became the initial Council of the SWA in 1942.Footnote 140 Other key personnel from Robertson & Baxter were also prominent on the Council of the SWA until 1955. Thereafter, there was a gap in senior representation from the firm until 1964. It is tempting to speculate that the DCL was motivated to act unilaterally in these intra-industry discussions for strategic and financial reasons and because it was mindful of the competitive positioning of its brands in the important US market. Four brands—J & B Rare, Cutty Sark, and DCL’s Dewar’s and Johnnie Walker—accounted for a 50 percent share of this market.Footnote 141

Following threats by the DCL to politicize the struggle by contacting sympathetic members of Parliament, it appears that the UK government endorsed the SWA’s preferred labeling:

[A]fter laying the matter before Ministers . . . we should accede to the Scotch Whisky Association’s request to use the wording “Distilled and Bottled in Scotland under British Government Supervision” . . . [and] we have no option now but to accede to the request of the Scottish bottlers, who represent an overwhelming majority interest, and whose desire to make full use of geographical description on a product whose characteristics depend upon geography is understandable.Footnote 142

The SWA’s lobbying activity was also evident in the enhanced protection for Scotch whisky secured in the Finance Act of 1969. For some time the SWA had claimed that Scotch whisky exports to Europe were threatened because:

[W]e have found it a severe handicap that there does not exist in the United Kingdom a definition of the word Whisky or the description Blended Whisky and that the definition of Scotch whisky is not sufficiently precise in that it does not exclude cereal spirits distilled at such a high strength as to be practically devoid of flavour.Footnote 143

The SWA impressed upon the government the need for a clause in the finance bill “because [we] believe that something in an Act will impress overseas courts more than something in a mere Statutory Instrument.”Footnote 144 Following this campaign, new definitions were included in the Finance Act of 1969 (see Table 1). A confidential note laid bare the special treatment received by the SWA:

Although ostensibly for custom and excise purposes, the main reason for the inclusion of these definitions was to provide a statutory definition or definitions which could be cited by the Scotch Whisky Association or their members or associates in legal action overseas to prevent the passing-off of inferior spirits under the descriptions mentioned . . . actions were very difficult or failed because such statutory definitions in the UK did not exist.Footnote 145

Subsequently, a related problem was the production and sale of under-strength Scotch whisky in the United Kingdom and Europe because the Finance Act of 1969 did not specify the minimum strength for this liquor. By the early 1980s, the scale of this European trade was substantial. It was estimated that 20 percent of the EEC market was supplied by under-strength whisky, which, because of lower duty and brand-promotional expenses, was sold at prices substantially lower than the leading brands.Footnote 146 The SWA alleged that some Scotch whisky was being sold at strengths as low as 20 percent abv.Footnote 147 To overcome the threat posed by under-strength Scotch whiskies, the SWA increased its lobbying and proposed that an additional clause be inserted in the Finance Bill of 1984, specifying 40 percent abv. as the minimum strength of Scotch whisky, which Michael Jopling, the minister for Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food, agreed with. It was acknowledged, however, that this regulation would “protect the interests of a particular group of producers” and that “concern has been expressed that the SWA whose strongest members are DCL are creating a definition which could significantly disadvantage . . . independent traders.” This proposal provoked opposition from producers and bottlers of under-strength Scotch whisky, and the amendment was dropped.Footnote 148

How, then, was a more stringent bill successfully passed in 1988? A Private Member’s Bill, introduced by MP William Walker and supported by the SWA, sought a minimum strength of 40 percent abv. and to restrict the production of Scotch whisky to Scotland. The answer is that Walker’s constituency, Tayside North, was home to ten distilleries, and the SWA stressed that its campaign for a minimum 40 percent abv. standard addressed growing official concerns within the United Kingdom about EEC Regulations on Spirits, and it deployed this concern in its lobbying of ministers.Footnote 149

Walker’s bill was supported by the secretary of State for Scotland, by all Scottish MPs (except George Foulkes, within whose constituency was William Grant’s Girvan grain distillery), and two Scottish baronesses and one lord who farmed barley used in the production of Scotch whisky (Baroness Carnegy of Lour, Lord Mackie of Benshie, and Baroness Strange).Footnote 150 However, the bill also encountered substantial opposition from the Department of Trade and Industry. The department argued that the bill was contrary to the government’s general approach to wealth creation and competition; denied businessmen in Scotland the opportunity to produce something freely produced elsewhere in the United Kingdom; and reduced consumer choice. Senior ministers expressed doubts about the wisdom of prohibiting the production of under-strength whiskies in Scotland while the Home Secretary opposed the criminal penalties in the bill.Footnote 151

To break the deadlock, the SWA held a series of meetings with the relevant ministers. The SWA would not countenance any change to minimum strength or the requirement that Scotch whisky be produced exclusively in Scotland, but it was prepared to concede criminal penalties provided that effective alternatives could be substituted. Two solutions were eventually agreed to. The first was the SWA would secure an injunction to prohibit the sale of whisky that did not conform to the statutory definition set out in the Scotch Whisky Act of 1988 (see Table 1). This placed the SWA on a much stronger footing for instituting civil proceedings in the United Kingdom. The second solution was to restrict the production of Scotch whisky to Scotland and to safeguard the minimum strength requirement. Whisky producers who did not conform with the regulations forfeited their output to HMCE.Footnote 152

These pending EEC regulations were decisive in the UK government’s accommodation of SWA concerns that under-strength whisky could be produced in Scotland and be marketed as “Whisky—product of Scotland,” thereby undermining the prestige and quality associated with genuine Scotch whisky.Footnote 153 To overcome this threat, the SWA argued it was imperative that Walker’s bill be enacted to ensure that the UK statutory definition of Scotch whisky was incorporated into EEC regulations. Subsequently, in 1989, the first EEC regulation (EEC Council Regulation 1576/89) governing spirits stipulated:

Member States may apply specific national rules on production . . . description and presentation to products manufactured within their territories. . . . Where they are applied in pursuit of a quality policy, such rules may restrict production in a given geographical area to quality products complying with the specific rules concerned.Footnote 154

Scotch whisky is now subject to oversight by Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs. This government department, formed in 2005 by the merger of HMCE and the Inland Revenue, issues regulations covering all key processes involved in the production of Scotch whisky and the verification of its producers.Footnote 155 Legislation empowers the SWA to apply for court orders to stop the sale of “Scotch whisky” when it does not comply with the regulations.Footnote 156 Scotch whisky is also recognized in Europe as a geographical indication (see Table 1). A more specific definition was subsequently developed with additional protection for the traditional regional names associated with Scotch whisky.Footnote 157

Conclusions

We have discussed the multiperiod, multifaceted operations of the SWA as it sought to achieve a major objective: stronger legal recognition and protection of the appellation “Scotch whisky.” This article contributes to debates on the nonmarket activities of trade associations by demonstrating how detailed archival research can inform debates on CPA in other disciplines. A number of conclusions are suggested by our study.

In seeking to change legislation, the SWA operated as a conventional trade association to establish a common set of principles and practices akin to certification and self-regulation for the benefit of its members, mainly DCL, and the industry as a whole. However, pursuit of this objective was at the expense of firms whose competitive strategies diverged from the SWA-backed consensus. This was evident when William Walker’s bill, supported by the SWA, was enacted in 1988 (followed by the Scotch Whisky Order of 1990). A key element of this statute—prohibiting the sale of Scotch whisky that is lower than 40 percent abv.—effectively destroyed the under-strength section of the whisky industry and accentuated an intra-industry rivalry between key DCL firms and other large independent producers, such as William Grant.

We have argued that Scotch whisky does not fit a standard typology. It is not the trademark of any particular company, though many leading producers use this appellation, which was not recognized as such until 1989. Thus, unlike other famous appellations—Champagne, Cognac, Port—the development and growth of the Scotch whisky industry demonstrates how it is possible to create a world-renowned appellation without relying on the protection afforded registered trademarks. The rapid growth of the Scotch whisky industry during the period covered in this article was always threatened by quality debasement in export markets. Litigation, relying on the fundamental doctrine of consumer deception, and fighting passing-off were risky for the SWA because it had to prove that consumers understood Scotch whisky to mean whisky that was bottled, distilled, and matured in Scotland. Recognition of Scotch whisky as an appellation did not mean that this liquor was immune from misrepresentation. Nonetheless, since the European regulations came into force, the SWA has been named as a plaintiff in litigation involving Scotch whisky. It has been successful precisely because of the stronger legal definition of Scotch whisky afforded by these regulations.Footnote 158

The SWA’s nonmarket activity enabled it to capture the domestic political agenda to further the industry’s aims on the international stage. This duality in the realm of nonmarket strategy was inevitable because, although whisky and Scotch whisky are globally consumed, the latter is legitimately produced only in Scotland. Concurrent domestic and international activity is unusual for a trade association. Certainly, it does not conform to the “normal” evolution of the nonmarket strategies of trade associations that are hypothesized to progress from national to transnational activity.Footnote 159

Of course, the SWA was not always successful on the domestic or the international front. The UK government refused to engage in the defense of Scotch whisky interests in Italy and Spain in the late 1950s, and the early promise of negotiations at the Council of Europe never materialized. Nonetheless, the SWA’s intense lobbying has paid off. Regulatory alignment between the United Kingdom and the EEC was eventually secured in the late 1980s. The global profile of the Scotch whisky industry and its leading brands today is testament to the SWA’s success as a supra-national lobbying force.

Finally, although we attribute much to the skill and persistence of the SWA as an organization, the industry was primed for international success. It was an early adopter of brand marketing initiatives and packaging innovation. Indeed, the highly publicized debate about “what is Scotch whisky” surrounding the Royal Commission of 1909 led producers of blended Scotch, including John Walker, to create an “imagined past.” Dewar’s, for example, used the campaign “The Whisky of His Forefathers.”Footnote 160 The SWA also enjoyed the benefit of scalability due to the nature of the blending process.Footnote 161 In 1925, when DCL took control of Buchanan’s, Dewar’s, and Walker, “each of the constituent companies produced and distributed its own well-advertised brands.”Footnote 162 However, the industry, its firms, and their brands remained vulnerable to regulatory intervention and the lack of control over distribution. Overcoming these two key obstacles was necessary for the industry’s future and required a professional and powerful trade association. It took several decades for the major Scotch whisky firms to gain full control of their distribution networks. There was a long-established system of sole distributors in appointed geographic regions that were responsible for all marketing and promotional activity and pricing. This encouraged paralleling, prompting DCL, as the dominant firm, to withdraw Johnnie Walker Red Label from the United Kingdom in 1983 to stop it being paralleled into various European markets.Footnote 163 Guinness, as the owner of DCL, made significant mergers and acquisitions in the 1980s and focused on gaining control of distribution since 1986. Through full ownership or joint venture agreements, Guinness has secured approximately 85 percent of its overseas distribution.Footnote 164

We have benefitted from the particularly useful comments of the editor and referees. We also wish to record the help and support of Catherine Dale and colleagues (Law Library, Newcastle University), Paul Johnson (The National Archives), Christoph Malliet (Law librarian, KU Leuven Bibliotheken), Paul Duguid, Dev Gangjee, and the late Michael Moss.

Competing Interest

None