Words have power, and exposure to inclusive language has been shown to lead to more acceptance of marginalised groups in attitudes and actions (Tavits and Pérez Reference Tavits and Pérez2019). Gender-biased language is subtly ubiquitous in English and its roots are deep, so developing awareness of its consequences is the first step to addressing it. Building an understanding of the social and authoritative forces that guide language to be more inclusive can enable writers and editors to make conscious linguistic shifts to help equalise the status of women and nonbinary individuals through published words.

However, formal language usage rules have a centuries-long tradition of strict prescriptivism, from notable 18th-century grammarians Samuel Johnson (Dictionary of the English Language Reference Johnson, Young, Lynch, Dorner, Giroux, Mathes and Moreshead1755) and Robert Lowth (A Short Introduction to English Grammar Reference Lowth1762) to being embedded in modern style guides (see also Locher Reference Locher, Locher and Strässler2008; Curzan Reference Curzan2014). Prescriptivist traditions to label word forms as ‘right' or ‘wrong' and limit a constantly changing language can make it difficult for publishers and editors to use progressive and inclusive language in published writing even as cultural standards and informal registers begin to do so. One genre particularly influential in language change and standardisation is news media, which is widely accessible online and generally seen as a type of language authority (Ebner Reference Ebner2016). Given this position in society and related standards for consistency across different sources, journalists in the United States largely adhere to the language guidelines laid out by the Associated Press (AP).

Research Questions

One case of commonly prescribed language that discourages inclusion is the generic use of masculine nouns and pronouns. Though social and cultural trends in recent years have leaned in favour of gender-fair and -neutral language, formal language prescriptions tend to lag behind language trends, leading to possible conflicts between an editor's preferred usage and the prescribed forms. This led us to research the following questions:

1. How closely does actual usage in online written news align with AP's prescriptions on gender-specific language?

2. How has the actual usage of common gender-specific title variants in online written news content changed over recent years?

3. How has AP's stances on such terms evolved over the same years?

4. Do creators of published media tend to conform more to prescriptive guidelines or to diverge, possibly to reflect changing public attitudes?

5. Are guidelines for gender-specific titles becoming more inclusive? If so, do prescriptive guides introduce inclusive terms or adapt their guidance to keep up with popular usage?

Context: Language, gender, media, power

Written and published language is generally seen by default as carrying a level of prescriptive prestige and correctness (see Milroy and Milroy Reference Milroy and Milroy2012; Horobin Reference Horobin2018; Tieken–Boon van Ostade Reference Tieken–Boon van Ostade2019), and even unconscious consumption of the values implied in the words used in print can affect broader mental processes and social judgments. Many studies, for example, have shown that exposure to and use of masculine generic word forms contribute to sexist mental processes (see Friedrich and Heise Reference Friedrich and Heise2019, Lindqvist et al. Reference Lindqvist, Renström and Gustafsson Sendén2019; von der Malsburg et al. Reference Von der Malsburg, Poppels and Levy2020) and attitudes (see Matheson and Kristiansen Reference Matheson and Kristiansen2010; Patev et al. Reference Patev, Dunn, Hood and Barber2019; Tavits and Pérez Reference Tavits and Pérez2019). Hence, the approaches of language authorities have direct implications on the broader lives of language users.

The historical approach of prescriptivism in English, defined by Peters (Reference Peters2004) as the reaction to language change wherein one ‘may declare one particular form to be the right one to use,' is often contrasted with descriptivism, or when one ‘may simply remark on it without passing judgement' (p. 249). In language studies, strict prescriptivism is often viewed negatively; for example, McWhorter (Reference McWhorter1998) describes prescriptivism as having ‘spread linguistic insecurity like a plague among English speakers for centuries' (p. 65). This negative view has somewhat limited the number of studies of prescriptive effects on English language, but those studies that do exist on the effects of historic and modern prescriptivism often utilise corpora documenting the advice of prescriptive guides alongside contemporary usage. Studies on historic prescriptive grammars have demonstrated a less dramatic impact on actual usage than traditionally assumed (Auer and González–Díaz Reference Auer and González–Díaz2005; Yanez–Bouza Reference Yanez–Bouza2007), showing rather that grammars gradually changed to mirror naturally occurring usage trends (Anderwald Reference Anderwald2014). Corpus research on modern prescriptivism, however, gives evidence of steadier adherence by writers to prescribed forms, such as in the popular Chicago Manual of Style (Dant Reference Dant, Muhkerjee and Huber2012; Smith Reference Smith2019). Regardless of any patterns, the studies ‘can be interpreted as a warning against the danger of overestimating the explanatory potential of prescriptivism and a call for a more careful reanalysis of its impact in processes of language change in the history of English' (Auer and González–Díaz Reference Auer and González–Díaz2005, 336).

News media offers a unique sphere for this research, as a genre that ‘could reasonably be considered formal while still having widespread readership' (Smith Reference Smith2019, 38). Being a fact-based, informational style aimed at a general audience sets it apart from other edited genres with more leniency in language, such as fiction, as well as stricter or technical registers such as in academia. But just as the English language has been subject to fluctuating prescriptivist tendencies, so has news media traditionally valued principles of conscientious standardisation. This is done to avoid ‘problematic content of all kinds – gaps in the story, inaccurate information, confusion, contradictions, potentially libelous material, and' – as Bell put it in Reference Bell1991 – ‘the various kinds of nonsense which a reporter may commit to paper' (p. 75). When deciding which prescriptive rules to enforce and how to address other usage quandaries that arise, Bell noted three kinds of language standards: ‘the wider speech community's rules of the language's syntax, lexicon, spelling, and pronunciation; general guidelines on writing news; and the “house style” of the particular news outlet. These standards may be overtly prescribed, unwritten or unconscious' (p. 82). Modern news writing has retained a balance of common actual usage, widespread (usually prescriptive) tenets from guides, and publisher-specific exceptions.

The most widespread and extensive news-writing style guide is AP (Associated Press), whose reach has grown since 1846 to become today's golden standard in its discipline in the United States. AP is self-described as ‘the definitive resource' for journalists, students, and corporations worldwide for providing ‘guidelines for spelling, language, punctuation, usage and journalistic style' (AP 2022). Indeed, it is widely acknowledged by other guides that ‘although some publications such as the New York Times have developed their own style guidelines, a basic knowledge of AP style is considered essential to those who want to work in print journalism' (Purdue OWL n.d.). For example, NPR's style guide states, ‘the Associated Press Stylebook is the basis for many of the guidelines that appear here'; Buzzfeed's outlines that ‘the preferred style manual is the AP Stylebook,' even that ‘generally, AP Style trumps [Merriam–Webster]' for debated spellings.

News organisations with such authority also carry a reputation of officiality that can extend to a user perception as upholders of set language standards, with ‘correct' language associated with ‘journalistic credibility ‘(Ebner Reference Ebner2016, 308). This careful attention to language must also balance with the need for editors and writers to be alert to innovation, as ‘news almost by definition concerns itself with changes and ideas, and an editor unfamiliar with or uninterested in them becomes ineffective' (Gilmore and Root Reference Gilmore and Root1976, 20). In occupying this unique cultural space, news writing is ideal for corpus-based prescriptivism vs. usage research for its wide accessibility to readers and researchers, its supposed adherence to moderately strict prescriptive precedents and guidelines, and its authoritative image in the view of the general public.

The wide distribution and readership of online news and the public's attitude toward the language used in that medium mean that the language of news media can both inform of facts and subtly influence readers’ social attitudes. The key role of news and media in language standardisation – and conversely, liberalisation – has been long acknowledged (Noss Reference Noss1967), and recently illustrated in a unique linguistic opportunity. Gustafsson Sendén, Bäck, and Lindqvist (Reference Gustafsson Sendén, Bäck and Lindqvist2015) administered surveys over four years to gauge real-world impacts when the Swedish government sanctioned hen as a generic and transgender/nonbinary pronoun, concluding that ‘new words challenging the binary gender system evoke hostile and negative reactions, but also that attitudes can normalise rather quickly' (p. 1; emphasis added), with time being the most influential factor in positive attitude change. Further, the new neutral word's early adoption by popular magazines and then newspapers is thought to have improved its standing more than arguments from linguistic and feminist sources did, the researchers state. This insight, along with findings by Sczesny et al. (Reference Sczesny, Moser and Wood2015) that revealed gender-fair language implementation can be predicted by habitual use, give positive signs that repeated exposure can lead to lasting language change. As different institutions, including the news media, prescribe gender-fair language – or at least not proscribe it – and normalise such usage, there is possibility for more wide-ranging linguistic and cultural patterns to emerge that can positively impact a society's collective attitudes toward different genders.

Methodology

To gain insight into the relationship between prescription and usage of gender-specific terms in online news, it is important to have evidence of both changing prescriptive guidelines and actual published usage that can be evaluated en masse. We have chosen to extract data from specialised corpora, or online collections of published works that allow users to search for words or phrases in context within the entire collection.

To measure the changing prescriptions in AP style, we created our own small corpus by compiling AP's entries on our search terms from 2011, 2013, 2017, 2019, and (February) 2022. To measure actual usage trends in news published online, we used the News on the Web (NOW) corpus, which has data consisting of over ten billion words and adds more daily. To narrow the search results from this massive corpus for each search term, we filtered the results to a range of 2010–2021 (the most recent full year at time of data collection), included plural and singular forms, and chose a display showing frequency of occurrences per million per year.

To focus our research, we chose the following gender-specific title roots and variants to examine: spokes[man, -woman, -person], chair[man, -woman, -person], [member of] congress[man, -woman, -person], business[man, -woman, -person, owner], and council[man, -woman, -person, member]. We selected these five word families to act as a small case study on the state of prescriptivism versus usage within gendered language based on their presence in previous literature examining gender-fair gaps in AP (McClellan Reference McClellan1994) and their specific inclusion in 2010–22 AP Stylebooks. Further, a search for the most frequent -woman words in NOW (‘*WOMAN_nn': * for wildcard text preceding ‘women'; _nn for nouns; capitalisation for lemmas) returned business-, chair-, congress-, council-, and spokes-based titles as most frequent, affirming their ongoing relevance (see Figure 1). Based on the combination of the presence of AP guidelines on these specific words and the words’ relevancy in older studies and current data, the selection of these key variants is justified as a subject of further research, even as we acknowledge that our data-driven selection of terms in each word family do not necessarily encompass direct synonyms nor the full list of possible alternatives.

Figure 1. Frequency list results in NOW corpus for ‘*WOMAN_nn'.

We also recognise that myriad external, cultural factors outside of language guidance will influence the fluctuation of words over time, though they are not explored in depth in this study. The present research merely examines recorded usage to view against prescriptive guides for illustrative rather than explanatory purposes.

Results

After collecting data from both AP and NOW and compiling relevant information in different charts and tables for easy analysis, we examined each word family's variants compared to each other and compared to AP's guidelines on such over time, as well as general patterns and trends from looking at the overall spread of AP and NOW data. Page numbers are not cited for AP Stylebooks as they are alphabetical entries and easily findable from that metric.

Generalised entries in AP

Before examining the five word families of gendered titles in AP and NOW, there are two generalised entries in the 2011–19 print AP Stylebook editions that are telling of AP's overarching patterns and approaches to gender-specific language: ‘woman, women' entries and ‘-person' entries. Key parts of the entry for ‘women’ in 2011 and 2013 are as follows:

Women should receive the same treatment as men in all areas of coverage. Physical descriptions, sexist references, demeaning stereotypes and condescending phrases should not be used. To cite some examples, this means that:

– Copy should not assume maleness when both sexes are involved, as in Jackson told the newsmen or in the taxpayer . . . he when it can be said Jackson told the reporters or taxpayers . . . they . . .

In other words, treatment of the sexes should be evenhanded and free of assumptions and stereotypes. This does not mean that valid and acceptable words such as mankind or humanity cannot be used. They are proper.

The entry for ‘woman, women' in 2017 and 2019 is a shorter version of what is found in 2011 and 2013: ‘Treatment of the sexes should be evenhanded and free of assumptions and stereotypes. This does not mean that valid and acceptable words such as mankind or humanity cannot be used. They are proper.' The online entry for ‘woman, women’ in February 2022 is an even shorter version, with a link to a more comprehensive ‘gender-neutral language’ entry: ‘Treatment of the sexes should be evenhanded and free of assumptions and stereotypes.’

The progression shows not a change of content but a shortening of it. Rather than being evidence of waning interest in gender parity in language, however, this shortening to a simple statement against stereotypes could reflect a broader cultural consciousness that has become more gender-aware over the last decade (see Minkin and Brown Reference Minkin and Brown2021; Wilson and Meyer Reference Wilson and Meyer2021). Explicit reminders of gender-fair principles may be seen as redundant, as more people believe that female and nonbinary individuals should not be treated differently in text from their traditionally dominant male counterparts (see Johnson and Subasic Reference Johnson and Subasic2011).

AP Entry Results

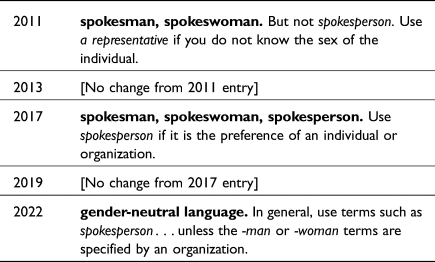

Text from the relevant word-specific entries in the AP Stylebook 2011, 2013, 2017, 2019 (in print) and February 2022 (online) is found in Tables 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, and 1.6.

Table 1.1. Entries on -person

Table 1.2. Entries on business-based title variants

Table 1.3. Entries on chair-based title variants

Table 1.4. Entries on congress-based title variants

Table 1.5. Entries on council-based title variants

Table 1.6. Entries on spokes-based title variants

NOW results

Because the total number of sources NOW pulled from fluctuated over the years and with it the total number of words in the corpus, the results have been normalised and presented comparatively against each other per year. For exact data on the size of the corpus each year and each word's frequency per million per year, see Appendix A. For the exact data (in count and percentage) for all word sets, see Appendix B.

As noted in Figure 2, the traditionally prescribed male-exclusive form of businessman held dominance over other variants for much of this time frame. However, the main contender, the neutral form of business owner, made steady gains in each year from 2015 onward until its frequency jumped as businessman's dropped in 2020, and business owner became the most common form of this title continuing through 2021 in a clear trade-off. Regarding the less-popular variants, businesswoman and businessperson frequency counts each increased with the influx of news content in each year but were never significant enough to see a rise in prevalence.

Figure 2. Relative frequency per million of business-based title variants in NOW.

When considering chairman, chairwoman, and chairperson in NOW (see Figure 3), chairman is the clearly dominant form, showing up significantly more frequently than the other two options’ frequencies per million combined, even as its percentage dips mildly with subtle gains by chairperson in the latter two years surveyed. The neutral chairperson variant, like in the trends for businessperson, never seems to have caught on as a neutral option but still remains slightly more prevalent than the feminised chairwoman variant. It is, however, not unlikely that, as also in the business-based example, an alternate neutral is being increasingly used in news writing; here, namely the unmeasured chair was not searched for due to being unable to separate the more common use of chair as in the furniture within corpus results.

Figure 3. Relative frequency per million of chair-based title variants in NOW.

The results for congress- are like in the business-based word family: there is a noticeable tradeoff where the once-dominant masculine form, congressman, dips in prominence in the latter two years of this search (see Figure 4). It is just barely overtaken in frequency per million by another steadily gaining multi-word neutral term, member of congress. Also mirroring the previous word families’ trends, the relative frequency of congresswoman sees increases over the years but is always behind congress member. The -person variant seems very seldom used, barely even registering more than a few counts per million words at its peak in 2021.

Figure 4. Relative frequency per million of congress-based title variants in NOW.

The council-based titles in its word family include two gender-specific and three neutral variants surveyed in NOW. The results for this grouping, shown in Figure 5, are also unique from the others with the most frequent variant being not the -man form but council member – and the next closest (though by varying margins) for every year but one is councilor, another neutral term (in 2020, councilman's frequency edged out councilor's by a small margin). The councilman variant is steady as the next most-frequent variant, but its prevalence dips over time as councilwoman, the next closest (if not close) variant, gains more usage, seemingly at the cost of councilman. Councilperson is largely neglected (its lowest frequency is .05 occurrences per million words and highest 1.47 occurrences, compared with the next closest councilwoman's range of 2.13 to 78.81 per million) and makes a negligible showing.

Figure 5. Relative Frequency per Million of Council-Based Title Variants in NOW.

The results of the last search, as detailed in Figure 6, offer a telling picture with a clear pattern similar to the tradeoff observed in the business- and congress-based title variants though with key differences in the variant types themselves. While spokesman remains solidly as the most frequent variant through 2017, the initially less-frequent neutral spokesperson makes steady gains in frequency from 2016 on and nearly matches the levels of spokesman in 2018. As early as 2019, this neutral variant has overtaken spokesman and continues to climb as the masculine variant decreases in prominence. The last variant, spokeswoman, never challenges the other two variants’ comparative dominance but does see increased usage as years go by until 2021, when spokesperson takes some of spokeswoman's stake.

Figure 6. Relative frequency per million of spokes-based title variants in NOW.

Discussion of AP standards vs. NOW usage

After evaluating the results of the NOW corpus, word families expressed a pattern of either a dominant male-gendered form being replaced by a neutral form or a single term maintaining dominance throughout. In many of these cases, overlaying AP's progressing guidance in the same period reveals various points of connection or contention.

Primary trend: -man gives way to a neutral

In three of the word families, an initial run of -man forms as the dominant option were rapidly replaced by a neutral form in the years leading up to 2021: businessman for business owner, congressman for congress member, and spokesman for spokesperson.

Though AP editions in this timeframe had little specific information on business-based titles, some relationships can be discerned based on the general principles in 2011–19 entries. The low representation of businessperson aligns with 2011 and 2013 prescriptions against -person forms (see Table 1). But when AP started allowing for more gender-neutral language sometime by the 2017 edition whenever it is ‘preferred by an individual' or ‘organisation' (see entries on ‘-person', ‘chairman, chairwoman', ‘spokesman, spokeswoman, spokesperson'), rather than spiking as a preferred term, -person remained stagnant. At this same time, however, a different (and perhaps less awkward) two-word neutral variant in the form of business owner started to make gains, eventually leading to its standing as the most frequently used variant per million in 2020 (50.3% relative frequency). In this vein, it is also notable that business owner entered alongside businessperson as the allowable terms by the February 2022 online version of AP.

Despite the steady rise of member of congress through the decade surveyed, AP did not seem to take common usage into account in the 2011–19 guides. One possible accounting for the stricter hold on the gender-specific congressman and congresswoman could be due to the legal nature and common context of the words, with legal wording tending to be more careful and precise than other registers of language. It could also be due to the common use of congresswoman and -man as official, capitalised titles in front of individuals’ names. This can be seen in the February 2022 entry's statement that even with the formal endorsement of a bevy of neutral alternatives, AP still lists congressman and congresswoman as ‘acceptable because of their common use.' This is similar logic as was used in the 2022 statement about chairperson and spokesperson being accepted due to common use but in the opposite direction – where those examples were changed in favour of common usage of neutral forms, this instance with congresswoman and -man is unchanged due to common usage of the gender-specific terms. As a final note, here as with all other word sets, there are ways to structure sentences to avoid the use of noun titles (e.g., ‘X, who represents Y’), and while outside the present scope, such constructions should be acknowledged as a possible factor of title-based usage shifts.

The initial entry for the spokes- family in 2011 and again in 2013 is already more neutral-friendly than many others, stating to ‘use a representative if you do not know the sex of the individual' rather than implying a default to the male-specific form. But this addressing of unknown gender is only one aspect of the masculine generic; it does not address what form to use if the word is used for mixed-gender groups, for the general term, or for nonbinary individuals. Similarly in 2017, although the neutral is listed with the other forms, it is implied that spokesperson should be confined to situations when ‘it is the preference of an individual or organisation,' as opposed to general or neutral use. Despite the slow uptake on spokesperson in the stylebooks, however, popular usage is shown to be in favour of the form a while before AP formally endorses it, first overtaking spokesman (42.9%) in 2019 with 43.5% of relative usage. Also unique in this word family, the dominant form is the -person structure that is disfavored in the other examined word families, where function-based neutral titles prevail. This is possibly because, as the only neutral option presented, the neutral ‘vote' of usage is not split between variants (while still noting the exclusion of terms ineligible for the present corpus bounds, such as ‘representative').

Secondary trend: Single dominant word forms

In the other two word families, one sees a gender-specific form as the dominant throughout the period sampled – chairman – while the other shows a gender-neutral form as the most used option throughout – council member. This term maintains a minimum 43% relative frequency in 2013 up to 52% in 2020.

The AP entries for chair-based title variants reflect the previously seen patterns of a gradual evolution from prescribing gender-specific terms to allowing some neutral forms to recommending neutral forms. Despite this pattern in AP guidance, however, the NOW results do not reflect as dramatic a shift in gender-neutral usage for chair-based variants. This could, it must be stressed, be due to the omission in our search results for the neutral title chair due to the many other general uses of the noun chair. Another consideration in interpreting the dominance of chairman in this case is the combination of male-dominated demographics in business and leadership fields (World Economic Forum 2022, 36) and the deep roots of the masculine generic; even as masculine generic trends wane, the high prevalence of -man variants then likely comes from specific references to individual men and possibly also a lingering assumption or habit of referring to ‘chairmen'. We also see from the other word families a general lack of uptake for -person as a neutral form, which could be due to factors such as phonetic ease of pronunciation or a cultural sense of sounding forced in an effort to be neutral.

Although AP only endorses the terms councilor, councilman, and councilwoman through the entirety of the timeframe searched in NOW, it is the unmentioned council member that steadily increases its dominance over the other variants year by year. Added by the February 2022 online edition, this new guidance seems to be following the lead of popular educated usage. However, such a reasoning cannot be made for the other neutral term endorsed by AP in 2022 – councilperson remains comparatively underused on its own and is especially unpopular when compared to all the other variants. This also seems to perpetuate the pattern found in previous word families that when other, more function-based neutral options are presented, -person variants are the less popular option.

Conclusion

The aim of this research was to begin investigating the impactive intersections of linguistic prescriptivism, gender-specific language, and the medium of online news media to gain insight into how these different forces have evolved over the past decade in relation to each other. Our research is not meant to be a comprehensive investigation nor to draw definitive conclusions on the relationship of prescriptive guides and actual usage or the state of gender-fair language as a whole. Rather, through a small-scale study looking at a specific set of titular terms over two decades, this research adds insight to an ongoing conversation in linguistic, literary, and editorial spheres and illuminates avenues of future complementary research.

With a focus on five traditionally gender-specific titles, our comparative look at the changing guidelines of the Associated Press Stylebook and the usage of different variants on such titles (as documented by the NOW corpus) has illuminated patterns of progressive change on both fronts. The overall trends in the AP guidelines when it comes to gender-specific titles – namely business-, chair-, congress-, council-, and spokes-based variants – in published stylebooks in 2011, 2013, 2017, 2019, and February 2022 illustrate a clear progression toward inclusive and neutral language. As seen in the search results from the NOW corpus, actual usage in online written news sources has also progressed steadily to more neutral and inclusive title variants through the years. While the results of the majority of word families surveyed indicate almost exclusive use of -man forms the early years of the time bounds, most end in the latter years of the timeframe with a neutral variant as the most frequently cited per million words. For specific neutral variants, the -person forms were not nearly as frequently used in a word family when other, function-forward neutral word forms (e.g., council member or business owner) were options. While -person variants did generally increase in usage over time, the alternate neutral title variants were the ones that increased in usage more rapidly and eventually overtook the -man forms. Though the -woman variant for each word family saw an increasing yearly frequency, in no case was this form ever dominant.

Taken together, a comparison of the trends in prescriptions in AP style and in usage as documented by NOW shows that both language authorities and language users are trending toward gender-neutral titles, though perhaps at different rates. Based on the consulted editions, AP did not fully support neutral variants as preferred forms until after their 2019 edition, which is after the timeframe searched in NOW. Despite not having the official sanction, however, usage of neutral forms surged in the mid-2010s. Even though not the preferred forms in AP in 2017 and 2019, it could be that even a mild statement on the acceptability of the neutral forms was enough for more writers and editors to begin using them in place of -man and -woman forms.

By looking at these results within the foundational body of literature evaluating prescriptive traditions via large online corpora, it is clear that the relationship between English language authorities and English language users is more complex than has been historically assumed. However, it is hard to discern a definitive answer from this type of study as to the exact relationship or correlation between these two sides of a language relationship. Even as telling patterns have emerged illuminating the power and influence of the everyday language user, ‘the interaction of prescriptivism and usage defies straightforward cause–effect relationships’ (Curzan Reference Curzan2014, 84). One would be hard-pressed to prove that modern prescriptive rules cause changes in language, though this study adds to other research on rules and changes in usage that make it clear prescriptivism is at least a factor of language change.

Further, while helpful in discerning patterns and correlations, corpus analyses alone cannot reveal the exact amount that prescriptive rules factor into language change. So while this study is not broad enough to make any definitive claims on leader-follower dynamics, it does appear that writers and editors have adhered to AP increasingly less when it comes to inclusive and gender-neutral terms, perhaps rather opting to follow their own judgement or principles. AP, on the other hand, appears to see and respond to changing adherences and cultural values after shifts take place in the culture, as evidenced through written online news media.

One gap in existing gendered language research is acknowledgement and participation of nonbinary individuals, almost all studies operating under the male-female binary and not considering the effects on people outside of that dichotomy. While the limits of this study preclude critical analysis of nonbinary and transgender implications within the chosen word forms, this area can be acknowledged as a potential academic precursor and social beneficiary of the present study. A hopeful note for this area of awareness is also found in the 2022 ‘gender-neutral language' AP entry, which specifies to ‘use terms for jobs and roles that can apply to any gender' to be ‘inclusive of people whose gender identity is not strictly male or female.'

On an ideological level, this research has exposed the nuances and complexities in the relationship between those who create prescriptive guidelines and the writers and editors who are asked to apply them. Every evidence that proves how usage guides do not have complete authority, that language mandates that once went unquestioned are not usually so settled as to be past questioning, is something editors and writers should bear in mind. While prescriptive guides can be a good place to start to learn the basics, newcomers in communication and publishing fields should realise that they are not in a completely deferential position to one or another language authority. As Owen stated, ‘Editors . . . do not see themselves as creators of hyperstandard rules whose enforcement ensures their own job security; they simply see themselves as correctors of errors, making texts clear, correct and consistent' (p. 293). This study illustrates patterns of deviance from stated AP guidelines in the name of inclusivity, with many writers and editors doing what they must to make texts culturally ‘clear, correct and consistent', even if that means using progressive language not currently sanctioned by relevant language authorities. Knowledge of this two-way relationship should empower editors and writers to feel comfortable enough with general principles and guidelines to consciously bend specific rules when it comes to meaningful language choices, as with gender.

When it comes to consumers of news and English users in general, the trends identified in this study bode well for inclusion of individuals regardless of their gender, disassociating titles with gender biases and stereotypes. As this trend continues in both advisory and actual channels, the power of the media could help turn English users’ mental defaults away from the masculine in more areas than just titles, including in overall language usage and from there attitudes and cognitive patterns. Even seemingly small details like using neutral forms in titles regardless of the context can lead those creating and editing content to incorporate principles of neutrality and inclusiveness in many other areas.

While this study is not definitive, it reinforces the patterns identified in other studies that usage authorities’ prescriptions follow actual usage trends more than the other way around, especially in the complex dynamic of culturally significant and identity-driven language. However, language authorities’ sanctions are not to be discounted, as the trends seen here suggest that endorsements of new popular forms made by respected stylebooks can help tip the scale in neutrality's favour for those editors and writers who are stricter in adhering to official guidance. With knowledge of the flexible nature of authoritative usage guides and strong precedents for letting cultural trends influence language change, those involved in writing, editing, and publishing can make more consciously inclusive choices in their written language in ways that positively affect consumers of news and other written media.

Appendix A. Number of words in NOW corpus per year

Appendix B. Frequency per million of gender-based title variants in NOW

Frequency per million of business-based title variants in NOW, with percentage share per year

Frequency per million of chair-based title variants in NOW, with percentage share per year

Frequency per million of congress-based title variants in NOW, with percentage share per year

Frequency per million of council-based title variants in NOW, with percentage share per year

Frequency per million of spokes-based title variants in NOW, with percentage share per year

BROOKE JAMES (she/her) graduated with an MA in Publishing Media from Oxford Brookes University in 2023 and a BA in Editing & Publishing (minor in Digital Humanities & Technology) from Brigham Young University in 2022. Her main research interests center on gender-fair language and the role of editorial processes in historical and modern publishing. Brooke now works as an assistant editor for higher education materials at Oxford University Press in Oxford, UK. Email: [email protected]

BROOKE JAMES (she/her) graduated with an MA in Publishing Media from Oxford Brookes University in 2023 and a BA in Editing & Publishing (minor in Digital Humanities & Technology) from Brigham Young University in 2022. Her main research interests center on gender-fair language and the role of editorial processes in historical and modern publishing. Brooke now works as an assistant editor for higher education materials at Oxford University Press in Oxford, UK. Email: [email protected]

JACOB D. RAWLINS (he/him) is an associate professor in the Linguistics Department at Brigham Young University, where he teaches courses in editing, publishing, and grammar. He earned his PhD in Rhetoric and Professional Communication from Iowa State University. His research interests include applied rhetoric, linguistic prescriptivism, the history of the book, and professional communication. Email: [email protected]

JACOB D. RAWLINS (he/him) is an associate professor in the Linguistics Department at Brigham Young University, where he teaches courses in editing, publishing, and grammar. He earned his PhD in Rhetoric and Professional Communication from Iowa State University. His research interests include applied rhetoric, linguistic prescriptivism, the history of the book, and professional communication. Email: [email protected]