Introduction

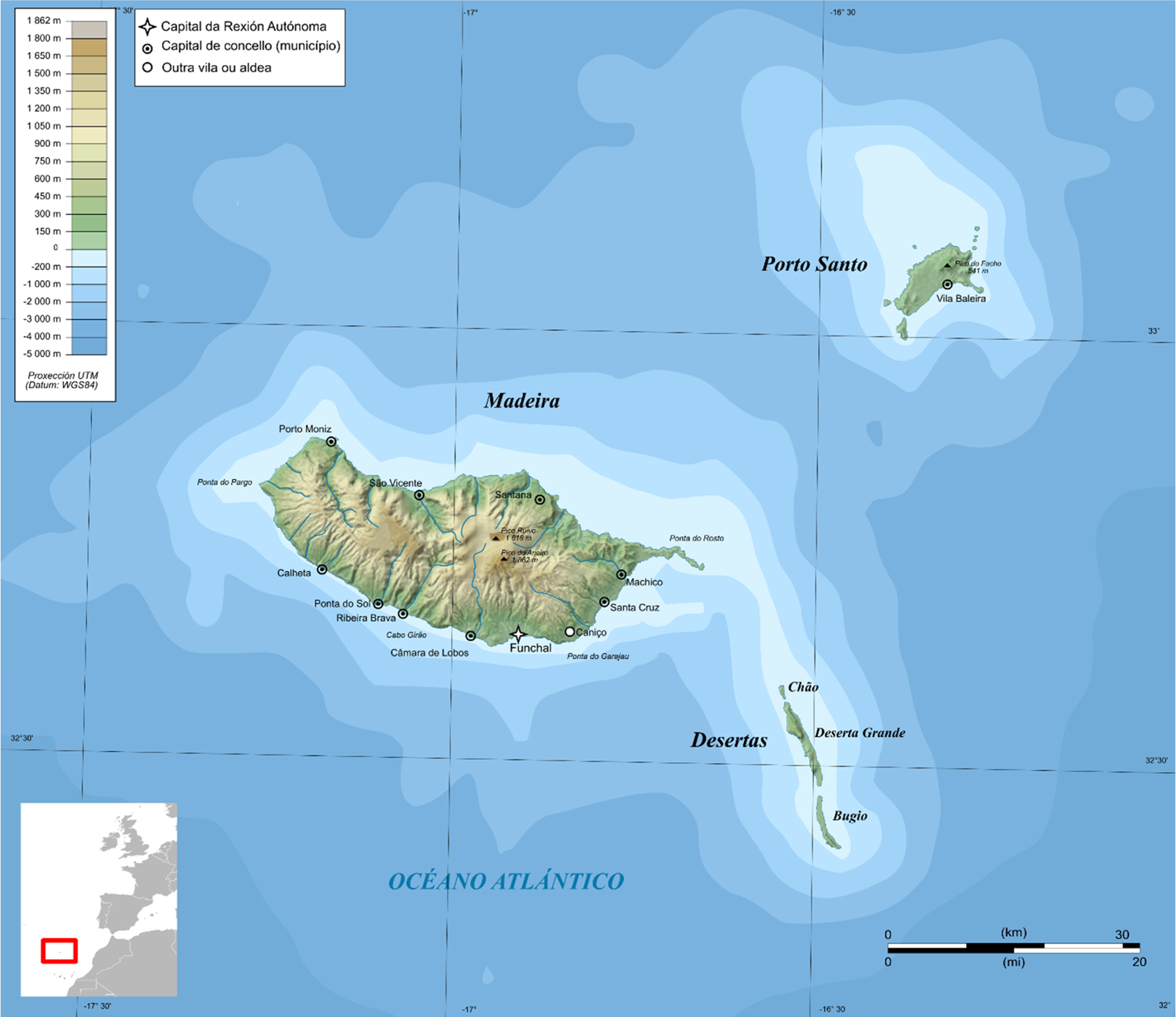

‘Lesser-known varieties of English’ (Schreier, Reference Schreier2009; Schreier et al., Reference Schreier, Trudgill, Schneider and Williams2010) have received increasing attention in the last decade.Footnote 1 In particular, Englishes on islands with historical and political ties to the United Kingdom or the United States have been described, such as the varieties in Bermuda (Eberle, Reference Eberle2021), Samoa (Biewer, Reference Biewer2020), and Tristan da Cunha (Schreier, Reference Schreier2009). However, Madeira has hitherto received extraordinarily little attention, although it used to be home to a small but enormously influential group of British expatriates who controlled large parts of the economy and owned a considerable amount of land on the island. Even today, approximately 1,000 emigrants from the United Kingdom live permanently in Madeira, which constitutes the second largest group of foreign residents (DREM, 2020b: 11). ‘Madeira’ refers to both a Portuguese archipelago and this archipelago's main island located ca. 737 km west of Morocco's coast (see Figure 1). Overall, Madeira had a population of 267,785 in the last official census from 2011 and is a highly popular tourist destination, with roughly 8 million overnight stays by visitors in 2019 (DREM, 2020a).

Figure 1. Topographic map of Madeira including its location relative to Europe and West AfricaFootnote 2

Apart from its mountainous beauty, Madeira also has complex relations to England and the English language. Even though the island has never been an official colony of the British empire, it was occupied by British troops twice, played an important role in British trade and tourism, and achieved quasi-colonial status between the 15th and 19th centuries. In fact, although the British population always remained small, it was highly influential to the extent that Madeira was described as ‘largely anglicised’ in 1873 (Elucidário Madeirense, 1921, qtd. in Gregory, Reference Gregory1988: 22). Linguistically, this puts Madeira in a truly special position: While it always remained under Portuguese rule, the sociolinguistic conditions on the island strongly resembled that of postcolonial contexts (cf. Buschfeld & Kautzsch, Reference Buschfeld and Kautzsch2017: 110–111; Schneider, Reference Schneider2007: 33–37) in that English was brought to the island by a small but powerful group of settlers who, at least to some extent, were determined to stay for good while still maintaining close ties with their British mother country. Today, English has become indispensable as the language of tourism, the dominant economic factor on the island. In touristic contexts it functions as a Lingua Franca and is constantly in contact not only with Portuguese but also with the tourists’ languages. In this first study of English in Madeira with a World Englishes focus, we provide an overview of the variety by briefly discussing its history, its importance in the tourism sector, some linguistic features identified in a small corpus of Madeiran Airbnb entries, and the theoretical framing of English in Madeira.

The History of English in Madeira

One of the potential reasons for the lack of attention that has been given to Madeira in the World Englishes context is that it has never been an official British colony. Nevertheless, the island was of economic and strategic importance for the British Empire: Its position on the route to colonies and trading points such as India, America, or the West Indies made it a central port of call for both the navy and merchant vessels (Gregory, Reference Gregory1988: 15). In the 15th and 16th centuries, British merchants also started to set up their own trading firms on Madeira. While they first focused on sugar plantations, this was soon replaced by wine trade. Madeiran wine was highly popular in 17th- and 18th-century Britain as well as in British colonies overseas, and its trade was promoted by special agreements with the Portuguese government (Disney, Reference Disney2009: 90; Gregory, Reference Gregory1988: 25–27). As the merchants also brought their families to settle on the island, Madeira soon had a small but powerful group of British residents who considerably influenced its economic and socio-cultural landscape. They opened schools, set up churches and cemeteries, and invested in different industries (e.g., tourism, furniture, rope making, embroidery, etc.) (for an overview see Gregory, Reference Gregory1988).

When the Portuguese government had to face a potential French invasion and hence the loss of its provinces in the early 19th century, Britain was therefore in danger of not only losing her safe access to India but also her control over Madeira as such. The British government reacted by occupying the island twice (first, from 1801 to 1802, then from 1807 to 1814) (Disney, Reference Disney2009: 293; Gregory, Reference Gregory1988: 47–51, 64). Both these occupations were temporarily restricted and sanctioned by the Portuguese government (albeit under enormous external pressure), but they still show the significance the island had for Britain, if only as an important stronghold against the French. Nevertheless, what made Madeira a quasi-British colony was certainly not the military presence but rather the pervasive and continual economic influence British expatriates exerted. While this started with sugar and wine trade, tourism soon became a central source of income for both Madeirans and British citizens living on the island.

Tourism in Madeira

Consequently, the most important function of English in Madeira today is as the language of tourism interactions. Tourism in Madeira began as early as the 15th century, with a shift from initial ‘colonial tourism’ to ‘therapeutic tourism’ in the 19th and 20th centuries (Rodrigues, Reference Rodrigues2019: 348). The island was advertised as a health resort whose climate was thought to have positive effects on pulmonic diseases such as consumption (Rodrigues, Reference Rodrigues2019: 355). A key factor in the upsurge of Madeira's tourism was the invention of the steamship and Madeira's growing reputation as a beautiful destination, with ‘English people of the leisured class [becoming] increasingly attracted to the island because of its mild climate and lovely scenery’ (Minchinton, Reference Minchinton1990: 517). These developments led to a considerable increase in the amount of both short- and long-term visitors – while approximately 80 touristic visitors were reported in 1834, the number of (health) tourists had more than tripled three years later (Cooper, Reference Cooper1840: 24; Driver, Reference Driver1838: iii). These visitors typically stayed for several weeks or even months to avoid the English winter or be cured of tuberculosis (Gregory, Reference Gregory1988: 110). Even nowadays, visitors from English-speaking countries (Ireland, the UK, Canada, and the US) constitute the largest group of all non-Portuguese tourists (DREM, 2021b: 22).Footnote 3 Even though tourists today tend to come for shorter stays rather than spend the winter on the island (Almeida, Machado & Xu, Reference Almeida, Machado and Xu2021: 3), we can therefore assume that English retains its central function as the language of tourism in Madeira.

The observation that at least a functional command of English is acquired by people working in the tourism sector in countries where other languages are spoken more widely has been noted by Schneider (Reference Schneider2016), who refers to the resulting varieties as ‘grassroots Englishes’. For the case of Madeira, we propose that the term applies individually but not societally. Madeirans begin to learn English at the age of 6 (or, optionally, as early as age 3; Ferreira, Freitas & Carvalho, Reference Ferreira, Freitas and Carvalho2009) and, accordingly, develop at least some English language skills. The early acquisition of English is one of the potential reasons for Portugal placing seventh out of 100 countries ranked in the EF English Proficiency Index (EF Education First, 2020). Some degrees at the University of Madeira (UMa) are offered in English and there are English-language and Portuguese-English bilingual schools, such as The International School of Madeira and the International Sharing School. In addition, there are numerous blogs and news websites published in English (e.g., Madeira Web, Madeira Island News, and the Madeira Island News Blog).Footnote 4 Reports on tourism websites such as TripAdvisorFootnote 5 indicate that, unexpectedly for a typical grassroots setting, staff at restaurants, hotels, and so forth have a good or even excellent command of English. Although these claims require corroboration, the impression is that English is widely spoken in Madeira – at least in touristic contexts. Another valuable addition would be a linguistic landscapes study in order to make informed statements about the presence of English in the Madeiran public sphere.

Data

To gain a first glimpse into the variety of English spoken in Madeira, we built a small corpus of written English-language internet texts produced by Madeirans for whom English is likely a second or foreign language. Finding a suitable corpus database proved to be a challenging task, as (a) there are no online English-language newspapers for Madeira which are written primarily by native Madeirans and (b) a wide variety of English-language blog entries by Madeirans is difficult to come by. The same applies to spoken data such as interviews, vlogs, etc. For these reasons as well as the importance of the tourism sector, we chose to use online accommodation listings as our primary database.

As the hotel industry frequently employs either native or very fluent speakers of English for the curation of their online presence, a decision was made to focus on a more ‘grassroots’ source, namely Airbnb. Airbnb is a vacation rental company which functions as an intermediary between (mostly local) hosts (people owning a property which they want to rent out for a certain period of time) and (mostly foreign) visitors who are looking for a more ‘authentic’ type of accommodation, such as a cottage or an apartment, as opposed to a hotel. On Airbnb, most hosts are regular people who frequently describe themselves in as much detail as they do their property in order to appear more authentic and trustworthy to potential guests. For the purposes of our corpus, this feature is helpful as it allows us to better ‘vet’ the authors of our data as either (native) Madeiran or not. We only included hosts whose names and biographies hinted at a Madeiran or, at least, a Portuguese background.Footnote 6

Due to the (as of yet) relative scarcity of Airbnb accommodation listings on the Madeira archipelago, the data collection process could be done entirely by hand. Ultimately, two categories of listings were downloaded: accommodations (for the islands of Madeira and Porto Santo) and experiences (advertisements for guided events such as car and bicycle tours, trail runs, and pub crawls).

The ‘accommodations’ part of the corpus consists of 177 entries from 148 different hosts and a total of 41,452 words. Of the 148 hosts, 61 are women, 71 are men, eight are mixed-gender couples and in eight cases the gender was unknown, either because the name of the accommodation had been indicated instead of the host's name or because the accommodation belongs to a small, family-owned company. Most entries in the ‘accommodations’ subcorpus have a tripartite structure, containing a description of the property, a description of the location, and brief autobiographical information about the host, although the latter two sections were not available for some of the entries. The ‘experiences’ part consists of 45 entries from 20 unique hosts, of which two are women and 18 are men, adding up to 11,642 words. This subcorpus is likewise tripartite in structure in most of the cases, consisting of a description of the advertised experience, a description of the location, and some autobiographical details about the guide. In total, the corpus is 53,094 words in length. Furthermore, for ease of cross-reference, each corpus entry was assigned a unique ID.Footnote 7 Personal names and other identifying information have been changed for data protection reasons.

Some features of English in Madeira

The following overview gives a general idea of some recurring features we identified in the corpus. Since our data comes from a corpus of written language, we mostly focus on lexis, morphosyntax, and spelling, but we point out potential phonological transfer from Portuguese for the feature of /h/ deletion.Footnote 8 The relevant parts in the corpus examples are highlighted in bold and we added the symbol for ‘zero’ where applicable.

(a) Pro-drop/minus-subject or minus-object

(1) ‘I am always willing to work with my clients so that in this way ∅ have a peaceful stay’ (M-AC:026)

(2) ‘∅ Am a reading monster [ . . . ]’ (M-AC:061)

(3) ‘∅ Is well equipped with refrigerator, washer, hob, oven, microwave, coffee machine and other utensils [. . .]’ (M-AC:022)

Some examples from the Airbnb corpus, such as (1) to (3) printed above, suggest the existence of pro-drop properties, in particular the ellipsis of subject and object pronouns. Subject pro-drops can be found in several varieties of English (eWAVE, Kortmann et al., Reference Kortmann, Lunkenheimer and Ehret2020, feature no. 43) and transfer from the L1 is often a promising explanation. Hutchinson and Lloyd (Reference Hutchinson and Lloyd2003: 44; emphasis removed) point out that sentences such as ‘(tu) Vens ao cinema? Are you coming to the cinema?’ and ‘(nós) Estávamos à tua espera. We were waiting for you’ are typical in European Portuguese and that the subject is regularly omitted, since the verb carries the relevant information on number and person. While object pro-drops are attested for some varieties of English, they are still relatively rare: According to the eWAVE, the feature (no. 42) is only found in 22 out of the 72 varieties for which information is available on the topic (Kortmann, Lunkenheimer & Ehret, Reference Kortmann, Lunkenheimer and Ehret2020). However, the availability of null-object marking is another feature present in Portuguese and is something that distinguishes it from other Romance languages, which require an overt referent (Cyrino & Matos, Reference Cyrino, Matos, Wetzels, Costa and Menuzzi2016: 296). Apart from the standard clitic pronouns -o(s)/-a(s) it appears to be the most frequent way to mark the third-person direct object in colloquial Madeiran Portuguese. According to Aline Bazenga (Reference Bazenga2019: 745), who conducted a corpus study of spoken Portuguese in Funchal, 36.4% of the data consisted of null-object marking (‘Faço o jantar e sirvo ∅ à familia. I cook dinner and serve ∅ to the family.’), followed by the use of the third-person singular masculine pronoun ele (19.6%) and the clitic -lhe (4.2%). We find an example of null-object marking in (4).

(4) ‘[ . . . ] if you are a lover or just curious to play golf you can also enjoy ∅.’ (PS-AC:005)

(b) Construction transfer/calques

In the corpus we can also find several examples of construction transfers or calques, which are more or less literally translated renderings of word forms or expressions from a source into a recipient language (Onysko, Reference Onysko, Zenner, Backus and Winter–Froemel2019: 42), or from L1 into L2. In example (5), the use of stays is likely a direct translation from the Portuguese ficar, which can be glossed as both ‘to be’ (in the sense of ‘to be located’) and ‘to stay’ (‘o condomínio fica na parte mais ensolarada da cidade’).

(5) ‘The condominium stays in the sunniest part of the city [ . . . ].’ (M-AC:072)

Example (6) demonstrates transfer of Portuguese number agreement (‘lives’) alongside the standard number marking used in English (‘are’), as a gente (lit. ‘the people’) is a singular noun in Portuguese.Footnote 9

(6) ‘The people who lives in the neighbours are simple, modest and friendly’ (M-AC:083)

Examples of literally rendered lexical units can be found in (7) and (8): ‘to take (any) doubts’ is likely a direct translation of tirar (quaisquer) dúvidas, meaning ‘to clear/resolve/take away any doubts’, whereas ‘taking the sun’ is a translated rendering of tomar sol ‘to sunbathe’.

(7) ‘We will be always available to take any doubts before or during the stay.’ (PS-AC:006)

(8) ‘Go up to the terrace and enjoy the view of the waterfalls and banana plantations, relax while taking the sun or reading a book’ (M-AC:125)

Another interesting case can be found in (9), where the writer uses a head-initial compound which is a direct translation of the Portuguese expression energia eléctrica ‘electric power’:

(9) ‘Thanks you for helping save water and energy electric.’ (M-AC:110)

Further examples include calques of words which are polysemic in Portuguese, such as coffees for ‘cafés’ (PS-AC:003) from Portuguese café (which can mean ‘coffee’ but also ‘café’); cook bread (M-AC:093) from Portuguese cozer (‘to cook/bake’).

(c) Agreement and number

Examples such as (10) and (11) occur frequently in the corpus. A likely explanation for a lack of agreement is that, as has been found for other varieties of English and in ELF contexts, agreement is often not required for successful communication (see, for instance, Ji, Reference Ji2016). It is also possible that some authors did not proofread their ads or pay particular attention to producing standard-like English and therefore opted for variants that are easiest to produce in the moment of writing. However, the authors potentially rely on the income generated by their Airbnb rentals. Thus, the more likely option might be that language users did, in fact, proofread the ads but the constructions did not strike them as problematic.

(10) ‘This beautiful house in Prazeres will surely make your holidays a very happy one! The stone exterior and cosy interior lends an unforgettable charm to this home, and is an oasis of peace.’ (M-AC:039)

(11) ‘It is also near the stops of every bus lines that go everywhere around the island.’ (M-AC:073)

Other examples, such as (12), might be instances of hypercorrection. In these cases, the authors might have added the third-person singular ending in order to be ‘more correct’. Alternatively, the lack of agreement might be in the noun, with each leading the author to use a plural noun.

(12) ‘Each cottages offers WiFi, streaming services and cable TV.’ (M-AC:027)

(d) Count/non-count

The pluralization of non-count nouns is a typical feature found in many varieties of English (see feature 55 in the eWAVE, Kortmann et al., Reference Kortmann, Lunkenheimer and Ehret2020). Schneider, Hundt and Schreier (Reference Schneider, Hundt and Schreier2020: 541) note that English as a Second Language (ESL) varieties have ‘a higher tendency for non-count noun pluralization’ compared to English as a Native Language (ENL) varieties, although differences are often not that clear-cut. We found several instances of non-count noun pluralization (13–14) as well as non-count nouns with articles (15) in the Airbnb corpus. Apart from the general tendency of ESL varieties to disregard the count/non-count distinction, there is also some evidence that it might be a transfer feature in our data. Portuguese equipamento (Eng. equipment), herança (Eng. heritage), and transporte público (Eng. public transport) are all countable, which could explain their usage as count nouns in the examples.

(13) ‘All our guests have free access to the swimming pool, solarium, grill and its equipments’ (M-AC:027)

(14) ‘There are public transports to this location’ (M-AC:023)

(15) ‘Very welcome to our family holidays house, an heritage from our grandfather’ (PS-AC:001)

(e) /h/ deletion

European Portuguese does not have a phoneme /h/ and this seems to be transferred into the speakers’ pronunciation of English words and, via this, into writing. In some examples, as in (16) and (17), writers leave out the letter <h> altogether:

(16) ‘Our village as beautiful places to visit [ . . . ]’ (M-AC:057)

(17) ‘It as a big terrace [ . . . ]’ (M-AC:097)

In other examples, such as (18) and (19), the use of the indefinite article an instead of a suggests /h/ deletion in the subsequent word:

(18) ‘the rest of an hammock’ (M-AC:065)

(19) ‘Very welcome to our family holidays house, an heritage from our grandfather’ (PS-AC:001)

(f) Lexical transfer

Furthermore, transfer from Portuguese could also be found on the level of lexis. Lexical transfer seems to be strongly due to cognates, i.e., words which have a common etymological ancestor. In some cases, this mostly affects word spelling (and, possibly, pronunciation), in others, semantic concepts are transferred as well. The Airbnb corpus analysed for this study contains examples of:

• Direct transfers from Portuguese, e.g., writers use words such as tradicional ‘traditional’ (e.g., M-AC:03); M-AC:083), táxis ‘taxis’, gás ‘gas’ (M-AC:079), metros ‘metres’ (M-AC:082), minutos ‘minutes’ (M-AC:104), sofá ‘sofa’ and pizzarias ‘pizzerias’ (M-AC:104), varanda ‘veranda’ (M-AC:107), máx. two people ‘max. two people’ (M-AC:129), adicional ‘additional’ (M-AC:136), restaurantes ‘restaurants’ (M-AC:136), residencial ‘residential’ (PS-AC:025), área ‘area’ (M-EX:005), etc. Given the nature of the data analysed, these examples could theoretically also be due to the autocorrect function of the writers’ computers. However, as most hosts are likely to proofread their ads before posting them on the website (see above), we can at least assume that these transfers were not detected during this process, i.e., they seem to be inconspicuous for the respective writers.

• Spelling variants which exhibit influence from the writers’ L1, e.g., confort/confortable (e.g., M-AC:03) for ‘comfort’ (adapted from Portuguese conforto/confortável), duche ‘shower’ (M-AC:032) from Portuguese ducha, vulcanic (M-AC:063) for ‘volcanic’ (adapted from vulcânica/o).

• Transfer from Portuguese which results in an existing English word but leads to semantic change: cultural patrimony from Portuguese património ‘inheritance’ (M-AC:033), a very distressed view for ‘a view to de-stress’ (M-AC:072) (from destressar), the confection of the meal for ‘the preparation of the meal’ (M-AC:126) (from confeccionar ‘to make’), cabins for ‘changing cubicles’ (M-EX:012) from Portuguese cabine de banho.

• Borrowings from Portuguese which are not due to cognates. These are typically used to refer to cultural concepts or toponyms, e.g., miradouro ‘viewing point’ (M-AC:009), veredas ‘paths’ and levadas ‘irrigation channels’ (e.g., M-AC:010), or quinta ‘country house’ (M-AC:024). Some of them are specific to the Madeiran context, e.g., levadas, lambecas (PS-AC:021) (referring to ice cream from a specific ice cream parlour on Porto Santo), and poncha (M-EX:005) (a traditional drink). Other borrowings are related to flora and fauna, e.g., urzes ‘heather’ (M-AC:010). Sometimes writers highlight the Portuguese loanwords through the use of quotation marks, but they can also be incorporated into the text without extra marking.

• Transfer from Portuguese which does not lead to an existing English word but shows phonological adaptation, e.g., you can deslocate more easily (M-AC:016), where Portuguese deslocar ‘to move’ is transferred into English, mirroring dislocate; or planted in the old and recouped terraces (M-AC:079) where the writer uses the Portuguese lexeme recuperar ‘to restore’ and submits it to English inflection rules.

(g) Hybrid compounds

Hybrid compounds, consisting of an English and a Portuguese or Romance component, constitute a special and creative variant of lexical transfer and have been noted as a common feature in World Englishes (cf. Biermeier, Reference Biermeier2008). In many cases, they involve toponymic expressions, as in (20), where the writer uses the Latin laurisilva (‘laurel forest’) as a modifier for the English forest, thus mirroring the Portuguese compound floresta laurissilva ‘laurel forest’ (also note the spelling here). However, while in Portuguese, the heads of subordinate compounds would typically be on the left (Villalva & Gonçalves, Reference Villalva, Gonçalves, Wetzels, Costa and Menuzzi2016: 182), the construction in (20) follows the English order in that it first provides a modifier (Laurissilva) and then the head (forest).

(20) ‘To the north you will find impetuous mountains of Madeira island with all the beauty of Laurissilva forest’ (M-AC:023)

Other hybrid compounds follow the English modifier-head rule. In these cases, the Portuguese element always takes the role of the modifier, specifying the English head component, as in (21) and (22).

(21) ‘Levada walks and miradouro with beautiful sunset.’ (M-AC:009)

(22) ‘beautiful traditional ‘casa de campo’ houses’ (M-AC:120)

(h) American English vs. British English spelling

Spelling in the Airbnb corpus varies between American and British English, but there is a tendency towards American spellings. We could find examples of both variants for many words, but the American spelling variant was more frequent for all words we considered. Four examples including their absolute frequencies are given in Table 1. The indicated frequencies include all derived lexemes, compounds, and word-forms (e.g., center includes centers; neighbour includes neighbourhood, etc.).

Table 1: American and British English spelling variants in the Airbnb corpus

A study by Gonçalves et al. (Reference Gonçalves, Loureiro-Porto, Ramasco and Sanchez2018) shows that Portuguese speakers of English generally favour American variants in both spelling and vocabulary. In addition, it is likely that there is a ‘push and pull’ between American and British variants in Madeira due to the island's historical ties to England on the one hand and exposure to American English and the ‘Americanization’ of English, proposed by Gonçalves et al. (Reference Gonçalves, Loureiro-Porto, Ramasco and Sanchez2018), on the other hand.

Interpreting variation in the corpus

Explaining why authors of the ads selected these variants over others requires considering numerous factors, as mentioned above. Language contact is likely to play a role, which means that elements or structures from the writers’ L1, Portuguese, might have been transferred to English. It is important to stress that the Portuguese spoken in Madeira is characterised by dialectal variation (Cintra, Reference Cintra and Franco2008: 99). This means that change potentially caused or influenced by language contact requires in-depth comparisons, which is beyond the scope of this article. However, we have found potential evidence for language contact in our Airbnb corpus: Besides a large amount of lexical transfer, which is characteristic for early stages of language contact (Thomason, Reference Thomason2001: 70–71), the existence of hybrid compounds already suggests more intense contact processes (cf. Schneider, Reference Schneider2007: 46). Apart from that, Portuguese influence could also be detected on other linguistic levels. However, as the role of English in Madeira is a complex one, these findings are not easy to interpret. English is a compulsory subject for Portuguese schoolchildren, but it is typically acquired in secondary and particularly in vocational education and not as a first language (European Commission, 2017: 82).

At the same time, the role English plays in Madeiran everyday life must not be underestimated: More Madeirans are employed in tourism (16.7%) than in any other sector (see DREM, 2018, 2021a). That is, they work in an area where at least some knowledge of English is required. One of the side effects of increased globalisation, (mass) tourism, has been described as belonging to the set of extra- and intra-territorial forces (Buschfeld & Kautzsch, Reference Buschfeld and Kautzsch2017: 113–115) influencing the development of English varieties. English is thus not only acquired in the school context but also in direct interaction with tourists (who might be native speakers of English but could also merely resort to English as a Lingua Franca). The emerging ‘grassroots Englishes’ are marked by a very clear functional orientation, as they are targeted at ‘highly specific contexts, associated with narrowly circumscribed proficiency requirements’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider2016: 5). In this respect, the situation on Madeira can be compared to that of other tourism destinations which experience a spread of English due to increasing interactions between locals and tourists. However, what sets Madeira apart from, e.g., the Maldives (Meierkord, Reference Meierkord2018), is that its history of tourism goes back to the 15th century and English-speaking visitors have always made up a major group. Madeira thus constitutes an interesting case for investigating the interaction between different types of learner Englishes and their potential way towards an emerging variety of ‘Madeiran(ized) English’.

Conclusion and outlook

With some exceptions (e.g., Friedrich & Berns, Reference Friedrich and Berns2003), the role of English in countries with a dominant Romance language, in particular European Portuguese, has not been scrutinised. However, the example of Madeira is not only a remarkably interesting case of ELF usage but, since the island had quasi-colonial ties to the British Empire, also represents a fascinating case of a lesser-known variety (Schreier, Reference Schreier2009) with English primarily functioning as a second language. The history of English in Madeira can be described as one of trade colonialism, which led to the importance of English as the language of Madeiran tourism today.

Our mostly qualitative overview of some linguistic features of English in Madeira has shown that the variety shares a lot with other World Englishes, but also has unique features. These are indicators that English in Madeira is an invaluable research subject not only for its idiosyncratic history but also its linguistic diversity.

This brief overview article is the first publication on a fascinating variety that deserves further recognition in World Englishes scholarship. It also marks the inception of a larger collaborative project on English in Madeira: Future research will analyse the variety in the context of different World Englishes models (such as Schneider's [2007] Dynamic Model, and Buschfeld and Kautzsch's [2017] Extra- and Intraterritorial Forces Model), describe the variety and its features on all linguistic levels in more detail (based on diverse datasets), and investigate attitudes towards English in Madeira.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. All remaining errors are entirely our own.

SVEN LEUCKERT is a postdoctoral researcher and research associate at Technische Universität Dresden, Germany. He received his PhD in English Linguistics in 2017 with a thesis on topicalization in Asian Englishes. His main research interests are World Englishes, non-canonical syntax, the sociolinguistics of CMC, and corpus linguistics. Email: [email protected]

SVEN LEUCKERT is a postdoctoral researcher and research associate at Technische Universität Dresden, Germany. He received his PhD in English Linguistics in 2017 with a thesis on topicalization in Asian Englishes. His main research interests are World Englishes, non-canonical syntax, the sociolinguistics of CMC, and corpus linguistics. Email: [email protected]

THERESA NEUMAIER completed her PhD on turn-taking in varieties of English in 2019 at the University of Regensburg and is currently working as a postdoctoral research associate at TU Dortmund University, Germany. Her research focuses on World Englishes, Conversation Analysis, and the relation between language and culture. Further research interests include non-canonical syntax, discourse analysis, and historical pragmatics. Email: [email protected]

THERESA NEUMAIER completed her PhD on turn-taking in varieties of English in 2019 at the University of Regensburg and is currently working as a postdoctoral research associate at TU Dortmund University, Germany. Her research focuses on World Englishes, Conversation Analysis, and the relation between language and culture. Further research interests include non-canonical syntax, discourse analysis, and historical pragmatics. Email: [email protected]

ASYA YURCHENKO is currently a research assistant and master's student of English linguistics at the Technische Universität Dresden. Her research interests include corpus linguistics, World Englishes, stylistics and stylometry, and multimodality in communication. Email: [email protected]

ASYA YURCHENKO is currently a research assistant and master's student of English linguistics at the Technische Universität Dresden. Her research interests include corpus linguistics, World Englishes, stylistics and stylometry, and multimodality in communication. Email: [email protected]