1. Introduction

The linguistic landscape of any country reveals a lot about the linguistic identity of its citizens, especially if it is a bottom-up linguistic landscape. In Algeria, which is a multi-cultural and multi-lingual context, the linguistic landscape witnessed a remarkable shift in linguistic preferences that is represented in bottom-up signs. This shift is characterized by the addition of a new linguistic entity, English, to the Algerian linguistic landscape. In Algerian society, it is easily observed that English is not commonly present in the top-down signs assigned by the Algerian government, which contrasts with the signs of private businesses such as fashion shops, restaurants, and coffee shops. In fact, English has been found in Algerian signs since the 1990s when foreign energy companies like British Petroleum (BP) arrived and introduced the language in the country (Euromonitor, Reference Euromonitor2012), but it has become prevalent in the bottom-up signs of private businesses, which were previously dominated by other languages, i.e., Arabic and French. For those who are unfamiliar with the Algerian context, Arabic and Berber (or Tamazight) are the official languages of the country while French and English are the foreign languages. French is the first foreign language, while English is the second foreign language. Despite this clear linguistic planning, there has been unclear planning of the linguistic landscape on the part of the Algerian government, mostly in top-down signs. For instance, the government uses monolingual and bilingual signs that disregard English in the majority of signs. The monolingual signs are either Arabic or French. Berber is used in monolingual signs only in cities of Berber ethnicity. On the other hand, the bilingual signs are mostly written in Arabic and French or Arabic and Berber, the latter signs being found only in Berber-ethnicity cities such as Bejaia, Khenchela, Batna, and Tizi Ouzou. Overall, the government and Algerian citizens have rather different linguistic landscape practices since Algerians opt for integrating English, the language of globalization, presenting it in different bottom-up signs alongside other languages.

Several studies have recently discussed the bottom-up linguistic landscape in Algeria by focusing on the interpretations of the different languages used. For instance, Belaidi (Reference Belaidi2020) studied the use of three languages – Arabic, Tamazight and French – in bottom-up signs, exploring the connotations of each language. Belaidi (Reference Belaidi2020) shows that Arabic represents the official and Islamic language, Tamazight represents a rejected language that became official after protests, while French symbolizes the prestige of the sign owners and the business itself. Belaidi (Reference Belaidi2020) suggested that the way these languages were interpreted led Algerian society to develop feelings of discrimination as a result of those language choices. While Belaidi's (Reference Belaidi2020) study did not include English in the scope of his research, Nakla (Reference Nakla2021) focused on the use of four languages, including English, in a local Algerian context (a public neighborhood in the city of Oran). In Nakla's study, English was described as the global language, which was attributed as an explanation for its usage. Another study by Sidhoum (Reference Sidhoum2016) highlighted that English is mostly used in fashion and food signs in a local city in Algeria (Bouira city). In this study, the English language is described as a Trojan horse (Sidhoum, Reference Sidhoum2016: 3) because it is spreading in Algeria due to globalization.

Taking the research context into consideration, to the best knowledge of the researcher, no previous studies appear to have provided a timeline explaining the development of perceptions towards the use of English in bottom-up signs, and previous studies did not mention reasons beyond the obvious one of globalization for the use of English. Having considered the findings of these studies, the current study aims at highlighting the spread of English in bottom-up signs in three local contexts in Algeria, i.e. Algiers, Biskra and Constantine. The study establishes a timeline for the booming wave of English in bottom-up signs, explicitly clarifying the reasons behind this wave, and pinpointing some new representations and connotations of English from the perspective of different business owners.

2. Theoretical framework

Linguistic landscape analysis is a commonly used methodology (e.g., Rosenbaum et al., Reference Rosenbaum, Nadel, Cooper, Fishman, Fishman, Cooper and Conrad1977; Blommaert & Maly, Reference Blommaert and Maly2014; Edmond, Reference Edmond2017) in studies attempting to define or represent the identity of a country; it seeks to answer the questions ‘what’, ‘how’ and ‘why’ to gain a comprehensive understanding of the linguistic landscape domain. The ‘what’ questions respond to the types of signs, the materials involved in their creation, and the languages written on them. The ‘how’ questions refer to the way society and ethnography affect the establishment of signs, and the ‘why’ questions delve into the far-reaching reasons that explain the language choices on signs. Landry and Bourhis (Reference Landry and Bourhis1997) define linguistic landscape as ‘[t]he language of public road signs, advertising billboards, street names, place names, commercial shop signs, and public signs on government buildings combined to form the linguistic landscape of a given territory, region, or urban agglomeration’ (p. 25). In their definition, Landry and Bourhis (Reference Landry and Bourhis1997) attribute the linguistic landscape to all visually written signs that can be found in open spaces. Another definition by Mensel, Vandenbroucke and Blackwood (Reference Mensel, Vandenbroucke, Blackwood, Garcia, Flores and Spotti2016) focuses on highlighting the area and scope of linguistic landscape research. They summarize that ‘[t]he study of the linguistic landscape (LL) focuses on the representations of language(s) in public space. Its object of research can be any visible display of written language (a “sign”) as well as people's interactions with these signs’ (p. 423).

In the linguistic landscape literature, two main types of linguistic landscape are subject to careful investigation in all prominent studies of the field. These types are top-down and bottom-up, and both serve different functions. Top-down signs present the civic authorities’ power (Kallen, Reference Kallen, Jaworski and Thurlow2010), impact bottom-up signs (Gorter & Cenoz, Reference Gorter, Cenoz and Hornberger2007), and reflect ‘a general commitment to the dominant culture’ (Ben–Rafael et al., Reference Ben–Rafael, Shohamy, Amara and Trumper–Hecht2006: 10). On the other hand, bottom-up signs are non-governmental signs that express personal choices (Backhaus, Reference Backhaus2006). The present research focuses on bottom-up signs, which are defined as ‘private signs such as the signs on shops and they may be influenced by language policy but mainly reflect individual preferences: shops, advertising, private offices’ (Gorter & Cenoz, Reference Gorter, Cenoz and Hornberger2007: 6). Put differently, bottom-up signs are non-official signs with language choices selected based on personal preferences. However, the personal choices are not arbitrary, but are based on ‘covert solidarity’ (Backhaus, Reference Backhaus2006) between members of a speech community and through strategies based on common benefit (Ben–Rafael et al., Reference Ben–Rafael, Shohamy, Amara and Trumper–Hecht2006) such as economic considerations and individual preferences. The freedom of sign selection does not make this type of sign free of problems since they have to cope with ‘ . . . internationally recognized image (global signs) . . . local policies, and . . . own linguistic competencies and those of intended readers’ (Pavlenko, Reference Pavlenko2009: 250). Thus, bottom-up signs are governed by international, national, and linguistic conventions despite their apparent freedom.

The current study starts from the view that the Algerian bottom-up linguistic landscape results from the social role played by English in the society and its associated symbolism. Therefore, we adopt the view of the linguistic landscape put forward by Mensel et al. (Reference Mensel, Vandenbroucke, Blackwood, Garcia, Flores and Spotti2016), which is that it is ‘ . . . a reflection of the role played by language in society/ societies, sometimes directly, sometimes indirectly, and at times distortedly . . . ’ (p. 424); and that there is a need to investigate the synchronic and diachronic interpretations of social developments that influenced the making of current signs. Hence, the timeline presented in the current study will help to understand the social developments in Algerian society which allowed English to be present in bottom-up signs.

As stated above, the current study aims to reveal the incidence and connotations of the English language in bottom-up signs. Therefore, reference is made to the symbolic function of the linguistic landscape. In order to illustrate this phenomenon, symbolism is linked to the value and status of a language among other languages in one sign.

3. Methodological considerations

The current study focuses on the social aspect of the linguistic landscape discussed by Mensel et al. (Reference Mensel, Vandenbroucke, Blackwood, Garcia, Flores and Spotti2016), who clarify that the linguistic landscape is a reflection of the role played by language in the society. As such, linguistic data on bottom-up signs was collected and their connotations and representations in Algerian society were interpreted. The point at which English signs started to widely spread in Algeria and big Algerian cities was identified based on both the observations of the first author and also writings about it. A timeline of the spread of English was then compiled by referring to the earliest social media posts of the businesses under study and to field observations. Later, business owners were interviewed and pictures of different businesses were collected to explain the choices of English signs and the representations associated with English.

The observations for the purpose of this research officially started in 2018. However, the first author (as an Algerian) has been observing the change in the linguistic landscape since 2009. Therefore, the timeline relies on both official and non-official observations conducted by the first author. Semi-structured interviews with three owners of different businesses, i.e. fashion shops, perfume shops, and restaurants were conducted in 2019, while photographs were collected since 2018. The interviewees were aged between 28 and 29 years old and were from different cities (Algiers, Constantine and Biskra) and they have been assigned pseudonyms to maintain their anonymity.

4. English in bottom-up signs in Algeria

Recently, English has become a common feature of bottom-up signs in Algeria. These signs are found not only in the cities that the study covers, but also in many other small towns and large cities. The first example of these signs is Downtown restaurant, which is located in the center of Algiers.

Figure 1 shows the front sign of the Downtown restaurant, which is written in English and ‘Arabized’ English. In other words, the word downtown is written in Arabic letters by keeping the same English pronunciation. The front of the restaurant also includes the use of written English words to present the main menu of the restaurant (pizzas, pastas, burgers, salads, tacos, and pinchos), obviously influenced by American and international cuisines.

Figure 1. Bilingual sign of Downtown restaurant

Another influence on the Algerian linguistic landscape appears to be the English football culture.

The restaurant in Figure 2 is part of a theme-based restaurant chain located in Kalitous (Algiers). The first part of the chain is themed as Chelsea, referring to Chelsea Football Club and it serves Shawarma (famous Middle Eastern food). The second part of the chain is named after Arsenal Football Club and serves pizzas, while the third part of the chain is named after Liverpool Football Club and serves tacos and burgers. It must be highlighted that this chain is very popular among Algerians, especially those who support these three football clubs.

Figure 2. English football culture in bottom-up signs

Figure 3. Fashion shop signs in English

Besides the restaurants, there are fashion shops that use English on their signs, such as Eyewear and Sugar in Algiers.

These shops are among many other shops that choose to use English on their signs. It must be noted that these shops are known for their good quality and prestige in the city of Algiers.

In the educational field, private English-language schools rely on using English on their signs. Figure 4 is an example of these signs.

Figure 4. English on private school signs

Another observation of such schools’ signs is their use of American and English flags along with the English language. It has become very common to see American and English flags in Algerian streets as part of the design of these signs.

5. Timeline of the wave of bottom-up signs

Knowledge of when the English language started to spread in the Algerian linguistic landscape enables understanding of social development and change over the years, and permits exploration of the reasons behind its use and prediction of its future in Algeria. Unfortunately, as stated above, no studies have deliberately accounted for the chronological development of English bottom-up linguistic landscape signs in Algeria. In the absence of such a source, presumptions of this development are highlighted next from the perspective of the interviewed shop/restaurant owners and other observed businesses launched in recent years.

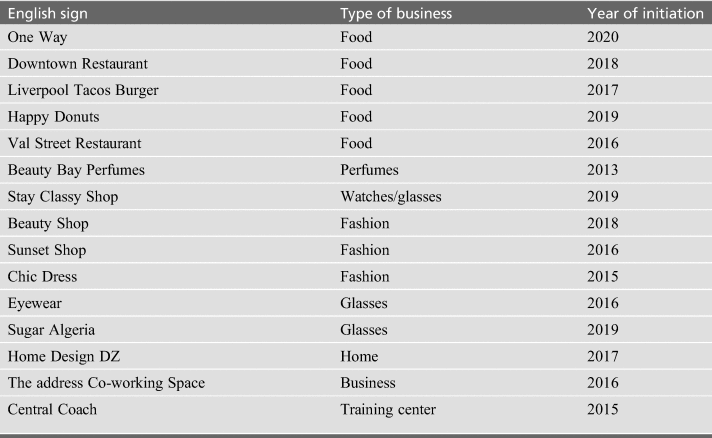

Table 1 represents 15 private businesses which were closely observed to have a major impact in Algeria in terms of their good quality, reputation, and fame. These 15 businesses are not the only source of the timeline conclusions, but are among other numerous small businesses in the linguistic landscape of the three cities under research (Algiers, Constantine and Biskra).

Table 1: Private businesses and when they were founded

The businesses in Table 1 focus on a variety of areas. In other words, English-language signs are not exclusive to fashion and food businesses. However, they became very common in different fashion sectors (glasses, perfumes, watches and clothes), home fashion, language schools, and business and training centers. This variety of businesses made English-language signs more noticeable in the Algerian linguistic landscape.

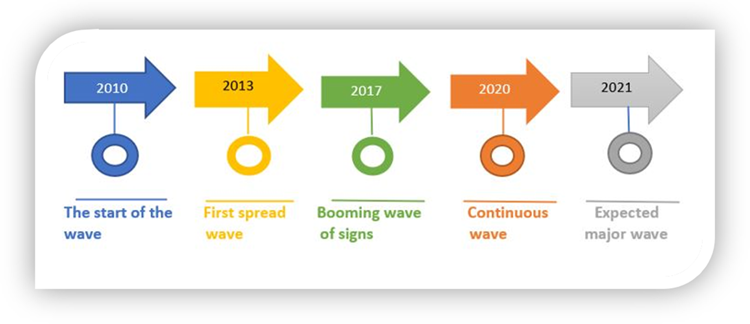

Based on our observation, memories, the previous table, the social media official accounts of these businesses and their earliest publications, and the interviews conducted with three owners of businesses mentioned in Table 1, the following account can be presented. Algeria has undergone a booming wave of English-language signs starting in 2010 with larger spread in 2013 to boom in 2017, and to continue to 2020 and it is expected to result in a major wave in 2021. In 2010, the wave was not as significant as in 2013 since there were few English signs in 2010. However, by 2013, more businesses followed the wave. In 2017, on the other hand, bottom-up signs were easily and clearly observed in the Algerian linguistic landscape, which is why it is described as the year of the booming wave. In the following years, English appeared to become a trend among new business owners who continued to use English in their signs. Therefore, the timeline is expected to progress according to the trending wave that occurred in previous years. Figure 5 interprets these findings in a timeline that illustrates the start of the wave of bottom-up linguistic landscape signs in Algeria.

Figure 5. Timeline of English bottom-up signs in Algeria

Figure 5 does not deny the fact that that there were English signs in Algeria before 2010. However, it indicates the real starting wave for the massive use of these signs which can be easily observed in the Algerian linguistic landscape.

6. Incidence and connotations of English signs

The timeline in Figure 5 demonstrates that there was a booming wave of English signs in private businesses of different types in Algeria, which is due to a sociolinguistic change that became visible in the linguistic landscape. In this section we discuss the reasons behind the sociolinguistic development and change, as well as the current connotations and representation of English in Algerian society.

Regardless of the fact that globalization is the main reason for the presence of English in Algeria, other reasons such as traveling and tourism helped to initiate the change in the Algerian linguistic landscape. One perfume shop owner explains:

I like traveling and I use English in my travels to communicate with people (Salah, 35, Biskra)

In addition to traveling and tourism, the return of Algerian diaspora to do business in Algeria permitted experience and linguistic sharing. One of the business owners (glasses and watches shop) clarifies that:

I lived in Germany, I also lived in Kuwait and Cyprus. When I came to Algeria, it was logical that I use what I saw in those countries in my country; for example, the brands I sell, the design of my shop and the English you see in the outside sign. (Nassim, 29, Constantine)

The English language is used not only in shop or restaurant signs, but also in the interior decoration, official logos, and slogans of the shops.

The interior of a restaurant in Figure 6 shows the use of different shapes with random English expressions, such as ‘it has become wildly impossible to be in love with you’, ‘welcome’, and ‘pizza, the best on the road’.

Figure 6. English in the interior décor

Figure 7 shows the slogan of a restaurant, ‘food with passion’, which represents the philosophy of the restaurant and the way food is prepared in this place.

Figure 7. English in the logo and slogan of a restaurant

Another reason for using English in signs is the fact that they imbue these businesses with prestige, modernity, and attraction.

The number one reason is I prefer English over French. Also, it's like a conversation starter between me and my clients in the first days of having my shop and it kind of adds prestige to the shop. (Salah, 35, Biskra)

I named it in English in order to look modern, to look attractive, to be something different from the other shops. (Nassim, 29, Constantine)

As you can see, I used English in the sign and in the decoration; I think this is catchy because people would feel they are in America or England, which makes it look very modern to them and make them come here more. (Hicham, 28, Algiers)

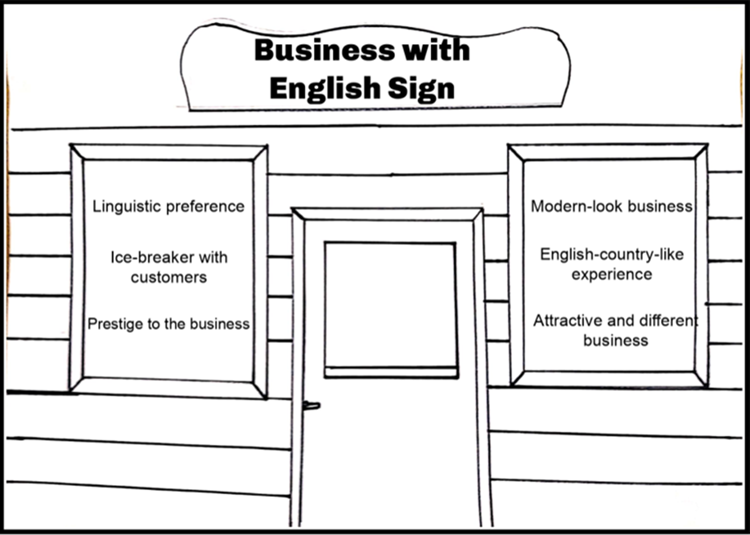

The following sketch (Figure 8) summarizes the main reasons for the shop and restaurant owners to use English in their signs. The reasons include ideas such as linguistic preference, ice-breaker with customers, adding prestige to the business, modern-looking business, English-country-like experience, and being an attractive and different business. The sketch was drawn by a professional in interior design to illustrate an imaginary business front (for the purposes of the current study), while the content is the summary of the authors.

Figure 8. Connotations of English in bottom-up shop signs

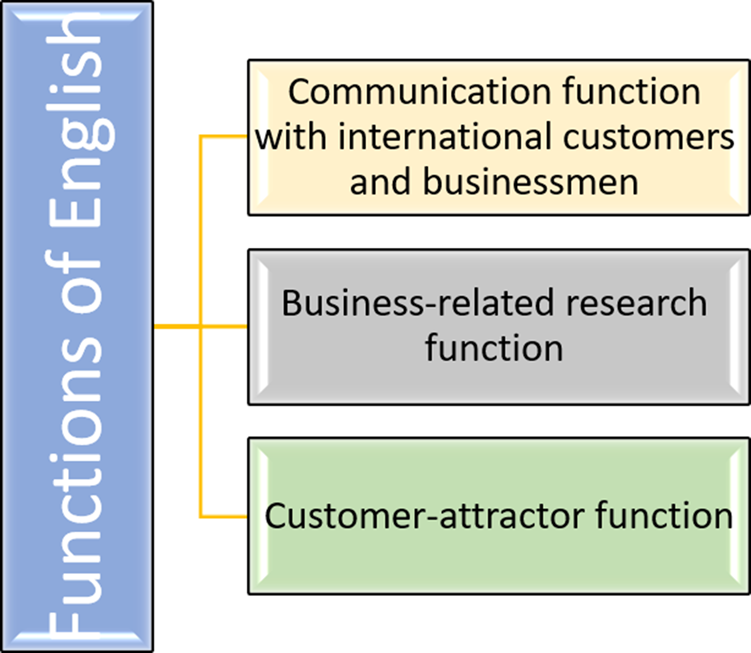

The connotations of English-language signs show that beliefs developed in Algerian society that the English language is associated with prestige and modernity. The interviewees also explained that English serves other functions, which are summarized in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Functions of English for business owners

Figure 9 summarizes the functions discussed by the interviewed shop and restaurant owners. These functions are:

i. Communicative functions with international customers and businesspeople; i.e., English helps business owners to communicate with international customers and businesspeople;

ii. Customer-attractor function; i.e., businesses with English signs attract more customers because they look more prestigious and modern; and

iii. Business-related-research function; i.e., English allows business owners to find products easily on the internet since most online information is presented in English.

These functions are specific to shop and restaurant businesses. Other functions may occur according to the nature of the business.

7. Conclusion

The current study has discussed sociolinguistic development and change in Algerian society that resulted in a booming wave of English bottom-up signs. The sociolinguistic development was highlighted through a progress timeline that clarified that the booming wave started in 2017 and that its development continues. Bottom-up signs in the Algerian linguistic landscape are found not only in fashion and food businesses, as mentioned by Sidhoum (Reference Sidhoum2016), but also in private language schools, training centers, business centers, and home-fashion stores. The variety of signs indicates the large-scale presence of English-language signs in the linguistic landscape.

Although the current study focused on three Algerian cities – Algiers, Constantine and Biskra – it does not refute the emergence of English signs in other Algerian cities that were observed for non-research purposes such as during personal travels. The presented timeline considered both official and non-official observations in the conclusions drawn, and confirmed the spread of English signs with underlying sociolinguistic factors. The study confirms that the main factor is globalization, as discussed by Nakla (Reference Nakla2021), but reveals other reasons related to the connotations and representations of the English language. The most common connotation relates to the newly associated belief of English as the language of prestige and modernity. In other words, businesses with English signs are believed to be prestigious and modern and, eventually, as having good product quality. The study also clarifies that those English signs are a result of a linguistic preference of the business owners who are mostly frequent travellers or returned diaspora. In general, English signs are an adequate interpretation of the beliefs, attitudes, and practices of the society, which developed new linguistic preferences and language-related beliefs (of prestige and modernity) to explain the sociolinguistic development and change in Algeria. The linguistic landscape is a pure reflection of the role played by language in society (Mensel et al., Reference Mensel, Vandenbroucke, Blackwood, Garcia, Flores and Spotti2016).

The linguistic landscape provides an index for the status and power of language in the speech community (Landry & Bourhis, Reference Landry and Bourhis1997). In the same vein, the current study reveals that connotations of the English language, along with the functions it serves for business owners, determine the status and power of the English language in Algerian society. In other words, English is not only the language of prestige, modernity or attraction. English also serves many functions for business owners. These functions are effective in both local and international settings since they ease communication with international customers and businesspeople and help business owners to find better-quality products. With the intertwined connotations and functions of English in bottom-up signs in Algeria and the functions it serves in connecting Algerian businesspeople with their international counterparts and customers, the change in the linguistic landscape towards English is expected to continue. This is a sociolinguistic reflection of Algerian society. Therefore, further research is highly recommended to track the expected changes in the Algerian linguistic landscape.

BAYA MARAF is a PhD researcher at Eastern Mediterranean University, North Cyprus. Her research interests cover areas of language policy and planning, pragmatics and sociolinguistics. Email: [email protected]

BAYA MARAF is a PhD researcher at Eastern Mediterranean University, North Cyprus. Her research interests cover areas of language policy and planning, pragmatics and sociolinguistics. Email: [email protected]

ULKER VANCI OSAM is a professor at the English Language Teaching Program of the Faculty of Education, Eastern Mediterranean University, North Cyprus. Her research and teaching interests include language teacher education, teacher identity, professional development, and English language teaching methodology. Email: [email protected]

ULKER VANCI OSAM is a professor at the English Language Teaching Program of the Faculty of Education, Eastern Mediterranean University, North Cyprus. Her research and teaching interests include language teacher education, teacher identity, professional development, and English language teaching methodology. Email: [email protected]