1 Introduction

Pseudo-partitives are strings of the form [N1 – of – N2], in which N1 denotes a quantity or amount of whatever it is that N2 denotes. Keizer (Reference Keizer2007: 109) distinguishes between five types, adapting a classification proposed for Dutch in Vos (Reference Vos1999).

(1)

(a) Quantifier-noun constructions: a number of people

(b) Measure-noun constructions: a pint of beer

(c) Container-noun constructions: a box of chocolates

(d) Part-noun constructions: a piece of cake

(e) Collection-noun constructions: a herd of elephants

Characteristic of pseudo-partitives is that N2 is a bare nominal. It is in this respect that it differs from genuine partitives, in which N2 is introduced by a definite determiner. Compare the pseudo-partitive a piece of cake with the partitive a piece of the cake.

Orthogonal to the semantic classification in (1) is the distinction between pseudo-partitives that are headed by N1 (type A) and pseudo-partitives that are headed by N2 (type B). A classical test to differentiate them is based on agreement with the finite verb, as in (2)–(3).

(2)

(a) [A pound of cucumbers] yields about a pint of pickles.

(b) [Roughly five billion pounds of carpet] end up in landfills each year.

(3)

(a) [A lot of things] happen and change over the years.

(b) [Lots of power] is necessary to churn heavy soil.

In (2) the finite verb shares the number value of N1 (pound, pounds). This conforms to the expectation that N1 is the head in a [N1 – of – N2] combination. In a pound of cucumbers, for instance, it is the singular pound that heads the phrase and that determines the number value of the NP, in the same way as picture heads the phrase and determines the number value of a picture of playing children. By contrast, in (3) the finite verb shares the number value of N2 (things, power), which suggests that the head of these [N1 – of – N2] combinations is N2. Many proposals have been made to accommodate this unusual pattern, but none is convincing, since they all resort to ad hoc departures from general principles on constituency and feature propagation (section 2). A first objective of the article is therefore to provide an analysis of both types of pseudo-partitives that is maximally compatible with independently motivated principles (section 3). For that purpose we employ the framework of Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar. A second objective is to explore how the distinction between the two syntactic types relates to the semantic classification in (1) (section 4). For that purpose we make use of data from the 450-million-word Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA; Davies Reference Davies2008–). In a final part we extend the analysis to pseudo-partitives without of, as in a few hands and a dozen eggs (section 5).

2 Existing treatments

Pseudo-partitives of type A can be analyzed in the same way as most other [N1 – of – N2] combinations, i.e. as a right-branching structure, in which N1 is combined with a PP dependent, and in which the PP is headed by the preposition, as in figure 1. This straightforwardly accounts for the fact that the NP shares the number value of N1.

Figure 1. Type A pseudo-partitives

For pseudo-partitives of type B this structure is less appealing, though, since the noun that determines the number value of the combination (N2) is in a position from which it normally cannot do this. Various proposals have been made to solve this. Most treat N2 as the head and N1 as part of its specifier or modifier. An early proposal of this kind is Akmajian & Lehrer (Reference Akmajian and Lehrer1976). For the pseudo-partitive in (4), they provide the structure in figure 2.

(4) A number of stories about Watergate soon appeared.

The NP a number projects a QP to which of is transformationally adjoined. The preposition is explicitly claimed to ‘not form a constituent with the following Ń’(Akmajian & Lehrer Reference Akmajian and Lehrer1976: 402). Evidence for this claim is provided by the contrast between (5) and (6).

(5)

(a) A review [of a new book about French cooking] came out yesterday.

(b) A review came out yesterday [of a new book about French cooking].

(6)

(a) A number of stories about Watergate soon appeared.

(b) *A number soon appeared of stories about Watergate.

The fact that the [of – NP] sequence in (5) can be extraposed, while its counterpart in (6) cannot, is seen as evidence that the former is a constituent, more specifically a PP, while the latter is not. The same kind of structure is proposed in Selkirk (Reference Selkirk, Akmajian, Culicover and Wasow1977) and in Traugott (Reference Traugott, Eckardt, Jäger and Veenstra2008). The latter, taking a diachronic perspective, argues that type B is the result of a grammaticalization process that has type A as its origin. It is schematized in (7) (Traugott Reference Traugott, Eckardt, Jäger and Veenstra2008: 227).

(7) [NP1 [of NP2]] > [[NP1 of] NP2]

Head = NP1 > Head = NP2

NP1 + Mod > Mod + NP2

Figure 2. Type B pseudo-partitives (Akmajian & Lehrer Reference Akmajian and Lehrer1976: 398–9)

A variant of this treatment is that of Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff1977: 119–26). He treats of as a linking element, assigning a ternary structure, as in figure 3. A similar structure is proposed in Keizer (Reference Keizer2007: 149).

Figure 3. Type B pseudo-partitives (Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1977: 122).

An advantage of the analyses in figures 2 and 3 is that the sharing of the number value is in line with standard assumptions. There is a problem, though, with the treatment of of, as pointed out in Huddleston & Pullum et al. (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 351–2). To spell it out they use the sentences in (8)–(9).

(8)

(a) Most students like continuous assessment but [a lot __] prefer the old examination system.

(b) *Most students like continuous assessment but [a lot of __] prefer the old examination system.

(9)

(a) We called a meeting of the first-year students, [of whom a lot __] had complained about the assessment system.

(b) *We called a meeting of the first-year students, [whom a lot of __] had complained about the assessment system.

Example (8) shows that N2 can be omitted if its content can be retrieved from the context, if and only if the preposition is omitted as well, and (9) shows that N2 can be extracted only if the preposition is pied-piped. This suggests that of forms a syntactic unit with N2. To model this they adopt the same right-branching structure as for type A, albeit with the proviso that one has to imagine ‘the grammatical number percolating upwards from the oblique rather than being determined by the head’ (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 352). The resulting analysis is given in figure 4.

Figure 4. Type B pseudo-partitives (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 351)

This accounts for the data in (8)–(9), but it also has some problems of its own. First, it involves a violation of the otherwise valid assumption that a nominal shares the number value of its head. Second, it licenses the combination of the indefinite article with a nominal that is claimed to be plural, contrary to the fact that this combination is normally ill-formed (*a protesters). Third, the assignment of PP status to the combination of the preposition with N2 is at odds with the fact that it cannot be extraposed, as illustrated in (6).

Taking stock, there is no shortage of proposals on the structure of type B pseudo-partitives, but there is none that simultaneously accounts for the fact that N2 is the head and that of forms a syntactic unit – though not a PP – with N2. Section 3 will present a proposal that does.

Besides the issue of determining the structure of type B there is the question of which of the two structures is the relevant one for some given pseudo-partitive. In the introduction we have used the subject–verb agreement test for that purpose, but this test has its limitations, since not all pseudo-partitives are in subject position and since not all verbs show overt agreement. Moreover, there are agreement mismatches, as in (10) and (11), quoted from Pollard & Sag (Reference Pollard and Sag1994: 68–71).

(10)

(a) Eggs is my favorite breakfast.

(b) Eggs bothers me more than okra.

(11)

(a) The faculty are all agreed on this point.

(b) The faculty have voted themselves a new raise.

It is therefore common practice to use other criteria as well. We will discuss two of the more commonly adopted ones. The first is based on semantic selection. It is advocated in Akmajian & Lehrer (Reference Akmajian and Lehrer1976: 406–7), who argue that N1 is the head in (12a), since it is the bottle that broke, and that N2 is the head in (12b), since it is the wine that spilled.

(12)

(a) A bottle of wine broke.

(b) A bottle of wine spilled.

As pointed out by the authors, this criterion is sometimes at odds with the agreement test. In (13), for instance, the verb shows agreement with N1, but in terms of semantic selection the head is N2, since it is the wine that is fermenting.

(13) Two bottles of wine are/*is fermenting.

To solve the paradox, Akmajian & Lehrer (Reference Akmajian and Lehrer1976: 406–7) give precedence to the semantic selection test, adding that the agreement data should not be taken too seriously, since there are other cases of number mismatches, as in (10)–(11). A problem with that solution is that the noun that meets the semantic selection requirements of a verb can be arbitrarily deeply embedded in the NP, as in (14).

(14) He was drinking [a pint filled to the brim with a brownish mixture of beer and coke].

The liquid denoting nouns in this sentence are part of a PP[of ] that is part of a PP[with] that is part of a participial modifier of pint. Treating beer and coke as the head of the bracketed NP would yield a structure that is – to put it mildly – unfamiliar. Semantic selection is, hence, a shaky basis for motivating syntactic structure.

Another way out is suggested in Keizer (Reference Keizer2007), who claims that ‘it is possible for pseudo-partitives to have two heads: a semantic head (N2) and a syntactic head (N1)’ (Keizer Reference Keizer2007: 124). The two usually coincide, but in (13) they do not. A problem with this solution is the vagueness of the notion of semantic head. Let us, for instance, take (15), quoted from Keizer (Reference Keizer2007: 119).

(15) A glass of wine would make me incapable but not drunk.

The author treats N2 as the semantic head, since ‘it is obviously N2 which satisfies the selection restrictions of the verb’. It can be wondered, though, whether this is so obvious. Are the selection restrictions of the verb make such that they are fulfilled by wine and not by glass? Or, if the whole VP is taken into account, is it the wine that makes me incapable but not drunk, or is it the quantity of wine that makes me incapable but not drunk? For Keizer it is obviously the former, but the latter could be argued to be more plausible, for if a glass is replaced by twenty glasses or three bottles, the predicate no longer seems applicable. In sum, when decoupled from the notion of syntactic head, the notion of semantic head tends to become murky.

A third way to deal with (13) is to give precedence to the agreement test and to limit the relevance of semantic selection to instances where the agreement test is inconclusive. In that case, the pseudo-partitive in (13) is unambiguously of type A, having N1 as its head. This is the position that we adopt.

Another commonly used criterion is based on the lexical class of N1. For that purpose Keizer (Reference Keizer2007: 149) uses the classification in (1), repeated in (16).

(16)

(a) Quantifier-noun constructions: a number of people

(b) Measure-noun constructions: a pint of beer

(c) Container-noun constructions: a box of chocolates

(d) Part-noun constructions: a piece of cake

(e) Collection-noun constructions: a herd of elephants

In her treatment, combinations with a quantifier noun, such as number and lot, are always of type B. Apparent counterexamples, as in (17), where the assignment of a type A structure is more plausible, are accommodated by the claim that N1 is not really a quantifier noun.

(17)

(a) [The true number of vacant posts] was one thousand four hundred.

(b) … display [a variable number of entries] in a window of fixed size.

(c) He arrives in the morning with six baguettes … and [two lots of paté].

Instead, number is claimed to be a measure noun in (17a) and (17b) (Keizer Reference Keizer2007: 139), and lots is claimed to be a part noun in (17c) (p. 118). Conversely, load, which is listed as a typical measure noun (p. 113), is claimed to be quantifier noun, when the assignment of a type B structure is considered more plausible, as in (18) (p. 128).

(18) it looks as though we are going out with [a whole load of engineers]

The ambivalence also affects other types of nouns: tablespoon is listed among the container nouns (p. 114), but is claimed to be a measure noun in (19) (p. 137), and series is treated as a collection noun in the conclusion (p. 150), but is claimed to be a container noun in (20).

(19) fry the sliced leeks in [two tablespoons of olive oil]

(20) [a series of changes] occurs which are historically described as Wallerian degeneration

Besides, couple is treated as a quantifier noun (p. 112), while its near-synonym pair is claimed to be a collection noun (p. 116). With such amount of waivering, it is unclear how the lexical classification in (16) can be used as a criterion for differentiating type A from type B uses.

As an alternative, we take the position that any of the nouns in (16) can be used as the N1 in a pseudo-partitive of type A, and that many – but not all – are also used in pseudo-partitives of type B. This is in line with a common practice in studies on grammaticalization: the emergence of grammaticalized uses does not automatically lead to the extinction of the non-grammaticalized uses, but rather to their coexistence; see among others Traugott (Reference Traugott, Eckardt, Jäger and Veenstra2008). From this perspective, the relevant distinction is between nouns that are only used in type A pseudo-partitives and nouns that are also used in type B pseudo-partitives. It will be applied to a range of nouns in section 4.

3 Analysis

This section provides an analysis of the two types of pseudo-partitive that aims to meet the following two requirements. First, it should assign a more plausible structure to type B than any of the existing ones. More specifically, it should treat of as forming a constituent with N2, as argued for in Huddleston & Pullum et al. (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002), but it should also treat N2 as the head, as argued for in Akmajian & Lehrer (Reference Akmajian and Lehrer1976), Selkirk (Reference Selkirk, Akmajian, Culicover and Wasow1977), Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff1977) and many after them. Second, it should capture the intuition that type B results from a process of grammaticalization that has type A as its origin.

For this purpose we will use the framework of Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG) (Pollard & Sag Reference Pollard and Sag1994; Ginzburg & Sag Reference Ginzburg and Sag2000). This choice is motivated amongst others by the fact that the notion of head, which is of prime relevance for differentiating type A from type B, is at the center of attention in this framework, as suggested by its name. To keep the text self-contained we start with a brief introduction of the HPSG notation (section 3.1). Then we propose analyses of the pseudo-partitive, first for type A (section 3.2) and then for type B (section 3.3).

3.1 The HPSG notation

The basic notion of linguistic analysis in HPSG is that of the sign, taken in the Saussurean sense as a unit of form and meaning. Properties of signs are spelled out in terms of typed feature structures. Objects of type sign, for instance, have a form feature and a synsem feature.

(21)

(21) is a feature declaration. It consists of a type, a colon and a feature structure. Each of the features in the structure has a value that belongs to a type. In this case, the value of form is a list of graphs, such as reads, and the value of synsem is an object of type synsem, i.e. a bundle of syntactic and semantic properties, such as being a verb and denoting an action.

Signs are organized in a hierarchy of which figure 5 provides the upper layers. Subtypes inherit the properties of higher types. lexical-sign and phrase, for instance, are subtypes of sign and therefore have the features that are declared for objects of type sign, i.e. form and synsem. Besides, they may have features that are specific for the subtype and that differentiate them from other subtypes. Phrases, for instance, have a daughters feature whose value is a list of signs, but lexical signs lack this feature.

(22)

Phrases are further differentiated into those that are headed and those that are not. The former have a head-dtr feature whose value is a sign.

(23)

The PP with Georges, for instance, has two daughters (with and Georges), of which the first one is the head daughter. Non-headed phrases, such as coordinate phrases, lack the head-dtr feature. For our purpose it is the headed phrases that matter. Its subtypes will be presented in sections 3.2 and 3.3.

Figure 5. Upper layers of the hierarchy of signs

To pave the way we need more detail about the synsem values. They include amongst others the features category and content, which model the main syntactic and semantic properties of a sign respectively. The category feature has an object of type category as its value, and objects of that type are declared to have the features head, comps and marking.Footnote 1

(24)

The head value is a part of speech, such as verb or noun. These may in turn be declared to have other features. Nouns, for instance, are declared to have a case feature.

(25)

The comps value is a list of objects of type synsem. They capture the syntactic and semantic constraints which a sign requires its complements to have. Transitive verbs, for instance, have the comps value <NP>, meaning that take an NP as their complement. Signs that do not select a complement have the comps value < >, which is the empty list. The marking value differentiates signs that are fully saturated (marked) from signs that are not fully saturated (unmarked). Nominals, for instance, are marked if they contain a determiner and clauses are marked if they contain a complementizer.

The content feature has an object of type semantic-object as its value. Those objects are organized in a hierarchy, part of which is given in figure 6, quoted from Ginzburg & Sag (Reference Ginzburg and Sag2000: 386).

Figure 6. Part of the hierarchy of semantic objects

For our purpose it is the objects of type scope-object that matter, since they are the canonical type for nominals. They are declared to have the features index and restrictions.

(26)

Indices are comparable to discourse referents, but with the proviso that they contain information about person, number and gender.

(27)

Coindexed nominals, hence, share the values of these features. The restrictions value is a set of facts which jointly capture the descriptive content of the nominal. The subtypes of scope-object, i.e. quant-rel and parameter, stand for scope-objects with and without quantifier respectively.

Since all signs have a synsem feature, it follows that the category and content features are not only present in lexical signs, but also in phrases. This provides the possibility to capture correlations between the category and content values of a phrase and the category and content values of its daughters. Such correlations are expressed in terms of implicational constraints, as in (28).

(28)

What this says is that a headed phrase shares the part of speech of its head daughter.Footnote 2 A phrase that has a verb as its head daughter, for instance, is a verb phrase. If the part-of-speech is declared to have other features, their values are shared as well. Nouns, for instance, are declared to have a case feature, and share its value with the phrases which they head.

Also for the values of the content feature there are correlations between a phrase and its daughters. A nominal phrase, for instance, shares the index of its head daughter, as spelled out in (29).

(29)

Since indices are declared to have a number feature (see (27)), it is this constraint that models the propagation of the number value.

A lot more could be said about the HPSG notation, but the above suffices as a background for the analysis of the pseudo-partitive.Footnote 3

3.2 Type A

Pseudo-partitives of type A are exemplified by the bracketed strings in (2), repeated in (30).

(30)

(a) [A pound of cucumbers] yields about a pint of pickles.

(b) [Roughly five billion pounds of carpet] end up in landfills each year.

3.2.1 of as a complement-selecting head

The combination of a preposition with its nominal complement is entirely regular in type A pseudo-partitives: the preposition lexically selects a nominal complement and projects a saturated PP. The only special property concerns its semantic vacuity: in contrast to the preposition in the cat on the mat, which denotes a spatial relation between the cat and the mat, the preposition in a pound of cucumbers does not denote anything. This is clear among others from its absence in other languages. The Dutch and German equivalents of a pound of cucumbers, for instance, are respectively een pond komkommers and ein Pfund Gurken, rather than een pond van komkommers and ein Pfund von Gurken (Vos Reference Vos1999). Besides, of is not only semantically vacuous in pseudo-partitives, but also in PP complements of verbs and adjectives, as in beware of the dog and afraid of the wolf, respectively. A common property of the semantically vacuous uses is that the choice of the preposition is not free: beware and afraid require their PP complement to be introduced by of and the same holds for pound in pseudo-partitives. Employing the features that were introduced in section 3.1, the properties of the preposition that matter at this point can be spelled out as in (31).

(31)

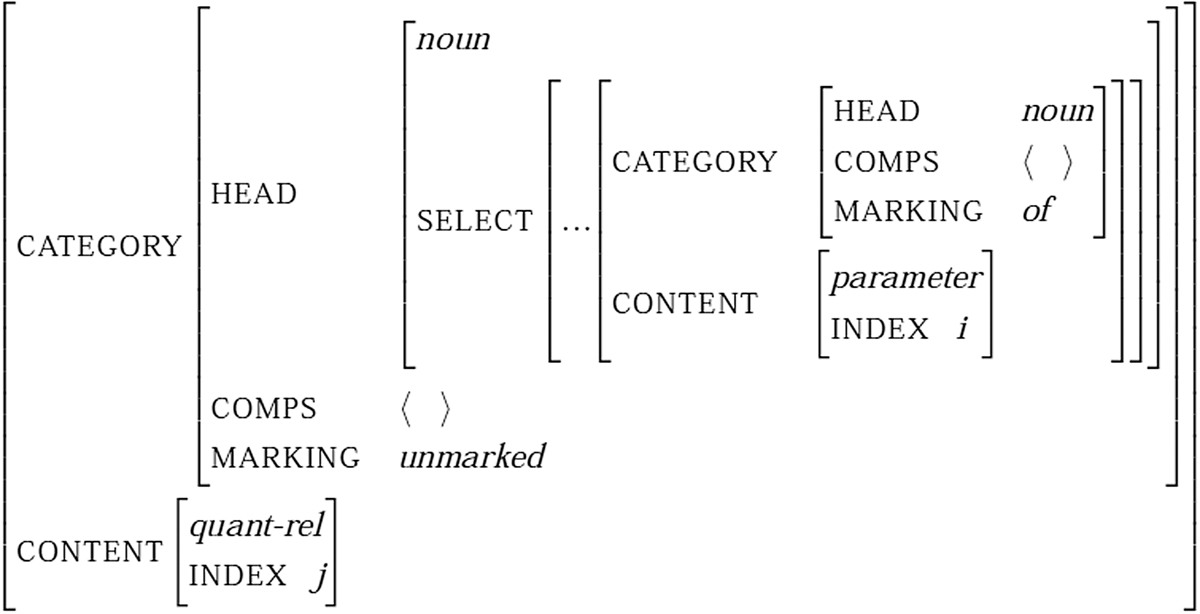

The category value contains head, comps and marking features. The value of head provides the part of speech, the value of comps spells out that it selects a nominal with an empty comps list, and the value of marking is set to of. The content value only contains the index feature, and its value is required to be identical to that of the selected nominal (![]() ). This captures the semantic vacuity.

). This captures the semantic vacuity.

To model the combination of the preposition with its complement, HPSG does not employ rewrite rules, as in PP → P NP. Instead, it employs an implicational constraint on phrases of type head-comps-phr.Footnote 4

(32)

In contrast to a rewrite rule, this constraint is cross-categorial. The head daughter can belong to any syntactic category, and so can its complement. The only requirement is that the complement matches the constraints which the head daughter has with respect to its complement. Technically, this is captured by the requirement that the synsem on the comps list of the head daughter be token-identical to the synsem value of its non-head sister (![]() ). For instance, if the head daughter requires its complement to be an accusative NP, then it is compatible with a sister that is nominal and accusative, but not with a PP or a VP. Moreover, the resulting phrase has an empty comps list, since it no longer requires a complement, after the addition of the selected complement.

). For instance, if the head daughter requires its complement to be an accusative NP, then it is compatible with a sister that is nominal and accusative, but not with a PP or a VP. Moreover, the resulting phrase has an empty comps list, since it no longer requires a complement, after the addition of the selected complement.

Application to the PP in a pound of cucumbers yields the analysis in figure 7. The preposition is the head daughter and, hence, shares its head value with the phrase (![]() ). Its comps value (

). Its comps value (![]() ) is matched with syntactic and semantic properties of its nominal complement and subtracted from the comps value of the phrase. Its marking value is also shared with the mother (

) is matched with syntactic and semantic properties of its nominal complement and subtracted from the comps value of the phrase. Its marking value is also shared with the mother (![]() ), since it must be available for checking the selection requirements of an external selector. The verb beware and the adjective afraid, for instance, select a PP that is introduced by of, rather than one that is introduced by to, in or on. The sharing is modeled by a constraint that subsumes those headed phrases in which the head daughter selects its non-head sister(s). Adopting the terminology of Sag (Reference Sag1997), we use the term head-nexus-phr for this type.

), since it must be available for checking the selection requirements of an external selector. The verb beware and the adjective afraid, for instance, select a PP that is introduced by of, rather than one that is introduced by to, in or on. The sharing is modeled by a constraint that subsumes those headed phrases in which the head daughter selects its non-head sister(s). Adopting the terminology of Sag (Reference Sag1997), we use the term head-nexus-phr for this type.

(33)

Constraint (33) is obviously similar to the Head Feature Principle, but in contrast to the HFP, which applies to all headed phrases, it only applies to phrases in which the head daughter selects the non-head daughter(s).

Figure 7. Combining the preposition with its nominal complement

Figure 7 also contains the indices. They are added as a subscript to the category value of each node. The index of the preposition is identical to that of its complement, since it is semantically vacuous, and it is also identical to that of the PP because of the Semantic Inheritance Principle.

3.2.2 N1 as a complement-selecting head

Turning now to the combination of N1 with its PP sister, we assume that the PP is a complement of the noun, rather than an adjunct. Criteria to differentiate complements from adjuncts in nominals are provided in Huddleston & Pullum et al. (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 439–43). For post-head dependents the main criterion is based on what they call ‘licensing by the head noun’: while PP adjuncts are not required to contain some specific preposition by their head sister, as shown in (34a), the choice of the preposition in the PP[of] is constrained by N1, as shown in (34b).

(34)

(a) We prefer the week before/after/around Christmas.

(b) I want a pound of/*for/*on cucumbers.

Another criterion is based on what they call ‘positional mobility’: while PP adjunts can be put in any order, as shown in (35), the PP[of] sister of N1 must precede other PP dependents, as shown in (36).

(35)

(a) that cat of the neighbors with the long tail

(b) that cat with the long tail of the neighbors

(36)

(a) two pounds of cucumbers in one bag

(b) *two pounds in one bag of cucumbers

Not mentioned in Huddleston & Pullum et al. (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 439–43), but equally telling, is the test of iteration. While PP adjuncts can be iterated, as in (37a), the PP sister of N1 cannot be iterated, as shown in (37b).

(37)

(a) They were dancing in the rain in Paris in the summer of 1987.

(b) I want a pound of cucumbers (*of tomatoes).

In short, there is sufficient evidence for the assumption that N1 takes its PP[of] sister as a complement. Technically, this is captured by the feature structure in (38).

(38)

The category value is similar to that of the preposition in (31). We are dealing with a noun that selects a complement that is required to take the form of a PP[of], and that is unmarked, i.e. determinerless. The content value, though, is rather different from that in (31), since the noun is not semantically vacuous. Instead, it denotes a unit (j) that is used for measuring whatever its PP complement denotes (i). Given that indices contain a number feature, the assignment of different indices to N1 and its complement implies that the number value of N1 may differ from that of its complement. That is necessary to license the combinations in (30), where the number values of N1 and the NP in its complement are different (pound of cucumbers and pounds of carpet).

When applied to a specific noun and PP complement, the resulting structure is as shown in figure 8. N1 shares its head value (![]() ), its marking value (

), its marking value (![]() ) and its index (j) with the phrase. Its comps value, by contrast, is matched with its PP sister (

) and its index (j) with the phrase. Its comps value, by contrast, is matched with its PP sister (![]() ) and subtracted from the comps list. The constraint that models this is exactly the same as the one that we used to model the combination of the preposition and its nominal complement in section 3.2.1, see (32).

) and subtracted from the comps list. The constraint that models this is exactly the same as the one that we used to model the combination of the preposition and its nominal complement in section 3.2.1, see (32).

Figure 8. Combining N1 with its PP complement

3.2.3 The determiner as a head-selecting functor

Having modeled the combinations of N1 with its PP complement and of the preposition with its nominal complement, we now turn to the combination of the determiner and its nominal sister. This combination is subject to constraints. The article in a pound of cucumbers, for instance, requires its sister to be nominal, singular and unmarked. This must be included in the lexical entry of the article in order to block the combination with verbs (*a have), plural nouns (*a pounds) and fully saturated NPs (*a the carpet). It is in principle possible to include this in the comps value of article, but the consequence of this option is that the head of a pound is the article, rather than the noun. There are frameworks that welcome this consequence, such as the post-gb variants of Transformational Grammar, but HPSG adopts the more familiar assumption that the noun is the head in its combination with the article, following common practice in theory-neutral approaches (Van Eynde Reference Van Eynde2021). This implies that the non-head daughter, i.e. the article, needs the means to select and constrain its head sister. To model this, HPSG uses the select feature. It is declared for objects of type part of-speech and is, hence, part of the head value (Allegranza Reference Allegranza, Balari and Dini1998; Van Eynde Reference Van Eynde, Coppen, Halteren and Teunissen1998).Footnote 5

(39)

Employing this feature, the category value of the article is shown in (40).

(40)

The article selects an unmarked nominal as its head sister and requires its number value to be singular. Its comps value is the empty list and its marking value is set to a, which is a subtype of marked.Footnote 6

In much the same way as the comps requirements of the head daughter must match the synsem values of its non-head sister(s), the select requirements of a non-head daughter must match the synsem value of its head sister. This is modeled in a general constraint on phrases of type head-functor.

(41)

In the hierarchy of signs in figure 5, head-functor-phr is a subtype of head-adjunct-phr.Footnote 7 Typical of the latter is that the phrase shares its marking value with the non-head daughter, as spelled out in (42).

(42)

The combination of the article and its nominal sister is modeled in figure 9. The select value of the article matches the synsem value of its nominal sister (![]() ) and shares its marking value with the resulting NP (

) and shares its marking value with the resulting NP (![]() ), while the nominal head daughter shares its head value (

), while the nominal head daughter shares its head value (![]() ) and its index with the phrase, as required by the Head Feature Principle and the Semantic Inheritance Principle.

) and its index with the phrase, as required by the Head Feature Principle and the Semantic Inheritance Principle.

Figure 9. Combining the article with its nominal head sister

3.2.4 Summing up

Pseudo-partitives of type A can be modeled in terms of the right-branching structure that was already given in figure 1. This section has added more detail, making use of the phrase type hierarchy of HPSG. More specifically, the combination of the preposition with its nominal sister has been shown to be an instance of head-comps-phr (section 3.2.1), and the same has been argued for the combination of N1 with its PP sister (section 3.2.2), but the combination of the resulting nominal with the article has been argued to be an instance of another type of phrase, i.e. head-functor-phr (section 3.2.3).

3.3 Type B

Pseudo-partitives of type B are exemplified by the bracketed strings in (3), repeated in (43).

(43)

(a) [A lot of things] happen and change over the years.

(b) [Lots of power] is necessary to churn heavy soil.

For the analysis we adopt the structure spelled out in figure 10.

Figure 10. Internal structure of type B pseudo-partitives

This differs from the structures in figure 2 and figure 3, proposed in Akmajian & Lehrer (Reference Akmajian and Lehrer1976) and Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff1977) respectively, in that the preposition is neither part of a complex determiner nor a syncategorematic linker, but rather a part of the N2 projection, as advocated in Huddleston & Pullum et al. (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002). At the same time, figure 10 also differs from the analysis in figure 4, proposed in Huddleston & Pullum et al. (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002), in that the preposition is not the head of a PP, but a functor that is adjoined to N2. In fact, N2 is not only the head in its combination with the preposition, but also in its combination with N1. This straightforwardly accounts for the fact that the phrase shares its number value with N2.

As compared to the analysis of type A in section 3.2, the intuition that type B is its grammaticalized variant, as argued in Traugott (Reference Traugott, Eckardt, Jäger and Veenstra2008), is made explicit by the syntactic role of the preposition and of N1: while they have their usual head-of-PP and head-of-NP status in type A, they have functor status in type B. To model this we do not need to resort to any ad hoc devices. All we need is the phrase types, feature declarations and constraints that have already been introduced in sections 3.1 and 3.2. To demonstrate this we proceed in the same bottom-up manner as in the previous section, subsequently treating the combination of the preposition with N2 (section 3.3.1), the combination of N1 with its nominal sister (section 3.3.2) and the addition of the determiner (section 3.3.3).

3.3.1 of as a head-selecting functor

What differentiates the complement-selecting use of of in type A from its head-selecting use in type B is easy to glean from the rewrite rules in (44).

(44)

(a) PP[of ] → P[of ] NP

(b) NP[of ] → P[of ] NP

In the former, the preposition is the head of a PP; in the latter, it is adjoined to an NP. A criterion to differentiate them is the strandability test. Given that complements can be extracted, while heads cannot, it follows that strandable prepositions such as those in (45) are heads of PPs.

(45)

(a) What are you [afraid of __] ?

(b) This is something we definitely want [a piece of __].

By contrast, prepositions that are adjoined to an NP, cannot be stranded. This is the case for a number of uses of of that do not fit the (44a) mold. One is discussed and analyzed in Maekawa (Reference Maekawa and Müller2015: 146). It concerns the use of the preposition in these kind/sort/type of problems, as used in (46). Others are treated in Van Eynde (Reference Van Eynde2018). They concern the use of of in the Binominal Noun Phrase Construction, as in (47), and in the of variant of the Big Mess Construction, as in (48) (Kim & Sells Reference Kim and Sells2011; Van Eynde Reference Van Eynde2018).

(46) [These sort of problems] are very hard to solve.

(47) She divorced [her nitwit of a husband] last year.

(48) It was [so big of a mess] in there that we lost track.

In these uses the preposition cannot be stranded, as shown in (49).

(49)

(a) *What does he like [these sort of __] ?

(b) *This is her husband whom [a nitwit of __] she divorced last year.

(c) *What was it [so big of __] in there that you lost track?

The same holds for the preposition in type B pseudo-partitives, as demonstrated by Huddleston & Pullum et al.'s (8)–(9), repeated in (50).

(50)

(a) *Most students like continuous assessment but [a lot of __] prefer the old examination system.

(b) *We called a meeting of the first-year students, whom [a lot of __] had complained about the assessment system.

There is, hence, independent evidence for the assignment of functor status to the use of of in type B pseudo-partitives. Its properties are modeled in (51).

(51)

As compared to the head-of-PP use, spelled out in (31), there are many similarities, including the part of speech, the semantic vacuity, the marking value and the selection of a nominal sister. What differs, though, is the mode of selection. The nominal is not selected as a complement, but as a head, more specifically by the select value. Besides, there are more specific constraints on the marking and content values of the selected nominal. While the complement-selecting of does not impose any constraints on the marking value of its NP sister, the head-selecting of requires it to be bare, which is a subtype of unmarked. Similarly, while the complement-selecting of is compatible with both quantified and non-quantified nominals, the head-selecting of only combines with the latter, i.e. those of type parameter.Footnote 8 When combined with a specific nominal, the resulting analysis is as shown in figure 11. The select value of the preposition (![]() ) matches the synsem value of the nominal and its marking value (

) matches the synsem value of the nominal and its marking value (![]() ) is shared with the phrase, while the head daughter (N2) shares its head value (

) is shared with the phrase, while the head daughter (N2) shares its head value (![]() ) and its index (i) with the phrase.Footnote 9 Given that the index includes the number value, the net result is that of power is a singular nominal.

) and its index (i) with the phrase.Footnote 9 Given that the index includes the number value, the net result is that of power is a singular nominal.

Figure 11. Combining a prepositional functor with its head sister

Summing up, to pave the way for an analysis in which N2 is the head in type B pseudo-partitives it is not necessary to resort to a poorly motivated treatment of the preposition, as in Akmajian & Lehrer (Reference Akmajian and Lehrer1976), Selkirk (Reference Selkirk, Akmajian, Culicover and Wasow1977), Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff1977), Keizer (Reference Keizer2007) and Traugott (Reference Traugott, Eckardt, Jäger and Veenstra2008). Instead, it is possible to adopt the usual tree geometry and to get the desired outcome if one adopts the independently motivated assumption that there are prepositions which – in some of their uses – are head-selecting functors, rather than complement-selecting heads.Footnote 10

3.3.2 N1 as a head-selecting functor

Given the functor status of the preposition in type B pseudo-partitives, it follows that a phrase like lots of power is not an [N + PP] sequence, but a juxtaposition of two nominals. In such a combination, it is quite common for the rightmost nominal to be the head. In John's sisters, for instance, sisters is the most plausible candidate for head status, since it shares its case and number values with the phrase, while the other nominal is a functor, comparable to a possessive determiner, such as his or our. The same holds for combinations of a numeral and a noun. In a thousand trees and one hundred houses, for instance, the plural nouns are the most plausible candidates for head status, since they share their number value with the phrase, while the numerals are singular nouns with functor status. An HPSG analysis is provided in Maekawa (Reference Maekawa, Doug, Butt, Crysmann, King and Müller2016: 431–2). It builds on the functor analysis of the Dutch numerals in Van Eynde (Reference Van Eynde2006).

Taking a cue from these analyses, we assume that the combination of the two nominals in a type B pseudo-partitive is right-headed too and that N1 is a head-selecting functor, as spelled out in (52).

(52)

There is a lot that (52) has in common with its N1 counterpart in type A pseudo-partitives, such as its part of speech, its marking value and its selection of an XP[of] sister. What differs is the mode of selection (by select instead of comps) and the category of the selected sister (NP instead of PP). This syntactic difference is mirrored by a semantic one: while the N1 in a type A pseudo-partitive denotes an object of type parameter, the N1 in a type B pseudo-partitive denotes an object of type quant-rel. When combined with a specific nominal, the resulting analysis is as shown in figure 12. The phrase shares its head value (![]() ) and its index (i) with the rightmost nominal, and its marking value (

) and its index (i) with the rightmost nominal, and its marking value (![]() ) with the functor daughter. The latter's select value matches the synsem value of its head sister (

) with the functor daughter. The latter's select value matches the synsem value of its head sister (![]() ). Since the number value is part of the index, which is shared with the head daughter, lots of power is treated as singular, as it should be.

). Since the number value is part of the index, which is shared with the head daughter, lots of power is treated as singular, as it should be.

Figure 12. Combining N1 with its head sister

A welcome consequence of this analysis is that it accounts for the contrast between (5) and (6), repeated in (53)–(54).

(53)

(a) A review of a new book about French cooking came out yesterday.

(b) A review came out yesterday of a new book about French cooking.

(54)

(a) A number of stories about Watergate soon appeared.

(b) *A number soon appeared of stories about Watergate.

The PP[of] sister of review in (53) can be extraposed, as is normal for PP dependents, but the sister of number in (54) cannot, since it is a nominal head rather than a PP dependent. The ill-formedness of (54b), hence, follows from the general constraint that heads cannot be extraposed.

Summing up, the functor treatment of N1 in type B pseudo-partitives yields the result we need without tinkering with the tree geometry, and receives support from the existence of other constructions in which a noun is used as a functor. As in the case of the preposition, it is worth stressing that the functor treatment is limited to specific uses. In the same way as of is used both as a complement-selecting head and as a head-selecting functor, quantifier nouns, such as lot(s) and number, are not only used as head-selecting functors in type B pseudo-partitives, but also as complement-selecting heads in type A pseudo-partitives, as illustrated in (17), repeated in (55).

(55)

(a) [The true number of vacant posts] was one thousand four hundred.

(b) … display [a variable number of entries] in a window of fixed size.

(c) He arrives in the morning with six baguettes … and [two lots of paté].

The difference between nominal head and nominal functor uses will be explored in more detail in section 4.

3.3.3 Adding the determiner

The indefinite article in a lot of things must be part of the phrase that is headed by the singular N1 lot, since it is not compatible with the plural N2. This is reflected by the left-branching structure in figure 13.Footnote 11

Figure 13. Type B pseudo-partitive with phrasal N1

The quantifying phrase a lot shares its head value (![]() ) and its index (j) with lot, and its marking value (

) and its index (j) with lot, and its marking value (![]() ) with the article.Footnote 12 The latter's select value matches the synsem value of lot (

) with the article.Footnote 12 The latter's select value matches the synsem value of lot (![]() ). The top node in figure 13 shares its head value (

). The top node in figure 13 shares its head value (![]() ) and its index (i) with the rightmost nominal, and its marking value (

) and its index (i) with the rightmost nominal, and its marking value (![]() ) with the quantifier a lot. The latter's select value matches the synsem value of of things (

) with the quantifier a lot. The latter's select value matches the synsem value of of things (![]() ). This select value is, furthermore, shared with lot since it is part of its head value (

). This select value is, furthermore, shared with lot since it is part of its head value (![]() ). Since the number feature is part of the index, the resulting NP is plural, just like things. There is, hence, no need for a device that has ‘the grammatical number percolating upwards from the oblique’ (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 352), since (of) things is the head. Besides, this analysis also avoids another problem with the Huddleston & Pullum et al. approach, namely that the indefinite article is combined with a plural nominal in figure 4. This is not the case in figure 13, where the article combines with lot rather than with lot of things.

). Since the number feature is part of the index, the resulting NP is plural, just like things. There is, hence, no need for a device that has ‘the grammatical number percolating upwards from the oblique’ (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 352), since (of) things is the head. Besides, this analysis also avoids another problem with the Huddleston & Pullum et al. approach, namely that the indefinite article is combined with a plural nominal in figure 4. This is not the case in figure 13, where the article combines with lot rather than with lot of things.

3.3.4 Summing up

In pseudo-partitives of type B the preposition is a head-selecting functor rather than a complement-selecting head (section 3.3.1) and the same holds for N1 (section 3.3.2). The determiner, if there is one, is added to N1 (section 3.3.3). The net result is that pseudo-partitives of type B share the index and, hence, the number value of N2.

3.4 Summary

This section has provided an analysis of both types of pseudo-partitives. It is based on the assumption that type B is the grammaticalized counterpart of type A, as pointed out in Traugott (Reference Traugott, Eckardt, Jäger and Veenstra2008). Differently from the existing treatments of type B, which are at odds either with standard constituency tests or with general patterns of feature propagation, this treatment is based on assumptions that are independently motivated, in the sense that there are other prepositions and common nouns for which a functor treatment is more plausible than a head treatment.

4 Head or functor?

In the previous section we have used combinations with a measure noun (pound) to exemplify the properties of type A and combinations with a quantifier noun (lot) to exemplify the properties of type B. We have also signaled, though, that pseudo-partitives with a quantifier noun are not always of type B, as shown in (55). Rather than a problem, this is a confirmation of the assumption that type B is a grammaticalized counterpart of type A, since the existence of grammaticalized uses does not necessarily lead to the extinction of the original non-grammaticalized uses. In conformity with that assumption we make a distinction between nouns that occur in both types of pseudo-partitives (section 4.1) and nouns that only occur in type A pseudo-partitives (section 4.2). Much of the discussion will be devoted to the issue of how the type B uses can be differentiated from the type A uses.

For the purpose of concreteness the discussion is larded with examples and quantitative data from the 450-million-word Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA; Davies Reference Davies2008–). It consists of fragments from eight different genres, i.e. fiction (FIC), popular magazines (MAG), newspapers (NEWS), academic texts (ACAD), spoken language (SPOK), TV and movies (TV/MOV), blogs (BLOG), and web pages (WEB).

4.1 Quantifier and collection nouns

Starting with the quantifier nouns, their use as N1 in pseudo-partitives is canonically of type B, as in (56), where the verbs all share the number value of N2.

(56)

(a) A lot of thingspl happenpl and changepl over the years. (COCA 2017 NEWS)

(b) Lots of powersg issg necessary to churn heavy soil. (COCA 2007 MAG)

(c) A number of studiespl indicatepl that evaluation is an important part of metacognitive control. (COCA 1997 ACAD)

(d) A multitude of challengespl facepl the food-service industry. (COCA 1996 MAG)

(e) Plenty of ticketspl remainpl for Saturday's game. (COCA 1997 NEWS)

Occasionally, though, the combinations are of type A, as in (57), where the verbs share the number value of N1.

(57)

(a) The numbersg of new students continuessg to grow. (COCA 2003 NEWS)

(b) A multitudesg of bowls turnssg bookshelves into functional display cabinet. (COCA 2009 MAG)

The contrast correlates with a difference in semantic interpretation: While the VPs in (56) express a property that is attributed to N2, the VPs in (57) express a property that is attributed to N1. The use of the singular verb in (57a), for instance, is due to the fact that it is the number that is claimed to grow rather than the students. Similarly, the use of a singular verb in (57b) conveys the information that it is not so much the bowls in themselves but rather their high number that has the effect of turning the bookshelves into a display cabinet.

To differentiate the type A from the type B uses the agreement test provides a useful criterion, but since it is only applicable to pseudo-partitives in subject position, it has its limitations. To overcome these we propose – generalizing from examples like those in (56) and (57) – four criteria that are also applicable to pseudo-partitives in other positions than the subject one.

First, while type A pseudo-partitives can be introduced by any kind of determiner, type B pseudo-partitives are either bare (plenty, lots) or introduced by the indefinite article (a lot, a number, a multitude).

Second, in type A pseudo-partitives the noun can be combined with a numeral, as in (58), where lots has the usual more-than-one interpretation.

(58) Just because [two lots of physicians] have decided not to merge does not mean our own course should falter. (COCA 2014 ACAD)

This addition is not licensed in type B pseudo-partitives, as in (56b).

Third, in type A pseudo-partitives the noun can be preceded by any adjective that is semantically compatible with it and the resulting combination has a compositional meaning. In the high number of new students and a variable number of entries the adjectives high and variable modify the noun number and contrast with their respective antonyms low and fixed in the usual way. In type B pseudo-partitives the choice is limited to a small subset of the adjectives. For a … lot of, for instance, the query in (59) yields 8,783 hits in COCA, of which 5,283 (60.15%) concern whole and 3,256 (37.07%) awful.

(59) a|an j* lot of

Moreover, the combination is not compositional. whole and awful have an intensifying function in this combination, rather than a descriptive one, and do not contrast with their antonyms partial and gentle. The fixed-phrase status of these combinations is especially clear in the case of deal, which can only be the N1 of a type B pseudo-partitive when it is combined with either great or good.

(60) A great deal of peoplepl likepl to search feral swine. (COCA 2012 BLOG)

When great is omitted, the combination no longer qualifies as a pseudo-partitive. In (61), for instance, deal denotes a transaction rather than a quantity.

(61) Dealspl of this size also receivepl regulatory review. (COCA 2018 NEWS)

The same holds for load, which requires the presence of whole in type B pseudo-partitives, as in (62). If the adjective is omitted, as in (63), it denotes a delivery rather than a quantity.

(62) There is a whole load of stuff in the literature on bow shock. (COCA 2018 MAG)

(63) You want a load of bricks to arrive when it is ordered. (COCA 2015MAG)

Fourth, in type A pseudo-partitives the noun can take a plural affix and the resulting form has the usual more-than-one interpretation. The N1 in the rising numbers of foreign students, for instance, denotes more than one number, in the same way as the first noun in the tables in the corner denotes more than one table. By contrast, in type B pseudo-partitives the noun either lacks a plural counterpart, as in the case of plenty, or if it has one, it does not have the usual more-than-one interpretation. In (56b), for instance, lots does not denote more than one lot, but rather a large quantity. It is in fact semantically equivalent to the singular a lot.

(64) sums up the characteristic properties of type B pseudo-partitives.

(64) Properties of the type B use:

1. restrictions on the determiner (bare or indefinite article)

2. incompatibility with numerals

3. restrictions on the combination with adjectives (fixed phrase rather than compositional)

4. neutralization of the number distinction

To model these properties we do not need to add much to what is already given in section 3. Property 1, for instance, is related to the difference in semantic type of N1: while the complement-selecting heads that form the core of a type A pseudo-partitive have a content value of type parameter, as spelled out in (38) in section 3.2.2, the head-selecting functors in a type B pseudo-partitive have a value of type quant-rel, as spelled out in (52) in section 3.3.2. As a consequence, given that most determiners select a nominal that denotes an object of type parameter, they are compatible with the former, but not with the latter. The exception is the indefinite article, which does not require the selected nominal to be of a specific semantic type and which is, hence, compatible with both. The semantic type of N1 also accounts for Property 2. Given that numerals select a nominal that is not yet quantified, they are compatible with nouns that have a content value of type parameter, but not with nouns that have a content value of type quant-rel. Property 3 is due to lexicalization. The non-compositional nature of the combination with adjectives in type B is best handled by treating them as separate lexical units. This is especially clear for great deal, good deal and whole load, since they cannot be used as the N1 in a type B pseudo-partitive, if the adjective is omitted. Property 4 is also due to lexicalization. The neutralization of the number distinction for lot(s) can be handled by treating lot and lots as separate lexical units, rather than as the singular and plural forms of the same lexeme.

Taken together, the conditions on N1 in type B are quite restrictive, but when they are met, the pseudo-partitive is more likely to be of type B than of type A. This is confirmed by quantitative data from COCA. Using the search strings in (65), we can check for pseudo-partitive subjects whether the verb shares the number value of N1 or N2.

(65)

(a) n-sg of n-pl verb-3sg or verb-base

(b) n-pl of n-sg verb-3sg or verb-base

(65a) retrieves pseudo-partitives with a singular N1 that immediately precede a verb that is tagged as 3sg, c.q. base.Footnote 13 (65b) does the same for pseudo-partitives with a plural N1. The results are summarized in table 1. They clearly show that the type B use is much more common than the type A use.

Table 1. Pseudo-partitives with a quantifier noun as N1

Moreover, several of the combinations in the left column do not qualify as instances of type A. Some are simply ill-formed, such as (66), which should have a plural verb, and (67), which should have a plural N2.

(66) Plenty of guys has them. (COCA 1997 FIC)

(67) Lots of language use the JVM besides Java. (COCA 2012 BLOG)

Others are well-formed, but do not qualify as type A. An example is (68).

(68) A lot of melanocytes meanssg a brown eye. (COCA 2012 BLOG)

This superficially looks like an instance of agreement with N1, but a closer look reveals that something else is at work here, since the verb is also singular when both N1 and N2 are plural, as in (69).

(69)

(a) Lots of dragonflies meanssg it's gonna rain soon. (COCA 2003 MOV)

(b) Lots of vegetables issg key. (COCA 2015 MAG)

This suggests that the use of a singular verb in (68) and (69) is not due to the fact that the pseudo-partitive subjects are of type A, but rather to a number mismatch between subject and verb, comparable to what we see in (70).

(70)

(a) Eggs is my favorite breakfast.

(b) Eggs bothers me more than okra.

In their treatment of these ‘singular plurals’ Pollard & Sag (Reference Pollard and Sag1994: 86–8) argue that they involve ‘reference transfer’, converting an NP with a plural index into an NP with a singular index. By the same token, we assume that the pseudo-partitive in (68) has a plural index, just like those in (69). It is, hence, of type B, and its combination with a singular verb is due to reference transfer.

Setting aside the ill-formed combinations and the instances of reference transfer, we are left with a very small number of genuine type A uses. One of them is (57b). Another one is (71).

(71) A lotsg of studies statessg that creativity can be achieved with just few moments of fun. (COCA 2012 BLOG)

In sum, pseudo-partitives which have a quantifier noun as N1 that shows the four properties spelled out in (64) are nearly all of type B. In other words, quantifier nouns show a very high degree of grammaticalization when they are used in pseudo-partitives.

Turning now to the collection nouns, we observe the same coexistence of type A and type B uses. In type A, they may combine with any determiner, numeral or semantically compatible adjective, and have a plural counterpart with the canonical more-than-one interpretation. Moreover, if the pseudo-partitive is in subject position, the verb shows agreement with N1, as in (72).

(72)

(a) A groupsg of police cruisers issg speeding across the bridge with light and sirens. (COCA 2004 FIC)

(b) A groupsg of men issg using green garbage cans. (COCA 1995 NEWS)

There are also instances, though, which show the agreement pattern that is characteristic of type B, as in (73).

(73)

(a) A group of immigrantspl movepl in and, seemingly, overnight, they're far more successful than native residents. (COCA 1990 SPOK)

(b) A group of menpl sitpl on the sofas. (COCA 1996 FIC)

In this use, the collection noun does not combine with numerals. Replacing the article with the numeral one, for instance, yields a well-formed combination in (72), but not in (73). Equally telling is the fact that the plural groups is only used in type A pseudo-partitives.

Table 2 provides some quantitative data from COCA. They show that, as far as agreement is concerned, the pseudo-partitives with a singular collection noun are divided in roughly equal numbers over type A and type B, while pseudo-partitives with a plural collection noun are of type A. This shows that the collection nouns demonstrate a significantly lower degree of grammaticalization than the quantifier nouns.

Table 2. Pseudo-partitives with a collection noun as N1

4.2 Measure and container nouns

Measure nouns denote units of weight (pound, kilo, ton, …), length (foot, inch, meter, …), content (liter, gallon, …), etc. When used in a pseudo-partitive, they do not show any of the characteristics of functor status: they are not restricted to being bare or indefinite; they routinely combine with numerals, as in five liters of milk; they combine with any adjective that is semantically compatible with a measure noun; and they show the usual number distinction: liters of milk denotes more than one liter of milk and is, hence, semantically different from a liter of milk. Moreover, when used in subject position, the verb shares the number value of N1, as illustrated in (74) and (75).

(74) A poundsg of cucumbers yieldssg about a pint of pickles. (COCA 2011 MAG)

(75) About two poundspl of plutonium givepl off energy equal to 30 million … (COCA 1999 ACAD)

As is clear from the figures in table 3, there are some exceptions for combinations with a plural N1. Some are listed in (76).

(76)

(a) 1.5 million pounds of beef hassg been recalled. (COCA 2012 BLOG)

(b) Roughly ten inches of snow issg expected to pile up across the Chicago area. (COCA 2018 NEWS)

(c) And today as much as six inches of snow issg expected in the Upper Midwest. (COCA 2013 SPOK)

(d) 1 to 2 feet of snow issg expected over the Cascades. (COCA 2012 WEB)

Since N2 is singular in these examples, they look like instances of type B, but the fact that they all include a numeral suggests otherwise. More plausible is the assumption that we are dealing with a number mismatch between subject and verb, comparable to what we see in (77).

(77) Five pounds is a lot of money.

Confirming evidence is provided by the existence of combinations in which both N1 and N2 are plural and in which the verb is singular nonetheless, as in (78).

(78) 11/2 pounds of beans makes 6 to 8 servings. (COCA 2012 WEB)

This is comparable to the combinations with lots in (69).

Table 3. Pseudo-partitives with a measure noun as N1

The same observations can be made about pseudo-partitives with a container noun. The noun itself does not show any of the four functor properties and when the pseudo-partitive is in subject position, the verb shares the number value of N1.

(79)

(a) A boxsg of chocolates issg full of surprises. (COCA 1996 MAG)

(b) A cupsg of lentils containssg 25 percent of the RDA of iron for a woman. (COCA 1993 MAG)

(80)

(a) Plastic bottlespl of paint sitpl in the alley. (COCA 1997 FIC)

(b) Eight cupspl of tea givepl you the same amount of caffeine as three cups of coffee. (COCA 1999 MAG)

In sum, pseudo-partitives with a measure or container noun as N1 are invariably of type A. These nouns are complement-selecting heads and lack the grammaticalized functor uses.

4.3 Summing up

To differentiate pseudo-partitives of type B from those of type A we have used four criteria, i.e. the restriction to a small subset of determiners, the incompatibility with numerals, the non-compositional nature of the combination with adjectives and the neutralization of the number distinction. Together with the agreement test, they provide evidence that pseudo-partitives with a measure or container noun are invariably of type A, while those with a quantifier or collection noun have both type A and type B uses. The current coexistence of grammaticalized functor uses and non-grammaticalized head uses for these nouns is a normal consequence of the fact that grammaticalization is a gradual process. For a lot this process is described in some detail in Traugott (Reference Traugott, Eckardt, Jäger and Veenstra2008), who locates the emergence of the grammaticalized (type B) use around the nineteenth century.

5 Pseudo-partitives without a preposition

Since the preposition that links N1 to N2 is semantically vacuous, it can be omitted without loss of information. This accounts for its absence in Dutch pseudo-partitives, not only when N1 is a measure noun, as already shown in section 3.2.1, but also when it is a quantifier noun, as in een aantal studenten ‘a number of students’, a collection noun, as in een groep toeristen ‘a group of tourists’, or a container noun, as in een fles wijn ‘a bottle of wine’. Pseudo-partitives without a preposition also exist in English, albeit on a more limited scale. For the discussion we distinguish between two types.

The first concerns combinations in which N1 is a quantifier noun, as in (81)–(82).Footnote 14

(81) A few handspl gopl up when he asks if there are valid excuses. (COCA 1995 FIC)

(82) A great many thingspl dependpl on that outcome. (COCA 2012 FIC)

In these combinations few and many show the typical characteristics of a head-selecting functor. They only combine with the indefinite article; they are not compatible with numerals; the combinations with an adjective are not compositional – with many sharing the property of deal that it requires the presence of either great or good; and they lack a plural counterpart (*fews, manies). Moreover, if the pseudo-partitive is in subject position, the verb shares the number value of N2, as shown in (81)–(82). Exceptions are even less common than for the quantifier nouns that were discussed in section 4.1. COCA, for instance, contains 341 instances of [a few Npl] and 102 of [a good/great many Npl] in subject position, of which none is combined with a singular verb. Pseudo-partitives with few and many are, hence, invariably of type B, and the lexical entries of few and many are of the same kind as that of lot; see (52) in section 3.3.2. The only difference is that they select a bare nominal, instead of one that is introduced by of.

The second type of pseudo-partitives without a preposition concerns combinations in which N1 belongs to a subclass of the numeral nouns, comprising dozen, hundred, thousand and billion. Examples from COCA are given in (83).

(83)

(a) A dozen eggspl costpl just over $ 5 US (COCA 2012 BLOG)

(b) A hundred kidspl playpl at the academy (COCA 2012 NEWS)

(c) A billion beespl swarmpl the Empire State Building (COCA 2012 WEB)

In contrast to the quantifier nouns (few, many), they are also used with a preposition, as in (84).

(84)

(a) A dozensg of eggs issg approximately 1.5 pounds. (COCA 2010WEB)

(b) Dozenspl of vendors droppl off and pickpl up merchandise. (COCA 2008 NEWS)

If used in the plural, the presence of the preposition is even obligatory: dozens *(of) eggs, hundreds *(of) kids, billions *(of) bees.

Comparing the examples in (83) and (84) the agreement facts suggest that the former are of type B, with the verb sharing the number value of N2, while the latter are of type A, with the verb sharing the number value of N1. This is confirmed by other properties of N1. First, the indefinite article can be replaced by another determiner, such as the demonstrative this, in (84a), but not in (83a). Second, the indefinite article can be replaced by the numeral one in (84a), but not in (83a). Third, N1 has a plural counterpart with the usual more-than-one interpretation in (84), but not in (83). Apparently, numeral nouns of type dozen, hundred, thousand, … behave as complement-selecting heads when the preposition is present, and as head-selecting functors when the preposition is omitted.

This brief discussion of pseudo-partitives without a preposition, hence, reveals yet another difference between the head and functor uses of N1. If N1 is a complement-taking head, the preposition cannot be omitted, but if it is a head-selecting functor, omission is possible for subclasses of N1. The non-omissibility of the preposition in type A pseudo-partitives is in turn related to the fact that English nouns can take PP complements, but not NP complements.Footnote 15

6 Conclusion

English pseudo-partitives are [N1 – of – N2[bare]] sequences. They come in two types, depending on whether they share the number value of N1 (type A) or that of N2 (type B). Type A can be analyzed along familiar lines, with N1 taking a PP[of] complement, but type B is a harder nut to crack. Existing analyses resort to unorthodox treatments of the preposition (Akmajian & Lehrer Reference Akmajian and Lehrer1976; Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1977; Selkirk Reference Selkirk, Akmajian, Culicover and Wasow1977; Keizer Reference Keizer2007) or unheard-of percolation mechanisms (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002). Employing the framework of Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar we have developed an analysis of both types of pseudo-partitives in which the differences between them are shown to result from the different status of N1: while it is a complement-selecting head in type A, it is a head-selecting functor in type B. The shift from head to functor status is an instance of grammaticalization and has been shown to apply in various degrees to different classes of N1. Making use of COCA, we have shown that it mainly affects the quantifier nouns and to a lesser extent the collection nouns, while the measure and container nouns are not affected. The shift from head to functor status of N1 is mirrored by that of the preposition: while the preposition is the complement-selecting head of a PP in type A, it is a head-selecting functor in type B. In a last step, we have extended the analysis to pseudo-partitives without of.

Speaking in more general terms, the analysis of the English pseudo-partitive in this article has demonstrated how insights about the process of grammaticalization can be integrated into a framework for formal analysis. More specifically, the coexistence of head and functor uses for certain nouns and prepositions, which is synchronically motivated, mirrors the coexistence of grammaticalized and non-grammaticalized uses, which results from diachronic processes. From this perspective, the article shows how formal and functional approaches can be combined to shed light on issues where synchronic and diachronic considerations intertwine.